new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: folk and fairy tale reviews, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: folk and fairy tale reviews in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/10/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

fairy tales,

Best Books,

Lisbeth Zwerger,

folk and fairy tale reviews,

German children's books,

minedition,

translated picture books,

Anthea Bell,

Best Books of 2016,

Reviews 2016,

2016 folk and fairytales,

2016 translated children's books,

Wilhelm Hauff,

Add a tag

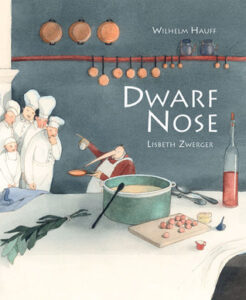

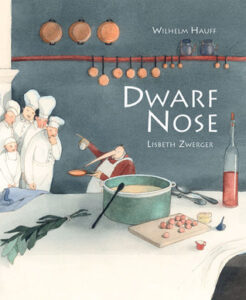

Dwarf Nose

Dwarf Nose

By Wilhelm Hauff

Illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger

Translated by Anthea Bell

Minedition

$19.99

ISBN: 97898888341139

Ages 8-12

On shelves April 1st

It seems so funny to me that for all that our culture loves and adores fairytales, scant attention is paid to the ones that can rightfully be called both awesome and obscure. There is a perception out there that there are only so many fairytales out there that people really need to know. But for every Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty you run into, there’s a Tatterhood or Riquet with the Tuft lurking on the sidelines. Thirty or forty years ago you’d sometimes see these books given a life of their own front and center with imaginative picture book retellings. No longer. Folktales and fairytales are widely viewed by book publishers as a dying breed. A great gaping hole exists, and into it the smaller publishers of the world have sought to fulfill this need. Generally speaking they do a very good job of bringing world folktales to the American marketplace. Obscure European fairytales, however, are rare beasts. How thrilled I was then to discover the republication of Wilhelm Hauff and Lisbeth Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose. Originally released in America in 1995 by North-South books, the book has long been out-of-print. Now the publisher minedition has brought it back and what a beauty it is. Strange and sad and oddly uplifting, this tale has all the trappings of the fairytales you know and love, but somehow remains entirely unexpected just the same.

For there once was a boy who lived with his two adoring parents. His father was a cobbler and his mother sold vegetables and herbs in the market. One day the boy was assisting his mother when a very strange old woman came to them and starting digging her dirty old hands through their wares. Incensed, the boy insulted the old woman, which as you may imagine didn’t go down very well. When the boy is made to help carry the woman’s purchases back to her home he is turned almost immediately into a squirrel and made to work for seven years in her kitchen. After that time he awakes, as if in a dream, only to find seven years have passed and his body has been transformed. Now he has no neck to speak of, a short frame, a hunched back, and a extraordinarily long nose. Sad that his parents refuse to acknowledge him as their son, he sets forth to become the king’s cook. And all would have gone without incident had he not picked up that enchanted goose in the market one day. Written in 1827 this tale is famous in Germany but remains relatively obscure in the United States today.

I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus.

I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus.

We like it when our fairytales give us nice clear-cut morals. Be clever, be kind, be good. This may be another reason why Dwarf Nose never really took off in the States. At first glance one would assume that the moral would be about not judging by appearances. Dwarf Nose’s parents cannot comprehend that their beautiful boy is now ugly, and so they throw him out. He gets a job as a chef but does not search out a remedy until the goose he rescues gives him some hope. I was fully prepared for him to remain under his spell for the rest of his life without regrets, but of course that doesn’t happen. He’s restored to his previous beauty, he returns to his parents who welcome him with open arms, and he doesn’t even marry the goose girl. Hauff ends with a brief mention of a silly war that occurred thanks to Dwarf Nose’s disappearance ending with the sentence, “Small causes, as we see, often have great consequences, and this is the story of Dwarf Nose.” That right there would be your moral then. Not an admonishment to avoid judging the outward appearance of a thing (though Dwarf Nose’s talents drill that one home pretty clearly) but instead that a little thing can lead to a great big thing.

When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one.

When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one.

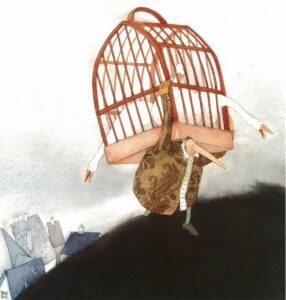

Lisbeth Zwerger is a fascinating illustrator with worldwide acclaim everywhere except, perhaps, America. It’s not that her art feels too “foreign” for U.S. palates, necessarily. I suspect that as with the concerns with the length of Dwarf Nose, Zwerger’s art is usually seen as too interstitial for this amount of text. We want more art! More Zwerger! I’ve read a fair number of her books over the years, so I was unprepared for some of the more surreal elements of this one. In one example the witch Herbwise is described as tottering in a peculiar fashion. “…it was as if she had wheels on her legs, and might tumble over any moment and fall flat on her face on the paving stones.” For this, Zwerger takes Hauff literally. Her witch is more puppet than woman, with legs like bicycle wheels and a face like a Venetian plague doctor. We have the slightly unnerving sensation that the book we are reading is, in fact, a performance put on for our enjoyment. That’s not a bad thing, but it is unexpected.

When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

On shelves April 1st.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Misc: Check out this fantastic review of the same book by 32 pages.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/29/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Neil Gaiman,

Reviews,

fairy tales,

Hansel and Gretel,

folk and fairy tale reviews,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 folk and fairytales,

Add a tag

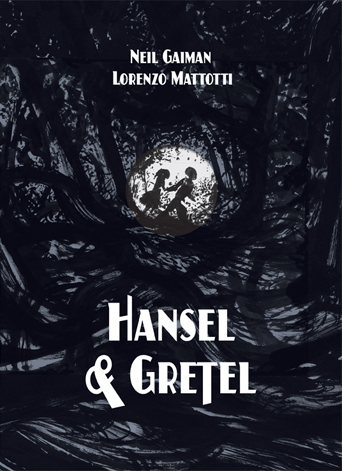

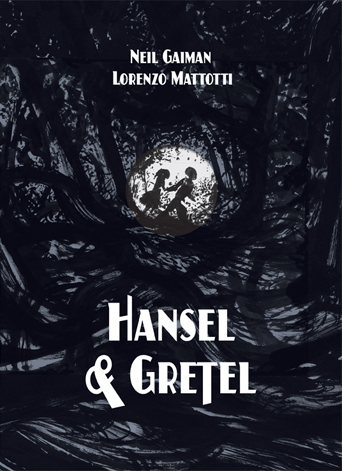

Hansel and Gretel

Hansel and Gretel

By Neil Gaiman

Illustrated by Lorenzo Mattotti

Candlewick

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-935179-62-7

Ages 6 and up

When a successful writer of books for adults decides to traipse headlong into the world of children’s literature, the results are too often disastrous. From Donald Barthelme’s self-indulgent Slightly Irregular Fire Engine to the more recent, if disastrous in an entirely different way, Rush Revere series by Rush Limbaugh, adult authors have difficulty respecting the unique perspective of a child reader. Either they ignore the intended audience entirely and appeal to the parents with the pocket change or they dumb everything down and reduce the storytelling to insulting pabulum. This is not to say that all adult authors are unsuccessful. Sylvia Plath penned the remarkable The Bed Book while Ted Hughes brought us The Iron Giant. Louise Erdrich will forever have my gratitude for her Birchbark House series and while I wouldn’t call Michael Chabon’s Summerland a roaring success, it at least had some good ideas. Then we come to Neil Gaiman. Mr. Gaiman is one of those rare adult authors to not only find monetary success in the field of children’s books but literary success as well. His The Graveyard Book won the prestigious Newbery Award, given once a year to the most distinguished written book of children’s literature in America. Like Donald Hall with his Ox-Cart Man, Gaiman has successfully straddled two different literary forms. Unlike Hall, he’s done so repeatedly. His latest effort, Hansel and Gretel takes its inspiration from art celebrating an opera. It is, in an odd way, one of the purest retellings of the text I’ve had the pleasure to read. A story that begs to be spoken aloud, even as it sucks you into its unnerving darkness.

In the beginning there was a woodcarver and his pretty wife and their two children. Times were good and once in a while the family, though never rich, would get a bite of meat. Then the wars came and the famine. Food became so scarce that the wife persuaded her husband to abandon their children in the woods. The first time he tried to do so he failed. The second time he succeeded. And when Hansel and Gretel, the children in question, spotted that gingerbread cottage with its barley sugar windows and hard candy decorations the rest, as they say, was history.

It’s a funny kind of children’s book. The bulk of it is text-based, with time taken for Mattotti’s black and white two-paged spreads between the action. For people expecting a standard picture book this can prove to be a bit unnerving. Yet the truth is that the book begs to be read aloud. I can see teachers reading it to their classes and parents reading it to their older children. The art is lovely but it’s practically superfluous in the face of Gaiman’s turn of phrase. Consider sentences like “They slept as deeply and as soundly as if their food had been drugged. And it had.” There’s something deeply satisfying about that “And it had”. It is far more chilling in its matter-of-factness than if Gaiman had ended cold with “It had”. The “And” gives it a falsely comforting lilt that chills precisely because it sounds misleadingly comforting. It pairs very well with the first sentence in the next section: “The old woman was stronger than she looked – a sinewy, gristly strength…” He then peppers the books with little tiny nightmares that might not mean much on a first reading but are imbued with their own small horrors if you pluck them out and look at them alone. The witch’s offers to Gretel to make her one of her own and teach her how to ensnare travelers. Hansel’s refusal to let go of the bone that saved his life, even after the witch has died. And the final sentence of the book has a truly terrible tone to it, though on the surface it appears to be nothing but sunshine and light:

It’s a funny kind of children’s book. The bulk of it is text-based, with time taken for Mattotti’s black and white two-paged spreads between the action. For people expecting a standard picture book this can prove to be a bit unnerving. Yet the truth is that the book begs to be read aloud. I can see teachers reading it to their classes and parents reading it to their older children. The art is lovely but it’s practically superfluous in the face of Gaiman’s turn of phrase. Consider sentences like “They slept as deeply and as soundly as if their food had been drugged. And it had.” There’s something deeply satisfying about that “And it had”. It is far more chilling in its matter-of-factness than if Gaiman had ended cold with “It had”. The “And” gives it a falsely comforting lilt that chills precisely because it sounds misleadingly comforting. It pairs very well with the first sentence in the next section: “The old woman was stronger than she looked – a sinewy, gristly strength…” He then peppers the books with little tiny nightmares that might not mean much on a first reading but are imbued with their own small horrors if you pluck them out and look at them alone. The witch’s offers to Gretel to make her one of her own and teach her how to ensnare travelers. Hansel’s refusal to let go of the bone that saved his life, even after the witch has died. And the final sentence of the book has a truly terrible tone to it, though on the surface it appears to be nothing but sunshine and light:

“In the years that followed, Hansel and Gretel each married well, and the people who went to their weddings ate so much fine food that their belts burst and the fat from the meat ran down their chins, while the pale moon looked down kindly on them all.”

Some versions of the story turn the mother into a stepmother, for what kind of parent would sacrifice her own children for the sake of her own skin? Here Gaiman is upfront about the mother. She was pretty once but became bitter and sharp-tongued in time. It’s her plying words that convince the woodcutter to go along with the abandonment plan. As the book later explains, subsequent version of this tale turned her into a stepmother, but here we’ve the original parent with her original sin. Gaiman also solves some problems in the plot that had always bothered me about the story. For example, why does Hansel drop white stones that are easy to follow the first time he and Gretel are abandoned in the woods but breadcrumbs the second? The answer is in the planning. Hansel has foreknowledge of his mother’s wicked scheme the first time around and has time to find the stones. The second time the trip into the woods catches him unawares and so the only thing he has on hand to use for a path are the breadcrumbs of the food he’s given for lunch.

Originally the illustrations in this book were created by Lorenzo Mattotti for the Metropolitan Opera’s staging of the opera of the same name. These pieces of art (which the publication page says are in “a rich black ink, on a smooth woodfree paper from Japan”) proved to be the inspiration for Gaiman’s take. This is no surprise. Mattotti knows all too well how to conjure up the impression of light or night with the merest swoops of his paintbrush. His children are no better than silhouettes. Does it even matter if they have any features? Here the trees are the true works of art. There’s something hiding in the gloom here and from the vantage taken, the thing lurking in the woods, spying upon the kids, is ourselves. We are the eyes making these two children so very nervous. We espy their mother pacing in front of their home just before the famine starts. We peer through the trees at the kids crossing past a small gap in the trunks. On a first glance the shadows are universal but then you notice when Mattotti chooses to imbue a character with features. The children are left abandoned in the woods and all you can see of the woodcutter is an axe and an eye. I think it the only eyeball in the entire book. It’s grotesque.

Originally the illustrations in this book were created by Lorenzo Mattotti for the Metropolitan Opera’s staging of the opera of the same name. These pieces of art (which the publication page says are in “a rich black ink, on a smooth woodfree paper from Japan”) proved to be the inspiration for Gaiman’s take. This is no surprise. Mattotti knows all too well how to conjure up the impression of light or night with the merest swoops of his paintbrush. His children are no better than silhouettes. Does it even matter if they have any features? Here the trees are the true works of art. There’s something hiding in the gloom here and from the vantage taken, the thing lurking in the woods, spying upon the kids, is ourselves. We are the eyes making these two children so very nervous. We espy their mother pacing in front of their home just before the famine starts. We peer through the trees at the kids crossing past a small gap in the trunks. On a first glance the shadows are universal but then you notice when Mattotti chooses to imbue a character with features. The children are left abandoned in the woods and all you can see of the woodcutter is an axe and an eye. I think it the only eyeball in the entire book. It’s grotesque.

Of course, for a children’s librarian the best part might well be the backmatter. Recently I read a version of “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” that suggested that the Grimm tale was a metaphor for a plague that had wiped out all of Hamelin’s children, save a few. A similar theory surrounds “Hansel and Gretel”, suggesting that the story’s origins lie in the Great Famine of 1315. Further information is given about the tale, ending at last with the current iteration and (oh joy!) a short Bibliography. You might not be as ready to nerd out over this classic fairy tale, but for those of you with a yen, boy are you in luck!

What is the role of a fairy tale these days? With our theaters and books filled to brimming with reimagined tellings, one wonders what fairy tales mean to most people. Are they cultural touchstones that allow us to speak a universal language? Do they still reflect our deepest set fears and worries? Or are they simply good yarns worth discovering? However you chose to view them, the story of “Hansel and Gretel” deserves to be plucked up, shaken out like an old coat, and presented for the 21st century young once in a while. Neil Gaiman’s a busy man. He has a lot to do. He could have phoned this one in. Instead, he took the time and energy to make give the story its due. It’s not about what we fear happening to us. It’s about what we fear doing to ourselves by doing terrible things to others. The fat from the meat is running down our chins. Best to be prepared when something comes along to wipe it up.

On shelves now.

Source: Publisher copy sent for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/26/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Best Books,

Aesop's fables,

Karadi Tales,

folktale review,

folk and fairy tale reviews,

picture book folktales,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 folk and fairytales,

Culpeo S. Fox,

Manasi Subramaniam,

Add a tag

The Fox and the Crow

The Fox and the Crow

By Manasi Subramaniam

Illustrated by Culpeo S. Fox

Karadi Tales

$17.95

ISBN: 978-81-8190-303-7

Ages 4 and up

On shelves now

In the classic Aesop fable of The Fox and the Crow where do your loyalties lie? You remember the tale, don’t you? Long story short (or, rather, short story shorter) a prideful crow is tricked into dropping its bread into the hungry mouth of a fox when it is flattered into singing. Naturally your sympathies fall with the fox to a certain extent. Pride goeth before the bread’s fall and all that jazz. Now there are about a thousand different things that are interesting about The Fox and the Crow, a collaboration between Manasi Subramaniam and Culpeo S. Fox. Yet the thing that I took away from it was how my sympathies fell, in the end, to the prideful crow victim. His is a miserable existence, owed in part due to his own self-regard and also to not seizing the moment when it presents itself. Delayed gratification sometimes just turns into no gratification. Lofty thoughts for a book intended for four-year-olds, eh? But that’s what you get when something as lovely, dark, and strange as this particular The Fox and the Crow hits the market. Gorgeous to eye and ear alike, the story’s possibilities are mined beautifully and the reader is left reeling in the wake. If you’d like a folktale that’s bound to wake you up, this beauty has your number.

A murder of crows gathers on the telephone wires. Says the text “When dusk falls, they arrive, raucous, clamping their feet on the wires in a many-pronged attack.” One amongst them, however, cannot help but notice a fresh loaf of new bread at the local bakery. Without another thought it dives, steals the bread, and leaves the baker angrily yelling in its wake. Delighted with its prize the crow takes to a tree branch to wait. “Bread is best eaten by twilight.” Below, a hungry fox observes the haughty crow and desires the tasty morsel. She sings up to the crow. “A song is an invitation. Crow must sing back.” He does and, in doing so, loses his prize to the vixen’s maw. The last line? “A new day breaks. An old hunger aches.”

Turning Aesop fables into full picture books is a bit of an art. If you read one you’ll find that it’s remarkably short on the page. It requires a bit of padding on the author’s part. Either that or some true creativity. Look, for example, at some of the best Aesop adaptations out there. Some artists choose to go wordless (The Lion and the Mouse by Jerry Pinkney). Others get remarkably loquacious (Lousy Rotten Stinkin’ Grapes by Margie Palatini). In the case of Subramaniam, she makes the interesting choice of simplifying the text with long, luscious words while expanding the story. The result is lines like “Crow’s stomach burns with swallowed song” or “Oh, she’s a temptress, that one.” No dialogue is necessary in this book. Subramaniam shoulders all the work and though she doesn’t spell out what’s happening as simply as some might prefer (you have to know what is meant by “Crow’s pride sets his hunger ablaze” to get to the classic Aesopian moral of the tale) it’s nice to see a new take on a story that’s been done to death in a variety of different spheres.

Artist Culpeo S. Fox is new to me. From Germany (for some reason everything made a lot more sense when I learned that fact) the man sort of specializes in foxes. For this book the art takes on a brown and speckled hue. Early scenes look as though the very dirt of the ground was whipped into the air alongside the crows’ wings. Yet in the midst of all this darkness (both from the story and from the art) there’s something incredibly relatable and kid-friendly in these creatures’ eyes. The crow in particular is rendered an infinitely relatable fellow. From his first over-the-shoulder glance at the bread cooling on the windowsill to the look of pure eagerness when he alights on a private branch. It’s telling that the one moment the eye is made most unrelatable (pure white) is when he’s overcome with fury at having basically handed his loaf to the fox’s maw. Fury can be frightening.

It’s also Fox’s inclination to change from a horizontal to a vertical format over and over again that makes the book unique in some way. It’s probably the element that will turn the most people off, but it’s never done without reason. To my mind, if a book is going to go vertical, it needs to have a reason. Caldecott Honor book Tops and Bottoms by Janet Stevens, for example, knew exactly how to make use of the form. Parrots Over Puerto Rico in contrast seemed to do it on a lark rather than for any particular reason. In The Fox and the Crow each vertical shift is calculated. The very first encounter between the fox and the crow is a vertical shot. Most interesting is the next two-page spread. You find yourself not entirely certain what the best way to hold book might be. Horizontal? Vertical? Upside down? Only after a couple readings did I realize that the curve of the crow’s inquiry-laden neck echoes the fox’s very same neck curve (albeit with 75% more guile).

It’s also Fox’s inclination to change from a horizontal to a vertical format over and over again that makes the book unique in some way. It’s probably the element that will turn the most people off, but it’s never done without reason. To my mind, if a book is going to go vertical, it needs to have a reason. Caldecott Honor book Tops and Bottoms by Janet Stevens, for example, knew exactly how to make use of the form. Parrots Over Puerto Rico in contrast seemed to do it on a lark rather than for any particular reason. In The Fox and the Crow each vertical shift is calculated. The very first encounter between the fox and the crow is a vertical shot. Most interesting is the next two-page spread. You find yourself not entirely certain what the best way to hold book might be. Horizontal? Vertical? Upside down? Only after a couple readings did I realize that the curve of the crow’s inquiry-laden neck echoes the fox’s very same neck curve (albeit with 75% more guile).

It’s not just the art and the story. The very size of the book itself is unique. It’s roughly 11 X 12 inches, essentially a rather large square. Work with enough picture books and you get a feel for the normal dimensions. But normal dimensions, you sense, wouldn’t quite encompass was Fox is trying to accomplish here. You need size to adequately tell this story. The darkness and beauty of it all demand it.

I am consumed with professional jealousy after reading the Kirkus review of this book. Their takeaway line? “Aesop noir”. It’s rather perfect, particularly when you consider that one reading of this book would fall under that classic noir storyline of a seedy soul done in by the wiles of a woman. Or vixen, rather. I don’t know that any younger kids would necessarily take to heart the moral message of the original story, but slightly older readers will jive to what Subramaniam is getting at. We need folktales in our collections that shake things up a bit. That aren’t afraid to get original with the source material. That aren’t afraid to get, quite frankly, beautiful on us. The pairing of Subramaniam and Fox is inspired and the book a lush treat. An Aesop necessity. Aesop done right.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- Fables by Aesop, illustrated by Jean-Francois Martin

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/12/2011

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

picture book reviews,

Bloomsbury,

Poly Bernatene,

Jonathan Emmett,

folk and fairy tale reviews,

Summer 2011 books,

2011 picture books,

2011 reviews,

Best Books of 2011,

Walker & Company,

Add a tag

The Princess and the Pig

The Princess and the Pig

By Jonathan Emmett

Illustrated by Poly Bernatene

Walker & Co. (a division of Bloomsbury)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-8027-2334-5

Ages 4-8

On shelves now

The princess craze is a relatively new phenomenon. I’m sure that little girls have pretended to be princesses for as long as the occupation has existed, but the current concentrated capitalization on that desire has taken the obsession to a whole other level. You can’t enter a toy department these days without being bombarded with the idea that every little girl should wear pink, frilly, sparkly costumes and woe betide the child that might prefer a good unadorned set of overalls instead. Naturally, all this sank into the world of picture books after a while. Stories like The Paper Bag Princess were now being ignored while the latest pink monstrosity would suck up all the attention. So you can probably understand why I was a little reluctant to pick up The Princess and the Pig at first. My first instinct was to just throw it on the pile with the rest of the princessey fare. Fortunately, I heard some low-key buzz about the book, making it clear that there might be something worthwhile going on here. Thank goodness I did too. Ladies and gentlemen, two men have come together and somehow produced a book that thumbs its nose at the notion of a little girl wanting to be a princess. In fact, when it comes right down to it, this is a tale about how sometimes it’s difficult to tell the royalty from the swine. Now that’s a lesson I can get behind!

The day the queen didn’t notice that she dropped her baby daughter off of the castle’s battlements could have been horrific. Instead, it led to a case of switched identities. When a kindly farmer parks his cart beneath a castle so as to take a break, he doesn’t notice when a flying baby lands in the cart and launches upward the cart’s former inhabitant, baby piglet. The piglet lands in the baby’s bassinet and the queen, seeing a change in her daughter, is convinced that an evil fairy must be to blame. Meanwhile the baby, dubbed Pigmella, is promptly adopted by the kindly farmer and his wife. She grows up to love her life while Princess Priscilla, a particularly porcine royal, pretty much just acts like a pig. Years later the farmer and his wife figure out the switcheroo but when they attempt to right a great wrong they are rebuffed by the haughty royals. So it is that Pigmella gets to marry a peasant and avoid the chains of royalty while Priscilla has a wedding of her own . . . poor handsome prince.

Normally I exhibit a strong aversion to self-referential fairy tales. You know the ones I mean. The kinds of stories that act like the Shrek movies, winking broadly at the parents every other minute whether it serves the story or not. And certainly “The Princess and the Pig” never forgets for a second that it is operating in a fairytale land. The king in the queen in this book have a way of using fairytales to justify their already existing expectations and prejudices, constantly holding them up as the solution to their every problem. Rather than feel forced, the royals’ silliness is utterly consistent with their characters. It was only after I reread the book that I realized that while they are under the distinct impression that every problem beg

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 8/25/2011

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Uncategorized,

slavery,

Patricia McKissack,

multicultural children's literature,

multicultural picture books,

folktale review,

folk and fairy tale reviews,

picture book folktales,

2011 picture books,

2011 reviews,

Best Books of 2011,

2012 Caldecott contender,

Diane Dillon,

Leo Dillon,

Schwartz & Wade,

2011 folktales,

Add a tag

Never Forgotten

Never Forgotten

By Patricia C. McKissack

Illustrated by Leon and Diane Dillon

Schwartz & Wade

$18.99

ISBN: 978-0-375-84384-6

Ages 4 and up

On shelves October 11, 2011

The more I read children’s literature the more I come to realize that my favorite books for kids are the ones that can take disparate facts, elements, and stories and then weave them together into a perfect whole. That someone like Brian Selznick can link automatons and the films of Georges Melies in The Invention of Hugo Cabret or Kate Milford can spin a story from the history of bicycles and the Jake Leg Scandal in The Boneshaker thrills me. Usually such authors reserve their talents for chapter books. There they’ve room to expound at length. And Patricia McKissack is no stranger to such works of fiction. Indeed some of her chapter books are the best in a given library collection (I’ve a personal love of her Porch Lies). But for Never Forgotten Ms. McKissack took tales of Mende blacksmiths and Caribbean legends of hurricanes and combined them into a picture book. Not just any picture book, mind you, but one that seeks to answer a question that I’ve never heard adequately answered in any books for kids: When Africans were kidnapped by the slave trade and sent across the sea, how did the people left behind react? The answer comes in this original folktale. Accompanied by the drop dead gorgeous art of Leo & Diane Dillon, the book serves to remind and heal all at once. The fact that it’s beautiful to both eye and ear doesn’t hurt matters much either.

When the great Mende blacksmith Dinga found himself with a baby boy after his wife died he bucked tradition and insisted on raising the boy himself. For Musafa, his son, Dinga called upon the Mother Elements of Earth, Fire, Water and Wind and had them bless the child. Musafa grew in time but spent his blacksmithing on creating small creatures from metal. Then, one day, Dinga discovers that Musafa has been kidnapped by slave traders in the area. Incensed, each of the four elements attempts to help Dinga get Musafa back, but in vain. Finally, Wind manages to travel across the sea. There she finds Musafa has found a way to make use of his talent with metal, creating gates in a forge like no one else’s. And Dinga, back at home, is comforted by her tale that his son is alive and, for all intents and purposes, well.

McKissack’s desire to give voice to the millions of parents and families that mourned the kidnapping of their children ends her book on a bittersweet note. After reading about Musafa’s disappearance and eventual life, the book finishes with this: “Remember the wisdom of Mother Dongi: / ‘Kings may come and go, / But the fam

McKissack’s desire to give voice to the millions of parents and families that mourned the kidnapping of their children ends her book on a bittersweet note. After reading about Musafa’s disappearance and eventual life, the book finishes with this: “Remember the wisdom of Mother Dongi: / ‘Kings may come and go, / But the fam

Dwarf Nose

Dwarf Nose I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus.

I go back and forth when I consider why this fairytale isn’t all that famous to Americans. There are a variety of reasons. There are some depressing elements to it (kid is unrecognizable to parents, loses seven years of his life, etc.) sure. There aren’t any beautiful princesses (except possibly the goose). The bad guy doesn’t even appear in the second act. Still, it’s the peculiarities that give it its flavor. We’ve heard of plenty of stories where the heroes are transformed by the villains, but how many villains give those same heroes a useful occupation in the process? It’s Dwarf Nose’s practicalities that are so interesting, as are the nitty gritty elements of the tale. I love the use of herbs particularly. Whether the story is talking about Sneezewell or Bellyheal, you get the distinct feeling that you’re listening to someone who knows what they’re talking about. Plus there are tiny rodent servants. That’s a plus. When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one.

When this version of Dwarf Nose was originally released in the States in 1994 the reviews were puzzled by its length. Booklist said it was “somewhat verbose to modern listeners” and School Library Journal noted the “grotesque tenor of the book”. Fascinatingly this is not the only incarnation of this tale you might find in America. In 1960 Doris Orgel translated a version of “Dwarf Long-Nose” which was subsequently illustrated by Maurice Sendak. The School Library Journal review of Zwerger’s version in 1994 suggested that the Sendak book was infinitely more kid-friendly than hers. I think that’s true to a certain extent. You get a lot more pictures with the Sendak and the book itself is a much smaller format. While Zwerger excels in infinitely beautiful watercolors, Sendak’s pen and inks with just the slightest hint of orange for color are almost cartoonish in comparison. What I would argue then is that the intended age of the audience is different. Sure the text is remarkably similar, but in Zwerger’s hands this becomes a fairytale for kids comfortable with Narnia and Hogwarts. I remember as a tween sitting down with my family’s copy of World Tales by Idries Shah as well as other collected fairytales. Whether a readaloud for a fourth grade class, an individual tale for the kid obsessed with the fantastical, or bedtime reading for older ages, Dwarf Nose doesn’t go for the easy audience, but it does go for an existing one. When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

When Zwerger’s Dwarf Nose came out in 1994 it was entering a market where folktales were on the outs. Still, libraries bought it widely. A search on WorldCat reveals that more than 500 libraries currently house in on their shelves after all these years. And while folktale sections of children’s rooms do have a tendency to fall into disuse, it is possible that the book has been reaching its audience consistently over the years. It may even be time for an upgrade. Though it won’t slot neatly into our general understanding of what a fairytale consists of, Dwarf Nose will find its home with like-minded fellows. Oddly touching.

The Sendak/Orel edition was one of my favorite books as a child. Still have it. Glad to see this new interpretation by another fairy tale master.