new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: middle school novels, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: middle school novels in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/21/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fantasy,

funny books,

Best Books,

abrams,

Amulet Books,

Amy Ignatow,

middle school novels,

middle school fantasy,

funny fantasy,

Best Books of 2016,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fantasy,

2016 middle grade fiction,

2016 funny books,

2016 middle school fiction,

Add a tag

The Mighty Odds

The Mighty Odds

By Amy Ignatow

Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams)

$15.95

ISBN: 978-1-4197-1271-5

Ages 10 and up

On shelves September 13th

If you could have one weird superpower, what would it be? Not a normal one, mind you. We’re not doing a flight vs. invisibility discussion here. The power would have to be extraordinary and odd. If it’s completely useless, all the better. Me? I think I’d like my voice to be same as the voice you hear in your head when you’re reading something. You know that voice? That would be my superpower. A good author can crank this concept up to eleven if they want to. Enter, Amy Ignatow. She is one of the rare authors capable of making me laugh out loud at the back covers of her books. For years she’s penned The Popularity Papers to great success and acclaim. Now that very realistic school focus is getting a bit of a sci-fi/fantasy kick in the pants. In The Mighty Odds, Ignatow takes the old misfits-join-together-to-save-the-world concept and throws in a lot of complex discussions of race, middle school politics, bullying, and good old-fashioned invisible men. The end result is a 21st century superhero story for kids that’s keeps you guessing every step of the way.

A school bus crashes in a field. No! Don’t worry! No one is killed (that we can tell). And the bus was just full of a bunch of disparate kids without any particular connection to one another. There was the substitute teacher and the bus driver (who has disappeared). And there was mean girl Cookie (the only black girl in school and one of the most popular), Farshad (nicknamed “Terror Boy” long ago by Cookie), Nick (nerdy and sweet), and Martina (the girl no one notices, though she’s always drawing in her sketchbook). After the accident everything should have just gotten back to normal. Trouble is, it didn’t. Each person who was on or near the bus when the accident occurred is a little bit different. It might be a small thing, like the fact that Martina’s eyes keep changing color. It might be a weird thing, like how Cookie can read people’s minds when they’re thinking of directions. It might be a powerful thing, like Farad’s super strength in his thumbs. Or it might be a potentially powerful, currently weird thing like Nick’s sudden ability to teleport four inches to his left. And that’s before they discover that someone is after them. Someone who means them harm.

Superhero misfits are necessarily new. Remember Mystery Men? This book reminded me a lot of that old comic book series / feature film. In both cases superpowers are less a metaphor and more a vehicle for hilarity. I read a lot of books for kids but only once in a while do I find one enjoyable enough to sneak additional reads of on the sly. This book hooked me fairly early on, and I credit its sense of humor for that. Here’s a good example of it. Early in the book Cookie and a friend are caught leaving the field trip for their own little side adventure. The kids in their class speculate what they got up to and one says that clearly they got drunk. Farshad’s dry wit then says, “… because two twelve-year-olds finding a bar in Philadelphia that would serve them at eleven A.M. was completely plausible.” Add in the fact that they go to “Deborah Read Middle School” (you’ll have to look it up) and I’m good to go.

Like I’ve said, the book could have just been another fun, bloodless superhero misfit storyline. But Ignatow likes challenges. When she wrote the Popularity Papers books she gave one of her two heroines two dads and then filled the pages with cursive handwriting. Here, her heroes are a variety of different races and backgrounds, but this isn’t a Benetton ad. People don’t get along. Cookie’s the only black kid in her school and she’s been very careful to cement herself as popular from the start. When her mom moved them to Muellersville, Cookie had to be careful to find a way to become “the most popular and powerful person in school.” Martina suggests at one point that she likes being angry, and indeed when the world starts to go crazy on her the thing that grounds her, if only for a moment, is anger. And why shouldn’t she be angry? Her mom moved her away from her extended family to a town where she knew no one, and then her mother married a guy with two kids fairly fast. Cookie herself speculates about the fact that she probably has more in common with Farshad than she’d admit. “He was the Arab Kid, just like Cookie was the Black Girl and Harshita Singh was the Indian Girl and Danny Valdez was the Hispanic Guy and Emma Lee was the Asian Chick. They should have all formed a posse long ago and walked around Muellersville together, just to freak people out.” Cookie realizes that she and Farshad need to have one another’s backs. “It was one thing to be a brown person in Muellersville and another to be a brown person in Muellersville with superpowers.” At this point in time Ignatow doesn’t dig any deeper into this, but Cookie’s history, intentions, and growth give her a depth you won’t find in the usual popular girl narrative.

For the record, I have a real appreciation for contemporary books that feature characters that get almost zero representation in books. For example, one of the many things I love about Tom Angleberger’s The Qwikpick Papers series is that one of the three heroes is Jehovah’s Witness. In this book, one of the kids that comes to join our heroes is Amish. Amish kids are out there. They exist. And they almost never EVER get heroic roles in stories about a group of friends. And Abe doesn’t have a large role in this book, it’s true, but it’s coming.

Having just one African-American in the school means that you’re going to have ignorant other characters. Cookie has done a good job at getting the popular kids in line, but that doesn’t mean that everyone is suddenly enlightened. Anyone can be tone deaf. Even one of our heroes, which in this case means Nick’s best friend, the somewhat ADD, always chipper Jay. Now I’ve an odd bit of affection for Jay, and not just because in his endless optimism he honestly thinks he’ll get permission to show his class Evil Dead Two on the field trip bus (this may also mark the first time an Evil Dead film has been name dropped in a middle grade novel, by the way). The trouble comes when he talks about Cookie. He has a tendency to not just be tone deaf but veering into really racially questionable territory when he praises her. Imagine a somewhat racist Pepe Le Pew. That’s Jay. He’s a small town kid who’s only known a single solitary black person his entire life and he’s enamored with her. Still, that’s no excuse for calling her “my gorgeous Nubian queen” or saying someday they’ll “make coffee-colored babies.” I expected a little more a comeuppance for Jay and his comments, but I suppose that’ll have to wait for a future book in the series. At the very least, his words are sure to raise more than few eyebrows from readers.

Funny is good. Great even. But funny doesn’t lift a middle grade book out of the morass of other middle grade books that are clogging up the bookstores and libraries of the world. To hit home you need to work just a smidgen of heart in there. A dose of reality. Farad’s plight as the victim of anti-Muslim sentiment is very real, but it’s also Nick’s experiences with his dying/dead father that do some heavy lifting. As you get to know Nick, Ignatow sprinkles hints about his life throughout the text in a seamless manner. Like when Nick is thinking about weird days in his life and flashes back to the day after his dad’s funeral. He and his mom had “spent the entire day flopped on the couch, watching an impromptu movie marathon of random films (The Lord of the Rings, They Live, Some Like It Hot, Ghostbusters, and Babe) and eating fancy stuff from the gift baskets that people had sent, before finally getting up to order pizza.” There’s a strong smack of reality in that bit, and there are more like it in the book. A funny book that sucker punches your heart from time to time makes for good reading.

Lest we forget, this is an illustrated novel. Ignatow makes the somewhat gutsy choice of not explaining the art for a long time. Long before we even get to know Martina, we see her in various panels and spreads as an alien. In time, we learn that the art in this book is all her art, and that she draws herself as a Martian because that’s what her sister calls her. Not that you’ll know any of this for about 125 pages. The author makes you work to get at that little nugget of knowledge. By the way, as a character, Martina the artist is fascinating. She’s sort of the Luna Lovegood of the story. Or, as Nick puts it, “She had a sort of almost absentminded way of saying things that shouldn’t have been true but probably were.” There is one tiny flub in the art when Martina draws all the kids as superheroes and highlights Farshad’s thumbs, though at that point in the storyline Martina wouldn’t know that those are his secret weapons. Other than that, it’s pretty perfect.

Lest we forget, this is an illustrated novel. Ignatow makes the somewhat gutsy choice of not explaining the art for a long time. Long before we even get to know Martina, we see her in various panels and spreads as an alien. In time, we learn that the art in this book is all her art, and that she draws herself as a Martian because that’s what her sister calls her. Not that you’ll know any of this for about 125 pages. The author makes you work to get at that little nugget of knowledge. By the way, as a character, Martina the artist is fascinating. She’s sort of the Luna Lovegood of the story. Or, as Nick puts it, “She had a sort of almost absentminded way of saying things that shouldn’t have been true but probably were.” There is one tiny flub in the art when Martina draws all the kids as superheroes and highlights Farshad’s thumbs, though at that point in the storyline Martina wouldn’t know that those are his secret weapons. Other than that, it’s pretty perfect.

It’s also pretty clearly middle school fare, if based on language alone. You’ve got kids leaving messages on cinderblocks that read “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum” or “Don’t let the bastards get you down.” That may be the most realistic middle school detail I’ve read in a book in a long time. The bullying is systematic, realistic, and destructive (though that’s never clear to the people doing the bullying). A little more hard core than what an elementary school book might discuss. And Cookie is a superb bully. She’s honestly baffled when Farad confronts her about what she’s done to him with her rumors.

A word of warning to the wise: This is clearly the first book in a longer series. When you end this tale you will know the characters and know their powers but you still won’t know who the bad guys are exactly, why the kids got their powers (though the bus driver does drop one clue), or where the series is going next. For a story where not a lot of time passes, it really works the plotting and strong characterizations in there. I like middle grade books that dream big and shoot for the moon. “The Mighty Odds” does precisely that and also works in some other issues along the way. Just to show that it can. Great, fun, silly, fantastical fantasy work. A little smarter and a little weirder than most of the books out there today.

On shelves September 13th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Readalikes:

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 10/5/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Laura Amy Schlitz,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

middle school novels,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 historical fiction,

Add a tag

The Hired Girl

The Hired Girl

By Laura Amy Schlitz

Candlewick Press

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0763678180

Ages 12 and up

Bildungsroman. Definition: “A novel dealing with one person’s formative years or spiritual education.” A certain strain of English major quivers at the very term. Get enough Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man shoved down your gullet and you’d be quivering too. I don’t run across such books very often since I specialize primarily in books for children between the ages of 0-12. For them, the term doesn’t really apply. After all, books for kids are often about the formation of the self as it applies to other people. Harry finds his Hogwarts and Wilbur his spider. Books for teenagers are far better suited to the Bildungsroman format since they explore that transition from child to adult. Yet when you sit right down and think about it, the transition from childhood to teenagerhood is just as fraught. There is a beauty to that age, but it’s enormously hard to write. Only a few authors have ever attempted it and come out winners on the other side. Laura Amy Schlitz is one of the few. Writing a book that could only be written by her, published by the only publisher who would take a chance at it (Candlewick), Schlitz’s latest is pure pleasure on the page. A book for the child that comes up to you and says, “I’ve read Anne of Green Gables and Little Women. What’s new that’s like that?”

The last straw was the burning of her books. Probably. Even if Joan’s father hadn’t set her favorite stories to blazes, it’s possible that she would have run away eventually. What we do know is that after breaking her back working for a father who wouldn’t even let her attend school or speak to her old teacher, 14-year-old Joan Skraggs has had enough. She has the money her mother gave her before she died, hidden away, and a dream in mind. Perhaps if she runs away to Baltimore she might be able to find work as a hired girl. It wouldn’t be too different from what she’s done at home (and it could be considerably less filthy). Bad luck turns to good when Joan’s inability to find a boarding house lands her instead in the household of the Rosenbach family. They’re well-to-do Jewish members of the community and Joan has no experience with Jewish people. Nonetheless she is willing to learn, and learn she does! But when she takes her romantic nature a bit too far with the family, she’ll find her savior in the most unexpected of places.

I mentioned Anne of Green Gables in my opening paragraph, but I want to assure you that I don’t do so lightly. One does not bandy about Montgomery’s magnum opus. To explain precisely why I referenced it, however, I need to talk a little bit about a certain type of romantically inclined girl. She’s the kind that gets most of her knowledge of other people through books. She is by turns adorable and insufferable. Now, the insufferable part is easy to write. We are, by nature, inclined to dislike girls in their early teens that play a kind of mental dress-up that’s cute on kids and unnerving on adolescents. However, this character can be written and written well. Jo in Little Women comes through the age unscathed. Anne from Anne of Green Gables traipses awfully close to the awful side, but manages to charm the reader in the process (no mean feat). The “Girl” from the musical The Fantastiks would fit in this category as well. And finally, there is Joan in The Hired Girl. She vacillates wildly between successfully playing the part of a young woman and then going back to the younger side of adolescence. She pouts over not getting a kitten, for crying out loud. Adults reading this book will have a vastly different experience than kids and teens, then. To a grown-up (particularly a grown-up woman) Joan is almost painfully familiar. We remember the age of fourteen and what that felt like. That yearning for love and adventure. That yearning can be useful to you, but it can also make you bloody insufferable. As such, adults are going to be inclined to forgive Joan very easily. I can only hope that her personality allows younger readers to do the same.

My husband used to write and direct short historical films. They were labor intensive affairs where every car, house, and pot holder had to be accurate and of the period. It would have been vastly easier to just write and direct contemporary fare, but where’s the fun in that? I think of those days often when I read works of historical fiction. Labor intensive doesn’t even begin to explain what goes into an accurate look at history. Ms. Schlitz appears to be unaware of this, however, since not only has she written something set in the past, she throws the extra added difficulty of discussing religion into it as well. Working in a Jewish household at the turn of the century, Joan must come to grips with all kinds of concepts and ideas that she has hitherto been ignorant of. For this to work, the author tries something very tricky indeed. She makes certain that her heroine has grown up on a farm where her sole concept of Jewish people is from “Ivanhoe”, so that she is as innocent as a newborn babe. She isn’t refraining from anti-Semitism because she’s an apocryphal character. She’s just incapable of it due to her upbringing, and that’s a hard element to pull off. Had Ms. Schlitz pushed the early portion of this book any further, she would have possibly disinterested her potential readership right from the start. I have heard a reader say that the opening sequence with Joan’s family is too long, but I personally believe these sections where she wanders blindly in and out of various situations could not have worked if that section had been any shorter.

But as I say, historical fiction can be the devil to get right. Apocryphal elements have a way of seeping into the storyline. Your dialogue has to be believably from the time and yet not so stilted it turns off the reader. In this, Laura Amy Schlitz is master. This book feels very early 20th century. You wouldn’t blink an eye to learn it was fifty or one hundred years old (though its honest treatment of Jewish people is probably the giveaway that it’s contemporary). The language feels distinctive but it doesn’t push the young reader away. Indeed, you’re invited into Joan’s world right from the start. I also enjoyed very much her Catholicism. Characters that practice religion on a regular basis are so rare in contemporary books for kids these days.

As I mentioned, adults will read this book differently than the young readership for whom it is intended. I do think that if I were fourteen myself, this would be the kind of book I’d take to. By the same token, as an adult the theme that jumped out at me the most was that of motherhood. Joan’s mother died years before but she has a very palpable sense of her. Her memories are sharp and through her eyes we see the true tragedy of her mother’s life. How she wed a violent, hateful man because she felt she had no other choice. How she wasn’t cut out for the farm’s hard labor and essentially worked herself to death. How she saw her daughter’s future and found the means to save her (and by golly it works!). All the more reason to have your heart go out to Joan when she tries, time and again, to turn Mrs. Rosenbach into a substitute mother figure. It’s a role that Mrs. Rosenbach does NOT fit into in the least, but that doesn’t stop Joan from extended what is clearly teenaged rebellion onto a woman who isn’t her mother but her employer. Indeed, it’s Mrs. Rosenbach who later says, “I felt her wanting a mother.”

Is it a book for a certain kind of reader? Who am I to say? It’s a book I’d hand to a young me, so I don’t think I can necessarily judge who else would enjoy it. It’s beautiful and original and old and classic. It makes you feel good when you read it. It’s thick but it flies by. Because of the current state of publishing today books are either categorized as for children or for teens. The Hired Girl isn’t really for either. It’s for those kids poised between the two ages, desperate to be older but with bits of pieces of themselves stuck fast to their younger selves. A middle school novel of a time before there were middle schools. Beautifully written, wholly original, one-of-a-kind. Unlike anything you’ve read that’s been published in the last fifty years at least, and that is the highest kind of praise I can give.

On shelves now.

Professional Reviews:

Interviews: Laura speaks with SLJ about the book.

Videos:

More discussions of the book and where it came from!

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/19/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Random House,

Rebecca Stead,

realistic fiction,

Best Books,

middle school novels,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 middle school fiction,

2016 Newbery contender,

2015 realistic fiction,

Reviews,

Add a tag

Goodbye Stranger

Goodbye Stranger

By Rebecca Stead

Wendy Lamb Books (an imprint of Random House Children’s Books)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-385-74317-4

Ages 10-14

On shelves August 4th

After much consideration, I think I’m going to begin this review with what has to be the hoity toity-est opening I have ever come up with. Gird, thy loins, mes amies. In her 2006 book Betraying Spinoza: The Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity (don’t say you weren’t warned), philosopher Rebecca Goldstein wrote the following passage about the concept of personal identity: “What is it that makes a person the very person that she is, herself alone and not another, an integrity of identity that persists over time, undergoing changes and yet still continuing to be — until she does not continue any longer, at least not unproblematically?” In other words, why is the “you” that you were at five the same person as the “you” at thirteen or fourteen? Now I don’t know that a lot of 10-14 year olds spend their days contemplating the philosophical meanings behind their sense of self from one stage of life to another. But if they hadn’t before, they’re about to now. Goodbye Stranger by Rebecca Stead has taken what on the surface might look like a fluffy middle school tale of selfies and first loves and turned it into a much more layered discussion of bodies, feminism, the male (and female) gaze, female friendships, relationships, and betrayals. And fake moon landings. And fuzzy cat ear headbands. Hard to pin this one down, honestly.

By all logic, Bridge should have died when she was eight years old. She skated into the street and got hit by a car, after all. Yet Bridge lived and with seemingly no serious repercussions. Recently she’s been taking to wearing little black cat ears on her head, but her best friends Emily and Tab don’t mind. It’s their seventh grade year and there are bigger things on their minds. Emily’s been flirting with a cute older soccer player, Tab’s trying to save the world in her way, and now Bridge has become friends with Sherm, a guy she’d never even talked to until this year. When a wayward selfie throws the friends into a tizzy, it’s all the three can do to keep their promise to one another never to fight. Meanwhile, several months in the future, an unnamed teenager is skipping school. Something terrible has happened and she wants to avoid the blowback. But while thinking about her ex-best friend and the way things have changed, she may be unable to hide from herself as well as she hides from others.

Let’s get back to that idea that with every new age in your life, you’re an entirely different person than you were before. That philosopher I was quoting, Ms. Goldstein, asks, “Is death one of those adventures from which I can’t emerge as myself?” Actual death, she’s saying, is where you change into something other than your own “self” for good. But aren’t the changes throughout your life little deaths as well? Is that five-year-old you in that photograph really you? Do you share something essential? Stead isn’t delving deep into these questions but simply raising points to make kids think. So when her teenage character ponders that her best friend has undergone a change from which her old self will never return the book reads, “But another part of you, the part that stayed quiet, began to understand that maybe Vinny, your Vinny, was gone.” Poof! Sherm wonders something similar about his grandfather and the man’s odd actions. He writes in a letter that his grandfather now feels like a stranger and then says, “Is the new you the stranger? Or is the stranger the person you leave behind?”

To write one part of the book, the teenager, in the second person was a daring choice. It’s so unusual, in fact, that you cannot look at it without wondering what the reasoning was behind its direction. When Ms. Stead was deciding how to put Goodbye Stranger together, there had to come a point where she made the conscious decision that the teenager’s voice could only work in the second person. Why? Maybe to make the reader identify with her more directly. Maybe to make her tale, which is significantly less fraught than some of the other stories in this book, more immediate and in your face. Insofar as it goes, it works. The purpose of the narrative is perhaps to prove to kids that age does not necessarily begat wisdom. For them, the revelation of the identity of the runaway, who was previously seen as so wise and older, should prove a bit of a shocker. It also drives home the theme of changing personalities and who the “self” really is from one age to another really well.

Right now, I can predict the future. Don’t believe me? It’s true. I see hundreds of children’s books clubs assigned this book. I see hundreds of teachers having kids read it over the summer. And time after time I see kids handed sheets of paper (or maybe virtual paper – I’m flexible) with a bunch of questions about the book and their interpretation of the events. And right there, clear as crystal, is the following question: “What is the significance of Bridge’s cat ears?” Don’t answer that, kids. Don’t do it. Because if the adult who handed you this book is asking you that question, then they themselves didn’t really read the book. You could ask a hundred questions about “Goodbye Stranger” but if the cat ears are your focus then I think you took the wrong message away from this story.

And there’s such beautiful prose to be enjoyed as well. Sentences like “You can see the sun touching the tops of the buildings across the street, making its way through the neighborhood like someone whose attention you are careful not to attract.” Or, “You can have it all, but you can’t have it all at once.” And maybe my favorite one, “You know what my dad told me once? He said the human heart doesn’t really pump the way everyone thinks . . . He said that the heart wrings itself out. It twists in two different directions, like you’d do to squeeze the water out of a wet towel.” Trust me – if I could spend the rest of this review just quoting from this book, I’d do it. I suspect that would only amuse me in the end, though.

Bane of the cataloging librarian’s job, this book is a middle school title for middle schoolers. Not young kids. Not jaded teens. Middle. School. Kids. As such, were it not for the author’s fantastic writing and already existing fan base, it would languish away in that no man’s land between child and teen fiction. Fortunately Stead has a longstanding, strong, and dedicated group of young followers who are willing to dip a toe into the potentially murky world of middle school. There they will find exactly what we all found when we were that age. There will be kids who seem to be enjoying an extended childhood, while others have found themselves thrust into mature bodies they have no experience operating. With this book the selfie has officially entered the children’s literature lexicon and woe betide those who seek to turn back the clock. Naturally, this will lead some adults to believe that the book is better suited in the YA and teen sections of their libraries and bookstores. I condemn no one’s choice on where best to place this book, particularly since some communities are a bit more conservative in their tastes and attitudes than others. That said, I am of the firm opinion that this is a book for kids. We may like to believe that the situations that occur here (and they are very PG situations, for what it’s worth) don’t occur in the real world, but we’d be fooling ourselves. If the heroine of the book had been Bridge’s friend Emily and not Bridge herself, then a stronger case could be made for the book’s YA inclinations. Moreover the tone of the book, while certainly filled with intelligent kids, is truly intended for a child audience. Adults will enjoy it. Teens might even enjoy it. But it’s kids that will benefit the most from it in the end.

The trickiest part of the book, and the part that may raise the most eyebrows, is Stead’s handling of the notion of feminism and the perception of girls and women. Emily and Bridge’s friend Tab takes a class from a woman who seems to have stepped out of a 1974 women’s studies college course. Her name is Ms. Berman but she says the kids can call her Berperson. Tab, for her part, devours everything the Berperson (as they prefer to call her) says and then takes what she’s learned and applies it in a bad way. She’s a middle schooler. There are college girls who do very much the same thing. So I watched very closely to see how Tab’s feminist interpretation of events went down. First off, the Berperson does not approve of what Tab does later in the book. Then I wanted to see if Tab’s continual feminist statements made any good points. Sometimes they really really do. When it comes to the selfie, Tab’s the smartest of her three friends. Other times she’s incredibly annoying. So what’s a kid going to take away from this book re: feminism? For the most part, it’s complicated but the end result is that Tab is left, for all her smarts early on, a fool. That’s a strong message and one that I’m worried will cast a long shadow over the concept of feminism itself, reinforcing stereotypes that it’s humorless and self-righteous. On the flip side, there are some very intelligent things being said about how girls are perceived in society. When a girl is slut shamed (the exact phrase isn’t used but that’s what it is) for her picture, she says later, “But the bad part wasn’t that everyone was looking at the picture. I mean, it was weird and not great. But the bad part was that it felt like they were making fun of my feeling good about the picture. Of me liking myself.” Lots to unpack there.

If Stead has a known style then perhaps it’s in writing mysteries that aren’t mysteries. Every question raised by the text along with every loose end is tied up by the story’s close. Characters are smart and their interactions with one another carry the thrill of authenticity. Stead is sort of a twenty-first century E.L. Konigsburg. Her kids are intelligent but (unlike Konigsberg, I would argue) they still feel like kids. And there are connections between the characters and events that you didn’t even think to hope for until, at last, they are revealed to you. I heard one adult who had read this book say that it was “layered”. I suppose that’s a pretty good way of describing it. It has this surface simplicity to it but even the slightest scratch to that surface yields gold. I’ve focused on just a couple of the aspects of the title that I personally find interesting, but there are so many other directions that a person could go with it. If Stead has a known style, maybe it isn’t mysteries or kids smart beyond their years or multiple connections. Maybe her style is just writing great books. The evidence in this case speaks for itself.

On shelves August 4th

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews: educating alice

Videos:

Those of a certain generation may be unable to read the title of this book without the Supertramp song of the same name coming to mind. So, with them in mind . . .

Note the waitress. I wonder if she’s taking a vanilla shake and cinnamon toast to a table.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 1/13/2015

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

British imports,

middle grade historical fantasy,

middle school novels,

Best Books of 2015,

Reviews 2015,

2015 reviews,

2015 fantasy,

2015 middle school fiction,

middle school fantasy,

Reviews,

horror,

fantasy,

middle grade fantasy,

Best Books,

Frances Hardinge,

Add a tag

Cuckoo Song

Cuckoo Song

By Frances Hardinge

Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams)

$17.95

ISBN: 978-1419714801

Ages 10 and up

On shelves May 12, 2015

I was watching the third Hobbit movie the other day (bear with me – I’m going somewhere with this) with no particular pleasure. There are few things in life more painful to a children’s librarian than watching an enjoyable adventure for kids lengthened and turned into adult-centric fare, then sliced up into three sections. Still, it’s always interesting to see how filmmakers wish to adapt material and as I sat there, only moderately stultified, the so-called “Battle of the Five Armies” (which, in this film, could be renamed “The Battle of the Thirteen Odd Armies, Give Or Take a Few) comes to a head as the glorious eagles swoop in. “They’re the Americans”, my husband noted. It took a minute for this to register. “What?” “They’re the Americans. Tolkien wrote this book after WWI and the eagles are the Yanks that swoop in to save the day at the very last minute.” I sat there thinking about it. England has always had far closer ties to The Great War than America, it’s true. I remember sitting in school, baffled by the vague version I was fed. American children are taught primarily Revolutionary War, Civil War, and WWII fare. All other conflicts are of seemingly equal non-importance after those big three. Yet with the 100 year anniversary of the war to end all wars, the English, who had a much larger role to play, are, like Tolkien, still producing innovative, evocative, unbelievable takes that utilize fantasy to help us understand it. And few books do a better job of pinpointing the post traumatic stress syndrome of a post-WWI nation than Frances Hardinge’s Cuckoo Song. They will tell you that it’s a creepy doll book with changelings and fairies and things that go bump in the night. It is all of that. It is also one of the smartest dissections of what happens when a war is done and the survivors are left to put their lives back together. Some do a good job. Some do not.

Eleven-year-old Triss is not well. She knows this, but as with many illnesses she’s having a hard time pinpointing what exactly is wrong. It probably had to do with the fact that she was fished out of the Grimmer, a body of water near the old stone house where her family likes to vacation. Still, that doesn’t explain why her sister is suddenly acting angry and afraid of her. It doesn’t explain why she’s suddenly voracious, devouring plate after plate of food in a kind of half mad frenzy. And it doesn’t explain some of the odder things that have been happening lately either. The dolls that don’t just talk but scream too. The fact that she’s waking up with dead leaves in her hair and bed. And that’s all before her sister is nearly kidnapped by a movie screen, a tailor tries to burn her alive, and she discovers a world within her world where things are topsy turvy and she doesn’t even know who she is anymore. Triss isn’t the girl she once was. And time is running out.

From that description you’d be justified in wondering why I spent the better half of the opening paragraph of this review discussing WWI. After all, there is nothing particularly war-like in that summary. It would behoove me to me mention then that all this takes place a year or two after the war. Triss’s older brother died in the conflict, leaving his family to pick up the pieces. Like all parents, his are devastated by their loss. Unlike all parents, they make a terrible choice to keep him from leaving them entirely. It’s the parents’ grief and choices that then become the focal point of the book. The nation is experiencing a period of vast change. New buildings, new music, and new ideas are proliferating. Yet for Triss’s parents, it is vastly important that nothing change. They’re the people that would prefer to live in an intolerable but familiar situation rather than a tolerable unknown. Their love is a toxic thing, harming their children in the most insidious of ways. It takes an outsider to see this and to tell them what they are doing. By the end, it’s entirely possible that they’ll stay stuck until events force them otherwise. Then again, Hardinge leaves you with a glimmer of hope. The nation did heal. People did learn. And while there was another tragic war on the horizon, that was a problem for another day.

So what’s all that have to do with fairies? In a smart twist Hardinge makes a nation bereaved become the perfect breeding ground for fairy (though she never calls them that) immigration. It’s interesting to think long and hard about what it is that Hardinge is saying, precisely, about immigrants in England. Indeed, the book wrestles with the metaphor. These are creatures that have lost their homes thanks to the encroachment of humanity. Are they not entitled to lives of their own? Yet some of them do harm to the residents of the towns. But do all of them? Should we paint them all with the same brush if some of them are harmful? These are serious questions worth asking. Xenophobia comes in the form of the tailor Mr. Grace. His smooth sharp scissors cause Triss to equate him with the Scissor Man from the Struwwelpeter tales of old. Having suffered a personal loss at the hands of the otherworldly immigrants he dedicates himself to a kind of blind intolerance. He’s sympathetic, but only up to a point.

Terms I Dislike: Urban Fairies. I don’t particularly dislike the fairies themselves. Not if they’re done well. I should clarify that the term “urban fairies” is used when discussing books in which fairies reside in urban environments. Gargoyles in the gutters. That sort of thing. And if we’re going to get technical about it then yes, Cuckoo Song is an urban fairy book. The ultimate urban fairy book, really. Called “Besiders” their presence in cities is attributed to the fact that they are creatures that exist only where there is no certainty. In the past the sound of church bells proved painful, maybe fatal. However, in the years following The Great War the certainty of religion began to ebb from the English people. Religion didn’t have the standing it once held in their lives/hearts/minds, and so thanks to this uncertainty the Besiders were able to move into places in the city made just for them. You could have long, interesting book group conversations about the true implications of this vision.

There are two kinds of Frances Hardinge novels in this world. There are the ones that deal in familiar mythologies but give them a distinctive spin. That’s this book. Then there are the books that make up their own mythologies and go into such vastly strange areas that it takes a leap of faith to follow, though it’s worth it every time. That’s books like The Lost Conspiracy or Fly By Night and its sequel. Previously Ms. Hardinge wrote Well Witched which was a lovely fantasy but felt tamed in some strange way. As if she was asked to reign in her love of the fabulous so as to create a more standard work of fantasy. I was worried that Cuckoo Song might fall into this same trap but happily this is not the case. What we see on the page here is marvelously odd while still working within an understood framework. I wouldn’t change a dot on an i or a cross on a t.

Story aside, it is Hardinge’s writing that inevitably hooks the reader. She has a way with language that sounds like no one else. Here’s a sentence from the first paragraph of the book: “Somebody had taken a laugh, crumpled it into a great, crackly ball, and stuffed her skull with it.” Beautiful. Line after line after line jumps out at the reader this way. One of my favorites is when a fellow called The Shrike explains why scissors are the true enemy of the Besiders. “A knife is made with a hundred tasks in mind . . . But scissors are really intended for one job alone – snipping things in two. Dividing by force. Everything on one side or the other, and nothing in between. Certainty. We’re in-between folk, so scissors hate us.” If I had half a mind to I’d just spend the rest of this review quoting line after line of this book. For your sake, I’ll restrain myself. Just this once.

When this book was released in England it was published as older children’s fare, albeit with a rather YA cover. Here in the States it is being published as YA fare with a rather creepy cover. Having read it, there really isn’t anything about the book I wouldn’t readily hand to a 10-year-old. Is there blood? Nope. Violence? Not unless you count eating dollies. Anything remarkably creepy? Well, there is a memory of a baby changeling that’s kind of gross, but I don’t think you’re going to see too many people freaking out over it. Sadly I think the decision was made, in spite of its 11-year-old protagonist, because Hardinge is such a mellifluous writer. Perhaps there was a thought to appeal to the Laini Taylor fans out there. Like Taylor she delves in strange otherworlds and writes with a distinctive purr. Unlike Taylor, Hardinge is British to her core. There are things here that you cannot find anywhere else. Her brain is a country of fabulous mini-states and we’ll be lucky if we get to see even half of them in our lifetimes.

There was a time when Frances Hardinge books were imported to America on a regular basis. For whatever reason, that stopped. Now a great wrong has been righted and if there were any justice in this world her Yankee fans would line the ports waiting for her books to arrive, much as they did in the time of Charles Dickens. That she can take an event like WWI and the sheer weight of the grief that followed, then transform it into dark, creepy, delicious, satisfying children’s fare is awe-inspiring. You will find no other author who dares to go so deep. Those of you who have never read a Hardinge book, I envy you. You’re going to be discovering her for the very first time, so I hope you savor every bloody, bleeding word. Taste the sentences on your tongue. Let them melt there. Then pick up your forks and demand more more more. There are other Hardinge books in England we have yet to see stateside. Let our publishers fill our plates. It’s what our children deserve.

On shelves May 15th.

Source: Reviewed from British edition, purchased by self.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews:

- Here’s the review from The Book Smugglers that inspired me to read this in the first place.

- And here’s pretty much a link to every other review of this book . . . um . . . ever.

Spoiler-ific Interviews: The Book Smugglers have Ms. Hardinge talk about her influences. Remember those goofy television episodes from the 70s and 80s where dopplegangers would cause mischief. Seems they gave at least one girl viewer nightmares.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 5/1/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Scholastic,

Best Books,

multicultural fiction,

multicultural children's literature,

Varian Johnson,

Arthur A. Levine,

middle grade realistic fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle school fiction,

2014 realistic fiction,

middle school novels,

Add a tag

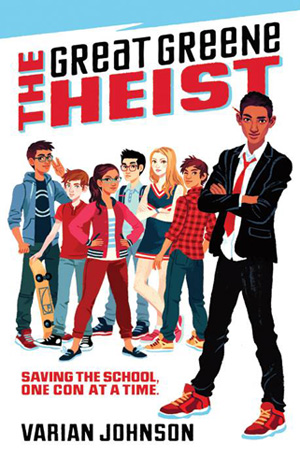

The Great Greene Heist

The Great Greene Heist

By Varian Johnson

Arthur A. Levine Books (an imprint of Scholastic)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-545-52552-7

Ages 10 and up

On shelves May 27th

What is the ultimate child fantasy? I’m not talking bubble gum sheets or wizards that tell you you’re “the chosen one”. Let’s think a little more realistically here. When a kid looks at the world, what is almost attainable but just out of their grasp for the moment? Autonomy, my friends. Independence. The ability to make your own rules and to have people fall in line. Often this dream takes the form of numerous orphan novels (it’s a lot easier to be independent if you don’t have any pesky parents swooping about), tales in which the child is some form of royalty (orphaned royalty, nine times out of ten), and other tropes. But for some kids, independence becomes a lot more interesting when it’s couched in their familiar, everyday, mundane world. Take middle school as one such setting. It’s a place a lot of kids know about, and it wouldn’t take much prodding for readers to believe that beneath the surface it’s a raging cesspool of corruption and crime. The joy of a book like The Great Greene Heist is manifold, but what I think I’ll take away from it best is author Varian Johnson’s ability to make this a story about a boy who knows how to do something very well (pulling cons) while also telling a compelling tale of a kid who knows what it means to be in charge and never abuses that power. If the ultimate child fantasy is to be in charge, the logical extension of that is to be the kind of person who is also a good leader. With that in mind, this book is poised to make a whole lotta kids very happy.

Since The Blitz at the Fitz the former con king Jackson Greene has gone straight. Trained in the art of conning by his own grandfather, Jackson’s the kind of guy you’d want on your side when things go down. Yet he seems perfectly content to put that all behind him, just tending the flowers of his garden club like he’s a normal kid or something. Normal, that is, before he gets wind that something shady is going on and it involves the upcoming school election. Gabriela de la Cruz (a.k.a. Gabby), the girl he inadvertently betrayed, is running for Class President against the ruthless Keith Sinclair. Worse? It looks like Sinclair and his dad have the principal in their pocket and that no matter what Gabby does she’ll be facing a defeat. Now it’s time for Greene to come out of retirement and assemble a crack team to use Keith and the principal’s worst instincts to their ultimate advantage. All it’s going to take is the greatest con Maplewood Middle School has ever seen.

To write a good con novel you have to be a writer confident in your own abilities. Johnson exudes that confidence, particularly when he takes risks. Since, at its essence, this is the story about a boy tricking a girl into doing what he wants, it would be easy for Johnson to slip up at any time and make the storyline either condescending or downright offensive. That he manages not to do this is nothing short of a minor miracle of modern writing. Much of this book is also actively engaged in the act of testing the reader’s sympathies. Johnson is misdirecting his readers as often as he is misdirecting his characters and he’s doing it with the given understanding that if they stick with the story they’ll be amply rewarded with more sympathetic motivations later on down the line. To do this in a book for kids is risky. You’re asking your readers to look at your hero as an antihero. And even if they’re sympathetic to his cause, will that translate into them continuing to read the book? In this case . . . yes.

One takeaway I took from this novel was the fact that Johnson really knows his age bracket. More to the point, he knows what kids today are really like. At first I found myself confused when I discovered that The Tech Club and The Gamer Club in this book were two very distinct and different entities. Under the old rules of middle school literature, anything that sniffed of video games or techie concerns would have been filed under “hopeless geekdom”. But in the 21st century we’re all geeks on some level. We’re all hooked up to our phones and computers. Big plot points in this book focus on the bribing of other kids with video games. The lines are blurring and at no point does anyone, even a bully, call another kid a nerd or geek. That isn’t to say that the bullies are nice or anything. It’s just that when it comes to base insults, some terms just don’t always carry the same cache. The nerds may make our toys but that still doesn’t mean a lot of us are going out and befriending them.

There’s been a lot of talk lately about the dearth of kids of color in books for children. Last year I tried to count as many middle grade books starring African-American boys and I topped out at around six or seven (and most of those were written by celebrities). With its truly multicultural cast (name me the last time you read a contemporary book for kids where TWO of the characters were Asian-American and not twins) and black boy hero dead front and center on the cover, we’re looking at a rare beast in the market. Author Varian Johnson also does a dandy job at avoiding certain tropes that librarians and teachers have grown to detest. For example, one way of making it clear what a character’s skin color is (or eye shape) is to compare them to food. I’m sure you’ve read your own fair share of books where the hero had “caramel colored skin” or “almond shaped eyes”. After a while you begin to wonder why the white kids aren’t being described as having “cottage cheese tinted cheeks” or “eyes as round as malted milk balls”. Johnson, for his part, is straightforward. When he wants to make it clear that someone’s black he just says they have “brown skin and black, curly hair”. See? How hard is that?

He also tackles casual racism with great skill and aplomb. At one point Jackson is facing the school’s senior administrative assistant. She says to him “Boys like you are always up to one thing or another.” Jackson’s response? “He hoped she meant something like ‘boys named Jackson’ or ‘boys who are tall,’ but he suspected her generalizations implied something else.” That is incredibly subtle for a middle school book. Some kids won’t pick up on it at all, while others will instantly understand what it is that Johnson is getting at. Because this character is minor (and her assumptions get neatly turned against her later) this storyline is not pursued, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t appreciated. Racism lives on long and strong in the modern world, but few authors for kids think it necessary to point out the fact. They should. It’s important.

Now you would think that since I walked into this knowing it was a kind of junior high Ocean’s 11 I’d have been on the lookout for the twist. All good con films have a twist. Sometimes the twist is good. Sometimes it’s unspeakably lame or capable of stretching your credulity to its limits. I am therefore happy to report that not only does The Great Greene Heist keep you from remembering that twist is coming, when it does come adult readers will be just as flummoxed by it as the kids.

If I were to change one thing about the book, it would be to include something additional. For some readers, keeping characters straight can be difficult. Johnson respects his readers’ instincts and intelligence, so he drops them almost mid-stream into the story. You have to get caught up with Jackson and Gabby’s falling out, and when we start our tale we’re in the aftermath of a once grand friendship. That’s fine, but had a character list been included in the beginning of the book as well, I would have had an easier time distinguishing between each new person we meet. I read this book in an early galley edition, so perhaps this problem will be changed by the time the book reaches publication, but if not then be aware that some readers may need a bit of help parsing the who is who right at the beginning.

You know, we talk a lot about the lack of diversity in our books for kids these days. There’s this two-headed belief that either kids won’t pick up a book with a kid of color on the cover and/or that such books are never fun. And certainly while it may be true that the bulk of multicultural literature for children does delve into serious subjects, there are exceptions to every rule. I look at this book and I think of Pickle by Kimberly Baker. I think of fun books that look amusing and will entice readers. Books that librarians and booksellers will be able to handsell with ease by merely describing the plot. With its fun cover, great premise, and kicky writing complete with twist, this book fulfills the childhood desire for autonomy while also knocking down stereotypes left and right. That it’s like nothing else out there for kids today is a huge problem. Let us hope, then, that it is a sign of more of the same to come.

On shelves May 27th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- Pickle by Kim Baker – Similar, but less a con novel than a pranking novel. Both types of stories require that the kids be in charge and the adults fall in line.

- The Fourth Stall by Chris Rylander – If The Great Greene Heist has an Ocean’s 11 feel then The Fourth Stall is The Godfather. Nothing wrong with that.

- Griff Carver, Hallway Patrol by Jim Krieg – A highly underrated novel and almost completely forgotten thanks to its gawdawful cover. But this joke on the hard-boiled cop genre definitely reminded me of the tone Varian Johnson set with his own book.

- You Killed Wesley Payne by Sean Beaudoin – Perhaps only because it features cliques as distinct entities vying for power, but that’s enough for me. But it’s YA so make note of that as well.

First Sentence: “As Jackson Greene sped past the Maplewood Middle School cafeteria – his trademark red tie skewed slightly to the left, a yellow No. 2 pencil balanced behind his ear, and a small spiral-bound notebook tucked in his right jacket pocket – he found himself dangerously close to sliding back into the warm confines of scheming and pranking.”

Notes on the Cover: Yes. Yes and also thank you. Now granted, the original cover was pretty cool. Seen here:

But at least they kept the same artist. Now it has more of a movie poster feel. Nothing wrong with that. As long as Jackson himself is front and center that is all I care. Good show, Scholastic. Way to knock it out of the park!

Other Blog Reviews:

Professional Reviews:

Misc:

- The book has become a bit of a touchstone for diversity discussions as of late. Thanks in large part to Kate Messner independent bookstores are all working to sell it in droves in what they’re calling The Great Greene Heist Challenge. Impressively, author John Green even offered ten signed copies of The Fault in Our Stars to any bookstore in the U.S. that handsells at least 100 copies of The Great Green Heist in its first month of publication. No small potatoes, that. I certainly hope lots and lots of people will be attempting to read and buy this one.

- Read the story behind the story here.

Video: As of this review there is no book trailer for this book. I hereby charge a middle school somewhere in this country to make an Ocean’s 11 style trailer out of it. Make it and I will post it, absolutely. For a guide, I direct you to this Muppet version of that very thing.

Okay. Now do that with this book.

The Mighty Odds

The Mighty Odds Lest we forget, this is an illustrated novel. Ignatow makes the somewhat gutsy choice of not explaining the art for a long time. Long before we even get to know Martina, we see her in various panels and spreads as an alien. In time, we learn that the art in this book is all her art, and that she draws herself as a Martian because that’s what her sister calls her. Not that you’ll know any of this for about 125 pages. The author makes you work to get at that little nugget of knowledge. By the way, as a character, Martina the artist is fascinating. She’s sort of the Luna Lovegood of the story. Or, as Nick puts it, “She had a sort of almost absentminded way of saying things that shouldn’t have been true but probably were.” There is one tiny flub in the art when Martina draws all the kids as superheroes and highlights Farshad’s thumbs, though at that point in the storyline Martina wouldn’t know that those are his secret weapons. Other than that, it’s pretty perfect.

Lest we forget, this is an illustrated novel. Ignatow makes the somewhat gutsy choice of not explaining the art for a long time. Long before we even get to know Martina, we see her in various panels and spreads as an alien. In time, we learn that the art in this book is all her art, and that she draws herself as a Martian because that’s what her sister calls her. Not that you’ll know any of this for about 125 pages. The author makes you work to get at that little nugget of knowledge. By the way, as a character, Martina the artist is fascinating. She’s sort of the Luna Lovegood of the story. Or, as Nick puts it, “She had a sort of almost absentminded way of saying things that shouldn’t have been true but probably were.” There is one tiny flub in the art when Martina draws all the kids as superheroes and highlights Farshad’s thumbs, though at that point in the storyline Martina wouldn’t know that those are his secret weapons. Other than that, it’s pretty perfect.

Thank you, Betsy, for this book recommendation. You’ve sold me! I am going to consider it for my YA lit class in the spring.

I also love how religion is portrayed as central to Joan’s life. Another book that does this is I Kill The Mockingbird.

I loved this book. Loved the writing, the characterizations, the realistic view of religion, the history, the everything. I think I would have loved it very much indeed when I was fourteen. I won’t compare it to Anne of Green Gables, however; I think it finds its equal in Emily of New Moon.

Hm. May be worthy of a post in and of itself. I’d forgotten Acampora’s book, but you’re completely right.

Oh do! It would be so nice for them. A good change of pace from the supernatural fare.

I noticed Kirkus actually paired it with your book, probably since both titles are about 2015 historical novels of girls escaping horrendous family situations. The Emily of New Moon comparison is VERY interesting to me. I actually eschewed my usual readalike portion at the end, if only because I couldn’t think of anything written recently to truly compare it to.

That’s cool!

My colleague and I had a very similar, yet abbreviated version of your review as our takeaway from this brilliant book. How courageous to write of faith in such an engaging way. It’s a journal of a year in a young woman’s life and Schlitz’s inspiration was one of her own grandmother’s journals. The journal format affords an insight into the awareness of this young woman that is completely captivating. Yes, the book burning was the last straw, and, there are many women of an age who saw through their mother’s own lives, warnings about the realities of lives of women, who then endeavor to blaze a more self-satisfying trail.

The Hired Girl is one of the best books I’ve ever read and now it’s one of my favorite books. I suggest this book to many readers.

Just finished it last night. I loved Splendors and Glooms and didn’t think I could love this book as much, but I did love it, in a different way. It made me think about parents, and siblings, and what life would be like without them…which is a sad thing to think about, but also affirming.