new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: slavery, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 80

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: slavery in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Sue Morris,

on 6/23/2014

Blog:

Kid Lit Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Children's Books,

Picture Book,

freedom,

NonFiction,

Historical Fiction,

Favorites,

slavery,

children's book reviews,

Gretchen Woelfle,

Carolrhoda Books,

Declaration of Independence,

Lerner Publishing Group,

1776,

Alix Delinois,

American Revolutionary War,

Library Donated Books,

6 Stars TOP BOOK,

Top 10 of 2014,

Massachusetts Constitution of 1780,

Add a tag

.

.

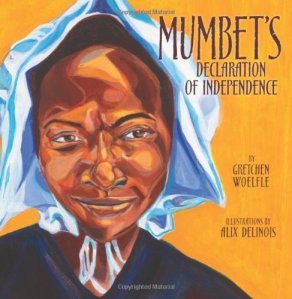

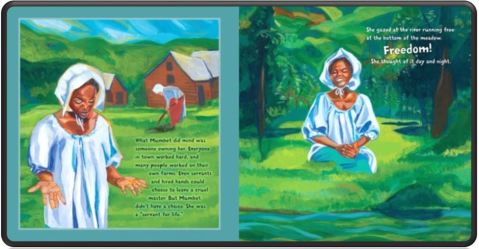

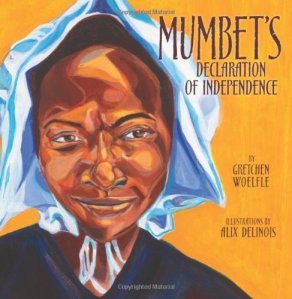

Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence

by Gretchen Woelfle & Alix Delinois, illustrator

Carolrhoda Books 2/01/2014

978-0-7613-6589-1

Age 7 to 9 32 pages

.

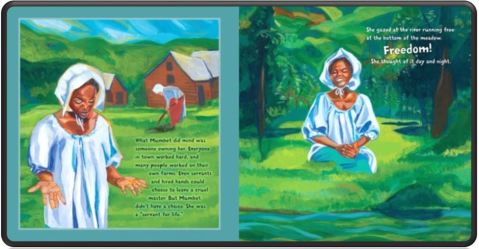

“All men are born free and equal.” Everybody knows about the Founding Fathers and the Declaration of Independence in 1776. But the founders weren’t the only ones who believed that everyone had a right to freedom. Mumbet, a Massachusetts slave believed it too. She longed o be free, but how? Would anyone help her in her fight for freedom? Could she win against her owner, the richest man in town? Mumbet was determined to try. Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence tells her story for the first time in a picture book biography, and her brave actions set a milestone on the road toward ending slavery in the United States.”

Opening

“Mumbet didn’t have a last name because she was a slave. She didn’t even have an official first name. Folks called her Bett or Betty. Children called her Mom Bett or Mumbet. Others weren’t so kind.”

The Story

The year is 1776 and the United States begins its fight for freedom from the rule of the British by declaring on paper their Declaration of Independence. Mumbet is a slave owned by the richest man in town—the one who is usually the most powerful in town. Colonel John Ashley lived in Massachusetts and owed many businesses. He might have been kind, but his wife was definitely a cruel woman when it came to her husband’s slaves. Mumbet worked for Mrs. Ashley, usually in her kitchen. Mumbet hated that another human owned her, as wouldn’t you or I. She knew servants and hired hands could leave a cruel employer, but Mumbet had no recourse—she’s is property.

As the founding fathers gathered to write the Declaration of Independence, which started the seven-year war against the British, Mumbet served refreshments and tried to listen. The men were against British taxes and feared losing all their rights under British rule. As Mumbet listened, she heard one man say,

“He [the King of England] would make us slaves.”

And,

“Mankind in a state of Nature are equal, free, and independent . . .

God and Nature have made us free.”

After seven years of war against England, and freedom won, the town held a meeting to introduce The Massachusetts Constitution in 1780. It declared,

“All men are born free and equal.”

Mumbet wondered if that meant her. She approached Theodore Sedgwick, a young lawyer who helped draft the Declaration of Independence, and asked him to represent her in a fight for her personal freedom under the new Massachusetts law. He accepted. Mr. Sedgwick reminded the judge and jury that no law existed in Massachusetts making slaves legal and the new constitution now made them illegal. Would the judge and jury agree with Mr. Sedgwick and grant Mumbet her freedom—and the freedom of all slaves in Massachusetts in the process?

Review

Mumbet’s story, a true story, is an unusual biography in that I don’t recall hearing about this woman in any history class, not even American History. Mumbet had strength unseen except on rare occasions. To take your master to court to demand your freedom was a crazy idea. Even white women were still considered their husband’s chattel, why would a slave be above that. How was Mumbet going to convince a jury—not of her peers—and a judge—most likely friends with the richest man in town—that she deserved her freedoms for the same reason as the men deserved theirs from Britain? The new Massachusetts Constitution was not that old and here is this slave trying to gain her freedom, yet she is property. This must have caused some laughter, smirking, and hate. I find this story truly moving. Her new name became Elizabeth Freeman, a most deserved last name.

Mumbet’s clear and succinctly written story tells of an amazing, intelligent, and courageous woman who dared stand up for her rights when no one ever considered her to have rights. She entered a paternal courtroom, a jury not of her peers, and a town overflowing with curious citizens not all of which could have been happy Mumbet wanted freedom. It was probably more hostile, considering ever man probably stood to lose his slaves if Mumbet were successful. That makes Mumbet one of the strongest woman to have ever lived in the United States.

The illustrations are profoundly beautiful with deep rich colors. Even the end pages have an elegance to them. Alix Delinois represented that time in America accurately, with facial expressions that must have matched the frustration felt by most citizens, as the founding fathers wrote the Declaration of Independence. Mrs. Ashley’s cruelty is shockingly visible, immediately making you feel empathy for Mumbet and her daughter. For people sincerely wanting freedom and respect from the British, some were capable of much harm to others.

Thankfully, someone thought to write down Mumbet’s story giving the author great accounts of Mumbet’s life and challenges before, during, and after that day in court. After the story are two pages of author notes. They tell of the help the author received from Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Theodore Sedgwick’s daughter. Catharine wrote Mumbet’s story as it happened, leaving accurate historical documents from which this story was written. These notes are fascinating.Teachers would do well to keep Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence as an adjunct history lesson. It is a story not told in most history classes. Gretchen Woelfle’s impeccable research and storytelling skills gives us a story of slavery not well known in the very country in which it happened—until now. Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence should fascinate kids and adults alike.

MUMBET’S DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE. Text copyright © 2014 by Gretchen Woelfle. Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Alix Delinois. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Carolrhoda Books, Minneapolis, MN.

Buy a copy of Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence at Amazon —B&N—iTunes—Book Depository—Carolrhoda Books—at your local bookstore.

—B&N—iTunes—Book Depository—Carolrhoda Books—at your local bookstore.

.

Learn more about Mumbet’s Declaration of Independence HERE.

Meet the author, Gretchen Woelfle, at her website: http://www.gretchenwoelfle.com/

Meet the illustrator, Alix Delinois, at his website: http://alixdelinois.com/home.html

Find more books a the Carolrhoda Books blog: http://carolrhoda.blogspot.com/

Carolrhoda Books is a division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc. https://www.lernerbooks.com/

.

Also by Gretchen Woelfle

Write On, Mercy!: The Secret Life of Mercy Otis Warren

All the World’s a Stage: A Novel in Five Acts

The Wind at Work: An Activity Guide to Windmills

Also by Alix Delinois

Eight Days: A Story of Haiti

Muhammad Ali: The People’s Champion

.

.

Filed under:

6 Stars TOP BOOK,

Children's Books,

Favorites,

Historical Fiction,

Library Donated Books,

NonFiction,

Picture Book,

Top 10 of 2014 Tagged:

1776,

Alix Delinois,

American Revolutionary War,

Carolrhoda Books,

children's book reviews,

Declaration of Independence,

freedom,

Gretchen Woelfle,

Lerner Publishing Group,

Massachusetts Constitution of 1780,

slavery

By: Alice,

on 4/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Law,

Politics,

Current Affairs,

slavery,

America,

African Americans,

*Featured,

criminal justice,

criminal convictions,

Felon disfranchisement,

History of American Citizenship,

Living in Infamy,

Pippa Holloway,

voting rights,

felon,

disfranchisement,

disfranchise,

Add a tag

By Pippa Holloway

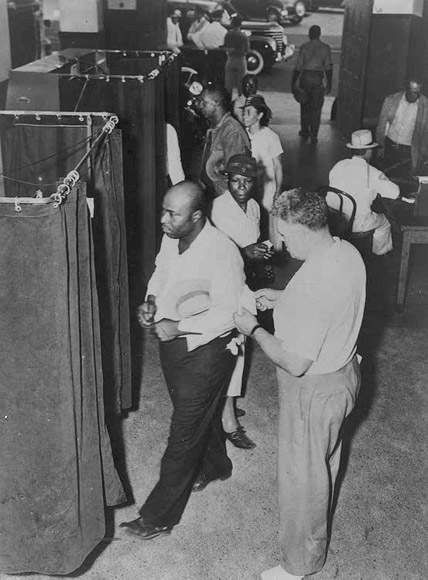

Nearly six million Americans are prohibited from voting in the United States today due to felony convictions. Six states stand out: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. These six states disfranchise seven percent of the total adult population – compared to two and a half percent nationwide. African Americans are particularly affected in these states. In Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia more than one in five African Americans is disfranchised. The other three are not far behind. Not only do individuals lose voting rights when they are incarcerated, on probation, or paroled, a common practice in many states, but some or all ex-felons are barred from voting. All six of these states have non-automatic restoration processes that make it difficult or impossible to have one’s rights restored. Not coincidentally, all of these states maintained a system of racial slavery until the Civil War.

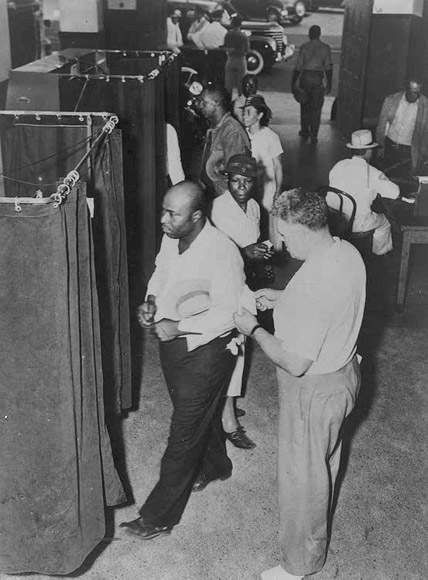

Voters at the Voting Booths. ca. 1945. NAACP Collection, The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship, Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the other end of the spectrum are northeastern states, mostly those in New England, which put up few obstacles to voting by convicted individuals. Maine and Vermont are the only states in the nation that do not disfranchise anyone for a crime, even individuals who are incarcerated. Among the remaining 48 states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire disfranchise the smallest percentage of convicted individuals. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania are also far below the national average.

Generalizations about regional difference are complex should be made cautiously. Although the six states with the highest rates of disfranchisement are all in the South, six other states also impose life-long disfranchisement for some or all felons. Arizona and Nevada have relatively high rates of felon disfranchisement. Midwestern states, particularly Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan, have low rates of felon disfranchisement, as does North Dakota. Nonetheless, the Northeast and South stand in stark contrast.

Regional differences in felon disfranchisement today are the result of regionally divergent histories of slavery and criminal justice. New England states had outlawed slavery by 1800. Soon, they also stopped treating convicts like slaves, barring state-administered corporal punishment for criminal offenses in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Instead, northeastern states embraced an ideology of criminality that emphasized rehabilitation. This attitude toward both slavery and punishment led many citizens and lawmakers in the northeast to oppose disfranchisement of convicts or at least curb the reach of this punishment. In the colonial era, Connecticut limited the courts that could deny convicts the vote. Maine’s 1819 constitutional convention rejected a proposal to disfranchise for crime. Vermont ended the practice in 1832. In other northeastern states proponents of such disfranchisement measures faced strong opposition. For example, Pennsylvania’s 1873 constitutional convention restricted felon disfranchisement to those convicted of election-related crimes; an effort to disfranchise convicts in Maryland in 1864 passed only after a long debate.

In contrast in the nineteenth-century South two groups were permanently cast out of full citizenship: African Americans and convicts. Although the enslavement of African Americans ended in 1865, “infamy” – the legal status of those convicted of serious crimes – was imposed on a growing number of the new black citizens. Accusations of prior crimes were used in the 1866 election as one of the first tools used to deny the vote to former slaves. In the 1870s, nearly every state in the former Confederacy (Texas being the exception) modified its laws to disfranchise for petty theft, a move celebrated by white leaders as a step toward disfranchising African Americans.

The legacy of slavery and segregation in the South is important to this story but so is the different regional trajectory of criminal justice. All southern states except South Carolina and Georgia (states today that still have among the lowest rates of disfranchisement in the South) enacted laws disfranchising for crime between 1812 and 1838, and there is little evidence of dissent or debate over this punishment anywhere in the region. Furthermore, southern states rejected the concept of criminal rehabilitation and focused instead on punishment. After the Civil War “convict lease” systems replicated in many ways the system of slavery for those who fell into it, creating a class of mostly-black individuals who were subject to physical punishment, public abuse, and humiliation, and denied voting rights.

In the past, as is also true today, individuals with criminal convictions fought long battles to regain their voting rights. Far from being a population that is uninterested in politics, individuals barred from voting have challenged obstacles to re-enfranchisement and overcome tremendous hurdles to have their voting rights restored. Consider the case of Jefferson Ratliff, an African American farmer living in Anson County, North Carolina, who in 1887 paid the court an astounding $14 to have his citizenship rights restored, ten years after his conviction for larceny (including three years’ incarceration) for stealing a hog. In Giles County, Tennessee in 1888 a man named Henry Murray paid $2.70 in court costs in an unsuccessful effort to have his voting rights restored. In other cases, poor and illiterate individual petitioners facing a complicated legal process sought help from friends and neighbors. In Georgia, Lewis Price petitioned Governor William Y. Atkinson in 1895 for a pardon so that he could vote. He explained, “I am a poor ignorant negro and I have no money to pay to the lawyers to work for me. So I have to depend on my friends to do all of my writing.”

The historical record shows that state and local governments have consistently failed, throughout the nation’s history, to enforce these laws in a fair and uniform way. Coordinating voter registration lists with criminal court records and pardon records — difficult in today’s world of information technology — was nearly impossible in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. People who should have been able to vote were often denied the vote due to false allegations of disfranchising offenses; convictions were secured through suspect judicial processes prior to an election for partisan ends; and people who should have been disfranchised often voted. Sometimes these appear to have been honest mistakes made by officials charged with merging complicated statutory and constitutional requirements with voter registration data and court records. In many cases though, other agendas—partisan, racial, personal—seem to have been at work. In short, felon disfranchisement laws have long been subject to error and abuse.

Race both rationalized and motivated laws imposing lifelong disfranchisement for certain criminal acts in the post-Civil War period. Since then a variety of factors have led to the persistent sense, particularly in southern states, that individuals with prior criminal convictions are marked with a disgrace and contamination that is incompatible with full citizenship. Felon disfranchisement today preserves slavery’s racial legacy by producing a class of individuals who are excluded from suffrage, disproportionately impoverished, members of racial and ethnic minorities, and often subject to labor for below-market wages. In these six southern states, the ballot box is just as out of reach for former convicts as it was for enslaved African Americans two centuries ago.

Dr. Pippa Holloway is the author of Living in Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, published Oxford University Press in December 2012. She is Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University. Contemporary data comes from Christopher Uggen, Sara Shannon, Jeff Manza, “State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2010.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

jilleisenberg14,

on 4/19/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

poetry,

slavery,

Educators,

National Poetry Month,

reading comprehension,

close reading,

African/African American Interest,

common core standards,

CCSS,

Curriculum Corner,

appendix b,

ELA common core standards,

Add a tag

Jill Eisenberg, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching English as a Foreign Language to second through sixth graders in Yilan, Taiwan as a Fulbright Fellow. She went on to become a literacy teacher for third grade in San Jose, CA as a Teach for America corps member. She is certified in Project Glad instruction to promote English language acquisition and academic achievement. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

Jill Eisenberg, our Resident Literacy Expert, began her career teaching English as a Foreign Language to second through sixth graders in Yilan, Taiwan as a Fulbright Fellow. She went on to become a literacy teacher for third grade in San Jose, CA as a Teach for America corps member. She is certified in Project Glad instruction to promote English language acquisition and academic achievement. In her column she offers teaching and literacy tips for educators.

1. Teaching Students About Narrator Bias

Etched In Clay is a compelling case study for narrator bias and trustworthiness. The text structure with 13 narrators and its economy of words make Dave’s story captivating, especially to middle grade  students who are beginning to engage with primary sources from the period of American slavery. Students can analyze how each speaker’s social experiences, status, motivations, and values influence his/her point of view, such as evaluating the poems of the slave-owners who would have had a vested interest in popularizing a particular narrative of slavery.

students who are beginning to engage with primary sources from the period of American slavery. Students can analyze how each speaker’s social experiences, status, motivations, and values influence his/her point of view, such as evaluating the poems of the slave-owners who would have had a vested interest in popularizing a particular narrative of slavery.

Using multiple perspectives to tell the story of one life is a striking display of how events can be interpreted and portrayed by different positions in the community. Students face the task of examining the meaning and nuance of each narrator (13 in total!) and what they choose to convey (or don’t).

Discussion questions include:

- Why might the author choose to share Dave’s story using multiple speakers? How do multiple narrations develop or affirm the central idea?

- How do the author’s choices of telling a historical story in present tense and first person narration affect our sympathy toward the narrators and events in the book?

- Select a poem, such as “Nat Turner,” and defend why the author chose a particular narrator to tell that event or moment. How would the event and poem be different if another, like Reuben Drake, had told it?

- Are there narrators the readers can trust more than others? Why or why not? What makes a narrator (un)trustworthy? How is each narrator (un)reliable? Why might one of these narrators not tell readers the “whole” truth? Does having more than one narrator make the story overall more reliable? Why or why not?

- How does a narrator’s position in society or in Dave’s life affect what he/she knows? How does the historical context affect what a narrator may or may not know and his/her reliability? How can readers check a narrator’s knowledge of facts?

- What is the motivation of each narrator to share?

- Does this alternation between narrators build compassion or detachment for Dave in readers? How so?

- Why is it important to learn the history of slavery from slaves themselves?

- Compare and contrast the conditions of slavery from Dave’s point of view and Lewis Miles.

- How do the slaveholders depict the relationships with their slaves? How do the slaves depict their relationships with the slaveholders?

- Compare Dave and Lewis Miles’ perceptions of the Civil War.

- Consider whether Dave and David Drake should be considered one perspective or two.

- Contrast how each narrator feels about antebellum South Carolina.

- Who might be the audience the narrators are telling their version of events to (themselves, God, a news reporter, etc.)? Are they the same? Why is intended audience important to consider?

- Argue whether 13 points of view flesh out this figure or make Dave and his life even more elusive.

2. Poetry Month and Primary Sources

As “Primary Sources + Found Poetry = Celebrate Poetry Month” suggests, the Library of Congress proposes an innovative way to combine poetry and nonfiction. Teaching With The Library of Congress recently re-posted the Found Poetry Primary Source Set that “supports students in honing their reading and historical comprehension skills by creating poetry based upon informational text and images.” Students will study primary source documents, pull words and phrases that show the central idea, and then use those pieces to create their own poems.

This project not only enables teachers to identify whether a student grasps a central idea of a text, but also encourages students to interact with primary sources in much the same way as Etched In Clay’s Andrea Cheng. When researching Dave’s life and drawing inspiration for her verses, Andrea Cheng integrated the small pieces of evidence of Dave’s life, including poems on his pots and the bills of sale.

3. Common Core and the Appendix B Document

Many middle school educators are currently using Henrietta Buckmaster’s “Underground Railroad,” a recommended text exemplar for grades 4-5, and Ann Petry’s Harriet Tubman: Conductor on the Underground Railroad and Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass An American Slave, Written by Himself, recommended text exemplars for grades 6-8 in the Common Core State Standards’ Appendix B document.

Educators can couple Etched In Clay with those texts to involve reluctant or struggling readers, prepare incoming middle school students, and scaffold content and language for English Language Learners. Additionally, Andrea Cheng’s biography offers educators an inquiry-based project for ready and advanced readers to analyze “how two texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take” (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.9).

For a more inclusive, diversity-themed collection of contemporary authors and characters of color, check out our Appendix B Diversity Supplement.

Further reading:

Andrea Cheng on Writing Biography in Verse

A Poem from Etched in Clay

Filed under:

Curriculum Corner Tagged:

African/African American Interest,

appendix b,

CCSS,

close reading,

common core standards,

Educators,

ELA common core standards,

History,

National Poetry Month,

poetry,

reading comprehension,

slavery

By:

keilinh,

on 4/11/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Holidays,

poetry,

poetry Friday,

slavery,

poems,

guest blogger,

pottery,

National Poetry Month,

Andrea Cheng,

Musings & Ponderings,

dave the potter,

david drake,

Etched in Clay,

Add a tag

Andrea Cheng is the author of several critically-acclaimed books for young readers. Her most

Andrea Cheng is the author of several critically-acclaimed books for young readers. Her most  recent novel, Etched in Clay, tells the story in verse of Dave the Potter, an enslaved man, poet, and master craftsperson whose jars (many of which are inscribed with his poetry and writings) are among the most sought-after pieces of Edgefield pottery. Etched in Clay recently won the Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award.

recent novel, Etched in Clay, tells the story in verse of Dave the Potter, an enslaved man, poet, and master craftsperson whose jars (many of which are inscribed with his poetry and writings) are among the most sought-after pieces of Edgefield pottery. Etched in Clay recently won the Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award.

April is National Poetry Month, so we asked author Andrea Cheng to share one of her favorite poems from Etched in Clay:

FEATURED POEM

Etched in Clay, p. 65

A Poem!

Dave, July 12, 1834

The summer’s so hot,

it’s like we’re living

in the furnace.

The clay doesn’t like it either,

getting hard on me

too quick.

I better hurry now,

before the sun’s too low to see.

What words will I scrawl

across the shoulder

of this jar?

I hear Lydia’s voice in my head.

Be careful, Dave.

Those words in clay

can get you killed.

But I will die of silence

if I keep my words inside me

any longer.

Doctor Landrum used to say

it’s best to write a poem a day,

for it calms the body

and the soul

to shape those words.

This jar is a beauty,

big and wide,

fourteen gallons

I know it will hold.

I have the words now,

and my stick is sharp.

I write:

put every bit all between

surely this jar will hold 14.

Andrea Cheng: There are three poems in Etched in Clay which speak directly about the act of writing. In the first one, “Tell the World,” (EIC p. 38) Dave writes in clay for the first time. Using a sharp stick, he carves the date, April 18, into a brick; he is announcing to the world that on this day, “a man started practicing/his letters.” In the poem called “Words and Verses,” (EIC p. 52) Dave thinks about writing down one of the poems that has been swirling around in his head as he works on the potter’s wheel. Finally, in “A Poem!” (EIC p. 67) Dave actually carves a couplet into one of his jars. His words are practical and ordinary; he simply comments on the size of the jar. But he is no longer silent.

Further Reading:

Andrea Cheng on Writing Biography in Verse

An interview with Andrea Cheng about Etched in Clay in School Library Journal

A look at how Andrea Cheng made the woodcut illustrations for Etched in Clay

Filed under:

guest blogger,

Holidays,

Musings & Ponderings Tagged:

Andrea Cheng,

dave the potter,

david drake,

Etched in Clay,

National Poetry Month,

poems,

poetry,

poetry Friday,

pottery,

slavery

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 3/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

human trafficking,

International Criminal Court,

British navy,

trafficking,

crime against humanity,

slave trade,

slave,

*Featured,

enslavement,

international law,

International Human Rights Law,

abolition of slavery,

forced labor trafficking,

jenny s. martinez,

transatlantic slave trade,

martinez,

transatlantic,

Books,

History,

Law,

Current Affairs,

slavery,

World,

jenny,

human rights,

ships,

Add a tag

By Jenny S. Martinez

Today, 25 March, is International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. But unfortunately, the victims of slavery were not all in the distant past. Contemporary forms of slavery and forced labor remain serious problems and some reputable human rights organizations estimate that there are some 21-30 million people living in slavery today. The issue is not limited to just a few countries, but involves complex transnational networks that facilitate human trafficking. Just as in the past, international cooperation is necessary to end this international problem.

International law played a key role in ending the transatlantic slave trade in the 19th century. In the year 1800, slavery and the slave trade were cornerstones of the Atlantic world and had been for centuries. Tens of thousands of people from Africa were carried across the Atlantic each year, and millions lived in slavery in the new world. In 1807, legislatures in both the United States and Britain — two countries whose ships had been key participants in the trade — banned slave trading by their citizens. But two countries alone could not stop what was a truly international traffic, which quickly shifted to the ships of other nations. International cooperation was required.

Beginning in 1817, Britain negotiated a series of bilateral treaties banning the slave trade and creating international courts to enforce that ban. These were, I suggest, the first permanent international courts and the first international courts created with the aim of enforcing a legal rule designed to protect individual human rights. The courts had jurisdiction to condemn and auction off ships involved in the slave trade, while freeing their passengers. The crews of navy ships that captured the illegal slave vessels were entitled to a share of the proceeds of the sale of the vessels, creating an incentive for vigorous policing. By 1840, more than twenty nations — including all the major maritime powers involved in the transatlantic trade — had signed treaties of various sorts (not all involving the international courts) committing to the abolition of slave trading. By the mid-1860s, the slave trade from Africa to the Americas had basically ceased, and by 1900, slavery itself had been outlawed in every country in the Western Hemisphere.

While treaties today prohibit slavery and the slave trade, international efforts at eradicating modern forms of slavery and forced labor trafficking are inadequate. Looking to the lessons of the past, international policy makers should consider implementing a more robust system for dismantling modern day slavery. A system of property condemnation with economic incentives for whistleblowers could again be used to leverage enforcement power; someone who turns in a human trafficker could be entitled to a share of the proceeds of a sale of the trafficker’s assets. Similarly, international courts could be used in especially severe cases. Enslavement is a crime against humanity under the statute of International Criminal Court, and severe cases involving transnational trafficking networks with large numbers of victims might meet the criteria for ICC jurisdiction. Violent acts in wartime are more visible international crimes, but the human impact of enslavement is no less severe or deserving of international justice.

It is not enough to remember past victims of enslavement; to truly honor their memory, we must do something to help those who are enslaved today.

Jenny S. Martinez is Professor of Law and Justin M. Roach, Jr., Faculty Scholar at Stanford Law School. A leading expert on international courts and tribunals, international human rights, and the laws of war, she is also an experienced litigator who argued the 2004 case Rumsfeld v. Padilla before the U.S. Supreme Court. Martinez was named to the National Law Journal’s list of “Top 40 Lawyers Under 40.” She is the author of The Slave Trade and The Origins of International Human Rights Law (OUP 2012), now available in paperback.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Victims of slavery, past and present appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 2/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

caribbean,

africans,

Humanities,

*Featured,

plantations,

plantation,

African American Religion,

Caribbean Slavery,

noel erskine,

plantation church,

erskine,

Books,

History,

Africa,

Religion,

black history month,

slavery,

America,

african american,

Add a tag

In honor of Black History Month, we sat down with Noel Erskine to learn more about the Plantation Church—the religions that formed on plantations during slavery—and its roots in the Caribbean.

How was the Plantation Church formed?

The Plantation Church was formed through the traffic across the Black Atlantic of Africa’s children, packed like sardines, and treated as human cargo, to work on plantations in the Americas. The plantation was at first a site of human bondage, and provided the context for chattel slavery, where the entire family was brutalized as they realized that there was a connection between higher sugar prices and cruel treatment of slaves. In plantation society the political power of the African chief was transferred to the white master, except in the context of the plantation, there were no safeguards for women and children. The entire family was dehumanized. Plantation etiquette required submission to the wishes of the master and failure to comply would often elicit a violent response. The will of the master applied to every aspect of plantation life. The master had the right to whip, sell, or trade members of the family whenever or for whatever reason. Africans found it difficult at first to mount a credible form of resistance against the violence perpetrated against them on plantations.

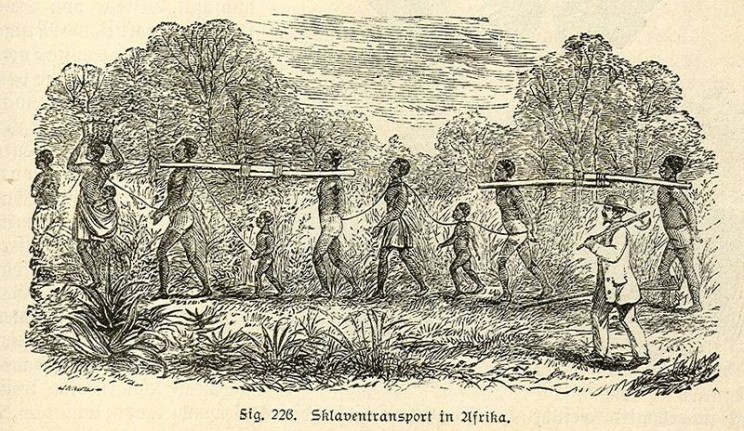

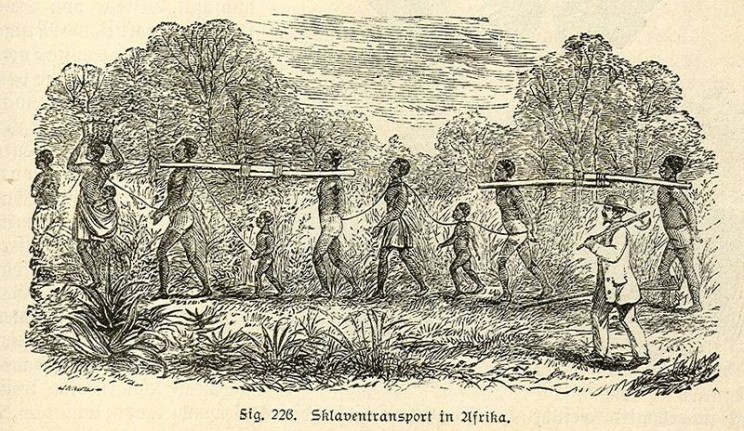

Slaves being transported in Africa, 19th century engraving. From Lehrbuch der Weltgeschichte oder Die Geschichte der Menschheit by William Rednbacher, 1890. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Why was the Plantation Church formed?

It is often forgotten that Africans who were captured and brought against their will to work on plantations in the New World left institutions of their clan and tribe behind. The creation of the Plantation Church was an attempt to hold body and soul together in an alien environment. In the Plantation Church, which was at first an African Church, Africans “stolen from the homeland” had to compensate for the loss of language, culture, and the constant change of environment as they were often sold and separated from members of their families. The cruelty meted out to Africans who traversed the Black Atlantic on route to the Caribbean and North American colonies for work in plantation society is beyond compare in the annals of the history of slavery. The Indians and Spaniards had the support and comfort of their families, their kinsfolk, their leaders, and their places of worship in their sufferings. Africans the most uprooted of all, were herded together like animals in a pen, always in a state of impotent rage, always filled with a longing for flight, freedom, change, and always having to adopt a defensive attitude of submission, pretense, and acculturation to the new world.

What characterized the Plantation Church?

Enslaved Africans on plantations “a long ways from home”, remembered home, and the memory of Africa became a controlling metaphor and organizing principle as they countered the hegemonic conditions imposed on them by their masters. There was a tension between their existence on plantations here in the New World and there in Africa, their home of origin. Here in plantation society they longed for there, their home, Africa – the forests, the ancestors, family, Gods and culture. They remembered the forests and they relived their experience of forests through the practice of religious rituals in the brush arbors, often down by the riverside. The memory of ancestors and a sense that their spirits accompanied them served as sites of a new consciousness on the plantations in which the struggle for survival and liberation took precedence. This awakening convinced them that they would survive through running away to the forests or through suicides that would reunite them with families and the Africa they remembered. It was primarily through religious rituals and the carving out of Black sacred spaces that enslaved persons were able to affirm self and create a world over against plantation society which was created for their families by the master. With the creation of the Plantation Church, the African priest and medicine man/woman were able to prevent the enslaved condition from dominating their consciousness and rob the children of Africa the freedom to dream a new world. It was the community’s memory of Africa that provided hope for dreaming the emergence of new worlds whether in Haiti, South Carolina, or Cuba.

Why is the Caribbean so important to the Plantation Church?

There were more than eleven million enslaved persons who were transported across the Black Atlantic and forced to work on plantations in the New World. Of this number, about 450, 000 arrived in the United States and all the rest went south of the border to the Caribbean nations and South America. More than twice the number of Africans who landed in the United States arrived in each of the islands of Haiti, Jamaica, and Cuba. Additionally, it must be noted that slavery began in the Caribbean as early as 1502, well over a hundred years before the first twenty Africans landed in James Town Virginia in 1619. The historical priority and the numerical advantage point to the Black religious experience being born in the Caribbean and not the United States of America. W.E.B. Du Bois puts this in perspective, “American Negroes, to a much larger extent than they realize, are not only blood relatives to the West Indians but under deep obligations to them for many things. For instance, without the Haitian Revolt, there would have been no emancipation in America as early as 1863. I, myself, am of West Indian descent and am proud of the fact.”

Noel Leo Erskine is Professor of Theology and Ethics at Candler School of Theology and the Laney Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Emory University. He has been a visiting Professor in ten schools in six countries. His books include Plantation Church: How African American Religion Was Born in Caribbean Slavery, King Among the Thologians, and From Garvey to Marley.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Plantation Church: a Q&A with Noel Erskine appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 1/1/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade historical fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Krista Russell,

African-American kids,

Best Books of 2013,

2013 middle grade fiction,

2013 historical fiction,

African-American books,

multicultural,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

slavery,

multicultural fiction,

African-American history,

Add a tag

The Other Side of Free

The Other Side of Free

By Krista Russell

Peachtree Publishers

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-56145-710-6

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Have you ever read the adult book How I Became a Famous Novelist? Bear with me for a second here, I know what I’m doing. You see, in the title the author decides that he wants to become a New York Times bestseller. In the course of his quest he runs across a variety of different authors who embody a variety of different types of novels. His own aunt decides she wants to be a children’s author and sets about doing so by writing a work of historical middle grade fiction. The book is about a girl living in Colonial America who wants to be a cooper. In only a page or two author Steve Hely puts his finger on a whole swath of children’s books that drive librarians like myself mildly mad. They find familiar situations and alter very little aside from location and exact year to tell their tales. The result is an increasing wariness on my part to read any works of historical fiction, for fear that you’ll see the same dang story again and again. With all this in mind you can imagine the relief with which I read Krista Russell’sThe Other Side of Free. Not only is the setting utterly original (not to mention unforgettable) but the characters don’t fill the same little roles you’ll see in other children’s novels. If you have kids that have tired of the same old, same old, The Other Side of Free will give them something they haven’t seen before.

We’ve all heard of how slaves would escape to the North when they wished to escape for good. But travel a bit farther back in time to the early 18th century and the tale is a little different. At that point in history slaves didn’t flee north but south to Spain’s territories. There, the Spanish king promised freedom for those slaves that swore fidelity to the Spanish crown and fought on his behalf against the English. 13-year-old Jem is one of those escaped slaves, but his life at Fort Mose is hardly stimulating. Kept under the yoke of a hard woman named Phaedra, Jem longs to fight for the king and to join in the battles. But when at last the fighting comes to him, it isn’t at all what he thought it would be. A Bibliography of sources appears at the end of the book.

There are big themes at work here. What freedom is worth to an individual if it means yoking yourself to someone else. If militia work really does mean freedom, or just slavery of a new kind. Jem himself chafes under the hand of Phaedra, though I think it would be obvious, even to a kid reader, that he’s immature in more than one way. But with all that said, it’s the lighter moments that make the book for me. Omen the owl is a notable example of a detail that makes the book more than just a work of history. In this story Jem adopts an owlet and raises it as his own. In your standard generic fare the owl would be a beloved friend and companion, possibly ultimately dying for Jem in a heroic scene reminiscent of Hedwig’s death. Instead, the owl is hell on wings. A nasty, chicken-snatching, very real and wild creature that is, nonetheless, beloved of our hero. Again, expectations are upset. I love it when that happens.

I liked the individual lines Russell used to dot the text as well. For example, in an early character note about Phaedra the book describes her construction of a grass basket. “Her fingers snatched at the fronds again and again, until each strip was bent and shaped to her will.” It’s worth noting that it’s Jem who is saying this about her. Almost the whole book is told through his own perspective and, as such, may not be entirely trustworthy. He has his own prejudices to fight, after all. I also like Russell’s everyday descriptions. “Adine handed each man a jug of water. They drank until it ran down their faces, leaving tails like gray veins down their throats.” Beautifully put.

Honestly it would make a heckuva stage play. The settings are necessarily limited, with Jem spending most of his time in Fort Mose and the rest of it in St. Augustine. Not having been familiar with the people of Fort Mose before, I found myself incredibly anxious to learn what became of them. Russell ends the book on a hopeful note, but you cannot help but wonder. If there were freed slaves in Florida in 1739 then what happened when that state became the property of the English in 1763? All Russell says at that time is “At this time, the free Africans of Mose relocated to Cuba.” Kids will just have to extrapolate a happy ending for Jem and his friends from that.

A great work of historical fiction does a number of things. It introduces you to unfamiliar places and people. It establishes a kind of empathy for those people that you otherwise would never have met. It puts you in their shoes, if only for a moment. And most of all, it surprises you. Upsets your expectations, maybe. For most kids in America, the history of slavery is short and sweet. Slaves came from Africa. They escaped North. They were freed thanks in part to the Civil War. What more is there is say or to learn aside from some vague info on the Underground Railroad? Russell challenges these assumptions, bringing us a tale that is wholly new, but filled with facts. If the rote and familiar don’t suit you and you want a book that travels over new ground, you can hardly do better than The Other Side of Free. Smart and original, it’s a one-of-a-kind novel. Hardly the kind of thing you run across every day.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Notes on the Cover: I don’t want to sound ungrateful. I can see what Peachtree was going for here. In this image you get the dense canopy of a Floridian forest. You even have a black boy on the cover (albeit completely turned away from the viewer, which is kind of a cheat). But all in all, whether it’s the art or the design or the color palette, this book is not the most visually appealing little number I’ve seen in all my livelong days. I’m having a devil of a time getting folks to pick it up of their own accord. One hopes that if it goes to paperback someday, maybe it’ll be given a cover worthy of its content.

Like This? Then Try:

Tonight marks the first night of Passover, so I thought I’d share a bit about what the holiday celebrates and what it means to me. Passover is one of the most important Jewish holidays of the year, and is probably the most observed Jewish holiday after Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur (despite what people think about Hanukah!).

Passover commemorates the story of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, as told in the old testament (or, if you’re the kind of person who waits for the movie to come out, as told in The Ten Commandments). According to the story, the Israelites were enslaved in Egypt for 400 years, until God, with the help of Moses, led them out of Egypt and into freedom.

Whether or not you believe in God or the Old Testament, the Passover story resonates. For me, one of the most meaningful parts of it is the acknowledgement of how truly terrible and traumatic slavery is: terrible enough that, although Jews were slaves many thousands of years ago, we still recall the experience in great detail every year. We even eat bitter herbs during the seder, the traditional Passover meal, so that the bitter taste of slavery is fresh on our tongues.

Unfortunately, slavery is not ancient history; in fact, it’s alive and well in many parts of the world. Whether enslaved by law, by force, or by poverty, many human beings living on earth today are not free. Passover is a time to really meditate on what that means – and, perhaps, on our part in it. What have I done to support or abolish slavery? Am I buying from companies with good labor practices? Am I aware of what’s happening in my own community? Are there sustainable ways of dismantling slavery that I can support?

Although slavery is a heavy subject, I actually think it’s one that young people can really understand deeply, and Passover is a great time to explore it together. Over at Pinterest, we’ve rounded up some books for children about Passover and/or freedom. These books are great ways to start a discussion with young readers about slavery, both ancient and modern.

Another resource I’ll be thinking about a lot this year is a documentary I saw last week called Girl Rising, by the organization 10 x 10. The documentary focuses on the stories of ten girls from around the world and shows that for many young women, the passage from slavery to freedom is an education. Definitely worth watching, and suitable for children 12 and up. Taking kids to a screening near you would be a great way to celebrate the holiday.

If you have other slavery/freedom related resources for young people, feel free to leave them in the comments. And to all those who are celebrating tonight, I wish you all a very happy (and meaningful) Passover!

Further Reading:

What does Ramadan celebrate?

What does Chinese New Year celebrate?

Filed under:

Holidays Tagged:

Cambodia,

freedom,

Girl Rising,

holidays,

Jewish,

passover,

slavery

The Lightning Dreamer. Margarita Engle. 2013. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 182 pages.

Books are door-shapedportalscarrying meacross oceansand centuries,helping me feelless alone.But my mother believesthat girls who read too muchare unladylikeand ugly,so my father's books are lockedin a clear glass cabinet. I gazeat enticing coversand mysterious titles,but I am rarely permittedto touchthe enchantment of words. (3)

I definitely enjoy Margarita Engle's verse novels. Her newest is a verse novel about Cuban abolitionist poet, Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda, who was nicknamed Tula. For a young girl--a young woman--who dreamed so big, wanted so much, her environment was quite oppressive. Her family wanted, NEEDED, her to marry well. But. Tula had different ideas. She held onto the notion that she could have ideas of her own:

Girls are not supposed to think,

but as soon as my eager mind

begins to race, free thoughts

rush in

to replace

the trapped ones. (4)

Tula discovers a whole new world within the convent library, and once she begins her journey, there will be no dissuading her...

Opinions.

Ideas.

Possibilities.

So many!

How can I choose?

Between bursts

of lightning-swift energy,

I enjoy peaceful moment

when the whole world

seems to be a flowing river

of verse

and all I have to do is learn

how to swim.

During those times,

I find it so easy to forget

that I'm just a girl who is expected

to live

without thoughts. (41)

The novel is rich and descriptive. I love the writing...

"I feel certain that words

can be as human

as people,

alive

with the breath

of compassion." (26)

So many people

have not yet learned

that souls have no color

and can never

be owned. (69)

Love is as tricky as a wall

of mirrors that make

narrow hallways

seem open

and wide. (146)

I would definitely recommend this one!

Read The Lightning Dreamer

- If you enjoy verse novels

- If you enjoy historical novels based on real people and events

- If you enjoy Margarita Engle's works

- If you are looking for YA books set in Cuba

© 2013 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By:

keilinh,

on 2/28/2013

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

biography,

nonfiction,

painting,

black history month,

slavery,

don tate,

overcoming obstacles,

Musings & Ponderings,

It Jes' Happened,

bill traylor,

dreams and aspirations,

African American interest,

united states history,

Add a tag

Everyone knows Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King, Jr., but there are many other African Americans who have contributed to the rich fabric of our country but whose names have fallen through the cracks of history.

We’ve asked some of our authors who chose to write biographies of these talented leaders why we should remember them. We’ll feature their answers throughout Black History Month.

Today, Don Tate shares why he wrote about Bill Traylor in It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started to Draw:

Bill Traylor was an “outsider artist.” He learned to draw in much the same way that I learned to paint: by trial and error. He taught himself to draw. Somehow I felt an immediate kinship to Bill. In his day, Bill’s art sold for about 10- to 25-cents and was panned by art critics as “primitive.” Today Bill’s art is collected by top art connoisseurs, and is on display in museums all over the world, selling for thousands of dollars. I love these kinds of stories where the “outsider” gets the glory.

Bill had an inborn – I believe God-given – talent that came forth in time of great need. That spoke to me, too. It supported my belief that all people are born equipped with everything needed to overcome great obstacles in life and do great things.

I think it’s important for children to be exposed to a variety of historical figures. Black history is not limited to the one or two people that are so often written and published about. In addition to civil rights, African Americans have made great contributions to science and technology, arts and literature, sports and entertainment, education and business. Bill Traylor was an artist, but he was also a journalist, though he may not have realized it. And a historian, too.Through his art, he documented an important part of American history that will be appreciated for many hundreds of years to come.

Further reading:

Black History Month: Why Remember Florence “Baby Flo” Mills?

Black History Month: Why Remember Robert Smalls?

Black History Month: Why Remember Toni Stone?

Black History Month: Why Remember Arthur Ashe?

Black History Month Book Giveaway

Filed under:

Musings & Ponderings Tagged:

African American interest,

bill traylor,

biography,

black history month,

don tate,

dreams and aspirations,

It Jes' Happened,

nonfiction,

overcoming obstacles,

painting,

slavery,

united states history

Hard to believe that 2013 has arrived – here’s hoping for a peaceful and kind year for the world – a hope in vain I know.

One of the things I am looking forward to this year is the publication of my next book, a sequel to The Butterfly Heart. This one is called The Sleeping Baobab Tree and in its honour here is (yet another) picture of this wondrous tree of life.

This picture is taken in Bagamoyo in Tanzania. The meaning of Bagamoyo in KiSwahili is ‘Lay Down your Heart’ and the reason it is called this is that it had become, by the late eighteenth Century, a major slave trading post. Arab slave traders would bring slaves in from the interior to Bagamoyo and from there they would be shipped to the slave markets and plantations of Zanzibar. It was here that slaves would lay down their hearts to leave them behind as their bodies were transported away from home for the last time.

Slaves came from far and wide in the interior and it was calculated that for every one slave who reached Bagamoyo there were ten who died along the way. For all of them who did reach the port this would have been their first view of the wide blue Indian Ocean – an ocean that would serve only to carry them in the holds of trading ships towards lives of brutality and hardship. Dr. Livingstone at the time said of the slave trade in East Africa (as it was then) that ‘to overdraw its evils is simply not possible’

This Baobab will have borne witness to that evil – it now looks out on a kinder place.

The Bagamoyo Baobab in full leaf

In 2009 on their album Bang the Drum, Mango Groove released a song that my brother had written (with the help of my father who provided the Swahili) for use during a human rights campaign in South Africa. The song is called Bagamoyo and while unfortunately there is no video of it available, here are the lyrics.

BAGAMOYO (Lay Down Your Heart)

Kurudi, Nyumbani

Nathulisa Umoyo

The day you left I was a stranger to you

The air was still the sky was grey

A pale moon led you through a starless night

A quiet sea took you away

Now time is not enough to do the healing

And words are not enough to heal your pain

But together maybe we can find a different space

A secret place where all our memories remain

So lay down your heart for me

Be strong and set me free

Walk away but still remain

Change it all but stay the same

And don’t forget a world within is a world apart

So lay down your heart

In dreams you’ll walk along a different path

The morning air will taste so sweet

You’ll lift your face towards blue African skies

You’ll feel her earth beneath your feet

As evening falls you’ll reach a different place

Where a warm December wind whispers your name

And as you look out from the shores of Bagamoyo

A million stars will know you came

Because like you they’ve come home again

So lay down your heart for me

Be strong and set me free

Walk away but still remain

Change it all but stay the same

And don’t forget a world within is a world apart

So lay down your heart

Kurudi, Nyumbani

Nathulisa Umoyo

It was nearly five years from proposal to publication, but now I'm finally holding Master George's People in my hot little hands. To say I'm pleased with how it turned out is an understatement—I'm over the moon! Lori Epstein's stunning photographs are a big reason why. So is the beautiful, powerful design created by National Geographic's Jim Hiscott. Both were true collaborators on this project. Back in June, I wrote in INK about our photo shoot with Lori at Mount Vernon, George Washington's Virginia plantation. Today I asked Jim if he would share with us his process of designing the book.

What look and feel were you striving for with the cover?

Jim:

The initial design construct, at least in regard to the typography, came from the idea of broadsides used for the search and capture of runaway slaves, utilizing a blocky and distressed typography. In fact in the title, "Master George's People," there are two different styles that work in concert with each other, one an extended serif font and the other a condensed stencil style. The counterpoint to this is the use of a more elegant and refined condensed serif display font for the subtitle and the large cap indents that launch each chapter. The use of the distressed rules on the cover and the interior was another reference to newspapers and a graphic approach of the period. How about the inside of the book? The little decorative doodads at the end of the picture captions have a colonial feel to me. Were you aiming to create a sense of period with this and other design elements?

Jim:

The overall design tenet I always use, no matter the style, is to create contrasts between things, elements, no matter what they may be, as a way to create energy, impact, and tension. For this book I wanted to reflect the contrast between these two worlds—that of George Washington and the refined manners of the day compared to the life of slaves. Hard/soft if you will. And by using color on the cover as well as on the inside, it was a way to be respectful of the NGKids brand while also trying to create a look that was respectful of two periods of time—present day and the Colonial period. This all helped to give the book a certain dynamic that allowed me to present it in a strong, elegant, and sophisticated manner that hopefully feels contemporary as well.

What were the challenges of designing a book illustrated with so many different kinds of images, from archival illustrations to historical documents to reenactment photography? (By the way, the photo above was taken by yours truly and does NOT do justice to the real thing.)

Jim:

I know this kind of thing always causes some trepidation from the editorial side of a project. However, I look at having to rely on a diversity of visual images/styles to flesh out a visual story as an asset. Given the challenges of finding images to represent different points of the story, to me, only makes it visually richer, especially when they are framed with the use of photography of reenactments. When you speak of HISTORY many people aren't going to think of it as very interesting. I want to try to create a visual package that helps make the book engaging on one level so it is appealing for the reader to then get absorbed into the story. It also helps to have a captivating manuscript.Why thank you, Jim. Is there anything else you'd like to share about designing

Master George's People?Jim:

I loved working on this book. It was a true pleasure to be able to try and package it in a way that was respectful of the period and the story, while trying to make it visually appealing to today's readers, and to create a sophisticated book that kids would want to read, as if something really special had been created especially for them. Yes, it is a very serious topic, but that doesn't mean it can't be presented in an attractive and sophisticated way that is clean, fresh, and hopefully not so trendy as to become dated. You want a design that has as long a shelf life as possible.Many thanks to Jim for giving us a glimpse into his creative process. And my personal thanks to him for helping me tell the story of George Washington and the people he held in bondage.

|

| Left to right: Jennifer Emmett (my wonderful editor), me, Jim Hiscott (art director and designer) and Hillary Moloney (illustrations assistant) at Mount Vernon. Missing is photographer Lori Epstein. She's behind the lens! |

By: shelf-employed,

on 6/4/2012

Blog:

Shelf-employed

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

history,

book review,

nonfiction,

slavery,

Civil War,

Non-Fiction Monday,

Abraham Lincoln,

Frederick Douglass,

Advance Reader Copy,

Add a tag

Freedman, Russell. 2012.

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The date is August 10, 1863. Frederick Douglass has arrived at the White House, taking a seat on the stairs, determined to speak with President Lincoln. Many others are waiting as well. Douglass stands out in the crowd, not just for his size. All the other petitioners are White. Douglass, a freed Black is an outspoken critic of Lincoln. The two men have never met. Douglass has no appointment. He is prepared to wait.

He does not wait long, however. The President

does see Frederick Douglass on August 10, 1863; and in

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American Friendship, award-winning author, Russell Freedman tells us why.

Freedman is a master writer, and ingeniously sets up this story of friendship. Chapter One, "Waiting for Mr. Lincoln," sets the stage. The next three chapters detail the life of Frederick Douglass before his meeting with Lincoln. Three subsequent chapters do the same for the President. The final three chapters highlight the collaboration of the two men in pursuit of their mutual interest, abolition.

The extensive use of period photographs and artwork, as well as images of period realia (election poster, paycheck, editorial cartoons and the like) add interest to an already compelling story. The depth of Lincoln's regard for Douglass is cemented by the revelation that Mary Todd Lincoln sent Douglass a memento after Lincoln's death, knowing that Lincoln had "wanted to do something to express his warm personal regard" for Douglass.

Appendix:

Dialogue Between a Master and Slave, Historic Sites, Selected Bibliography, Notes (on the sources of more than one hundred quotes) and Picture Credits (including many from the Newbery Medal-winning Russell Freedman book,

Lincoln: A Photobiography) round out this extensively researched book.

The Contents page indicates an Index beginning on page 115, however, it was apparently not completed in time for the printing of the Advance Reading Copies.

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglas is suggested for Grades 4-7, and is due on shelves June 19, 2012. It is a fascinating look at two of the most influential men of their time by one of the great children's authors of our time. Highly recommended.

By:

Aline Pereira,

on 5/27/2012

Blog:

PaperTigers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Africa,

slavery,

Cultures and Countries,

Week-end Book Reviews,

weekend book review,

Brave Music of a Distant Drum,

Keilin Huang,

Manu Herbstein,

religious persection in young adult novels,

Add a tag

Manu Herbstein,

Manu Herbstein,

Brave Music of a Distant Drum

Red Deer Press, 2011.

Ages: 16+

There are some stories that touch you and some that change you. This is what Kwame Zumbi discovers after a visit with his blind mother. Initially turned off by her physical condition and what Kwame sees as a sinful lifestyle (she refuses to call him by his Christian name and she doesn’t attend a Christian church), he eventually learns of a past that he has long forgotten and indeed that he has chose to forget. Ama has a story to tell, one that “lies within me, kicking like a child in the womb” and she summons her son, Kwame, to write it down as she dictates to him. Kwame is impatient with Ama and finds her “old and blind…unwell and…ugly,” but as her story unfolds, he realizes just how amazing her journey has been. From Ama’s comfortable beginnings in her hometown to her relationship with a Dutch governor that brought her across foreign waters to the hardships she faced while on the English slave ship, The Love of Liberty, Kwame learns not only about his earlier life, but ultimately just how powerful and influential his mother’s story can be.

Award-winning author, Manu Herbstein, blends fact with fiction to create a rich story that not only tells a heartwrenching and powerful tale of friendship, love, and loss, but also chonicles the history of the trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the scars that it has left behind. The topics found in Brave Music of a Distant Drum can be hard to read about (rape, cruel and unusual punishment, religious persecution), but Herbstein uses the calm and steady voice of Ama to serve as a means of “introduc[ing] a new generation of readers to this history and encourage them to broaden their knowledge of it.” In this way, readers learn about a different, often forgotten, aspect of slavery’s history.

Eventually, the reader realizes that Kwame has been the “blind” one and only when Ama comes to the end of her story does he realize the true strength of family. Herbstein doesn’t give the story a tidy ending, but instead, he ends on a realistic note. In this way, he is encouraging the reader to continue the conversation on a “taboo” subject by asking questions or doing their own research.

Brave Music of a Distant Drum is an amazing story that gives a deep, and sometimes difficult, account of the slave trade. It’s not an understatement to say that Herbstein’s tale is a vital part of history and a key to understanding cross-cultural relations today.

Keilin Huang

May 2012

By: Stacy A. Nyikos,

on 4/4/2012

Blog:

Stacy A. Nyikos

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Kimberly Brubaker Bradley,

Jefferson's Son,

Ellen's Broom,

history,

slavery,

founding fathers,

Thomas Jefferson,

Sally Hemings,

Kelly Starling Lyons,

Add a tag

Jefferson's Sons - A Founding Father's Secret ChildrenKimberly Brubaker Bradley

Grades 6 - 9

Brubaker Bradley brings to life the story of the four children - Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston - that researchers have, after much prodding, historical research and DNA analysis, acknowledged Thomas Jefferson had with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings.

Brubaker Bradley's story begins through the eyes of Beverly Jefferson, the eldest of the four children who survived into adulthood, and follows the story through Madison Jefferson, the middle son, and finally, Peter Fossett, the son of the blacksmith, Joe Fossett, who was sold after Jefferson's death.

It is told from close third from just one character's POV at a time. When Beverly becomes a teenager, Brubaker makes an ingenious transition from his POV to Madison's. So much so, my ten year old exclaimed, "Mama, it's Maddy's story now!" It was like a magic trick that the audience sees but still marvels at. Brubaker Bradley is a pro. I learned a few new tricks.

The story revolves around family. In this particular case, a mother, Sally, who was a slave, yet became, for all intents and purposes, the second wife of Thomas Jefferson after his first wife died. And a father, Thomas Jefferson, who wrote all men were created equal yet kept his own children as slaves. And four children who were the slaves and children of one of the United States' most revered but, as we learn through walking in these children's shoes, hypocritical founding fathers.

Brubaker Bradley spent three years working on this book. It shows. She has taken so much material and blended it so seamlessly. The story is suffused with childhood, slavery, history, philosophy, politics, historical figures. They all come to life.

My youngest daughter and I listened to the audio of this book while in DC and Charlottesville for Spring Break. About halfway through the book, we went to Monticello, Jefferson's home. My daughter's been there before, but it hadn't stuck. This time, though, the home wasn't just one more historical building we walked through. My daughter looked for traces of Hemmings' family members, and Fossetts and Hearns. History wasn't boring. It was alive and had faces. It was so cool. We even listened to a part of the story while sitting on a bench on Mulberry Row, where the slave quarters were at Monticello. Afterwards, when we were listening to

Jefferson's Sons again in the car, my daughter said over and over, "oh, yeah", as she remembered the places that were a part of the story.

This is a book you don't want to miss. The writing is superb. The subject matter begs to be discussed. And the last scene is unforgettable.

Read it.

There are so many excellent books that have come out for children that take historical facts and weave them into fiction that breathes with life. Another, for slightly younger readers, that embraces an African American wedding tradition, jumping the broom, that is inherently tied to slavery but may actually predate it is

Ellen's Broom by Kelly Starling Lyons.

I've never been much of a history fan, until now. Through these two books, I feel as if I've discover

Qualls’s primitive-style collage illustrations strongly convey the depth of Brown’s emotions.-School Library Journal,

0 Comments on Much has happened in the past few months... as of 3/7/2012 7:18:00 AM

Good Fortune by Noni Carter, Simon and Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2010, 496 pp, ISBN: 1416984801

Recap:Ayanna was taken from her home, from her mother, in Africa when she was only four years old. Good Fortune traces her life's journey from the slave ship, through years on a southern plantation, and then across the country in her search for freedom.

Review:I initially picked up Good Fortune because I read a synopsis and it sounded so much like one of my favorites: Copper Sun by Sharon Draper. Plus, that cover is just gorgeous.

After reading all 496 pages... I think I'd just as soon have re-read Copper Sun. Yes, Ayanna (who becomes Sarah who becomes Anna) is a protagonist to admire. She is strong, courageous, and wants to be educated more than almost anything in the world. She is the embodiment of perseverance. Her story even has a little romance which, in my opinion, makes any good book better.

But I just couldn't help thinking that her story had already been told. There were many passages that just seemed redundant, and there wasn't a single surprise over the course of Anna's journey. In all fairness, the last few pages could have been a great surprise, but I felt like author Noni Carter had left plenty of foreshadowing hints along the way.

I do think that Noni Carter's journey toward publication was pretty phenomenal! She started writing pieces of what would become Good Fortune when she was only 12-years-old. She sold the manuscript to Simon and Schuster at BEA 2008, and they published it in 2010. Ms. Carter is only 19-years-old! That is just flat out amazing. While Good Fortune may not be my new favorite book, I do think we will see great things from Noni Carter in the years to come.

Recommendation:Good Fortune will appeal to readers who really enjoy historical fiction. That being said, I would eagerly recommend Copper Sun by Sharon Draper, 47 by Walter Mosley, or Numbering All the Bones by Ann Rinaldi to readers who are looking for a truly engrossing story about slavery. 47 is actually just as much science fiction as it is historical fiction; how's that for a twist?

The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books - Freedom Song: The Story of Henry “Box” Brown; illus. by Sean Qualls. Harper/HarperCollins, 2012 32p ISBN 978-0-06-058310-1 $17.99 R* 5-8yrs Ellen Levine and Kadir Nelson’s Henry’s Freedom Box (BCCB 4/07) sets the bar high for picture books about the Virginia slave who endured pummeling confinement in a crate as he had himself shipped to New York and freedom. Walker, inspired by the discovery that Henry Brown sang for many years in a church choir, takes a more poetic but equally successful tack, imagining that rhythm and song sustained Brown throughout his years of enslaved labor and inspired him to seek his freedom when his wife and children were sold away from Virginia. Walker infuses her text and Brown’s thoughts with patterned phrasing, from the “twist, snap, pick-a-pea” work songs he sang in the fields, to the “freedom-land, family, stay-together words” that comforted him as a child, to the “stay-still, don’t move, wait-to-be-sure words” that kept him silent as he waited for release from his shipping crate. Qualls’ mixed-media illustrations, far more dreamy and stylized than Nelson’s near-photorealistic renderings, are nonetheless an excellent match for Walker’s text. Even his signature aquas and pinks, embellished with free-floating bubbles, are tempered with more sober grays, browns, and deep blues, and weighted with heavily textured brushwork. An author’s note touches on Walker’s research and what little is known of Brown’s subsequent history; also appended is the fascinating text of a letter from Brown’s accomplice in 1849, detailing Brown’s escape and cautioning the recipient, “for Heaven’s sake don’t publish this affai or allow it to be published. It would . . . prevent all others from escaping in the same way.” EB

.jpeg?picon=3604)

By:

Katie DeKoster,

on 2/21/2012

Blog:

Book Love

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Pura Belpre Honor,

Cuba,

poetry,

historical fiction,

slavery,

women's history,

PoC,

fearless female,

multicultural lit,

Add a tag

The Firefly Letters: A Suffragette's Journey to Cuba by Margarita Engle, Henry Holt and Co, 2010, 160 pp, ISBN: 0805090827

Recap:Fredricka Bremer - Swedish suffragette, novelist, and humanitarian - traveled to Cuba in the hope of discovering a modern-day Eden. Instead, she found an island of contrasts: sparkling, tropical waters carrying boats full of children in chains; lush, vibrant landscapes that Cuban women were not free to explore, or even learn about.

Together with Cecelia, the slave girl who was her interpreter, and Elena, her wealthy host's daughter, Fredrika tells the tale of the Cuba that she experienced - both the ugly and the beautiful.

Review:Novel in verse: yay! Multiple narrators: double yay! These are two of my favorite writing techniques, and I believe that they elevated this extremely short story into something more like art.

The Firefly Letters is a sleek little novel - I think it only took me about a half hour to read cover to cover - but the themes that it tackles are huge: slavery, gender roles, education, and classism. Whew. Real life suffragette Fredricka Bremer traveled to Cuba in 1851. Author Margarita Engle was able to use Bremer's letters, sketches, and diary entries from that time period in order to write The Firefly Letters. Bremer was shocked and dismayed to find that slaves, some as young as eight-years-old, populated much of the island. On top of that, she protested against the limited rights and educational opportunities that were afforded to free Cuban women and girls. In The Firefly Letters, the other two narrators - Cecelia and Elena, are both confused and delighted by Bremer's "radical" ideas concerning freedom and women's rights.

For me, Elena never became a very "real" character. Instead, she seemed more like a generic representative of all girls born into privilege on the island. And maybe that was because she was a product of Engle's imagination, while Cecelia was actually based on a real person - a young slave girl who Bremer described in her diary. Cecelia was clearly extremely intelligent; she could speak multiple languages and because of her skill as a translator, she was one of the most valuable slaves on the plantation. I imagine that her interactions with Bremer had a life-changing effect, and I hope that her baby was able to grow up as a free person.For all of the weight behind this novel's history, it is truly a simply told story. It could easily be used in a classroom as part of a study o