new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: dictionary, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 94

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: dictionary in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Catherine,

on 3/19/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

art,

Language,

competition,

pottery,

dictionary,

ceramics,

etymology,

British,

Linguistics,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

TV & Film,

oxfordwords,

OxfordWords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

The Great Pottery Throw Down,

Add a tag

The newest knockout competition on British television is The Great Pottery Throw Down (GPTD), in which an initial ten potters produce a variety of ceramic work each week, the most successful being declared Top Potter, and the least successful being ‘asked to leave’. The last four then compete in a final [...]

The post The Great Pottery Throw Down and language appeared first on OUPblog.

Stephen Wright wanted to become more learned, so he read the dictionary. He figured with all the words inside, it contained every book ever written.

I actually do read the dictionary sometimes--a page here and there. I love etymology.

The other day, I stared at the word, "disease," in a piece I was reading. Disease, disease, disease. Say any word over and over again, and it no longer sounds like a real word. I don't know why I fixate on these things, but I do!

DISEASE. Root word being EASE.

The qualifying prefix, "did," is the most powerful part of this word. DIS, according to Dictionary dot com is "a Latin prefix meaning 'apart,' 'asunder,' 'away,' utterly,'or having a privative, negative, or reversing force. Not being familiar with "privative," I also looked it up: "consisting in or characterized by the taking away, loss, or lack of something."

So DISEASE is characterized by the TAKING AWAY OF or the splitting asunder of FREEDOM from labor, pain, comfort; freedom from concern, anxiety, or solicitude; freedom from difficulty or great effort; freedom from stiffness or constraint.

No lecture or hidden meaning intended. I simply find amazing the power of words when we stop and truly consider their meanings.

By:

[email protected],

on 8/12/2015

Blog:

Perpetually Adolescent

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Book News,

humour,

Reference,

Education,

non-fiction,

language,

Dictionary,

Australian,

Lynne Truss,

Eats,

australian author,

Tracey Allen,

Australian writer,

Kate Burridge,

language evolution,

Shoots & Leaves,

Susan Butler,

Add a tag

Being a booklover and an avid reader, I occasionally enjoy reading and learning more about the English language. I’ve read some great books on the topic over the years and thought I’d share some of them with you below. Let’s start with two Australian books for those with a general interest in the origins and future direction of our […]

By: KatherineS,

on 6/15/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

India,

bamboo,

dictionary,

etymology,

OWC,

Oxford World's Classics,

British India,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

a. c. burnell,

henry yule,

Hobson-Jobson,

kate teltscher,

Add a tag

Early summer in London is heralded by the Chelsea Flower Show. This year, the winner of the Best Fresh Garden was the Dark Matter Garden, an extraordinary design by Howard Miller. Dark matter is invisible and thought to constitute much of the universe, but can only be observed through the distortion of light rays, an effect represented in the garden by a lattice of bent steel rods and lines of bamboo, swaying in the wind.

The post Bamboo Universe appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Connie Ngo,

on 12/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

slideshow,

oxford dictionary of quotations,

elizabeth knowles,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

Rhetoric & Quotations,

Dictionary of Quotations,

Books,

winter,

Christmas,

snow,

Quotes,

images,

quotations,

holiday,

dictionary,

Add a tag

Winter encourages a certain kind of idiosyncratic imagery not found during any other season: white, powdery snow, puffs of warm breath, be-scarfed holiday crowds. The following slideshow presents a lovely compilation of quotes from the eighth edition of our Oxford Dictionary of Quotations that will inspire a newfound love for winter, whether you’ve ever experienced snow or not!

Are there any other wintry quotes that you love? Let us know in the comments below.

Headline image credit: Winter bird. Photo by Mathias Erhart. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. All slideshow background images CC0/public domain via Pixabay or PublicDomainPictures.net (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10).

The post 10 quotes to inspire a love of winter appeared first on OUPblog.

By: RachelM,

on 2/19/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Religion,

Current Affairs,

oupblog,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

pope,

catholic church,

Pope Benedict XVI,

catholicism,

Humanities,

Benedict XVI,

*Featured,

vatican city,

abdicate,

Dictionary of Popes,

Papal resignation,

resign,

Add a tag

Pope Benedict XVI has led the Catholic Church since 2005, during a time of great change and difficulty. During his time as Pope, he rejected calls for a debate on the issue of clerical celibacy and reaffirmed the ban on Communion for divorced Catholics who remarry. He has also reaffirmed the Church’s strict positions on abortion, euthanasia, and gay partnerships. After eight years, Pope Benedict announced on Monday 11 February that he would step down as pontiff within two weeks. In his resignation statement the 85-year-old Pope said: “After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry.”

While abdication is not unheard of, it is the first papal resignation in almost 600 years. To give an overview of the history of papal resignations, we present selected entries from A Dictionary of Popes. (Full entries for the following Popes can be found on Oxford Reference.)

St Pontian (21 July 230–28 Sept. 235)

For most of his reign the Roman church enjoyed freedom from persecution as a result of the tolerant policies of Emperor Alexander Severus (222–35). Maximinus Thrax, however, acclaimed emperor in Mar. 235, abandoned toleration and singled out Christian leaders for attack. Among the first victims were Pontian and Hippolytus, who were both arrested and deported to Sardinia, the notorious ‘island of death’. Since deportation was normally for life and few survived it, Pontian abdicated (the first pope to do so), presumably to allow a successor to assume the leadership as soon as possible. He did so, according to the 4th-century Liberian Catalogue, on 28 Sept. 235, the first precisely recorded date in papal history (other apparently secure dates are based on inference).

St Marcellinus (30 June 296–?304; d. 25 Oct. 304)

On 23 Feb. 303, during St Marcellinus’s reign, Emperor Diocletian (284–305) issued his first persecuting edict ordering the destruction of churches, the surrender of sacred books, and the offering of sacrifice by those attending law-courts. Marcellinus complied and handed over copies of the Scriptures; he also, apparently, offered incense to the gods. His surrender of sacred books disqualified him from the priesthood, and if he was not actually deposed (as some scholars argue) he must have left the Roman church without an acknowledged head. The date of his abdication or deposition, however, is not known.

John XVII (16 May–6 Nov. 1003)

John XVII short-lived papacy is so obscure, the circumstances of his abdication, and indeed his death, are unknown.

Benedict IX (21 Oct. 1032–Sept. 1044; 10 Mar.–1 May 1045; 8 Nov. 1047–16 July 1048: d. 1055/6)

In 1032, Alberic III, head of the ruling Tusculan family, bribed the electorate and had his son Theophylact, elected as Pope, and the following day enthroned, with the style Benedict IX. Still a layman, he was not, as later gossip alleged, a lad of 10 or 12 but was probably in his late twenties; his personal life, even allowing for exaggerated reports, was scandalously violent and dissolute. If for twelve years he proved a competent pontiff, he owed this in part to native resourcefulness, but in part also to an able entourage and to the firm control which his father exercised over Rome. He was the only pope to hold office, at any rate de facto, for three separate spells.

St Peter Celestine V (5 July–13 Dec. 1294: d. 19 May 1296)

Naive and incompetent, and so ill educated that Italian had to be used in consistory instead of Latin, St Peter Celestine V let the day-to-day administration of the church fall into confusion.

Aware of his shortfalls, he considered handing over the government of the church to three cardinals, but the plan was sharply opposed. Finally, on 13 Dec. of the same year, he abdicated, was stripped off the papal insignia, and became once more ‘brother Pietro’.

And if you were wondering if there was any other way that a Pope could end their reign, the following Popes were deposed:

Liberius (17 May 352–24 Sept. 366)

A Roman by birth, he was elected at a time when the pro-Arian faction was in the ascendant in the east and Constantius II (337–61), now sole emperor, was taking steps to force the western episcopate to fall into line and join the east in anathematizing Athanasius of Alexandria (d. 373), always the symbol of Nicene orthodoxy.

Since Liberius held out against this, resisting bribery and then threats, he was brought by force to Milan and then, proving unyielding, banished to Beroea in Thrace (and, as such, deposed). Here his morale collapsed, overcome by boredom, said Jerome, and under pressure from the local bishop, and, in painful contrast to his previous resolute stand, after two years he acquiesced in Athanasius’ excommunication, accepted the ambiguous First Creed of Sirmium (which omitted the Nicene ‘one in being with the Father’), and made abject submission to the emperor.

With the death of Constantius (3 Nov. 361), however, he was free to reassume his role as champion of Nicene orthodoxy.

Gregory VI (1 May 1045–20 Dec. 1046: d. late 1047)

An elderly man respected in reforming circles, John Gratian (who became Gregory VI) was archpriest of St John at the Latin Gate when his godson Benedict IX (see above), recently restored to the papal throne, made out a deed of abdication in his favour on 1 May 1045. A huge sum of money apparently changed hands; and according to most sources Benedict sold the papal office, whilst according to others the Roman people had to be bribed. The whole transaction remains obscure, probably because it was deliberately kept dark at the time.

The bribery was ultimately unsuccessful, and on 20 Dec. the next year Gregory VI appeared before the synod of Sutri, near Rome. After the circumstances of his election had been investigated, the emperor and the synod pronounced him guilty of simony in obtaining the papal office, and deposed him.

Gregory XII (30 Nov. 1406–4 July 1415: d. 18 Oct. 1417)

In their eagerness to see the end of the Great Schism (1378–1417), each of the fourteen Roman cardinals at the conclave following Innocent VII’s death swore that, if elected, he would abdicate provided Antipope Benedict XIII did the same or should die.

At first it seemed that the hopes everywhere aroused by his election would be speedily fulfilled. However, Gregory’s attitude altered; personal doubts and fears, combined with pressures from quarters apprehensive of what might ensue if he had to resign, made him eventually refuse the planned meeting with Benedict XIII. As the negotiations dragged on, Gregory’s cardinals became increasingly restive. They joined forces with four of Benedict’s cardinals at Livorno, made a solemn agreement with them to establish the peace of the church by a general council, and in early July sent out with them a united summons for such a council to meet at Pisa in March 1409.

Both popes were invited to attend the forthcoming council, but both naturally refused. The council of Pisa duly met, under the presidency of the united college of cardinals, in the Duomo on 25 Mar. Charges of bad faith, and even of collusion, were laid in great detail against both popes. At the 15th session, on 5 June, Gregory and Benedict were both formally deposed as schismatics, obdurate heretics, and perjurors, and the holy seat was declared vacant. On 26 June the cardinals elected a new pope, Alexander V.

Adapted from multiple entries in A Dictionary of Popes, Second edition, by J N D Kelly and Michael Walsh, also available online as part of Oxford Reference. This fascinating dictionary gives concise accounts of every officially recognized pope in history, from St Peter to Pope Benedict XVI, as well as all of their irregularly elected rivals, the so-called antipopes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Papal resignations through the years appeared first on OUPblog.

By: RachelM,

on 11/30/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

douglas dunn,

harry lauder,

hugh macdiarmid,

j m barrie,

Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations,

norman mccraig,

roy williamson,

scottish quotations,

St Andrew's Day,

1942– scottish,

nbsp,

Literature,

quotations,

oupblog,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

scots,

quote,

scottish,

scotland,

sir walter scott,

odnb,

wordsmiths,

robert burns,

oxford dictionary of quotations,

Humanities,

bonnie,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

oxford dictionary of national biography,

robert crawford,

Add a tag

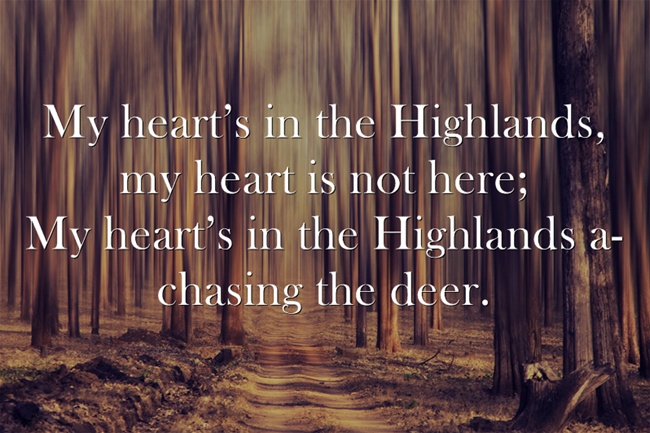

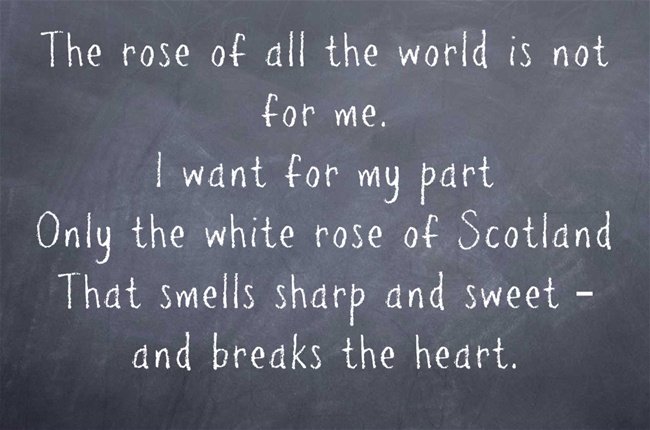

30 November is St Andrew’s Day, but who was St Andrew? The apostle and patron saint of Scotland, Andrew was a fisherman from Capernaum in Galilee. He is rather a mysterious figure, and you can read more about him in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. St Andrew’s Day is well-established and widely celebrated by Scots around the world. To mark the occasion, we have selected quotations from some of Scotland’s most treasured wordsmiths, using the bestselling Oxford Dictionary of Quotations and the Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.

There are few more impressive sights in the world than a Scotsman on the make.

J. M. Barrie 1860-1937 Scottish writer

From the lone shielding of the misty island

Mountains divide us, and the waste of seas –

Yet still the blood is strong, the heart is Highland,

And we in dreams behold the Hebrides!

John Galt 1779-1839 Scottish writer

O Caledonia! Stern and wild,

Meet nurse for a poetic child!

Sir Walter Scott 1771-1832 Scottish novelist

O flower of Scotland, when will we see your like again,

that fought and died for your wee bit hill and glen

and stood against him, proud Edward’s army,

and sent him homeward tae think again.

Roy Williamson 1936-90 Scottish folksinger and musician

I love a lassie, a bonnie, bonnie lassie,

She’s as pure as the lily in the dell.

She’s as sweet as the heather, the bonnie bloomin’ heather –

Mary, ma Scotch Bluebell.

Harry Lauder 1870-1950 Scottish music-hall entertainer

My poems should be Clyde-built, crude and sure,

With images of those dole-deployed

To honour the indomitable Reds,

Clydesiders of slant steel and angled cranes;

A poetry of nuts and bolts, born, bred,

Embattled by the Clyde, tight and impure.

Douglas Dunn 1942– Scottish poet

Who owns this landscape?

The millionaire who bought it or

the poacher staggering downhill in the early morning

with a deer on his back?

Norman McCaig 1910–96 Scottish poet

The Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations fifth edition was published in October this year and is edited by Susan Ratcliffe. The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations seventh edition was published in 2009 to celebrate its 70th year. The ODQ is edited by Elizabeth Knowles.

The Oxford DNB online has made the above-linked lives free to access for a limited time. The ODNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,000 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 130 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, etymology, and dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about the Little Oxford Dictionary of Quotations on the

View more about the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations on the

A pile of final book art has been looming large of late. Spring "break" is thusly oxymoronic over at Erik Brooks Illustration for the entire month of April. A fitting launch for my 5th decade? Lordy Pete... Enjoy your Sudoku!

By: Nicola,

on 9/21/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

spin,

english usage,

language history,

lynda mugglestone,

word trends,

‘spin’,

mugglestone,

lynda,

‘emancipation’,

spinmeister,

bowler,

words,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

oed,

dictionary,

definition,

Add a tag

By Lynda Mugglestone

Spin is one of those words which could perhaps now do with a bit of ‘spin’ in its own right. From its beginnings in the idea of honest labour and toil (in terms of etymology, spin descends from the spinning of fabric or thread), it has come to suggest the twisting of words rather than fibres – a verbal untrustworthiness intended to deceive and disguise. Often associated with newspapers and politicians, to use spin is to manipulate meaning, to twist truth for particular ends – usually with the aim of persuading readers or listeners that things are other than they are.

By: Lauren,

on 9/1/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

back to school,

new words,

Merriam-Webster,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

added to the dictionary,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

It's back to school, and that means it's time for dictionaries to trot out their annual lists of new words. Dictionary-maker Merriam-Webster released a list of 150 words just added to its New Collegiate Dictionary for 2011, including "cougar," a middle-aged woman seeking a romantic relationship with a younger man, "boomerang child," a young adult who returns to live at home for financial reasons, and "social media" -- if you don't know what that means, then you're still living in the last century.

By: Lauren,

on 6/27/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Constitution,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

supreme court,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Law & Politics,

chief justice,

courtroom,

John G. Roberts Jr.,

legal terms,

justices,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

The Supreme Court is using dictionaries to interpret the Constitution. Both conservative justices, who believe the Constitution means today exactly what the Framers meant in the 18th century, and liberal ones, who see the Constitution as a living, breathing document changing with the times, are turning to dictionaries more than ever to interpret our laws: a new report shows that the justices have looked up almost 300 words or phrases in the past decade. Earlier this month, according to the New York Times, Chief Justice Roberts consulted five dictionaries for a single case.

Even though judicial dictionary look-ups are on the rise, the Court has never commented on how or why dictionary definitions play a role in Constitutional decisions. That’s further complicated by the fact that dictionaries aren’t designed to be legal authorities, or even authorities on language, though many people, including the justices of the Supreme Court, think of them that way. What dictionaries are, instead, are records of how some speakers and writers have used words. Dictionaries don’t include all the words there are, and except for an occasional usage note, they don’t tell us what to do with the words they do record. Although we often say, “The dictionary says…,” there are many dictionaries, and they don’t always agree.

As for the justices, they aren’t just looking up technical terms like battery, lien, and prima facie, words which any lawyer should know by heart. They’re also checking ordinary words like also, if, now, and even ambiguous. One of the words Chief Justice Roberts looked up last week in a patent case was of. These are words whose meanings even the average person might consider beyond dispute.

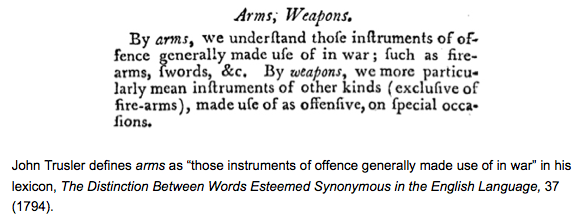

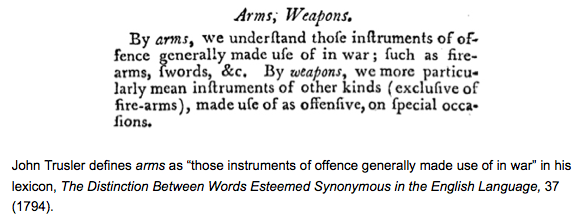

Sometimes dictionary definitions inform landmark decisions. In Washington, DC, v. Heller (2008), the case in which the high Court decided the meaning of the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, both Justice Scalia and Justice Stevens checked the dictionary definition of arms. Along with the dictionaries of Samuel Johnson and Noah Webster, Justice Scalia cited Timothy Cunningham’s New and Complete Law Dictionary (1771), where arms is defined as “any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another” (variations on this definition occur in English legal texts going back to the 16th century). And Justice Stevens cited both Samuel Johnson’s definition of arms as “weapons of offence, or armour of defence” (1755) and John Trusler’s “by arms, we understand those instruments of offence generally made use of in war; such as firearms, swords, &c.” (1794).

The much less publicized case of Barnhart v. Peabody Coal Co. (2003) turned in part on the meaning of a single word, shall. In this case the justices all agreed that the word shall in one particular section of the federal Coal Act functions as a command. What they disagreed about was just how much latitude the use of shall permits.

In Peabody Coal the Court’s majority decided that s

By: Lauren,

on 5/18/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

essex,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

German,

word origins,

onomatopoeia,

dictionary,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Scandinavian,

norwegian,

word history,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

larrup,

lunker,

you big lunk,

lunker,

Add a tag

(The first word was larrup.)

By Anatoly Liberman

Lunker seems to be well-known in the United States and very little in British English. Mark Twain used lunkhead “blockhead.” Lunker surfaced in books later, but lunkhead must have been preceded by lunk, whatever it meant. In today’s American English, lunker has several unappetizing and gross connotations, and we will let them be: one cannot constantly deal with turd and genitals. Only two senses bear upon etymological discussion: “a very big object” and “big game fish.” From the meager facts at my disposal I am apt to conclude that “big fish” is secondary, so that the word hardly arose in the lingo of fishermen. Also, lunkhead probably alluded to someone with a big head “typical of an idiot,” as they used to say.

In dictionaries I was able to find only one conjecture on the origin of lunker. The Random House Unabridged Dictionary (RHD) suggested that it might be a blend of lump and hunk. Unless we know for certain that a word is a blend (cf. smog, brunch, motel, blog, gliberal, Eurasia, Tolstoevsky, and the like), it is impossible to prove that some lexical unit is the product of merger: for instance, squirm is perhaps a blend of squirt and worm but perhaps not. I suspect that RHD’s idea was suggested by The Century Dictionary, which, although it offers no derivation of lunkhead and does not list lunker, refers under lummox “an unwieldy, clumsy, stupid fellow” (“probably ultimately connected with lump”) to British dialectal lummakin “heavy; awkward.” Lump turned up first only in Middle English. It has numerous cognates in Dutch, German, and the Scandinavian languages and seems to have developed from the basic meaning “a shapeless mass.” No impassable barrier separates lunk- from lump-, for n and m constantly alternate in roots, and final -p and -k are also good partners (see the previous post). German Lumpen means “rag,” and a rag may be understood as a shapeless mass or something hanging loose. It is the semantics that complicates our search for the etymology of lunker: we need cognates that mean “a big thing,” and they refuse to appear. Lump does provide a clue to the history of lunker; by contrast, hump may be left out of the picture: we have enough trouble without it.

Joseph Wright included lunkered (not lunker!) in The English Dialect Dictionary, but without specifying his sources or saying, as he often did: “Not known to our informants.” His definition is curt: “(of hair) tangled; Lincolnshire.” He also cited several other similar northern (English and Scots) words, of which especially instructive are lunk “heave up and down (as a ship); walk with a quick uneven, rolling motion; limp” and lunkie “a hole left for the admission of animals.” Unlike larrup, discussed in the previous post, lunker did find its way into my database. A single citation occurs in The Essex Review for 1936. The Reverend W. J. Pressey quotes a 1622 entry in a diary: “Absent from Church, and for ‘lunkering’ a poor woman’s house in great Sampford, to the great fear and terror of the said poor woman.” He comments:

“This word is derived from the Scandinavian. ‘Lunkere

By: Lauren,

on 5/11/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

language,

bible,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

oed,

dictionary,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

tit,

American English,

*Featured,

notes and queries,

Lexicography & Language,

regional english,

Bibliography of English Etymology,

larrup,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

For this essay I have to thank Walter Turner, who asked me about the origin of larrup. The verb means “beat, thrash, whip, flog.” Long before my database became available in printed form as A Bibliography of English Etymology, I described in a special post what kind of lexical fish my small-meshed net had caught. (Sorry for the florid style. I remember a dean saying in irritation to one of the speakers at the Assembly: “Can you stop speaking in metaphors?” I mean that our team read a lot of articles and marked the places where anything pertaining to etymology turned up, without missing even the most trivial remarks.) After some of the words had been gathered in a mini-thesaurus, I observed with surprise the number of synonyms for “beat, strike.” Baist, bansel, clat, dozz, keb, lase, polch, starn, and what not. Needless to say, my knowledge of the language and of the ways of the world did not go beyond bang, buffet, lick, trounce, whack, and the like. And let me repeat: the database includes only such words about whose origin something has been said in the articles I have read, so, by definition, a small fraction of the existing literature. Later in Notes and Queries an exchange titled “Provincialisms for ‘To Thrash’” came my way, with mump, clool, wheang, and more of the same enriching my passive vocabulary. Among other things, in elementary school “‘thimble-pie’ was a serious letting down. It was administered with the dame’s thimble finger,” and (the author adds), “as I remember, was very much past a joke.” All the northern correspondents knew skelp, but no one mentioned larrup, though, according to Joseph Wright’s The English Dialect Dictionary, it is recognized in every part of England. It is also widespread in the United States, even if less so (see Dictionary of American Regional English). What then is its etymology? Larrup does not occur in my database, which means that I have not run into a single article or note in which its history is mentioned. And yet, as happens so often in etymological studies, its origin was, if not explained, at least elucidated, almost a century ago; only no one has paid attention.

The OED lists larrup (the earliest citation there goes back to 1823) but offers no etymology. It only quotes an 1825 publication, in which lirrop (not larrup) “to beat” is followed by a short remark: “This is said to be a corruption of the sea term, lee-rope.” Larrop and lirrop, as pointed out in the OED, are, naturally, variants of larrup. As to lee-rope, we need not bother about this exercise in folk etymology. The Century Dictionary also has an entry on larrup and says: “Prob. [from] D[utch] larpen, thresh with the flails; cf. larp, a lash. The E[nglish] form larrup (for *larp) may represent the strongly rolled r of the D[utch]: so larum, alarum, for alarm” (in linguistic works, an asterisk before a form means that it has not been attested). This statement can be found verbatim in several later dictionaries. From time to time I write about “unsung heroes of etymology.” Charles P. G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary, is one of them. He can always be relied upon; yet I do not know where he found the words larp and larpen. The Great

By: Lauren,

on 3/30/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Old English,

modern english,

monthly gleanings,

english literature,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

learning english,

misspelling,

teetotal,

Reference,

words,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

word origins,

spelling,

dictionary,

anatoly liberman,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Question: How large is an average fluent speaker’s vocabulary?

Answer: I have often heard this question, including its variant: “Is it true that English contains more words than any other (European) language?” The problem is that “an average fluent speaker” does not exist. Also, it is important to distinguish between how many words we recognize (our so-called passive vocabulary) and how many we use in everyday communication (active vocabulary). The size of people’s active vocabulary depends on their needs, but it is rarely large. Thus, five-year olds can say everything they want, but if they are read to and if grownups speak to them all the time, they understand complicated tales and the content of their parents’ conversation amazingly well (oftentimes much better than one could wish for). Some people cultivate their conversational skills and make an effort to use “sophisticated” words in their dealings with the outside world; others are happy to remain at the level of first-graders. One of the most memorable events in my teaching career happened about thirty years ago when a student approached me after a lecture and, having complimented me (they always do in such cases), added: “But I don’t understand half of the words you use.” Ever since that day I have worked systematically on reducing my “public” vocabulary but sometimes still forget myself.

Our passive vocabulary depends on our reading habits. Since “great classics” are being frowned upon as elitist, the younger generation has trouble understanding even 19th-century English (Jane Austen, Dickens, Thackeray, and so on, through Henry James and the utterly forgotten Galsworthy), while publishers promote books written more or less in Basic English. Students get tired of following those authors’ synonyms, idioms, and convoluted syntax (their greatest compliments are matter of fact and down to earth, while all digressions are castigated as rambling). The same is true, to an even greater extent, of their attempts to read Defoe, Fielding, and Swift. For some Americans of college age even the vocabulary of Mark Twain poses difficulties. It is hard to believe that Mark Twain, like Jack London and Charles Dickens, was self-taught. Yet quite a few of our best and brilliantly educated writers did not make use of an extensive vocabulary. Oscar Wilde is a typical example. Others, like Dickens and Meredith, let alone James Joyce, made a heroic effort to use as many rare and learned words as possible.

Good dictionaries of English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Swedish, etc. seem to be equally thick. In a dictionary containing about 60,000 words one can find practically everything one needs. Webster’s Unabridged features seven or eight times more. Obviously, none of us needs to know so much. But perhaps two features distinguish English from its neighbors: an overabundance of synonyms (because of the partly unhealthy influx of Romance words) and the ubiquity of slang. French also overflows with argot, but English dictionaries of slang (British, American, Canadian, Australian) are almost unbelievably thick. This makes it harder to master current English than, for example, German, but each language has its difficulties. English resorts to all the usual international words (music, radio, antibiotic, and the like), while Icelandic prefers native coinages for such concepts. It appears that whether you want to learn a foreign language or your own you have to make a sustained effort. But then this is what the sweat of one’s brow is for. Only Adam had an easy life: none of the objects around him had a name, and he was instructed to call them something (presumably he remembered his own neologisms). His offspring ca

By: HannaO,

on 2/24/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

words,

Dictionaries,

chesterfield,

dictionary,

Samuel Johnson,

voltaire,

elizabeth knowles,

how to read a word,

knowles,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

lord chesterfield,

dictionarium,

algeo,

malfi,

misquotations,

1754,

duchess,

Add a tag

We have lots of dictionaries here at Oxford. (Here are just a few.) Yet I had never given much thought to the word “dictionary” itself until I read Elizabeth Knowles new book How to Read a Word. In the following excerpt, Knowles offers a short history of the dictionary, with thoughts from logophiles like Samuel Johnson on the authority of these books of words. –Hanna Oldsman, Publicity Intern

‘Is it in the dictionary?’ is a formulation suggesting that there is a single lexical authority: ‘The Dictionary’. As the British academic Rosamund Moon has commented, ‘The dictionary most cited in such cases is the UAD: the Unidentified Authorizing Dictionary, usually referred to as “the dictionary”, but very occasionally as “my dictionary”.’ The American scholar John Algeo has coined the term lexicographicolatry for a reverence for dictionary authority amounting to idolatry. As he explained:

English speakers have adopted two great icons of culture: the Bible and the dictionary. As the Bible is the sacred Book, so the dictionary has become the secular Book, the source of authority, the model of behavior, and the symbol of unity in language.

–John Algeo ‘Dictionaries as seen by the Educated Public in Great Britain and the USA’ in F.J. Hausmann et al. (eds.) An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography (1989) vol. 1, p. 29

While recognizing the respect for lexical authority illuminated by this passage, it is difficult to find less unquestioning perspectives. The notion of any dictionary representing a type of scriptural authority runs counter, for instance, to the view of the ‘Great Lexicographer’ Samuel Johnson that:

Dictionaries are like watches, the worst is better than none, and the best cannot be expected to go quite true.

–Samuel Johnson, letter to Francesco Sastres, 21 August 1984

A dictionary may also be highly derivative: twenty years before Johnson’s letter, the French writer and critic Voltaire had warned cynically in his Philosophical Dictionary that ‘All dictionaries are made from dictionaries.’ However, there is evidence that Johnson’s contemporary

0 Comments on Words, words, words as of 1/1/1900

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast

A good limerick’s no trouble to fashion:

Avoid lines that are metrically clashin’,

Bring together some rhymes,

Build in humor at times,

And enjoy it. For some, it’s a passion!

That’s by Jesse Frankovich and from a website called The Omnificent English Dictionary In Limerick Form.

Of course the poetry form called limerick takes its name from the Irish city called Limerick. The style of rhyme was around before it was named that though.

Edward Lear who invented such imaginary things as runcible spoons is also credited with popularizing, if not inventing limericks.

That said, Lear was dead before limericks are documented as having been called limericks. He passed away in 1888 and The Oxford English Dictionary traces the first time such poetry being called a limerick to 1896.

The reason limericks began being called limericks was that these often nonsensical poems became a kind of party game. The party goers would take turns—and the dictionaries tell me that each participant not only had to make up a limerick on the spot, but they had to sing it too—following which the chorus ran “Will you come up to Limerick?”Presumably directed at the next person who had to perform.

The reason limericks began being called limericks was that these often nonsensical poems became a kind of party game. The party goers would take turns—and the dictionaries tell me that each participant not only had to make up a limerick on the spot, but they had to sing it too—following which the chorus ran “Will you come up to Limerick?”Presumably directed at the next person who had to perform.

This makes me think that “coming up to Limerick” sort of parallels “coming up with a limerick” although I’m sure it isn’t quite that literal.

The place Limerick itself is said to have had this or a similar name for more than 1400 years and according to both Patrick Joyce in The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places and Adrian Room in Placenames of the World the meaning of the name is “a bare piece of land.” This could have meant somewhere that wasn’t forested but it could also have meant a place that was hard to defend militarily.

Five days a week Charles Hodgson produces

Podictionary – the podcast for word lovers, Thursday episodes here at OUPblog. He’s also the author of several books including his latest

History of Wine Words – An Intoxicating Dictionary of Etymology from the Vineyard, Glass, and Bottle.

It’s become an ever-popular post, my Publishing Dictionary. This is the third version I’ve done. Some of the words and definitions remain the same, but at your requests there have been a number of additions. For those who have been regular readers of the blog, I apologize for the repetition. But just like any good dictionary, we need updates, and here is the New and Updated Publishing Dictionary.

AAR: The Association of Authors’ Representatives is an organization of literary and dramatic agents that sets certain guidelines and standards that professional and reputable agents must abide by. It is really the only organization for literary agents of its kind.

Advance: The amount the publisher pays up front to an author before the book is published. The advance is an advance on all future earnings.

ARCs: Advance Review Copies. Not the final book, these are advance and unfinalized copies of the book that are sent to reviewers.

Auction: During the sale of a manuscript to publishers sometimes, oftentimes if you’re lucky, you’ll have an auction. Not unlike an eBay auction, this is when multiple publishers bid on your book, and ultimately, the last man standing wins (that’s the one who offers the most lucrative deal).

BEA: BookExpo America is the largest book rights fair in the United States. This is where publishers from all over the world gather to share rights information, sell book rights, and flaunt their new, upcoming titles.

Blurb: A one-paragraph (or so) description of your book. People often compare a blurb to back cover copy, and while it’s similar, it’s frequently more streamlined and focuses on the heart and the chief conflict in the story. This is the pitch you use in your query letter as well as the pitch you would use in pitch appointments.

Book proposal: The author’s sales pitch for her book. A good book proposal is used to introduce agents and editors to your book and show them not only why it’s a book they need and want for their lists, but also how well you’ll be able to pull it off.

Category or Category Romance: “Category” is the shortened term often used to refer to category romances. These are romances typically, and almost exclusively, published by Harlequin/Silhouette in their lines. Examples of category books are published in Silhouette Desire, Harlequin Superromance, or Silhouette Special Edition. Note that not all Harlequin/Silhouette imprints are considered category.

Commercial Fiction: Fiction written to appeal to a large or mass market audience. Commercial fiction typically includes genres like mystery, romance, science fiction and fantasy. Popular commercial fiction writers include Nora Roberts, John Grisham, and James Patterson.

Commission: The percentage of your earnings paid to your agent, typically 15%.

Copy Edits: Edits that focus on the mechanics of your writing. A copy editor typically looks for grammar, punctuation, spelling, typos, and style.

Cover copy: The term used to describe all of the wording and description on the front and back cover of your book.

Cover Letter: This is the letter that should accompany any material you send to an agent or an editor. A cover letter should remind the agent that the material has been requested, where you met if you’ve met, and of course the same information that is in your query letter—title, genre, a short yet enticing blurb of your book, and bio information if you have any. This can often be interchanged with Query Letter.

Credentials: What make you qualified to write a book and knowledgeable in your field of expertise. Credentials are usually defined by your level of education and experience on the job.

Editor: The person who buys on behalf of the publishing house. While jobs differ from house to house, typically the acquisitions editor is your primary

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast

I heard a woman talking about an old ski cabin she used to rent. She said it was ramshackled.

I heard a woman talking about an old ski cabin she used to rent. She said it was ramshackled.

I wondered how a male goat (a ram) secured to something (shackled) might mean, in The Oxford English Dictionary’s words “loose and shaky, as if ready to fall to pieces; rickety, tumbledown; in a state of severe disrepair.”

Goats and shackles don’t play into the etymology of this word at all.

Like too many words that sound so delicious the etymology of ramshackle is a little unclear.

People started calling tumbledown buildings ramshackle a little less than 200 years ago.

For 100 years before that it had been ramshackled.

Etymology dictionaries of the time speculated that it was built on a Scottish prefix ram which was an intensifier, and shauchle, another possibly Scottish word that had first meant to “shuffle your feet” but then later meant to “wear out” your shoes by shuffling your feet.

Thus ram shauchle would mean “really worn out.”

But the timing of the appearance of these component words in the written record seems to make this assembly unlikely.

Ramshackled was already in fairly common use before the shoe worn shauchle appeared at all.

So it was back to the etymological drawing board.

The more recent theory is that houses that are called ramshackle are called that because that’s what they look like after they are ransacked.

This etymology has the advantage that the word ransacked is historically related to houses or buildings and not shoes and ramshackle similarly applies to buildings.

Five days a week Charles Hodgson produces

Podictionary – the podcast for word lovers, Thursday episodes here at OUPblog. He’s also the author of several books including his latest

History of Wine Words – An Intoxicating Dictionary of Etymology from the Vineyard, Glass, and Bottle.

By Anatoly Liberman

Some time ago I received a question about the origin of pun. Since an answer to it would have taken up all the space I have for my monthly gleanings, I decided to devote a special post to this word. Our correspondent noticed that pun and pundit appeared in English at nearly the same time, that a pun “heaps together” different meanings (so Skeat), while the root of pundit (Sanskrit for “learned man”) also means “to heap, pile up.” Moreover, bunk “berth” may likewise go back to a word for “heap.” Is it possible that pundit and bunk provide a clue to the origin of pun? We had a nice email exchange about bunk in etymology, but I left the answer for the blog, to heighten the questioner’s suspense.

According to a popular notion, the aim of etymology is to discover the roots from which words sprout. This belief leads to setting up sound complexes that are endowed with a rather vague or even abstract meaning and are responsible for the emergence of siblings across a broad spectrum of languages. It is usually forgotten that the reconstructed roots never had an independent existence. True, the authors of older works believed in a stage of pure roots in the history of Indo-European, but this stage is a mirage, a vision of virile and highly potent stubs. To discover the origin of a word, one should know the social environment in which it was coined and its earliest meaning. Even if for the sake of argument we agree that the root pun- “heap” never lost its grip on speakers’ minds (or their Freudian-Jungian subconscious), why should it have produced the English word pun in the middle of the 18th century, millennia after it gave birth to Sanskrit pundit and long after the appearance of the putative Scandinavian etymon of bunk?

The date of the earliest citation of pun given in the first edition of the OED is 1669. Now a 1644 example is known. The word seems to have emerged some time around 1640. This date tallies with the fact that Abraham Cowley’s comedy The Guardian (acted 1641) has a character Mr. Puny described as “a young Gallant, a pretender to Wit.” In the revised version of the play (1661), the adjective Punish occurs, with reference to that gentleman’s kind of wit. Cowley does not use the word pun, and we do not know how the name and the adjective were pronounced. On paper, Puny and Punish look like puny “tiny” and the verb punish respectively. Both must have had punning connotations. Names of this type were popular in Cowley’s days. For instance, Goldsmith and Sheridan have Mr. Slang (unfortunately, no lines are assigned to him) and Mr. Fag (fag “servant”). 18th-century dictionaries feature pun, which they define as quibble, witty conceit, fancy, and clench. “Play on words” was also mentioned regularly, but the original connotation of pun seems to have been “an over-subtle distinction” (this is what clench, a side-form of clinch means), rather than what we today understand by it. In any case, the heaping up of meanings need not have been its initial sense. So let us forget bunk (with its possible etymon bunker), and see what pundits say on the subject.

From the outset, two forms have competed in attempts to etymologize pun: French pointe and Engl. pun “to pound,” the latter from Old Engl. punian (none of my references antedates 1730, the year Nathaniel Bailey’s dictionary was published). But alongside those two, numerous wild conjectures abounded. Among the suggested sources of

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast

I recently listened to a podcast from BBC History Magazine in which Neil MacGregor, Director of The British Museum talked about world history.

To paraphrase, he said that in today’s world a Eurocentric view of history is out of place. A measure of that is an exhibit they’ve worked on in which a British viewpoint is the exception rather than the rule.

I think the word geisha also illustrates this changing approach to the study of history; in this case word history.

The Oxford English Dictionary is currently in the middle of revising the dictionary for the Third Edition. Many entries available at the OED online have been brought up to date, but many others have not.

Geisha is one that has not.

Geisha is one that has not.

Consequently the entry for geisha has as its most recent example citation a quoted dated 1947.

This date is relevant since geisha is a Japanese word and 1947 is only two years after the atomic bombing of Japan and its World War II surrender.

One might not be surprised to find that a dictionary definition of this vintage omits a Japanese viewpoint. Such is indeed the case with the OED Second Edition.

The etymology of geisha there is said simply to be “Japanese” and the definition reads “A Japanese girl whose profession is to entertain men by dancing and singing; loosely, a Japanese prostitute.”

I checked the OED definition for prostitute which had been updated as of June 2007 and I wasn’t surprised to find that prostitutes are expected to do more than dance and sing in their professional capacity.

Other dictionaries delve a little deeper into the etymology of geisha and in so doing expose a little more sensitive treatment of what a geisha might be.

Some break the word geisha in two explaining it as “art person.”

This sits better against the definition of a professional singer and dancer.

The Century Dictionary goes a little further saying geisha is built on words that were once Chinese: the gei means “polite accomplishments” and originally came from a Chinese word ki meaning “an art” or “a profession”; the sha ending conferring a meaning of “one who does” the art.

Five days a week Charles Hodgson produces

Podictionary – the podcast for word lovers, Thursday episodes here at OUPblog. He’s also the author of several books including his latest

History of Wine Words – An Intoxicating Dictionary of Etymology from the Vineyard, Glass, and Bottle.

iTunes users can subscribe to this podcast

When I hear the word chauvinist I think of a person—male—who takes a superior view of the capabilities of his gender. I guess I’m influenced by the 1970s phrase male chauvinist pig that evolved out of the woman’s lib movement.

When I hear the word chauvinist I think of a person—male—who takes a superior view of the capabilities of his gender. I guess I’m influenced by the 1970s phrase male chauvinist pig that evolved out of the woman’s lib movement.

Dictionaries take a wider perspective and offer examples of chauvinists who think it is their country that is innately superior.

Chauvinist and chauvinism are words that demonstrate the power of the entertainment industry.

Chauvinist is a word that arose because of the over-the-top antics of Nicholas Chauvin.

The story goes that Nicholas Chauvin was a soldier in Napoleon’s army and was mad-crazy enthusiastic about fighting for his country and his leader. He sustained war wounds on 17 different occasions, lost fingers, had his face disfigured and still kept up his rah-rah attitude. Napoleon was so happy to have such a keen supporter that Nicholas Chauvin was given a ceremonial sword and a cash prize.

But eventually Napoleon himself fell out of favor and Nicholas Chauvin’s excessive enthusiasm began to earn him only ridicule.

At least two plays were written in the early 1800s that featured him as an over-zealous wing-nut. Through these plays people in France and then elsewhere began using his name to describe people who had an unreasonable superiority complex about their own social group—with particular emphasis on nationalism and militarism.

His name became so famous through theses plays and the adoption of the term chauvinism that people actually began to believe that he had been a real person.

I say this because in 1993 Gerard de Puymège went looking for authentic military records about Nicholas Chauvin and wrote a book about the fact that the guy had never really existed; he was just a creation of the theatre.

Five days a week Charles Hodgson produces

Podictionary – the podcast for word lovers, Thursday episodes here at OUPblog. He’s also the author of several books including his latest

History of Wine Words – An Intoxicating Dictionary of Etymology from the Vineyard, Glass, and Bottle.

When I hear the word chauvinist I think of a person—male—who takes a superior view of the capabilities of his gender. I guess I’m influenced by the 1970s phrase male chauvinist pig that evolved out of the woman’s lib movement.

When I hear the word chauvinist I think of a person—male—who takes a superior view of the capabilities of his gender. I guess I’m influenced by the 1970s phrase male chauvinist pig that evolved out of the woman’s lib movement.

Thanks for putting this together, this is a great resource!

Wow! Thanks so much, Jessica! You always go above and beyond. :-) Great info...

It seems it may vary in different parts of the industry, but to this publicity drone, "blurb" is synonymous with "endorsement," i.e., a quote from a person of some renown saying how awesome the book is and that everyone should run out and buy it immediately.

This is fantastic! Thanks so much Jessica. :)

Thank you for taking the time to post your New and Updated Publishing Dictionary. It's very helpful!

This is great. You should put a permanent link to this in your sidebar (make it the top entry)!

An excellent resource.

May I suggest you add "single title" since you covered "category."

this is brilliant and I'm really pleased that I actually knew what they all meant. 6 months ago I'd never heard of a query, I had no idea that was how things worked. Thanks to your blog and others I feel I'm in a much better position to try and publish (when I'm ready) than I would have been back then!

Jessica, thanks for this! I've also heard "blurb" the way Lin described, but that seems to be in line with the first sentence of your definition. I'm bookmarking this!

This is such a handy resource. Thanks so much :)

Godsend!

What about Quality Trade Paperback--aren't those the larger-sized versions, usually retailing for

$13.-$15.??