new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: poetry, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 4,295

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: poetry in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Fun Fact: The American Library Association does not currently give an award specifically to great works of children’s book poetry. Is not that strange? When I first discovered this to be true, I was perplexed. I’ve always been a bit of a rube when it comes to the poetic form. Placing stresses on syllables and knowing what constitutes a sestina and all that. Of course even without its own award specifically, poetry can win the Newbery or the Caldecott. Yet too often when it happens it’s in the form of a verse novel or its sort of pooh-poohed for its win. Remember when Last Stop on Market Street won the Newbery and folks were arguing that it was the first picture book to do so since A Visit to William’s Blake’s Inn couldn’t possibly be considered a picture book because it was poetry? None of this is to say that poetry doesn’t win Newberys (as recently as 2011 Dark Emperor and Other Poems of the Night by Joyce Sidman won an Honor) but aside from the month of April (Poetry Month a.k.a. the only time the 811 section of the public library is sucked dry) poetry doesn’t get a lot of attention.

Fun Fact: The American Library Association does not currently give an award specifically to great works of children’s book poetry. Is not that strange? When I first discovered this to be true, I was perplexed. I’ve always been a bit of a rube when it comes to the poetic form. Placing stresses on syllables and knowing what constitutes a sestina and all that. Of course even without its own award specifically, poetry can win the Newbery or the Caldecott. Yet too often when it happens it’s in the form of a verse novel or its sort of pooh-poohed for its win. Remember when Last Stop on Market Street won the Newbery and folks were arguing that it was the first picture book to do so since A Visit to William’s Blake’s Inn couldn’t possibly be considered a picture book because it was poetry? None of this is to say that poetry doesn’t win Newberys (as recently as 2011 Dark Emperor and Other Poems of the Night by Joyce Sidman won an Honor) but aside from the month of April (Poetry Month a.k.a. the only time the 811 section of the public library is sucked dry) poetry doesn’t get a lot of attention.

So rather than relegate all poetry discussions to April, let us today celebrate some of the lovelier works of poetry out for kids this year. Because we lucked out, folks. 2016 was a great year for verse:

2016 Poetry Books for Kids

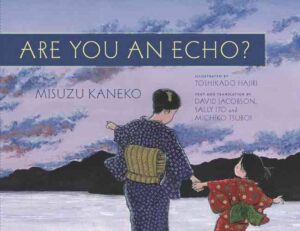

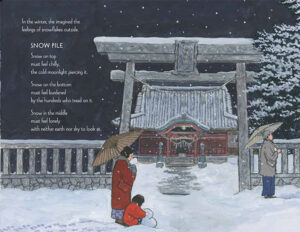

Are You an Echo?: The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko by David Jacobson, ill. Toshikado Hajiri, translations by Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi

No surprises here. If you know me then you know I’m gaga for this title. For the purposes of today’s list, however, let’s just zero in on Kaneko’s own poetry. Cynical beast that I am, I would sooner eat my own tongue than use a tired phrase like “childlike wonder” to describe something. And yet . . . I’m stuck. Honestly there’s no other way to adequately convey to you what Kaneko has done so perfectly with this book. Come for the biography and history lesson. Stay for the incomparable poems.

Freedom Over Me: Eleven Slaves, Their Lives and Dreams Brought to Life by Ashley Bryan

I’m not entirely certain that I can express in words how deeply satisfying it’s been to see this book get as much love and attention as it has, so far. Already its appeared on Chicago Public Library’s Best of the Best, its been a Kirkus Prize Finalist, it was on the NCTE Notable Poetry List, and New York Public Library listed it on their Best Books for Kids. I would have liked to add an Image Award nomination in there as well, but you don’t always get what you want. Regardless, I maintain my position that this is a serious Newbery contender. Even if it misses out during the January award season, there is comfort in knowing that folks are finding it. Very satisfying.

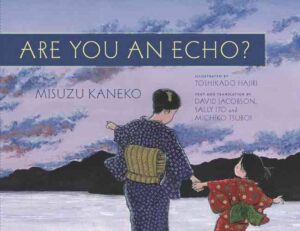

Grumbles From the Town: Mother-Goose Voices With a Twist by Jane Yolen and Rebecca Kai Dotlich, ill. Angela Matteson

Its been promoted as a writing prompt book, but I’d argue that the poetry in this collection stands on its own two feet as well. Yolen and Dotlich take classic nursery rhymes and twist them. We’ve all seen that kind of thing before, but I like how they’ve twisted them. A passing familiarity with the original poetry a good idea, though they’ve covered their bases and included that information in the back of the book as well. Good original fun all around.

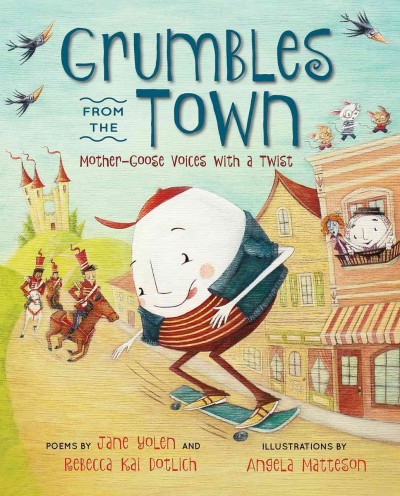

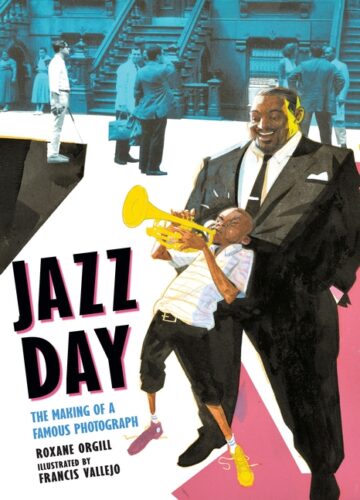

Jazz Day: The Making of a Famous Photograph by Roxane Orgill, ill. Francis Vallejo

So far it’s won the only major award (aside from the Kirkus prize) to be released so far for a 2016 title. Jazz Day took home the gold when it won in the picture book category of the Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards. And, granted, I was on that committee, but I wasn’t the only one there. It’s such an amazing book, and aside from poetry its hard to slot it into any one category. Fiction or nonfiction? You be the judge.

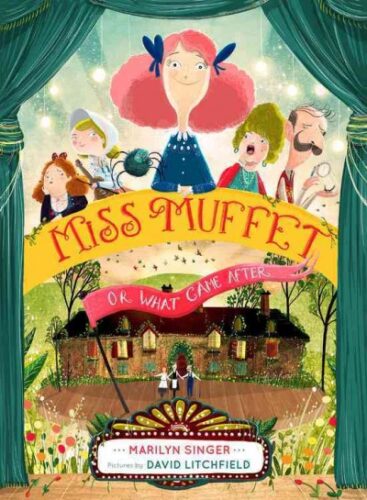

Miss Muffet, Or What Came After by Marilyn Singer, ill. David Litchfield

It’s sort of epic. From one single short little nursery rhyme, Singer spins out this grandiose tale of crushed hopes, impossible dreams, and overcoming arachnophobia. Since it’s a story told in rhyme I’m sort of cheating, putting it on this poetry list. Maybe it’s more school play than poetry book. I say, why not be both?

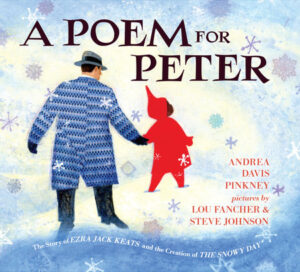

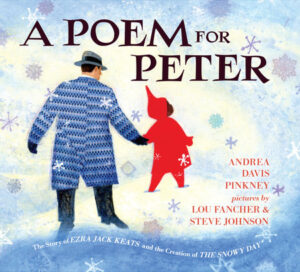

Now this book has been nominated for an NAACP Image Award, so there is some justice in this world. When I first read the description I wasn’t entirely certain how it would work. Imagine the daunting task of telling Ezra Jack Keats’ story using his own illustration style. Imagine too the difficulty that comes with using poetry and verse to tell the details of his story. Pinkney’s done poetry of one sort or another before, but I dare say this is her strongest work to date in that style.

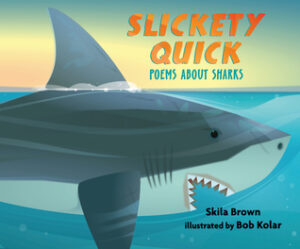

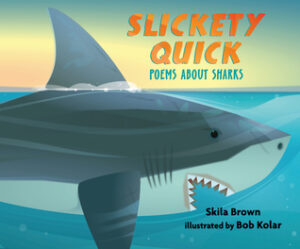

Slickety Quick: Poems About Sharks by Skila Brown, ill. Bob Kolar

From the start I liked the poems (they were smart) but since it was about real sharks I pondered that question every children’s librarian knows so well: how would it fly with kids? Well, I donated a copy to my kid’s daycare and found, to my infinite delight, that the kids in that class were CRAZY about it. Every day when I went to pick my daughter up, she and the other kids would start telling me shark facts. You’ve gotta understand that these were four-year-olds telling me this stuff. If they get such a kick out of the book (and they do) imagine how the older kids might feel!

A Toucan Can, Can You? by Danny Adlerman, ill. Various

It’s baaaaack. Yeah, this little self-published gem keeps cropping up on my lists. Someone recently asked me where they could purchase it, since it’s not available through the usual streams. I think you can get it here, in case you’re curious. And why should you be curious? Because it takes that old How Much Wood Could a Woodchuck Chuck, expands it, and then gets seriously great illustrators to contribute. A lovely book.

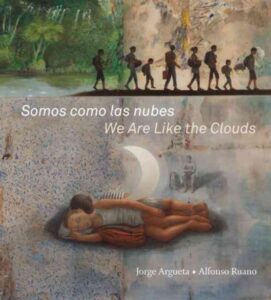

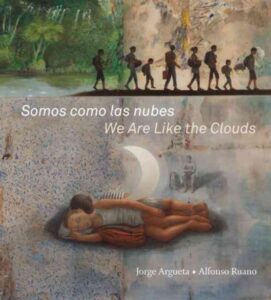

Somo Como Las Nubes / We Are Like the Clouds by Jorge Argueta, ill. Elisa Amado

Because to be perfectly frank, your shelves aren’t exactly exploding with books about refugee children from South America. That said, it’s easy to include books on lists of this sort because their intentions are good. It’s another thing entirely when the book itself actually is good. Argueta is an old hand at this. You can trust him to do a fantastic job, and this book is simultaneously necessary and expertly done. There’s a reason I put it on my bilingual book list as well.

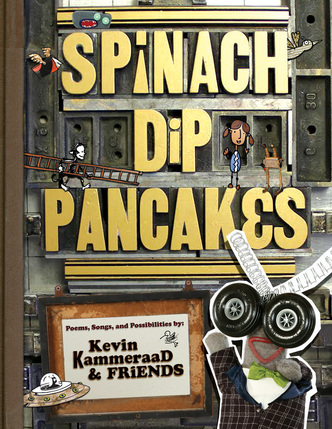

Spinach Dip Pancakes by Kevin Kammeraad, ill. Danny Adlerman, Kim Adlerman, Chris Fox, Alynn Guerra, Justin Haveman, Ryan Hipp, Stephanie Kammeraad, Carlos Kammeraad, Maria Kammeraad, Steve Kammeraad, Linda Kammeraad, Laurie Keller, Scott Mack, Ruth McNally Barshaw, Carolyn Stich, Joel Tanis, Corey Van Duinen, Aaron Zenz, & Rachel Zylstra

This book bears not a small number of similarities to the aforementioned Toucan Can book. The difference, however, is that these are all original little tiny poems put into a book illustrated by a huge range of different illustrators. The poems are funny and original and the art eclectic, weird, wise and wonderful. It even comes with a CD of performances of the poems. Want a taste? Then I am happy to premiere a video that is accompanying this book. The video cleverly brings to life the poem “Game”. I think you’ll get a kick out of it. And then be unable to remove it from your brain (good earworm, this).

If you liked that, check out the book’s book trailer and behind-the-scenes peek as well.

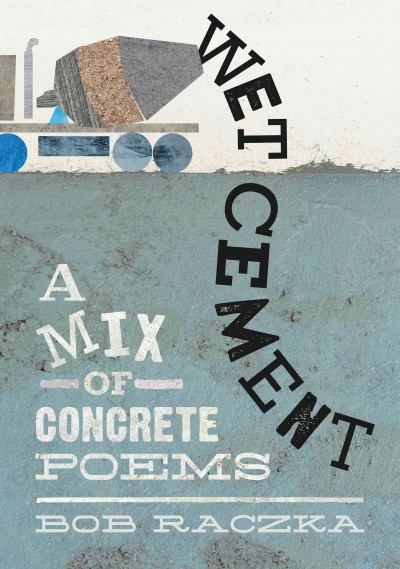

Wet Cement: A Mix of Concrete Poems by Bob Raczka

My year is not complete unless I am able to work a Raczka poetry collection onto a list. I’m very partial to this one. It’s a bit graphic design-y and a bit clever as all get out. Here’s my favorite poem of the lot:

Poetry is about taking away the words you don’t need

poetry is taking away words you don’t need

poetry is words you need

poetry is words

try

When Green Becomes Tomatoes: Poems for All Seasons by Julie Fogliano, ill. Julie Morstad

I think I broke more than a few hearts when I told people that Morstad’s Canadian status meant the book was ineligible for a Caldecott. At least you can take comfort in the fact that the poetry is sublime. I think we’ve all seen our fair share of seasonal poems. They’re not an original idea, yet Fogliano makes them seem new. This collection actually bears much in common with the poetry of the aforementioned Misuzu Kaneko. I think she would have liked it.

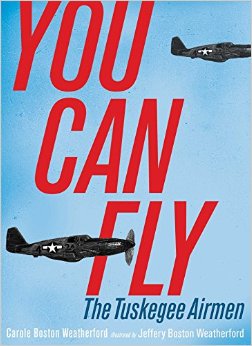

You Can Fly: The Tuskegee Airmen by Carole Boston Weatherford, ill. Jeffery Boston Weatherford

It’s poetry and a kind of verse novel as well. I figured I should include one in today’s list, though I’d argue that the verse here serves the poems better than the storyline. There is a storyline, of course, but I like the poetry for its own sake. My favorite in the book? The one about Lena Horne. I had no idea the personal sacrifices she made during WWII. There’s a picture book bio coming out about her in 2017, by the way. Looks like I’ll need to know more.

Interested in the other lists of the month? Here’s the schedule so that you can keep checking back:

December 1 – Board Books

December 2 – Board Book Adaptations

December 3 – Nursery Rhymes

December 4 – Picture Book Readalouds

December 5 – Rhyming Picture Books

December 6 – Alphabet Books

December 7 – Funny Picture Books

December 8 – Calde-Nots

December 9 – Picture Book Reprints

December 10 – Math Picture Books

December 11 – Bilingual Books

December 12 – International Imports

December 13 – Books with a Message

December 14 – Fabulous Photography

December 15 – Fairy Tales / Folktales

December 16 – Oddest Books of the Year

December 17 – Older Picture Books

December 18 – Easy Books

December 19 – Early Chapter Books

December 20 – Graphic Novels

December 21 – Poetry

December 22 – Fictionalized Nonfiction

December 23 – American History

December 24 – Science & Nature Books

December 25 – Transcendent Holiday Titles

December 26 – Unique Biographies

December 27 – Nonfiction Picture Books

December 28 – Nonfiction Chapter Books

December 29 – Novel Reprints

December 30 – Novels

December 31 – Picture Books

Joyce Sidman is one of my all-time favorite poets. Her books concentrate on the natural world and evoke beautiful images. Coupled with excellent illustrations, these poems are great for sharing with young readers, or for paging through with a cup of tea.

Sidman's latest effort, Before Morning, is illustrated by Beth Krommes!!! (Caldecott award winner, Beth Krommes, that is.)

I have this book on hold at my public library.

Check out Sidman's earlier book,

Winter Bees and Other Poems of the Cold. In it, Sidman, examines how various animals and insects survive through the cold months.

Doug Florian is an American poet/painter whose poetry books delight kids everywhere.

Winter Eyes is one of my favorite Florian titles. The words and pictures remind me of brisk cold skies and the coziness of winter sunsets. His palette is perfect.

Treasury of Christmas Stories. Edited by Ann McGovern. 1960. Scholastic. 152 pages. [Source: Bought]

Treasury of Christmas Stories was a delightful discovery for me, a true vintage find. The book was published in 1960, and it features stories and poems mainly published in the 1930's and 1940's. I liked that it was a blend of everything: fiction and nonfiction, stories and poems. I enjoyed the black and white illustrations as well. The illustrator is David Lockhart. Overall, both text and illustrations have a lovely, vintage feeling.

My top three poems would be, "Presents" by Marchette Chute, "Day Before Christmas" by Marchette Chute," and "A Visit from St. Nicholas" by Clement Clarke Moore. My top three stories would be: "A Piano by Christmas" by Paul Tulien, "Christmas Every Day" by W.D. Howells, and "A Miserable, Merry Christmas" by Lincoln Steffens.

Secret in the Barn by Anne Wood (poem)

It's nearly Christmas--it's Christmas Eve!

And it's snowing all over the place,

The roof of the barn is sugary white--

Its eaves are lined with lace.

A Christmas Gift for the General by Jeannette Covert Nolan (1937) (story)

Kennet, at the window, thought that the day was not at all like Christmas. The street he looked into was silent, almost desolate; the few people passing walked quickly with bent heads, as if they were cold, or sad--or both.

Christmas by Marchette Chute (1946) (poem)

My goodness, my goodness,

It's Christmas again.

The bells are all ringing.

I do not know when

I've been so excited.

The tree is all fixed,

The candles are lighted,

The pudding is mixed.

Christmas Every Day by W.D. Howells (story)

The little girl came into her papa's study, as she always did Saturday morning before breakfast, and asked for a story. He tried to beg off that morning, for he was very busy, but she would not let him. So he began: "Well, once there was a little pig--" She put her hand over his mouth and stopped him at the word. She said she had heard little pig stories till she was perfectly sick of them. "Well, what kind of story shall I tell, then?" "About Christmas. It's getting to be the season. It's past Thanksgiving already."

Ashes of the Christmas Tree by Yetza Gillespie (1946) (poem)

When Christmas trees at last are burned

Upon the hearth, they leap and flash

More brilliantly than other wood,

And wear a difference in the ash.

The Fir Tree by Hans Christian Anderson (story)

Once upon a time there was a pretty, green little Fir Tree. The sun shone on him; he had plenty of fresh air; and around him grew many large comrades, pines as well as firs. But the little Fir was not satisfied.

Presents by Marchette Chute (1932) (poem)

I wanted a rifle for Christmas,

I wanted a bat and a ball,

I wanted some skates and a bicycle,

But I didn't want mittens at all.

A Miserable, Merry Christmas by Lincoln Steffens (1931, 1935) (excerpt from an autobiography)

What interested me in our new neighborhood was not the school, nor the room I was to have in the house all to myself, but the stable which was built back of the house.

The Bells by Edgar Allan Poe (poem)

Hear the sledges with the bells--

Silver bells!

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

Yuletide Customs in Many Lands by Lou Crandall (1941) (nonfiction)

Christmas in May? It sounds strange, doesn't it? And yet in the early centuries of Christianity, the birthday of Jesus probably was sometimes celebrated in May, sometimes in other months; certainly it was often observed in January. This was because the exact date of the birth of Christ has never been known.

Lord Octopus Went to the Christmas Fair by Stella Mead (1934) (poem)

Lord Octopus went to the Christmas Fair;

An hour and a half he was traveling there.

Then he had to climb

For a weary time

To the slimy block

Of a sandstone rock,

And creep, creep away

To the big wide bay

Where a stout old whale

Held his Christmas Sale.

Christmas Tree by Aileen Fisher (1946) (poem)

I'll find me a spruce

in the cold white wood

with wide green boughs

and a snowy hood.

Silent Night, Holy Night (traditional song)

Deck the Halls (traditional song)

It Came Upon A Midnight Clear (traditional song)

O Christmas Tree (traditional song)

Wassail Song (traditional song)

The Birds (traditional song)

Shepherds, Shake Off Your Drowsy Sleep (traditional song)

The Jar of Rosemary by Maud Lindsay (excerpt from a book)

There was once a little prince whose mother, the queen, was sick. All summer she lay in bed, and everything was kept quiet in the palace; but when the autumn came she grew better.

One Night by Marchette Chute (1941) (poem)

Last winter when the snow was deep

And sparkled on the lawn

And there was moonlight everywhere,

I saw a little fawn.

Mr. Edwards Meets Santa Claus by Laura Ingalls Wilder (1935) (excerpt from a book)

The days were short and cold, the wind whistled sharply, but there was no snow.

Day Before Christmas by Marchette Chute (1941) (poem)

We have been helping with the cake

And licking out the pan,

And wrapping up our packages

As neatly as we can.

A Piano by Christmas by Paul Tulien (1957) (story)

There was one thing Billy's mother had been wanting, and that was a piano. Mother liked to play, and before her marriage she had played on her sister's piano every evening.

A Visit from St. Nicholas by Clement Clarke Moore (poem)

'Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there.

How Santa Claus Found the Poorhouse by Sophie Swett (1956) (story)

Heliogabalus was shoveling snow. The snow was very deep, and the path from the front door to the road was a long one, and the shovel was almost as big as Heliogabalus. But Gobaly--as everybody called him for short--didn't give up easily.

Golden Cobwebs by Rowena Bennett (poem)

The Christmas tree stood by the parlor door,

But the parlor door was locked

And the children could not get inside

Even though they knocked.

The Gift of St. Nicholas by Anne Malcolmson (1941) (story)

Three hundred years ago in the little city of New Amsterdam lived a young cobbler named Claas.

A New Song by Ernest Rhys (1946) (poem)

We will sing a new song

That sounds like the old:

Noel.

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

The Poetry Seven challenge this month was to write a poem on the theme of "sanctuary, rest, or seeking peace" inspired by the architectural art at one of Andi's favorite retreats, the Glencairn Museum Cloister in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

For further inspiration, I also found the Museum's mission statement, which "invites a diverse audience to engage with religious beliefs and practices, past and present, by exploring art, artifacts, and other cultural expressions of faith. By appealing to our common human endeavor to find meaning and purpose in our lives, we hope to foster empathy and build understanding among people of all beliefs, leading to positive social change through tolerance, compassion, and kindness."

Amen to that.

Here are some of the lovely photos of the Cloister that Andi sent us:

All exude peace, but I was drawn to the last photo above, the one with the two stone chairs facing each other. The more I looked at this image, the more I was overcome with a strong sense of longing because the chairs were empty.

Having no other plan (my usual approach!) I found myself addressing this longing on the page, by imagining the world as if these chairs were

not empty... and went on from there. Here is the poem that emerged:

If

another’s knees

were to sit across

from mine,

one of us might

drag a fingertip

along the window ledge

as if we were on

a train; one of us might

remark that the arches

—ah, bright arches—

form a heart; one of us

might know who poured

that concrete step;

one of us might lean

away from the chill

turning flesh to stone;

one of us might say:

sanctuary;

and the other

reply: I hear

the wheels must turn

ten thousand times.

We would talk as rams

and sheep do:

all about the grass

and how it feeds

the wide world.

---Sara Lewis Holmes (all rights reserved)

If you're curious about the Cloister,

you can read more here. And if you need more loveliness in your life, here are six other beautiful poems on "sanctuary, rest, or seeking peace" from each of my Poetry Sisters:

LizAndiKellyLauraTanitaTriciaPoetry Friday is hosted today by Bridget at

Wee Words for Wee Ones.

Another seasonal poem from the good folks at Harts Pass Comics. Enjoy!

Won Ton and Chopstick: A Cat and Dog Tale Told in Haiku. Lee Wardlaw. Illustrated by Eugene Yelchin. 2015. 40 pages. [Source: Library]

First sentence: It's a fine life, Boy. Nap, play, bathe, nap, eat, repeat. Practice makes purrfect.

Premise/plot: Won Ton returns in a second picture book in Won Ton and Chopstick. Won Ton is most upset--at least at first--at the new 'surprise' at his house. The surprise is a PUPPY. The family may call the puppy, "Chopstick," but Won Ton calls him PEST. This picture book has plenty of adventures for the pair.

My thoughts: I really loved Won Ton. And this second book is fun. I thought the repeating refrain of the first book was fun, but I think it's even better the second time around.

Puthimoutputhimoutputhimoutputhim--wait! I said him, not me!

That never gets old!!!

Text: 4 out of 5

Illustrations: 4 out of 5

Total: 8 out of 10

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By:

Cynthia Leitich Smith,

on 11/28/2016

Blog:

cynsations

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

poetry,

diversity,

middle grade fiction,

nonfiction,

ncte,

Melissa Sweet,

Marilyn Nelson,

Jason Reynolds,

awards,

Add a tag

By

NCTEfor

CynsationsATLANTA-- Authors Jason Reynolds, Melissa Sweet, and Marilyn Nelson were just announced winners of

prestigious literacy awards from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE).

Jason Reynolds won the 2017 Charlotte Huck Award for Outstanding Fiction for Children for his book

Ghost (Atheneum). The Charlotte Huck award is given to books that promote and recognize fiction that has the potential to transform children's lives.

Melissa Sweet won the 2017 Orbis Pictus Award for Outstanding Nonfiction for Children for her book

Some Writer!: The Story of E.B. White (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

The NCTE Orbis Pictus Award, established in 1989, is the oldest children's book award for nonfiction.

Marilyn Nelson won the 2017 NCTE Award for Excellence in Poetry for Children. The biannual award is given to a living American poet for his or her aggregate work for children ages 3–13.

Honor and Recommended book lists were also announced. All three authors will be invited to speak at next year's NCTE Annual Convention in St. Louis, MO.

NCTE is the nation's most comprehensive literacy organization, supporting teachers across the preK–college spectrum.

Through the expertise of its members, NCTE has served at the forefront of every major improvement in the teaching and learning of English and the language arts since 1911.

The assignment? A terza rima, the interlocking poetic form made famous by Dante's Inferno.

The theme? Gratitude.

For once, I knew instantly how this theme would inform my poem: There was no doubt its subject would be my poetry sisters, without whom I would not have explored poetry's "Here Be Dragons" waters. Without them, I'd still be stuck in my safe, shallow, shoals. (Or perhaps, if Dante were my guide, be marooned in poetry purgatory.) The only trick was putting all that into iambic pentameter in the rhyme scheme of a terza rima:

a

b

a

b

c

b

(repeat as necessary, and end with a couplet, if desired.)

In the end, my poem became a tribute to the poems The Poetry Seven tackled this year. Usually, I try to write to a wider audience, but this one is different. I know I'm a better writer when I write with friends---and I needed to say thank you, loud and clear.

(Links to my sister's Terza Rimas today can be found inside the poem.)

A Terza Rima for the Poetry Seven

Sisters do not let sisters ode alone

Nor do they, solo, rondeau redoublé

If raccontino calls, they hold the phone,

And bellow for some muse-y muscle; they

deep six, by stanza, surly sestinas

and dig a common grave for dross cliché.

Don’t bother asking for their subpoenas

To brashly bait expanding etheree

Nothing stops these pen-slinging tsarinas.

Once snagged, they let no villanelle go free;

Mouthy haiku in operating rooms

are re-lined and re-stitched, repeatedly;

So do not question who wears the pantoums

here; it’s seven sonnet-crowned, brave harpies:

Laura, Kel, Trish, Liz, Andi, T. : nom de plumes

who together with laptops (or Sharpies)

have danced the sedoka and triolet;

and ekprasticated art farandwee.

I’m grateful to wield words with this septet:

Friends, forever. Poetesses, well-met.

---Sara Lewis Holmes (all rights reserved)

Poetry Friday is hosted today by Laura at Writing the World for Kids.

Won Ton. Lee Wardlaw. Illustrated by Eugene Yelchin. 2011. 40 pages. [Source: Library]

First sentence: Nice place they got here. Bed. Bowl. Blankie. Just like home! Or so I've been told.

Premise/plot: Won-Ton (not his *real* name) is a shelter cat who's been adopted by a young boy. The book tells--in verse--what happens next. If you love cats, then this one is a real treat. For example:

Your tummy, soft as/ warm dough. I kneed and kneed, then/ bake it with a nap.

or

I explained it loud/ and clear. What part of "meow"/ don't you understand?

or

Sorry about the/ squish in your shoe. Must've/ been something I ate.

My thoughts: I do love cats. (Even though I'm allergic.) And this picture book alternates being cute and funny. I definitely enjoyed it.

Text: 4 out of 5

Illustrations: 4 out of 5

Total: 8 out of 10

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

Dawn again,

and I switch off the light.

On the table a tattered moth

shrugs its wings.

I agree.

Nothing is ever quite

what we expect it to be.

—Robert Dunn

Katherine Towler's deeply affecting and thoughtful portrait of Robert Dunn is subtitled "A Memoir of Place, Solitude, and Friendship". It's an accurate label, but one of the things that makes the book such a rewarding reading experience is that it's a memoir of struggles with place, solitude, and friendship — struggles that do not lead to a simple Hallmark card conclusion, but rather something far more complex. This is a story that could have been told superficially, sentimentally, and with cheap "messages" strewn like sugarcubes through its pages. Instead, it is a book that honors mysteries.

You are probably not familiar with the poetry of

Robert Dunn, nor even his name, unless you happen to live or have lived in or around Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Even then, you may not have noticed him. He was Portsmouth's second

poet laureate, and an important figure within the Portsmouth poetry scene from the late 1970s to his death in

2008. But he only published a handful of poems in literary journals, and his chapbooks were printed and distributed only locally — and when he sold them himself, he charged 1 cent. (Towler tells a story of trying to pay him more, which proved impossible.) He was insistently local, insistently uncommercial.

|

| Robert Dunn |

Dunn was also about as devoted to his writing as a person could be. When Towler met him in the early '90s, he lived in a single room in an old house, owned almost nothing, and made what little money he made from working part-time at the

Portsmouth Athenaeum. He seemed to live on cigarettes and coffee. When Towler first saw him around town, she, like probably many other people, thought he was homeless.

If a person could start a conversation with Dunn, which wasn't always easy, they would discover that he was very well read and eloquent. He was not, though, effusive, and he was deeply private. It was only late in his life, wracked with lung disease, that he opened up to anyone, and the person he seems to have opened up most to is Towler, though even then, she was able to learn very little about his past.

Towler got to know him because she was a neighbor, because she was intrigued by him, and because she was a writer on a different career track, with different ambitions. Dunn certainly wanted his poems to be read — he wouldn't have made chapbooks and sold them (even if only for a penny) if not — but he didn't want to subject himself to the quest-for-fame machine, he didn't want to do what everybody now says you must do if you want to have a successful writing career: become a "brand". He didn't bother with any sort of copyright, and Towler quotes a disclaimer from one of his books: "1983 and no nonsense about copyright. When I wrote these things they belonged to me. When you read them they belong to you. And perhaps one other." In 1999, he told a reporter from the

Boston Globe, "It just feels kind of silly posting no trespassing signs on my poems."

His motto, written on slips of paper he occasionally gave to people, was "Minor poets have more fun."

When Towler met him, she was struggling with writing a novel. She had lived peripatetically for a while, but had recently gotten married. She wanted to be published far and wide, and in her most honest moments she probably would have admitted that she would have liked to sell millions of copies of her books, get a great movie deal or two, get interviewed by Terry Gross and Charlie Rose, win a Pulitzer and a National Book Award and, heck, maybe even a Nobel. Success.

Once her first novel was published, Towler discovered what many people do in their first experiences with publication: It doesn't fill the hole. It is never enough. There are always other books selling better, getting more or better reviews, always other writers with more money and fame, and in American book culture these days, once a book is a month or two old, it's past its expiration date and rarely of much interest to booksellers, reviewers, or the public, because there's always something new, new, new to grab attention. You might as well sell your poems for a penny in Market Square.

By the time Towler's first novel is published, Portsmouth is deep in the process of gentrification. Not only have the local market, five-and-dime store, and hardware store been put out of business by rising rents and big box stores, but all seven of the downtown bookstores have disappeared. (Downtown is no longer bookstoreless. Bookstores, at least, can appeal to the gentrifiers, though it's still tough to be profitable with the cost of the rent what it is.) Towler gives a reading at a Barnes & Noble out at the mall, a perfect symbol of pretty much everything Robert Dunn had lived his life against: a mall, a chain bookstore. He attends the reading, though, and seems happy for Towler's success. He stands in line to get his book signed, and then says something that cuts Towler to the bone: "I'll let you get to your public."

As Robert turned away, leaving me to face a line of people waiting to have books signed, I felt that he had seen through me to the deep need for approval, the great strivings of ego, that lay at the heart of my desire to publish a book. Only by divorcing myself from the hunger for affirmation, his quip suggested, would I find what I truly desired. This is what he wanted for me, what he wanted for anyone who wrote.

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth continues to think through these ideas, and to work through the contrast between Dunn's fierce localism and solitude and Towler's own conflicting desires, hopes, dreams, and fears. She begins in great admiration of Dunn, who seems to have sacrificed absolutely everything to his writing and has somehow overcome any yearning for fame or reward. In that sense, he seems saintly.

But at what cost? This question is always in the background as Dunn becomes ill and more dependent on other people. If he wants to stay alive, the sort of solitude he cultivated and cherished is no longer possible, leading to some difficult confrontations and tensions.

Towler does her best not to impose her own values on Dunn's life, but she can't help wondering what it would be like to live as Dunn does. Though she sympathizes with him, and shares some of his ideals, she's no ascetic. She can't help but think of Dunn as lonely, since she would be, especially in illness. She cherishes her husband, she likes the house they buy together, she enjoys (at least sometimes) traveling to readings and leading writing workshops.

Dunn's life, as Towler presents it at least, shows the inadequacy of the question, "Are you happy?" In illness, Dunn was obviously not comfortable, and when he couldn't be at home, he was often not content. But happiness is a fleeting thing, not a state of being. Even if you believe that happiness is something that can be captured for more than a moment, there's no reason to think that, except for illness, Robert Dunn was

unhappy. He sculpted a life for himself that was, it seems, quite close to whatever life he might have desired having. I doubt having a life partner of some sort would have led to more moments of happiness for him, as Towler wonders at one point. The accommodations and annoyances of having another person around a lot of the time are insufferable for someone inclined toward solitude. Was this the case for Dunn? It's difficult to know, because he was difficult to know. Towler is remarkably restrained, I think, in not trying to impose her own pleasures on Dunn — she doesn't ever record saying to him what the partnered often say to the unpartnered, "Wouldn't you be happy with someone else in your life?" (I often think partnered people work a bit too hard to justify their own life choices, as if the presence of other types of lives are somehow an indictment of their own.) But even still, it does seem to be one of the more unbridgeable gulfs between types of people: the contentedly partnered seem as terrified of being unpartnered as the contentedly unpartnered are of being partnered, and so one looks on the other's life as a nightmare.

What

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth shows is the necessity of community. Robert Dunn was, for many reasons, lucky that he lived in Portsmouth when he did, because there was a real community of writers and people interested in writing and reading, and these people looked out for each other. Before the rents went whacko, it was possible to live in Portsmouth if you weren't rich. This is why the word

place in Towler's subtitle is so important. The book is not only a portrait of Robert Dunn, but a chronicle of the city that allowed him to be Robert Dunn. Towler is careful to chronicle the details of the place and community, both its people and its institutions. She shows the frustrations of dealing with bureaucracies of illness, and without being heavy-handed she depicts the ways that poverty is perceived in a place as ruggedly individualistic as New Hampshire — once she gets to know Robert Dunn, she also gets to see, feel, and struggle against the assumptions people who don't know him make. (In some of what she described him experiencing from nurses, doctors, and pharmacists, I couldn't help but think of my father, who did not have health insurance and who died of congestive heart failure. After he had a heart attack, he felt patronized and dismissed by hospitals that knew he couldn't pay his bills. Whether the hospital employees themselves actually felt this way, I don't know, but he perceived it deeply, and it contributed to his determination never to see another doctor or hospital. I'll forever remember the way his voice sounded when he told me, briefly, of this: the shattered pride, the humiliation, the rage all fraying his words.)

In its attention to the details of community — and a number of other ways —

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth makes a perfect companion to Samuel Delany's

Dark Reflections, another story of a poet, though in a very different environment. Arnold Hawley in Delany's novel is far less content than Robert Dunn in Towler's memoir, but their commitments are similar. Arnold is more seduced by the desire for fame and success than Dunn seems to have been, and so his personality is perhaps a bit more like Towler's, but without her relative success in everyday living. Having known Dunn, Towler is perhaps more capable of imagining Dunn as content in his life than Delany is quite able to imagine Arnold content — I've sometimes wondered whether Arnold is so tormented by his life because Delany himself would be tormented by that life, a life that is the opposite, in nearly every way, of his own. No matter. The books have much to say to (and with) each other.

There is much in Towler's memoir that is moving. She takes her time and doesn't rush the story. At first, I thought perhaps her pacing was unnecessarily slow, perhaps padding out what was a thin tale. I was wrong, though, because Towler is up to many things in the book, and needs her portrait of the place and person to be built carefully for her ideas and concerns to have resonance and real meaning. It's a tale of growing into knowledge and into something like intimacy, but also, at the same time, of coming to terms with unsolveable mysteries and uncrossable borders.

By the time I got to the fragmentary biography Towler offers as an appendix, those few pages were the most powerful of the book for me, because they show just how much we can't know. (I suppose the power was also one of some sort of personal recognition: Robert Dunn grew up only a dozen or so miles from where I grew up. The soil of his early years is as familiar to me as any other place on Earth. He was a graduate of the University of New Hampshire, where I finished my undergraduate degree and am now working on a Ph.D. I've only spent occasional time in Portsmouth, though enough over the decades to have seen some of the changes Towler writes about.) Primed by all the rest of Towler's story, it was this paragraph that most deeply affected me:

He went south in the summer of 1965 with the civil rights movement with a small group of Episcopalians from New Hampshire. Jonathan Daniels, who was shot and killed as he protected a young African-American woman attempting to enter a store in Hayneville, Alabama, had gone down ahead of the group. Robert would not talk about this experience, though others and I asked him about it directly. He did say once that he had known Daniels.

Had Towler rushed her story more, the resonances and mysteries in that paragraph wouldn't have been nearly as affecting. (It helps if you already know the story of Daniels, I suppose.)

The book ends with a delightful collection of what we might call "Robert Dunn's wit and wisdom", taken from various interviews and profiles in local papers that Dunn had stuck in a folder labeled "Vanity". Of the civil rights movement, he told Clare Kittredge of the

Boston Globe in 1999: "We had our hearts thoroughly broken."

Let's end these musings with what mattered most to Robert Dunn, though: the poetry. His poems remind me of

Frank O'Hara (whom he discusses with Towler) and

Samuel Menashe. They're colloquial and compressed, full of surprises. Thanks to Towler's book, I expect, Dunn's selected poems have finally been collected in

One of Us Is Lost, and a few are reprinted in

The Penny Poet. Here's one that seems particularly appropriate:

Public Notice

They've taken away the pigeon lady,

who used to scatter breadcrumbs from an old

brown hand and then do a little pigeon dance,

right there on the sidewalk, with a flashing

of purple socks. To the scandal of the

neighborhood. This is no world for pigeon

ladies.

There's a certain wild gentleness in

this world that holds it all together. And

there's a certain tame brutality that just

naturally tends to ruin and scatteration and

nothing left over. Between them it's a very

near thing. This is no world without pigeon

ladies.

Now world, I know you're almost

uglied out, but . . . just think! Try to

remember: What have you done with the

pigeon lady?

—Robert Dunn

Dawn again,

and I switch off the light.

On the table a tattered moth

shrugs its wings.

I agree.

Nothing is ever quite

what we expect it to be.

—Robert Dunn

Katherine Towler's deeply affecting and thoughtful portrait of Robert Dunn is subtitled "A Memoir of Place, Solitude, and Friendship". It's an accurate label, but one of the things that makes the book such a rewarding reading experience is that it's a memoir of struggles with place, solitude, and friendship — struggles that do not lead to a simple Hallmark card conclusion, but rather something far more complex. This is a story that could have been told superficially, sentimentally, and with cheap "messages" strewn like sugarcubes through its pages. Instead, it is a book that honors mysteries.

You are probably not familiar with the poetry of

Robert Dunn, nor even his name, unless you happen to live or have lived in or around Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Even then, you may not have noticed him. He was Portsmouth's second

poet laureate, and an important figure within the Portsmouth poetry scene from the late 1970s to his death in

2008. But he only published a handful of poems in literary journals, and his chapbooks were printed and distributed only locally — and when he sold them himself, he charged 1 cent. (Towler tells a story of trying to pay him more, which proved impossible.) He was insistently local, insistently uncommercial.

|

| Robert Dunn |

Dunn was also about as devoted to his writing as a person could be. When Towler met him in the early '90s, he lived in a single room in an old house, owned almost nothing, and made what little money he made from working part-time at the

Portsmouth Athenaeum. He seemed to live on cigarettes and coffee. When Towler first saw him around town, she, like probably many other people, thought he was homeless.

If a person could start a conversation with Dunn, which wasn't always easy, they would discover that he was very well read and eloquent. He was not, though, effusive, and he was deeply private. It was only late in his life, wracked with lung disease, that he opened up to anyone, and the person he seems to have opened up most to is Towler, though even then, she was able to learn very little about his past.

Towler got to know him because she was a neighbor, because she was intrigued by him, and because she was a writer on a different career track, with different ambitions. Dunn certainly wanted his poems to be read — he wouldn't have made chapbooks and sold them (even if only for a penny) if not — but he didn't want to subject himself to the quest-for-fame machine, he didn't want to do what everybody now says you must do if you want to have a successful writing career: become a "brand". He didn't bother with any sort of copyright, and Towler quotes a disclaimer from one of his books: "1983 and no nonsense about copyright. When I wrote these things they belonged to me. When you read them they belong to you. And perhaps one other." In 1999, he told a reporter from the

Boston Globe, "It just feels kind of silly posting no trespassing signs on my poems."

His motto, written on slips of paper he occasionally gave to people, was "Minor poets have more fun."

When Towler met him, she was struggling with writing a novel. She had lived peripatetically for a while, but had recently gotten married. She wanted to be published far and wide, and in her most honest moments she probably would have admitted that she would have liked to sell millions of copies of her books, get a great movie deal or two, get interviewed by Terry Gross and Charlie Rose, win a Pulitzer and a National Book Award and, heck, maybe even a Nobel. Success.

Once her first novel was published, Towler discovered what many people do in their first experiences with publication: It doesn't fill the hole. It is never enough. There are always other books selling better, getting more or better reviews, always other writers with more money and fame, and in American book culture these days, once a book is a month or two old, it's past its expiration date and rarely of much interest to booksellers, reviewers, or the public, because there's always something new, new, new to grab attention. You might as well sell your poems for a penny in Market Square.

By the time Towler's first novel is published, Portsmouth is deep in the process of gentrification. Not only have the local market, five-and-dime store, and hardware store been put out of business by rising rents and big box stores, but all seven of the downtown bookstores have disappeared. (Downtown is no longer bookstoreless. Bookstores, at least, can appeal to the gentrifiers, though it's still tough to be profitable with the cost of the rent what it is.) Towler gives a reading at a Barnes & Noble out at the mall, a perfect symbol of pretty much everything Robert Dunn had lived his life against: a mall, a chain bookstore. He attends the reading, though, and seems happy for Towler's success. He stands in line to get his book signed, and then says something that cuts Towler to the bone: "I'll let you get to your public."

As Robert turned away, leaving me to face a line of people waiting to have books signed, I felt that he had seen through me to the deep need for approval, the great strivings of ego, that lay at the heart of my desire to publish a book. Only by divorcing myself from the hunger for affirmation, his quip suggested, would I find what I truly desired. This is what he wanted for me, what he wanted for anyone who wrote.

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth continues to think through these ideas, and to work through the contrast between Dunn's fierce localism and solitude and Towler's own conflicting desires, hopes, dreams, and fears. She begins in great admiration of Dunn, who seems to have sacrificed absolutely everything to his writing and has somehow overcome any yearning for fame or reward. In that sense, he seems saintly.

But at what cost? This question is always in the background as Dunn becomes ill and more dependent on other people. If he wants to stay alive, the sort of solitude he cultivated and cherished is no longer possible, leading to some difficult confrontations and tensions.

Towler does her best not to impose her own values on Dunn's life, but she can't help wondering what it would be like to live as Dunn does. Though she sympathizes with him, and shares some of his ideals, she's no ascetic. She can't help but think of Dunn as lonely, since she would be, especially in illness. She cherishes her husband, she likes the house they buy together, she enjoys (at least sometimes) traveling to readings and leading writing workshops.

Dunn's life, as Towler presents it at least, shows the inadequacy of the question, "Are you happy?" In illness, Dunn was obviously not comfortable, and when he couldn't be at home, he was often not content. But happiness is a fleeting thing, not a state of being. Even if you believe that happiness is something that can be captured for more than a moment, there's no reason to think that, except for illness, Robert Dunn was

unhappy. He sculpted a life for himself that was, it seems, quite close to whatever life he might have desired having. I doubt having a life partner of some sort would have led to more moments of happiness for him, as Towler wonders at one point. The accommodations and annoyances of having another person around a lot of the time are insufferable for someone inclined toward solitude. Was this the case for Dunn? It's difficult to know, because he was difficult to know. Towler is remarkably restrained, I think, in not trying to impose her own pleasures on Dunn — she doesn't ever record saying to him what the partnered often say to the unpartnered, "Wouldn't you be happy with someone else in your life?" (I often think partnered people work a bit too hard to justify their own life choices, as if the presence of other types of lives are somehow an indictment of their own.) But even still, it does seem to be one of the more unbridgeable gulfs between types of people: the contentedly partnered seem as terrified of being unpartnered as the contentedly unpartnered are of being partnered, and so one looks on the other's life as a nightmare.

What

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth shows is the necessity of community. Robert Dunn was, for many reasons, lucky that he lived in Portsmouth when he did, because there was a real community of writers and people interested in writing and reading, and these people looked out for each other. Before the rents went whacko, it was possible to live in Portsmouth if you weren't rich. This is why the word

place in Towler's subtitle is so important. The book is not only a portrait of Robert Dunn, but a chronicle of the city that allowed him to be Robert Dunn. Towler is careful to chronicle the details of the place and community, both its people and its institutions. She shows the frustrations of dealing with bureaucracies of illness, and without being heavy-handed she depicts the ways that poverty is perceived in a place as ruggedly individualistic as New Hampshire — once she gets to know Robert Dunn, she also gets to see, feel, and struggle against the assumptions people who don't know him make. (In some of what she described him experiencing from nurses, doctors, and pharmacists, I couldn't help but think of my father, who did not have health insurance and who died of congestive heart failure. After he had a heart attack, he felt patronized and dismissed by hospitals that knew he couldn't pay his bills. Whether the hospital employees themselves actually felt this way, I don't know, but he perceived it deeply, and it contributed to his determination never to see another doctor or hospital. I'll forever remember the way his voice sounded when he told me, briefly, of this: the shattered pride, the humiliation, the rage all fraying his words.)

In its attention to the details of community — and a number of other ways —

The Penny Poet of Portsmouth makes a perfect companion to Samuel Delany's

Dark Reflections, another story of a poet, though in a very different environment. Arnold Hawley in Delany's novel is far less content than Robert Dunn in Towler's memoir, but their commitments are similar. Arnold is more seduced by the desire for fame and success than Dunn seems to have been, and so his personality is perhaps a bit more like Towler's, but without her relative success in everyday living. Having known Dunn, Towler is perhaps more capable of imagining Dunn as content in his life than Delany is quite able to imagine Arnold content — I've sometimes wondered whether Arnold is so tormented by his life because Delany himself would be tormented by that life, a life that is the opposite, in nearly every way, of his own. No matter. The books have much to say to (and with) each other.

There is much in Towler's memoir that is moving. She takes her time and doesn't rush the story. At first, I thought perhaps her pacing was unnecessarily slow, perhaps padding out what was a thin tale. I was wrong, though, because Towler is up to many things in the book, and needs her portrait of the place and person to be built carefully for her ideas and concerns to have resonance and real meaning. It's a tale of growing into knowledge and into something like intimacy, but also, at the same time, of coming to terms with unsolveable mysteries and uncrossable borders.

By the time I got to the fragmentary biography Towler offers as an appendix, those few pages were the most powerful of the book for me, because they show just how much we can't know. (I suppose the power was also one of some sort of personal recognition: Robert Dunn grew up only a dozen or so miles from where I grew up. The soil of his early years is as familiar to me as any other place on Earth. He was a graduate of the University of New Hampshire, where I finished my undergraduate degree and am now working on a Ph.D. I've only spent occasional time in Portsmouth, though enough over the decades to have seen some of the changes Towler writes about.) Primed by all the rest of Towler's story, it was this paragraph that most deeply affected me:

He went south in the summer of 1965 with the civil rights movement with a small group of Episcopalians from New Hampshire. Jonathan Daniels, who was shot and killed as he protected a young African-American woman attempting to enter a store in Hayneville, Alabama, had gone down ahead of the group. Robert would not talk about this experience, though others and I asked him about it directly. He did say once that he had known Daniels.

Had Towler rushed her story more, the resonances and mysteries in that paragraph wouldn't have been nearly as affecting. (It helps if you already know the story of Daniels, I suppose.)

The book ends with a delightful collection of what we might call "Robert Dunn's wit and wisdom", taken from various interviews and profiles in local papers that Dunn had stuck in a folder labeled "Vanity". Of the civil rights movement, he told Clare Kittredge of the

Boston Globe in 1999: "We had our hearts thoroughly broken."

Let's end these musings with what mattered most to Robert Dunn, though: the poetry. His poems remind me of

Frank O'Hara (whom he discusses with Towler) and

Samuel Menashe. They're colloquial and compressed, full of surprises. Thanks to Towler's book, I expect, Dunn's selected poems have finally been collected in

One of Us Is Lost, and a few are reprinted in

The Penny Poet. Here's one that seems particularly appropriate:

Public Notice

They've taken away the pigeon lady,

who used to scatter breadcrumbs from an old

brown hand and then do a little pigeon dance,

right there on the sidewalk, with a flashing

of purple socks. To the scandal of the

neighborhood. This is no world for pigeon

ladies.

There's a certain wild gentleness in

this world that holds it all together. And

there's a certain tame brutality that just

naturally tends to ruin and scatteration and

nothing left over. Between them it's a very

near thing. This is no world without pigeon

ladies.

Now world, I know you're almost

uglied out, but . . . just think! Try to

remember: What have you done with the

pigeon lady?

—Robert Dunn

What's An Apple? Marilyn Singer. Illustrated by Greg Pizzoli. 2016. Abrams. 24 pages. [Source: Review copy]

First sentence: What's an Apple? You can pick it. You can kick it. You can throw away the core. You can toss it. You can sauce it. You can roll it on the floor. You can wash it, try to squash it, or pretend that it's a ball. You can drink it. You can sink it. Give your teacher one this fall!

Premise/plot: Marilyn Singer has crafted a poem answering the question, "What's An Apple?" The text is simple and rhythmic. Plenty of rhymes to be found. It reads pretty effortlessly.

My thoughts: I do like this one more than What's A Banana? Perhaps in part because I LOVE apples and don't really like bananas. But also because I think some of the rhymes are just better in this one. I really like the 'You can smell it, caramel it' line. The books do complement one another.

Text: 4 out of 5

Illustrations: 3 out of 5

Total: 7 out of 10

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

What's A Banana? Marilyn Singer. Illustrated by Greg Pizzoli. 2016. Abrams. 24 pages. [Source: Review copy]

First sentence: What's a banana? You can grip it and unzip it. Smash and mash it with a spoon. You can trace it. Outer-space it--make believe that it's the moon.

Premise/plot: The whole book is a poem answering the question 'What's a Banana?'

My thoughts: Marilyn Singer writes poetry for children. Usually her books are collections of her poems. Not one poem stretched to cover an entire book. I have really enjoyed her work in the past, so I wanted to really like this one. I didn't quite. It was okay for me. I don't want my three minutes back or anything. I just wasn't wowed.

Text: 3 out of 5

Illustrations: 3 out of 5

Total: 6 out of 10

© 2016 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

|

Arlequin by by René de Saint-Marceaux

photographed at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Lyon, France,

by Kelly Ramsdell |

Who is that masked man? I thought I knew. I'd seen him before. Replicas of this statue are all over Amazon, ebay, and auction sites.

A version even appeared on The Antique Roadshow.

If you get a chance to watch that video, it gives some background on the original marble sculpture---which I cannot find images of online-- as well as info about the various bronze and plaster casts (in various sizes) that have been made from it, such as the one Kelly snapped a photo of in Lyon.

What I didn't know was how complicated the

history of the Arlequin (Harlequin) character was. For one thing, he began as a dark-faced devil character in French passion plays--yes, sadly, as another portrayal of a black man as a demon. His clothes were a slave's rags and patches before they evolved into a more orderly diamond pattern, and he was part of the tradition of blackface clowning in minstrel theater. I think his half mask may be the last remnant of that.

Much of that history is obscured, however, because the Harlequin also became a popular member of the zanni or comic servant characters in the Italian Commedia dell’Arte. There, his trope became one of a clever servant who thwarts his master...and courts his lady love with wit and panache. We might recognize bits of him today in our modern romantic hero.

So. That's a lot of stuff packed into one stock character. More than I could handle in one poem. In the end, I wrote what I saw reflected back in his eyes --- but I'm curious: how would you describe what YOU see in him?

ArlequinA stock character

takes stock of his life:

always tasked

by the master

always masked

from his true love

always asked

to repeat

the same lines.

—-and yet—

We never master

our taste for sharp

laughter;

we are unmasked

by it, we ask

with applause

for Love in tricked

out plaster, cast

marble to actor;

same lines;

new disaster.

----Sara Lewis Holmes (all rights reserved)

My poetry sisters all wrote about what they saw in our masked man. Find their poems here:

TriciaAndi (sitting this one out. See you next time, Andi!)

Poetry Friday is hosted today by Violet.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/5/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Misuzu Kaneko,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 poetry,

2016 picture book biographies,

David Jacobson,

Michiko Tsuboi,

Toshikado Hajiri,

Reviews,

poetry,

Best Books,

picture book biographies,

Sally Ito,

funny poetry,

middle grade poetry,

Add a tag

Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko

Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko

Narrative and Translation by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Michiko Tsuboi

Illustrated by Toshikado Hajiri

Chin Music Press

$19.50

ISBN: 9781634059626

Ages 5 and up

On shelves now

Recently I was at a conference celebrating the creators of different kinds of children’s books. During one of the panel discussions an author of a picture book biography of Fannie Lou Hamer said that part of the mission of children’s book authors is to break down “the canonical boundaries of biography”. I knew what she meant. A cursory glance at any school library or public library’s children’s room will show that most biographies go to pretty familiar names. It’s easy to forget how much we need biographies of interesting, obscure people who have done great things. Fortunately, at this conference, I had an ace up my sleeve. I knew perfectly well that one such book has just been published here in the States and it’s a game changer. Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko isn’t your typical dry as dust retelling of a life. It crackles with energy, mystery, tragedy, and, ultimately, redemption. This book doesn’t just break down the boundaries of biography. It breaks down the boundaries placed on children’s poetry, art, and translation too. Smarter and more beautiful than it has any right to be, this book challenges a variety of different biography/poetry conventions. The fact that it’s fun to read as well is just gravy.

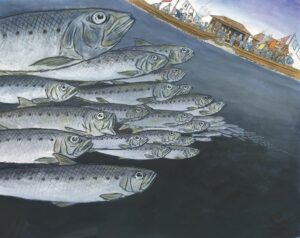

Part biography, part poetry collection, and part history, Are You an Echo? introduces readers to the life and work of celebrated Japanese poet Misuzu Kaneko. One day a man by the name of Setsuo Yazaki stumbled upon a poem called “Big Catch”. The poet’s seemingly effortless ability to empathize with the plight of fish inspired him to look into her other works. The problem? The only known book of her poems out there was caught in the conflagration following the firebombing of Tokyo during World War II. Still, Setsuo was determined and after sixteen years he located the poet’s younger brother who had her diaries, containing 512 of Misuzu’s poems. From this, Setsuo was able to piece together her life. Born in 1902, Misuzu Kaneko grew up in Senzaki in western Japan. She stayed in school at her mother’s insistence and worked in her mother’s bookstore. For fun she submitted some of her poems to a monthly magazine and shockingly every magazine she submitted them to accepted them. Yet all was not well for Misuzu. She had married poorly, contracted a disease from her unfaithful husband that caused her pain, and he had forced her to stop writing as well. Worst of all, when she threatened to leave he told her that their daughter’s custody would fall to him. Unable to see a way out of her problem, she ended her life at twenty-six, leaving her child in the care of her mother. Years passed, and the tsunami of 2011 took place. Misuzu’s poem “Are You an Echo?” was aired alongside public service announcements and it touched millions of people. Suddenly, Misuzu was the most famous children’s poet of Japan, giving people hope when they needed it. She will never be forgotten again. The book is spotted with ten poems throughout Misuzu’s story, and fifteen additional poems at the end.

There’s been a lot of talk in the children’s literature sphere about the role of picture book biographies. More specifically, what’s their purpose? Are they there simply to inform and delight or do they need to actually attempt to encapsulate the great moments in a person’s life, warts and all? If a picture book bio only selects a single moment out of someone’s life as a kind of example, can you still call it a biography? If you make up dialogue and imagine what might have happened in one scene or another, do those fictional elements keep it from the “Biography” section of your library or bookstore, or is there a place out there for fictionalized bios? These questions are new ones, just as the very existence of picture book biographies, in as great a quantity as we’re seeing them, is also new. One of the takeaways I’ve gotten from these conversations is that it is possible to tackle difficult subjects in a picture book bio, but it must be done naturally and for a good reason. So a story like Gary Golio’s Spirit Seeker can discuss John Coltrane’s drug abuse, as long as it serves the story and the character’s growth. On the flip side, Javaka Steptoe’s Radiant Child, a biography of Basquiat, makes the choice of discussing the artist’s mother’s fight with depression and mental illness, but eschews any mention of his own suicide.

There’s been a lot of talk in the children’s literature sphere about the role of picture book biographies. More specifically, what’s their purpose? Are they there simply to inform and delight or do they need to actually attempt to encapsulate the great moments in a person’s life, warts and all? If a picture book bio only selects a single moment out of someone’s life as a kind of example, can you still call it a biography? If you make up dialogue and imagine what might have happened in one scene or another, do those fictional elements keep it from the “Biography” section of your library or bookstore, or is there a place out there for fictionalized bios? These questions are new ones, just as the very existence of picture book biographies, in as great a quantity as we’re seeing them, is also new. One of the takeaways I’ve gotten from these conversations is that it is possible to tackle difficult subjects in a picture book bio, but it must be done naturally and for a good reason. So a story like Gary Golio’s Spirit Seeker can discuss John Coltrane’s drug abuse, as long as it serves the story and the character’s growth. On the flip side, Javaka Steptoe’s Radiant Child, a biography of Basquiat, makes the choice of discussing the artist’s mother’s fight with depression and mental illness, but eschews any mention of his own suicide.

Are You An Echo? is an interesting book to mention alongside these two other biographies because the story is partly about Misuzu Kaneko’s life, partly about how she was discovered as a poet, and partly a highlight of her poetry. But what author David Jacobson has opted to do here is tell the full story of her life. As such, this is one of the rare picture book bios I’ve seen to talk about suicide, and probably the only book of its kind I’ve ever seen to make even a passing reference to STDs. Both issues informed Kaneko’s life, depression, feelings of helplessness, and they contribute to her story. The STD is presented obliquely so that parents can choose or not choose to explain it to kids if they like. The suicide is less avoidable, so it’s told in a matter-of-fact manner that I really appreciated. Euphemisms, for the most part, are avoided. The text reads, “She was weak from illness and determined not to let her husband take their child. So she decided to end her life. She was only twenty-six years old.” That’s bleak but it tells you what you need to know and is honest to its subject.

But let’s just back up a second and acknowledge that this isn’t actually a picture book biography in the strictest sense of the term. Truthfully, this book is rife, RIFE, with poetry. As it turns out, it was the editorial decision to couple moments in Misuzu’s life with pertinent poems that gave the book its original feel. I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with a picture book biography of a poet that has done anything similar. I know one must exist out there, but I was hard pressed to think of it. Maybe it’s done so rarely because the publishers are afraid of where the book might end up. Do you catalog this book as poetry or as biography? Heck, you could catalog it in the Japanese history section and still be right on in your assessment. It’s possible that a book that melds so many genres together could only have been published in the 21st century, when the influx of graphic inspired children’s literature has promulgated. Whatever the case, reading this book you’re struck with the strong conviction that the book is as good as it is precisely because of this melding of genres. To give up this aspect of the book would be to weaken it.

But let’s just back up a second and acknowledge that this isn’t actually a picture book biography in the strictest sense of the term. Truthfully, this book is rife, RIFE, with poetry. As it turns out, it was the editorial decision to couple moments in Misuzu’s life with pertinent poems that gave the book its original feel. I’ve been wracking my brain, trying to come up with a picture book biography of a poet that has done anything similar. I know one must exist out there, but I was hard pressed to think of it. Maybe it’s done so rarely because the publishers are afraid of where the book might end up. Do you catalog this book as poetry or as biography? Heck, you could catalog it in the Japanese history section and still be right on in your assessment. It’s possible that a book that melds so many genres together could only have been published in the 21st century, when the influx of graphic inspired children’s literature has promulgated. Whatever the case, reading this book you’re struck with the strong conviction that the book is as good as it is precisely because of this melding of genres. To give up this aspect of the book would be to weaken it.

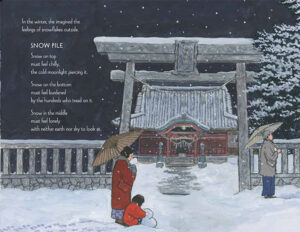

Right off the bat I was impressed by the choice of poems. The first one you encounter is called “Big Catch” and it tells about a village that has caught a great number of fish. The poem ends by saying, “On the beach, it’s like a festival / but in the sea they will hold funerals / for the tens of thousands dead.” The researcher Setsuo Yazaki was impressed by the poet’s empathy for the fish, and that empathy is repeated again and again in her poems. “Big Catch” is actually one of her bleaker works. Generally speaking, the poems look at the world through childlike eyes. “Wonder” contemplates small mysteries, in “Beautiful Town” the subject realizes that a memory isn’t from life but from a picture in a borrowed book, and “Snow Pile” contemplates how the snow on the bottom, the snow on the top, and the snow in the middle of a pile must feel when they’re all pressed together. The temptation would be to call Kaneko the Japanese Emily Dickenson, owing to the nature of the discovery of her poems posthumously, but that’s unfair to both Kaneko and Dickenson. Kenko’s poems are remarkable not just because of their original empathy, but also because they are singularly childlike. A kid would get a kick out of reading these poems. That’s no mean feat.

Mind you, we’re dealing with a translation here. And considering how beautifully these poems read, you might want a note from the translators talking about their process. You can imagine, then, how thrilled I was to find a half-page’s worth of a “Translators’ Note” explaining aspects of the work here that never would have occurred to me in a million years. The most interesting problem came down to culture. As Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi write, “In Japanese, girls have a particular way of speaking that is affectionate and endearing . . . However, English is limited in its capacity to convey Misuzu’s subtle feminine sensibility and the elegant nuances of her classical allusions. We therefore had to skillfully work our way through both languages, often producing several versions of a poem by discussing them on Skype and through extensive emails – Michiko from Japan, Sally from China – to arrive at the best possible translations in English.” It makes a reader really sit back and admire the sheer levels of dedication and hard work that go into a book of this sort. If you read this book and find that the poems strike you as singularly interesting and unique, you may now have to credit these dedicated translators as greatly as you do the original subject herself. We owe them a lot.

Mind you, we’re dealing with a translation here. And considering how beautifully these poems read, you might want a note from the translators talking about their process. You can imagine, then, how thrilled I was to find a half-page’s worth of a “Translators’ Note” explaining aspects of the work here that never would have occurred to me in a million years. The most interesting problem came down to culture. As Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi write, “In Japanese, girls have a particular way of speaking that is affectionate and endearing . . . However, English is limited in its capacity to convey Misuzu’s subtle feminine sensibility and the elegant nuances of her classical allusions. We therefore had to skillfully work our way through both languages, often producing several versions of a poem by discussing them on Skype and through extensive emails – Michiko from Japan, Sally from China – to arrive at the best possible translations in English.” It makes a reader really sit back and admire the sheer levels of dedication and hard work that go into a book of this sort. If you read this book and find that the poems strike you as singularly interesting and unique, you may now have to credit these dedicated translators as greatly as you do the original subject herself. We owe them a lot.

In the back of the book there is a note from the translators and a note from David Jacobson who wrote the text of the book that didn’t include the poetry. What’s conspicuously missing here is a note from the illustrator. That’s a real pity too since biographical information about artist Toshikado Hajiri is missing. Turns out, Toshikado is originally from Kyoto and now lives in Anan, Tokushima. Just a cursory glance at his art shows a mild manga influence. You can see it in the eyes of the characters and the ways in which Toshikado chooses to draw emotions. That said, this artist is capable of also conveying great and powerful moments of beauty in nature. The sunrise behind a beloved island, the crush of chaos following the tsunami, and a peach/coral/red sunset, with a grandmother and granddaughter silhouetted against its beauty. What Toshikado does here is match Misuzu’s poetry, note for note. The joyous moments she found in the world are conveyed visually, matching, if never exceeding or distracting from, her prowess. The end result is more moving than you might expect, particularly when he includes little human moments like Misuzu reading to her daughter on her lap or bathing her one last time.

Here is what I hope happens. I hope that someday soon, the name “Misuzu Kaneko” will become better known in the United States. I hope that we’ll start seeing collections of her poems here, illustrated by some of our top picture book artists. I hope that the fame that came to Kaneko after the 2011 tsunami will take place in America, without the aid of a national disaster. And I hope that every child that reads, or is read, one of her poems feels that little sense of empathy she conveyed so effortlessly in her life. I hope all of this, and I hope that people find this book. In many ways, this book is an example of what children’s poetry should strive to be. It tells the truth, but not the truth of adults attempting to impart wisdom upon their offspring. This is the truth that the children find on their own, but often do not bother to convey to the adults in their lives. Considering how much of this book concerns itself with being truthful about Misuzu’s own life and struggles, this conceit matches its subject matter to a tee. Beautiful, mesmerizing, necessary reading for one and all.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Misc: An article in PW about the translation.

I am on a technology roll lately! First Evernote and now Padlet. Check out the start of a new tool to inspire my students.

By:

Jalissa Corrie,

on 9/26/2016

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children's books,

Uncategorized,

poetry,

Diversity,

Race,

multicultural books,

Power of Words,

African/African American Interest,

author advice,

Educator Resources,

Dear Readers,

Teens/YA,

Diversity in YA,

Lee & Low Likes,

Diversity, Race, and Representation,

Book Lists by Topic,

Interviews with Authors and Illustrators,

Add a tag

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year! To recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today and hear from the authors and illustrators.

LEE & LOW BOOKS celebrates its 25th anniversary this year! To recognize how far the company has come, we are featuring one title a week to see how it is being used in classrooms today and hear from the authors and illustrators.

Today, we are celebrating Chess Rumble, which explores the ways this strategic game empowers young people with the skills they need to anticipate and calculate their moves through life.

Featured title: Chess Rumble

Author: G. Neri

Illustrator: Jesse Joshua Watson

Synopsis: In Marcus’s world, battles are fought everyday—on the street, at home, and in school. Angered by his sister’s death and his father’s absence, and pushed to the brink by a bullying classmate, Marcus fights back with his fists.