new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: best books of 2015, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 41

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: best books of 2015 in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

.jpg?picon=590)

By:

Little Willow,

on 1/8/2016

Blog:

readergirlz

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

young adult fiction,

Christopher Golden,

YA fiction,

Little Willow,

courtney sheinmel,

sarah dessen,

Tom Sniegoski,

martha brockenbrough,

courtney summers,

best books of 2015,

sara bareilles,

Add a tag

From Becs & Andye!

This is the first year that Reading Teen has participated in the end of year survey (Thanks for the kick in the butt, Becca! Becca: You're welcome! :D), and it's been a lot of fun (Becca: and also, HARD. Did she mention this survey is HARD?!) to fill out and reminisce! We'd love to hear what your favorites of the year were! Hope you find something here that resonates with

Happy New Year!!

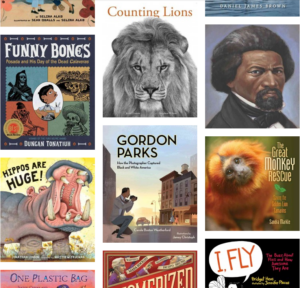

As with each and every year, I like to make my own little list of 100 children’s book titles. These are pretty much for my own reference in the future, though you’re more than welcome to critique the choices as you prefer. Previous lists can be found for 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, and 2010. And, as always, you’ll note that this isn’t a “Best Books” list but rather just a listing of books I personally found magnificent. ONWARD!

100 Magnificent Children’s Books 2015

Board Books (new category!)

If You’re a Robot and You Know It by Musical Robot. Illustrated by David Adler

Picture Books (For Children Ages 2-6)

Beep! Beep! Go to Sleep! by Todd Tarpley. Illustrated by John Rocco

Bernice Gets Carried Away by Hannah E. Harrison

Betty Goes Bananas by Steve Antony

Billy’s Booger by William Joyce

Boats for Papa by Jessixa Bagley

Drum Dream Girl: How One Girl’s Courage Changed Music by Margarita Engle. Illustrated by Rafael Lopez

Everybody Sleeps (But Not Fred) by Josh Schneider

Fire Engine No. 9 by Mike Austin

Float by Daniel Miyares

The Fly by Petr Horacek

Hoot Owl, Master of Disguise by Sean Taylor. Illustrated by Jean Jullien

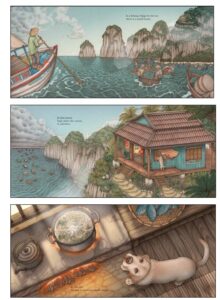

In a Village By the Sea by Muon Van. Illustrated by April Chu

Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Pena. Illustrated by Christian Robinson

Moletown by Torben Kuhlmann

The Moon is Going to Addy’s House by Ida Pearle

The Night World by Mordicai Gerstein

Mr. Squirrel and the Moon by Sebastian Meschenmoser

One Day, The End: Short, Very Short, Shorter-Than-Ever Stories by Rebecca Kai Dotlich. Illustrated by Fred Koehler

Oskar and the Eight Blessings by Richard Simon and Tanya Simon. Illustrated by Mark Siegel

The Potato King by Christoph Niemann

Raindrops Roll by April Pulley Sayre

Red: A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall

The Red Hat by David Teague. Illustrated by Antoinette Portis

Red, Yellow, Blue (And a Dash of White Too) by C.G. Esperanza

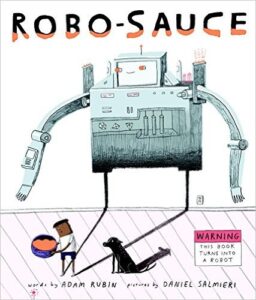

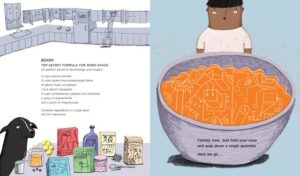

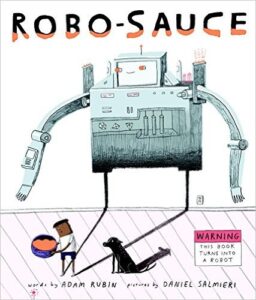

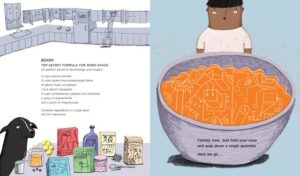

Robo-Sauce by Adam Rubin. Illustrated by Daniel Salmieri

Sidewalk Flowers by Jonarno Lawson. Illustrated by Sydney Smith

Snow White and the Seventy-Seven Dwarfs by Davide Cali. Illustrated by Raphaelle Barbanegre

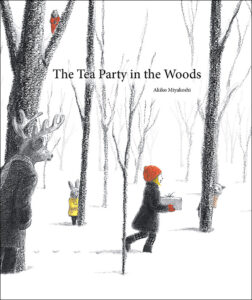

The Tea Party in the Woods by Akiko Miyakoshi

Tell Me What to Dream About by Giselle Potter

This Is Sadie by Sara O’Leary. Illustrated by Julie Morstad

Water is Water: A Book About the Water Cycle by Miranda Paul. Illustrated by Jason Chin

When Otis Courted Mama by Kathi Appelt. Illustrated by Jill McElmurry

The Whisper by Pamela Zagarenski

Wolfie the Bunny by Ame Dyckman. Illustrated by Zachariah OHora

A Wonderful Year by Nick Bruel

Folktales and Fairy Tales

The Hare and the Hedgehog by The Brothers Grimm. Illustrated by Jonas Lauströer

Maya’s Blanket: La Manda de Maya by Monica Brown. Illustrated by David Diaz

The Most Wonderful Thing in the World by Vivian French. Illustrated by Angela Barrett

Mousetropolis by R. Gregory Christie

One the Shoulder of a Giant: An Inuit Folktale by Neil Christopher. Illustrated by Jim Nelson

Poetry

Beastly Verse by Joohee Yoon

A Great Big Cuddle: Poems for the Very Young by Michael Rosen. Illustrated by Chris Riddell

Hypnotize a Tiger: Poems About Just About Everything by Calef Brown

Lullaby and Kisses Sweet: Poems to Love With Your Baby, selected by Lee Bennett Hopkins. Illustrated by Alyssa Nassner

The National Geographic Book of Nature Poetry, edited by J. Patrick Lewis

Over the Hills and Far Away: A Treasury of Nursery Rhymes, collected by Elizabeth Hammill

Sail Away by Langston Hughes. Illustrated by Ashley Bryan

Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer, Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement by Carole Boston Weatherford. Illustrated by Ekua Holmes

Stories for Younger Readers

Buckle and Squash: The Perilous Princess Plot by Sarah Courtauld (ill?)

The Day No One Was Angry by Toon Tellegen. Illustrated by Marc Boutavant

Don’t Throw It to Mo! by David Adler. Illustrated by Sam Ricks

Dory and the Real True Friend by Abby Hanlon

The First Case by Ulf Nilsson. Illustrated by Gitte Spee

Hamster Princess: Harriet the Invincible by Ursula Vernon

The Story of Diva and Flea by Mo Willems. Illustrated by Tony DiTerlizzi

Stories for Older Readers

The Astounding Broccoli Boy by Frank Cottrell Boyce

Castle Hangnail by Ursula Vernon

Circus Mirandus by Cassie Beasley

Dragon’s Guide to the Care and Feeding of Humans by Lawrence Yep

Echo by Pam Munoz Ryan

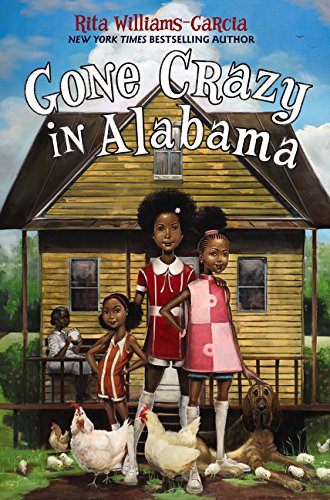

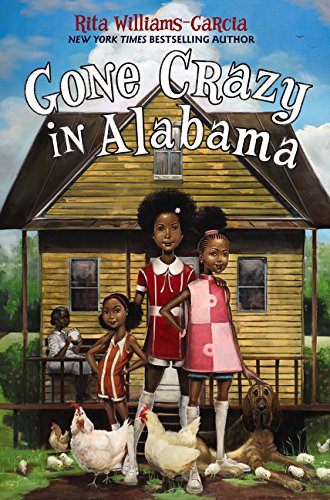

Gone Crazy in Alabama by Rita Williams-Garcia

Goodbye, Stranger by Rebecca Stead

The Imaginary by A.F. Harrold. Illustrated by Emily Gravett

The Jumbies by Tracey Baptiste

Lilliput by Sam Gayton. Illustrated by Alice Ratteree

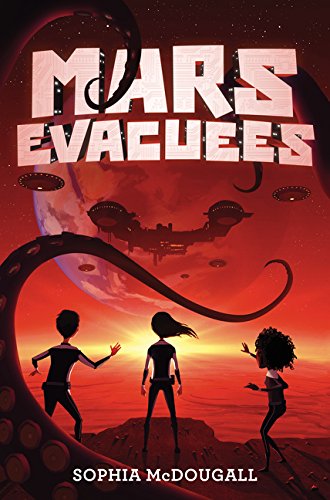

Mars Evacuees by Sophia McDougall

The Marvels by Brian Selznick

Masterminds by Gordon Korman

MiNRS by Kevin Sylvester

My Near-Death Adventures (99% True!) Alison DeCamp

A Nearer Moon by Melanie Crowder

The Nest by Kenneth Oppel. Illustrated by Jon Klassen

Penderwicks in Spring by Jeanne Birdsall

A Question of Miracles by Elana K. Arnold

The Sign of the Cat by Lynne Jonell

The Terrible Two by Mac Barnett and Jory John. Illustrated by Kevin Cornell

Tiger Boy by Mitali Perkins. Illustrated by Jamie Hogan

Unusual Chickens for the Exceptional Poultry Farmer by Kelly Jones. Illustrated by Katie Kath

The War that Saved My Life by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley

Graphic Books

Baba Yaga’s Assistant by Marika McCoola. Illustrated by Emily Carroll

Hilo: The Boy Who Crashed to Earth by Judd Winick

Human Body Theater by Maris Wicks

Lost in NYC by Najda Spiegelman. Illustrated by Sergio Garcia Sanchez

Nathan Hale’s Hazardous Tales: The Underground Abductor by Nathan Hale

The Only Child by Guojing

Roller Girl by Victoria Jamieson

Rutabaga: The Adventure Chef by Eric Colossal

Space Dumplings by Craig Thompson

Nonfiction

28 Days: Moments in Black History That Changed the World by Charles R. Smith Jr. Illustrated by Shane Evans

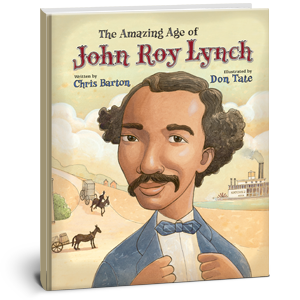

The Amazing Age of John Roy Lynch by Chris Barton. Illustrated by Don Tate

The Case for Loving: The Fight for Interracial Marriage by Selina Alko. Illustrated by Sean Qualls

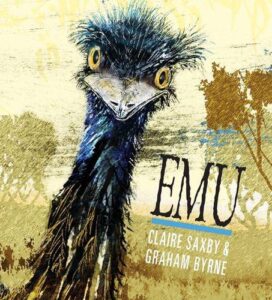

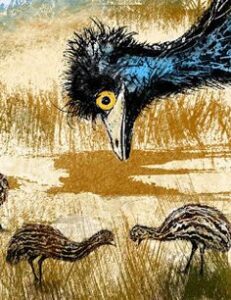

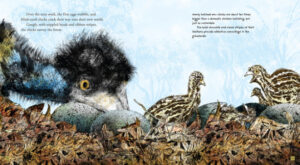

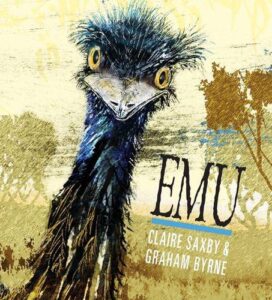

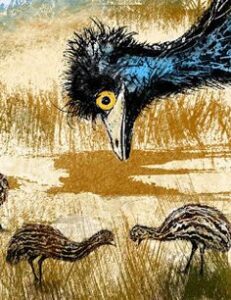

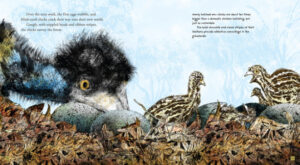

Emu by Claire Saxby. Illustrated by Graham Byrne

Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear by Lindsay Mattick. Illustrated by Sophie Blackall

Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras by Duncan Tonatiuh

Gordon Parks: How the Photographer Captured Black and White America by Carole Boston Weatherford. Illustrated by Jamey Christoph

I, Fly by Bridget Heos. Illustrated by Jennifer Plecas

Mesmerized: How Ben Franklin Solved a Mystery That Baffled All of France by Mara Rockliff. Illustrated by Iacopo Bruno

Rhythm Ride: A Road Trip Through the Motown Sound by Andrea Davis Pinkney

Tricky Vic: The Impossibly True Story of the Man Who Sold the Eiffel Tower by Greg Pizzoli

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/27/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Kids Can Press,

Best Books,

picture book reviews,

Japanese children's literature,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

2015 reviews,

Akiko Miyakoshi,

Japanese imports,

Reviews,

Add a tag

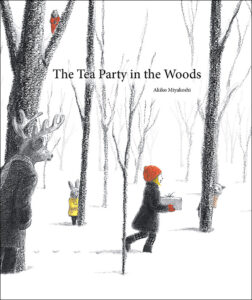

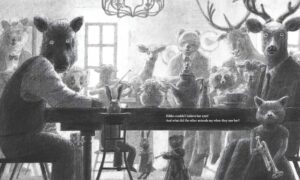

The Tea Party in the Woods

The Tea Party in the Woods

By Akiko Miyakoshi

Kids Can Press

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1771381079

Ages 3-6

There are picture books out there that feel like short films. Some of the time they’re adapted into them (as with The Snowman or The Lost Thing or Lost and Found) and sometimes they’re made in tandem (The Fantastic Flying Books of Morris Lessmore). And some of the time you know, deep in your heart of hearts, that they will never see the silver screen. That they will remain perfect little evocative pieces that seep deep into the softer linings of a child’s brain, changing them, affecting them, and remaining there for decades in some form. The Tea Party in the Woods is like that. It looks on first glance like what one might characterize to be a “quiet” book. Upon further consideration, however, it is walking the tightrope between fear and comfort. We are in safe hands from the start to the finish but there’s no moment when you relax entirely. In this strangeness we find a magnificent book.

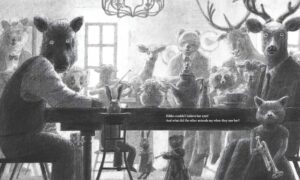

Having snowed all night, Kikko’s father takes off through the woods to shovel out the walk of her grandmother. When he forgets to bring along the pie Kikko’s mother baked for the occasion, Kikko takes off after him. She knows the way but when she spots him in the distance she smashes the pie in her excitement. Catching up, there’s something strange about her father. He enters a house she’s never seen before. Upon closer inspection, the man inside isn’t a man at all but a bear. A sweet lamb soon invites Kikko in, and there she meets a pack of wild animals, all polite as can be and interested in her. When she confesses to having destroyed her grandmother’s cake, they lend her slices of their own, and then march her on her way with full musical accompaniment.

Part of what I like so much about this book is that when a kid reads it they’re probably just taking it at face value. Girl goes into woods, hangs out with clothed furry denizens, and so on, and such. Adults, by contrast, are bringing to the book all sorts of literary, cinematic, and theatrical references of their own. A girl entering the woods with red on her head so as to reach her grandmother’s reeks of Little Red Riding Hood (and I can neither confirm nor deny the presence of a wolf at the tea party). The story of a girl wandering into the woods on her own and meeting the wild denizens who live there for a feast makes the book feel like a best case fairy encounter scenario. In this light the line, “You’re never alone in the woods”, so comforting here, takes on an entirely different feel. Some have mentioned comparisons to Alice in Wonderland as well, but the tone is entirely different. This is more akin to the meal with the badgers in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe than anything Lewis Carroll happened to cook up.

Part of what I like so much about this book is that when a kid reads it they’re probably just taking it at face value. Girl goes into woods, hangs out with clothed furry denizens, and so on, and such. Adults, by contrast, are bringing to the book all sorts of literary, cinematic, and theatrical references of their own. A girl entering the woods with red on her head so as to reach her grandmother’s reeks of Little Red Riding Hood (and I can neither confirm nor deny the presence of a wolf at the tea party). The story of a girl wandering into the woods on her own and meeting the wild denizens who live there for a feast makes the book feel like a best case fairy encounter scenario. In this light the line, “You’re never alone in the woods”, so comforting here, takes on an entirely different feel. Some have mentioned comparisons to Alice in Wonderland as well, but the tone is entirely different. This is more akin to the meal with the badgers in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe than anything Lewis Carroll happened to cook up.

Yet it is the art that is, in many ways, the true allure. Kirkus compared the art to both minimalist Japanese prints as well as Dutch still life’s. Miyakoshi does indeed do marvelous things with light, but to my mind it’s the use of color that’s the most impressive. Red and yellow and the occasional hint of orange/peach appear at choice moments. Against a sea of black and white they draw your eye precisely to where it needs to go. That said, I felt it was Miyakoshi’s artistic choices that impressed me most. Nowhere is this more evident than when Kikko  enters the party for the first time, every animal in the place staring at her. It’s a magnificent image. The best in the book by far. Somehow, Miyakoshi was able to draw this scene in such a way where the expressions on the animals’ faces are ambiguous. It isn’t just that they are animals. First and foremost, it seems clear that they are caught entirely unguarded in Kikko’s presence. The animals that had been playing music have stopped mid-note. And I, an adult, looked at this scene and (as I mentioned before) applied my own interpretation on how things could go. While it would be conceivable for Kikko to walk away from the party unscathed, in the hands of another writer she could easily have ended up the main course. That is probably why Miyakoshi follows up that two-page spread (which should have been wordless, but that’s neither here nor there) with an immediate scene of friendly, comforting words and images. The animals not only accept Kikko’s presence, they welcome her, are interested in her, and even help her when they discover her plight (smashing her grandmother’s pie). Adults everywhere who have found themselves unaccompanied (and even uninvited) at parties where they knew no one, and will recognize in this a clearly idyllic, unapologetically optimistic situation. In other words, perfect picture book fodder.

enters the party for the first time, every animal in the place staring at her. It’s a magnificent image. The best in the book by far. Somehow, Miyakoshi was able to draw this scene in such a way where the expressions on the animals’ faces are ambiguous. It isn’t just that they are animals. First and foremost, it seems clear that they are caught entirely unguarded in Kikko’s presence. The animals that had been playing music have stopped mid-note. And I, an adult, looked at this scene and (as I mentioned before) applied my own interpretation on how things could go. While it would be conceivable for Kikko to walk away from the party unscathed, in the hands of another writer she could easily have ended up the main course. That is probably why Miyakoshi follows up that two-page spread (which should have been wordless, but that’s neither here nor there) with an immediate scene of friendly, comforting words and images. The animals not only accept Kikko’s presence, they welcome her, are interested in her, and even help her when they discover her plight (smashing her grandmother’s pie). Adults everywhere who have found themselves unaccompanied (and even uninvited) at parties where they knew no one, and will recognize in this a clearly idyllic, unapologetically optimistic situation. In other words, perfect picture book fodder.

Translation is a delicate art. Done well, it creates some of our greatest children’s literature masterpieces. Done poorly and the book just melts away from the publishing world like mist, as if it was never there. Because I do not have a final copy of this book in hand, I don’t know if the translator for this book is ever named. Whoever they are, I think they knew precisely how to tackle it. Originally published in what I believe to be Japan, I marvel even now at how the story opens. The first line reads, “That morning, Kikko had awoken to a winter wonderland.” We are plunged into the story in such as way as to believe that we’ve been reading about Kikko for quite some time. It doesn’t say “One morning”, which is a distinction of vast importance. It says “That morning” and we are left to consider why that choice was made. What happened before “That morning” that led up to the events of this particular day? Whole short stories have been conjured from less. I love it.

If none of the reasons I’ve mentioned do it for you, consider this: On the front inside book flap of this book perches a squirrel in a bright red party dress in the crook of a tree. Tiny squirrel. Tiny red flowing gown. A detail you might easily miss the first ten times you read this book but it is there and just makes the book for me. Add in the tone, the light, the mood, and the writing itself and you have a book that will be remembered long after the name has faded from its readers’ minds. Something about this book will stick with your kids for all time. If you want something that feels classic and safely dangerous, Miyakoshi’s book is a rare piece of comfortable animal noir. No one is alone in the woods and after this book no one would want to be.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

The New Yorker writers have selected their favorite books of 2015.

The list includes recommendations from Joshua Rothman, Jennifer Gonnerman, Ben Marcus, Rebecca Mead, Amanda Petrusic, Daniel Mendelsohn, Vinson Cunningham, Elif Batuman, Alexandra Schwartz, Rachel Kushner, Hua Hsu, Judith Thurman, Alexis Okeowo, Lauren Collins, Nick Paumgarten, Carrie Battan, and Ben Lerner.

The list includes 49 book recommendations ranging from fiction and nonfiction to memoirs and graphic novels.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/15/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 poetry,

2015 nursery rhymes,

Reviews,

poetry,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

Chris Riddell,

nursery rhymes,

Michael Rosen,

Add a tag

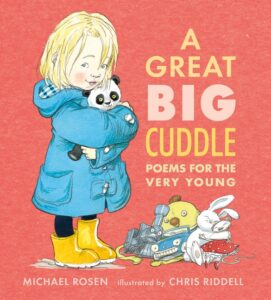

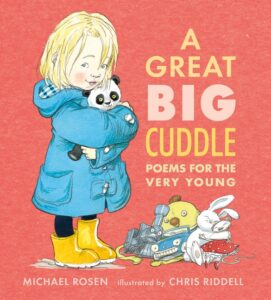

A Great Big Cuddle: Poems for the Very Young

A Great Big Cuddle: Poems for the Very Young

By Michael Rosen

Illustrated by Chris Riddell

Candlewick Press

$19.99

ISBN: 978076368116

Ages 0-4

On shelves now.

Did you know that, generally speaking, Europeans have absolutely no interest in the works of Dr. Seuss? It’s true. For years his works have been untranslatable (though great inroads have been made thanks to some recent Spanish editions) and those that remain in the original English have done very poorly in the United Kingdom. Americans by and large tend to be baffled by this. We look at the British lists of Best Picture Books and the like and find them Seuss-free zones. Abandon Seuss, all ye who enter here. I once asked an overseas friend if she’d ever heard of The Lorax. What she’d heard of was the abominable Danny DeVito movie. It doesn’t bear thinking about. Here in the States we rely heavily on Seuss because he was such a genius when it came to writing rhyming verse for the very youngest of readers. Now I hold in my hands a big, beautiful, thick collection of poetry for the very smallest of fry and I have to face an uncomfortable notion. If indeed the English are capable of producing books this good for kids this young, perhaps they don’t need any Seuss. With Rosen and Riddell pairing in this way, they seem perfectly capable of making remarkable, rhythmic, ridiculously catchy titles of their very own.

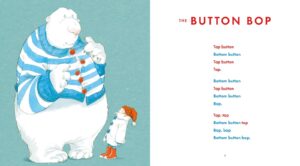

Thirty-five poems greet you. Thirty-five varying in complexity and content. Just to set the tone, the first rhyme is “Tippy-Tappy” and it contains such a catchy rhythm and happy beat that kids will be bouncing in tandem by the time it is done. Next is “The Button Bop”, limited in word count, high on bops. Accompanied by the vibrant watercolors of artist Chris Riddell, each poem aims to set itself apart from the pack. Some are short, and some slightly longer. Some are anxious or scared while others beat their chests and roar their loudest. It feels like there’s something for everyone in this collection, but the takeaway is how well it holds together. A treasure in a treasury.

Michael Rosen isn’t a household name in United States, but I’d say at least one of his books is. Anyone who has ever sought out or read We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, illustrated by Helen Oxenbury has read his words. We’re just nuts about that book, and we have him to thank for it. Despite that, he’s not an author to relegate himself to just one kind of story. Indeed, I haven’t seen him produce much of anything quite as young as “Bear Hunt” in years (or, at the very least, I haven’t seen works of his brought to U.S. shores this “young” in content). That’s why this book is such a surprise and a delight.

If you have a small child, you grow accustomed to the classic nursery rhymes. They have, after all, withstood the test of time. Still, roundabout the one hundred and fortieth time you’ve read “Bye, Baby Bunting” you long for something a little different. Imagine then the palpable sense of relief such a parent might feel when reading jaunty little poems like “What a Fandango!” starring (what else?) a mango. The thing about Rosen is that so many of his poems feel as if they’ve been in the canon of nursery rhymery for centuries. “Oh Dear” is very much in the same vein as “Hush, Little Baby” all thanks to its regular rhythm and repetition. “Party Time” counts down and brings to mind “This Old Man” in reverse. And should you be under the misbegotten understanding that writing poems of this sort is easy, go on. Write one yourself. Now fill a book with them. I’ll just wait right here and finish my sandwich.

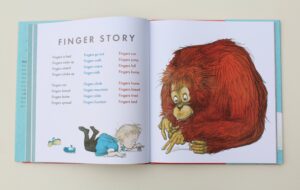

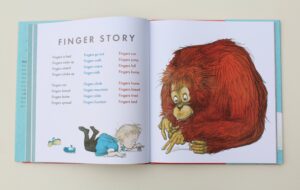

It is also worth noting that without including any verbal instructions, even the dullest of parental readers will catch on pretty early that many of these poems are interactive. Consider “Finger Story” where your fingers are instructed to do everything from “wake up” and “stretch” to “climb” and “slide”. And just in case they’re still not getting it, Chris Riddell’s art is on hand, showing a pudgy youngster and an orangutan of uncommon sweetness walking their fingers together on the ground.

It is also worth noting that without including any verbal instructions, even the dullest of parental readers will catch on pretty early that many of these poems are interactive. Consider “Finger Story” where your fingers are instructed to do everything from “wake up” and “stretch” to “climb” and “slide”. And just in case they’re still not getting it, Chris Riddell’s art is on hand, showing a pudgy youngster and an orangutan of uncommon sweetness walking their fingers together on the ground.

What is interesting to me here is that in terms of age of the reader, Rosen isn’t limiting himself solely to toddlers. There are a couple poems in here that preschoolers would probably appreciate more than their drooling, babbling brethren. “I Am Hungry”, for example, stars a hungry bear listing everything he could eat at this moment (both the usual fare and unusual selections like “A funny joke” or “The sound of yes”) ending with “Then I’ll eat me” which is just the right level of ridiculousness to amuse the canny four-year-old. And “Don’t Squash” is going to ramp up the silly levels pretty effectively when a splatter happy elephant is instructed not to squash her toes, nose, a bun, the sun, cars, stars, a fly, or the very sky.

Now just the slightest glance of a gander at the back bookflap of this book and you’ll get an eyeful of the sheer talent Rosen has been paired with over the years. His words have been brought to life by folks no less eminent than Helen Oxenbury, Quentin Blake, Bob Graham, and more. Truth be told, I don’t really know if this is his first book with Chris Riddell or not. I will say, though, that when I saw that Riddell was the artist on this title I was surprised. When last seen in the States, Riddell had illustrated that nobly intentioned but ultimately awful Russell Brand Pied Piper of Hamlin. Nothing against Riddell, of course, he did what he could with the material (Clockwork Orange Piper and all). So usually when I see his work I associate it with children’s books a bit more on the hardcore side of the equation. Neil Gaiman and Paul Stewart and the like. Could he do adorable? Could he dial back the disgusting? Yes, yes, and (for good measure) yes again. He has that thing we like to call in the business “talent”. Seems to suit him, it does.

Riddell also seems capable of occasionally re-interpreting Rosen’s rhymes with a particularly child-centric view. The poem “Are You Listening?” felt wildly familiar to me, for example. On the left-hand page sits a guilty dinosaur, slurping a piece of spaghetti, looking mildly nervous. On the right-hand page a toddler is berating a small dinosaur stuffed animal, and it will be very easy indeed for kids looking at the picture to extrapolate the relationship between the realistic dino on the left-hand page, and the one on the right. Sometimes I even got the impression that he was softening the content a tad. The poem “Winter” is one of splinters and blisters, but thanks to the gentle hand of Riddell it turns into a snuggly bear hug with mom. All this and he makes the book multicultural as well. Manifique.

Is it very British? With an author from London and an artist from Brighton it runs the risk of indulging in a bit of English chicanery. There wasn’t much that struck me as containing a particular sense of humor, though, with the possible exception of the poem “Once”. A thoroughly silly but darker little work, it will probably remind Yankee readers more of Shel Silverstein than the aforementioned Seuss. There is also “Lost”, the story of a small mouse all alone, without any particular happy resolution in sight. Had such a poem appeared in a collection for small children originally in the States, I don’t think it’s ridiculous to think that an American editor would have gently nudged the author away from ending the poem with the somewhat dire, “I don’t know, I don’t know, anything at all. / I’m going to sit still now and just look at the wall.”

Is it very British? With an author from London and an artist from Brighton it runs the risk of indulging in a bit of English chicanery. There wasn’t much that struck me as containing a particular sense of humor, though, with the possible exception of the poem “Once”. A thoroughly silly but darker little work, it will probably remind Yankee readers more of Shel Silverstein than the aforementioned Seuss. There is also “Lost”, the story of a small mouse all alone, without any particular happy resolution in sight. Had such a poem appeared in a collection for small children originally in the States, I don’t think it’s ridiculous to think that an American editor would have gently nudged the author away from ending the poem with the somewhat dire, “I don’t know, I don’t know, anything at all. / I’m going to sit still now and just look at the wall.”

The least respected form of children’s literature in existence is poetry. It hasn’t any American Library Association awards it can win. It typically is remembered by teachers in April and then never thought of again. But nursery rhymes fare a bit better. Not every parent remembers to read them to their children, but a fair number try. Getting those same parents to read original works of poetry to their little kids can be trickier, so it helps if you package your book as a big, beautiful, lush and gorgeous gift book. Delightful to read aloud again and again (a good thing since I’m afraid you will have to, if only to please your rabid pint-sized audience) and lovely to the eye, Rosen and Riddell aim for the earliest of ages and end up creating a contemporary classic in the process. It may not be Seuss but you won’t miss him while you read it. A necessary purchase for any new parent. A required selection for libraries and bookstores everywhere. Or, as the book puts it, “Tippy-tappy / Tippy-tappy / Tap, tap, tap.”

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Interviews: Chris and Michael speak on the radio about the book. Many fine sketches are to be seen as well.

Videos:

The man himself. Repeatedly.

From Becca's Shelves...

Top Ten Tuesday is hosted by The Broke & The Bookish.

This week's topic is TOP TEN BEST BOOKS I READ IN 2015! which I kind of went overboard with. As one does when chosen for the task of naming the best books of the year. That was the worst task ever! But also fun, remembering the books that took my breath away!

Shutter by Courtney Alameda - Ghost Hunters

Each year New York Public Library produces what I seriously consider to be the most beautiful Best Books list of them all. Encompassing 100 books in total, it breaks all children’s books written in different categories to the following: Picture Books, Early Chapter Books, Middle Grade Fiction, Poetry, Folk and Fairytales, Graphic Novels, and Nonfiction. They print out hundreds of gorgeous lists with lush covers and great interior art from the winners. The list will now be in its 105th year, and for those of us unable to see the print version (*sniff*) you can get to see the next best thing: An interactive one.

Each year New York Public Library produces what I seriously consider to be the most beautiful Best Books list of them all. Encompassing 100 books in total, it breaks all children’s books written in different categories to the following: Picture Books, Early Chapter Books, Middle Grade Fiction, Poetry, Folk and Fairytales, Graphic Novels, and Nonfiction. They print out hundreds of gorgeous lists with lush covers and great interior art from the winners. The list will now be in its 105th year, and for those of us unable to see the print version (*sniff*) you can get to see the next best thing: An interactive one.

Not to be outdone, the YA list of NYPL has arisen from the dead. You may not know it but the Books for the Teen Age list started decades and decades ago. It suffered quite a lot when it was renamed “Stuff for the Teen Age” (cause . . . teens don’t . . . read?) and then was killed outright in the bad old days when NYPL did away with specialties. Now things are happy and good again,  so after a trial run last year it’s almost up to full power. You can see their beauty of a list here.

so after a trial run last year it’s almost up to full power. You can see their beauty of a list here.

I was able to give my input to the children’s NYPL list up until my leaving at the end of July. The YA list pretty much operated outside my sphere. And I adore these choices. Do I agree with all of them? Not even! Example: No Cuckoo Song on the YA list, and in what universe is Human Body Theater doing there for teens?!?! I mean, seriously, that’s my 4-year-old’s favorite book. In any case, they’re still brilliant choices and the lists I spend all year waiting for. Huzzah!

I’m continuing our Teaching Authors series on good books we’ve been reading. Esther began with her list and highlighted one that carried her heart in its heart. (How I love that description!) April continued with her poetry favorite of the year—one of mine, too! Mary Ann listed three memorable YA novels. I’ve added them all to my long To Be Read list.

Like Mary Ann, I read a lot. Unfortunately, I don’t remember much, so when I find a book I really enjoy, I read it again. And maybe again after that. Here are a few of my recent reads that deserve a second or third look. I’m including brief excerpts to give you a taste of their tone and style.

Lizard Radio

Lizard Radio by Pat Schmatz. I love the inventive yet understandable language. This book made me think about gender identity and how complicated our society makes it.

“I have ten ticks to clean up and get to the Mealio. I drop the komodo in my pocket with the acorn, strap on my frods, and take off at a run. Pounding the earth, sucking in air, fire in my heart and blood rivers rushing through my body. There’s nothing in the world that feels as good as Lizard Radio in the great non-imaginary outdoors.”

Coincidentally, several of my recent reads have strong fairy tale themes.

Mechanica by Betsy Cornwell. After her father dies, a girl becomes a servant to her stepmother and stepsisters in her own home. She finds her mother’s hidden workshop and learns how to build magical mechanical creatures.

Mechanica by Betsy Cornwell. After her father dies, a girl becomes a servant to her stepmother and stepsisters in her own home. She finds her mother’s hidden workshop and learns how to build magical mechanical creatures.

“Most wonderful of all, I found other survivors from Mother’s insect-making days, the buzzers I’d so loved as a child, hidden in little boxes between her books or forgotten at the backs of drawers. By my fourth day in the workshop I had discovered two fat, gold-plated beetles; a week later, a many-jointed caterpillar that made loud ratcheting noises as it crawled across my desk joined their ranks. Within a month, I had found three spiders with needles for legs and steel spinnerets loaded with real thread; a large copper butterfly, so light and delicate that even with a metal wingspan the size of my two hands, it could glide and flutter about the room; and a little fleet of five dragonflies, their wings set with colored glass.”

Ash & Bramble by Sarah Prineas. Pin is a Seamstress, playing a role in a Story controlled by the powerful Godmother. Pin and Shoe, a Shoemaker, decide to break out of its confines.

Ash & Bramble by Sarah Prineas. Pin is a Seamstress, playing a role in a Story controlled by the powerful Godmother. Pin and Shoe, a Shoemaker, decide to break out of its confines.

“Coming around a bend, we see the waterfall slamming into the river with the city high on the cliff beyond. The sun is setting, and the waterfall looks like a veil of lace, and the white stone of the castle in the distance is tinged pink and gilded at its edges.

“Then the sun drops out of the sky and the hollow boom of the castle clock rolls out—it is the sound of a gravedigger knocking on a tomb door.”

Dark Shimmer by Donna Jo Napoli. I haven’t even finished this one yet, but I’m awed by the eerie perspective with which it begins. It turns into a huge surprise that I won’t reveal here.

Dark Shimmer by Donna Jo Napoli. I haven’t even finished this one yet, but I’m awed by the eerie perspective with which it begins. It turns into a huge surprise that I won’t reveal here.

“My knee split open in the fall. But I’m all right. I pick pebbles from the gash. I’m all right, I’m all right.“The boys creep up on bowed legs white as sticks without the bark, especially Tonso’s skinny leg, the one that never grew right. They peer in all directions.“I stand up. I’m older than these boys, but not by much. Still, they’re half my size.”

Eager to look ahead, I started gathering all the best books lists I could find. Because I think the world needs more awareness, I added a few lists that celebrate diversity. Then I found Publisher’s Weekly’s comprehensive “A Roundup of 2015’s Best Book Lists for Kids and Teens,” a good place to start. Here are links to more lists. - Chicago Public Library’s Kids’ Lists (“Best Informational Books for Older Readers,” “Best Fiction for Older Readers,” “Best Informational Books for Younger Readers,” “Best Fiction for Younger Readers,” and “Best Picture Books of 2015”)

- Toronto Public Library’s “First & Best 2015” (best Canadian books to help kids get ready for reading)

I can’t wait to dig in! Happy reading!

I can’t wait to dig in! Happy reading!

JoAnn Early Macken

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/8/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books,

Feiwel and Friends,

macmillan,

early chapter books,

funny early chapter books,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 early chapter books,

Sarah Courtauld,

Reviews,

Add a tag

Buckle and Squash: The Perilous Princess Plot

Buckle and Squash: The Perilous Princess Plot

By Sarah Courtauld

Feiwel and Friends (an imprint of Macmillan)

$14.99

ISBN: 978-1-250-05277-3

Ages 7-10

On shelves now.

Considering that I will never but EVER write an early chapter book or, for that matter, an easy book for new readers, it’s funny how often I sit around contemplating their difficulty. More precisely, I want to know which ones are more difficult to write. Easy books sounds like they’d be the hardest, particularly since it is remarkably hard to siphon a book down to its most essential parts while also making it interesting. Then again, those early chapter books are the devil. We see whole bunches of them published every year but how many are the type you’d like to read to your kids at bedtime over and over and over again? Nothing against Magic Treehouse, but would it kill Mary Pope Osborne to include just one tiny giant name Bonnet? Or have her characters fake The Black Death with the aid of turnip soup? I guess that’s what’s so great about Sarah Courtauld’s early chapter book import The Perilous Princess Plot. Not only is it sublime bedtime reading, it’s also perfect for transitioning kids to longer books, AND it’s knock your socks off funny. Goat and gruel, there’s something for everyone here. Unless you hate humor. Then you’re out of luck.

Meet Lavender. Interests include princesses, being a princess someday, handsome princes, and princesses (did I mention that one?). Meet her younger sister, Eliza. Interests include not hearing Lavender mention anything fairy tale related ever ever again (to say nothing of her singing). The two live in the Middle of Nowhere, in the Forgotten Corner of the Kingdom, in the realm of Squerb and their lives are pretty ordinary. Ordinary, that is, until Lavender gets herself kidnapped by the villain Mordmont who is hoping to ransom a pricey princess. Now it’s up to Eliza and her trusty steed/goat Gertrude to rescue Lavender (whether she wants to be rescued or not) and to generally save the day. There just might be a couple odd pit stops to attend to first.

It’s interesting. An author has a lot of ways of making a protagonist sympathetic to the her readership. Often in children’s books an instantaneous way is to make them the recipient of unfair treatment. Nothing captures hearts and minds more swiftly or efficiently than good old-fashioned outrage on behalf of your heroine and that’s certainly how Courtauld begins the book, with Eliza mucking out the goat pen as Lavender tra la las about. However, the real way in which you bond with Eliza is through your mutual annoyance with Lavender. Lavender is sort of what would happen if Fancy Nancy ever got so swallowed up in a princess obsession that she became unrecognizable to her family. Courtauld was quite clever to make Lavender the older sibling too. We’ve all seen the younger-princess-obsessed sibling motif in various books and while I’ve nothing against it, there’s something particularly grating when someone who, by dearth of age alone, should know better yet doesn’t.

In a given day you probably won’t read many early chapter books for kids that feel like the cast of Monty Python meandered out of retirement to write a book for children. Funny? Baby, you don’t know the half of it. Funny is hard. Funny is difficult. Funny is almost impossible to pin down because everyone’s sense of humor is different in some way from everyone else’s. But I simply refuse to believe that there’s a kid out there who could read this book and not crack a smile once. Here, I’ll give you an example. Early in the story the evil villain Mordmont is depressed. As he says, “I’m a man of simple pleasures . . . All I ever wanted was a castle, my own pride of lions, a jeweled crown, a choir of elves singing me awake each morning, sainthood, the power to make gold, the best mustache in Europe, a Jacuzzi, an elephant from the Indies, another one to be its friend, a singing giraffe, the power of invisibility, Magic Cheese Powers, a tiger with the feet of a lamb, the head of a lamb, and the body of a lamb – basically, a lamb – power over the sea, power over the letter C . . .” at which point we’re told that another 4,235 simple pleasures are to be skipped over so that we can fast forward to the final one, “a meringue that speaks Japanese.” It’s the lamb part that really got me. Love that lamb.

So let’s say you’re writing an early chapter book and you have the chance to illustrate it yourself. Do you do so? Particularly if it’s your debut novel? Yep. I’ve checked out her CV and from what I can tell Ms. Courtauld isn’t exactly a trained artist. In this respect she reminds me not a little of Abby Hanlon, another hilarious early chapter book author/self-taught illustrator whose Dory Fantasmagory is largely aided by her seemingly effortless pencilings. In this book too the art is deceptively simple. Just pencil sketches of silly tiny things, really. Yet I tell you right now that if some fancy pants illustrator walked up and said they’d redo the whole thing for free, I’d turn ‘em down flat. Courtauld has this perverse little style (in the best possible way, naturally) that just clicks with her storytelling. Some of it is obvious, like the view of a tearful rhino forced to watch Swan Lake, and some are visual gags so cheap that you just want to physically hug the book itself (like the image of people poking a girl after Mordmont talks about losing at poker). And how many early chapter book British imports can you name that contain images of Kanye West? I rest my case. Check and mate, babies.

According to a number of reputable sources this book has, “won the Sainsbury’s Book Award, and has been shortlisted for the Sheffield Children’s Book Prize and Coventry Inspiration Book Award.” In the U.K. it was also originally released with the title Buckle and Squash and the Monstrous Moat-Dragon. I’m not entirely certain why the U.S. publisher chose to change that one. Perilous plots are nice and all but they can’t really hold a candle to freakin’ moat dragons, now can they? I mean, it’s a dragon! In a moat! Still, a title change is a small price to pay when you get a book as good as this one. Hand it to a boy, hand it to a girl, hand it to a goat, they’ll all enjoy it in their own ways (though the goat may need a bit of a floss afterwards). If there are more Buckle and Squash books on the horizon, let us hope they float our way. I, for one, will look forward to those adventures. After all, the Monty Python guys can’t live forever. Time for someone else to pick up the torch.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews: Reading Rumpus

Professional Reviews:

Alternate Covers:

And here’s the book jacket whut wuz in Britain.

Misc: Read the first chapter here.

By:

Carmela Martino and 5 other authors,

on 12/7/2015

Blog:

Teaching Authors

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

young adult,

Nonfiction,

Mary Ann Rodman,

Conviction,

E.R. Frank,

M.T. Anderson,

Dime,

Kelly Loy Gilbert,

best books of 2015,

Symphony for the City of the Dead,

Add a tag

Santa isn't the only making his list and checking it twice. It's Award Season, when everyone and his dog make up "Best of the Year" book lists. This month, Teaching Authors takes a more casual approach; we're talking about the books that were memorable to us.

I read a lot. So how did I narrow down my "memorable" books? They are the ones I could remember the author, title, story and characters, without consulting my reading journal. My number one choice was a no brainer, since I put my life on hold until I finished the book. However, two others were a dead tie for second place. Surprise, surprise, all three are young adult. No grand plan on my part. They are the most outstanding books as far as I am concerned.

In a tie for second are:

Conviction by Kelly Loy Gilbert--What made this book memorable is that religion is part of the everyday lives of the characters without it being a book

about religion. Religion is not viewed in a cynical way, nor is it presented as the answer to life's questions. In fact, the characters

discover religion generates more questions than it "answers." A messy, complicated story that hops around from various points in the past, to the present, but somehow never loses the reader along the way.

Dime

Dime by E.R. Frank. Frank is known for her fearless approach to tough topics. She took on a big one this time; teen age prostitution.

Dime is a fourteen-year-old, lost in the foster care system. All she wants is a family and someone to love her. She finds it on the streets of Newark--a "daddy" to "take care of her," along with two other "wifeys" who work for Daddy. Dime will do anything Daddy tells her to because he "loves" her. Gradually, Dime sees the truth about her "family." The voices of Dime, Daddy and the wifeys are distinct, and non-stereotypical. To be honest, this book was heavy and intense that I wasn't sure I could finish, especially after I thought I where the story was heading. Dime herself, compelled me to finish. I'm glad I did.

So what kept me up nights, reading reading reading, even though, I knew how the story ended?" My first choice for personal reading is non-fiction, so it figures that one would be my "most memorable" of the year. My winner is a volume with the intimidating title of

Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad by M.T. Anderson. (Disclaimer: Although M.T. Anderson was one of my instructors in the Vermont College MFA program, we haven't been in touch in 15 years.)

I had misgivings. The book is 450+ pages (70 of which turned out to be documentation and indexes.) I already "knew" what happened: Shostakovich writes writes his Seventh Symphony, the "Leningrad" and the Nazis lose the Siege of Leningrad. Reading this book is truly not about the destination, but enjoying the ride. Even with such a potentially heavy subject, Anderson always finds a touch of humor in events. We see young Dmitri, a sheltered piano prodigy in Czarist Russia, evolve into a master composer within the confines of the Soviet system. We also see his career nose-dive when his work falls out of favor with The Party. What struck the deepest chord (sorry for the pun) in me was that while his physical world was in constant turmoil (messy love affairs, unemployment, starvation, Nazis...and a whole lot more) what gave his life meaning was music. He composed the "Leningrad" during the two and a half years the Nazis first tried to bomb, then starve, the city out of existence. Creativity triumphs all. Shostakovich's story (as well as the city of Leningrad's) has everything I love in a book...suspense, adventure, danger, intrigue, love, and most of all music. You don't have to know anything about Shostakovich, music or even Russia, to be sucked into this impeccably research story.

May 2016 be blessed with such terrific books as those of 2015!

Posted by Mary Ann Rodman

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/27/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

David Teague,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 picture books,

Reviews,

picture books,

Hyperion,

Best Books,

Antoinette Portis,

Disney Book Group,

Add a tag

The Red Hat

The Red Hat

By David Teague

Illustrated by Antoinette Portis

Disney Hyperion (an imprint of Disney Book Group)

$16.99

ISBN: 9781423134114

Ages 4-7

On shelves December 8th

There is a story out there, and I don’t know if it is true, that the great children’s librarian Anne Carroll Moore had such a low opinion of children’s books that involved “gimmicks” (read: interactive elements of any sort) that upon encountering them she’d dismiss each and every one with a single word: Truck. If it was seen as below contempt, it was “truck”. Pat the Bunny, for example, was not to her taste, but it did usher in a new era of children’s literature. Books that, to this day, utilize different tricks to engage the interest of child readers. In the best of cases the art and the text of a picture book are supposed to be of the highest possible caliber. To paraphrase Walter de la Mare, only the rarest kind of best is good enough for our kids, yes? That said, not all picture books have to attempt to be works of great, grand literature and artistic merit. There are funny books and silly ones that do just as well. Take it a step even farther, and I’d say that the interactive elements that so horrified Ms. Moore back in the day have great potential to aid in storytelling. Though she would be (rightly) disgusted by books like Rainbow Fish that entice children through methods cheap and deeply unappealing, I fancy The Red Hat would have given her pause. After considering the book seriously, a person can’t dismiss it merely because it tends towards the shiny. Lovingly written and elegantly drawn, Teague and Portis flirt with transparent spot gloss, but it’s their storytelling and artistic choices that will keep their young readers riveted.

With a name like Billy Hightower, it’s little wonder that the boy in question lives “atop the world’s tallest building”. It’s a beautiful view, but a lonely one, so when a construction crew one day builds a tower across the way, the appearance of a girl in a red hat intrigues Billy. Desperate to connect with her, he attempts various methods of communication, only to be stumped by the wind at every turn. Shouting fails. Paper airplanes plummet. A kite dances just out of reach. Then Billy tries the boldest method of reaching the girl possible, only to find that he himself is snatched from her grasp. Fortunately a soft landing and a good old-fashioned elevator trump the wind at last. Curlicues of spot gloss evoke the whirly-twirly wind and all its tricksy ways.

Great Moments of Spot Gloss in Picture Book History: Um . . . hm. That’s a stumper. I’m not saying it’s never happened. I’m just saying that when I myself try to conjure up a book, any book, that’s ever used it to proper effect, I pull up a blank. Now what do I mean exactly when I say this book is using this kind of “gloss”? Well, it’s a subtle layer of shininess. Not glittery, or anything so tawdry as that. From cover to interior spreads, these spirals of gloss evoke the invisible wind. They’re lovely but clearly mischievous, tossing messages and teasing the ties of a hat. Look at the book a couple times and you notice that the only part of the book that does not contain this shiny wind is the final two-page image of our heroes. They’re outdoors but the wind has been defeated in the face of Billy’s persistence. If you feel a peace looking at the two kids eyeing one another, it may have less to do with what you see than what you don’t.

Naturally Antoinette Portis is to be credited here, though I don’t know if the idea of using the spot gloss necessarily originated with her. It is possible that the book’s editor tossed Portis the manuscript with the clear understanding that gloss would be the name of the game. That said, I felt like the illustrator was given a great deal of room to grow with this book. I remember back in the day when her books Not a Box and Not a Stick were the height of 32-page minimalism. She has such a strong sense of design, but even when she was doing books like Wait and the rather gloriously titled Princess Super Kitty her color scheme was standard. In The Red Hat all you have to look at are great swath of blue, the black and white of the characters, an occasional jab of gray, and the moments when red makes an appearance. There is always a little jolt of red (around Billy’s neck, on a street light, from a carpet, etc). It’s the red coupled with that blue that really makes the book pop. By all rights a red, white, and blue cover should strike you on some level as patriotic. Not the case here.

Not that the book is without flaw. For the most part I enjoyed the pacing of the story. I loved the fairytale element of Billy tossed high into the sky by a jealous wind. I loved the color scheme, the gloss, and the characters. What I did not love was a moment near the end of the book where pertinent text is completely obscured by its placement on the art. Billy has flown and landed from the sky. He’s on the ground below, the wind buffeting him like made. He enters the girl’s building and takes the elevator up. The story says, “At the elevator, he punched UP, and he knocked at the first door on the top floor.” We see him extending his hand to the girl, her hat clutched in the other. Then you turn the page and it just says, “The Beginning.” Wait, what? I had to go back and really check before I realized that there was a whole slew of text and dialogue hidden at the bottom of that previous spread. Against a speckled gray and white floor the black text is expertly camouflaged. I know that some designers cringe at the thought of suddenly interjecting a white text box around a selection of writing, but in this particular case I’m afraid it was almost a necessity. Either than or toning down the speckles to the lightest of light grays.

Aside from that, it’s sublime. A sweet story of friendship (possibly leading to more someday) from the top of the world. Do we really believe that Billy lives on the top of the highest building in the world? Billy apparently does, and that’s good enough for us. But even the tallest building can find its match. And even the loneliest of kids can, through sheer pig-headed persistence, make their voices heard. A windy, shiny book without a hint of bluster.

On shelves December 8th.

Source: F&G sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/19/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

nonfiction,

nonfiction picture books,

Claire Saxby,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

Graham Byrne,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 nonfiction,

2015 nonfiction picture books,

Add a tag

Emu

Emu

By Claire Saxby

Illustrated by Graham Byrne

Candlewick Press

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-7636-7479-3

Ages 4-7

On shelves now.

Alas for poor emu. Forever relegated to be consider a second rate ostrich, it encompasses all of the awkwardness and none of the stereotypes. Does anyone ever talk about burying your head in the sand like an emu? They do not. Are schoolchildren routinely called upon to ooh and aah at the size of an emu’s egg? They aren’t. And when you watch Swiss Family Robinson, do you ever find yourself wishing that the kids would try to saddle an emu for the big race? Not even once. Emus are the second largest living bird in terms of height, coming right after the ostrich, and you might be fooled into believing that they are the less interesting of the two. There, you are wrong. Wrongdy wrongdy wrong wrong wrong. I do not wish to start a war of words with the prominent ostrich societies of the world, but after reading Emu by Claire Saxby (illustrated by Graham Byrne) I’m a bit of what you might consider an emu convert. Chock full of interesting information and facts about what a typical emu might experience in its day-to-day life, the book is full of thrills, chills, and a species that gives stay-at-home dads everywhere a true animal mascot.

Meet the emu. Do not be offended if he fails to rise when you approach. At the moment he is safeguarding a precious clutch of eggs from elements and predators. While many of us consider the job of hatching eggs to be something that falls to the female of the species, emus are different. Once they’ve laid their eggs, female emus just take off, and it is the male emu that hatches and rears them. In this particular example, the male emu has a brood of seven or so chicks but though they’re pretty big (ten times bigger than a domestic chicken hatchling) they need their dad for food, shelter, and protection. The chicks find their own food right from the start and within three to four months they’ve already lost their first feathers. They zigzag to escape predators, live with their fathers for about a year, and have a kick like you would not believe. Backmatter of the book provides more information about emus, as well as an index.

This is not what you might call Saxby and Byrne’s first rodeo show. The Aussie duo previously had paired together on the book Big Red Kangaroo, a book that did just fine for itself. Following a kangaroo called “Red”, the ostensibly nonfiction title was best described by PW as, “An understated but visually arresting portrait of a species.” For my part I had no real objections to the book, but neither did I have anything for it. Kangaroo books are not rare in my children’s rooms, though the book was different in that it was written for a younger reading level. That same reading level is the focus of Emu and here I feel that Saxby and Byrne have started to refine their technique. One of the problems I had with Red was this naming of the titular kangaroo. It felt false in a way. Like the author didn’t trust the readers enough to show them a typical day in the life of an animal without having to personalize it with faux monikers. Byrne’s art too felt flatter to me in that book than it does here. This may have more to do with the subject matter than anything else, though. Emu faces, after all, are inherently more amusing and interesting than kangaroos

This is not what you might call Saxby and Byrne’s first rodeo show. The Aussie duo previously had paired together on the book Big Red Kangaroo, a book that did just fine for itself. Following a kangaroo called “Red”, the ostensibly nonfiction title was best described by PW as, “An understated but visually arresting portrait of a species.” For my part I had no real objections to the book, but neither did I have anything for it. Kangaroo books are not rare in my children’s rooms, though the book was different in that it was written for a younger reading level. That same reading level is the focus of Emu and here I feel that Saxby and Byrne have started to refine their technique. One of the problems I had with Red was this naming of the titular kangaroo. It felt false in a way. Like the author didn’t trust the readers enough to show them a typical day in the life of an animal without having to personalize it with faux monikers. Byrne’s art too felt flatter to me in that book than it does here. This may have more to do with the subject matter than anything else, though. Emu faces, after all, are inherently more amusing and interesting than kangaroos

In terms of the text, Saxby utilizes a technique that’s proven very popular with teachers as of late. When kids in classrooms are given open reading time there can sometimes be a real range in reading levels. With this in mind, sometimes nonfiction picture books about the natural world will contain two types of text. There will be the more enticing narrative, ideal for reading aloud to a group or one-on-one. Then, for those budding naturalists, there will be a complementary second section that contains the facts. On the first two pages of Emu, for example, one side introduces the open forest with its “honey-pale sunshine” and the emu’s job while the second block of text, written in a small font that brings to mind an expert’s crisp clean handwriting, gives the statistics about emu (whether or not they can fly, their weight, height, etc.). In the back of the book under the Index there’s actually a little note about these sections. It says, “Don’t forget to look at both kinds of words”, and then writes the words “this kind and this kind” in the two different fonts.

Artist Graham Byrne’s bio says that he’s an electrical engineer, builder, and artist. This is his second picture book and the art is rendered digitally. What it looks like is scratchboard art, with maybe an ink overlay as well. I enjoyed the sense of place and the landscapes but what really made me happy was how Byrne draws an emu. There’s something about that bright yellow eye in the otherwise impassive face that gets me. I say impassive, but there are times when one wonders if Byrne is fighting an instinct to give his emu some expression. There’s a scene of the emu nosing his eggs, his beak appears to be curling up in just the slightest of smiles. Later an eagle threatens his brood and there’s almost a hint of a frown as he runs over to the rescue. It’s not enough to take you out of the story, but such images bear watching.

Artist Graham Byrne’s bio says that he’s an electrical engineer, builder, and artist. This is his second picture book and the art is rendered digitally. What it looks like is scratchboard art, with maybe an ink overlay as well. I enjoyed the sense of place and the landscapes but what really made me happy was how Byrne draws an emu. There’s something about that bright yellow eye in the otherwise impassive face that gets me. I say impassive, but there are times when one wonders if Byrne is fighting an instinct to give his emu some expression. There’s a scene of the emu nosing his eggs, his beak appears to be curling up in just the slightest of smiles. Later an eagle threatens his brood and there’s almost a hint of a frown as he runs over to the rescue. It’s not enough to take you out of the story, but such images bear watching.

In comparing the emu to the ostrich I may have omitted certain pertinent details. After all, the emu doesn’t have it quite so bad. It appears on the Australian coat of arms, as well as on their money. There was an Emu War of 1932 where the emus actually won the day. Heck, it’s even not too difficult to find emus on farms in the United States. Still, culturally they’ve a far ways to go if ever they are to catch up with their ostrichy brethren fame-wise. Books like this one will help. I think there must be plenty of teachers out there a little tired of using Eric Carle’s Mister Seahorse as their de facto responsible-dads-in-the-wild motif. Now kids outside of Australia will get a glimpse of this wild, wacky, wonderful and weird creature. Consider it worth meeting.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/2/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade fiction,

historical fiction,

middle grade historical fiction,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 historical fiction,

2015 middle grade novels,

Reviews,

Best Books,

Add a tag

Gone Crazy in Alabama

Gone Crazy in Alabama

By Rita Williams-Garcia

Amistad (an imprint of Harper Collins)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0062215871

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

I’m a conceited enough children’s librarian that I like it when a book wins me over. I don’t want them to make it easy for me. When I sit down to read something I want to know that the author on the other side of the manuscript is scrabbling to get the reader’s attention. Granted that reader is supposed to be a 10-year-old kid and not a 37-year-old woman, but to a certain extent audience is audience. Now I’ll say right off the bat that under normal circumstances I don’t tend to read sequels and I CERTAINLY don’t review them. There are too many books published in a current year to keep circling back to the same authors over and over again. There are, however, always exceptions to the rule. And who amongst us can say that Rita Williams-Garcia is anything but exceptional? The Gaither Sisters chronicles (you could also call them the One Crazy Summer Books and I think you’d be in the clear) have fast become modern day literary classics for kids. Funny, painful, chock full of a veritable cornucopia of historical incidents, and best of all they stick in your brain like honey to biscuits. Read one of these books and you can recall them for years at a time. Now the bitter sweetness of “Gone Crazy in Alabama” gives us more of what we want (Vonetta! Uncle Darnell! Big Ma!) in a final, epic, bow.

Going to visit relatives can be a chore. Going to visit warring relatives? Now THAT is fun! Sisters Delphine, Vonetta, and Fern have been to Oakland and Brooklyn but now they’ve turned South to Alabama to visit their grandmother Big Ma, their great-grandmother Ma Charles, and Ma Charles’s half sister Miss Trotter. Delphine, as usual, places herself in charge of her younger, rebellious, sisters, not that they ever appreciate it. As she learns more about her family’s history (and the reason the two half sisters loathe one another) she ignores her own immediate family’s needs until the moment when it almost becomes too late.

I’m an oldest sister. I have two younger siblings. Unlike Delphine I didn’t have the responsibility of watching over my siblings for any extended amount of time. As a result, I didn’t pay all that much attention to them growing up. But like Delphine, I would occasionally find myself trying, to my mind anyway, to keep them in line. Where Rita Williams-Garcia excels above all her peers, and I do mean all of them, is in the exchanges between these three girls. If I had an infinite revenue stream I would solicit someone to adapt their conversations into a very short play for kids to perform somewhere (actually, I’d just like to see ALL these books as plays for children, but that’s neither here nor there). The dialogue sucks you in and you find yourself getting emotionally involved. Because Delphine is our narrator you’re getting everything from her perspective and in this the author really makes you feel like she’s on the right side of every argument. It would be an excellent writing exercise to charge a class of sixth graders with the task of rewriting one of these sections from Vonetta or Fern’s point of view instead.

As I might have mentioned before, I wasn’t actually sold initially on this book. Truth be told, I liked the sequel to One Crazy Summer (called P.S. Be Eleven) but found the ending rushed and a tad unsatisfying. That’s just me, and my hopes with Gone Crazy were not initially helped by this book’s beginning. I liked the set-up of going South and all that, but once they arrived in Alabama I was almost immediately confused. We met Ma Charles and then very soon thereafter we met another woman very much like her who lived on the other side of a creek. No explanation was forthcoming about these two, save some cryptic descriptions of wedding photos, and I felt very much out to sea. My instinct is to say that a child reader would feel the same way, but kids have a way of taking confusing material at face value, so I suspect the confusion was of the adult variety more than anything else. Clearly Ms. Williams-Garcia was setting all this up for the big reveal of the half-sister’s relationship, and I appreciated that, but at the same time I thought it could have been introduced in a different way. Things were tepid for me for a while, but then the story really started picking up. By the time we got to the storm, I was sold.

And it was at this point in the book that I realized that I’d been coming at the book all wrong. Williams-Garcia was feeding me red herrings and I’m gulping them down like there’s no tomorrow. This book isn’t laser focusing its attention on great big epic themes of historical consequence. All this book is, all it ever has been, all the entire SERIES is about in its heart of hearts, is family. And that’s it. The central tension can be boiled down to something as simple and effective as whether or not Delphine and Vonetta can be friends. Folks are always talking about bullying and bully books. They tend to involve schoolmates, not siblings, but as Gone Crazy in Alabama shows, sometimes bullying is a lot closer to home than anyone (including the bully) is willing to acknowledge.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about needing more diverse books for kids, and it’s absolutely a valid concern. I have always been of the opinion, however, that we also need a lot more funny diverse books. When most reading lists’ sole hat tip to the African-American experience is Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (no offense to Mildred D. Taylor, but you see what I’m getting at here) while the white kids star in books like Harriet the Spy and Frindle, something’s gotta change. We Need Diverse Books? We Need FUNNY Diverse Books too. Something someone’s going to enjoy reading and want to pick up again. That’s why Christopher Paul Curtis has been such a genius the last few years (because, seriously, who else would explore the ramifications of vomiting on Frederick Douglass?) and why the name Rita Williams-Garcia will be remembered long after you and I are tasty toasty worm food. Because this book IS funny while also balancing out pain and hurt and hope.

An interviewer once asked Ms. Williams-Garcia if she ever had younger sisters like the ones in this book or if she’d ever spent a lot of time in rural Alabama, like they do here. She replied good-naturedly that nope. It reminded me of that story they tell about Dustin Hoffman playing Richard III. He put stones in his shoes to get the limp right. Laurence Olivier caught wind of this and his response was along the lines of, “My dear boy, why don’t you try acting?” That’s Ms. Williams-Garcia for you. She does honest-to-goodness writing. Writing that can conjure up estranged siblings and acts of nature. Writing that will make you laugh and think and think again after that. Beautifully done, every last page. A trilogy winds down on just the right note.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/19/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

graphic novels,

First Second,

Roaring Brook,

Best Books,

macmillan,

middle grade graphic novels,

nonfiction graphic novels,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 graphic novels,

funny graphic novels,

Maris Wicks,

Add a tag

Human Body Theater

Human Body Theater

By Maris Wicks

First Second (a imprint of Roaring Brook and division of Macmillan)

$14.99

ISBN: 978-1-59643-929-0

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

I gotta come clean with you. Skeletons? I’ve got a thing for them. Not a “thing” as in I find them attractive, but rather a “thing” as in I find them fascinating. I always have. Back in the 80s there was a science-related Canadian television show called “Owl TV” (a Canuck alternative to “3-2-1 Contact”) and one of the regular features was a skeleton by the name of Bonaparte who taught kids about various scientific matters. But aside from the odd viewing of “Jason and the Argonauts”, walking, talking (or, at the very least, stalking) skeletons don’t crop up all that often when you become grown. So maybe my attachment to Human Body Theater with its knobby narrator has its roots deep in my own personal history. Or maybe it has something more to do with the witty writing, untold gobs of nonfiction information, eye-catching art, and general sense of intelligence and care. Whatever the case, it turns out the human body puts on one heckuva good show!

When a human skeleton comes out and offers to right there, before your very eyes, become a fully formed human being with guts, skin, etc. who are you to refuse? Tonight the human body itself is putting on a show and everyone from the stagehands (the cells) to the players (whether they’re body parts or viruses) is fully engaged and involved. With our narrator’s help we dive deep beneath the skin and learn top to bottom about every possible system our bods have to offer. When all is said and done the readers aren’t just intrigued. They’re picking the book up to read it again and again. Backmatter includes a Glossary of terms and a Bibliography for further reading.

I’ve been a big time Maris Wicks fan for years. It started long ago when I was tooling around a MOCCA (Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art) event and ran across just the cutest little paperback picture book. It couldn’t have been much bigger than a coaster and all it was was a story about a family taking a daytrip to the woods. Called Yes, Let’s it was written by Galen Goodwin and illustrated by a Maris Wicks. I didn’t know either of these people. I just knew the book was good, and when it was published officially a couple years later by Tanglewood Publishing I felt quite justified. But for all that I’d been a fan, I didn’t recognize Ms. Wicks’ work or name, at first, when she illustrated Jim Ottaviani’s Primates. When the connection was made I felt like I’d won a small lottery. Now she’s gone solo with Human Body Theater and the only question left in anybody’s mind is . . . why didn’t she do it sooner? She’s a natural!

I’ve been a big time Maris Wicks fan for years. It started long ago when I was tooling around a MOCCA (Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art) event and ran across just the cutest little paperback picture book. It couldn’t have been much bigger than a coaster and all it was was a story about a family taking a daytrip to the woods. Called Yes, Let’s it was written by Galen Goodwin and illustrated by a Maris Wicks. I didn’t know either of these people. I just knew the book was good, and when it was published officially a couple years later by Tanglewood Publishing I felt quite justified. But for all that I’d been a fan, I didn’t recognize Ms. Wicks’ work or name, at first, when she illustrated Jim Ottaviani’s Primates. When the connection was made I felt like I’d won a small lottery. Now she’s gone solo with Human Body Theater and the only question left in anybody’s mind is . . . why didn’t she do it sooner? She’s a natural!

Now for whatever reason my four-year-old is currently entranced by this book. She’s naturally inclined to love graphic novels anyway (thank you, Cece Bell) and something in Human Body Theater struck a real chord with her. It’s not hard to figure out why. Visually it’s consistently arresting. Potentially dry material, like the method by which oxygen travels from the lungs to the blood, is presented in the most eclectic way possible (in this case, like a dance). Wicks keeps her panels vibrant and consistently interesting. One minute we might be peering into the inner workings of the capillaries and the next we’re zooming with the blood through the body delivering nutrients and oxygen. The colorful, clear lined style certainly bears a passing similarity to the work of author/artists like Raina Telgemeier, while the ability imbue everything, right down to the smallest atom, with personality is more along the lines of Dan Green’s “Basher Books” series.

For my part, I was impressed with the degree to which Wicks is capable of breaking complex ideas down into simple presentations. The chapters divide neatly into The Skeletal System, The Muscular System, The Respiratory System, The Cardiovascular System, The Digestive System, The Excretory System, The Endocrine System, The Reproductive System, The Immune System, The Nervous System, and the senses (not to mention an early section on cells, elements, and molecules). As impressive as her art is, it’s Wicks’ writing that I feel like we should really credit here. Consider the amount of judicious editing she had to do, to figure out what to keep and what to cut. How do you, as an author, transition neatly from talking about reproduction to the immune system? How do you even tackle a subject as vast as the senses? And most importantly, how gross do you get? Because the funny bones of 10-year-olds demand a certain level of gross out humor, while the stomachs of the gatekeepers buying the book demand that it not go too far. I am happy to report that Ms. Wicks walks that tightrope with infinite skill.

One of the parts of the book I was particularly curious about was the sex and reproduction section. I’ve seen what Robie H. Harris has gone through with her It’s Perfectly Normal series on changing adolescent bodies, and I wondered to what extent Wicks would tread similar ground. The answer? She doesn’t really. Sex is addressed but images of breasts and penises are kept simple to the point of near abstraction. As such, don’t be relying on this for your kid’s sex-ed. There are clear reasons for this limitation, of course. Books that show these body parts, particularly graphic novels, are restricted by some parents or school districts. Wicks even plays with this fact, displaying a sheet covering what looks like a possible penis, only to reveal a very tall sperm instead. And Wicks doesn’t skimp on the info. The chapter on The Reproductive Cycle, for example, contains the delightful phrase, “ATTENTION: Would some blood please report to the penis for a routine erection.” So I’ve no doubt that there will be a parent somewhere who is offended in some way. However, it’s done so succinctly that I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if it causes almost no offense during its publication lifespan (but don’t quote me on that one).