This week, we're shining the spotlight on another one of our Place of the Year 2015 shortlist contenders: Cuba.

The post Place of the Year 2015 nominee spotlight: Cuba appeared first on OUPblog.

This week, we're shining the spotlight on another one of our Place of the Year 2015 shortlist contenders: Cuba.

The post Place of the Year 2015 nominee spotlight: Cuba appeared first on OUPblog.

Driven by enthusiasm and a can-do attitude, artists want to grow Cuba's underdeveloped animation industry.

Add a Comment

It’s in the grip of North American winter that I often dream of escape to warmer climates. Thanks to the WordPress.com Reader and the street photography tag, I can satisfy my travel yen whenever it strikes. Here are just some of the amazing photos and photographers I stumbled upon during a recent armchair trip.

My first stop was Alexis Pazoumian’s fantastic SERIES: India at The Sundial Review. I loved the bold colors in this portrait and the man’s thoughtful expression.

Speaking of expressions, the lead dog in Holly’s photo from Maslin Nude Beach, in Adelaide, Australia, almost looks as though it’s smiling. See more of Holly’s work at REDTERRAIN.

In a slightly different form of care-free, we have the muddy hands of Elina Eriksson‘s son in Zambia. I love how his small hands frame his face. The gentle focus on his face and the light in the background evoke warm summer afternoons at play.

Heading to Istanbul, check out Jeremy Witteveen‘s fun shot of this clarinetist. Whenever I see musicians, I can’t help but wonder about the song they’re playing.

Pitoyo Susanto‘s lovely portrait of the flower seller, in Pasar Beringharjo, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, captivated me. Aren’t her eyes and her gentle smile things of beauty?

Arresting in a slightly different fashion is Rob Moses‘ Ski Hill Selfie, taken in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The juxtaposition of the bold colors and patterns in the foreground against the white snow in the background caught my eye.

Further under the category of fun juxtaposition, is Liu Tao’s photo of the elderly man in Hafei, China, whose fan reminds me of a punk rock mohawk.

From Hafei, we go to Havana, Cuba, and Edith Levy‘s beautifully ethereal Edificio Elena. I found the soft pastels and gentle shadows particularly pleasing. They lend a distinctly feminine quality to the building.

And finally, under the category of beautiful, is Aneek Mustafa Anwar‘s portrait, taken in Shakhari Bazar, Old Dhaka, Bangladesh. The boy’s shy smile is a wonderful representation of the word on his shirt.

Where do you find photographic inspiration? Take a moment to share your favorite photography blogs in the comments.

In 1968, as the world convulsed in an era of social upheaval, Cuba unexpectedly became a destination for airplane hijackers. The hijackers were primarily United States citizens or residents. Commandeering aircraft from the United States to Cuba over ninety times between 1968 and 1973, Americans committed more air hijackings during this period than all other global incidents combined. Some sought refuge from petty criminal charges. A majority, however, identified with the era’s protest movements. The “skyjackers,” as they were called, included young draft dodgers seeking to make a statement against the Vietnam War, and Black radical activists seeking political asylum. Others were self-styled revolutionaries, drawn by the allure of Cuban socialism and the nation’s bold defiance of US domination. Havana and Washington, diplomatically estranged since 1961, maintained no extradition treaty.

But Cuba was an imperfect site for the realization of American skyjacker dreams. Although the surge in hijackings paralleled the warm relations between the Cuban government and US organizations such as the Black Panther Party and Students for a Democratic Society, leftwing skyjackers were not always welcome in Cuba. Many were imprisoned as common criminals or suspected CIA agents. The mutual discomfort of the United States and Cuban governments over the hijacking outbreak resulted in a rare diplomatic collaboration. Amidst the Cold War stalemate of the Nixon-Ford era, skyjackers inadvertently forced Havana and Washington to negotiate. In 1973, the two governments broke their decade-old impasse to produce a bilateral anti-hijacking accord. The hijacking episode of 1968-’73 marks the unlikely meeting point where political protest, the African American freedom struggle, and US-Cuba relations collided amid the tumult of the sixties.

For a generation of Americans radicalized by the Civil Rights era and the Vietnam War, Cuba’s social gains in universal healthcare, education, and wealth redistribution — campaigns disproportionately supported by Afro-Cubans — had made the Cuban Revolution a beacon of inspiration for the United States. Left. By 1970, several thousand Americans, traveling independently or with organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, had visited Cuba to witness its transformation up-close. But skyjackers sometimes perceived Cuba in terms that echoed age-old paternalistic tropes about the island, as admiration blurred into entitlement. Cuba, they insisted, should welcome them as revolutionary comrades instead of locking them in jail. Nonetheless, some US skyjackers had fled from circumstances that suggested genuine political repression. Black radical activists, in particular, were often successful in appealing to Cuban officials for political asylum after arriving as skyjackers. The Cuban government allowed these asylees to make lives for themselves in Havana, paying for their living expenses as they transitioned to Cuban society or attended college. Several members of the Black Panther Party, such as William Lee Brent, and members of the Republic of New Afrika, such as Charlie Hill, became long-term residents of Havana.

Hijackers inadvertently forced Washington to face the consequences of American exceptionalism. Cuban émigrés reaching US soil with “dry feet” had been granted sanctuary and accorded a fast-track to citizenship since 1966, when the Cuban Refugee Adjustment Act created a powerful incentive for Cubans to immigrate by any available means, including violence and hijacking, an enticement that Havana had repeatedly protested. Now, Cuba was granting sanctuary to Americans committing similar crimes. The irony was not missed by the State Department. As Henry Kissinger admitted, the United States was now seeking to negotiate with Havana what Washington had earlier refused to negotiate in the aftermath of the Cuban revolution, when Cubans were hijacking planes and boats to the United States and Havana had appealed unsuccessfully to US officials for the return of the vessels. The island’s attractiveness as a legal sanctuary for Americans was in large part a consequence of Washington’s policy of unrelenting hostility, which had severed the normal ties through which the two nations might collaborate, as diplomatic equals, to resolve an issue such as air piracy.

Air hijackings to Cuba declined dramatically after the accord of 1973. A shallow crack appeared in the diplomatic stalemate between Washington and Havana, setting the stage for the mild warming of US-Cuba relations during the coming Carter era. But while mutual cooperation to respond to the hijacking outbreak preceded the brief détente of the late 1970s, air piracy did not itself cause the Cold War thaw. Rather, the significance of hijacking to US-Cuba relations lies in the way in which skyjackers, as radical non-state actors driven by idealism and politics, influenced the terrain of state relations in ways that no one could have anticipated. So too, by granting formal political asylum to Americans, especially African American activists charging racist repression, Havana defied US claims to moral and legal authority in the arena of human rights. As US-Cuba relations now make a historic move toward normalization, it is likely that non-state actors will continue to play unforeseen roles, defying both US and Cuban state power.

Headline image credit: Map of Cuba. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cold War air hijackers and US-Cuban relations appeared first on OUPblog.

How did the international community get the response to the Ebola outbreak so wrong? We closed borders. We created panic. We left the moribund without access to health care. When governments in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Senegal, Guinea, Mali, and Nigeria called out to the world for help, the global response went to mostly protect the citizens of wealthy nations before strengthening health systems on the ground. In general, resources have gone to guarding borders rather than protecting patients in the hot zone from the virus. Yet, Cuba broke this trend by sending in hundreds of its own health workers into the source of the epidemic. Considering the broader global response to Ebola, why did Cuba get it so right?

Ebola impacted countries, and the World Health Organization (WHO), called out for greater human resources for health. While material supplies arrived, many countries tightened travel restrictions, closed their doors and kept their medical personnel at home. At a time when there has never been greater knowledge, more money, and ample resources for global health, the world responded to an infectious pathogen with some material supplies, but also with securitization, experimental vaccines, and forced quarantines – all of which oppose accepted public health ethics. The result is that without human resources for health on the ground, the supplies stay idle, the vaccines remain questionable, and the securitization instills fear.

The Global North evacuated their infected citizens. These evacuations spawned donations to the WHO and then led to travel bans. The United Kingdom provided £230 million in material aid to West Africa. The United States committed $175 million to combat the virus by transporting supplies and personnel, with an estimated 3,000 soldiers to be involved in the response. Canada’s government provided some $35 million to Ebola, including a mobile testing lab, sanitary equipment and 1,000 vials of experimental vaccines that have yet to arrive in West Africa or even be tested on humans. Canada then followed the example of Australia, North Korea, and other nervous nations, in imposing a visa ban on persons traveling from Ebola affected countries. Even Rwanda imposed screening on Americans because of confirmed cases in the United States.

Despite this global trend, Cuba — a small and economically hobbled nation — chose to make a world of difference for those suffering from Ebola by sending in 465 health workers, expanding hospital beds, and training local health workers on how to treat and prevent the virus. Cuba is the only nation to respond to the call to stop the Ebola epidemic by actually scaling up health care capacity in the very places where it is needed the most. Even with a Gross Domestic Product per capita to that of Montenegro, Cuba has proven itself as a global health power during the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Many scholars and pundits have been left wondering not only how a low-income country, with its own social and economic challenges, could send impressive medical resources to West Africa, but also why they would dive into the hot zone in the first place — especially when nobody else dares to do so.

Cuba is globally recognized as an outstanding health-care power in providing affordable and accessible health services to its own citizens and to the citizens of 76 countries around the world, including those impacted by Ebola. Cuba’s health outreach is grounded in the epistemology of solidarity — a normative approach to global health that offers a unique ability of strengthening the core of health systems through long-term commitments to health promotion, disease prevention and primary care. Solidarity is a cooperative relationship between two parties that is mutually transformative by maximizing health-care provision, eroding power structures that promote inequity, and by seeking out mutual social and economic benefit. The reason for the general amazement and wonder over Cuba’s Ebola-response stems from a lack of depth in understanding the normative values of solidarity, as it is not a driving force in the global health outreach by most wealthy nations. The ethic of solidarity can even be seen on the ground in West Africa with Cuban doctors like Ronald Hernandéz Torres posting photos of his Ebola team wearing the protective gear, while giving the thumbs and peace sign — an incredible snapshot of humanity that contrasts the typically frightening images of Ebola health workers.

Solidarity is not charity. Charity is governed by the will of the donor and cannot be broad enough to overcome health calamities at a systems level. Solidarity is also not pure altruism. Selfless giving is based on exceptional, and often short-term, acts for no expectation of reward or reciprocity. For Cuba, solidarity in global health comes with the expectation of cooperation, meaning that the recipient nation should offer some level of support to Cuba, be it financial or political. Solidarity also means that there is a long-term relationship to improve the strength of a health system. Cuba’s current commitment to Ebola could last months, if not years.

Cuba’s global health outreach can be approached through the lens of solidarity. This example implies engaging global health calamities with cooperation over charity, with human resources in addition to material resources, and ultimately with compassion over fear. This approach could well be at the heart of wiping out Ebola — along with every other global health calamity that continues to get the best of us because we have not yet figured out how to truly take care of each other.

Heading image: Ebola treatment unit by CDC Global. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Global solidarity and Cuba’s response to the Ebola outbreak appeared first on OUPblog.

It is December 1939. In a lavish apartment in Antwerp, Belgium, 9-year-old Claudia Rossin, along with her parents, relatives and others, are listening to a Polish refugee taking about the Nazi invasion of Poland and the horrors that they brought with them. But Claudia doesn't fully understand the implications of Anton's story. She is far too wrapped up in her unhappiness at being under the thumb of a detested French governess whose job it was to turn a very head-strong girl into a perfect social being.

|

| Teenage sweethearts Felicia and Edmundo Desnoes age 16 in Havana, Cuba |

The Wild Book Margarita Engle

Homework Fear

The teacher at school

smiles, but she's too busy

to give me extra help,

so later, at home,

Mama tries to teach me.

She reminds me

to go oh-so-slowly

and take my time.

There is no hurry.

THe heavy book

will not rise up

and fly away.

When I scramble the sneaky letters

b and d, or the even trickier ones

r and l, Mama helps me learn

how to picture

the sep--a--rate

parts

of each mys--te--ri--ous

syl--la--ble.

Still, it's not easy

to go so

ss--ll--oo--ww--ll--yy.

S l o w l y.

SLOWLY!

I have to keep

warning myself

over and over

that whenever I try

to read too quickly,

my clumsy patience

flips over

and tumbles,

then falls...

Why?

Wwhhyyyy?

WHY?

¡Ay!

The doctor hisses Fefa's diagnosis like a curse-- word blindness*. She'll never read, or write. It's why she hates school so much, why the other kids taunt her when she has to read OUT LOUD.

But Fefa's mother has the heart of poet and doesn't accept the prognosis. She gives Fefa a blank book (one of the most terrifying things Fefa has seen) for her to fill with words as she gets them, slowly.

Fefa deals with the bullying and taunts of her classmates and siblings and slowly fills her book and slowly learns to detangle the letters.

Y'all know I'm a huge Engle fan. I'm most familiar with her YA stuff, but this one is more middle grade. There's a lot less politics and history**, as the main focus is Fefa's struggle with the written word. It's based on Engle's own grandmother and the stories she told of her own struggle with dyslexia.

Of course, one of the things that I like so much about Engle is how she weaves stories around Cuban history, so this wasn't my favorite one of hers. Also, there's only one narrator, while I'm used to her work being told in multiple voices. THAT SAID, it's still really good.

I like how Engle works with free verse and structure in this one to really capture Fefa's voice, especially when sounding words out and trying to figure out syllables. It's one that younger readers will enjoy and will cause them to seek out more of her work.

Today's Poetry Friday Round-up is over at... A Teaching Life. Be sure to check it out!

*Apparently, this is actually what they used to call dyslexia.

**Although it is set in 1912 Cuba and there is still some historical drama, it's just not the focus like it is in her other work.

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

I’m starting a rather informal summer series. (By definition, shouldn’t all summer series be informal?) I’m finding people who are spending part of their summer exploring a new culture, learning a new technology or experiencing something new and unusual and I’m asking them to write about it and then share it here. I have a few posts lined up and am always looking for more!The series is starting here today with a wonderful piece from my dear friend, Susan Adams who recently had the opportunity to visit Cuba. She was excited to go and I was so excited for her! I know her well enough to know she would fully experience Cuba and all it has to offer and that she would come home with keen observations. I know she has stories too! I can’t wait to meet up with her in Indy and here her stories!!

The following are her reflections.

I was recently privileged to travel to Cuba with a small group of faculty members from Butler University where I am a faculty member in the College of Education. I have long been fascinated by Cuba and have thought often of what I heard from 2 undergraduate professors, the first of which was a Cuban attorney turned foreign language professor and the second of which had been a young college student studying in Cuba as Fidel Castro rose to power in the 1950’s. The Cuban attorney was bitter, frustrated and angry about how his life in the U.S. had turned out; frankly he did a lot of ranting and raving about history and politics, most of which went over our heads, but seemed to soothe him because he generally would cease his rant with a cool smile. The other professor intrigued me even more because her eyes lit up and she smiled a dreamy smile as she described the charisma and intelligence of Fidel Castro, almost forgetting herself as she mentally relived the excitement of being in Cuba at such a momentous time in history.

What I learned from my professors clashed in contrast with my mother’s recollection of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the stark terror my mother remembers experiencing whenever my father went to sea as a young Navy soldier. My father was frequently on the ships patrolling the Caribbean; the uncertainty of his exact location and the daily news reports made her fearful she would be left a young widow with a baby. When I told my mother I was going to Cuba, she attempted to mask the flood of these old emotions (failing completely, of course) and tried to pretend she did not think I was crazy for wanting to go. I have a nasty habit of traveling to parts of the world that scare my mom (Mexico, Honduras, and most recently, Bangkok) but she tries valiantly to be happy for me in spite of her fears.

How to describe what I saw and experienced was constantly on my mind as we traveled to Havana, Santa Clara and Varadero, spending hours and hours aboard an old 1970’s Thomas school bus imported from Canada. It is easy to describe the lush, green, tropical beauty of the island. Yes, of course, it was very hot there (one day the temperature reached in excess of 97 degrees Fahrenheit with 100% humidity)so being sweaty even when you are doing nothing at all is normal. Eating beautiful and sometimes unfamiliar fruits and vegetables (malanga, a tuber sort of like the potato, was a favorite discovery) was a great adventure-mango for breakfast almost every day makes me SO happy! Visiting Che Guevara’s mausoleum was deeply touching and strangely inspiring. Swimming in the ocean at Varadero was amazing and beautiful on the white sand beach under the blazing sun and at night under a full moon, waving our hands to see flashes of phosphorescent microscopic creatures. These are the easy things to describe.

What is more difficult is to characterize the beautiful, resourceful, inventive and generous people that we met. Each day we listened to an expert in some field (economics, social sciences, folklore, education, organic farming, etc.). As I listened, it was impossible to

Life: An Exploded Diagram by Mal Peet, Candlewick, 2011, 416 pp, ISBN: 076365227X

The Firefly Letters: A Suffragette's Journey to Cuba by Margarita Engle, Henry Holt and Co, 2010, 160 pp, ISBN: 0805090827

In 1953, Castro had led an attack on a Cuban army barracks hoping to launch a revolt against the government of Fulgencio Batista. That attack failed and he was arrested and imprisoned, though later released in an amnesty of political prisoners. Castro and his brother Raúl formed a small rebel group and hid in Cuba’s eastern mountains as they gathered more supporters, trained them to fight, and connected with other anti-Batista groups. By late 1958, the rebel forces were advancing westward. On January 1, 1959, Batista fled the country and Castro entered Havana triumphant.

The initial provisional government included leaders from several rebel factions, not just Castro’s. At first, he refrained from taking any political power, although he was commander of the armed forces. In six weeks, though, the provisional prime minister—not a Castro ally—resigned, and he took the office.

During 1959, Castro supporters, including Raúl, filled more and more top-level positions. Meanwhile, hundreds of former Batista officials were tried and executed, and Castro began sending signals that he was a Communist. An exodus of thousands of Cubans began, some fearing for their lives because of links to Batista, others angered by Castro’s refusal to restore the 1940 constitution and hold promised elections. Cuban relations with the United States worsened when Castro seized the assets of several American companies and tilted toward the Soviet Union; they fractured when the U.S. government cancelled trade agreements and backed an invasion by anti-Castro Cubans, which failed miserably. By early 1962, Castro had announced that his revolution was socialist, and the United States had placed an embargo on trade with the island.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

Carmen T. Bernier-Grand, illustrated by Raúl Colón,

Alicia Alonso: Prima Ballerina

Marshall Cavendish, 2011.

Ages 10+

Alicia Alonso, the latest in a series of portraits of Latin figures by award-winning author and poet Carmen Bernier-Grand, is written in lyrical free verse, a style that particularly suits the dramatic life of this beloved Cuban dancer.

Alonso’s long career has been marked by many difficulties. Already a highly regarded dancer in Cuba, she and her young fiancé, also a dancer, immigrated to New York in 1937, when Alicia was 15 and pregnant. She resumed ballet as soon as her daughter was born. In a field known to destroy bodies and careers early in life, Alonso continued dancing until she was in her seventies, despite diminishing vision from a detached retina that led eventually to blindness.

Bernier-Grand tells the story in touching word-sketches of key moments in Alonso’s life: selection for the role of Swanilda in Coppélia; romance with Fernando Alonso, her eventual husband; parental disapproval of ballet as a career; separation from her daughter during her U.S. tours; learning Giselle while blind and hospitalized by using her fingers as her feet; ballet shoes stuck to her feet with dried blood; eventual refusal to dance in Cuba while Batista was in power.

“She counts steps, etches the stage in her mind.

Spotlights of different colors warn her

she is too near the orchestra pit.

She moves, a paintbrush on canvas…

She imagines an axis

and pirouettes across her own inner stage.”

Raúl Colón’s stylized pastel illustrations poignantly evoke ballet’s beauty and Alonso’s suffering, despite which she has had one of the longest, most esteemed careers in ballet history. Vision in one eye was partially restored in 1972. Alonso, who founded the Ballet Nacional de Cuba, still choreographs dances at age 92.

Back matter includes a detailed biographical narrative of Alonso’s life; lists of some of the ballets she has danced and choreographed and awards she has won; a glossary; an extensive bibliography of sources and websites; and notes on the text. While the simple story of the ballerina’s life will appeal even to very young children, the reference material is rich enough for an older child to use for a research project. In the process of understanding a woman artist’s life struggles, young readers will also learn much about U.S.-Cuban relations.

Charlotte Richardson

February 2012

Fresh stamps from our good friend Wes, this time from Cuba commemorating the 1970 World Expo in Osaka, Japan.

Towards better understanding

To the better enjoyment of life

Planning a more satisfying life

Also worth viewing…

1962 Denmark Christmas Seals

Portugal 1981 Census Stamps

Hong Kong Festivals 1975 Stamps

Like what you see?

Sign up for our Grain Edit RSS feed. It’s free and yummy! YUM!

©2009 Grain Edit - catch us on Facebook and twitter

This short video story on the BBC is ostensibly about the influence of Soviet animation on Cuban kids between the 1960s and ’90s, but it also offers an all-too-brief glimpse of the Cuban animation industry. Does anyone know if it’s filmed in a school or a studio?

(Thanks, Simon Acosta)

Cartoon Brew: Leading the Animation Conversation |

Permalink |

No comment |

Post tags: Cuba

Earlier this year I blogged about Primary Source when they hosted a Global Read of Mitali Perkins‘ book Bamboo People. On March 2nd Primary Source will be hosting a new Global Read, this time focusing on Christina Diaz Gonzalez‘ YA book The Red Umbrella. The online discussion forum will be followed by a live web-based session with Christina on March 9th from 3:00 – 4:00pm EST. Anyone interested in global issues is welcome to take part in this free event but must register online here.

Earlier this year I blogged about Primary Source when they hosted a Global Read of Mitali Perkins‘ book Bamboo People. On March 2nd Primary Source will be hosting a new Global Read, this time focusing on Christina Diaz Gonzalez‘ YA book The Red Umbrella. The online discussion forum will be followed by a live web-based session with Christina on March 9th from 3:00 – 4:00pm EST. Anyone interested in global issues is welcome to take part in this free event but must register online here.

The Red Umbrella follows a 14-year-old Cuban girl and her brother sent by their parents to live in the United States during the tumultuous period of 1960s Cuba. Christina says the story was ” loosely based on the experiences of my parents, mother-in-law and many of the other 14,000 children who participated in Operation Pedro Pan.”

Talking about why she wrote the book, Christina says:

“Obviously, this is a personal story and part of my family history. In fact, it’s an important part of American history and yet there wasn’t much written about it, especially from the point of view of the children who experienced it. The book showcases how the U.S. has always been a haven for those seeking refuge from injustice and oppression and how average Americans have stepped up to help those in need, even if they were foreigners in our country. I also wanted to show the pride immigrants (in this case Cubans) have for their homeland, but how, in the end, family is what matters most… home is not a physical place. It’s where you feel you belong, where you are surrounded by people who love and accept you.”

The Red Umbrella has been appearing on many YA book lists since being published in May 2010, including ALA/YALSA’s 2011 Best Fiction for Young Adults. You can read an interview with Christina here, and there is also an amazing book trailer made by Christina’s brother-in-law:

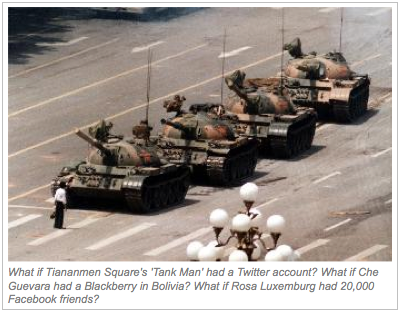

Western observers have been celebrating the role of Twitter, Facebook, smartphones, and the internet in general in facilitating the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak in Egypt last week. An Egyptian Google employee, imprisoned for rallying the opposition on Facebook, even became for a time a hero of the insurgency. The Twitter Revolution was similarly credited with fostering the earlier ousting of Tunisia’s Ben Ali, and supporting Iran’s green protests last year, and it’s been instrumental in other outbreaks of resistance in a variety of totalitarian states across the globe. If only Twitter had been around for Tiananmen Square, enthusiasts retweeted one another. Not bad for a site that started as a way to tell your friends what you had for breakfast.

But skeptics point out that the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square continued to grow during the five days that the Mubarak government shut down the internet; that only nineteen percent of Tunisians have online access; that while the Iran protests may have been tweeted round the world, there were few Twitter users actually in-country; and that although Americans can’t seem to survive without the constant stimulus of digital multitasking, much of the rest of the world barely notices when the cable is down, being preoccupied instead with raising literacy rates, fighting famine and disease, and finding clean water, not to mention a source of electricity that works for more than an hour every day or two.

But skeptics point out that the crowds in Cairo’s Tahrir Square continued to grow during the five days that the Mubarak government shut down the internet; that only nineteen percent of Tunisians have online access; that while the Iran protests may have been tweeted round the world, there were few Twitter users actually in-country; and that although Americans can’t seem to survive without the constant stimulus of digital multitasking, much of the rest of the world barely notices when the cable is down, being preoccupied instead with raising literacy rates, fighting famine and disease, and finding clean water, not to mention a source of electricity that works for more than an hour every day or two.

It’s true that the internet connects people, and it’s become an unbeatable source of information—the Egyptian revolution was up on Wikipedia faster than you could say Wolf Blitzer. The telephone also connected and informed faster than anything before it, and before the telephone the printing press was the agent of rapid-fire change. All these technologies can foment revolution, but they can also be used to suppress dissent.

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt, a switch that shuts it all down. Cuba is a country well-known for blocking digital access, but responding to events in Egypt and the small but scary collection of island bloggers, El Lider’s government is sponsoring a dot gov rebuttal, a cadre of official counterbloggers spreading the party line to the still small number of Cubans able to get online—about ten percent can access the official government-controlled ’net—or get a cell phone signal in their ’55 Chevys.

You don’t have to master the laws of physics to observe that for every revolutionary manifesto there’s an equal and opposite volley of government propaganda. For every eye-opening book there’s an index librorum prohibitorum—an official do-not-read list—or worse yet, a bonfire. For every phone tree organizing a protest rally there’s a warrantless wiretap waiting to throw the rally-goers in jail. And for every revolutionary internet site there’s a firewall, or in the case of Egypt, a switch that shuts it all down. Cuba is a country well-known for blocking digital access, but responding to events in Egypt and the small but scary collection of island bloggers, El Lider’s government is sponsoring a dot gov rebuttal, a cadre of official counterbloggers spreading the party line to the still small number of Cubans able to get online—about ten percent can access the official government-controlled ’net—or get a cell phone signal in their ’55 Chevys.

All new means of communication bring with them an irrepressible excitement as they expand literacy and open up new knowledge, but in certain quarters they also spark fear and distrust. At the very least, civil and religious authorities start insisting on an imprimatur—literally, a permission to print—to license communication and censor content, channeling it al

The Firefly Letters by Margarita Engle

I have adored Engle and her poetry since first reading her Poet Slave of Cuba. This historical novel told in verse tells the story of early Swedish feminist Fredrika Bremer and her travels in Cuba. While in Cuba she inspires and changes the lives of two women, a slave named Cecilia and a wealthy young woman named Elena. At first amazed and shocked by the freedom Fredrika demonstrates, Elena warms to her as she begins to understand that the future could be different than just an arranged marriage. Cecilia finds in Fredrika a woman who looks beyond her slave status and a role model for hope. Told in Engle’s radiant verse, this is another novel by this splendid author that is to be treasured.

As with all of her novels, Engle writes about the duality of Cuba: the dark side and the light, the beauty and the ugliness. Once again she explores the horrific legacy of slavery without flinching from its truth. Against that background of slavery, she has written a novel of freedom. It is the story of a woman who refused to be defined by the limitations of her birth and her sex, instead deciding to travel and write rather than marry. Fredrika is purely freedom, beautifully contrasted with the two women who are both captured in different ways and forced into lives beyond their control.

Beautifully done, this book is an excellent example of the verse novel. Each poem can stand on its own and still works to tell a cohesive story. At times Engle’s words are so lovely that they give pause and must be reread. This simply deepens the impact of the book. Engle also uses strong images in her poems. In this book, fireflies are an important image that work to reveal light and dark, as well as freedom and captivity.

Highly recommended, this author needs to be read by those who enjoy poetry, those who enjoy history, and those who simply are looking for great writing. Appropriate for ages 11-14.

Reviewed from library copy.

Add a Comment

Julia E. Sweig, is the Nelson and David Rockefeller Senior Fellow for Latin American Studies and Director for Latin American Studies the Council on Foreign Relations. Her most recent book,

Cuba: What Everyone Needs to Know, is a concise and remarkably accessible portrait of the small island nation’s unique place on the world stage over the past fifty years. The book is presented in question and answer format and below we have excerpted a question about Cuba under the Bush administration.

What were the main features of U.S. policy toward Cuba under George W. Bush and how did Cuba respond?

As the United States entered the new millennium, Elián fatigue, embargo fatigue, and widespread annoyance with the domestic politics of the Cuba issue had helped create a bipartisan consensus in favor of dramatic policy change. No one necessarily thought this would be easy…Still, the momentum for policy change continue into the next year, when the GOP-controlled House of Representatives voted to end trade and travel restrictions. By then, however, the Bush White House had made clear its intention of vetoing any such legislation.

Nonetheless, for most of 2002, Havana gingerly probed for evidence that it was possible to reach a modus vivendi with Washington. Raul Castro offered to return detainees from the war in Afghanistan to Guantánamo in the event they tried to escape…Even in the wake of early 2002’s specious accusations regarding Cuba’s supposed potential to develop and proliferate technology for bioweapons, the Cuban government still permitted President Carter’s historic visit in May and allowed the Varela Project petition to be submitted without significant incident. This gesture would mark the high point of their generosity, however.

Beginning in early 2003, the Bush administration set out to largely undo the people-to-people openings launched by the Clinton administration. Acquiring or renewing a license for NGO-sponsored or educational travel became more difficult…Soon, almost all of the legal travel categories created under the rubric of “supporting the Cuban people” had been eliminated.

Yet it was the run-up to the war in Iraq and the new mantra or preemptive security that really shook Havana’s expectations of the Bush White House. One dimension of the Castro government’s efforts to cultivate positive vibes in Washington had been its relative tolerance of a variety of dissident groups (many of which had been infiltrated), from small scale to higher profile. Congressional delegations visiting Havana could return to their districts and to Washington having met with such individuals, lending their visits, which often explored possible commercial ties with the regime, an air of human rights credibility. But the benefits of allowing such oxygen evaporated once Washington started to advance its regime change agenda with military power, albeit in Iraq. Havana reasoned that allowing the groups to continue to function could also give an in-road to an enemy whose designs may well turn belligerent. Thus, in the eyes of Cuban officials, the national security prerogatives of cracking down on domestic opposition activists were well worth the near-universal international backlash Cuba was likely to (and did) incur…

Several months later, President Bush launched the Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba (CAFC), a new interagency initiative chaired by a series of cabinet officials. The commission’s recommendations offered few surprises: Keep sanctions in place, step up efforts to penetrate the government’s “information blockade,” interrupt any moves by a successor regime to replace Fidel Castro, but offer assistance to a transitional government willing to hold elections, release political prisoners, and adopt the marks of freedom stipulated by Helms-Burton. In the scenarios envisioned by the commission’s first 500-page report, an American “transition coordinator” (a position created soon after at the State Department) would judge when conditions in post-Castro Cuba would make it eligible for aid and other accoutrements that accompany a U.S. seal of approval.

One policy change to emerge from the commission’s work was the president’s move, notably in 2004, an election year, to massively scale back Cuban American family travel and remittances. Since 1999, Cuban Americans had been permitted to travel annually to the island to visit any member of their extended family. The new regulations cut these visits to once every three years, and only to see immediate family. New restrictions on remittances reduced the legal quantity that could be sent and also stipulated that only immediate family would be eligible to receive such transfers. Previously, they could be sent to “any household.”

Measuring the impact of these changes with any certainty is nearly impossible. In 2006, the CAFC could only claim that the new policies had reduced remittances “significantly.” Yet while Cuban families certainly felt the pinch, there was no appreciable effect on the Cuban regime’s capacity to stay in power or repress its citizens…In the same period, Washington denied virtually all requests by Cuban professionals to travel to the United States unless applicants could claim they had been victims of political persecution by the regime…In 2004, the United States also called a halt to the twice-annual migration talks because the meetings allegedly gave the appearance that the United States conferred legitimacy upon the Cuban government. Cuba’s annual allotment of 20,000 migration visas continued, but human smuggling in the Gulf of Mexico did as well.

In response to these meetings, Cuba reduced its public relations campaigns around lifting the embargo, convinced that they were not, for the moment, worth the effort. Guantánamo once again became a tool to mobilize domestic nationalism. Initially, Cuba’s security establishment had hoped to show off its national security bona fides by tolerating the base’s conversion into a detention center for suspected terrorists. Yet as allegations of torture surfaced and the legality of the detentions came into questions, Guantánamo became, as it did for many of America’s global critics, a symbol of American imperial hubris, one which in the Cuban case also allowed Havana to highlight the island’s own history of grievances over American violations of its sovereignty. At the same time, fully cognizant of George W. Bush’s bellicosity, the Cuban government appeared to cautiously avoid dramatic provocations of the sort that could lead to a repeat of past migration crises or the 1996 shoot-down.

Among the last public gestures of goodwill under the George W. Bush administration was Fidel Castro’s offer to send hundreds of medical professionals and disaster relief workers to New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. But Washington wrote off the offer as a publicity stunt. The embarrassing prospect that Fidel’s teams of doctors and nurses might have something to contribute to New Orleans residents outweighed any calculus that could actually deliver help to Katrina’s victims.

Leonardo Padura. Translated by Peter Bush. Havana Fever. London (UK): Bitter Lemon Press, 2009.

ISBN: 978-1-904738-36-7

Havana Fever burns with resentment that Cuba’s ruined culture shows itself in every vestige of its modern form. Whole barrios given over to crime and desperation, a city whose collapsed and patchwork buildings reflect society’s structural failure that began with Batista’s overthrow. Decaying mansions are little different from outrageous underclass brothels, the one stripped of anything saleable, the other sold out by the revolution. There’s no love lost between Leonardo Padura and official Cuba. But these things have become commonplaces of Cuban exile writers.

Today, the Count sells books and leaves the world as he finds it, to its own devices. But out of the blue, a gut feeling burns through his chest when he stumbles upon a Cuban equivalent of the ancient Library of Alexandria.

The novel will delight bibliophiles with its description of the Montes de Oca library: the earliest book published in Cuba, nineteenth century treatises featuring hand colored engraved plates, first editions of laureates of Cuban poetry—autographed. Conde could defraud the clueless owners but instead gives them a fair price, and points out the rarest volumes that must not be sold.

Such nobility cannot go unpunished. Leafing through a cookbook filled with impossible recipes, Conde finds a folded rotogravure photo from the 1950s of a gorgeous nightclub singer wrapped in gold lamé, Violeta del Rio. Conde falls in love not solely owing to her allure but because the photo awakens a dim memory and that nagging gut feeling that something is not right.

The magazine page leads Conde on the trail of a cold case murder dating back to the heydey of Havana nightlife. Batista gets the boot, sending his gangster business partners, along with rich Cubanos, in headlong flight with whatever dollars remain of their riches, leaving behind their mansions to fall into rot. One such Cubano, Alcides Montes de Oca, scion of a respected family de nombre, had fallen head over heels with the alluring Lady of the Night, bolero singer Violeta del Rio. The rich man flees in 1960, without Violeta del Rio. Because police have their hands full investigating counterrevolutionary terrorist violence, the singer’s death by cyanide remains an open case.

Montes de Oca leaves behind the fabulous library, the devastated mansion, and three caretakers, his dedicated personal assistant and her two children—Montes de Oca’s children carrying the surname of a chauffeur to keep up appearances. The novel follows Conde from sympathy for the emaciated brother and sister to suspicion that one of them withholds secrets to unlock the mysterious death of the almost forgotten singer. On the trail, the detective tracks down a musiciologist who identifies the single recording of Violeta del Rio, the singer’s top rival--a once-ravishing beauty now a sadly vain old woman holding in bitterness at her fifty year old feud, and another wizened body formerly known as Lotus Flower--a sensational nude dancer and high-class madam, who gladly shows off a portrait of her young self in costume.

The mystified Conde calls upon all his resources to resolve events the reader already knows from letters interjected into the narrative. Mysterious love letters by Nena to her Love parallel Conde’s investigation. Love is definitely Montes de Oca. Nena is not a character in the story and there’s some fun to be had in guessing her name. The letters allude to the events Conde has not yet tracked, filling in some details, offering misinformation here and there, but eventually spelling out the killer’s identity, and Nena’s. It’s a fun bit of dramatic irony, with added irony, Conde will never read the letters, the poisoner having destroyed them.

Beyond weaving an engaging mystery, crafting vivid tours of battered barrios, sentimental interviews that evoke that earlier hustle and bustle, Havana Fever reminds a reader of the inevitability of getting old. And its consequences. Conde has lost a step, in fact gets his ass kicked viciously because he loses focus. Conde’s best friend, Skinny Carlos, is killing himself with food, alcohol, and as much excess as a paraplegic shot in Angola can muster. Carlos deserves a happy ending, Conde reasons, and spends lavishly to bring rich food and quality rum to regular late night bullsessions.

Cuba is aging too, but not as well. The old are starving to death and when they’re gone, memories of the old days will be gone with them. While the old order changes it yields place to ever more bullshit, corruption, drugs. The gaps grow between then and now. And what can one do about it? Make compromises, survive, hold to your principles. They are their own reward. Or, one can leave, disappear from involvement in whatever comes next. Or, one can give in.

A final thought on publishing emerges in the British English of the translation. Cars have boots and bonnets, an envelope contains a pair of black and white winkle-pickers, and several colloquialisms drive my curiosity what Padura’s Spanish actually read. These linguistic lacunae aside, Peter Bush offers a masterful completely readable text that flows with a beautiful vocabulary and a clean sense of authenticity. Readers who have enjoyed Conde’s earlier stories, notably the Havana color series, Black, Red, Blue, and Gold novels, will find this story of the aging Conde a capstone to the series. In an afterword, Padura reveals he’s been working on movie versions of his work, and that is fabulous news. Read the books, read Havana Fever, and you can join those discussions one day, “it didn’t happen like that in the book, but…”

And that's the penultimate Tuesday in July, 2009, a Tuesday like any other Tuesday, except You Are Here. Thank you for visiting La Bloga.La Bloga welcomes your comments on this and all columns. Click the comments counter below to share your views. La Bloga welcomes guest columnists. If you have alternative views to this or another column, or a cultural/arts event to report, perhaps something from your writer's notebook, click here to discuss your invitation to be our guest.

Be sure to visit La Bloga this Sunday, July 26, when our Guest Columnists will be poets Olga Garcia, Tatiana de la Tierra, and making her writing debut, Liz Vega.

Michael Sedano

Roland Merullo. Fidel's Last Days. NY: Random House, 2009.

ISBN: 978-1-4159-6120-9 (1-4159-6120-4)

Imagine Fidel Castro lying on his death bed, holding onto life’s last breath with a stubbornness that infuriates those enemies who fervently wish Castro dead at the hands of an assassin, not the respite of natural causes. “Oye, pendejo,” Fidel might think--were he a bit of a Chicano--“if you want me killed, write a pinche novel, ‘cause it ain’t happening any other way.” Which is what Roland Merullo has done. Write a novel, Fidel’s Last Days.

Imagine Fidel Castro lying on his death bed, holding onto life’s last breath with a stubbornness that infuriates those enemies who fervently wish Castro dead at the hands of an assassin, not the respite of natural causes. “Oye, pendejo,” Fidel might think--were he a bit of a Chicano--“if you want me killed, write a pinche novel, ‘cause it ain’t happening any other way.” Which is what Roland Merullo has done. Write a novel, Fidel’s Last Days.

Palestine Poster designed by Faustino Perez in 1968

Hop on over to So Much Pileup. There showing OSPAAAL posters all week.

No Tags©2008 Grain Edit

The Surrender Tree (Henry Holt & Company)ISBN: 9780805086744Hardcover: 169 p. List Price: $16.95**** (4 out of 5 stars: very good; without serious flaws; highly recommended)Slavery all day,and then, suddenly, by nightfall – freedom!*Can it

Add a Comment

Wonderful post.

LikeLike

Absolutely stunning!

LikeLike

Great pics! They’re stunning photos!

LikeLike

Thanks! That was a nice armchair-trip!

LikeLike

The last photo is my favorite! :)

LikeLike

Krista, The words used to describe each photo made them even more sensitive and communicative. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your kind words have made my day. I’m humbled. Thank you!

LikeLike

I’m fond of that photo too. I can’t help but wonder why he’s smiling. Such a lovely portrait.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing my picture :)

LikeLike

You’re welcome Rob — I really enjoyed visiting your site.

LikeLike