new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: enchanted forests, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 20 of 20

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: enchanted forests in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Lauri Lu,

on 9/10/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

H.D.,

hilda doolittle,

imagism,

lara vetter,

modernist writer,

Moravianism,

richard aldington,

Sea Garden,

travelogues,

Literature,

sexuality,

World Travel,

modernism,

ezra pound,

OBO,

*Featured,

Online products,

Oxford Bibliographies,

Arts & Humanities,

Add a tag

American-born, British citizen by an ill-fated marriage, the modernist writer Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) was wary of nationalism, which she viewed as leading inevitably to either war or imperialism. Admittedly, she felt—as she wrote of one of her characters—“torn between anglo-philia and anglo-phobia,” and like all prominent modernists of her day, her views were probably not as enlightened as ours.

The post Remembering H.D. on her 130th birth anniversary appeared first on OUPblog.

Eric Bennett has an MFA from

Iowa, the MFA of MFAs. (He also has a Ph.D. in Lit from Harvard, so he is a man of fine and rare academic pedigree.) Bennett's recent book

Workshops of Empire: Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing during the Cold War is largely about the Writers' Workshop at Iowa from roughly 1945 to the early 1980s or so. It melds, often explicitly,

The Cultural Cold War with

The Program Era, adding some archival research as well as Bennett's own feeling that the work of politically committed writers such as Dreiser, Dos Passos, and Steinbeck was marginalized and forgotten by the writing workshop hegemony in favor of individualistic, apolitical writing.

I don't share Bennett's apparent taste in fiction (he seems to consider Dreiser, Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Thomas Wolfe, etc. great writers; I don't), but I sympathize with his sense of some writing workshops' powerful, narrowing effect on American fiction and publishing for at least a few decades. He notes in his conclusion that the hegemonic effect of Iowa and other prominent programs seems to have declined over the last 15 years or so, that Iowa in recent years has certainly become more open to various types of writing, and that even when Iowa's influence was at an apex, there were always other sorts of programs and writers out there — John Barth at Johns Hopkins, Robert Coover at Brown, and Donald Barthelme at the University of Texas are three he mentions, but even that list shows how narrow in other ways the writing programs were for so long: three white hetero guys with significant access to the NY publishing world.

What Bennett most convincingly shows is how the discourse of creative writing within U.S. universities from the beginning of the Cold War through at least to the 1990s created a field of limited, narrow values not only for what constitutes "good writing", but also for what constitutes "a good writer". It's a tale of parallel, and sometimes converging, aesthetics, politics, and pedagogies. Plenty of individual writers and teachers rejected or rebelled against this discourse, but for a long time it did what hegemonies do: it constructed common sense. (That common sense was not only in the workshops — at least some of it made its way out through writing handbooks, and can be seen to this day in pretty much all of the popular handbooks on how to write, including Stephen King's

On Writing.)

Some of the best material in

Workshops of Empire is not its Cold War revelations (most of which are known from previous scholarship) but in its careful limning of the tight connections between particular, now often forgotten, ideas from before the Cold War era and what became acceptable as "good writing" later. The first chapter, on the

"New Humanism", is revelatory, especially in how it draws a genealogy from

Irving Babbitt to Norman Foerster to

Paul Engle and

Wallace Stegner. Bennett tells the story of New Humanism as it relates to New Criticism and subsequently not just the development of workshop aesthetics, but of university English departments in the second half of the 20th century generally, with New Humanism adding a concern for ethical propriety ("the question of the relation of the goodness of the writing to the goodness of the writer") to New Criticism's cold formalism:

Whereas the New Criticism insisted on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the poem or story — every word counted — the New Humanism focused its attention on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the humanistic subject. It did so not as a kind of progressive-educational indulgence but in deference to the wholeness of the human person and accompanied by a strict sense of good conduct. (29-30)

This mix was especially appealing to the post-WWII world of anti-Communist liberalism, a world scarred by the horrors of Nazism and Stalinism, and a United States newly poised to inflict its empire of moral righteousness across the world.

For all of Bennett's gestures toward Marxism and anti-imperialism, he seems to share some basic assumptions about the power of literature with the men of the Cold War era he disdains as conservatives. In the book's conclusion, he writes:

It remains an open question just how much criticism some or all American MFA programs deserve for contributing to the impasse of neoliberalism — the collective American disinclination to think outside narrow ideological commitments that exacerbate — or at the very least preempt resistance to — the ugliest aspects of the global economy. Those narrow commitments center, above all, on an individualism, economic and otherwise, vastly more powerful in theory and public rhetoric than in fact. We encourage ourselves to believe that we matter more than we do and to go it alone more than we can. This unquestioned inflation of the personal begs, in my opinion, the kinds of questions that must be asked before any reform or solution to some seriously pressing problems looks likely to be found. (173)

This is almost comically self-important in its idea that MFA programs might (he hopes?) have enough cultural effect that if only they had been more willing to teach students to write like Thomas Wolfe and John Steinbeck, then maybe we could conquer neoliberalism! One moderately popular movie has more cultural effect than piles and piles of books written by even the famous MFA people. If you want to fight neoliberalism, your MFA and your PhD (from Harvard!) aren't likely to do anything, sorry to say. If you want to fight neoliberalism ... well, I don't know. I'm not convinced neoliberalism

can be fought, though we might be able to find

an occasional escape in aesthetics. The idea that Books Do Big Things In The World is one that Bennett shares with his subjects; he'd just prefer they read different books.

As self-justifying delusions go, I suppose there are worse, and all of us who spend our lives amidst writing and reading believe to some extent or another that it's worthwhile, or else we wouldn't do it. But "worthwhile" is far from "world-changing". (Rx: Take a couple

Wallace Shawn plays and call me in the morning.)

Despite this, Bennett's concluding chapter had me raising my fist in solidarity, because no matter what our personal tastes in fiction may be, no matter how much we may disagree about the extent to which writing can influence the world, we agree that writing pedagogy ought to be diverse and historically informed in its approach.

Bennett shows some of the forces that imposed a common shallowness:

There was, in the second wave of programs — the nearly fifty of them founded in the 1960s — little need to critique the canon and smash the icons. To the contrary, the new roster of writing programs could thrive in easy conscience. This was because each new seminar undertook to add to the canon by becoming the canon. The towering greats (Shakespeare, Milton, Whitman, Woolf, whoever) diminished in influence with each passing year, sharing ever more the icon's niche with contemporary writers. In 1945, in 1950, in 1955, prospective poets and novelists looked to the neverable pantheon as their competition. In 1980, in 1990, in 2015, they more often regarded their published teachers or peers as such. (132)

That's polemical, and as such likely hyperbolic, but it suggests some of the ways that some writing programs may have capitalized on the culture of narcissism that has only accelerated via social media and

is now ripe for economic exploitation. I don't think it's a crisis of the canon — moral panics over the Great Western Tradition are academic Trumpism — so much as a crisis of literary-historical knowledge. Aspiring writers who are uninterested in reading anything written before they were born are nincompoops. Understandably and forgiveably so, perhaps (U.S. culture is all about the current whizbang thing, and historical amnesia is central to the American project), but too much writing workshop pedagogy, at least of the recent past, has been geared toward encouraging nincompoopness. As Bennett suggests, this serves the interests of American empire while also serving the interests of the writing world. It domesticates writers and makes them good citizens of the nationalistic endeavor.

Within the context of the book, Bennett's generalizations are mostly earned. What was for me the most exciting chapter shows exactly the process of simplification and erasure he's talking about. That chapter is the final one before the conclusion: "Canonical Bedfellows: Ernest Hemingway and Henry James". Bennett's claim here is straightforward: The consensus for what makes writing "good" that held at least from the late 1940s to the end of the 20th century in typical writing workshops and the most popular writing handbooks was based on teachers' knowledge of Henry James's writing practices and everyone's veneration of Hemingway's stories and novels.

For Bennett, Hemingway became central to early creative writing pedagogy and ideology for three basic reasons: "he fused together a rebellious existential posture with a disciplined relationship to language, helping to reconcile the avant-garde impulse with the classroom", "he offered in his own writing...a set of practices with the luster of high art but the simplicity of any good heuristic", and "he contributed a fictional vision whose philosophical dimensions suited the postwar imperative to purge abstractions from literature" (144). Hemingway popularized and made accessible many of the innovations of more difficult or esoteric writers: a bit of Pound from Pound's Imagist phase, some of Stein's rhythms and diction, Sherwood Anderson's tone, some of the early Joyce's approach to word patterns... ("He was possibly the most derivative

sui generis author ever to write," Bennett says. Snap!) Hemingway's lifestyle was at least as alluring for post-WWII male writers and writing teachers as his writing style: he was macho, war-scarred, nature-besotted in a Romantic but also carnivorous way. He was no effete intellectual. If you go to school, man, go to school with Papa and you'll stay a man.

The effect was galvanizing and long-term:

Stegner believed that no "course in creative writing, whether self administered or offered by a school, could propose a better set of exercises" than this method of Hemingway's. Aspirants through to the present day have adopted Hemingway's manner on the page and in life. One can stop writing mid-sentence in order to return with momentum the following morning; aim to make one's stories the tips of icebergs; and refrain from drinking while writing but aim to drink a lot when not writing and sometimes in fact drink while writing as one suspects with good reason that Hemingway himself did, despite saying he didn't. One can cultivate a world-class bullshit detector, as Hemingway urged. One can eschew adverbs at the drop of a hat. These remain workshop mantras in the twenty-first century. (148)

Clinching the deal, the Hemingway aesthetic allowed writing to be gradeable, and thus helped workshops proliferate:

Hemingway's methods are readily hospitable to group application and communal judgment. A great challenge for the creative writing classroom is how to regulate an activity ... whose premise is the validity and importance of subjective accounts of experience. The notion of personal accuracy has to remain provisionally supreme. On what grounds does a teacher correct student choices? Hemingway offered an answer, taking prose style in a publicly comprehensible direction, one subject to analysis, judgment, and replication. ... One classmate can point to metaphors drawn from a reality too distant from the characters' worldview. Another can strike out those adverbs. (151)

Bennett then points out that the predecessors of the New Critics, the conservative Southern Agrarians, thought they'd found in Hemingway almost their ideal novelist (alas, he wasn't Southern). "The reactionary view of Hemingway," Bennett writes, "became the consensus orthodoxy." Hemingway's concrete details don't offer clear messages, and thus they allowed his work to be "universal" — and universalism was the ultimate goal not only of the Southern Agrarians, but of so many conservatives and liberals after WWII, when art and literature were seen as a means of uniting the world and thus defeating Communism and U.S. enemies. "Universal" didn't mean

actually universal in some equal exchange of ideas and beliefs — it meant imposing American ideals, expectations, and dreams across the globe. (And consequently opening up the world to American business.)

Such a discussion of how Hemingway influenced creative writing programs made me think of other ways complex writing was made appealing to broad audiences — for instance, much of what Bennett writes parallels with some of the ideas in work such as

Creating Faulkner's Reputation by Lawrence H. Schwartz and especially

William Faulkner: The Making of a Modernist, where Daniel Singal

proposes that Faulkner's alcoholism, and one alcohol-induced health crisis in November 1940 especially, turned the last 20 years of Faulkner's life and writing into not only a shadow of its former achievement, but a mirror of the (often conservative) critical consensus that built up around him through the 1940s. Faulkner became teachable, acceptable, "universal" in the eyes of even conservative critics, as well as in Faulkner's own pickled mind, which his famous

Nobel Prize banquet speech so perfectly shows.

(Thus some of my hesitation around Bennett's too easy use of the word "modernist" throughout

Workshop of Empire — the strain of Modernism he's talking about is a sanitized, domesticated, popularized, easy-listening Modernism. It's Hemingway, not Stein. It's late Faulkner, not

Absalom, Absalom!. It's white, macho-male, heterosexual, apolitical. The influence seems clear, but it chafes against my love of a broader, weirder Modernism to see it labeled only as "modernism" generally.)

Then there's Henry James. Not for the students, but the teachers:

As with Hemingway, James performed both an inner and an outer function for the discipline. In his prefaces and other essays, he established theories of modern fiction that legitimated its status as a discipline worthy of the university. Yet in his powers of parsing reality infinitesimally, James became an emblem similar to Hemingway, a practitioner of resolutely anti-Marxian fiction in an era starved for the same. (152)

Reducing the influence and appeal here to simply the anti-Marxian is a tic produced by Bennett's yearning for the return of the Popular Front, because his own evidence shows that the immense influence of Hemingway and James served not only to veer teachers, students, writers, and critics away from any whiff of agit-prop, but that it created an aesthetic not only hostile to Upton Sinclair but to the 19th century Decadents and Symbolists, to much of the Harlem Rennaissance, to most forms of popular literature, and to any writers who might seem too difficult, abstruse, or weird (imagine Samuel Beckett in a typical writing workshop!).

As Bennett makes clear, the

idea of Henry James's writing practice more than any of James's actual texts is what held through the decades. "He did at least five things for the discipline," Bennett says (152-153):

- His Prefaces assert the supremacy of the author, and "the early MFA programs depended above all on a faith that literary meaning could be stable and stabilized; that the author controlled the literary text, guaranteed its significance, and mastered the reader."

- James's approach was one of research and selection, which is highly appealing to research universities. Writing becomes a laboratory, the writer an experimenter who experiments succeed when the proper elements are selected and balanced. "He identified 'selection' as the major undertaking of the artist and perceived in the world a landscape without boundaries from which to do the selecting." Revision is key to the experiment, and revision should be limitless. Revision is virtue.

- James was anti-Romantic in a particular way: "James centered modern fiction on art rather than the artist, helping to shape the doctrines of impersonality so important to criticism from the 1920s through the 1950s. He insulated the aesthetic object from the deleterious encroachments of ego." Thus the object can be critiqued in the workshop, not the creator.

- "James nonetheless kept alive the romantic spirit of creative inspiration and drew a line between those who have it and those who don't." He often sounds mystical in his Prefaces (less so his Notebooks). The craft of writing can be taught, but the art of writing is the realm of genius.

- "James regarded writing as a profession and theorized it as one." The writer is someone who labors over material, and the integrity of the writer is equal to the integrity of the process, which leads to the integrity of the final text.

These ideas took hold and were replicated, passed down not only through workshops, but through numerous handbooks written for aspiring writers.

The effect, ultimately, Bennett asserts, was to stigmatize intellect. Writing must not be a process of thought, but a process of feeling. It must be sensory. "No ideas but in things!" A convenient ideology for times of political turmoil, certainly.

Semester after semester, handbook after handbook, professor after professor, the workshops were where, in the university, the senses were given pride of place, and this began as an ideological imperative. The emphasis on particularity, which remains ubiquitous today, inviolable as common sense, was a matter for debate as recently as 1935. The debate, in the 21st century, is largely over. (171)

I wonder. From writers and students I sense — and this is anecdotal, personal, sensory! — a desire for something more than the old Imagist ways. A desire for thought in fiction. For politics, but not a simple politics of vulgar Marxism. The ubiquity of dystopian fiction signals some of that, perhaps. Dystopian fiction is being written by both the hackiest of hacks and the highest of high lit folks. It shows a desire for imagination, but a particular sort of imagination: an imagination about society. Even at its most

personal, navel-gazing, comforting, and self-justifying, it's still at least trying to wrestle with more than the concrete, more than the story-iceberg.

So, too, the efflorescence of different types of writing programs and different types of teachers throughout the U.S. today suggests that the era of the aesthetic Bennett describes may be, if not over, at least far less hegemonic. Bennett cites its apex as somewhere around 1985, and that seems right to me. (I might bump it to 1988: the last full year of Reagan's presidency and the publication of Raymond Carver's selected stories,

Where I'm Calling From.) The people who graduated from the prestigious programs then went on to become the administrators later, but at this point most of them have retired or are close to retirement. There are still

narrow aesthetics, but there's plenty else going on. Most importantly, writers with quite different backgrounds from the old guard are becoming not just the teachers, but the administrators. Bennett notes that some of the criticism he received for

earlier versions of his ideas pointed to these changes:

I was especially convinced by the testimony of those who argued that the Iowa Writers' Workshop under Lan Samantha Chang's directorship has different from Frank Conroy's iteration of that program, which I attended in the late 1990s and whose atmosphere planted in my heart the suspicion that, for some reason, the field of artistic possibilities was being narrowed exactly where it should be broadest. In the twenty-first century, things have changed both at Iowa and at the many programs beyond Iowa, where few or none of my conclusions might have pertained in the first place. (163)

That's an important caveat there. The present is not the past, but the past contributed to the present, and it's a past that we're only now starting to recover.

There's much more to be investigated, as I'm sure Bennett knows. The role of the

Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and similar institutions would add some more detail to the study; similarly, I think someone needs to write about the intersections of creative writing programs and composition/rhetoric programs in the second half of the twentieth century. (Much more needs to be written about CUNY during

Mina Shaughnessy's time there, for instance, or about

Teachers & Writers.) But the value of Bennett's book is that it shows us that many of the ideas about what makes writing (and writers) "good" can be — should be — historicized. Such ideas aren't timeless and universal, and they didn't come from nowhere. Bennett provides a map to some of the wheres from whence they came.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 12/10/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

writer,

Books,

quiz,

History,

Literature,

Poet,

America,

T.S. Eliot,

British,

modernism,

w b yeats,

james joyce,

tragedy,

american literature,

ezra pound,

fascism,

*Featured,

Ford Madox Ford,

UKpophistory,

Wyndham Lewis,

Quizzes & Polls,

Arts & Humanities,

David Moody,

Ezra Pound: Poet,

Modernist Literature,

The Epic Years,

volume III,

Add a tag

Ezra Pound was a major figure in the early modernist movement. During his lifetime he developed close interactions with leading writers and artists, such as Yeats, Ford, Joyce, Lewis, and Eliot. Yet his life was marked by controversy and tragedy, especially during his later years.

The post How well do you know Ezra Pound? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

It is far too early to tear down the barricades. Dancing shoes will not do. We still need our heavy boots and mine detectors.

—Jane Marcus, "Storming the Toolshed"

1. Seeking Refuge in Feminist Revolutions in ModernismLast week, I spent two days at the

Modernist Studies Association conference in Boston. I hadn't really been sure that I was going to go. I hemmed and hawed. I'd missed the call for papers, so hadn't even had a chance to possibly get on a panel or into a seminar. Conferences bring out about 742 different social anxieties that make their home in my backbrain. I would only know one or maybe two people there. Should I really spend the money on conference fees for a conference I was highly ambivalent about? I hemmed. I hawed.

In the end, though, I went, mostly because my advisor would be part of a seminar session honoring the late

Jane Marcus, who had been her advisor. (I think of Marcus now as my grandadvisor, for multiple reasons, as will become clear soon.) The session was titled "Thinking Back Through Our Mothers: Feminist Revolutions in Modernism", the title being an homage to Marcus's essay "Thinking Back Through Our Mothers" from the 1981 anthology

New Feminist Essays on Virginia Woolf, itself an homage to the phrase in Woolf's

A Room of One's Own. Various former students and colleagues of Marcus would circulate papers among themselves, then discuss them together at the seminar. Because of the mechanics of seminars, participants need to sign up fairly early, and I'd only registered for the conference itself a few days before it began, so there wasn't even any guarantee I'd been able to observe; outside participation is at the discretion of the seminar leader. Thankfully, the seminar leader allowed three of us to join as observers. (I'm trying not to use any names here, simply because of the nature of a seminar. I haven't asked anybody if I can talk about them, and seminars are not public, though the participants are listed in the conference program.)

Marcus was a socialist feminist who was very concerned with bringing people to the table, whether metaphorical or literal, and so of course nobody in the seminar would put up with the auditors being out on the margins, and they insisted that we sit at the table and introduce ourselves. Without knowing it, I sat next to a senior scholar in the field whose work has been central to my own. I'd never seen a picture of her, and to my eyes she looked young enough to be a grad student (the older I get, the younger everybody else gets!). When she introduced herself, I became little more than a fanboy for a moment, and it took all the self-control I could muster not to blurt out some ridiculousness like, "I just love you!" Thankfully, the seminar got started and then there was too much to think about for my inner fanboy to unleash himself. (I did tell her afterwards how useful her work had been to me, because that just seemed polite. Even senior scholars spent a lot of hours working in solitude and obscurity, wondering if their often esoteric efforts will ever be of any use to anybody. I wanted her to knows that hers had.) It soon became the single best event I've ever attended at an academic conference.

|

| Jane Marcus |

To explain why, and to get to the bigger questions I want to address here, I have to take a bit of a tangent to talk briefly about a couple of other events.

The day before the Marcus seminar, I'd attended a terrible panel. The papers that were about things I knew about seemed shallow to me, and the papers not about things I knew about seemed like pointless wankery. I seriously thought about just going home. "These are not my people," I thought. "I do not want to be in their academic world."

I also attended a "keynote roundtable" session where three scholars — Heather K. Love, Janet Lyon, and Tavia Nyong’o — discussed the theme of the conference: modernism and revolution. Sort of. It was an odd event, where Love and Nyong'o were in conversation with each other and Janet Lyon was a bit marginalized, simply because her concerns were somewhat different from Love and Nyong'o's and she hadn't been part of what is apparently a longstanding discussion between them. I mention this not as criticism, really, because though the side-lining of Lyon felt weird and sometimes awkward, the discussion was nonetheless interesting and vexing in a productive way. (I know Love and Nyong'o's work, and appreciate it a lot.) I especially appreciated their ideas about academia as, ideally, a refuge for some types of people who lack a space in other institutions and have been marginalized by ruling powers, even if there are no real solutions, given how deeply infused with ideas of finance and "usefulness" the contemporary university is, how exploitative are the practices of even small schools. (Nyong'o works at NYU, an institution that has become

the mascot for neoliberalism. His recent blog essay

"The Student Demand" is important reading, and was referenced a number of times during the roundtable.) As schools make more and more destructive decisions at the level of administration and without the faculty having much obvious ability to challenge them, the position of the tenure-tracked, salaried faculty member of conscience is difficult, for all sorts of reasons I won't go into here. As Nyong'o and Love pointed out, the moral position must often be that of a criminal in your own institution.

All of this was on my mind the next day as I listened to discussions of Jane Marcus. After the seminar, some of us went out to lunch together and the discussion continued. What I kept thinking about was the idea of refuge, and the way that certain traditions of teaching and writing have opened up spaces of refuge within spaces of hostility. Marcus stands as an exemplar here, both in her writing and her pedagogy. The question everyone kept coming back to was: How do we continue that work?

In her 1982 essay "Storming the Toolshed", Marcus reflected on the position of various feminist critics ("lupines" — she appropriated Quentin Bell's dismissive term for feminist Woolfians, reminding us that it is also a name for a

flower):

Feminists often feel forced by economic realities to choose other methodologies and structures that will ensure sympathetic readings from university presses.We may be as middle class as Virginia Woolf, but few of us have the economic security her aunt Caroline Emelia Stephen's legacy gave her. The samizdat circulation among networks of feminist critics works only in a system where repression is equal. If all the members are unemployed or underemployed, unpublished or unrecognized, sisterhood flourishes, and sharing is a source of strength. When we all compete for one job or when one lupine grows bigger and bluer than her sisters with unnatural fertilizers from the establishment, the ranks thin out. Times are hard and getting harder.

Listening to her students and colleagues remember her, I was struck by how well Marcus had tended her own garden, how well she had tried to keep it from being fatally poisoned by the unnatural fertilizers of the institutions of which she was a part. She found opportunities for her students to research and publish in all sorts of places, she supported scholars she admired, and when she couldn't find opportunities for other people's work, she did was she could to create them. She was tenacious, dogged, sometimes even insufferable. This clearly did not always lead to the easiest of relationships, even with some of her best friends and favorite students. As with so many brilliant people, her virtues were intimately linked to her faults. Jane Marcus without her faults would not have been Jane Marcus. Faults and all ("I've never been so mad at somebody!"; "We didn't speak to each other for a year"), again and again people said: "Jane gave me my life."

There seemed to be a sense among the seminar participants that the sort of politically-committed, class-conscious feminism that Marcus so proudly stood for is on the wane in academia, and that while the field of modernist studies may be more open to marginalized writers than it was 30 or 40 years ago, the teaching of modernism in university classes remains very male, very Eliot-Pound-Joyce, with a bit of Woolf thrown in as appeasement to the hysterics. (I have no idea whether this is generally accurate, as I have not done any study of what's getting taught in classes that cover modernist stuffs, but it was the specific experience of a number of people at the conference.) Since the late '90s, there's been the historically-minded New Modernist Studies*, but the question keeps coming up: Does the New Modernist Studies do away with gender ... and if so, is the New Modernist Studies a throwback to the pre-feminist days? Anne Fernald looked at the state of things in the introduction to the

2013 issue of Modern Fiction Studies that she edited, an issue devoted to women writers:

The historical turn has revitalized modernist studies. Beginning in the late 1990s, its impact continues in new book series from Oxford and Columbia University Presses; in the Modernist Studies Association (MSA), whose annual conference has attracted hundreds of scholars; and in burgeoning digital archives such as the Modernist Journals Project. Nonetheless, one hallmark of the new modernist studies has been its lack of serious interest in women writers. Mfs has consistently published feminist work on and by women writers, including special issues on Spark, Bowen, Woolf, and Stein; still, this is the journal’s first issue on feminism as such in nineteen years. Modernism/modernity, the flagship journal of the new modernism and the MSA, has not, in nineteen years, devoted a special issue to a women writer or to feminist theory. Only eight essays in that journal have “feminist” or “feminism” as a key term, while an additional twenty-six have “women” as a key term. And, although The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms includes many women contributors, only one of the twenty-eight chapters mentions women in its title, and, of the six authors mentioned by name, only one—Jean Rhys—is a woman.

Similarly, Marcus's socialism and Marxism may not be especially welcome among the New Modernists, for as Max Brzezinski polemically suggests in

"The New Modernist Studies: What's Left of Political Formalism?", the

New in

New Modernist Studies could easily slip into the

neo in

neo-liberal.

For scholars who have at least some sympathy with Marcus's political stance, there's a lot of deja vu, even weariness. How long, they wonder, must the same battles be fought?

For once, I'm not as pessimistic as other people. Routledge is launching a new journal of feminist modernism (with Anne Fernald as co-editor). Within the world of Virginia Woolf studies, much attention is being paid to Woolf's connections to anti-colonialism and to her ever-more-interesting writings in the last decade of her life. There is a strong transnational and postcolonial tendency among many scholars of modernism of exactly the sort that Marcus herself called for and exemplified, particularly in her later writings. Vigilance is necessary, but vigilance is always necessary. Networks of scholars and traditions of inquiry that Marcus participated in, contributed to, and in some cases founded remain strong.

As some of the people at the conference lamented the steps backward to regressive, patriarchal views, I thought of how lucky I've been in how I've learned to read and perceive this undefinable thing we call "modernism". The modernisms I perceive are ones where women are central. The Joyce-Pound-Eliot modernism is one I'm familiar with, but not one I think of first.

2. ForemothersI discovered Woolf right around the time I discovered Joyce and Kafka. I was too young (12 or 13) to understand any of their work in any meaningful way, but something about them fascinated me. I flipped through their books, which I found at the local college library. I read Kafka's shortest stories. I memorized the first few lines of

Finnegans Wake, though never managed to get more than a few pages into the book itself. I read

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, enjoying the first chapter very much and not getting a lot from the later ones (I still don't, honestly. My tastes aren't Catholic enough). I skimmed the last section of

Ulysses, looking to see how Joyce made Molly Bloom's stream of consciousness work. And then I read the first few pages of

Mrs. Dalloway. That wasn't a library book, but a book I bought with my scant bits of allowance money, saved up for probably a month. It was a mass market paperback with a bright yellow cover. I read the first 50 or so pages of the book and found it enthralling and perplexing. It ended up being too much for me. But there was something there. The first paragraphs were among the most beautiful things I'd ever read.

Skip ahead five or six years and I'm a student at NYU, studying Dramatic Writing. A friend I respect exhorts me to take a course with Ilse Dusoir Lind, who has mostly retired but comes back now and then to teach a seminar, this term on Faulkner and Hemingway. She wrote some of the earliest critical articles on Faulkner and, she later tells me, helped found the Women's Studies program at NYU. My friend was right: her class is remarkable. I don't much like Hemingway except for some of his short stories, but she takes us through

The Sun Also Rises, various stories, and

The Garden of Eden with panache. (I particularly remember how ridiculous and yet captivating she thought

The Garden of Eden was.) And then of course Faulkner, her great love. She taught us to read

The Sound and the Fury and

Absalom, Absalom!, for which I will always be grateful. Thus, my first experience of academic modernism was an experience of two of the most major of major modernist men seen through the eyes of a brilliant woman.

Skip ahead a year or so later and I've just finished my junior year of college. I've decided to transfer from NYU to UNH for various reasons. It's a tough summer for me, a summer of reckoning with myself and my world. I work at the

Plymouth State College bookstore, a place I've worked on and off for a number of summers since middle school. That June, the College is hosting the

International Virginia Woolf Society's annual conference, organized by a relatively new member of the PSC English Department,

Jeanne Dubino. My colleagues at the bookstore are all working as volunteers at the conference. They introduce me to Jeanne and I join the ranks of the volunteers. The bookstore goes all-out with displays. We stock pretty much every book by and about Woolf in print in the US. I remember opening the boxes and helping to shelve the books. None of us were efficient at shelving because we couldn't stop looking at the books.

Hermione Lee's

biography had just come out and we hung a giant poster of it up. I bought a copy (35% employee discount!) and began to devour it. One night, I was working the registration desk. Hermione Lee came in. She was giving the keynote address. She was late, having been delayed by weather or something. She was tired, but friendy. "Can I still get my registration materials?" she asked. "Certainly," I said. "And might I ask you to sign my book in return?" She laughed, said of course, and did so while I finished with her paperwork.

I found the conference enthralling. I never wanted to go home. (My parents had just divorced; being at the conference was much more fun than being at the house with my father.) The passion of the participants was contagious. Jeanne was astoundingly composed and friendly for someone in charge of a whole academic conference, and we continued to talk about Woolf now and then until she left Plymouth for other climes. I got to know Woolf because I got to know Jeanne.

Skip forward 6 months to the spring term of my senior year at UNH. By some bit of luck and magic, the English Department offered an upper-level seminar on Woolf this term and I was able to fit it into my schedule. I was the only male in the class, and relatively early on one of the other students said to me, in a tone of voice reserved for a rare and yet quite unappealing insect, "Why are you here?" (What did I reply? I don't remember. I probably said because I like Woolf. Or maybe: Why not?) The instructor was Jean Kennard. We read all of the novels except

Night and Day, plus we read

A Room of One's Own,

Three Guineas, and numerous essays. It was one of the hardest courses I've ever taken, either undergrad or grad, and one of the best. It exhausted me to the bone, and yet I wouldn't have wanted it to do anything less. Few courses have ever stayed with me so well or let me draw on what I learned in them for so long. Prof. Kennard was exacting, interesting, and intimidatingly knowledgeable. I didn't dare read with anything less than close attention and care, even if that meant not sleeping much during the term, because I feared she would ask me a question in class and I would be unprepared and give a terrible answer, and there was no way I was going to allow myself to do that because I already identified as someone for whom Virginia Woolf's work was important. I figured either I'd do well in the class or I'd collapse and be put on medical leave. (I had other classes, of course, and I was acting in some plays, and there was a bit of work on the side to give me some income, so not many free hours for sleeping.)

In the days of the

LitBlog Co-op in the early 2000s, I met

Anne Fernald. I didn't know she was a Woolfian or involved in modernist studies; I knew her as a blogger. Eventually, we talked about Woolf. (When I moved to New Jersey in the summer of 2007, Anne gave me a tour of the area. I remember asking her how

work on a critical edition of

Mrs. Dalloway was coming, naively expecting that work must be almost done. We had to wait a few more years. It was worth the wait.)

I didn't really encounter modernism in a classroom again until recently, because it wasn't a part of my master's degree work, except peripherally in that to study Samuel Delany's influences, which I did for the master's thesis, meant to study a lot of modernism, though modernism through his eyes. But his eyes are those of a black, queer man influenced by many women and committed to feminism, so once again my view of modernism was not that of the patriarchal white order, even though plenty of white guys were important to it.

And then PhD classes and research, where once again women were central. (It was in one such class that I first read Jane Marcus's

Hearts of Darkness: White Women Write Race.)

Thus, this quick overview of my own journey is a story of women and modernism. My own learning is very much the product of the sorts of efforts that Marcus and other feminist modernists made possible, the work they devoted their lives to. They are my foremothers, and the foremothers of so many other people as well. My experience may be unique in its weird bouncing across geographies and decades and media (I've never been very good at planning my life), but I hope it is not uncommon.

3. Reading MarcusI've been reading lots of Jane Marcus for the last month or so. Previously, I'd only read

Hearts of Darkness and a couple of the most famous earlier essays. Now, though, I've been combing through books and databases in search of her work. (At the MSA seminar, someone who had had to submit Marcus's CV for a grant application said it was 45 pages long. She published hundreds of essays and review-essays in addition to her books.)

I'm tempted to drop lots of quotes here — Marcus is eminently quotable. But perhaps a better use of this space would be to think about Marcus's own style of writing and thinking, the way she formed and organized her essays, which, much like Woolf's many essays, show a process of thought in development.

At the end of the first chapter of

Hearts of Darkness, which collects some of her more recent work, Marcus writes:

The effort of these essays is toward an understanding of what marks the text in its context, to hear the humming noise whose rhythm alerts us to the time and place that produced it, as well as the edgy avant-garde tones of its projection into the modernist future. For modernism has had much more of a future than one could have imagined. In a new century the questions still before me concern the responsibility for writing those once vilified texts into classic status in a new social imaginary. If it was once the critic's role to argue the case for canonizing such works, perhaps it is now her role to question their status and explore their limits.

This statement concisely maps the direction of Marcus's thinking over the course of her career. Her efforts were first to recover texts that had fallen out of the sight of even the most serious of readers, then to advocate for those texts' merits, then to convince her students and colleagues to add those texts to curricula and, in many cases, to help bring them back into print. She argued, for instance, for a particular version of Virginia Woolf, one at odds with a common presentation of Woolf as fragile and apolitical and sensitive and tragic. Marcus was having none of that. Woolf was a remarkably strong woman, a nuanced political thinker whose ideas developed significantly over time and came to a kind of fruition in the 1930s, and a far more complex artist than she was said to be. Later, though, Marcus didn't need Woolf to be quite so much of a hero. She was still all the things she had been before, but she was also flawed, particularly when it came to race. The Woolf that Marcus looks at in

"'A Very Fine Negress'" and

"Britannia Rules The Waves" is in many ways an even more interesting Woolf than in Marcus's earlier writings, because she is still a Woolf of immense depth but also immense contradictions and blind spots and very human failures of perception and sympathy. Marcus's earlier Woolf is Wonder Woman (though one too often mistaken for a mousy, oversensitive, snobby, mentally ill

Diana Prince), but her later Woolf is more like a brilliant, frustrating friend; someone striving to overcome all sorts of circumstances, someone capable of the most beautiful creations and insights, and yet also sometimes crushingly disappointing, sometimes even embarrassing. A human Woolf from whom we can learn so much about our own human failings. After all, if someone as remarkable as Woolf could be so flawed in some of her perceptions, what about us? In exploring the limits and questioning the status of the works we once needed to argue into the mainstream conversation, we also remind ourselves of our own limits, and perhaps we develop better tools with which to question our own status in whatever places, times, and circumstances we happen to inhabit.

This is not to say that Marcus's early work is irrelevant. Not at all. It is still quite thrilling to read, and rich with necessary insights. (If anything, it does make me sad that a number of her best, most cutting insights about academia and power relations remain fresh today. There's been progress, yes, but not nearly enough, and much that was bad in the past repeats and repeats into our future.) Here's an example, from

a May 1987 review in the Women's Review of Books of

E. Sylvia Pankhurst: Portrait of a Radical by Patricia Romero, a book Marcus thought misrepresented and misinterpreted its subject. Near the end, after detailing all the ways Romero fails Pankhurst, Marcus makes a sharp joke:

Sylvia Pankhurst has had her come-uppance so many times in this book that there's hardly anywhere for her to come down to. Romero says that she met her husband on the same day that she met Sylvia Pankhurst's statue in Ethiopia. One hopes that he fared better than Sylvia.

Ouch. But this joke serves as a conclusion to the litany of Romero's failures as Marcus saw them and turns then to a larger point:

Let it be clear that I am not calling for nurturant biographies of feminist heroines. I, too, as a student of suffrage, have several bones to pick with Sylvia Pankhurst. In writing The Suffragette Movement she not only distorted history to aggrandize the role of working-class suffragettes in winning the vote, but, more importantly, she wrote the script of the suffrage struggle as a family romance, a public Cinderella story with her mother and sister cast as the Wicked Stepmother and Stepsister. It was this script which provided George Dangerfield and almost every subsequent historian of suffrage with the materials for reading the movement as a comedy. Sylvia provided them with a false class analysis which persists. Patricia Romero now unwittingly wears the mantle woven by Sylvia Pankhurst as the historian so bent on the ruthless exposure of her subject that she gives the enemies of women another hysteric to batter — though the prim biographer would doubtless be horrified at the suggestion that the Sylvia Pankhurst whom she despises and exposes was engaged in a project similar to her own and is, in fact, her predecessor.

Such an amazingly rich paragraph! The review up to now has been Marcus showing the ways that she thinks Romero misrepresents Sylvia Pankhurst, and the effect is mostly to make us think Marcus venerates Pankhurst totally and is defending the honor of a hero against a detractor. But no. Her message is that feminist history deserves better: it deserves accuracy.

Both Romero and Pankhurst failed this imperative by letting their ideologies and prejudices hide and mangle nuances. Both Romero and Pankhurst, wittingly or unwittingly, presented the deadly serious history of the suffrage movement as comedy. Both, wittingly or unwittingly, provided cover and even ammunition for misogynistic discourse. And that, ultimately, is the argument of Marcus's review. She sees her job as a reviewer not to be someone who gives thumbs up or thumbs down, but to be someone who can analyze what sort of conversation the book under review enters into and supports. The limitations she sees in the book are not just the limitations of one book, but limitations endemic to an entire way of presenting history.

She then brings the review back to Pankhurst and Romero's portrait of her, and now we as readers can appreciate a larger vantage to the evaluation, because we know it's not just about this book, but about historiography and feminism. Marcus mentions some other, better books (a hallmark of her reviews: she never leaves the reader wondering what else there is to read — in negative reviews such as this one, it's books that do a better job; in positive reviews, it's other books that contribute valuable knowledge to the conversation), then:

The problem with the historian's project of setting the record straight is that it flourishes best with a crooked record, the crookeder the better. Romero has found in Sylvia Pankhurst's life the perfect crooked record to suit her own iconoclastic urge.

We might think that Marcus here is holding herself apart from "the historian's project of setting the record straight", that she is setting herself up as somehow perfect in her own sensibilities. But in the next sentence she shows that is not the case:

Admitting one's own complicity as a feminist in all such iconoclastic activity, one is still disappointed in the results. I came to this book anticipating with a certain relish the pleasure of seeing Sylvia Pankhurst put in her place. But because the author writes with such contempt for her subject as well as for activism of all kinds, I came away with a deep respect for Sylvia Pankhurst and the work she did for social justice.

To be a feminist is to be iconoclastic. To be a feminist is to be faced with many crooked records. But this book can serve, Marcus seems to be saying, a warning of what can happen when the desire to be an iconoclast overcomes the desire to be accurate, and when one is tempted to add some crooks to the record before straightening it out. The danger is clearly implied: Beware that you do not depart too far from accuracy, lest you lead your reader to the opposite of the conclusions you want to impart.

Marcus would have been a wonderful blogger. Her writing style is discursive, filled with offhand references that would make for marvelous hyperlinks, and she doesn't waste a lot of time on transitions between ideas. At the MSA seminar, someone said that Marcus's process was to write lots of fragments and then edit them together when she needed a paper. Her writing is a kind of assemblage, both in the sense of

Duchamp et al. and of

Deleuze & Guattari.

(In the course where we read

Hearts of Darkness, one of the other students pointed out that Marcus jumps all over the place and rarely seems to have a clear thesis — her ideas are accumulative, sometimes tangential, a series of insights working together toward an intellectual symphony. If we were to write like that, this student said, wouldn't we just get criticized for lack of focus, wouldn't our work be rejected by all the academic publishers we so desperately need to please if we are to have any hope of getting jobs or tenure? "She can write like that," our instructor said, "because she's Jane Marcus." Which in many ways is true. We read Jane Marcus to follow the lines of thought that Jane Marcus writes. It's hard to start out writing like that, but once you have a reputation, once your work is read because of your byline and not just because of your subject matter, you have more freedom of form. And yet I also think we should be working toward a world that allows and perhaps even encourages such writing, regardless of fame. Too many academic essays I read are distorted by the obsession with having a central claim; they sacrifice insight for repetitious metalanguage and constant drumbeating of The Major Point. It's no fun to read and it makes the writing feel like a tedious explication of the essay's own abstract. Marcus's writing has the verve, energy, and surprise of good essayistic writing. This was quite deliberate on her part — see her comments in

"Still Practice, A/Wrested Alphabet: Toward a Feminist Aesthetic" on Woolf as an essayist versus so many contemporary theorists. I don't entirely agree with her argument, since I don't think "difficult" writing should only be the province of "creative writers" and not critics, but I'd also much prefer that writers who are not geniuses aspire to write more like Woolf in her essays than like Derrida. And the insistence that academic writers build Swamp Thing jargonmonsters to prove their bona fides is ridiculous.)

Her discursive, sometimes rambling style serves Marcus well because it allows her to connect ideas that might otherwise get left by the wayside. Marcus makes the essay form do what it is best at doing. Her 1997 essay

"Working Lips, Breaking Hearts: Class Acts in American Feminism" masterfully demonstrates this. At its most basic level, the essay is a review (or, as Marcus says, "a reading") of

Listening to Silences: New Essays in Feminist Criticism, which builds off of the work of Tillie Olsen, particularly her invaluable book

Silences. But Marcus's essay is far more than just a look at this one anthology — it is also a tribute to

Tillie Olsen, who herself influenced Marcus tremendously, a study of feminist-socialist theory and history, a manifesto about canons and canonicity, a personal memoir, and even, in one moving footnote, an obituary for Constance Coiner, a feminist scholar who died in the crash of

TWA flight 800.

By writing about Olsen, a generation her elder, Marcus is able to take a long view of American feminism, its past and future. She's writing just as the feminists of the 1970s are becoming elders themselves and a new generation of feminists is moving the cause into new directions, often without sufficient attention to history. Discussing one of the essays in

Listening to Silences, she writes:

More troublesome (or perhaps merely more difficult for me to see because of my own positionality) is Carla Kaplan's claim that my generation of American feminist critics used a reading model "based on identification of reader and heroine, and it tended to ignore class and race differences among women" (10). She assumes that the generation influenced by Olsen always produced such limited readings of exemplary texts — Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper", Susan Glaspell's "A Jury of Her Peers", and Isak Dinesen's "The Blank Page" — without acknowledging that there was a strong and vocal objection to reading these texts historically as merely embodying the interests of certain feminist critics themselves. I know I was not alone in choosing never to teach them. (I have often said that these texts were chosen because they reflected the experience of feminists in the academy.) In addition, it seems important to make clear that the differences among women made by race, class, and sexual orientation were marked by many critics at the time (always by Gayatri Spivak and Lillian Robinson, e.g., and often by other nonmainstream feminist critics). There is a real danger in essentializing the work of a whole generation of feminists.

What Marcus repeatedly did for the history of British modernism, especially in the 1930s, she here does for the history of the movement she herself was part of: She calls for us not to reduce the history to a single tendency, not to make the participants into clones and drones. She acknowledges that some feminists in the 1970s and 1980s read from a place of self-identification, oblivious to race and class, but exhorts us to remember that not everyone did, and that in fact there was discussion among feminists not only about race and class, but about how to read as a feminist. She doesn't want to see her own generation and movement reduced to stereotypes in the way the British writers of the 1930s especially were. Throughout

Hearts of Darkness, she writes about

Nancy Cunard, first to overcome the many slanders of Cunard over the decades, but also to offer a useful contrast with Woolf in terms of racial perceptions and desires. She wants attention to

Claude McKay and

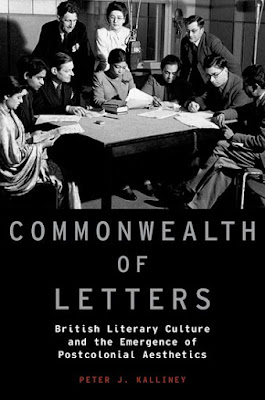

Mulk Raj Anand because only reading white and mostly male writers distorts history, which distorts our perception of ourselves: "It is my opinion that the study of the period would be greatly enriched by wresting it from the hands of those who leave out the women and the people of color who were active in the struggle for social change in Britain. It is important for students to know that leftists in the thirties were not all leviathans on the questions of race, gender, and class. Not all their hearts were dark. ...the critics before us deliberately left us in the dark about the presence of black and South Asian intellectuals on the cultural scene" (181). (Peter Kalliney's recent

Commonwealth of Letters does some of the work of tracing these networks, and

Anna Snaith has done exemplary work in and around all of this.)

"Working Lips, Breaking Hearts" brings all of these interests together, and does so not only for British and U.S. writers and activists of the 1930s, but also for Marcus's own generation of feminists.

This is our history, she seems to say,

and we must take care of it, or else what was done to the people of the 1930s by historians and literary critics will be done to us.

In

"Suptionpremises", a blistering 2002 review-essay about critics' interpretations of whites' uses of black culture in the 1920s and 1930s, Marcus wrote:

Why should cross-racial identification with the oppressed be perceived as evil? Certainly, while it was both romantic and revolutionary and very much of the period, such love for the Other is not in itself a social evil. The embrace of the Other and the Other’s values and the Other’s arts, language, and music, has often been progressive. Interracial sex and interracial politics were and are important to any radical cultural agenda. Cunard and [Carl] Van Vechten were not sleeping with the enemy. One might even say that the bed, the barricade, the studio, and the boîte, or Paris nightclub, were the sites where the barriers to progressive human behavior were broken down.

But the mistaking of those whites who loved blacks, however motivated by desire, politics, or by sheer pleasure at hearing the music and seeing the extraordinary art of another people, as merely a set of cultural thieves does not contribute to our understanding of the cultural forces at work here.

The cultural forces at work were ones Marcus begins to see as queer:

The fear that motivates [critics] North, Douglas, and Gubar is the taint of the sexually perverse. What is the fear that motivates Archer-Straw and Bernard? Is it fear of the damage done to the stability of the black family and the wholeness of black art by the attention of queer white men and white women who broke the sexual race barrier? If we try to look at this from outside the separatist anxieties that are awakened on both sides of the color line by these early personal and political crossings, the modernist figures represent a rare coming together of radical politics, African and African American art and culture, and white internationalist avant-garde and Surrealist intellectuals. These encounters deserve attention as a queer moment in cultural history and I think that is the only way to get beyond the impasse of discomfort about the modernist race pioneers in our current critical thinking. If it is because of a certain liberated queer sexuality that certain figures could cross the color line, could try to speak black slang, however silly it sounded, then sex will have to take its place as a major component in the translation of ideas.

As she so often did, Marcus pays attention here to what she thinks are the forces and desires that construct certain interpretations. "Why this?" she asks again and again, "and why now?" What sort of work do these kinds of interpretations do, whom do they help and whom do they hurt, what do they make visible and what do they leave invisible? What social or personal need do they seem to serve? And then the implied question: Whom do my own interpretations help or hurt? What do I make visible or invisible by offering such an interpretation?

One of Marcus's masterpieces was not a book she wrote herself, but

an annotated edition of Woolf's Three Guineas that she edited for Harcourt, published in 2006.

Three Guineas had not been served well by most critics and editors over the years, and Marcus's edition was the first American edition to include the photographs Woolf originally included, but which, for reasons no-one I know of has been able to figure out, were dropped from all printings of the book after Woolf's death. Marcus provided a 35-page introduction, excerpts from Woolf's scrapbooks, annotations that sometimes become mini-essays of their own, and an annotated bibliography. It's a model of a scholarly edition aimed at common readers (as opposed to a scholarly edition aimed at scholars, which is a different [and also necessary] beast, e.g. the

Shakespeare Head editions and the

Cambridge editions of Woolf). (She had already laid out her principles for such Woolf editions in a jaunty, often funny, utterly overstuffed, and quite generous

review of [primarily] Oxford and Penguin editions in 1994, and it seems to me that we can feel her chomping at the bit to do one of her own.)

Three Guineas is in many ways the key text for Marcus, a book overlooked and scorned, even hated, but which she finds immense meaning in. Her annotated edition allows her to show exactly what meanings within the text so deeply affected her. It's a great gift, this edition, because it not only gives us a very good edition of an important book, but it lets us read along with Jane Marcus.

It's unfortunate that Marcus never got to realize her dream of a complete and unbowdlerized edition of Cunard's

Negro anthology. Copyright law probably makes re-issuing the book an impossible task for at least another generation, given how many writers and artists it includes, although perhaps a publisher in a country with less absurd copyright regulations than the US could do it. (Aside: This is yet another example of how long copyright extensions destroy cultural knowledge.) Even the highly edited

version from 1970 is now out of print, though given how Marcus blamed that edition for many misinterpretations of Cunard and her work, I doubt she'd be mourning its loss. I wish somebody could create a digital edition, at least. Even an illegal digital edition. Indeed, that would perhaps be most in the spirit of the original text and of Marcus — somebody should get hold of a copy of the first edition, scan it, and upload it to

Pirate Bay. We need to be criminals in our institutions, after all...

4. Refuge and the CriminalLet us go then, you and I, back to where we began: refuge and revolutions.

"the numbers show that the teaching staff at America's universities are much whiter and much more male than the general population, with Hispanics and African Americans especially underrepresented. At some schools, like Harvard, Stanford, the University of Michigan, and Princeton, there are more foreign teachers than Hispanic and black teachers combined. The Ivy League's gender stats are particularly damning; men make up 68 percent and 70 percent of the teaching staff at Harvard and Princeton, respectively."

—Mother Jones, 23 November 2015

(Somewhere, Jane Marcus says that we may have to work and live in institutions, but that doesn't mean we have to

like them.)

"Experts think that the more than $1.3 trillion in outstanding education debt in the U.S. is more than that of the rest of the world combined."

—Bloomberg, 13 October 2015

My own assemblage here breaks down, because I have no conclusions, only impressions and questions.

Right now we are in the midst of a humanitarian crisis,

a refugee crisis. In my own state of New Hampshire, the Democratic governor, Maggie Hassan,

said there should be a halt to accepting all refugees from Syria. It is an ignorant and immoral statement. Maggie Hassan is a typical centrist Democrat, always rushing to put disempowered people in the middle of the road to get run over by the monster trucks of the ruling class.

"Since Sept. 11, 2001, nearly twice as many people have been killed by white supremacists, antigovernment fanatics and other non-Muslim extremists than by radical Muslims: 48 have been killed by extremists who are not Muslim, including the recent mass killing in Charleston, S.C., compared with 26 by self-proclaimed jihadists, according to a count by New America, a Washington research center."

—NYT, 24 June 2015

Yesterday (as I write this),

a man walked into a Planned Parenthood clinic with a gun. He killed three people before police were able to take him into custody. It was an act of terrorism, but will seldom be labelled that. Maggie Hassan will not call for middle-aged white men with beards to be barred from entry.

"The Republicans also organized a gun-buyer’s club, meeting in a conference room during work hours to design custom-made, monogrammed, silver-plated 'Tiffany-style' Glock 9 mm semi-automatic pistols."

—Slate, 24 November 2015

As I write this,

U.S. police officers have killed 1,033 people this year, including 204 unarmed people. The shooter at the Planned Parenthood clinic is very lucky to be alive. This proves it is actually possible for U.S. police not to kill people they intend to take into custody, even when they're armed. If the shooter had been a black man, though, I expect he would be dead right now.

"'We are locked and loaded,' he says, holding up a black 1911-style pistol. As he flashes the gun, he explains amid racial slurs that the men are headed to the Black Lives Matter protest outside Minneapolis’ Fourth Precinct police headquarters. Their mission, he says, is 'a little reverse cultural enriching.'"

—Minneapolis Star Tribune, 25 November 2015

Laquan McDonald had a small folding knife and was running away.

16 bullets took him down.

(Have you seen

M.I.A.'s new video, "Borders"? You should.)

(What can we use, too, from

Wendy Brown's recent discussion of rifts over gender and womanhood? What is getting lost, and what is newly seen?)

"The year-to-date temperature across global land and ocean surfaces was 1.55°F (0.86°C) above the 20th century average. This was the highest for January–October in the 1880–2015 record, surpassing the previous record set in 2014 by 0.22°F (0.12°C). Eight of the first ten months in 2015 have been record warm for their respective months."

—National Centers for Environmental Information

(I could go on and on and on. I won't, for all our sakes.)

After listening to Heather Love and Tavia Nyong'o at MSA, I came back to the idea I've been tossing around, inspired by Steve Shaviro's great book

No Speed Limit, of the value of aesthetics to at least stand outside neoliberalism. Love and Nyong'o seemed dismissive of aesthetics, and I wanted to mention

Commonwealth of Letters to them, and propose that perhaps if an art-for-art's-sake aesthetic is not, obviously, an instigator of utopian revolution, it may be a refuge. Kalliney shows that such an attention to aesthetics was just that for some colonial subjects in the 1930s who came to London to be writers and intellectuals. I am wary of an anti-aesthetic politics, a politics that seeks revolution but not the good life, a politics that does the work of neoliberalism by insisting on usefulness.

The university certainly has been an imperfect refuge, often just the opposite of refuge. Aesthetic attention will not open up a panacea or a utopia, nor will the refuge it provides be significantly more just and effective than the refuge of academia. But it is not nothing, and it is not anti-political. I think Marcus's writings demonstrate that. She recuperates

The Years and

Three Guineas not only by arguing for their political power, but for their aesthetic achievements. They survive, and we who cherish them are able to cherish them, not only because of what they say, but how they say it. Form matters. Form is matter.

Which is not to say, of course, that we should descend into a shallow formalism any more than we should wrap ourselves in the righteousness of an easy economism. Remember history. Remember nuance. Remember not to distort realities for the sake of an easy point. Don't provide cover for the exploiters and oppressors.

5. Art and Anger

Photographs of suffragettes lying bloody, hair dishevelled, hats askew, roused public anger toward the women, not their assailants. They were unladylike; they provoked the authorities. Demonstrations by students and blacks arouse similar responses. Thejustice of a cause is enhanced by the nonviolence of its adherents. But the response of the powerful when pressed for action has been such that only anger and violence have won change in the law or government policy. Similar contradictions and a double standard have characterized attitudes toward anger itself. While for the people, anger has been denounced as one of the seven deadly sins, divines and churchmen have always defended it as a necessary attribute of the leader. "Anger is one of the sinews of the soul" wrote Thomas Fuller, "he that wants it hath a maimed mind." "Anger has its proper use" declared Cardinal Manning, "Anger is the executive power of justice." Anger signifies strength in the strong, weakness in the weak. An angry mother is out of control; an angry father is exercising his authority. Our culture's ambivalence about anger reflects its defense of the status quo; the terrible swift sword is for fathers and kings, not daughters and subjects. The story of Judith and the story of Antigone have not been part of the education of daughters, as both Elizabeth Robins and Virginia Woolf point out, unless men have revised and rewritten them. It is hardly possible to read the poetry of Sappho, they both assure us, separate from centuries of scholarly calumny.

—Jane Marcus, "Art and Anger"

Why not create a new form of society founded on poverty and equality? Why not bring together people of all ages and both sexes and all shades of fame and obscurity so that they can talk, without mounting platforms or reading papers or wearing expensive clothes or eating expensive food? Would not such a society be worth, even as a form of education, all the papers on art and literature that have ever been read since the world began? Why not abolish prigs and prophets? Why not invent human intercourse? Why not try?

—Virginia Woolf, "Why?"

------------

*In

"Planetarity: Musing Modernist Studies", Susan Stanford Friedman sums up some of the changes that made the New Modernist Studies seem new: "Modernism, for many, became a reflection of and engagement with a wide spectrum of historical changes, including intensified and alienating urbanization; the cataclysms of world war and technological progress run amok; the rise and fall of European empires; changing gender, class, and race relations; and technological inventions that radically changed the nature of everyday life, work, mobility, and communication. Once modernity became the defining cause of aesthetic engagements with it, the door opened to thinking about the specific conditions of modernity for different genders, races, sexualities, nations, and so forth. Modernity became modernities, a pluralization that spawned a plurality of modernisms and the circulations among them.

By: Helena Palmer,

on 10/27/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Poetry,

Literature,

modernism,

ezra pound,

Spanish Literature,

federico garcia lorca,

Antonio Machado,

*Featured,

20th Century Literature,

spanish poetry,

Arts & Humanities,

european literature,

francoism,

Spanish Modernism,

spanish poets,

The Poetry of Antonio Machado,

Xon de Ros,

Add a tag

Comparison between the lives of Antonio Machado and Federico García Lorca is inevitable and not just because they are the two major Spanish poets of the twentieth century. They had met, and admired each other’s work. Both were victims of the Civil War.

The post Literary lottery? Antonio Machado’s reputation at home and abroad appeared first on OUPblog.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 6/7/2015

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

books,

reviews,

history,

Publishing,

Oxford University Press,

academia,

aesthetics,

Modernism,

Rhys,

postcolonialism,

colonialism,

Tutuola,

Add a tag

It is unfortunate that, so far as I can tell,

Oxford University Press has not yet released an affordable edition of Peter J. Kalliney's

Commonwealth of Letters, a fascinating book that is filled with ideas and information and yet also written in an engaging, not especially academic, style. It could find a relatively large audience for a book of its type and subject matter, and yet its publisher has limited it to a very specific market.

I start with this complaint not only because I would like to be able to buy a copy for my own use that does not cost more than $50, but because one of the many things Kalliney does well is trace the ways decisions by publishers affect how books, writers, and ideas are received and distributed. A publisher's decision about the appropriate audience for a book can be a self-fulfilling prophecy (or an unmitigated disaster). OUP has clearly decided that the audience for

Commonwealth of Letters is academic libraries and rich academics. That's unfortunate.

Modernism and postcolonialism have typically been seen (until recently) as separate endeavors, but Kalliney shows that, in the British context, at least, the overlap between modernist and (post)colonial writers was significant. Modernist literary institutions developed into postcolonial literary institutions, at least for a little while. (Kalliney shows also how this development was very specific to its time and places. After the early 1960s, things changed significantly, and by the early 1980s, the landscape was almost entirely different.) Of course, writers on the history of colonial and post-colonial publishing have traced the effects of various publishing decisions (book design, marketing, etc.) before, especially with regard to how late colonial and early postcolonial writers were sold in the mid-20th century. Scholars have toiled in archives for a few decades to dig out exactly how the

African Writers Series, for instance, distributed its wares. The great virtue of Kalliney's book is not that it does lots of new archival research (though there is some), but that it draws connections between other scholars' efforts, synthesizes a lot of previous scholarship, and interprets it all in often new and sometimes quite surprising ways.

Another of the virtues of the book is that though it has a central thesis, there is enough density of ideas that you could, I expect, reject the central thesis and still find value in a lot of what Kalliney presents. That primary argument is (to reduce it to its most basic form) that the high modernist insistence on aesthetic autonomy was both attractive and useful for late colonial and early postcolonial writers.

Undoubtedly, late colonial and early postcolonial writers attacked imperialism in both their creative and expository work. But this tendency to politicize their texts was complemented by the countervailing and even more potent demand to be recognized simply as artists, not as artists circumscribed by the pernicious logic of racial difference. the prospect of aesthetic autonomy — in particular, the idea that a work of art exists, and could circulate, without a specifically racialized character — would be used as a lever by late colonial and early postcolonial writers to challenge racial segregation in the fields of cultural production. (6)

Kalliney is able to develop this idea in a way that portrays colonial and postcolonial writers as thoughtful, complex people, not just dupes of the maybe-well-intentioned-but-probably-exploitive modernists. In Kalliney's portrait, writers such as Claude McKay and Ayi Kwei Armah demonstrate a sympathy for certain tenets of modernism (and its institutions) as well as the shrewdness to recognize what within modernist ideas was useful. Such shrewdness allowed them not only to get published and recognized, but also to reconfigure modernist methods for their own purposes and circumstances.