new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Ernest Hemingway, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 39

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Ernest Hemingway in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

The team at TrustEssays.com has created an infographic called “10 Weird Writing Habits of Famous Authors.” The piece features insights into the writing practices of Truman Capote, Ernest Hemingway, and Flannery O’ Connor.

We’ve embedded the full image below for you to explore further—what do you think? To learn more about some of your favorite writers, follow these links to view infographics on “The Day Jobs That Inspired Famous Authors,” “Writing Tips From Famous Authors,” and “Exploring the Careers of Famous Authors.” (via Lifehack)

The Morgan Library is hosting an exhibit called “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars.”

The Morgan Library is hosting an exhibit called “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars.”

Some of the items on display include early short stories, notebooks, manuscripts, pictures, and letters between the Nobel Prize-winning author and several beloved writers such as Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald. A closing date has been set for Jan, 31, 2016.

Here’s more information from The Morgan Library’s website: “This is the first ever major museum exhibition devoted to the work of Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), one of the most celebrated American authors of the 20th century…Focusing on the inter-war years, the exhibition explores the most consistently creative phase of Hemingway’s career and includes inscribed copies of his books, a rarely-seen 1929 oil portrait, photographs, and personal items.”

By Nick Cross

To the uninitiated, writing appears to be a simple process of putting words onto the page. But the fact that I’ve re-written the sentence you’ve just read six times seems to indicate that perhaps it’s not that easy. To write well requires us to make a deep personal connection with the material, and this is where the trouble starts.

Ernest Hemingway famously said:

“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

A trifle melodramatic, you might think, and just imagine the mess it caused to the internal workings of his typewriter! But we understand exactly what he meant. And there’s another use of the word “bleed” that is even more pertinent to the writing experience – the way that our daily experiences, ideas and emotions bleed into our work. Writing is not an activity that respects boundaries, in fact it actively thrives on recycling our happiest and saddest moments, tapping into our deepest fears and exposing our most shameful thoughts.

This might all be fine if the transfer was only one way. But the process of writing, editing and getting published generates a whole host of other emotions which can, in turn, affect our lives away from the desk. Often, we may not realise that we’re building a psychological house of cards, until the sudden, brutal event comes that causes it all to collapse. Life

happens.

For me, the trigger event was the simple failure of my novel to find a publisher (something I covered in detail in

my earlier Slushpile post). For others, it can be something far worse. In

Cliff McNish’s post from June this year, he talks movingly about the death of his wife and how he found himself unable to write the ghost story his publisher wanted:

“Day after day I wrote less and less until finally ... I just stopped. I didn’t want to be in this dark place. I had enough darkness going on in my life.”

Cliff, I’m pleased to say, found a way out of the darkness and is back to writing books again. And so am I, for that matter. But what is it that allows us to see past shattering events and gradually bring our lives back onto an even keel? Psychologists call this trait “resilience” and the American Psychological Association (APA) defines it as follows:

Resilience is the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress — such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems or workplace and financial stressors. It means "bouncing back" from difficult experiences.

Building resilience is a core skill for writers, but something that’s often overlooked. The APA have

an excellent factsheet about building resilience, and here (very briefly) are their 10 tips:

- Make connections

- Avoid seeing crises as insurmountable problems

- Accept that change is a part of living

- Move toward your goals

- Take decisive actions

- Look for opportunities for self-discovery

- Nurture a positive view of yourself

- Keep things in perspective

- Maintain a hopeful outlook

- Take care of yourself

The factsheet is very good, and I suggest you read it so I won’t have to regurgitate any more of the information here! Instead, I’d like to share some personal strategies that have worked for me, in the hope that they’ll prove useful.

Write what you want – not what you think you should

You may think you’re writing what you want to, but are you? External pressures such as market trends, agent feedback or peer pressure can subtly affect what projects you choose to pursue. And there’s also the element of “doing what you’ve always done.” We’ve seen that already in Cliff McNish’s piece, and I was struck by

another recent post by Sarah Aronson where she talks about changing writing direction to find peace of mind (and also success!)

Like Cliff and Sarah, I found that writing dark, difficult books worsened my mental condition, which in turn made my writing worse. So I decided to change direction and write lighter, funnier stuff instead. I wouldn’t say it’s been easier exactly (I still find writing pretty hard work), but it’s allowed me to tap into the positive, and make myself laugh into the bargain.

“What about the cathartic effect of writing?” I hear you say. Well, I agree that you can use writing as a form of therapy, and I think that’s why my short stories have been getting darker in the meantime (You can

read more about the process behind that). Short stories are perfect for me because the process is much, much shorter than writing a novel – I can get the darkness out of my brain and onto the page without wallowing in it.

|

| The darkest of my recent stories |

“Too much of anything can make you sick.”

I’d love to attribute that quote to a great philosopher, but in fact it’s the opening line of Cheryl Cole’s debut single

Fight for this Love! Nevertheless, the sentiment holds true, linking nicely into my previous point.

Doing everything in moderation is important to both mental and physical health. It’s tempting to lock yourself in a room for eight hours and burn through as many words as possible, but it’s not a healthy long term approach. Varying when, how and what you write can help you work around external pressures and will probably improve your creativity too.

Worry about Your Worrying

Writers are great worriers. This can be a positive trait, because it allows us to catastrophise, imagining all of the worst things that can go wrong in any situation and make sure they happen to our characters! But the same overactive mental process that allows us to plot stories can manifest in other situations as worry and rumination. Here’s a quick definition if the latter term is unfamiliar:

Rumination is the compulsively focused attention on the symptoms of one's distress, and on its possible causes and consequences, as opposed to its solutions.

Rumination is believed by psychology practitioners to be

a leading factor in depression and anxiety. It’s a big risk for people who are naturally introspective and spend a lot of time inside their own heads. Er, that’s us, people.

Cognitive Behavioural Treatment (CBT) is a common way of handling negative thought patterns. I’ve had a fair bit of CBT treatment over the past five years, but it’s only in the last six months that it’s really started to stick. Your mileage will doubtless vary, and there are other treatments that may work better for you instead. See the resources section at the end for more details.

Don’t be an emotional sponge

The world is full of awful events, which – while being horrible, immoral and upsetting – don’t tend to touch our lives directly. So we experience them at a distance via news and social media, sending out our empathy in place of direct experience. This is (once again) a double-edged sword, because the process which allows us to write convincing characters by stepping into their shoes, also allows us to be very quickly overwhelmed by other’s woes.

When I was at my lowest ebb, I can remember sitting on Twitter and feeling that I was being crushed by other people’s sadness – here was someone going through a divorce, or coping with sick kids, or lamenting a parent who died years ago. I had lost perspective of the positive posts, sucking up the painful and the negative emotions like a sponge.

The simple solution for me, was to take a break from Facebook and Twitter and BBC News, to insulate myself from the grief of the world until I was strong enough to face it again.

Beware the end-of-project blues

These are a big issue for me – after the wave of euphoria and relief that a big project has been completed, I will invariably sink into a period of low mood. The Friday before last, we delivered a brand new website at work, after an incredibly ambitious and stressful ten week schedule. As the first step in a projected ten year programme, the site was an unqualified success, and I had every reason to feel extremely proud of my contribution. But instead, I mooched around the house throughout the bank holiday weekend, feeling sorry for myself.

Writing projects are no different, and the stresses can be much worse because the completion of a final draft is invariably followed by submission to agents and editors, which creates its own anxieties. I know that other writers advise you to always have more than one book on the go, so that you can immediately switch to the other one. But I find I work best in intensive bursts, which doesn’t always suit that manner of working.

I remember reading about

fashion designer Alexander McQueen’s suicide, which was triggered, in part, by reaching the end of a fashion project. As McQueen’s psychiatrist told the inquest into his death:

“Usually after a show he felt a huge come-down. He felt isolated, it gave him a huge low.”

Try to plan for the end-of-project blues and have a strategy to cope with them – this may be as simple as allowing yourself not to feel guilty about the low that inevitably follows a high. Although your body and mind will need a rest after an intensive period of work, try to ramp down slowly and structure your downtime.

Build a Support Network

Everyone needs supportive friends and family to celebrate the good times and get them through the bad. Build and nurture your support network by finding like-minded people to share your journey (hello SCBWI!) If you have mental health problems and seek out a community of fellow sufferers, be vigilant to the difference between supportive friends and ones who can become a burden or project their own woes onto you (the emotional sponge problem).

Additional Resources

Living Life to the Full

This is a

free self-help website set up by a Scottish psychiatrist and partly-funded by the NHS. It offers a range of online CBT courses and factsheets to address problems such as anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and addiction.

NHS Choices

This site has lots of

mental health advice, including the

Moodzone which focuses on stress, anxiety and depression.

Manage Your Mind

This

bestselling book by Gillian Butler and Tony Hope is a very approachable and comprehensive guide to mental fitness. At 500 pages, its size can be a little off-putting, and I was scared of reading it for years! But once I finally opened it, I found it both comforting and useful. (full disclosure – my employer publishes this book, but that’s also one of the reasons it’s so good!)

Therapy and Counselling

There are lots of websites and directories of therapists/counsellors, and the choice can be confusing as there are many different types of therapy available. Always look for someone with accreditation – the more reputable sites will show you this information (for instance,

It’s Good to Talk is a directory of practitioners who are accredited by The British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy). Always “try before you buy” - the practitioner-patient relationship needs to work in both directions to be effective, and good therapists will offer you a free trial session before you commit to regular meetings.

As well as private therapy, I have had counselling on the NHS in the past, although mental health services have been hit very hard by recent government spending cuts and you may struggle to get a referral unless your condition is serious.

Life Coaching

Life coaching is not an alternative to psychotherapy but more of a complement – it won’t help you with deep-seated psychological conditions, but is useful for addressing issues such as confidence, motivation and reaching your career goals. I’ve recently had a course of sessions with a life coach and found it immensely helpful (if pretty expensive). In fact, the confidence it’s given me is pretty much the reason I’m writing this blog post.

Although she wasn’t my life coach, I’d like to give a shout out here to the lovely Bekki Hill, who runs a website called

The Creativity Cauldron and specialises in coaching writers through their creative troubles.

OK, I think that’s quite enough from me! I hope you’ve found this post both useful and enjoyable. The issue of mental health for creative people is one that doesn’t get enough focus, so I hope I’ve redressed the balance a little.

Stay resilient,

Nick.

Nick Cross is a children's writer, Undiscovered Voices winner and Blog Network Editor for

SCBWI Words & Pictures Magazine.

Nick's writing is published in

Stew Magazine, and he's recently received the

SCBWI Magazine Merit Award, for his short story

The Last Typewriter.

In the past, A.J. Jacobs revealed that he has several famous \"cousins\" including former President George H. W. Bush, filmmaker Morgan Spurlock, and Harry Potter movie series actor Daniel Radcliffe.

In the past, A.J. Jacobs revealed that he has several famous \"cousins\" including former President George H. W. Bush, filmmaker Morgan Spurlock, and Harry Potter movie series actor Daniel Radcliffe.

Over the weekend, Jacobs hosted the Global Family Reunion in New York City. The journalist shared an extended family tree which unveiled his connection to several notable authors.

According to Jacobs’ research, he is cousin to the following writers: English playwright William Shakespeare, Green Eggs and Ham creator Dr. Seuss, comics legend Stan Lee, horror master Stephen King, and Nobel Prize winner Ernest Hemingway. Click here to watch a TED talk about the origins of this genealogy project.

Lionsgate has picked up the U.S. rights to the Genius biopic. The story for this movie comes from A. Scott Berg’s nonfiction book, Max Perkins: Editor of a Genius.

Lionsgate has picked up the U.S. rights to the Genius biopic. The story for this movie comes from A. Scott Berg’s nonfiction book, Max Perkins: Editor of a Genius.

Deadline.com reports that Michael Grandage, a filmmaker, took the helm as the director. John Logan, the scribe behind Gladiator and Hugo, served as the screenwriter.

Colin Firth, an Academy Award-winning actor, played the role of the legendary publishing icon. Throughout his career, Perkins worked with several famous authors including Thomas Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. (via The Hollywood Reporter)

By: Powell's Staff,

on 3/20/2015

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

Travel Writing,

Woody Guthrie,

Required Reading,

Ernest Hemingway,

jack kerouac,

Tony Hillerman,

Jon Krakauer,

Jean-claude Izzo,

Jeff Johnson,

Keri Hulme,

Add a tag

Ahead of a trip, many of us gravitate toward books that depict the history and culture of our travel destination. But it can work the other way around, too. Sometimes a book provides such a powerful sense of place that we find ourselves longing to visit the area we read about. Some of us even [...]

I read this book during my senior year of college to take a break from my business reading requirements. It inspired me to buy a plane ticket to Spain as a graduation present to myself. I went and ran with the bulls in Pamplona and felt like I was living out a story. I will [...]

Did you know that Truman Capote had a sharp tongue? The team at AussieWriter.com has created an infographic that shine the spotlight on “Famous Writers’ Insults.”

Did you know that Truman Capote had a sharp tongue? The team at AussieWriter.com has created an infographic that shine the spotlight on “Famous Writers’ Insults.”

The image features quotes from The Invisible Man author H. G. Wells, Madame Bovary author Gustave Flaubert, and The Sun Also Rises author Ernest Hemingway. We’ve embedded the full infographic below for you to explore further—what do you think? (via The Digital Reader)

Have you ever wanted to ask for advice from a great author? The team at BestEssayTips.com has created an infographic with “Timeless Original Writing Techniques of Famous Writers.”

Have you ever wanted to ask for advice from a great author? The team at BestEssayTips.com has created an infographic with “Timeless Original Writing Techniques of Famous Writers.”

The image features tips from The Shining author Stephen King, The Old Man And The Sea author Ernest Hemingway, and A Wrinkle in Time author Madeleine L’Engle. We’ve embedded the full infographic below for you to explore further—what do you think?

Scribner, an imprint at Simon & Schuster, has launched a new digital publication called Scribner Magazine.

Scribner, an imprint at Simon & Schuster, has launched a new digital publication called Scribner Magazine.

Here’s more from the press release: “Inspired by the publisher’s celebrated sister publication Scribner’s Magazine (1887-1939), but reimagined for the 21st century reader, Scribner Magazine will feature original writing and interactive media, along with written and audio book excerpts, photo galleries, author-curated music playlists, bookseller reviews, and articles that offer a glimpse inside the world of publishing. Scribner Magazine also integrates Scribner’s popular Twitter feed, and the site highlights current Scribner book news and author events, so consumers can stay informed about their favorite writers.”

The first issue features a diverse range of content such as rare photographs from the publication of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises: The Hemingway Library Edition, an audio recording of the “Something That Needs Nothing” short story written and read by Miranda July, and pieces from several high profile contributors. Novelist Anthony Doerr wrote an essay about the writing process for All The Light We Cannot See, actor James Franco reveals how he became a writer in an essay, and Betsy Burton, a bookseller from The King’s English Bookshop, penned a review of Nora Webster by Colm Tóibín.

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Shakespeare and Company has been profiled in an Oprah’s Super Soul Sunday short film. We’ve embedded the entire piece in the video above—what do you think? Past patrons of the famous Parisian independent bookstore include Ezra Pound, Ernest Hemingway, and James Joyce.

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Ninja Essays has created an infographic called, “Unusual Work Habits of Writers,” which focuses on the unconventional writing practices employed by famous authors.

Ninja Essays has created an infographic called, “Unusual Work Habits of Writers,” which focuses on the unconventional writing practices employed by famous authors.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer author Mark Twain preferred to write while lying down. Conversely, The Old Man & The Sea author Ernest Hemingway favored standing up.

We’ve embedded the entire graphic below for you to explore further. Do you have any unusual work habits?

(more…)

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Tom Rachman,

on 6/2/2014

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Tom Rachman,

Original Essays,

Charles Dickens.,

Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy,

Paul Kennedy,

Literature,

George Orwell,

William Shakespeare,

john steinbeck,

F. Scott Fitzgerald,

Evelyn Waugh,

Ernest Hemingway,

Harper Lee,

Gustave Flaubert,

Add a tag

Naming a novel is painstaking, agonizing, delicate. But does the title matter? It certainly feels consequential to the author. After several years' battle with your laptop keyboard, after 100,000 words placed so deliberately, you must distill everything into a phrase brief enough to run down the spine of a book. Should it be descriptive? Perhaps [...]

Simon & Schuster has established a partnership with Scribd and Oyster.

Readers will now have access to the publisher's backlist eBook titles. Some of the books now available through these two eBook subscription services include 11/22/63 by Stephen King, The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult, In Her Shoes by Jennifer Weiner, and How to be Compassionate by The Dalai Lama.

CEO Carolyn Reidy had this statement in the press release: "Consumers have clearly taken to subscription models for other media, and we expect that our participation in these services will encourage discovery of our books, grow the audience and expand our retail reach for our authors, and create new revenue streams under an author-friendly, advantageous business model for both author and publisher. We are delighted to work with Scribd and Oyster to offer this exciting new model for readers to find and read eBooks, and to do so in a manner that respects the value of our authors’ creative endeavors and supports our mutual goals of selling the most possible copies of their books."

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

In October 1925, a young writer named Ernest Hemingway wrote a letter to a younger Canadian author named Morley Callaghan.

In October 1925, a young writer named Ernest Hemingway wrote a letter to a younger Canadian author named Morley Callaghan.

Callaghan was frustrated with his writing life and wrote to his friend: “Have a lot of time and could go a good deal of writing if I knew how I stood.”

Hemingway’s response is included in volume two of The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, out this month. We’ve quoted his response below, great advice for writers of any age…

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

I finished reading The Paris Wife recently for my prison book club. The Paris Wife is the story of Hemingway’s first wife, Hadley, and her experience as his spouse while living as a member of The Lost Generation in Paris. The book was excellent: beautifully written, honest, and terribly tragic (as we all know how their relationship ends …). Because of The Paris Wife, I decided it was time to revisit Ernest Hemingway. And God help me.

I decided to pick up The Sun Also Rises, because the bull fight scenes in Pamplona were a huge part of The Paris Wife. I knew, thanks to Hadley’s first person account, that The Sun Also Rises is very true, featuring people who actually existed, who were “friends” of the Hemingway’s. I use the term “friends” loosely because honestly I’m not sure how much any of these people liked each other, which is made even more apparent in The Sun Also Rises.

I decided to pick up The Sun Also Rises, because the bull fight scenes in Pamplona were a huge part of The Paris Wife. I knew, thanks to Hadley’s first person account, that The Sun Also Rises is very true, featuring people who actually existed, who were “friends” of the Hemingway’s. I use the term “friends” loosely because honestly I’m not sure how much any of these people liked each other, which is made even more apparent in The Sun Also Rises.

A small novel, Sun took me way longer than it should have to complete. Not because the diction was difficult; obviously not—we’re talking about Hemingway, a master of using very few words to get across huge thematic points. No, Sun took me a long time to read because I was bored.

Granted, I want to give Hemingway his due. He is a genius with dialogue. He says so much by saying nothing at all. Most of the time, everything is subtext, but it’s brilliant! Brilliant! So dialogue: points! Many points. He understands human nature and is capable of creating an entire, fully realized character with nothing but his or her words. That is not easy.

Yet, I find his work to be boring. I can’t put my finger on it. I suppose, in the case of The Sun Also Rises, the repetition of “another bottle of wine” and “I’m tight” got a little old. They’re all drunk the entire book, which is why the ugliness comes out—why friends leave Pamplona as enemies.

Maybe his descriptions. I don’t like his descriptions. They’re not flowery enough for me. My favorite authors are European—Spanish mostly—and those romance language dudes know how to speak pretty. Hemingway? Not so much, which is part of his fame, part of his allure. Yet, this stagnant use of language was not alluring to me. BORED!

Maybe his descriptions. I don’t like his descriptions. They’re not flowery enough for me. My favorite authors are European—Spanish mostly—and those romance language dudes know how to speak pretty. Hemingway? Not so much, which is part of his fame, part of his allure. Yet, this stagnant use of language was not alluring to me. BORED!

I have another theory: do you think Hemingway wrote for a male audience? Do you suppose, as a female, I just don’t relate? I mean, he was a Man’s Man. He was a a fighter, a drunk, a womanizer. Maybe if I had a set of balls, his work would resonate better, because as a woman, I find his female characters to be quite despicable—and maybe that’s what he intended. No matter how much he loved women in his life, he had a way of tossing them away when the next best thing came around. Perhaps he fits this philosophy into his work.

In conclusion, I gave Hemingway another shot. Did I enjoy myself? Eh. At times. There were brilliant lines: “I have a rotten habit of picturing the bedroom scenes of my friends.” Or: “I was a little drunk. Not drunk in any positive sense but just enough to be careless.” Another: “Cohn had a wonderful quality of bringing out the worst in anybody.” My God, brilliant!!

That said I won’t be going back to good old Ernest. I still have flashbacks of the horror of The Old Man and the Sea from high school, and although The Sun Also Rises was better, I’m still not interested in tackling his body of work. Thanks, Ernest, for being you and for creating a new style of American writing. However, we’re breaking up. It’s not you; it’s me.

ParchedMelanie Crowder

Middle Grade

Summer has come and gone so quickly, fortunately packed with a lot of amazing reads. Which made choosing this first Fall review hard! I decided to go with my fellow Vermont College friend and amazing writer, Melanie Crowder's first book,

Parched. You might argue that I'll be slightly biased in my review of this work, but this story, from its inklings to final version, won a few prestigious VCFA awards, landed Melanie her agent and first book contract. It doesn't need my bias. It stands... shines... all on its own.

Very succinctly, the story chronicles the struggles of a girl surviving on the parched African savanna and a boy escaping a d(r)ying city in search of water.

In only 160 pages, Crowder develops characters and situations so powerful they have followed me throughout all of my other reads. It's a little bit magical how she does this. It's as if she discovered Hemingway's secret for parsimony. The writing is sparse but fully packed. In some ways, it's as if poetic style has been applied to prose. For that reason alone, if you're looking for tricks of the trade, Crowder's work will keep you up nights deconstructing to figure out just how she does it.

POV is used extremely deftly. Whenever the story follows either child, POV is omniscient/close 3rd. However, this is interspersed with an unusual 1st person perspective from the POV of the main hunting dog. These short chapters are like a raw, direct, honest emotional punch that jolts the reader and pulls them deeper into story.

Finally, this story itself works like a dip into the pool of all the story that is going on around the characters. Crowder shows only what needs showing, while nevertheless belying a sense of extreme depth to her characters.

Spoiler Alert: Dogs do get hurt in this book. Yes, it is another dead dog book. My kids may never forgive me for buying it for them and urging them to read it. Protest signs against parental evilness line the walls of our house. I can think of no greater compliment for Crowder. She pulled them in. She made them care. She made them mourn and KEEP READING.

Move over

Where the Red Fern Grows. There is a new contender for greatness.

For more great reads, stroll over to

Barrie Summy's site. She's serving them up cool and refreshing!

By: Alice,

on 2/26/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

classic,

joyce,

William Carlos Williams,

OWC,

modernism,

Tom Stoppard,

henry james,

Oxford World's Classics,

Gertrude Stein,

Robert Lowell,

ezra pound,

Ernest Hemingway,

first world war,

Joseph Conrad,

Humanities,

Jean Rhys,

Theodore Dreiser,

Benedict Cumberbatch,

*Featured,

Stephen Crane,

TV & Film,

Susanna White,

Arts & Leisure,

e. e. cummings,

Ford Madox Ford,

Good Soldier,

Max Saunders,

Parade’s End,

A Dual Life,

British novel,

Christopher Tietjens,

D. H. Lawrence,

Rebecca Hall,

Stella Bowen,

Valentine Wannop,

Wyndham Lewis,

Add a tag

By Max Saunders

One definition of a classic book is a work which inspires repeated metamorphoses. Romeo and Juliet, Gulliver’s Travels, Frankenstein, Dracula, The Great Gatsby don’t just wait in their original forms to be watched or read, but continually migrate from one medium to another: painting, opera, melodrama, dramatization, film, comic-strip. New technologies inspire further reincarnations. Sometimes it’s a matter of transferring a version from one medium to another — audio recordings to digital files, say. More often, different technologies and different markets encourage new realisations: Hitchcock’s Psycho re-shot in colour; French or German films remade for American audiences; widescreen or 3D remakes of classic movies or stories.

Cinema is notoriously hungry for adaptations of literary works. The adaptation that’s been preoccupying me lately is the BBC/HBO version of Parade’s End, the series of four novels about the Edwardian era and the First World War, written by Ford Madox Ford. Ford was British, but an unusually cosmopolitan and bohemian kind of Brit. His father was a German émigré, a musicologist who ended up as music critic for the London Times. His mother was an artist, the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. Ford was educated trilingually, in French and German as well as English. When he was introduced to Joseph Conrad at the turn of the century, they decided to collaborate on a novel, and went on over a decade to produce three collaborative books. He also got to know Henry James and Stephen Crane at this time — the two Americans were also living nearby, on the Southeast coast of England. Americans were to prove increasingly important in Ford’s life. He moved to London in 1907, and soon set up the literary magazine that helped define pre-war modernism: the English Review. He had a gift for discovering new talent, and was soon publishing D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis alongside James and Conrad. But it was Ezra Pound, who he also met and published at this time, who was to become his most important literary friend after Conrad.

Cinema is notoriously hungry for adaptations of literary works. The adaptation that’s been preoccupying me lately is the BBC/HBO version of Parade’s End, the series of four novels about the Edwardian era and the First World War, written by Ford Madox Ford. Ford was British, but an unusually cosmopolitan and bohemian kind of Brit. His father was a German émigré, a musicologist who ended up as music critic for the London Times. His mother was an artist, the daughter of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown. Ford was educated trilingually, in French and German as well as English. When he was introduced to Joseph Conrad at the turn of the century, they decided to collaborate on a novel, and went on over a decade to produce three collaborative books. He also got to know Henry James and Stephen Crane at this time — the two Americans were also living nearby, on the Southeast coast of England. Americans were to prove increasingly important in Ford’s life. He moved to London in 1907, and soon set up the literary magazine that helped define pre-war modernism: the English Review. He had a gift for discovering new talent, and was soon publishing D. H. Lawrence and Wyndham Lewis alongside James and Conrad. But it was Ezra Pound, who he also met and published at this time, who was to become his most important literary friend after Conrad.

Ford served in the First World War, getting injured and suffering from shell shock in the Battle of the Somme. He moved to France after the war, where he soon joined forces with Pound again, to form another influential modernist magazine, the transatlantic review, which published Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Jean Rhys. Ford took on another young American, Ernest Hemingway, as his sub-editor. Ford held regular soirees, either in a working class dance-hall with a bar that he’d commandeered, or in the studio he lived in with his partner, the Australian painter Stella Bowen. He found himself at the centre of the (largely American) expatriate artist community in the Paris of the 20s. And it was there, and in Provence in the winters, and partly in New York, that he wrote the four novels of Parade’s End, that made him a celebrity in the US. He spent an increasing amount of time in the US through the 20s and 30s, based on Fifth Avenue in New York, becoming a writer in residence in the small liberal arts Olivet College in Michigan, spending time with writer-friends like Theodore Dreiser and William Carlos Williams, and among the younger generation, Robert Lowell and e. e. cummings.

Parade’s End (1924-28) has been dramatized for TV by Sir Tom Stoppard. It has to be one of the most challenging books to film; but Stoppard has the theatrical ingenuity, and experience, to bring it off. It’s a classic work of Modernism: with a non-linear time-scheme that can jump around in disconcerting ways; dense experimental writing that plays with styles and techniques. Though it includes some of the most brilliant conversations in the British novel, and its characters have a strong dramatic presence, much of it is inherently un-dramatic and, you might have thought, unfilmable: long interior monologues, descriptions of what characters see and feel; and — perhaps hardest of all to convey in drama — moments when they don’t say what they feel, or do what we might expect of them. Imagine T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’, populated by Chekhovian characters, but set on the Western Front.

I’ve worked on Ford for some years, yet still find him engaging, tantalising, often incomprehensibly rewarding, so I was watching Parade’s End with fascination. [Warning: Spoilers ahead.]

Click here to view the embedded video.

Stoppard and the director, Susanna White, have done an extraordinary job in transforming this rich and complex text into a dramatic line that is at once lucid and moving. Sometimes where Ford just mentions an event in passing, the adaptation dramatizes the scene for us. The protagonist is Christopher Tietjens, a man of high-Tory principle — a paradoxical mix of extreme formality and unconventional intelligence – is played outstandingly by Benedict Cumberbatch, with a rare gift to convey thought behind Tietjens’ taciturn exterior. In the novel’s backstory, Christopher has been seduced in a railway carriage by Sylvia, who thinks she’s pregnant by another man. The TV version adds a conversation as they meet in the train; then cuts rapidly to a sex scene. It’s more than just a hook for viewers unconcerned about textual fidelity, though. What it establishes is what Ford only hints at through the novel, and what would be missed without Tietjen’s brooding thoughts about Sylvia: that her outrageousness turns him on as much as it torments him. In another example, where the novelist can describe the gossip circulating like wildfire in this select upper-class social world, the dramatist needs to give it a location; so Stoppard invents a scene at an Eton cricket match for several of the characters to meet, and insult Valentine Wannop, while she and Tietjens are trying not to have the affair that everyone assumes they are already having. Valentine is an ardent suffragette. In the novel, she and Tietjens argue about women and politics and education. Stoppard introduces a real historical event from the period — a Suffragette slashing Velasquez’s ‘Rokeby Venus’ in the National Gallery — as a way of saying it visually; and then complicating it beautifully with another intensely visual interpolated moment. In the book Ford has Valentine unconcsciously rearranging the cushions on her sofa as she waits to see Tietjens the evening before he’s posted back to the war. When she becomes aware that she’s fiddling with the cushions because she’s anticipating a love-scene with him, the adaptation disconcertingly places Valentine nude on her sofa in the same position as the ‘Rokeby Venus’ — in a flash both sexualizing her politics and politicizing her sexuality.

Such changes cause a double-take in viewers who know the novels. But they’re never gratuitous, and always respond to something genuine in the writing.

Perhaps the most striking transformation comes during one of the most amazing moments in the second volume, No More Parades. Tietjens is back in France, stationed at a Base Camp in Rouen, struggling against the military bureaucracy to get drafts of troops ready to be sent to the Front Line. Sylvia, who can’t help loving Tietjens though he drives her mad, has somehow managed to get across the Channel and pursue him to his Regiment. She has been unfaithful, and he is determined not to sleep with her; but because his principles won’t let a man divorce a woman, he feels obliged to share her hotel room so as not to humiliate her publicly. She is determined to seduce him once more; but has been flirting with other officers in the hotel, two of whom also end up in their bedroom in a drunken brawl. It’s an extraordinary moment of frustration, hysteria, terror (there has been a bombardment that evening), confusion, and farce. In the book we sense Sylvia’s seductive power, and that Tietjens isn’t immune to it, even though by then in love with Valentine. He resists. But in the film version, they kiss passionately before being interrupted.

Valentine and Christopher. Adelaide Clemens and Benedict Cumberbatch in Parade’s End. (c) BBC/HBO.

The scene may have been changed to emphasize the power she still has over Tietjens: as if, paradoxically, he needs to be seen to succumb for a moment to make his resistance to her the more heroic. The change that’s going to exercise enthusiasts of the novels, though, is the way three of the five episodes were devoted to the first novel, Some Do Not…; and roughly one each to the second and third; with very little of the fourth volume, Last Post, being included at all. The third volume, A Man Could Stand Up — ends where the adaptation does, with Christopher and Valentine finally being united on Armistice night, a suitably dramatic and symbolic as well as romantic climax. Last Post is set in the 1920s and deals with post-war reconstruction. One can see why it would have been the hardest to film: much of it is interior monologue, and though Tietjens is often the subject of it he is absent for most of the book. Some crucial scenes from the action of the earlier books is only supplied as characters remember them in Last Post, such as when Syliva turns up after the Armistice night party lying to Christopher and Valentine that she has cancer in an attempt to frustrate their union. Stoppard incorporates this into the last episode, but he writes new dialogue for it to give it a kind of closure the novels studiedly resist. Valentine challenges her as a liar, and from Tietjens’ reaction, Sylvia appears to recognize the reality of his love for her and gives her their blessing.

Rebecca Hall, playing Sylvia, has been so brilliantly and scathingly sarcastic all the way through that this change of heart — moving though it is — might seem out of character: even the character the film gives her, which is arguably more sympathetic than the one most readers find in the novel. Yet her reversal is in Last Post. But what triggers it there, much later on, is when she confronts Valentine but finds her pregnant. Even the genius of Tom Stoppard couldn’t make that happen before Valentine and Christopher have been able to make love. But there are two other factors, which he was able to shift from the post-war time of Last Post into the war’s endgame of the last episode. One is that Sylvia has focused her plotting on a new object. Refusing the role of the abandoned wife of Tietjens, she has now set her sights on General Campion, and begun scheming to get him made Viceroy of India. The other is that she feels she has already dealt Tietjens a devastating blow, in getting the ‘Great Tree’ at his ancestral stately home of Groby cut down. In the book she does this after the war by encouraging the American who’s leasing it to get it felled. In the film she’s done it before the Armistice; she’s at Groby; Tietjens visits there; has a Stoppard scene with Sylvia arranged in her bed like a Pre-Raphaelite vision in a last attempt to re-seduce him, which fails partly because of his anger over the tree. In the books the Great Tree represents the Tietjens family, continuity, even history itself. Ford writes a sentence about how the villagers “would ask permission to hang rags and things from the boughs,” but Stoppard and White make that image of the tree, all decorated with trinkets and charms, a much more prominent motif, returning to it throughout the series, and turning it into a symbol of superstition and magic. But then Stoppard characteristically plays on the motif, and has Christopher take a couple of blocks of wood from the felled tree back to London. One he gives to his brother, in a wonderfully tangible and taciturn gesture of renouncing the whole estate and the history it stands for. The other he uses in his flat, throwing whisky over it in the fireplace to light a fire to keep himself and Valentine warm. That gesture shows how it isn’t just Sylvia who is saying ‘Goodbye to All That’, but all the major characters are anticipating the life that, though the series doesn’t show it, Ford presents in the beautifully elegiac Last Post.

Max Saunders is author of Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life (OUP, 1996/2012), and editor of Some Do Not . . ., the first volume of Ford’s Parade’s End (Manchester: Carcanet, 2010) and Ford’s The Good Soldier (Oxford: OUP, 2012). He was interviewed by Alan Yentob for the Culture Show’s ‘Who on Earth was Ford Madox Ford’ (BBC 2; 1 September 2012), and his blog on Ford’s life and work can be read on the OUPblog and New Statesman.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Portrait of Ford Madox Ford (Source: Wikimedia Commons); (2) Still from BBC2 adaption of Parade’s End. (Source: bbc.co.uk).

The post Ford Madox Ford and unfilmable Modernism appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Will Schwalbe,

on 10/2/2012

Blog:

PowellsBooks.BLOG

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Crime,

john steinbeck,

F. Scott Fitzgerald,

Christopher Isherwood,

US History,

Ernest Hemingway,

Guests,

Hilary Mantel,

Patricia Highsmith,

Monique Truong,

Patrick Suskind,

Amanda Vaill,

Barnet Schecter,

Chandler Burr,

Esther Forbes,

Kevin Baker,

Paul Hendrickson,

Simon Baatz,

Will Schwalbe,

Literature,

Biography,

Add a tag

I'm a big believer that books, like people, can have partners: there are pairs of books that complement each other and belong together. With some books, as soon as you mention one, someone is bound to mention the other. Obviously, this applies to sequels and prequels. If you say you like Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall, [...]

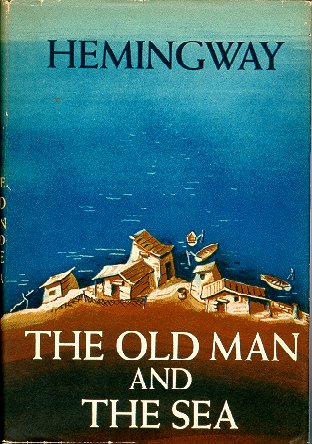

AbeBooks has released a list of the most expensive books it sold last month, a list that includes a $18,500 first edition of Ernest Hemingway‘s The Old Man and the Sea–signed “with very best wishes” by the novelist himself.

AbeBooks has released a list of the most expensive books it sold last month, a list that includes a $18,500 first edition of Ernest Hemingway‘s The Old Man and the Sea–signed “with very best wishes” by the novelist himself.

The month also included a $19,314 sale of a handwritten Latin bible from the 13th century, a $9,500 sale of 1930 edition of The Savoy Cocktail Book by Harry Craddock and a $9,000 first edition of The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton.

Here’s more about the most expensive book of the month: “Mystere de la Vengeance de Notre Seigneur by Eustache Mercade – $20,000 Published in 1491 in Paris by Antoine Verard, this first edition lacks 16 leaves, but only one complete copy is known to exist, in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. The sale also included a letter by French bibliographer Amedee Boinet, who confirms the exceptional rarity of this book.”

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Alice,

on 9/6/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Ford Madox Ford,

Good Soldier,

Max Saunders,

Parade’s End,

Literature,

modernism,

henry james,

Ernest Hemingway,

Impressionism,

first world war,

Graham Greene,

Humanities,

Jean Rhys,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Max Saunders

This year’s television adaptation of Parade’s End has led to an extraordinary surge of interest in Ford Madox Ford. The ingenious adaptation by Sir Tom Stoppard; the stellar cast, including Benedict Cumberbatch, Rebecca Hall, Alan Howard, Rupert Everett, Miranda Richardson, Roger Allam; the flawlessly intelligent direction by award-winning Susanna White, have not only created a critical success, but reached Ford’s widest audience for perhaps fifty years. BBC2 drama doubled its share of the viewing figures. Reviewers have repeatedly described Parade’s End as a masterpiece and Ford as a neglected Modernist master. Those involved in the production found him a ‘revelation’, and White and Hall are reported as saying that they were embarrassed that their Oxbridge educations had left them unaware of Ford’s work. After this autumn, fewer people interested in literature and modernism and the First World War are likely to ask the question posed by the title of Alan Yentob’s ‘Culture Show’ investigation into Ford’s life and work on September 1st: “Who on Earth was Ford Madox Ford?”

Sylvia and Christopher Tietjens, played by Rebecca Hall and Benedict Cumberbatch in the BBC2 adaptation of Parade's End.

It’s a good question, though. Ford has to be one of the most mercurial, protean figures in literary history, capable of producing violent reactions of love, admiration, ridicule or anger in those who knew him, and also in those who read him. Many of those who knew him were themselves writers — often writers he’d helped, which made some (like Graham Greene) grateful, and others (like Hemingway) resentful, and some (like Jean Rhys) both. So they all felt the need to write about him — whether in their memoirs, or by including Fordian characters in their fiction. Ford himself thought that Henry James had based a character on him when young (Merton Densher in The Wings of the Dove). Joseph Conrad too, who collaborated with Ford for a decade, is thought to have based several characters and traits on him.

I’d spent several years trying to work out an answer that satisfied me to the question of who on earth Ford was. The earlier, fairly factual biographies by Douglas Goldring and Frank MacShane had been supplanted by more psycho-analytic studies by Arthur Mizener and Thomas C. Moser. Mizener took the subtitle of Ford’s best-known novel, The Good Soldier, as the title of his biography: The Saddest Story. He presented Ford as a damaged psyche whose fiction-writing stemmed from a sad inability to face the realities of his own nature. Of course all fiction has an autobiographical dimension. A novelist’s best way of understanding characters is to look into his or her own self. But there is an element of absurdity in diagnosing an author’s obtuseness from the problems of fictional characters. This is because if writers can make us see what’s wrong with their characters, that means they understand not only those characters, but themselves (or at least the traits they share with those characters). John Dowell, the narrator of The Good Soldier, appears at times hopelessly inept at understanding his predicament. His friend, the good soldier of the title, Edward Ashburnham, is a hopeless philanderer. If Ford saw elements of himself in both types, he had to be more knowing than them in order to show them to us. And anyway, they’re diametrically opposed as types.

Ford’s psychology needs to be approached from a different angle. Rather than seeing his fiction as displaying symptoms that give him away, what if it is diagnostic? What if, rather than projecting wishful fabrications of himself, he turns the spotlight on that process of fabrication itself — on the processes of fantasy that are inseparable from our subjectivities? To answer the question of who Ford was, we have to look at the ways his work explores how we understand ourselves through stories: the stories that are told to us, the stories we tell ourselves; the myths and histories and anecdotes that populate our imaginations. Where Moser had concentrated on what he called The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford — trying to identify biographical markers in episodes in novels — I found myself in quest of ‘the fiction in the life’.

Ford’s psychology needs to be approached from a different angle. Rather than seeing his fiction as displaying symptoms that give him away, what if it is diagnostic? What if, rather than projecting wishful fabrications of himself, he turns the spotlight on that process of fabrication itself — on the processes of fantasy that are inseparable from our subjectivities? To answer the question of who Ford was, we have to look at the ways his work explores how we understand ourselves through stories: the stories that are told to us, the stories we tell ourselves; the myths and histories and anecdotes that populate our imaginations. Where Moser had concentrated on what he called The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford — trying to identify biographical markers in episodes in novels — I found myself in quest of ‘the fiction in the life’.

Compared to some of the canonical modernists like Joyce or Eliot, Ford is unusual in writing so much about his own life — a whole series of books of reminiscences. They’re full of marvelous stories. Take the one with which he ends his book celebrating Provence. He describes how, when he earned a sum of money during the Depression, he and Janice Biala decided it was safer to cash it all rather than trust to failing banks. They visit one of Ford’s favourite towns, Tarascon on the Rhone. Ford has entrusted the banknotes to Biala. “I am constitutionally incapable of not losing money,” said Ford. But as they cross the bridge, the legendary mistral starts blowing:

And leaning back on the wind as if on an upended couch I clutched my béret and roared with laughter… We were just under the great wall that keeps out the intolerably swift Rhone… Our treasurer’s cap was flying in the air… Over, into the Rhone… What glorious fun… The mistral sure is the wine of life… Our treasurer’s wallet was flying from under an armpit beyond reach of a clutching hand… Incredible humour; unparalleled buffoonery of a wind… The air was full of little, capricious squares, floating black against the light over the river… Like a swarm of bees: thick… Good fellows, bees….

And then began a delirious, panicked search… For notes, for passports, for first citizenship papers that were halfway to Marseilles before it ended… An endless search… With still the feeling that one was rich… Very rich.

“I hadn’t been going to do any writing for a year,” mused Ford, recognising what an unlikely prospect it was. “But perhaps the remorseless Destiny of Provence desires thus to afflict the world with my books….” Yet for all the wry cynicism of this afterthought Biala remembered that “Ford was amused for months at the thought that some astonished housewife cleaning fish might have found a thousand-franc note in its belly.”

Ford’s stories, for all their playfulness, also earned him notoriety for the liberties they took with the facts. Indeed, Ford courted such controversy, writing in the preface to the first of them, Ancient Lights, in 1911:

This book, in short, is full of inaccuracies as to facts, but its accuracy as to impressions is absolute [....] I don’t really deal in facts, I have for facts a most profound contempt. I try to give you what I see to be the spirit of an age, of a town, of a movement. This can not be done with facts. (pp. xv-xvi)

He called his method Impressionism: an attention to what happens to the mind when it perceives the world. Ford is the most important analyst in English of Impressionism in literature, not only elaborating the techniques involved, but defining a movement. This included writers he admired like Flaubert, Maupassant and Turgenev, as well as his friends James, Conrad, and Crane. He also used the term to cover writers we now think of as Modernist, such as Rhys, Hemingway, or Joyce. Though most of these writers were resistant to the label, they wrote much about ‘impressions’ and their aesthetic aims have strong family resemblances.

One feature that sets Ford’s writing apart is his tendency to retell the same stories, but with continual variations. This creates an immediate problem for a literary biographer wanting to use the subject’s autobiographical writing to structure the narrative upon. Which version to use? Which to believe? They can’t all be true. And their sheer proliferation and multiplicity shows how he couldn’t tell a story about himself without it turning into a kind of fiction. In one particularly striking example, which Ford tells at least five times, he is taking the train with Conrad to London to take to their publisher corrected proofs of their major collaborative novel, Romance. Conrad is obsessively still making revisions, and because he’s distracted by the jolting of the train, he lies down on his stomach so he can correct the pages on the floor. As the train pulls into their London station, Ford taps Conrad on the shoulder. But Conrad is so immersed in the world of Cuban pirates, says Ford, that he springs up and grabs Ford by the throat. Ford’s details often seem too exaggerated for some readers. Would Conrad really have gone for his friend like that? Would he really have hazarded his city clothes on a train carriage floor? The fact that the details change from version to version shows how fluid they are to Ford’s imagination, but there’s at least a grain of plausible truth. Here it’s the power of literature to engross its readers, so that one could be genuinely startled when interrupted while reading minutely. So, as with many of Ford’s stories, it’s a story about writing, writers, and what Conrad called “the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel… before all, to make you see.” And perhaps one of the things Ford wants us to see in this episode is how any aggression between friends who are writers needs to be understood in that context — as motivated as much by their obsession with words, as by any personal hostilities.

That is why a writer’s life — especially the life of a writer like Ford — is a dual one. As many of them have observed, writers live simultaneously in two worlds: the social world around them, and world they are constantly constructing in their imaginations. Impressionism seemed to Ford the method that best expressed this:

I suppose that Impressionism exists to render those queer effects of real life that are like so many views seen through bright glass — through glass so bright that whilst you perceive through it a landscape or a backyard, you are aware that, on its surface, it reflects a face of a person behind you. For the whole of life is really like that; we are almost always in one place with our minds somewhere quite other.

Ford’s life was dual in another important way, though. Like many participants, he felt the First World War as an earthquake fissure between his pre-war and post-war lives. It divided his adult life into two. His decision to change his name (after the war, which he had endured with a German surname), and to change it to its curiously doubled final form, surely expresses that sense of duality. Ford was in his early forties when he volunteered for the Army — something he could easily have avoided on account not only of his age, but of the propaganda writing he was doing for the Government. His experience of concussion and shell-shock after the Battle of the Somme changed him utterly, and provided the basis for his best work afterwards. Though he wrote over eighty books, most of them with brilliance and insight, two masterpieces have stood out: The Good Soldier, which seems the culmination of his pre-war life and apprenticeship to the craft of fiction, and then the Parade’s End sequence of four novels, which drew on his own war experiences to produce one of the great fictions about the First World War, or indeed any war.

Max Saunders is Director of the Arts and Humanities Research Institute and Professor of English and Co-Director at the Centre for Life-Writing Research at King’s College London. He is the author of Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life, editor of the Oxford World’s Classic edition of The Good Soldier, and editor of Some Do Not… (the first volume of Ford’s series of novels Parade’s End).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about The Good Soldier on the

View more about Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life on the

Image credits: Still from BCC2 adaption of Parade’s End. (Source: bbc.co.uk); Portrait of Ford Madox Ford (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The John Updike Society has finalized a contract to purchase John Updike‘s home for $200,000.

The John Updike Society has finalized a contract to purchase John Updike‘s home for $200,000.

Located in the Pennsylvania town of Shillington, Updike lived in the home for thirteen years as a child. John Updike Society president James Plath announced that the organization plans to make the house a historic site and convert it into an operational museum.

Here’s more from Reading Eagle: “Out of respect for the residential neighborhood, Plath said, he expects the historic site to be open only by appointment and not list regular hours. Plath said he has researched the operations of similar historic sites that were once authors’ homes, including the Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians in Columbus, Ga., and the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum in Montgomery, Ala.”

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

The John Updike Society has finalized a contract to purchase John Updike‘s home for $200,000.

The John Updike Society has finalized a contract to purchase John Updike‘s home for $200,000.

Located in the Pennsylvania town of Shillington, Updike lived in the home for thirteen years as a child. John Updike Society president James Plath announced that the organization plans to make the house a historic site and convert it into an operational museum.

Here’s more from Reading Eagle: “Out of respect for the residential neighborhood, Plath said, he expects the historic site to be open only by appointment and not list regular hours. Plath said he has researched the operations of similar historic sites that were once authors’ homes, including the Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians in Columbus, Ga., and the Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum in Montgomery, Ala.”

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

The Old Man and The Sea by Ernest Hemingway

Another installment of ONE STAR REVIEWS for Ernest Hemingway’s THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA.

i had to read this for english class a few years back…yuck. this was probably one of the most boring, simple books i’ve ever read…i realize hemingway writes very simply but jeez….here’s the plot…this old man goes out into the sea with a dinky little boat….he fishes…and fishes…and fishes…and fishes…then some sharks come..he fights them..they come again…and again…and eat what he has caught…and then….here’s the climax…he goes home…Zzzzzzzz

View Next 13 Posts

Scribner, an imprint at Simon & Schuster, has launched a new digital publication called

Scribner, an imprint at Simon & Schuster, has launched a new digital publication called  Ninja Essays has created an infographic called, “

Ninja Essays has created an infographic called, “

AbeBooks has released a list of

AbeBooks has released a list of

I don’t like him either. His macho schtick gets on my nerves and puts me off. Have you seen the movie Midnight in Paris? It has a brilliant satire of him. I love your closing line in this post.

(FYI, I clicked over here from the blog thread on AW.)

yeah I mostly agree. also, so much of Hemingway is about distance and direction — like ahead 200 yards, rising to the left from the road blah blah — which is so confusing to me because I can’t compute that information. He’s pretentious in his unpretentiousness. When’s the last time you read Fitzgerald? That’s a writer I can, and have, read over and over and over. The difference between, IMO, a mechanic and poet (Hemingway and Fitzgerald).

He’s pretentious in his unpretentiousness.

Ha! Perfect!!

Yes, I love Fitzgerald. Love, love, love. The Great Gatsby is one of the best books of all time and a novel I hold very dear to my heart. Their differences, despite their shared era, are immense.

Oh my gosh, I love Midnight in Paris! Such a perfect look at the guy–a perfect look at the entire Lost Generation, really. Glad you enjoyed the blog post

It’s all right not to join the choir, really. “Papa” was an original stylist in his day, and this will always be a mark of distinction.

I have the opposite problem- *loving* books no one heard of. That’s all right, too.

As long as we love some random book, it’s all good. Preferably, several books

Sara – I KNEW I’d like your review of “Sun.” I also enjoyed some of the comments it engendered. Other than the short stories,I can’t find time to re-read any of his work anymore. Actually, because of Papa, I created one of the better laughs of my lifetime. It’s February, 1972,and I’m living in Los Angeles, awakened early one morning by a very serious earthquake that took down my chimney and half-emptied my swimming pool. Now this was a time before email, before computers, and Western Union was a logical way in which to connect with people. That afternoon I drove to the nearest Western Union office and sent to a good friend—and my comedy-writing partner for TV—a telegram which read,in its entirety: “The earth moved. Truly.”

Girl, Hemingway is an acquired taste for sure! I definitely gravitated toward his work in college, but I think that was because I wanted to learn from the brevity of his prose. My fiction writing as a freshman (God help us) was incredibly verbose and WAY too flowery. Reading Hemingway taught me to create meaningful dialogue and how to edit my own work so it wasn’t overdone. So, for that, I’ll always hold a soft spot in my heart for his work…I, however, enjoyed The Paris Wife much more than The Sun Also Rises…And the satire of him in Midnight in Paris is truly fabulous!

Ahhhahahahahaaaa! I love that we can at least use Hemingway for comic references Wonderful! And I’m sure much appreciated by your friend!

Wonderful! And I’m sure much appreciated by your friend!

But I LIKE your flowery prose. You’re right; you are an excellent editor, however, so we’ll thank him for that. I’m just glad you didn’t turn into a Hemingway minion; we would have lost out on some of your most beautiful and impressive talents!