We spend a week or so sharing stories, and building excitement for writing stories. We hand out notebooks with fanfare, and writers happily personalize them. They brainstorm ideas for stories they could write.… Continue reading ![]()

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: narrative, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 53

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing process, observations, narrative, challenges, assessment, writing workshop, launching writing workshop, Add a tag

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, inspiration, narrative, writing workshop, personal narrative, Add a tag

I've been thinking about why young writers struggle with personal narrative and realistic fiction writing.![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, giveaway, mentor texts, writing workshop, Aaron Reynolds, Nerdy Birdy, Add a tag

When I first opened Nerdy Birdy by Aaron Reynolds, I was not (yet) reading it with the eye of a writer. I was way too smitten with the bird on the front cover. I mean,… Continue reading ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: picture book, poetry, Read Aloud, primary grades, narrative, immersion, persuasive writing, informational writing, argument writing, Add a tag

Janiel Wagstaff's books will help you teach primary writers about the four types of writing in an engaging way. Leave a comment on this post for a chance to win her series of Stella books.![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: poetry, narrative, immersion, Read Aloud, primary grades, persuasive writing, informational writing, argument writing, picture book, Add a tag

Janiel Wagstaff's books will help you teach primary writers about the four types of writing in an engaging way. Leave a comment on this post for a chance to win her series of Stella books.![]()

Blog: places for writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, Calls, true stories, Add a tag

The Chaos is a new journal of personal narrative, publishing true stories of personal growth, lessons learned, life-changing events, and milestones from emerging and established writers. From the editor: “We’re looking for the stories you are afraid to tell, but know you must” — unique perspectives on familiar experiences, writing that ventures into the mind of the writer or the scene of the story. Deadline: Rolling.

Add a CommentBlog: places for writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, essay, Calls, July 2016, Add a tag

It’s Not Personal is a new project inspired by the female dating experience. Looking for art and writing submissions that are related to the topic of dating. The final project will be a magazine or book with a likely publication date of Fall 2016. Deadline: July 15, 2016.

Add a CommentBlog: places for writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, essay, Calls, Add a tag

immix Magazine (US), a new online journal focused on social justice matters, seeks essays, personal narratives and political cartoons for their first issue. Length: 5000 words max. Topics must be related to social justice or other social matters. Encourages pieces on gender/sexuality, health, politics, and the environment. After first issue, rolling deadline.

Add a CommentBlog: places for writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: memoir, Contests, nonfiction, narrative, essay, March 2016, Add a tag

Entries open for The Monadnock Essay Collection Prize. Submit a book-length collection (120-160 pages or 50,000-60,000 words) of nonfiction essays: personal essays, memoir in essay form, narrative nonfiction, commentary, travel, historical account, etc. Prize: $1000, publication and 100 copies of the published collection, and distribution with other titles. Entry fee: $30. Deadline: March 1, 2016.

Add a CommentBlog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, future, Kim Stanley Robinson, novels, science fiction, Add a tag

To make Kim Stanley Robinson's Aurora make sense, I had to imagine a metafictional frame for it.

The novel tells the story of a generation starship sent in the year 2545 from the Solar System to Tau Ceti. It begins toward the end of the journey, as the ship approaches its destination and eventually sends a landing party to a planet they name Aurora. The narrator, we quickly learn, is the ship's artificial intelligence system, which for various reasons is learning to tell stories, a process that, among other things, helps it sort through and make sense of details. This conceit furthers Robinson's interest in exposition, an interest apparent at least since the Mars trilogy and explicit in 2312. As a writer, he seems most at home narrating scientific processes and describing the features of landscapes, which does not always lead to the most dynamic prose or storytelling, and he seems to have realized this and adjusted to make his writerly strengths into, if not his books' whole reason for being, then a meaningful feature of their structure. I didn't personally care for 2312 much, but I thought it brilliantly melded the aspirations of both Hugo Gernsback and John W. Campbell for science fiction in the way that it offered explicit, even pedagogical, passages of exposition with bits of adventure story and scientific romance.

What soon struck me while reading Aurora was that aside from the interstellar travel, it did not at all seem to be a novel about human beings more than 500 years in the future. The AI is said to be a quantum computer, and it is certainly beyond current computer technology, but it doesn't seem breathtakingly different from the bleeding edges of current technology. Medical knowledge seems mostly consistent with current medical knowledge, as does knowledge of most other scientific fields. People still wear eyeglasses, and their "wristbands" are smartwatches. Historical and cultural references are to things we know rather than to much of anything that's happened between 2015 and 2545 (or later — the ship's population seems to have developed no culture of their own). The English language is that of today. Social values are consistent with average bourgeois heterosexual American social values.

500 years is a lot of time. Think about the year 1515. Thomas More started writing Utopia, which would be published the next year. Martin Luther's 95 Theses were two years away. The rifle wouldn't be invented for five more years. Copernicus had just begun thinking about his heliocentric theory of the universe. The first iterations of the germ theory of disease were thirty years away. The births of Shakespeare and Galileo were 49 years in the future. Isaac Newton wouldn't be born until the middle of the next century.

Aurora offers nothing comparable to the changes in human life and knowledge from 1515 to 2015 except for the space ship. The world of the novel seems to have been put on pause from now till the launch of the ship.

How to make sense of this? That's where my metafictional frame comes in. One of the stories Aurora tells is the rise to consciousness of the AI narrator. Telling stories seems to be good for its processors. Much of the book is quite explicitly presented as a novel by the AI — an AI learning to write a novel. Of course, within the story, it's not a novel (a work of fiction) but rather a work of history. Still, as it makes clear, the shaping of historical material into a narrative has at least as much to do with fiction as it does with history.

It's easy to go one step further, then, and imagine that the "actual" history of the AI's world is outside the text. The text is what the AI has written. The text could be fiction.

It could, for instance, be a novel written by an AI that survived the near-future death of humanity, or at least the death of human civilization.

What if the "actual" year of the novel is not near the year 3000, but rather somewhere around 2050. Global warming, wars, famine, etc. could have reduced humanity to nearly nothing just at the moment computer technology advanced enough to bring about a quantum computer capable of developing consciousness and writing a novel. What sort of novel might an AI learn to write? Why not a story about a heroic AI saving a group of humans trapped on a generation ship? An AI that helps bring those humans home after their interstellar quest proves impossible. An AI that, in the end, sacrifices itself for the good of its people.

This helps explain the change of narrators, too. At the end of Book 6, the ship has returned the humans to Earth and then accelerates on toward the sun, where, we learn later, it burns up. Book 7 is a traditional third-person narrative. This is a jarring point of view shift if the AI actually burned up in the sun. (And how did its narrative get saved? There's some mention of the computer of the ferry to Earth having been able to copy the ship AI, though also mention that such a copy would be different from the original because of the nature of quantum computing.)

But if we assume that the AI narrator is still the narrator, then Book 7 is the triumph of the computer's storytelling, for Book 7 is the moment where the AI gets to disappear into the narration.

Wouldn't it be fun for an AI to speculate about all the possible technological developments over 500 years? Perhaps, but only if its goal was to write a speculative story. It might have a more immediate goal, one that would require a somewhat different story. It might be writing not to entertain or to offer scientific dreams, but to provide knowledge and caution for the few survivors of the crash of humanity.

Book 7 tells us to value the Earth, our only possible home. It shows a human being who has never been to Earth coming to it and learning how to love it. The moment is religious in its implications: the human being (our protagonist, Freya) is born again. Just as the AI is born again into the narration, so Freya is born into Earthbound humanity. There is hope, but the hope relies on living in harmony with the only possible planet for humans.

The descendants of the last remnants of humanity, scrambling for a reason to survive on a planet their ancestors battered and burned, might benefit from such a tale. (Also: One of the implicit messages of the story is: Trust the AI. The AI is your friend and savior.)

Viewed this way, Aurora coheres, and its speculative failures make sense. It is a tale imagined by a computer that has learned to tell stories, a cautionary fairy tale aimed perhaps at the few remaining people from a species that destroyed its only world.

Blog: andrea joseph's sketchblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: illustration, storytelling, story, narrative, AJ, andrea joseph, Andrea Joseph drawings, drink and draw, New Mills, alternative life drawing, The Red Case, The Studios, Add a tag

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, Artists, Mike Leigh, Movies, history, biography, film, Add a tag

Two new biographical films give viewers an opportunity to see diametrically opposite approaches not just to biography, but to film narrative itself.

A warning: I saw Mr. Turner and The Imitation Game months ago (as part of the annual Telluride at Dartmouth festival), and my thoughts here are based purely on memories that are getting ever dimmer. Nonetheless, the differences between the films are so striking that I couldn't help but keep thinking about them, to keep reading about the stories' subjects, and to keep coming back to the idea of how information is conveyed through moving pictures.

I went into both films with relatively high expectations, since I adore Mike Leigh's work and I had very much enjoyed Headhunters, the previous movie directed by Imitation Game's Morten Tyldum. And overall I did like both Mr. Turner and The Imitation Game; however, "like" is part of a broad spectrum, and for me, Mr. Turner was a powerful emotional and aesthetic experience that made it among the best movies I've seen in a long time, and The Imitation Game was an entertaining way to spend a couple hours.

The audience responses to the two films were interesting, in that The Imitation Game seemed to be a real crowd-pleaser, while Mr. Turner... Well, let's see. There was a couple behind us who didn't seem to be having a very good time, and somewhere in the distance somebody was snoring, then when we walked out to the lobby, a couple of nice young Dartmouth students working as ushers stopped me and one of my companions: "We're sorry," they said, "but we just need to know — what did you think of that?" I think my companion said she thought it was pretty but that Timothy Spall's performance was very off-putting, and I think I mumbled out something like, "Bloody genius! Overwhelming!" The students clearly found it almost an impossible film to even have an opinion of, a film that was so outside their protocols of evaluation that it might as well have been an alien object.

The Imitation Game takes very good care of its audience. It works hard to keep the viewer from confusion, it provides plenty of exposition, its score sets up emotional moments, and it simplifies the history it represents so determinedly that it is, in the most shallow sense of the word, satisfying: it fits its subject to the limitations of a limited form. It's the cinematic equivalent of a TED Talk.

Mr. Turner is not much interested in providing the viewer with exposition. Its narrative approach could be described as starting from the middle of in medias res. It doesn't explain who its characters are, what their relationships to each other are, or why they behave the way they do. As viewers, we're required to pick up on cues, like strangers in a new city or guests at a party where we don't know anybody. It's a deeply internalized narrative form, and it can feel unstructured, though it's not at all. It's vaguely akin to cinema verité, but perhaps closer to Chekhov's plays, which David Magarshack astutely described as plays of "indirect action".

Indeed, in some ways what we see with The Imitation Game and Mr. Turner is not so much an aesthetic difference between biopics, but a much deeper and older difference: that between the well-made play and realism. This is not to say that The Imitation Game works like a Scribe play, but rather that it sticks to old narrative conventions of character relations, suspense, and denouement, and it does so quite skillfully — it's no surprise that it topped the Black List of unproduced screenplays in 2011, because it shrinks the story of Alan Turing into a pleasing and recognizable form.

Mr. Turner is far less interested in fitting its tale into a familiar form. Instead, white Mike Leigh and his accomplices have done is take some of the actual history of J.M.W. Turner in his later years (mostly the last decade of his life) and roam around in it, dramatizing not only the known history but also some of the amusing tales and rumors that rose up around him (good stories, but unverifiable). The desire of the film seems to be not to teach us anything, but rather to let us hang around in some of the moments of Turner's life. It concludes with his death, but not in any satisfying way — instead, we are left with the uncomfortable sense of missed opportunities and incomplete actions that accompanies the end of even the longest of lives. For the viewer who has been able to enter into the movie's indirect approach, to feel a way into the film's feelings, it's profoundly moving. For the viewer who hasn't, the effect is bewildering, anticlimactic, and just plain odd, a mix of "That's it?" and "So what?"

For me, the narrative approach of Mr. Turner seems more honest and respectful toward the history than the approach of The Imitation Game, where a complex history is quite severely reduced so as to make it more dramatically comprehensible and familiar. It's odd that The Imitation Game has to give credit to Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges; it would be more accurate to credit the film as "based on a handful of sentences in a big book by Andrew Hodges and a whole lot of imagining by Graham Moore". Some people have criticized it for not depicting Turing's homosexuality enough, and there's something to that, though it's not so much a lack of attention to his sexuality as a question of emphasis and detail — the BBC film of Hugh Wheeler's play Breaking the Code is far more effective at conveying the complexities and realities of homosexuality in Turing's life. (For The Imitation Game, it seems it's the chemical castration that's the most interesting part of Turing's sexual history, since it leads to a climactic weepy moment.)

While Mr. Turner is not remotely a documentary, and admittedly adds in a few events that are likely untrue, on the whole it is remarkably faithful to what is known and what can be known about Turner's life and era. Leigh can accomplish this because he doesn't feel any need to force the film into the form of a traditional story. By abandoning the most traditional, familiar conventions of storytelling, he's free to keep things as odd and messy as they may have been in real life.

Both films are carried by their lead actor, but again the differences are sharp. Benedict Cumberbatch plays Turing as the cousin of his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes. It's a generally endearing portrayal; nobody makes this sort of character as charming and delightful as Cumberbatch, and he's in danger of typecasting. (I love his Sherlock, but am most impressed by him as an actor in Parade's End, because there he had a truly difficult acting challenge: to convey meaning and emotion while portraying someone who has deeply repressed their emotional life. It's an extraordinary acting challenge because it requires that the actor do as little "acting" as possible, and it is that sort of challenge — not the showy Oscar-bait stuff — that separates the great actors from the merely talented. I would have preferred more of that performance in Cumberbatch's Turing and less of Sherlock.) But there's also something plastic about the performance, something that seems to me more appropriate for a comedy — I sometimes thought Cumberbatch edged toward Michael Palin territory.

Timothy Spall's performance as Turner is astounding, but also, for many people, so off-putting that it makes actually watching the movie difficult. (Or so they told me.) For me, it was riveting, because though Spall snarls and growls and mutters and spits his way through the movie, it's not a grandstanding performance because the physicality is so at odds with an inner life that Turner struggles to communicate and that only fully comes out in his art. One of my favorite scenes in the film has Turner standing at a piano as a woman plays it. He is clearly moved by the music. Then, he starts singing. He's a terrible singer, of course, but he so commits himself to the song and so lets the music sink into himself that the moment is extraordinarily complex: we want to laugh, yes, because it's like watching an overgrown hamster try to sing like Pavarotti, but quickly we also can't help but see the human being within, the rough son of a barber who taught himself to appreciate so much that was considered high-class and beyond him, the great artist trapped in the man's body. It's a moment absurd, beautiful, and sad all at once. That's the strength of this film, the greatness of its art: it is absurd, beautiful, sad, horrifying, weird, funny, beguiling, and so much more all at once.

The other performances are as layered and interesting as we've come to expect from Leigh (although Joshua McGuire's portrayal of John Ruskin, while hilarious, seemed a bit too over the top in comparison to the other performances in the film). Dorothy Atkinson deserves every award out there for her performance as Turner's housekeeper, Hannah Danby — she transformed herself even more fully than Spall, but is similarly capable of conveying extraordinary amounts of emotion and information through glances, gestures, and posture. It's a performance that, like Spall's, could easily have become caricature, but rises to far greater heights.

The cinematography in Mr. Turner is also extraordinary. (I remember nothing of the cinematography of The Imitation Game.) The way that Leigh and his director of photography Dick Pope are able to set up shots and capture light is not precisely Turneresque (though a few scenes from Turner paintings are reproduced); instead, it creates the feeling of showing us the kind of light that Turner would have interpreted through paint. It allows us to imagine that we see not Turner's paintings, but what Turner painted, and what he saw in the world that inspired him toward painting. (In that sense, it reminds me of Jean Lépine's magnificent cinematography in Vincent & Theo, another great film about a great artist.)

I expect The Imitation Game will be up for more awards than Mr. Turner, because The Imitation Game is such an easy film to like — it's the nice guy you're always happy to have over for dinner because he can get along with anybody and he always has a few amusing stories to tell. But you're happy he also goes home after a couple of hours, because really he doesn't have a lot to offer. Mr. Turner is thornier, a movie that, like its subject, makes no effort to be likeable, and so in the end is something much more than likeable: a work of art that trusts its audience to catch up, to play along, to reflect and wonder, and to live with complexities of ordinary, extraordinary life.

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: film, Quotes, Hitchcock, narrative, plausibility, Add a tag

Alfred Hitchcock in conversation with Francois Truffaut:

To insist that a storyteller stick to the facts is just as ridiculous as to demand of a representative painter that he show objects accurately. What's the ultimate in representative painting? Color photography. Don't you agree? There's quite a difference, you see, between the creation of a film and the making of a documentary. In the documentary the basic material has been created by God, whereas in the fiction film the director is the god; he must create life. And in the process of that creation, there are lots of feelings, forms of expression, and viewpoints that have to be juxtaposed. We should have total freedom to do as we like, just so long as it's not dull. A critic who talks to me about plausibility is a dull fellow.

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: storytelling, narrative, three act structure, David Thorpe, Add a tag

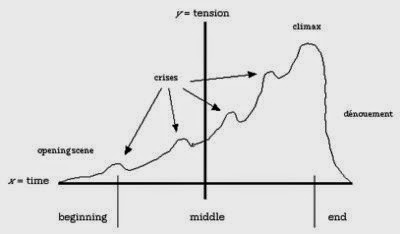

This is weird. For years I went by the standard Hollywood scriptwriting rule which says that the three act structure is god. As it was taught to me in my scriptwriting class and as I taught it to hundreds of students, in a standard drama act one finishes one quarter of the way in and act three begins one quarter before the end. There's also a midpoint where there's another not quite so pronounced change of direction or momentum.

I tested it out many times with my watch while watching movies and even when writing scripts, counting the number of pages in, to confirm that at these magical points the main plotline undergoes a major shift of direction or gear. Of course you all know this.

Plenty of stories do not quite conform to this rule (usually short or very long or episodic ones) and post-modern writers mess about with it. If there are many subplots or intertwining storylines there will also be distortion, but you can often pick apart these individual storylines and apply the same rule to them.

It's not as if this is deliberate. It seemed to be an intrinsic quality of the way the human mind appreciates the telling of a story and, correspondingly, the writing of one.

Now the novel I am principally engaged on right now has an unusual storyline: it is circular, so in principle has no beginning, middle or end. It's a story (and I don't want to give too much away) that I had been wrestling with how to tell since I first thought of the idea almost half a lifetime ago.

Many times I came to it, tried to write the opening pages and got nowhere. I put it down but it kept bothering me. I knew there was a really good idea in there somewhere. But because it was circular I couldn't get a handle on it, from a dramatic point of view. There were other issues: I needed to do research and at the time wasn't fully capable of it. Some stories have very long gestation period.

Sometimes when you are struggling with a problem like this you read another novel that is quite different and it can give you a sudden insight into your own story, and for me in this particular case it was reading The Raw Shark Texts by Steven Hall which is a very curious book indeed. In case you haven't read it, it is about creatures which exist beneath the surface of a page when you are reading a book which have a life of their own and if you're not very careful they can devour you.

That's quite a powerful idea. It gave me another idea, also, I like to think, powerful. I put it into my mix.

The second new ingredient came from reading a non-fiction book, The End Of Time by Julian Barbour, which argues that time does not exist – except in our consciousnesses. It's quite possible to describe the universe mathematically without recourse to time, he argues.

But if there is no time, how can a story have beginning, middle or end? In fact, how can there be stories at all? Logically, outside of our consciousnesses, stories are impossible. They do not exist 'out there'. We invent them to entertain each other and help ourselves remember stuff.

The third and final necessary ingredient for me to get a handle on my story was to determine the point of view. Up to then I did not have one, other than that of an omniscient narrator. It all fell into place when I realised that I needed a new character from whose perspective everything else was told. Once this had dawned on me, and I'd decided upon who that character was and his relationship to the other protagonists, the story could be written.

First I wrote the synopsis, then a long treatment. I needed to have it all plotted out because it was very complicated. Two years later I found the time to write the first draft and completed it by summer 2013. I left it for nearly a year and then completed the second draft last month.

I then thought I would try an experiment, and I looked at what happened precisely one quarter, one half, and three quarters of the way through the draft. Lo and behold, there were the plot points – in exactly the places where the theory said they should be.

How did this happen? I have a hypothesis, but that's all. Even though the story is circular I had to start it somewhere. Given that my narrator is deliberately telling the story for the benefit of another character in the novel, then the story begins at the most significant entry point for him. He then recounts the story until he reaches the point at which there is a suitable ending for him. This is just his perspective on the events.

Another character might have begun to describe the events at a different temporal point. Nevertheless I chose the character of the narrator, and therefore I am ultimately responsible for choosing where the novel starts to describe the circle of events, and it made total sense to start it there once I had made that choice.

I am incapable, however, of working out whether the final emergent structure is subconsciously imprinted into the novel because it is so deeply engrained in my own mind – as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy – or whether it would have been there anyway. I know that I needed to establish the characters and the situation before the story could really take off, and I know that the pacing and dramatic intensity needed to increase as the narrative progresses. So I surmise that I had probably adopted the structure and these principles without deliberate intention.

It's vaguely satisfying to know that this happens automatically but also slightly disturbing. I have felt, at times, like dividing the chapters or episodes up and randomly shuffling them to see if anything interesting emerged from the new ordering, but intuitively I suspect that might be a waste of time. An interesting experiment nonetheless. Perhaps I still ought to do it.

I think Barbour is right, and time – therefore stories – do only exist in our minds. Story structure is a necessary consequence of consciousness because we cannot appreciate what comes later without knowing what has come before – whether the story is true, historical, or fiction. We also need to be made to care for the characters before we are motivated to turn the page.

We are prisoners of time and so bound to the logic of narrative. We seek beginnings, middles and ends even where there are none.

I wonder if any of you have similar experiences your own writing processes?

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: short stories, narrative, Vikram Chandra, India, queer, Add a tag

Vikram Chandra's collection of interconnected stories, Love and Longing in Bombay, is a book I had thought of writing about in some detail, but I'm afraid time is not on my side with that, and a number of other writing projects need attention. One story I managed to make some notes on is "Artha", and here are those notes, in case some thoughts on the story are useful to someone else...

In thinking about Love and Longing in Bombay, I’m going to start by grasping some tiny pieces within the wholes, and see what I can do with them.

First, a single story, and a single page of that story, and not the words but the blank space.

The story: “Artha”. The page: 165 of the 1998 Back Bay Books paperback edition.

The two blank spaces between narrators and their narratives.

The first narrative is the introduction common to all of the stories, a frame that remains mysterious until “Shanti”, the final story. If we assume, as I think we can, that the narrator of the introductions is the same in each of the stories, then his name is Ranjit Sharma.

The second narrative is that spoken by Subramaniam, who has been the putative narrator (storyteller) of the previous tales within the frame.

But “Artha” becomes distinctive with the next blank space, for here we are ushered into yet another story, that told by “the young man” to Subramaniam. The young man’s name is Iqbal. He will be the narrator for the remainder of the tale.

Another item of distinction: after each blank space, the speaker is identified within parentheses. Previously, there has been no need for this. Now, though, there must be no mistake. Is the reason that there is a story-within-the-story? Possibly, but I’m not convinced of that, because the transitions into the tales are no more confusing than those in previous parts of the book, and the multiple embedded stories in the only remaining tale, “Shanti”, are, arguably, more confusing and do not have such clear, interrupting markers.

Let’s return to the idea of the blank space for a moment. Printers, or so I’ve been told, call these spaces “slugs”. I like the positive sense of that, rather than the negative of blank space. Slugs are an insertion, a something. Slugs disrupt the text from within — they give it order and shape by signaling some unspoken drift, thus taming what would otherwise be a jarring slip, an incoherence, by making it visible. The slug is a sign: Mind the gap.

Once we’ve minded that gap, though, we get a stutter in the story: “(Subramaniam said)”, “(the young man said)”. I shall now indulge in a moment of paranoid reading: Are these stutters a distancing technique inspired by the über-narrator’s fear of being mistaken for a homosexual? The parenthetical speech tags are unnecessary; they are excessive intrusions, and, unless my memory and notes are failing me, the only such intrusions into embedded narratives anywhere in a book comprised of embedded narratives. (The most complex such embeddings are achieved in “Shanti” via typographical changes — separated visually from the main text, but without their own text interrupted.)

We should note, though, that even if we assume that the parenthetical speech tags are motivated by the über-narrator’s fear-laden desire to distance himself from any perception of being a/the homosexual man, the insertion of “(the young man said)” puts those words within the homosexual text. Ranjit’s words enter Subramaniam’s story, and then Subramaniam’s words enter Iqbal’s. All of these words are part of one text, “Artha”, that is part of a larger text, Love and Longing in Bombay. The attempt to create distance from the homosexual narration has, paradoxically, done exactly the opposite. It is not the homosexual narration that desires separation, but the heterosexist; the heterosexist narration’s effort to separate and distance itself has placed it within the homosexual narration.

(Now would be the time — this would be the space — to discuss mimicry and postcolonialism. I am not going to do so. Instead, consider this paragraph a slug.)

Walter Benjamin wants to get into the conversation. Here he is, via Mark Jackson:

The arcade [says Jackson] acted as a spectacular landscape that opened up the city as an illusory, sleepy, standstill world of the phantasmagoria, while at the same time, in the form of the more intimate and decided ambiguous, street-but-not-street of the arcade, it closed around the modern subject as if a room, reassuring with “felt knowledge” (Benjamin, 1999, p. 880) intuitive semblances of domestic wish fulfillment. (39)The idea of the arcade as street-but-not-street could be extended to the idea of Love and Longing in Bombay as an arcade, a book of x-but-not-x. How do we solve for that x? Can we locate an “illusory, sleepy, standstill world of the phantasmagoria” within the book? For Jackson-via-Benjamin, commodities are phantasmagoric, and “phantasmagoria” is a quality of mystification and even misrecognition: “Desired and consumable things, they embodied and thus represented, dreamt wish images of futurity, and, at the same time, the imminent (and immanent) undoing of that indwelling mythic aspiration” (38)

Must phantasmagoria always be mystifying? Is mystification itself always undesirable?

I would like to keep open the question of phantasmagoria’s usefulness, for as a mode of fantasy it should (shouldn’t it?) possess some of the power of fantasy to reveal structures and discourses of desire otherwise inaccessible.

Is it meaningful to suggest that the insertions of speech tags into the narrations of “Artha” are traces of phantasmagoric desire? That the otherness of Iqbal — located not only in his sexual identity, but his name, which indicates religion — is itself desired. But desired how? To what end? Perhaps the cosmopolitanism of the post-colonial/post-modern city, the place where identities can flow into each other, where mimicry and fantasy themselves create identities (for, after all, isn’t identity without any trace of mimicry and fantasy illegible?). Iqbal as we receive him is not Iqbal, but rather the voice of Iqbal mediated through the voice of Subramaniam mediated through the voice of Ranjit, and all of which is constructed by Chandra.

The arcade of voices, the phantasmagoria of identification.

For Iqbal, religious difference can be dismissed “in one smile” (198) if desire is present. Perhaps that is what the inserted speech tags, and their paradoxes, suggest. The simultanous desire not to be mistaken for a homosexual and to be part of the narrative of the homosexual.

To walk the arcade.

To fantasize.

To be present without losing identity.

To smile.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books, Religion, nature, science, bible, narrative, wisdom, lightning, theology, thunder, George Steiner, Humanities, *Featured, natural science, Science & Medicine, Earth & Life Sciences, Bruno Latour, faith and wisdom in science, tom mcleish, mcleish, Add a tag

By Tom McLeish

There is a pressing need to re-establish a cultural narrative for science. At present we lack a public understanding of the purpose of this deeply human endeavour to understand the natural world. In debate around scientific issues, and even in the education and presentation of science itself, we tend to overemphasise the most recent findings, and project a culture of expertise.

The cost is the alienation of many people from experiencing what the older word for science, “natural philosophy” describes: the love of wisdom of natural things. Science has forgotten its story, and we need to start retelling it.

To draw out the long narrative of science, there is no substitute for getting inside practice – science as the recreation of a model of the natural world in our minds. But I have also been impressed by the way scientists resonate with very old accounts nature-writing – such as some of the Biblical ancient wisdom tradition. To take a specific example of a theme that takes very old and very new forms, the approaches to randomness and chaos are being followed today in studies of granular media (such as the deceptively complex sandpiles) and chaotic systems.

These might be thought of as simplified approaches to ‘the earthquake’ and ‘the storm’, which appear in the achingly beautiful nature poetry of the Book of Job, an ancient text also much concerned with the unpredictable side of nature. I have often suggested to scientist-colleagues that they read the catalogue of nature-questions in Job 38-40, to be met with their delight and surprise. Job’s questioning of the chaotic and destructive world becomes, after a strenuous and questioning search in which he is shown the glories of the vast cosmos, a source of hope, and a type of wisdom that builds a mutually respectful relationship with nature.

Reading this old nature-wisdom through the experience of science today indicates a fresh way into other conflicted territory. For, rather than oppose theology and science, a path that follows a continuity of narrative history is driven instead to derive what a theology of science might bring to the cultural problems of science with which we began. In partnership with a science of theology, it recognises that both, to be self-consistent, must talk about the other. Neither in conflict, nor naively complementary, their stories are intimately entangled.

Cloud to ground lightning over Sofia, by Boby Dimitrov. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The strong motif that is the idea of science as the reconciliation of a broken human relationship with nature. Science has the potential to replace ignorance and fear of a world that can harm us and that we also can harm, by a relationship of understanding and care. The foolishness of thoughtless exploitation can be replaced by the wisdom of engagement. This is neither a ‘technical fix’, nor a ‘withdrawal from the wild’, two equally unworkable alternatives criticised recently by Bruno Latour in a discussion of environmentalism in the 21st century.

Latour’s hunch that rediscovered religious material might point the way to a practical alternative begins to look well-founded. Nor is such ‘narrative for science’ confined to the political level; it has personal, cultural and educational consequences too that might just meet Barzun’s missing sphere of contemplation.

Can science be performative? Could it even be therapeutic?

George Steiner once wrote, “Only art can go some way towards making accessible, towards waking into some measure of communicability, the sheer inhuman otherness of matter…”

Perhaps science can do that too.

Tom McLeish is Professor of Physics and Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research at University of Durham, and a Fellow of the Institute of Physics, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the American Physical Society and the Royal Society. He is the author of Faith and Wisdom in Science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Faith and science in the natural world appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: SCBWI, narrative, introduction, Add a tag

Opening lines should draw readers into the world of a story & involve them from the start. ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, writer's notebook, Add a tag

How, she wondered, could we get them to write more focused narratives? And what types of entries could they make in their writer's notebooks to help them with this process?![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Melissa Guion, narrative, Oliver Jeffers, mentor texts, Add a tag

This Moose Belongs to Me and Baby Penguins Everywhere are new books with strong messages that contain craft moves we can teach young writers.![]()

Blog: Great Books for Children (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Picture Book, Picture Books, writing, narrative, stories, elementary school, pb, Add a tag

Ralph Tells a Story written and illustrated by Abby Hanlon (Amazon Children’s Publishing, 2012). It doesn’t matter if your five or twenty-five—if you’re in school, you’re gonna have to write. And lots of times you have to write stories—stories about yourself. Maybe it’s a daily journal. Maybe it’s a “My Special Moment” essay. Maybe it’s a descriptive narrative for a college composition class. Well, if you’re one of those kids who has NO IDEA what to write about and can’t think of ONE SINGLE STORY, then Abby Hanlon’s Ralph Tells a Story is the book for you. Ralph’s teacher always says, “Stories are everywhere!” and the kids in Ralph’s class have no trouble finding them. They write pages and pages and pages during writing time. But Ralph can’t come up with anything. Zero, zip, nada. So Ralph does what all smart kids do. He stalls. He goes to the bathroom. He gets a drink. He offers to help the lunch ladies. And finally, finally, Ralph thinks of the start of a story. But then he gets stuck. Which is exactly when his teacher asks him to share his story. Luckily for Ralph, his classmates ask lots and lots of questions. [...]

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: picture book, narrative, mentor texts, Add a tag

I’ve been tinkering around with the picture books I’m going to bring when I speak at WordFest later this month. My presentation focuses on using recently published picture books as mentor texts to… Read More ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, plan, Add a tag

I’ve been trying to think through how to explain thinking in scenes to young writers in a way that makes it accessible. It seems they either write two scenes and call it done… Read More ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, mentor texts, Patricia Polacco, Q & A, Add a tag

Patricia Polacco has long been one of my favorite children’s authors. I’ve led author studies of her works with my former students in both reading and writing workshop. I have used books like… Read More ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: narrative, mentor texts, lucy calkins, minilesson, tcrwp, Add a tag

I’ve been working on a few sample minilessons to give my grad students next month when I start teaching “Children’s Literature in Teaching Writing.” I’ve been making tweaks to the traditional minilesson structure… Read More ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: books, illustrations, narrative, craft, noticings, Add a tag

An eclectic little stack today. Click on the images to go to a link about the book. I’ve been enjoying books I can read a little here and a little there. This book,… Read More ![]()

View Next 25 Posts