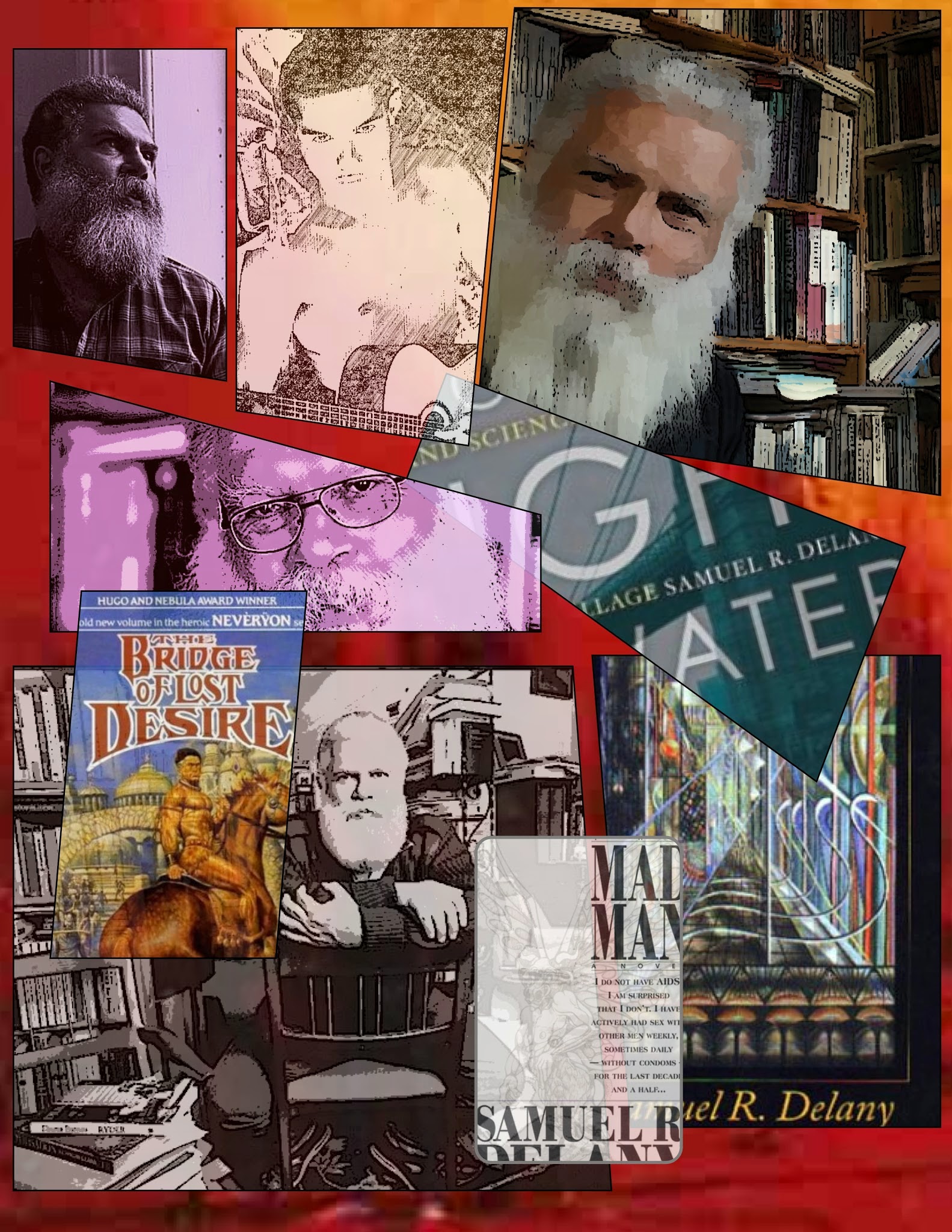

Kenneth James is editing the journals of Samuel Delany for publication.

Volume 1 is coming out from Wesleyan University Press in December. For the future volumes, Ken needs help with funding.

If you already know how valuable this project is, don't read on. Just go donate.But if you need some convincing, please read on...

“Mesmerizing . . . a true portrait of an artist as a young Black man . . . already visible in these pages are the wit, sensitivity, penetration, playfulness and the incandescent intelligence that will characterize Delany and his extraordinary work.”

—Junot Díaz, author of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

“This is a tremendously significant and vital addition to the oeuvre of Samuel Delany; it clarifies questions not only of the writer’s process, but also his development—to see, in his juvenilia, traces that take full form in his novels—is literally breathtaking.”

—Matthew Cheney, author of Blood: Stories

“These journals give us the very rare experience of being able to watch genius escaping from the chrysalis.”

—Jo Walton, author of Among Others

As my blurb in the publicity materials shows, I've read volume 1, which covers the years 1957-1969. It's great. It shows us the very young Delany, it offers juvenilia and drafts that have never been public before, it shows his reading and writing and thinking during the period where he went from being a precocious kid to a professional writer. It's thoughtfully, sensitively edited, and is being published by the academic press that has been most devoted to Delany for a few decades now. It's a revelatory book.

Volume 2 will be even more exciting, I expect. Ken plans for it to begin with

Dhalgren material and then to continue through the 1970s, which would mean it includes material related to

Trouble on Triton, Tales of Nevèrÿon, and, depending on how he edits it,

Hogg, Neveryóna, Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, and others. It will also show how deeply connected Delany's nonfiction is to his fiction, and will show the development of his engagement with critical theory. Additionally, there's lots of material in the 1970s journals about his first experiences as a university teacher.

I'm just back from spending a few days at the

Delany archive at Boston University, and I've looked through a few of the 1970s journals. They're truly thrilling for anybody interested not only in Delany the writer, but in the writing and thinking process in general. They're especially interesting for those of us who think that after 1969, Delany's work only got more brilliant. They are working journals, not really diaries as we generally think of them, and they clarify a lot of questions of when particular things were written, and why, and how. That makes them, if nothing else, of immense scholarly value. But they've also got material in them that just flat-out makes for good reading.

The work of editing them is ... daunting. This is why Kenneth James deserves your donations. (Wesleyan University Press is great, but they've got limited funding themselves. These books are not going to sell millions of copies, not because people don't love Delany's work, but because there's a small market for this sort of publication.) Ken probably knows Delany's work as well as anybody on the planet other than (perhaps) SRD himself. As a Cornell undergraduate, he interviewed Delany in 1986 — an interview deemed substantial enough to be included in

Silent Interviews. Later, he wrote the introductions to

Longer Views and

1984: Selected Letters. He organized the SUNY Buffalo conference on Delany, the first international conference on SRD's work, and guest-edited the volume of

Annals of Scholarship that preserved some of the papers from that conference. He's written on various of Delany's books. He knows his stuff better than perhaps anybody else knows that stuff.

Ken is an independent scholar without a permanent university affiliation, which in this economic/academic structure means he has hardly any source of financial support for a project like this. He needs our support. Editing these journals is a full-time job if it's going to get done before the end of the century. The journals are handwritten, mostly in spiral ring notebooks. They're in various states of organization and disorganization. (The BU archivists are magnificent, and have done a great job of indexing and preserving the journals to the best of their ability, but these were working journals, not documents immediately designed for eternal preservation) And they are

copious. In six hours of reading and notetaking yesterday, I made it through only a few months' worth of journals. Transcribing, editing, and annotating them will be a gargantuan task. Ken has already proved it is a task he is prepared for, a task he is capable of completing. I don't think I could do it. I know he can.

I could go on and on. Delany is one of the most important writers and thinkers of our time. The more I read, the more I delve into his archive, the more I believe this to be true. I've spent a decade studying his work and feel I'm only now beginning to move beyond a superficial appreciation of it.

We need these books, and we need Ken to be the one to put them together. There is nobody better for the job.

Please help him do it.

This term, I taught an American literature survey for the first time since I was a high school teacher, and since the demands of a college curriculum and schedule are quite different from those of a high school curriculum and schedule, it was a very new course for me. Indeed, I've never even

taken such a course, as I was successful at avoiding all general surveys when I was an undergrad.

As someone who dislikes the

nationalism endemic to the academic discipline of literature, I had a difficult time figuring out exactly what sort of approach to take to this course — American Literature 1865-present — when it was assigned to me. I wanted the course to be useful for students as they work their way toward other courses, but I didn't want to promote and strengthen the assumptions that separate literatures by national borders and promote it through nationalistic ideologies.

I decided that the best approach I could take would be to highlight the forces of canonicity and nationalism, to put the question of "American literature" at the forefront of the course. This would help with another problem endemic to surveys: that there is far more material available than can be covered in 15 weeks. The question of what we should read would become the substance of the course.

The first choice I made was to assign the appropriate volumes of the

Norton Anthology of American Literature, not because it has the best selection, but because it is the most powerfully canonizing anthology for the discipline. Though the American canon of literature is not a list, the table of contents of the

Norton Anthology is about as close as we can get to having that canon as a definable, concrete object.

Then I wanted to add a work that was highly influential and well known but also not part of the general, academic canon of American literature — something for contrast. For that, I picked

A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs in the

Library of America edition, which has an excellent, thorough introduction by Junot Díaz. I also wanted the students to see how critical writings can bolster canonicity, and so I added

The Red Badge of Courage in

the Norton Critical Edition. Next, I wanted something that would puzzle the students more, something not yet canonized but perhaps with the possibility of one day being so, and for that I chose

Wild Seed by Octavia Butler (who is rapidly becoming an academic mainstay, particularly with her novel

Kindred). Finally, I thought the Norton anthology's selection of plays was terrible, so I added Suzan-Lori Parks's

Red Letter Plays, which are both in direct dialogue with the American literary canon and throwing a grenade at it.

The result was

this syllabus. As with any first time teaching a course, I threw a lot against the wall to see what might stick. Overall, it worked pretty well, though if I teach the course again, I will change quite a bit.

The students seemed to like the idea of canonicity and exploring it, perhaps because half of them are English Teaching majors who may one day be arbiters of the canon in their own classrooms. Thinking about why we read what we read, and how we form opinions about the respectability of certain texts over others, was something they seemed to enjoy, and something most hadn't had a lot of opportunity to do in a classroom setting before.

Starting the course with three articles we could return to throughout the term was one of the best choices I made, and the three all worked well: Katha Pollitt's “Why We Read: Canon to the Right of Me” from

The Nation and

Reasonable Creatures; George E. Haggerty's

“The Gay Canon” from

American Literary History; and Arthur Krystal's

“What We Lose If We Lose the Canon” from

The Chronicle of Higher Education. We had to spend some real time working through the ideas in these essays, but they were excellent touchstones in that they each offered quite a different view of the canon and canonicity.

I structured the course in basically two halves: the first half was mostly prescriptive on my part: read this, this, and this and talk about it in class. It was a way to build up a common vocabulary, a common set of references. But the second half of the course was much more open. The group project, in which students researched and proposed a unit for an anthology of American literature of their own, worked particularly well because it forced them to make choices in ways they haven't had to make choices before, and to see the difficulty of it all. (One group that said their anthology unit was going to emphasize "diversity" ended up with a short story section of white men plus Zora Neale Hurston. "How are you defining diversity for this section?" I asked. They were befuddled. It was a good moment because it highlighted for them how easy it is to perpetuate the status quo if you don't pay close attention and actively try to work against that status quo [assuming that working against the status quo is what you want to do. I certainly didn't require it. They could've said their anthology was designed to uphold white supremacy; instead, they said their goal was to be diverse, by which they meant they wanted to include works by women and people of color.])

Originally, there were quite a few days at the end of the term listed on the schedule as TBA. We lost some of these because we had three classes cancelled for snow in the first half of the term, and I had to push a few things back. But there was still a bit of room for some choice of what to read at the end, even if my grand vision of the students discovering things through the group project that they'd like to spend more time on in class didn't quite pan out. I should have actually built that into the group project: Choose one thing from your anthology unit to assign to the whole class for one of our TBA days. The schedule just didn't work out, though, and so I fell back on asking for suggestions, which inevitably led to people saying they were happy to read anything but poetry. (They

hate poetry, despite all my best efforts to show them how wonderful poetry can be. The poetry sections were uniformly the weakest parts of the proposed anthology units, and class discussions of even the most straightforward poems are painfully difficult. I love teaching poetry, so this makes me terribly sad. Next time I teach this course, I'm building even more poetry into it! Bwahahahahaaaa!) A couple of students are big fans of popular postmodernist writers (especially David Foster Wallace), so they wanted to make sure we read Pynchon's "Entropy" before the course ended, and we're doing that for our last day.

Though they haven't turned in their term papers, I've read their proposals, and it's interesting to see what captured their interest. Though we read around through a bunch of different things in the Norton anthology, at least half of the students are gravitating toward

Red Badge of Courage, Wild Seed, or

The Red Letter Plays. They have some great topics, but I was surprised to see that most didn't want to go farther afield, or to dig into one of the areas of the Norton that we hadn't spent much time on. Partly, this is probably the calculus of getting work done at the end of the term: go with what you are not only most interested in, but most confident you know what the person grading your paper thinks about the thing you're writing about. I suppose I could have required that their paper be about something we haven't read for class, but at the same time, I feel like we flew through everything and there's tons more to be discussed and investigated in any of the texts. They've come up with good topics and are doing good research on them all, so I'm really not going to complain.

In the future, I might be tempted to cut

Wild Seed, even though the students liked it a lot, and it's a book I enjoy teaching. It just didn't fit closely enough into our discussions of canonicity to be worth spending the amount of time we spent on it, and in a course like this, with such a broad span of material and such a short amount of time to fit it all in, the readings should be ruthlessly focused. It would have been better to do the sort of "canon bootcamp" that Crane and Burroughs allowed and then apply the ideas we learned through those discussions to a bunch of different materials in the Norton. We did that to some extent, but with the snow days we got really off kilter. I especially wish we'd had more time to discuss two movements in particular: the Harlem Renaissance and Modernism. Each got one day, and that wasn't nearly enough. My hope was that the groups would investigate those movements (and others) more fully for their anthology projects, but they didn't.

One of our final readings was Delany's

"Inside and Outside the Canon", which is dense and difficult for undergrads but well worth the time and effort. In fact, I'd be tempted to do it a week or so earlier if possible, because we needed time to apply some of its ideas more fully before students plunged into the term paper. I wonder, in fact, if it would be better as an ending to the first half of the course than the second... In any case, it's a keeper, but definitely needs time for discussion and working through.

If I teach the course again, I would certainly keep the Crane/Burroughs pairing. It worked beautifully, since the similarities and differences between the books, and between the writers of those books, were fruitful for discussion, and the Díaz intro to

Princess of Mars is a gold mine. We could have benefitted from one more day with each book, in fact, since there was so much to talk about: constructions of masculinity, race, heroism; literary style; "realism"...

I would be tempted to add a graphic narrative of some sort to the course. The Norton anthology includes a few pages from

Maus, but I would want a complete work. I'd need to think for a while about exactly what would be effective, but including comics of some sort would add another interesting twist to questions of canonicity and "literature".

Would I stick with the question of canonicity as a lens for a survey class in the future? Definitely. It's open enough to allow all sorts of ways of structuring the course, but it's focused enough to give some sense of coherence to a survey that could otherwise feel like a bunch of random texts strung together in chronological order for no apparent reason other than having been written by people somehow associated with the area of the planet currently called the United States of America.

Recently, Locus published an online discussion of the work of Samuel R. Delany with a bunch of different writers and critics, primarily aimed at discussing Delany’s status as the newly-crowned Grand Master of the Science Fiction Writers of America. Plenty of interesting things are said there, and the participants include a number of people I’m very fond of (both as writers and people), but the particular focus ended up, I thought, creating a certain narrowness to the discussion, especially regarding the post-Dhalgren works, and I thought it might be nice to gather a different group of people together to discuss Delany … differently.So here we are. I put out the call to a wide variety of folks, and this is the group that responded. We used a Google Doc, and the discussion grew rhizomatically more than linearly, so you'll see that we sometimes refer to things said later in the roundtable. (This makes for a richer discussion, I think, but it may be a little jarring if you expect a linear conversation.)

I hope people who didn't have time or ability to join us in the "official" roundtable will feel free to offer their thoughts in the comments — as will, well, anybody else. Therefore, without further ado and all that jazz...

PARTICIPANTS

Matthew Cheney has published fiction and nonfiction in a wide variety of venues, including One Story, Locus, Weird Tales, Rain Taxi, and elsewhere. He wrote the introductions to Wesleyan University Press’s editions of Samuel R. Delany’s The Jewel-Hinged Jaw, Starboard Wine, and The American Shore (forthcoming). Currently, he is a student in the Ph.D. in Literature program at the University of New Hampshire. Craig Laurance Gidney is the author of Sea, Swallow Me & Other Stories and the YA novel Bereft. Geoffrey H. Goodwin is a journalist, author, and rogue academic with a Bachelor’s in Literary Theory (Syracuse University) and an MFA in Creative Writing (Naropa University). Geoffrey writes fiction; has taught composition and creative writing in a wide range of settings; has interviewed speculative writers and artists for Bookslut, Tor.com, Sirenia Digest, The Mumpsimus, and during Ann Vandermeer’s helming of Weird Tales; and has worked in seven different stores that have sold comic books. Keguro Macharia is a recovering academic, a lazy blogger, and an itinerant tweeter. Sometimes, he writes things on gukira.wordpress.com or tweets as @Keguro_Nick Mamatas is the author of several novels, including Love is the Law and The Last Weekend. His short fiction has appeared everywhere from Asimov’s Science Fiction to The Mammoth Book of Threesomes and Moresomes.Njihia Mbitiru is a screenwriter. He lives in Nairobi.Lavelle Porter is an adjunct professor of English at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) and a Ph.D. candidate in English at the CUNY Graduate Center. His dissertation The Over-Education of the Negro: Academic Novels, Higher Education and the Black Intellectual will be completed this spring. Finally. He’s on Twitter @alavelleporter.Ethan Robinson blogs, mostly about science fiction, at maroonedoffvesta.blogspot.com, a position he will no doubt shortly be parlaying into literary fame.Eric Schaller is a biologist, writer, and artist, living in New Hampshire and co-editor of The Revelator.THE ROUNDTABLEMatthew Cheney Locus is “The Magazine of the Science Fiction & Fantasy Field”, and so they’re primarily interested in science fiction. We don’t have to be that narrow here. But let’s start with one of the questions they start with, and see where we go: How has Delany influenced your own work or views on writing and literature? |

| detail of the cover of Dhalgren (Bantam, 1975) |

Geoffrey H. Goodwin: I got to spend a week with Chip, most minutes of every day, when he came and taught at my summer writing program when I was getting an MFA. A friend and I were the two second year science fiction devotees in the prose program (still not an easy spot in academe, though Chip has made that easier), so we knew that one of us could be his teaching assistant and decided to take it into our own hands. I remember the day Anne Waldman found out Chip was coming. I was in a poetry workship with her that day, so I raced to my friend and I swapped a fight over T.A.-ing for Chip to T.A. for Brian Evenson [who, by my reckoning, said some of the wisest comments in the other Delany roundtable] under the express agreement that my friend and I would both follow Chip around the whole time. So we did. Life-changing. Chip is still helping me learn and comprehend both literature and writing. His About Writing is one of my favorite books on the subject.

If one looks at his criticism, fiction, memoirs, and cultural relevance--not to mention everything else he’s accomplished--he’s incomparable. Sure, I remember how he offered the particle theory, where we read and read and then emit a particle on our own when we write, inspired by how we bombarded ourselves; or how he made sure to place the Marquis de Sade’s books within his young daughter’s reach because he wanted her to make her own choices about literature, and there were lessons and exercises in the workshop that were profound--but I also think of Chip as someone with whom I got to trade stories about Allen Ginsberg for stories about Philip K. Dick and Clive Barker. He’s a constellation in a tiny pantheon of living geniuses.

Nick Mamatas

I guess I appreciate Delany more as a reader than anything else. He doesn’t influence my writing, or my views. There are aspects of agreements, but I haven’t changed my mind about anything to coincide with Delany’s views. I always assign his book on writing—I’ve probably sold an extra fifty copies so far—not because I agree with everything in it, but because everything in it is worth tangling with.

Ethan Robinson

While discussions of Delany often focus on the beauty of his prose, his skillful "way with words" (usually with an example of some passage of heightened sensory description), for me this obscures one of the most remarkable aspects of his writing. It is true that he can indeed write quite beautifully when he needs to, but he is also willing to let himself write badly--that is, to take on modes of writing that are usually considered bad, clumsy, and really get to the heart of what it is that these modes are doing. I think in particular (but not exclusively) of his dialogue, which I find is very much of a piece with the generally derided style of the American science fiction magazines in its matter-of-factness, its often nakedly expository nature--even sometimes its flatness and lack of differentiation. For me it often calls to mind, say, the tendency of characters in Asimov and, later, McCaffrey (just two examples out of many possible) to talk to one another with bizarre thoroughness and "rational objectivity" about their own psychological makeups. In Delany the contrast between these passages of unattractive writing on the one hand and the heightened "poetic" passages on the other becomes a sort of structuring element, one that I think has been underappreciated and underexamined. And for myself, struggling in my own writing with the received notion that one must write "beautifully" (and/or inconspicuously; implied in both: homogeneously), seeing the value of occasional downright ugliness in Delany's writing has been very emboldening.Keguro Macharia I’ll lift Matt’s second prompt below--on beginnings--and track back to the Locus conversation, which started with “beginnings”: when did you first encounter Delany? Which is also a question about SF as a genre that (to my mind) obsesses about beginnings and endings (ecocides, genocides, monsters, hybrids, extinguishment, survival). Which is also to borrow from Lavelle about AIDS and Delany and, more broadly, the forms of extinguishment and disposability his work speaks to and, in doing so, enables us to speak about--this is the importance of Hogg as an early work. I first encountered Delany in the Patrick Merla anthology (Boys Like Us) that Lavelle mentions below. I don’t remember reading him then and, in fact, I suspect that I did not know how to read him at the time--I wanted a simple(r) narrative than he was willing to offer, a cleaner story that stayed “inside the lines,” affirmed identity, made the pleasures of identification simple, the practices of belonging uncomplicated. (Although Matt wants us to be polite, I’ll add that I read much of this impulse in the Locus discussion.)I re-encountered Delany through Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, just before I joined grad school. At the time, I was interested in formal innovation, and Times Square modeled the kind of writing and thinking I found necessary as a form of world building. I came to the novels later--Stars in My Pocket, Hogg, Mad Man, the Nevèrÿon series, at much the same time as I was reading Delany’s many essay collections. Delany helped me see form--why form matters, how form matters, to whom form matters, why formalism matters--as a project of world-building, world-remaking, inextricable from embodiment, desire, fantasy, and speculation.Njihia Mbitiru I have absolutely no idea, yet, about his influence on me. Others have spoken with great perspicacity--as well as humor (Brett Cox in the Locus roundtable being one)--about Delany’s influence. I suspect I’m still working through mine and therefore limited in what I can say about it. The first bit of Delany’s writing I encountered was The Towers of Toron, the first in the Fall of the Towers Trilogy. I was twenty-one, if I recall correctly. That was twelve years ago now. I’ve become an avid re-reader of his work, which has made me a re-reader of many other writers I onced-over. And because of this I would very much like to hazard that I am now a better reader, but this also remains to be seen: the simple fact is that proof of such is in writing, whose excellence, much as we strive toward our own finally idiosyncratic sense of it, is also a public affair.Matt: just to touch on what you’ve said about the narrative of certain of his writings--the later ones, beginning with Dhalgren (written in his late 20s and early 30s, you’ll recall! so that it’s hard to think of this as ‘late Delany’): I also resist and reject this narrative ( I’m not quite at resentment, but give me time). I find it completely non-sensical. Better and more honest to say, as a reader, that the game he’s hunting as a novelist in Dhalgren, Triton, the Neveryon series up into his present work doesn’t hold your interest. It’s a long way away from that to ‘difficult’. Only a very narrow reading of SF writing would support an assessment of Delany as ‘difficult’, if we’re talking about prose style (though I suspect that’s not what is meant, which begs the question: what do people mean exactly when they use the term ‘difficult’?). There’s so much at a SF readers’ disposal in terms of range and sophistication, or if you like, the absence of it, as there is in any other genre. I enjoy and appreciate Delany’s writing in no small part because it calls attention to precisely this.Eric Schaller Delany’s writings have influenced me more in my approach to life and thought than in writing itself. Some may dislike John Gardner’s concept and application of ‘moral fiction’ to literature, but I have always found Delany’s work moral in its suggestion of how to live a good life. In this respect, as a philosophy, I could abbreviate it as ‘compassionate individualism’: the importance of discovering and following your own path, the diversity of such paths within a population, and how to maintain your personal dignity without selfishly depriving others of theirs. The dedication in Heavenly Breakfast ("This book is dedicated to everyone who ever did anything no matter how sane or crazy whether it worked or not to give themselves a better life"), when I read it in college brought tears to my eyes, and still does.Through Delany’s writings, I like to think that I became more intentionally aware. My discovery that Delany was gay—not necessarily obvious from his earlier novels, which featured plenty of male-female couples, or from his earlier biographical information which sometimes mentioned a marriage—more specifically the worlds revealed in his non-fictional/autobiographical works such as The Motion of Light in Water, the contemporary sections from “The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals,” and, more recently, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue personified concerns that I would never experience directly. I donate to GMHC because of these works.

Matthew CheneyThere seems to be a narrative among science fiction fans, and particularly SF fans of a certain age, that there is The Good Delany of the pre-Dhalgren books, Hugo and Nebula Awards, etc. ... and then there is The Problematic Delany of Dhalgren and later. It’s a narrative of loss and disappointment, frequently accompanied by the question, “What happened?!” Because I was born in the year Dhalgren was, at least officially, published (it bears a January 1975 publication date, though it actually hit shelves a little earlier), and didn’t start reading Delany until either late 1987 or sometime in 1988, when the last Nevèrÿon book, The Bridge of Lost Desire (Return to Nevèrÿon) was published, my awareness of his career has always included what older, more traditional SF readers considered the “difficult” writings. It’s probably not surprising that I resist, reject, and resent this narrative.The book I’ve spent the most time with recently, because I’m working on a conference paper about it, is Dark Reflections, which is really beautiful and much more complexly structured than it seems at first, and which should be accessible to just about any audience, since it’s not at all pornographic and the complexity of the structure is subtle, making a basic reading relatively easy. Also, the book’s a great companion to About Writing, which it echoes often. (There’s some good discussion of the “accessibility” of Dark Reflections, particularly for heterosexual men, in Delany’s 2007 interview with Carl Freedman in Conversations with Samuel R. Delany.) But for various reasons, some having to do with events in the publishing industry, Dark Reflections does not seem to have been widely read, and is currently only in print as an e-book. It deserves a wide audience, though.So my questions for the roundtable are: What other, more useful, stories of Delany’s career could we tell? Is the Good Delany/Problematic Delany narrative useful in some way that I’m missing, some way that I can’t see because it just makes me so angry?Ethan Robinson I’ve not yet read any of his fiction after Trouble on Triton (at a certain point I decided to approach him chronologically and have been stalled at The Einstein Intersection, which my library doesn't have; I should just go ahead and buy it, probably), and haven't in fact read Dhalgren, so I can't say too much about this. But I will say that the way I see people talk about this is always very distressing to me as many of the points singled out as "problems" (too many "ideas," not enough action, unconventional storytelling, etc.) are precisely what draws me not only to Delany but to science fiction in the first place! I know the bulk of sf has always been written on a pretty, shall we say, basic level, but I confess I simply have no idea why people who want nothing but simplicity and action and conventional narrative would be attracted to this field, which seems to long for much more.

Craig Laurance Gidney

My first introduction to Delany was, interestingly enough, Dhalgren. My older brother had a copy of the book when it first came out in the ‘70s and I appropriated it. I read the book in bits and pieces during my teenaged years, and it formed my taste for esoteric and trippy SF. When people spoke about how difficult the book was, I had a hard time understanding them, maybe because I absorbed the idea of the non-linear and counter-factual texts so young. Everything of his I read is through the locus of Dhalgren. The earlier stuff is great to me because I can see the progression of themes that were refined in his later work.

Eric Schaller

I think some of the variable responses to Delany’s work may arise in part from what piece(s) were initially encountered, and how such initial experiences play into future expectations. I first encountered Delany’s work through several short stories read in high school. I remember how strongly “Time Considered as a Helix of Precious Stones” affected me, and took a perverse pleasure in the fact that my Dad didn’t follow the main character’s morphing names in the initial section. I also remember reading “Aye, and Gomorrah,” in Dangerous Visions, a story that I knew had to be important because Harlan Ellison said so. At first the story seemed slight, but it lingered and poked at my consciousness.

I don’t think I read a novel of Delany’s until the summer after graduating high school. I was working in New York City at Sloan Kettering and the novel was Dhalgren. There had been the joke published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction about the three things that mankind would never reach (“The core of the sun, the speed of light, and page 30 of Dhalgren”), but this if anything incited my interest in the novel. I was of the right age and in the right place to have the novel assume a central station in my life. But it is also one of those novels that I have returned to and re-read over the years, each time taking something new away from it. For instance, Delany having written that The Fall of the Towers was inspired by a painting of that title which did not show towers but rather reactions to their fall, I noticed a similar approach was often used in Dhalgren: the reactions of characters described before you understood to what they were reacting.

As an undergraduate at Michigan State, I sought out every Delany book I could find. And to my mind then, and still, there were differences in the approach to writing found in his early works to what I found in Dhalgren and the Return to Nevèrÿon series. The closest I can come to that difference is to say that in the earlier work Delany seemed to be thinking at a sentence to sentence level. With the later work, it seemed that he inhabited whole paragraphs at once; an individual sentence might not seem that powerful or poetic alone, but within the context of the paragraph it sang.

Geoffrey H. Goodwin

Re-reading the original Locus Roundtable, I can see how some of the context shifted based on the idea of “Samuel R. Delany, Grandmaster.” I know I think differently when “Grandmaster” gets added after anything and then we get the added aspect of, “Welcome to the Science Fiction canon,” by writers who, for no fault of their own, are far less accomplished than Chip. So we have a gay black beatnik who writes science fiction, essays, porn, comics, criticism, and just about everything else—and Chip is the kind of writer who can mean many different things to many different people. Paul Witcover’s review comparing Delany to Hendrix and Bowie really resonates with how I see Chip’s work—but Chip has kept at the work, continuing to evolve. F. Brett Cox nails it when he says Chip was producing books at different points in his life and Chip has always put himself into his books whether they were early SF, criticism, or memoir. And I’d agree that Chip isn’t cranking out spaceships or nuclear-ravaged earths the way the early works could seem—but I also swear that the ideas have been evolving since the beginning. I remember one of the earlier ones, Einstein maybe, where the chapter started with Chip quoting someone he’d talked to that week, citing it as a comment to the author. That level of intertextuality or interstitiality speaks to so much of what Chip has accomplished since then.

Nick Mamatas

As it turns out, people don’t like porn that isn’t for them. Further, most SF readers are pretty much at sea if they don’t have any tropes to think about. A straightforward and beautiful realist novel like Dark Reflections is just perplexing because it’s just about some guy living his life. No way!

I actually prefer his porn to his SF for the most part. It’s difficult to write transgressive, dirty, occasionally simply wrong stuff with such sympathy and warmth, but Delany manages it. He is an utterly unique writer in th

Strange Horizons has just posted a review by T.S. Miller of the new edition of Samuel Delany's Starboard Wine, for which I wrote an introduction. It's a generally thoughtful and well-informed review; inevitably, I have quibbles with it, but they aren't important — what's important is that, as Miller notes, the book is now available to a wider audience than ever before.

Ed Champion interviews Samuel Delany for his Bat Segundo Show. An informed, wide-ranging conversation that's very much worth the time to listen to:

Delany: And I think pornotopia is the place, as I’ve written about, where the major qualities — the major aspect of pornotopia, it’s a place where any relation, if you put enough pressure on it, can suddenly become sexual. You walk into the reception area of the office and you look at the secretary and the secretary looks at you and the next minute you’re screwing on the desk. That’s pornotopia. Which, every once in a while, actually happens. But it doesn’t happen at the density.

Correspondent: Frequency.

Delany: At the frequency that it happens in pornotopia. In pornotopia, it happens nonstop. And yet some people are able to write about that sort of thing relatively realistically. And some people aren’t. Something like Fifty Shades of Grey is not a very realistic account.

Correspondent: I’m sure you’ve read that by now.

Delany: I’ve read about five pages.

Correspondent: And it was enough for you to throw against the wall?

Delany: No. I didn’t throw it. I just thought it was hysterically funny. But because the writer doesn’t use it to make any real observations on the world that is the case, you know, it’s ho-hum.

Correspondent: How do we hook those moms who were so driven to Fifty Shades of Grey on, say, something like this?

Delany: I don’t think you’re going to.

From a rich, insightful, and fascinating review by Roger Bellin of Samuel Delany's Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders:It is certainly possible to find worthwhile the effort it takes to attempt the broadening of one's libidinal sympathies — the way a psychologically realistic novel can demand our sympathy with someone else's life and thoughts, this one demands our sympathy with his sexual desires. If science fiction, in Darko Suvin's definition, is the genre of "cognitive estrangement," then the pornographic first half of TVNS is a work of libidinal estrangement: the novel's alienating effect bears on its reader's desires, not his rational mind.

[...]

Rather than just cataloguing its protagonists' sex acts, TVNS gradually becomes a psychologically complicated novel about what they've learned from them — a reflection, through a host of little narrated daily incidents, on the ethical lessons that a life of joyous perversion has taught Eric and Shit. Sometimes it almost, implicitly, seems like a manifesto for a broad and catholic vision of queer politics; and the novel's real utopia might, finally, have less to do with the imagined community of the Dump than it does with the people themselves, and the practice of loving each other that they've discovered and worked out.

I'm still reading the book, slowly and with, frankly, awe, but everything Bellin says fits well with my reading so far.

More later, once I've reached the last page of the book...

From three of the most interesting things I've read recently and, thus, started thinking about together...

A world can be built in a sentence, but epic fantasy doesn’t want that. At the same time, it isn’t really baggy or capacious, like Pynchon or Gunter Grass. It has no V. It has no Dog Years. It has no David Foster Wallace. It isn’t a generous genre. The same few stolen cultures & bits of history, the same few biomes, the same few ideas about things. It’s a big bag but there isn’t much in it. With deftness, economy of line, good design, compression & use of modern materials, you could ram it full of stuff. You could really build a world. But for all the talk, that’s not what that kind of fantasy wants. It wants to get away from a world. This one.

Ian Sales on Leviathan Wakes by James S.A. Corey:There are some 150 million people living in the Asteroid Belt. The greatest concentration is six million in the tunnels inside the dwarf planet Ceres. There is no diversity. There is passing mention of nationalities other than the authors’ own – and a bar the characters frequent plays banghra music – but the viewpoint cast are American in outlook and presentation. Ceres itself is like some inner city no-go zone, with organised crime, drug-dealing, prostitution, under-age prostitution, endemic violence against women, subsistence-level employment… Why? It’s simply not plausible. Why would a space-based settlement resemble the worst excesses of some bad US TV crime show? The Asteroid Belt is not the Wild West, criminals and undesirables can’t simply wander in of their own accord and set up shop. Any living space must be built and maintained and carefully controlled, and everything in it must in some way contribute. A space station is much like an oil rig in the North Sea – and you don’t get brothels on oil rigs.

Further, what does all this say about gender relations in the authors’ vision of the twenty-second century? That women still are second-class citizens. One major character’s boss is a woman, and another’s executive officer is also female. But that female boss plays only a small role, and everything the XO does she does because she has the male character’s permission to do so (and it’s not even a military spaceship).

Paul Di Filippo on Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders by Samuel R. Delany:Given that the book achieves liftoff into SF territory halfway through, you need to know that Delany does not stint on his speculative conceits. His hand is as sure as of old. The future history he creates is genuinely insightful and innovative. But it’s always background, half-seen. Because our heroes are living in a semi-rural backwater and are self-professed “Luddites,” their mode of life is more archaic than the lifestyles of others. But the shifting world keeps bumping up against them, rather in the manner of Haldeman’s The Forever War. Eric and Shit move ahead almost in a series of discontinuous jumps, waking up at random moments like Haldeman’s returning soldiers to find the world growing stranger and less comprehensible and less welcoming around them. It’s as if they are riding a time machin

...having the entire intellectual armamentarium of rhetorical devices at your beck and call is far preferable to having to limit yourself to tradititional narrative tropes, when writing about truly important matters. To me, that's just simple logic.

—Samuel R. Delany

(see also,

here)

The latest issue of The Paris Review includes not only fiction by Jonathan Lethem, Roberto Bolaño, David Gates, and Amie Barrodale along with poetry by, among others, Frederick Seidel and Cathy Park Hong, but it also includes interviews with Samuel R. Delany and William Gibson.

An excerpt to whet your appetite:

DELANY

Gide says somewhere that art and crime both require leisure time to flourish. I spend a lot of time thinking, if not daydreaming. People think of me as a genre writer, and a genre writer is supposed to be prolific. Since that's how people perceive me, they have to say I'm prolific. But I don't find that either complimentary or accurate.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of yourself as a genre writer?

DELANY

I think of myself as someone who thinks largely through writing. Thus I write more than most people, and I write in many different forms. I think of myself as the kind of person who writes, rather than as one kind of writer or another. That's about the cloest I come to categorizing myself as one or another kind of artist.

And another:

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of your last three books as being science fiction?

GIBSON

No, I think of them as attempts to disprove the distinction or attempts to dissolve the boundary. They are set in a world that meets virtually every criteria of being science fiction, but it happens to be our world, and it's barely tweaked by the author to make the technology just fractionally imaginary or fantastic. It has, to my mind, the effect of science fiction.

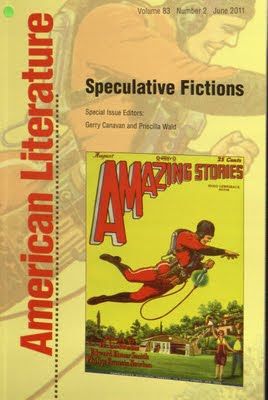

I stopped by the University library yesterday to take a look at

the latest issue of American Literature because it includes not only some interesting essays about Samuel R. Delany, a fellow I've written about a bit myself, but also a fabulous essay by

Aaron Bady, "Tarzan's White Flights: Terrorism and Fantasy Before and After the Airplane".

In this essay, there is what may be my favorite statement-required-by-a-rights-holder evah (as they say). It accompanies

a drawing by Robert Baden-Powell, author of

Scouting for Boys, that appeared in the

Daily Mail in 1938 and is titled "Policeman Aeroplanes":

Reproduced by kind permission of the Scout Association Trustees. The Scout Association does not endorse Mr. Bady's article or the use of air power against civilians.

So relieved to have that cleared up!

The cover for this issue of

American Literature, by the way, reprints the famous

August 1928 cover of Amazing Stories. If

Duke University Press, the journal's publisher, were to sell posters of this cover, I would buy one in a second, because seeing

Amazing Stories on the cover of

American Literature gives me irrational, childlike joy.

My latest Strange Horizons column has been posted, this time a celebration of Fritz Leiber's centennary.

I mentioned last week that I needed to come up with a title for my

Strange Horizons columns. Through much of last week I was fighting off the worst illness I've had in years, so perhaps the title is simply the product of fever, but nonetheless, now in a less fevered state, I like it:

Lexias. It keeps to the pattern of the other

columnists (Scores, Diffractions, Intertitles, etc.) in being a single, plural word. And it seems mostly accurate to my project, if you think of the word as Roland Barthes used it in

S/Z: "a series of brief, contiguous fragments ... units of reading" (Richard Miller's translation). (For more on Barthes, by the way,

this is an interesting site.)

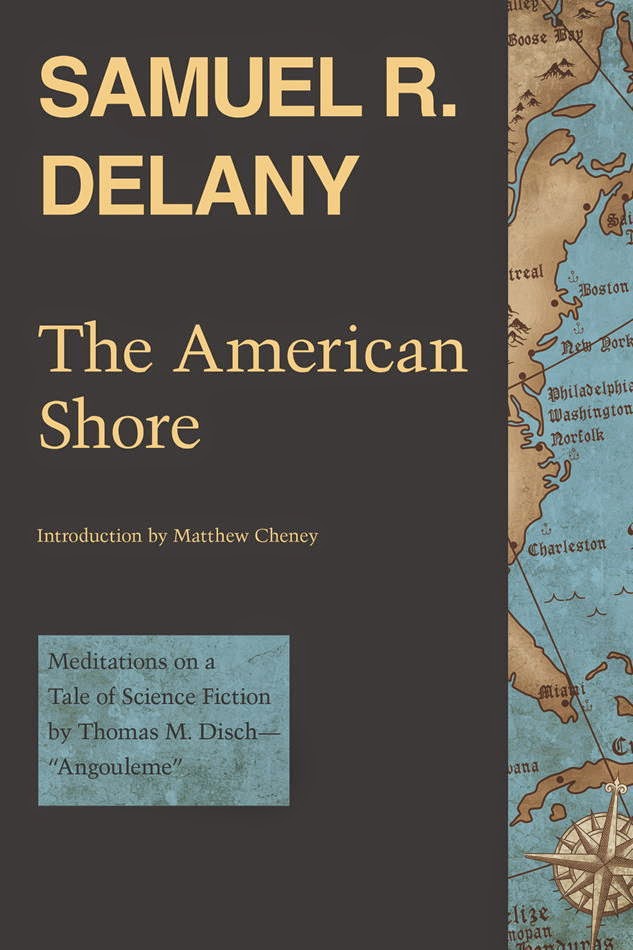

But for my purposes, "lexias" is fun, too, because it is the term Samuel R. Delany picked up (from Barthes) for

The American Shore, which can be described as a book-length study of Thomas Disch's "Angouleme" (as

S/Z can be described as a book-length study of Balzac's "Sarrasine" -- and I say "can be described as" because to say either book

is that seems to me too reductive -- each book

is an awful lot of things).

Which is not to say that I think I belong in league with Barthes or Delany (ha!), any more than anyone who picks up a term belongs in the same league with anyone who has used it before, but that I like having a title that suggests fragmentation, experimentation, close reading, and realms of both subversive (or subverted) literature and thoughtful science fiction.

Last week -- Friday, February 18, to be exact -- I trekked down to Boston for the New England premiere of Fred Barney Taylor's film

The Polymath, or, The Life & Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman. I'd

seen it a few years ago at its premiere at the TriBeCa Film Festival, and more recently on DVD, but

Fred and

Chip were both going to be at the Boston event, and I was curious to see the Q&A, since Chip hadn't been able to be at the TFF premiere, and I was interested to see what sorts of things the audience would want to discuss.

The DVD version, which is what was shown in Boston, is different from the TFF version, and, I'm told, from the version that won the Best Documentary Feature award at the Philadelphia International Gay & Lesbian Film Festival. The editing is, to my eyes, smoother; there are fewer title cards; there's some new footage; and the whole film has been through additional post-production color correction, which I found most noticeable (in a good way) during the lyrical/abstract composite shots. I hadn't particularly liked those shots in the TFF cut, finding them muddy and, frankly, kitschy -- but then when I saw the DVD version, I thought, "Oh,

that's what they were going for!" The effect is beautiful. Fred said that aside from the need for color correction, there had also been an additional problem at TFF -- the festival had insisted on everything being projected in high def, and the vast majority of

The Polymath was shot on a standard def camera (a Sony PD-150 -- the same camera, in fact, that David Lynch used to film

Inland Empire) and hadn't been converted to HD. An SD source projected as HD is ... less than ideal.

So I am happy to say that the version of

The Polymath available for sale, and shown in Boston, is a significant improvement over the first cut I saw, both in terms of content and video quality. The pieces hold together more coherently, and flow into each other more clearly. It's not a standard documentary, and that requires some adjustment for anybody who goes in expecting something like A&E's

Biography, but that's a strength, because what the film gives us, rather than a linear, then-he-did-this-then-he-did-that portrait, is a sense of Delany's many interests and knowledges, the turns of his mind. The title is brilliantly apt, both in finding some of the few labels that can, I think, adhere without too much torture to the man (polymath, gentleman), and in hinting at what the film offers (the life & opinions of).

It's a film that, I find, gains a lot from at least a second viewing -- partly because of my interest in Delany, and my knowledge of his life and works, viewing it the first time was just a way to see what's included, and it was especially difficult to assess the film then. Repeated viewings have made it clear to me that this probably isn't just a result of my own peculiarities; it's a densely-packed film, artfully constructed.

The bonus disc of the DVD offers even more -- not just the full version of Delany's own film,

The Orchid in an excellent transfer, but also over two hours of extra intervie

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 7/13/2010

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Readercon,

JPK,

Ursula Le Guin,

T.C. Boyle,

Peter Straub,

John Kessel,

anarchism,

John Barth,

grammar,

John Crowley,

genre,

punctuation,

Delany,

Junot Diaz,

Add a tag

Readercon 21 was, for me, exciting and stimulating, though this year in particular it felt like I only had a few minutes to talk with everybody I wanted to talk with. I think part of this is a result of my now living in New Hampshire rather than New Jersey, so I just don't see a lot of folks from the writing, publishing, and reading worlds much anymore.

Before I get into some thoughts on some panels and discussions, some pictures: Ellen Datlow's and Tempest Bradford's. Tempest asked everybody to make a sad face for her, not because Readercon was a sad con (just the opposite!), but because it's fun to have people make sad faces. The iconic picture from the weekend for me, though, is Ellen's photo of Liz Hand's back. I covet Liz's shirt.

And now for some only vaguely coherent thoughts on some of the panels...

I actually missed my own first panel, "Interstitial Then, Genre Now", with John Clute, Michael Dirda, Peter Dube, and Dora Goss, because the battery in my car died because of absent-mindedness on my part the night before. Luckily, I have a car battery charger, but charging took just long enough to make it so there was no physical way I could get to Burlington, MA in time for the panel. (Andrew Liptak wrote a recap for Tor.com.)

My Saturday panel, "The Secret History of The Secret History of Science Fiction", with Kathryn Cramer, Alexander Jablokov, John Kessel, Jacob Weisman, and Gary K. Wolfe went pretty well, I thought, though as so often happens, it felt like it was just getting going when it was time to end. The panel allowed John to talk about the motivations for the book, some of what he thought it accomplished, etc. -- a lot of what he said parallels what he and Jim Kelly told me when I interviewed them about the anthology. Gary Wolfe offered probably the best line of the panel: "An anthology is, inevitably, a collection of the wrong stories." (This, of course, from the critic's point of view!)

I'm not very good at inserting myself into conversations, so I did a lot of observing during the panel, piping up only to offer a sort of counter viewpoint from Gary's -- where Gary was in some ways agreeing with Paul Witcover's assertion that writers like T.C. Boyle are just using science fiction as "a trip to the playground". I was hoping we'd be able to discuss this idea a bit more, but time didn't allow it. Had it, I suppose I would have tried to say that to me the resentment of writers not routinely identified with the marketing category of "science fiction" or the community of fans, writers, and publishers that congregates under the SF umbrella -- the resentment of these writers for using the props, tropes, and moves of SF is unappealing to me for a few reasons. It's a clubhouse mentality, one that lets folks inside the clubhouse determine what the secret password is and if anybody standing outside has the right pronunciation of that password. It is, in other words, a purity test: are the intentions in your soul the right ones, the approved ones? Had we had time, I would have tried to make some sort of connection between this attitude toward non-SF writers with an attitude I've seen within the field from people toward writers of a younger generation who haven't read, for instance, e

Here's some fun news for the day: Samuel Delany is one of the five judges for the National Book Award in the Fiction category for 2010.

The entire panel is interesting: in addition to Delany, it includes Andrei Codrescu, Sabina Murray, Joanna Scott, and Carolyn See.

Oh, to be a fly on the wall for the discussions amongst such a group!

Here's a nice birthday present:

On April 1 — [Samuel R.] Delany’s 68th birthday — the Kitchen will begin staging an adaptation [of Dhalgren] called Bellona, Destroyer of Cities. Its director and writer is Jay Scheib, an MIT professor and rising theater-world star who’s been obsessed with Dhalgren for years. He once devoted an MIT course to the book, and has even adapted it into a play in German.

That news comes from

a nice overview of Delany and

Dhalgren in

New York Magazine. I thought the description of the novel as "like

Gertrude Stein: Beyond Thunderdome" was pretty amusing. (It made me want to see a picture of Gertrude Stein with Tina Turner hair.)

The play is not strictly an adaptation of the novel, it seems:

The Kitchen adaptation aims to be the next cycle of Dhalgren: It begins where the novel ends, with a new character—a woman instead of a man—entering Bellona. "In the novel," Scheib says, "when the narrator shows up, he has sex with a woman who turns into a tree. And then he has sex with a guy, and then with a girl. Then another guy. Then a guy and a girl. So we try to keep that spirit alive."

Bellona, Destroyer of Cities runs April 1-10, and there will be a post-show discussion with Chip on April 3. I would love to be there, but it's not possible. If anybody attends the show, I'd love to hear what you think of it!

The title of this post comes from a very worthwhile audio interview with Samuel R. Delany at The Dragon Page (you'll have to listen to find out what it means! The interview is about a third of the way into the podcast). It was the first time I'd publicly heard the release date of Chip's new novel, Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders, which is scheduled to be releaed in November from Alyson Books, where the great Don Weise, who was the editor for Dark Reflections, is now the publisher. A version of part of the new novel appeared in Black Clock 7 a few years ago, and Chip read some of it aloud at Readercon this past summer. It tells the story of the relationship of two men, starting in 2007 and continuing for about seventy years into the future.

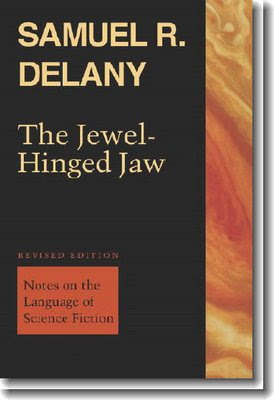

The interview also contains interesting discussions of The Jewel-Hinged Jaw, of why Chip writes what he does, of his work at Temple University, and of the growing acceptance of some forms of genre writing among the country's MFA writing programs.

Now and then, those of us who write book reviews let our guard down and make generalized statements that could be proved wrong with a single exception. Sometimes we buffer such statements with qualifiers that technically relieve them of being pure generalizations, but I doubt many readers are fooled.

For instance, last year I wrote a somewhat less than positive review of Nisi Shawl's short story collection Filter House . I even said this:

. I even said this:

While I find it easy to believe readers will experience Shawl's stories in different ways -- such is the case with any basically competent fiction -- I cannot imagine how a reader who is sensitive to literature's capabilities and possibilities could possibly say these stories offer much of a performance.

I certainly made a point of highlighting my subjectivity here: "I cannot imagine how...", but still. The intent is clear. I spent most of the review saying, in one way or another, that this book seemed to me the epitome of mediocre, and I tried to imply that it's inconceivable (

INCONCEIVABLE!) that anyone would passionately disagree with such a rational perspective.

The greater the claims, the harder they fall... Within days, I had learned that Samuel Delany thought

Filter House one of the best collections of science fiction stories published in the last decade or so. Delany and I have fairly different taste in fiction, but I deeply respect his readings of things, and even if I can't share his enthusiasm for a certain text, I've never felt like I couldn't understand what sparked and fueled that enthusiasm.

And now

Filter House has been

listed as one of the 7 best SF/Fantasy/Horror books of the year by Publisher's Weekly, and it has

won a Tiptree Award.

While I will admit I still don't understand the acclaim, I have to say I was completely and utterly wrong -- dramatically, astoundingly, INCONCEIVABLY! wrong -- in thinking that it was an impossible book to see as an example of excellence. Plenty of very smart and sensitive readers have found it to be exactly that.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 4/6/2009

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Delany,

PKD,

Add a tag

It was Samuel Delany's birthday on April 1, and the Philadelphia Inquirer has very thoughtfully given him the present of a profile, including comments from Gardner Dozois, David Hartwell, Josh Lukin, Jacob McMurray, Gregory Frost, and others.

The article even included a quote from Philip K. Dick that I don't remember encountering before. Dick reportedly called Dhalgren "a terrible book [that] should have been marketed as trash." Gave me a good chuckle, that did.

"a terrible book [that] should have been marketed as trash." Gave me a good chuckle, that did.

I should also note that I discovered the profile via a particularly excellent collection of links posted by Ron Silliman.

If anybody would like me to feel deep, visceral envy of them, they should attend the Monday, November 24 St. Marks Bookshop Reading Series where the readers are Samuel Delany and Junot Diaz.

Even if you don't care if I feel deep, visceral envy of you, you should attend if you can, because it's likely to be a phenomenal evening.

When we were working on the first volume of Best American Fantasy, I said to Jeff and Ann that I wished we could reprint some nonfiction, because some of the most wondrous things I'd encountered were essays. I had New England Review at the forefront of my mind when I said this, because I sit down and read each issue that arrives immediately, and most of what excites me is the eclectic nonfiction they publish (which is not to say the poems and stories they publish are not exciting, too; many are, and I've passed some on to Ann and Jeff. Yes, we're still working on BAF 2, the "patience is a virtue" edition...)

The latest issue of NER contains an essay by J.M. Tyree, "Lovecraft at the Automat". It's not an essay that will offer too much that's new to a Lovecraft devotee, I expect, but I'm only a casual Lovecraftian, and generally more interested in his life and circumstances than in his writing. It's fun, though, to see a journal like NER giving pages to a serious look at Lovecraft in an essay that more than once references not only Richard Wright, but also China Miéville.

The essay is mostly about Lovecraft's brief time in New York, its effect on his racism and xenophobia, the manifestations of that racism and xenophobia in his writing, and how such attitudes, transmogrified into cosmic terrors, become general enough to appeal to any of our own insecurities and neuroses. The essay begins:

In his 1945 memoir Black Boy, Richard Wright describes how as a child he became addicted to the pulp fiction supplement of a racist white newspaper. What Wright loved was reading a "thrilling horror story" in the magazine section of a Chicago paper "designed to circulate among rural, white Protestant readers." There is no reason to suspect that Wright was reading H.P. Lovecraft -- in fact, the habit was probably acquired before Lovecraft began to publish. But Wright's sense of shock and recognition when the awful truth dawns on him parallels the feelings many readers have when they discover the racism that manifests itself in Edgar Allan Poe or Lovecraft.

Later:

There is a poignancy in Wright's generosity and gratitude to such stories that implies an essential role for them in his overall intellectual growth. Could we borrow or adapt this notion from Wright for a more judicious reading of Lovecraft? It is almost as if pulp fiction, by hinting at the possibility of other worlds, whether real or fantastic, cannot help but liberate a young mind hungering for something different from the everyday reality in which it is confined. Certainly the curious desire that young writers feel to copy Lovecraft's stories does not come from a fixation on their explicit or submerged prejudices; it seems to come instead from a desire to create art suggesting hidden dimensions and extraordinary circumstances lurking invisibly in the creases, cracks, and corners of our humdrum world.

This is a familiar idea (perhaps even clichéd, which isn't to suggest wrong) about a reader's relationship to such fiction, but I think it's one worth reiterating, particularly within the context Tyree puts it in, because it highlights the reader's agency -- it recognizes that readers use texts in lots of different ways. Even stories created from a racist impulse can have an effect that is quite different from what the writer intended. Such a recognition does not excuse the original impulse, but it helps us remember that texts have all sorts of different and often contradictory contexts: the context in which they were created and the contexts in which they were, and are, received. (I wish Tyree had mentioned Nick Mamatas's

Move Under Ground, which adds yet more context to all of this in a clever and thought-provoking way.)

Tyree's essay ends abruptly, and on the whole it feels more like an interesting and potentially illuminating beginning of something longer than it feels like a satisfying essay in and of itself, but there are some marvelous passages. I was particularly taken with some of the connections Tyree makes between Lovecraft and other writers -- he brings in Conrad a few times, and compares Lovecraft's xenophobia to Henry James's similar ideas, and how the similarities manifested themselves in very different responses to New York. He also mentions Thoreau, who lived in New York in 1843:

Their writing about the city was inextricably bound up with their feeling of revulsion toward an urban scene they had no wish to understand. And in New York, both writers discovered not only what they hated, but what they loved: in Thoreau's case, Concord and the possibilities of natural wilderness, and in Lovecraft's case, colonial Providence and the survivals of the past. Interestingly, both writers started on the first literary productions of their maturity while sunk in urban unhappiness. Perhaps it was a matter of imagining anotehr world to inhabit besides the one they found themselves in.

(Tyree mentioned Thoreau's time in NY in an earlier

NER essay on William Gaddis which is well worth reading and is

available online.)

One of the interesting tidbits in the essay is that Lovecraft met the poet

Hart Crane -- the two lived in the same part of Brooklyn Heights -- and almost met

Allen Tate. This made me think that perhaps the best text to set alongside Lovecraft's New York years is Samuel Delany's "Atlantis: Model 1924" (in

Atlantis: Three Tales

), which doesn't mention Lovecraft, but Crane is essential to the story (Tate makes an appearance, too), and one passage about a young black man's excitement over pulp magazines' tales of exotic Africa ("the sound of the twentieth century infiltrating the silence of a past so deep its bottom was source and fundament of time and of mankind itself") ends:

...the magazines were in a shopping bag leaning up by the brick wall when he lifted it on the paper beneath was a picture of KKK men in bedsheets holding high a torch menacing the darkness of the black newsprint from within the photo's right framing the shopping bag just sitting there Sam thought where anyone could have taken it

Anyone at all.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 2/10/2008

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reginald Shepherd,

Delany,

queer,

poetry,

essays,

Writing,

Quotes,

Delany,

queer,

Reginald Shepherd,

Add a tag

One of the best new essay collections I have read in a long time is Reginald Shepherd's Orpheus in the Bronx: Essays on Identity, Politics, and the Freedom of Poetry . I first encountered Shepherd some years back in an issue of Poets & Writers with an essay he wrote on Samuel Delany, though I didn't realize he had written it until I discovered it reprinted in Orpheus in the Bronx. I first noted Shepherd's name when I discovered his blog, which is consistently rich with thoughtful posts on poetry, writing, teaching, and living. (Shepherd has done some additional blogging the Poetry Foundation's Harriet blog, which has become a diverse and fascinating site of discussion about all sorts of different views of poetry. Some of Shepherd's recent posts have stirred up passionate, valuable discussion in their comments threads and elsewhere.)

. I first encountered Shepherd some years back in an issue of Poets & Writers with an essay he wrote on Samuel Delany, though I didn't realize he had written it until I discovered it reprinted in Orpheus in the Bronx. I first noted Shepherd's name when I discovered his blog, which is consistently rich with thoughtful posts on poetry, writing, teaching, and living. (Shepherd has done some additional blogging the Poetry Foundation's Harriet blog, which has become a diverse and fascinating site of discussion about all sorts of different views of poetry. Some of Shepherd's recent posts have stirred up passionate, valuable discussion in their comments threads and elsewhere.)

I've just written and submitted a review of Orpheus in the Bronx, and will offer more details on that once I know its fate. I think this is a book with broad appeal, a book that should be read by writers and readers of all sorts, not just those who are particularly interested in poetry and its various factions and fascinations. To persuade you toward this idea, here's a tiny and more-or-less random selection from some of the many interesting passages in the book...

From the introduction:

History, politics, economics, authorial biography, all contribute to the matter of poetry and even condition its modes of being, but they don't determine its shape, its meaning, or its value. Similarly, it's not that a poet's social position and background don't matter and shouldn't be discussed -- they obviously condition (but do not wholly determine) who he or she is and what she or he writes -- but that they don't define the work or its aesthetic value. They should not be used to put the writer into a box or to expect him or her to write in a certain way or on certain topics, to obligate him or her to "represent" or speak for his or her social identity (as if anyone had only one, or even two or three).

From "The Other's Other: Against Identity Poetry, For Possibility":

I have never looked to literature merely to mirror myself back to me, to confirm my identity to myself or to others. I already have a self, even if one often at odds with itself, and if anything I have felt burdened, even trapped, by that self and its demands, by the demands made upon it by the world. Many minority writers have spoken of feeling invisible: I have always felt entirely too visible, the object of scrutiny, labeling, and categorization. Literature offered a way out of being a social problem or statistic, a way not to be what everyone had decided I was, not to be subject to what that meant about me and for me. But even if one has a more sanguine relation to selfhood, Picasso's admonition should always be kept in mind: art is called art because it is not life. Otherwise, why would art exist? Life already is, and hardly needs confirmation.

From "Shadows and Light Moving on Water: On Samuel R. Delany":

There is a convergence between the position of poetry and the position of science fiction in contemporary American culture. Both are highly marginal discourses. Poetry has a great deal of residual cultural cachet (as attested by its use as an all-purpose honorific: a good quarterback is "poetry in motion"), but few people read it (there are many times more would-be poets than readers of poetry); science fiction lacks prestige but is widely read (often somewhat abashedly, as if one shouldn't admit to such an adolescent habit).

At their best, science fiction and poetry have in common the production and presentation of alternative worlds in which the rules, restrictions, and categories of our world don't apply; it was this freedom from the tyranny of what is, the domination of the actually existing, that attracted me to both, first science fiction and then poetry.

From "Why I Write":

To attempt something new and fail is much more interesting than to attempt something that's already been done and fail. I don't want to write something just because I know I can, just to reaffirm what I already know. Of course, to say that I don't want to do the same thing twice is to assume that I've done something in the first place. I not only don't know what I can do, I don't know what I've done. How could one, not having access to the vantage point of posterity? With every poem I'm trying to do something that I can't achieve, to get somewhere I'll never get. If I were able to do it, if I were able to get there, I'd have no reason to continue writing.

By: Rebecca,

on 5/25/2007

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

A-Featured,

World History,

gulag,

emel’ianovich,

boots’—lapti,

died—aleksei,

barracks—papa,

exiled,

“truths”,

voices,

Add a tag

Today we are proud (and a bit sad because it’s over) to present part 5 of Lynne Viola’s piece on her archival research for her book The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin’s Special Settlements. Check out her previous posts here.

It would have been impossible to write this book without access to the archives. The archives, however, tell only a part of the story. (more…)

Share This

I have not yet read Starboard Wine (though I've been intensively reading and rereading The Jewel-Hinged Jaw and Longer Views for the past year or two). Have just ordered this edition.

Read your linked introduction--was glad to see you trying to disabuse readers of the notion that there exists any kind of hierarchy of quality/importance between sf and non-sf, regardless of which is seen to be "on top." I do not participate (or at least have not participated) in fandom and have only the slightest acquaintance with sf criticism after about 1985 (a problem I'm somehow having trouble remedying), but the sf vs. lit battles are incredibly tiresome, and fruitless, no matter who engages in them.

Excited to see there is a more extended discussion of Joanna Russ than I have yet seen by him...

Excited too to see that there is further discussion of his notion of sf's "origins," because what I've seen him write on that subject is very refreshing, but brings up many questions in my mind...certainly his version seems much more valuable to me than, say, Brian Aldiss's notion that sf is "really" a continuation of the gothic and utopian traditions, with genre sf as just a poor example of the form; but then I think eliminating Mary Shelley and Jules Verne and so on as formative also forfeits a lot of explanatory power; having a more extensive treatment of Delany's views on the matter will hopefully give me more to grab on to while figuring all this out for myself.

Shorter: thanks for making me aware of the new edition!

Nice to see your work appreciated.