new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: English language, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 27

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: English language in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Cassandra Gill,

on 10/9/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Politics,

Language,

Social Networking,

social media,

America,

oxford english dictionary,

enlightenment,

twitter,

Tweets,

english language,

*Featured,

presidential candidates,

american politics,

Online products,

digital technology,

public officials,

The Independent Reflector,

William Livingston,

Add a tag

A New Yorker once declared that “Twitter” had “struck Terror into a whole Hierarchy.” He had no computer, no cellphone, and no online social media following. He was not a presidential candidate, but he would go on to sign the Constitution of the United States. So who was he? And what did he mean by “Twitter”?

The post Twitter and the Enlightenment in early America appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Priscilla Yu,

on 10/3/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

science writing,

foreign language,

english language,

*Featured,

Science & Medicine,

Biocode,

Dawn Field,

The Double Helix with Dawn Field,

The New Age of Genomics,

language barrier,

language translation,

language-learning platform,

lingua franca,

scientific English,

Add a tag

Even when speakers are proficient in English, Scientific English can still present challenges. Some bill it as ‘a foreign language’ even for native English speakers. Anyone who has learned how to use it might first laugh at that comparison and then grit their teeth on the grain of truth. Learning conversational English is a big enough task. Getting good enough to build a career in science fluently using Scientific English is a Herculean task.

The post Hey, language-learning platforms! appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Franca Driessen,

on 9/18/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

grammar,

Philosophy,

linguistics,

english language,

*Featured,

paradoxes,

yablo paradox,

Arts & Humanities,

Roy T. Cook,

Paradoxes and Puzzles with Roy T. Cook,

paradoxes and puzzles with Roy T Cook,

periphrastic,

Add a tag

Let us say that a sentence is periphrastic if and only if there is a single word in that sentence such that we can remove the word and the result (i) is grammatical, and (ii) has the same truth value as the original sentence.

The post Periphrastic puzzles appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Estefania Ospina,

on 8/17/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Holy Cross Day,

Newgate Street,

Nutting Day,

Books,

grammar,

Language,

folklore,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

english,

anatoly liberman,

Linguistics,

english language,

*Featured,

Anglo-Saxon word etymology,

Anatoly Liberman Column,

Add a tag

All words, especially kl-words, and no play will make anyone dull. The origin of popular sayings is an amusing area of linguistics, but, unlike the origin of words, it presupposes no technical knowledge. No grammar, no phonetics, no nothin’: just sit back and relax, as they say to those who fly overseas first class. So here is another timeout.

The post As black as what? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Catherine,

on 4/9/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

timeline,

english language,

*Featured,

oxford dictionaries,

English Words,

OxfordWords blog,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Quizzes & Polls,

history of words,

History,

Language,

Add a tag

Do you know when laugh entered the English language? What about cricket or fair-weather friend? Take the OED Timeline Challenge and find out if you are a lexical brainiac (1975). To play, simply drag the word to the date at which you think it entered the English language.

The post OED timeline challenge: Can you guess when these words entered the English language? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Paget,

on 2/4/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Arts & Humanities,

simon horobin,

How English Became English,

american education system,

Gwynne’s Grammar,

latin nouns,

teaching latin,

Books,

Literature,

Education,

grammar,

Language,

etymology,

Linguistics,

Latin,

english language,

teaching english,

webster,

*Featured,

Add a tag

English grammar has been closely bound up with that of Latin since the 16th century, when English first began to be taught in schools. Given that grammatical instruction prior to this had focused on Latin, it’s not surprising that teachers based their grammars of English on Latin. The title of John Hewes’ work of 1624 neatly encapsulates its desire to make English grammar conform to that of Latin.

The post How English became English – and not Latin appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 11/27/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

idioms,

mark peters,

curse words,

english language,

lexicon,

bullshit,

*Featured,

lexiography,

American Election,

Jag Bhalla,

etymology of curse words,

bullshit: a lexicon,

slang term for bullshit,

reduplicative words,

Add a tag

Terms for bullshit in the English language have grown so vast it has now become a lexicon itself. We talked to Mark Peters, author of Bullshit: A Lexicon, about where the next set of new terms will come from, why most of the words are farm related, and bullshit in politics.

The post What a load of BS: Q&A with Mark Peters appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 8/15/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

greek mythology,

punctuation,

Latin,

english language,

Achilles,

*Featured,

catullus,

ancient greek,

Classics & Archaeology,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

classical poetry,

Classical Latin,

Arts & Humanities,

OSEO classics,

the oxford comma,

Add a tag

Only Oscar Wilde could be quite so frivolous when describing a matter as grave as the punctuation of poetry, something that causes particular grief in our attempts to understand ancient texts. Their writers were not so obliging as to provide their poems with punctuation marks, nor to distinguish between capitals and small letters.

The post A comma in Catullus appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Helena Palmer,

on 6/8/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

israel,

Linguistics,

english language,

Languages,

language change,

gaelic,

Ancient Languages,

*Featured,

Irish Language,

A History of the Irish Language,

Aidan Doyle,

Dead Languages,

History of Linguistics,

Linguistics Change,

Morphology,

Native Languages,

Books,

Language,

english,

irish,

Hebrew,

Add a tag

In the literature on language death and language renewal, two cases come up again and again: Irish and Hebrew. Mention of the former language is usually attended by a whiff of disapproval. It was abandoned relatively recently by a majority of the Irish people in favour of English, and hence is quoted as an example of a people rejecting their heritage. Hebrew, on the other hand, is presented as a model of linguistic good behaviour: not only was it not rejected by its own people, it was even revived after being dead for more than two thousand years, and is now thriving.

The post Changing languages appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 6/15/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

book,

tree,

Language,

word origins,

oed,

etymology,

english language,

oxford dictionary,

runes,

Philip Durkin,

*Featured,

rune,

oxford words,

liber,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

whatisabook,

Borrowed Words,

‘beech’,

durkin,

‘book’,

book’,

beech,

Add a tag

By Philip Durkin

The obvious answer to ‘when is a book a tree?’ is ‘before it’s been made into a book’ – it doesn’t take a scientist to know that (most) paper comes from trees – but things get more complex when we turn our attention to etymology.

The word book itself has changed very little over the centuries. In Old English it had the form bōc, and it is of Germanic origin, related to for example Dutch boek, German Buch, or Gothic bōka. The meaning has remained fairly steady too: in Old English a bōc was a volume consisting of a series of written and/or illustrated pages bound together for ease of reading, or the text that was written in such a volume, or a blank notebook, or sometimes another sort of written document, such as a charter.

The argument for…

The pages of books in Anglo-Saxon times were made out of parchment (i.e. animal skin), not paper. But nonetheless a long-standing and still widely accepted etymology assumes that the Germanic base of book is related ultimately to the name of the beech tree. Explanations of the semantic connection have varied considerably. At one point, scholars generally focused on the practice of scratching runes (the early Germanic writing system) onto strips of wood, but more recent accounts have placed emphasis instead on the use of wooden writing tablets.

Words in other languages have followed this semantic development from ‘material for writing on’ to ‘writing, book’. One example is classical Latin liber meaning ‘book’ (which is the root of library). This is believed to have originally been a use of liber meaning ‘bark’, the bark of trees having, according to Roman tradition, been used in early times as a writing material. Compare also Sanskrit bhūrjá- (as masculine noun) ‘birch tree’, and (as feminine noun) ‘birch bark used for writing’.

The argument against…

This explanation has troubled some scholars. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, the words for ‘book’ and ‘beech’ in the earliest recorded stages of various Germanic languages belong to different stem classes (which determine how they form their endings for grammatical case and number), and the word for ‘book’ shows a stem class that is often assumed to be more archaic than that shown by the word for ‘beech’.

Secondly, in Gothic (the language of the ancient Goths, preserved in important early manuscripts) bōka in the singular (usually) means ‘letter (of the alphabet)’. In the plural, Gothic bōkōs does also mean ‘(legal) document, book’, but some have argued that this reflects a later development, modelled on ancient Greek γράμμα (gramma) ‘letter, written mark’, also in the plural γράμματα (grammata) ‘letters, literature’ (this word ultimately gives modern English grammar), and also on classical Latin littera ‘letter of the alphabet, short piece of writing’, also in the plural litterae ‘document, text, book’ (this word ultimately gives modern English literature).

In light of these factors, some have suggested that book and its Germanic relatives may show a different origin, from the same Indo-European base as Sanskrit bhāga- ‘portion, lot, possession’ and Avestan baga ‘portion, lot, luck’. The hypothesis is that a word of this origin came to be used in Germanic for a piece of wood with runes (or a single rune) inscribed on it, used to cast lots (a practice described by the ancient historian Tacitus), then for the runic characters themselves, and hence for Greek and Latin letters, and eventually for texts and books containing these.

However, many scholars remain convinced that book and beech are ultimately related, and argue that the forms and meanings shown in the earliest written documents in the various Germanic languages already reflect the results of a long process of development in word form and meaning, which has obscured the original relationship between the word book and the name of the tree. For some more detail on this, and for references to some of the main discussions of the etymology of book, see the etymology section of the entry for book in OED Online.

This article first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Philip Durkin is Deputy Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, and the author of Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English.

Language matters. At Oxford Dictionaries, we are committed to bringing you the benefit of our language expertise to help you connect with your world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post When is a book a tree? appeared first on OUPblog.

Spell It Out: The Curious, Enthralling and Extraordinary Story of English Spelling David Crystal

Spell It Out: The Curious, Enthralling and Extraordinary Story of English Spelling David Crystal

Much like he does in The Story of English in 100 Words, Crystal has made language history exceedingly accessible. This is a basic history of English spelling and how it developed over time, and why it’s so darn wacky. (Short story-- trying to use the latin alphabet for a non-Latin language, scribes changing spelling to make things easier/prettier on the page, French influence after the Norman conquest, and the Great Vowel shift.)

But, for a book that could easily be boring, short chapters and a conversational style make this one an easy read. I also love love love love that Crystal doesn’t decry texting and the internet as ruining spelling. He also makes wonderful arguments as to why spelling is more important than ever. There's also an entire section for early education teachers with his ideas about how to teach spelling to make it more relevant, easier, and fun.

Very fun, and an Outstanding Book for the College Bound that I think teens will really enjoy.

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

By:

Sue Morris,

on 3/28/2014

Blog:

Kid Lit Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Children's Books,

Picture Book,

NonFiction,

Favorites,

children's book reviews,

English language,

sentence structure,

Vanita Oelschlager,

Library Donated Books,

vanita books,

language arts for kids,

6 Stars TOP BOOK,

Top 10 of 2014,

dangling participles,

Mike DeSantis,

Add a tag

.

.

Don’t Dangle Your Participle

by Vanita Oelschlager & Mike DeSantis, illustrator

Vanita Books 5/01/2014

978-1-938164-02-6

Age 4 to 8 24 pages

.

“Words and pictures show children what a dangling participle is all about. Young readers are shown an incorrect sentence that has in it a dangling participle. They are then taught how to make the sentence read correctly. It is done in a cute and humorous way. The dangling participle loses its way and the children learn how to help it find its way back to the correct spot in the sentence. This is followed by some comical examples of sentences with dangling participles and their funny illustrations, followed by an illustration of the corrected sentence. Young readers will have fun recognizing this problem in sentence construction and learning how to fix it.”

Opening

“What on earth is a participle and how does it dangle? Okay. Okay. Let’s start from the beginning.”

Review

In Don’t Dangle Your Participle Vanita explains what a dangling participle is and explains how to fix the sentence so that the participle no longer dangles and mangles the sentence’s meaning. The participle comes before the noun to clarify it, but Vanita shows how easy it is for the modifier to get lost, ending up in the wrong place in the sentence. If you still don’t get it from that explanation, well, this is because explanations are easier to understand when Vanita adds in pictures to make her point.

And it works!

I know this because dangling participles (and dangling modifiers, but that is another story) have always confused me, BUT honest, after reading Don’t Dangle Your Participle, I understand what a dangling participle is and how to correct the sentence and send the raskly participle on its way to bother someone else’s sentence. Don’t Dangle Your Participle belongs in every school library and language arts classrooms. Using humorous illustrations, Vanita shows how the participle, when left to dangle, changes the meaning of the sentences often with disastrous consequences. Try this one.

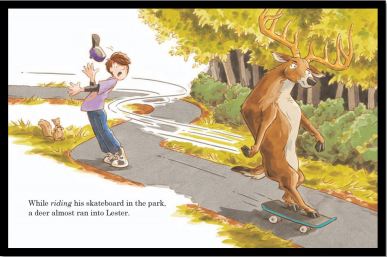

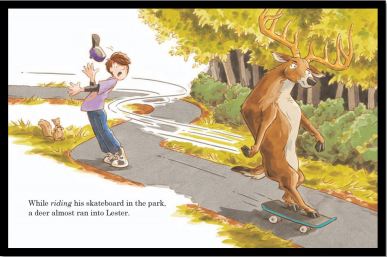

- While riding his skateboard in the park, a deer almost ran into Lester.

What this sentence is saying is this: When the deer rode his skateboard in the park, it almost ran into Lester. This is not what the sentence was supposed to mean. The dangling Participle—riding—changed the meaning of the sentence to something unintended and, as shown by the illustration, often something unintentionally funny. Vanita clearly shows kids how to fix these sentences.

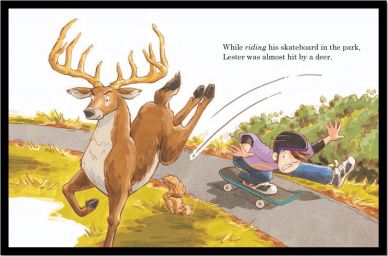

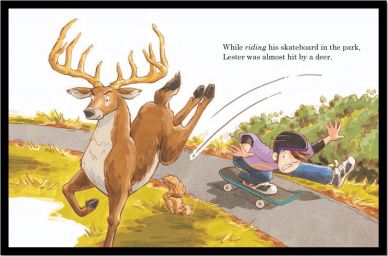

Did you get the correct sentence? Maybe another illustration will help.

Correct: While riding his skateboard in the park, Lester was almost hit by a deer.

Vanita has a canny way of helping kids understand English and its many rules. She effectively uses humor, which can help a child remember a concept. The more senses involved in learning, the better the material will be remembered. Vanita easily explains a subject, breaking it down so that kids can get the concept quickly. Don’t Dangle Your Participle may be her best language arts book yet.

Don’t Dangle Your Participle can help teachers explain sentence structure in general and the dangling participle. Many of Vanita’s books make great adjunct texts, especially in a homeschooling situation. For those kids that like to learn, Vanita Books make learning loads of fun. Don’t Dangle Your Participle helps the teacher and student, and charitable organizations—all net profits go to select charities. Try one more. Are you ready?

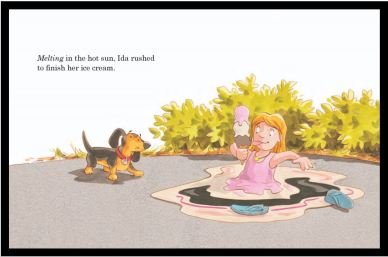

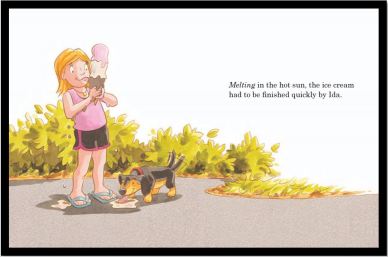

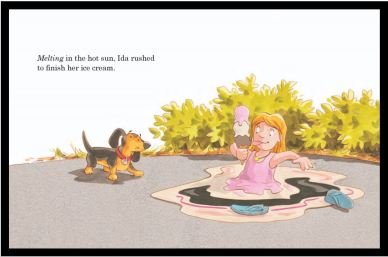

- Melting in the hot sun, Ida rushed to finish her ice cream.

This sentence says, As Ida was melting, she rushed to finish her ice cream. The dangling participle—melting—changed the meaning of this sentence. The writer is trying to say, the ice cream was melting, but darn it, he dangled the participle!

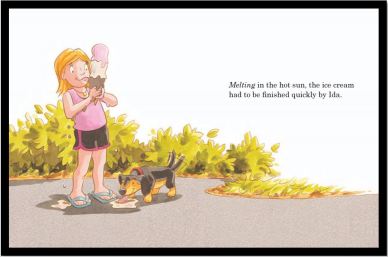

I bet you figured out the correct sentence. Just in case, here it is with a visual aide.

Correct: Melting in the hot sun, the ice cream had to be finished quickly

English is a difficult language. The rules are numerous and onerous. Kids need all the help they can get in understanding how to write English. Don’t Dangle Your Participle can be that help and should be available to every school child by way of the classroom and the library. Vanita explains the participle—a verb that acts like an adjective—and what happens when the participle no longer comes before the proper noun—it dangles. Her use of fun and funny illustrations help drive home her explanations. If I can finally understand these dangerous dangling participles, kids will be able to and probably faster. Use Don’t Dangle Your Participle can be used at home and at school to increase your child’s ability to write English properly. A skill that will help children their entire life.

.

Learn more about Don’t Dangle Your Participle HERE.

Buy Don’t Dangle Your Participle at Amazon—B&N—Vanita Books—your local bookstore.

.

Meet the author, Vanita Oelschlager at her website: http://vanitabooks.com/MeetVanita.html

Meet the illustrator, Mike DeSantis at his website: http://www.mikedesantis.com/picblog/

Find more wonderful Vanita Books at the publisher’s website: http://vanitabooks.com/index.html

.

DON’T DANGLE YOUR PARTICIPLE. Text copyright © 2014 by Vanita Oelschlager. Illustrations copyright © 014 by Mike DeSantis. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Vanita Books, Akron, OH.

. ALSO BY VANITA BOOKS

The Pullman Porter

Knees

Farfalla

Ariel Bradley

Magic Words

.

.

Reviews: The Pullmn Porter–Knees–Farfalla–Ariel Bradley–Magic Words

Filed under:

6 Stars TOP BOOK,

Children's Books,

Favorites,

Library Donated Books,

NonFiction,

Picture Book,

Top 10 of 2014 Tagged:

children's book reviews,

dangling participles,

English language,

language arts for kids,

Mike DeSantis,

sentence structure,

vanita books,

Vanita Oelschlager

Among the many sweet things that happened to me during

my trip south last week was Bill Bryson's

Mother Tongue: English and How it Got That Way. I'd found the book at my favorite used bookstore near the Penn campus a week before. I'd tucked it into my bag last minute. It kept me all kinds of company in airport lounges and sleepless stretches. It became my very dear friend.

Published in 1990, superceded, but of course, by newfangled research,

Mother Tongue still felt fresh to me, unencrusted. Where did our compunction to speak come from? Why is English so pervasive, and so challenging? What is good English and what is bad? And where do words actually come from?

The facts, the trends, the particulars are frankly delightful. Especially to one such as me, who—out of boredom, lack of proper education, corroded memory, or (let's be honest) poor eyesight—can't seem to stop herself from stretching language in every conceivable direction.

Here is a bit of trivia that I'm sure Bryson hunted down just for me: "Shakespeare used 17, 677 words in his writings, of which at least one tenth had never been used before. Imagine if every tenth word you wrote were original."

Love that? I love it.

Among Shakespeare's contributions, according to Bryson, were "barefaced, critical, leapfrog, monumental, castigate, majestic, obscene, frugal, radiance, dwindle, countless, submerged, excellent, fretful, gust, hint, hurry, lonely, summit, pedant, and 1685 others."

Where would we be without those words? What would I, personally, do without both

lonely and

hurry? And what can we do to keep our language alive?

It all makes me wonder, on this snowy St. Patty's Day: What word would you contribute to the English language, if you could?

By: Kirsty,

on 12/5/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

english language,

endangered languages,

Rick Perry,

American English,

Web of Language,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Michelle Bachmann,

CEPI,

english speakers,

Čepi,

US,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

There are roughly 7,000 languages spoken around the globe today. Five hundred years ago there were twice as many, but the rate of language death is accelerating. With languages disappearing at the rate of one every two weeks, in ninety years half of today’s languages will be gone.

Mostly it’s the little languages, those with very few speakers, that are dying out, but language death can hit big languages as well as little and mid-sized ones. And it can hit those big languages pretty hard. Sure, languages like Degere and Vuna are disappearing in Kenya, Jeju in Korea, Manchu in China. And sure, Nigerians complain that Yoruba is fast giving way to English. But language-watchers warn that English itself may have entered a steep and potentially irreversible decline in both its native and its adoptive country.

English, having spread as a global language during the 20th century, has now become so thin on the ground back home that it’s in danger of disappearing. That’s the conclusion of a new report which sees both competition from other languages and the increased ineptitude of English speakers combining to produce a catastrophic decline in the number of English speakers in England, the language’s ancestral home, as well as in the United States, where English speakers fled in search of religious liberty and alternate side of the street parking.

The report of the Center for the Study of English in the Public Interest, or ČEPI, available on that organization’s website, warns that the language could disappear in less than three generations, or perhaps they meant to say fewer? “Why should little languages like Frisian, Kashubian, and Han get all the attention?” the report asks. “Don’t the bleeding-heart anthropologists bent on preventing the inevitable realize that people stop speaking those doomed languages because other languages do the job better?” it adds. The report calls on those intent on saving endangered languages to switch their attentions to English, a language that might actually benefit from their efforts.

There’s good reason to preserve English rather than let it die. According to ČEPI director Bill Caxton, “When the last speakers go, they take with them their history and culture too.” Granted, Eskimo may not have twenty-three words for snow, as the popular myth would have it, but Eskimos do have a special relationship with snow, as evidenced by Eskimo idioms for ’snow clumped in the paws of sled dogs’ and ’snow outside the igloo that turns yellow when Morris is around.’ When Eskimo dies out, as it eventually must, that special relationship will be lost forever, and the Eskimos and the rest of the world will be left with the terms snow, slush, sleet, and snow covered with a crust of blackened automobile exhaust, hardly a vocabulary of nuance and poetry.

With the death of English, the ČEPI report notes, we’ll lose its prolific set of terms for burgers: in addition to hamburger, there’s cheeseburger, bacon burger, bacon cheeseburger, bleu cheese burger (also, blue cheese burger), quarter pounder, quarter pounder with cheese, swissburger, curry burger, tuna burger, turkey burger, chiliburger, soyburger, tofu burger, and black bean burger. And don’t forget hamburger not cooked long enough to eliminate e. coli. The wholesale loss of these terms testifying to English speakers’ preoccupation with chopped meat, and chopped meat substitutes, would be tragic.

When languages die, we also lose their secret herbal remedies and medicinal cures that could revolutionize modern medicine, their old family recipes that could turn the Food Channel on its ear. An English speaker discovered penicillin from traditional English bread mold (or mould), not to mention the extensive

By: Kirsty,

on 11/16/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

language,

Oxford Etymologist,

suitor,

etymology,

sugar,

anatoly liberman,

english language,

Romance language,

sure,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

english spelling,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The spelling of those two words does not bother us only because both are so common and learned early in life. Yet why not shure and shugar? There is a parallel case, and it too leaves us indifferent, though for a different reason. Consider su in pressure, measure, pleasure, leisure, and the like. We do not question the occurrence of su in the middle of a Romance word, with its phonetic value of sh (as in cushion) or ge (as in genre and rouge) and pay no attention to azure, in which the same sound is designated by a more natural group zu. The French origin of pressure, azure, measure, and their ilk, let alone genre and rouge, is so obvious that perhaps even those who have never studied French are dimly aware of it. By contrast, sure and sugar are fully domesticated (only etymologists know all the details of their descent), and, even more important, su in them occurs word initially. It is their position at the beginning rather than in the middle of the word that causes surprise. However, both sure and sugar also came to English from French and in this respect have common cause with pressure and measure.

From a historical point of view, the story is simple. Consider the names of the letters U and Q, that is (in phonetic terms), yu and kyu. Before y, t becomes ch, s turns into sh, and z yields the voiced partner of sh. Listen to how you say what you…; it is probably indistinguishable from watch you. Many (most?) people pronounce unless you as unlesh you, and I have seldom heard anyone pronounce the title of Shakespeare’s play As You Like It with z before you: it is usually the same sound as in Measure for Measure. In the middle of the word, rather than at word boundaries, an analogous assimilation happened several centuries ago, and that is why nature and vision sound as though they were spelled nachure and vizion. This brings us to sugar and sure.

The vowel occurring in French sure was alien to most Middle English dialects, including the dialect of London, and, as the name of the modern English letter U shows, yu replaced French u in borrowed words. We can observe this substitution even in such a recent loanword as menu (and compare nubile and other nu- words). Once sure appeared in English, it turned into syure, and a similar change happened in sugar (syugar). Later, syu- developed into sh- (compare bless you, session, and Asia, regardless of whether you have a voiced or a voiceless middle in the last of them, for the voicing is secondary). As noted above, sure and sugar are such conspicuous monsters because word initially su- designates sh only in those two words. (Actually, the plant name sumach also has a variant with shu-, but it is known too little. Sumach makes a good riddle: “There are three English words in which initial su- has the value of shu-. The first t

Mondegreen \MON-di-green\, noun:

Mondegreen \MON-di-green\, noun:

A word or phrase resulting from a misinterpretation of a word or phrase that has been heard.Timing can be a funny thing ... last week, I wrote about me and a friend misinterpreting the question, "How was the hike up?" for "How was the vodka?"

Mere days following that post, Dictionary.com sent MONDEGREEN as their Word of the Day.

So, as it turns out, "How was the vodka?" is a mondegreen. Did you already know of that word? Please ... be nice, and tell me you didn't.

I suspect mondegreens abound in the world of song lyrics. My personal favorite hails from a time before I could read. I had memorized many of the songs we sang regularly in church. There was one song, in particular, that included a phrase that stumped me every time we sang it. Nonetheless, I sang the words with all the confidence and vocal power I could muster, "P for Pine-sol, the highest good."

I remember being uncertain as to why we were singing about a cleaning product and how the church had picked Pine-sol as the best one. If I remember correctly, I even consulted with a dear friend. She agreed with the words, but didn't understand them either.

When I learned to read and decided to double-check the actual words ... imagine my surprise in learning that the phrase I had been singing, so often, as "P for Pine-sol, the highest good" was actually, "Be for my soul, the highest good." Ahhhh ... that made much more sense.

Think back ... do you have a favorite, funny mondegreen?

Say What?: The Weird and Mysterious Journey of the English Language Gena K. Gorrell

I was writing a really long review in my head as I read this book about the history of the English language. Mostly fascinating with some flaws. But then, reading the source notes, for a small pull-out box fact, she cites Wikipedia. That shut it down right there. If you can't find a better source than that, don't use the information. So not acceptable. The rest of the review and my feelings are moot. Nothing makes up for using Wikipedia as a source. NOTHING.

And now I'm just cranky.

Book Provided by... the publisher for Cybils consideration.

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

Everything in moderation, I say. I accept that random can be funny, but I almost hate the word now. Every social networking profile has a photo album originally entitled “randoms”. Sorry, typo from me there, I meant “randomz”. Now that that wrong has been wrighted (see what I did there?), I can go on and make my point.

Allow me to walk any reader through the scenario in question: the cringe inducing, shiver inspiring, hair-raising state of affairs that offends my very ears when I stumble upon it. One person, specimen A, sees object D in surroundings E. Object D is characteristically out of place in surroundings E. It may not seem it, but this is the ingenuity behind the humour that will inevitably ensue. Specimen A’s face lights up. He feverishly looks around to find a fellow conspirator. Specimen B is nowhere to be found, but he latches onto Specimen C. He reaches out for Specimen C, grasping his shoulder, delight blooming on his features. He takes a deep breath, languishing in the pleasure of his realisation of the misplacement of Object D in Surroundings E. Struggling for breath, fighting off a huge influx of serotonin flooding his brain, he starts to point. The next words leave scope for heightening the geekism. The following phrase, often too horrible to even utter, is uttered: “Zomg”, he says. Or, in an equivalent manoeuvre marginally less horrific, “Oh my god,” he says. Gasping in his next breath of air, he continues ,“that is so…”. Take note, at this point, that the ellipses are not there to make space to allow me to make my next point. It is representative of the length of the phrase “so” in the previous sentence. As Specimen A’s voice reaches a crescendo, he says it. He crosses the threshold and savours every syllable. “Random”. The horror. The word is said with completely indescribable pleasure, unsurpassed by any orgasm or drug.

In saying, “That is soooooooo random!”, specimen A descends into laughter that may be matched by specimen C. However, if specimen C has any presence of mind, he is fully within his rights to walk on, disgust or even indifference evident on his face. “Oh my god, that is so random”, pointing at a pickle on a sand dune or something, should not be someone’s sole basis for humour.

Posted on 8/2/2009

Blog:

Time Machine, Three Trips: Where Would You Go?

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

overuse of words,

English Language,

anecdote,

overuse of phrases,

humour,

miscellaneous,

Humor,

Satire,

Random,

Add a tag

Everything in moderation, I say. I accept that random can be funny, but I almost hate the word now. Every social networking profile has a photo album originally entitled “randoms”. Sorry, typo from me there, I meant “randomz”. Now that that wrong has been wrighted (see what I did there?), I can go on and make my point.

Allow me to walk any reader through the scenario in question: the cringe inducing, shiver inspiring, hair-raising state of affairs that offends my very ears when I stumble upon it. One person, specimen A, sees object D in surroundings E. Object D is characteristically out of place in surroundings E. It may not seem it, but this is the ingenuity behind the humour that will inevitably ensue. Specimen A’s face lights up. He feverishly looks around to find a fellow conspirator. Specimen B is nowhere to be found, but he latches onto Specimen C. He reaches out for Specimen C, grasping his shoulder, delight blooming on his features. He takes a deep breath, languishing in the pleasure of his realisation of the misplacement of Object D in Surroundings E. Struggling for breath, fighting off a huge influx of serotonin flooding his brain, he starts to point. The next words leave scope for heightening the geekism. The following phrase, often too horrible to even utter, is uttered: “Zomg”, he says. Or, in an equivalent manoeuvre marginally less horrific, “Oh my god,” he says. Gasping in his next breath of air, he continues ,“that is so…”. Take note, at this point, that the ellipses are not there to make space to allow me to make my next point. It is representative of the length of the phrase “so” in the previous sentence. As Specimen A’s voice reaches a crescendo, he says it. He crosses the threshold and savours every syllable. “Random”. The horror. The word is said with completely indescribable pleasure, unsurpassed by any orgasm or drug.

In saying, “That is soooooooo random!”, specimen A descends into laughter that may be matched by specimen C. However, if specimen C has any presence of mind, he is fully within his rights to walk on, disgust or even indifference evident on his face. “Oh my god, that is so random”, pointing at a pickle on a sand dune or something, should not be someone’s sole basis for humour.

HAMSTER HOLIDAYS: NOUN and ADJECTIVE ADVENTURES is here!!!

A troupe of hamsters celebrate a year of silly holidays in their unique hamster style. The book highlights nouns and adjectives on each page, as well as exploring opposites. Activity pages include scrambled words, match-up and crossword puzzles, and much more. Grammar becomes fun and games with hamster helpers.

HAMSTER HOLIDAYS--and all of the other books in the

PET GRAMMAR PARADE SERIES--are available in print format from these online bookstores:

Visit illustrator

KIT GRADY's web site for more information on the book's wonderful artist.

Special Education Teacher, Cathy Eshleman of Kearney, NB had this to say about the book:

Through the use of hamster antics, Cynthia Reeg, in her whimsical style, writes about nouns and adjectives in a way that will capture the interest of any student. Hamster Holidays: Noun and Adjective Adventures is a "must have" for any teacher who is introducing or reinforcing nouns or adjectives in the classroom.

Six children's authors will be sharing their books and answering questions this Wednesday. If you'd like to call in, here is the number: 646-649-1005.

If you'd like to find out more information and/or register for one of the more than 20 prizes to be given away in August, visit

Robin Falls Kids or email

[email protected]

This is the third of six blog talk programs this summer at Robin Falls Kids.

Don't miss it!

.jpg?picon=993)

By: Cynthia Reeg,

on 7/1/2009

Blog:

What's New

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

holidays,

picture books,

puzzles,

activities,

grammar,

eBooks,

Guardian Angel Publishing,

nouns,

Kit Grady,

adjectives,

study guide,

English language,

Hamster Holidays,

Add a tag

It's been a busy summer already. Just returned from an international trip--I'll share some photos later. But I didn't want to miss the opportunity to tell you the good news.

As you can see from the cover, illustrator

Kit Grady has brought to life these adorable and entertaining hamster characters in her own wonderful, colorful style.

You'll meet Grandpa and Babe, Carlos and Jenni, Billy--who's rather silly, and Lotty--who is decidedly spotty.

You can join them through a year of hare-brained holidays--sure to make you giggle. Nouns and adjectives are highlighted throughout the book. A study guide, activity sheet, and multiple puzzles are included.

One of the most distinctive characteristics of English is the number of words and phrases it has borrowed - and continues to borrow - from other languages, originally and most notably from Latin and French but now also from every corner of the globe. These words and phrases have been collected together to form From Bonbon to Cha-Cha: The Oxford Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases by Andrew Delahunty. But not all foreign-looking words are quite what they seem, as is explained by the excerpt below.

A number of words that look like foreign imports are not all that they seem. Some have been formed on the model of an existing foreign word and, while they have the appearance of a loanword, in fact have no equivalent in the supposed source language. Nom de plume is a good example. This term for ‘an assumed name used by a writer instead of their real name, a pen-name’ certainly looks French enough. But it was formed in English from French words in the early 19th century, based on the pattern of the genuinely French nom de guerre, ‘an assumed name under which a person engages in combat or some other activity or enterprise’. Similarly, bon viveur is a pseudo-French coinage, formed from the French words for ‘good’ and ‘living person’ to match the earlier imported phrase bon vivant. The Italian-sounding braggadocio, denoting boastful or arrogant behaviour, was originally the name Edmund Spenser gave to a boastful character in his poem The Faerie Queene. The ending is based on the authentically Italian suffix -occio (suggesting something large of its kind); the first part comes from the English brag or braggart.

Sometimes a foreign word can act as a template for other, often humorous, coinages. Literati, from Latin, dates from the 17th century and refers to well-educated people who are interested in literature. Their modern descendants include the glitterati (fashionable people or celebrities), the chatterati (another term for the chattering classes, intellectual or artistic people who express liberal opinions), and the digerati (computing experts regarded as a class). Sitzkrieg, formed on the analogy of blitzkrieg (literally ‘a lightning war’), was used in English in the 1940s to convey the idea of ‘a sit-down war’, a war, or a phase of a war, in which there is little or no active warfare. The Russian and Yiddish suffix -nik (as in words like Sputnik and kibbutznik) has been used, particularly since the 1950s, to form English words denoting a person associated with a specified thing or quality, such as refusenik, peacenik, beatnik, and no-goodnik.

Sometimes a foreign word can act as a template for other, often humorous, coinages. Literati, from Latin, dates from the 17th century and refers to well-educated people who are interested in literature. Their modern descendants include the glitterati (fashionable people or celebrities), the chatterati (another term for the chattering classes, intellectual or artistic people who express liberal opinions), and the digerati (computing experts regarded as a class). Sitzkrieg, formed on the analogy of blitzkrieg (literally ‘a lightning war’), was used in English in the 1940s to convey the idea of ‘a sit-down war’, a war, or a phase of a war, in which there is little or no active warfare. The Russian and Yiddish suffix -nik (as in words like Sputnik and kibbutznik) has been used, particularly since the 1950s, to form English words denoting a person associated with a specified thing or quality, such as refusenik, peacenik, beatnik, and no-goodnik.

El is the Spanish definite article, the equivalent of English the, as in El Dorado and El Greco. In the 20th century it has been used in English not only in titles such as El Supremo, but also in colloquial expressions as el cheapo. First recorded in the 1960s, this means ‘very cheap, of poor quality’, the English adjective cheap made to resemble a Spanish word by the addition of an o. The Costa Brava and Costa del Sol have inspired other pseudo-Spanish names of resort areas such as the Costa Geriatrica, describing one largely frequented or inhabited by elderly people.

By: Megan,

on 6/9/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

Reference,

language,

A-Featured,

slang,

English,

Adams,

english language,

jargon,

Michael,

Michael Adams,

Peoples,

Add a tag

Megan Branch, Intern

What do you think of when you think of slang? Maybe you think of a bunch of teenagers running around saying “OMG, like, LOL.” The truth is that everyone, not just young people, use slang –sometimes without even realizing it. In his new book, Slang: The People’s Poetry, Michael Adams suggests that our use of slang “outlines social space” and that “attitudes about slang partly construct group identity and identify individuals as members of groups”.

Adams, English language professor at Indiana University and author of several books on slang, writes that in addition to allowing slang users to be accepted into certain social groups, slang also acts as a barrier to keep those who aren’t “in the know” out. This is why someone over fifty may have trouble understanding the slang words of the under-twenty set. Below is a list , taken from Slang, of the top 10 slang words that are so hip they don’t even sound like slang.

1. Morning glory More than a flower, this slang term has existed since the early 1900s and has meant “something which or someone who fails to maintain an early promise” as well as, in the 1950s, “the first narcotic injection of the day.”

2. Gone Borneo This absurd-sounding phrase had a fairly short lifespan of about 10 years and was used in the 1980s to mean “intoxicated”.

3. Flash Still in use today, flash was used at least as far back as Charles Dicken’s Oliver Twist to mean “hip”.

4. Suck Although many people want this word to originate somewhere far more off-color, suck is simply a shortening of the phrases “suck eggs,” “suck rope,” and “suck wind”—all of which can be used to mean “disappointing.”

5. Wig It sounds like a hairpiece, but wig is the clipped form of “wig out,” a less widely-used synonym for “freak out.”

6. Duck A pretty, but “snob[by], stuck-up young woman,” who often requires a lot of “lettuce ‘cash in bills’” to please.

7. Pegging Used at a dance, much to her embarrassment, by Jo in Louisa May Alcott’s novel, Little Women.

“’I suppose you are going to college soon? I see you pegging away at your books—no, I mean studying hard,’ and Jo blushed at the dreadful ‘pegging’ which had escaped her.”

8. Bad Used “to mean its opposite, as well as ‘stylish, sexy, wonderful, formidably skilled’”.

9. Snack From a dictionary of terms “supposedly used by the criminal element” published in 1698 or 1699. After stealing your possessions, the thieves would snack ” ’share, go halves’ on them.”

10. Trouble & Strife A Cockney rhyming slang term that originated in London’s East End, trouble and strife is used to mean ‘the wife.’

Ammon Shea recently spent a year of his life reading the OED from start to finish. Over the next few months he will be posting weekly blogs about the insights, gems, and thoughts on language that came from this experience. His book, Reading the OED, has been published by Perigee, so go check it out in your local bookstore. In the post below Ammon looks at how many words are in the English language.

I was contacted recently by a journalist who is writing a story about the claim that the size of the English language is feverishly approaching one million words. This claim has been promulgated with varying degrees of self-righteousness over the past few years by a fellow who seems to be armed with little more than a purported algorithm and an inflated sense of importance. The notion of ‘one million words of English’ has been debunked by others who are far more educated than I (Ben Zimmer, Jesse Sheidlower, Geoffrey Nunberg), so I’ll not waste time in addressing it, except to note that calling it clap-trap would be unfair to the clap.

Yet it does make me wonder – why is it that we are so often interested in putting a number on something as inherently unquantifiable as vocabulary? The journalist who was writing the story was an educated and interesting person, and seemed genuinely curious about the subject. I wish that I’d had better answers for her but I can think of few things about which I have less knowledge than how many words our language has, and how many of them I (or anyone else) might know. I might as well be asked to state how many memories a person has.

I don’t mean to imply that this is not an area that deserves serious study; it obviously does, and there is a great deal of research done by linguists on many types of language acquisition (the phrase ‘vocabulary size’ yields approximately 11,000 results on Google Scholar). But there are so many awkward examples of people trying to come up with a sure-fire measurement for things such as the exact size of an average person’s vocabulary, or the total number of words in a language; the one commonality in these attempts seems to be a marked disparity.

There appears to be a certain degree of difficulty in ascertaining what a word is, at least for purposes of counting (is set one word or hundreds, do regional variants count as additional words, are obsolete terms to be counted?). Similarly, there seems to be no easy way to judge what it means to say that someone ‘knows’ what a word means – do they have to be able to define it, to know how to spell it, or can they pull a Potter Stewart, and simply ‘know it when they see it’?

I was thinking of all this today as I rode my bicycle through New York City traffic, trying to decide whether the word what would be one word or many, and how I would define it if I were so queried. I accomplished nothing except to give myself a headache, a near miss with a large truck, and a resolve to leave the counting of words to professionals, who are smart enough to stay away from algorithms.

No ... this post is not about spoon addictions ... nor is it about the fact that, in my house, spoons are always the first to be cleared out of the utensil drawer. We often have to run a load of dishes just to replenish the spoon supply ... and the bowls ... but that's a whole other post.

I love Dictionary.com. Since I never made it through the entire dictionary (I did try, in my grade school days ... but only made it to the third page of the As!), I subscribe to its Word of the Day e-mails in the hopes of enlightening myself with lots of new and fascinating words ... not always words that can be used in picture books ... but informative nonetheless!

Like today's word ... thaumaturgy (THAW-muh-tuhr-jee) ... a noun meaning "The performance of miracles or magic." Who knew?!

Well ... maybe you knew that ... but I didn't.

And, yesterday's word ... I had no idea a word existed for the phenomena that always seems to happen when you're speaking to a large group of people ... you know, when you flip-flop the first sounds or letters of a pair of words in a sentence, and end up saying something that sounds like gibberish?!

It's called spoonerism (SPOO-nuh-riz-uhm), a noun that means "The transposition of usually initial sounds in a pair of words."

Please tell me I'm not the only person who was not aware there was an actual word for this affliction!

Apparently (I thought this was fascinating), it hails from the Rev. William Archibald Spooner, who was a very kind but nervous clergyman and educator who committed this little flip-flopping of sounds quite a bit ... enough to get a word placed in the dictionary as a result!

Some of his examples included ...

"We all know what it is to have a half-warmed fish ["half-formed wish"] inside us."

"It is kisstomary to cuss ["customary to kiss"] the bride."

So, thank you Dictionary.com, for enlightening me, once again, to all those words out there that I had no idea even existed! It certainly helps with the goal to "learn something new every day"!

View Next 1 Posts

Hee, hee--I like your friend agreeing with you about the Pine-Sol. So cute.

When I was younger, I totally got the chorus of Blinded By the Light wrong!

Here's a link to more funny song mistakes:

http://dionroy.wordpress.com/2009/02/14/excuse-me-while-i-kiss-that-guy/

I know there are other songs I messed up!

Oh, yes, so many. I can't think of any right now. I'm sure I will in the middle of the night. Then I'll shout, "Golly, that was a mondegreen!"

Yup, I have known about Mondegreens for a long time. Did you know how that name came about? It was misheard lyrics from a song. They were understood as:They have slain the Earl O'Murray

and Lady Mondegreen. when in fact they were They hae slain the Earl O'Murray and laid him on the green.

A friend of mine used to sing "Bald-headed woman" for the BeeGees "More than a woman" but my favourite was "Baking Carrot Biscuits.. every day!" You know.. that Bachman Turner Overdrive song... ;)

(Taking Care of Business)

this is a new word for me .. very cool to learn something :D

And, I twist up song lyrics all the time... I'm always amazed when I learn the REAL lyric. But, when I was little I sang Silent Night, "Sleep in heavenly peas". It was a cute image in my mind.. a little baby Jesus in a pea pod.

What a wonderful mondegreen! My favourite one is my son who sings, "Doodley-daze again!"

Yes - that's his interpretation of Michael Jackson singing, "My lonely days are gone!"

I LOVE that word! And no, I'd never heard it.

If you like mondegreens, you'd love the game Mad Gab. My youngest got it for Christmas and it's really fun.

Cute. The one that I remember from my kid days was singing, "and you come to me on a submarine, keep me warm in your love..." in Bee Gees' How Deep Is Your Love. (summer breeze)

My daughter sings, "I keep keep breathing" instead of "bleeding" in that pop song I don't remember. I didn't bother correcting her.

Love it. :)

Ha! P is for Pine-Sol. I love it.

In middle school, my friend, Kate, always mixed up song lyrics. She thought "Wake Me Up Before You Go Go" was "Wake Me Up in Nova Scotia." She confused "Oh What a Feelin' When We're Dancin' on the Ceiling" for "Oh What a Feelin' When We're Dancing in New Zealand." And my fave was the Go-Go's "Our Lips Are Sealed." She thought it was a song about a girl named "Honest Cecile."

Hilarious.

I love that word – how perfect! That’s a funny story about Pine-Sol. I'm sure I've made similar mistakes.

oh now that is just too cute! pine-sol, the cleaner of the devout.

i'd have to say i made the same mistake kelly did ;)

thanks for stopping by my place from POTW. :)

You made my day - That is hilarious!

I did not know the word! But these are hilarious when you hear them!

Oh my word Kelly! This is why I love reading your blog. Your topics always seem to personal to me!!

My husband and I talk about this all the time. How we thing a lyric in a song is something and it turns out to be something totally different.

I read Hilary's comment! What a hoot!

Thanks for making me chuckle! Love this topic!

Blinded by the light, wrapped up like a douche in the quarter of the night.

You CANNOT tell me that those aren't the real words. I'm pretty sure those guys changed the words later...

My youngest used to sing, "Bluuuue awning!" Until we finally told him it was "Whooooo are you?" (by The Who) But we didn't tell him till last year. (He's 18.)

And Kelly, I'll happily tell you I did not know the word Mondegreen. But it's my very favorite new word now.