new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 19 of 19

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Oxford Scholarly Editions Online in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Hannah Charters,

on 9/7/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Infographics,

Oxford Reference,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

Arts & Humanities,

Oxford Handbooks,

Illuminating Shakespeare,

Shakespeare 2016,

shakespeare 400,

performing Shakespeare,

Shakespeare and Performance,

shakespeare infographic,

Literature,

Add a tag

Fools, or jesters, would have been known by many of those in Shakespeare's contemporary audience, as they were often kept by the royal court, and some rich households, to act as entertainers. They were male, as were the actors, and would wear flamboyant clothing and carry a ‘bauble’ or carved stick, to use in their jokes.

The post Shakespeare’s clowns and fools [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Charters,

on 2/7/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

epic poetry,

Homer,

Ancient Rome,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

latin poetry,

Tacitus,

Arts & Humanities,

OSEO classics,

Latin literature,

latin history,

Patrick Finglass,

Hesperos,

Hesperos: Studies in Ancient Greek Poetry Presented to M. L. West on his Seventieth Birthday,

poetry history,

Sir Ronald Syme,

History in Ovid,

Quintilian,

Ennius,

Add a tag

History and poetry hardly seem obvious bed-fellows – a historian is tasked with discovering the truth about the past, whereas, as Aristotle said, ‘a poet’s job is to describe not what has happened, but the kind of thing that might’. But for the Romans, the connections between them were deep: historia . . . proxima poetis (‘history is closest to the poets’), as Quintilian remarked in the first century AD. What did he mean by that?

The post A history of the poetry of history appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Helena Palmer,

on 11/16/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

future of publishing,

Academic Books,

Vilfredo Pareto,

academic publishing,

*Featured,

Nick Bostrom,

Images & Slideshows,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

superintelligence,

transformative experience,

#ReadUP,

#UPWeek,

university press week,

#AcBookWeek,

Academic Book Week,

Academic Texts,

Laurie Paul,

Manual of Political Economy,

Michael Banner,

The Ethics of Everyday Life,

The future of Academia,

Books,

Add a tag

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week and Academic Book Week with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Following on from our list of academic books that changed the world, we're looking to the future and how our current publishing could change lives and attitudes in years to come.

The post 5 academic books that will shape the future appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Charters,

on 11/3/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Gordon Campbell,

House of Lords,

guy fawkes,

Guy Fawkes Night,

gunpowder plot,

York,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

latin poetry,

British,

bonfire night,

*Featured,

Online products,

Arts & Humanities,

17th Century Literature,

History,

Literature,

Add a tag

The conspirators in what we now know as the Gunpowder Plot failed in their aspiration to blow up the House of Lords on the occasion of the state opening of parliament in the hope of killing the King and a multitude of peers. Why do we continue to remember the plot? The bonfires no longer articulate anti-Roman Catholicism, though this attitude formally survived until 2013 in the prohibition against the monarch or the heir to the throne marrying a Catholic.

The post The literary fortunes of the Gunpowder Plot appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 10/24/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

shakespeare,

william shakespeare,

Henry V,

British,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Andrew Zurcher,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Illuminating Shakespeare,

Anything for a Quiet Life,

Battle of Agincourt,

historical revisionism,

John Webster,

thomas middleton,

Add a tag

Young Cressingham, one of the witty contrivers of Thomas Middleton's and John Webster's comedy Anything for a Quiet Life (1621), faces a financial problem. His father is wasting his inheritance, and his new stepmother – a misogynistic caricature of the wayward, wicked woman – has decided to seize the family's wealth into her own hands, disinheriting her husband's children.

The post “There is figures in all things”: Historical revisionism and the Battle of Agincourt appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Charters,

on 10/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

horace,

Virgil,

ovid,

Ancient Rome,

*Featured,

catullus,

Classics & Archaeology,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Quizzes & Polls,

Classical Latin,

latin poetry,

hannah charters,

Arts & Humanities,

OSEO classics,

Add a tag

The shadow of the Roman poets falls right across the entire western literary tradition: from Vergil’s Aeneid, about the fall of Troy, the wooden horse, and the founding of Rome; through the great love poets, Catullus, Propertius, and Tibullus; Ovid’s Metamorphoses, treasure-house of myth for the Renaissance and Shakespeare; to Horace’s Dulce et decorum est, echoing through the twentieth century. We all take it for granted … so now’s the time to check your working.

The post Can you get X out of X in our Latin poetry quiz? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Yasmin Coonjah,

on 8/15/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

greek mythology,

punctuation,

Latin,

english language,

Achilles,

*Featured,

catullus,

ancient greek,

Classics & Archaeology,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

classical poetry,

Classical Latin,

Arts & Humanities,

OSEO classics,

the oxford comma,

Add a tag

Only Oscar Wilde could be quite so frivolous when describing a matter as grave as the punctuation of poetry, something that causes particular grief in our attempts to understand ancient texts. Their writers were not so obliging as to provide their poems with punctuation marks, nor to distinguish between capitals and small letters.

The post A comma in Catullus appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/18/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

digital academic research,

digital data structures,

modern scholarship tools,

online academic archives,

online academic research,

online scholarship,

tools for academic research,

Technology,

Media,

Mark Dunn,

*Featured,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

digital scholarship,

Life at Oxford,

Add a tag

For over 100 years, Oxford University Press has been publishing scholarly editions of major works. Prominent scholars reviewed and delivered authoritative versions of authors’ work with notes on citations, textual variations, references, and commentary added line by line—from alternate titles for John Donne’s poetry to biographical information on recipients of Adam Smith’s correspondence.

The post Devising data structures for scholarly works appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Hannah Charters,

on 1/25/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Arts & Humanities,

Gerard Carruthers,

Scottish Bard,

scottish literature,

Music,

Literature,

robert burns,

Burns Night,

*Featured,

Add a tag

‘Oh, that this too, too solid flesh would melt,’ so wrote the other bard, Shakespeare.

Scotland’s bard, Robert Burns, has had a surfeit of biographical attention: upwards of three hundred biographical treatments, and as if many of these were not fanciful enough hundreds of novels, short stories, theatrical, television, and film treatments that often strain well beyond credulity.

Burns has been pursued beyond (or properly in) the grave in even more extreme ways. His remains have been disinterred twice, the second time so that his skull might be examined for the purposes of phrenology. In death he has been bothered again very recently in the run up to Scotland’s referendum in October 2014. Would Burns have been a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ voter, a Nationalist or a Unionist, was often posed and answered across media outlets.

This de-historicised Burns, someone who never actually had any kind of political vote in life, who had no access to nationalist, or indeed, unionist ideology, in the modern senses is nothing new. During World War I, the minute book of the Dumfries Volunteer Militia, in which Burns had enlisted in 1795 in the face of threatened French invasion, was rediscovered. It was published in 1919 by William Will of the London Burns Club with a rather emotional introduction claiming that the minute-book’s records showing Burns’s impeccable conduct as a militiaman was proof of the poet’s sound British patriotism and how he might be compared to the many brave British soldiers who had just taken on the Kaiser. In response, those who had been recently constructing a pacifist Burns spluttered with indignation. Wasn’t the Scottish Bard the man who had written ‘Why Shouldna Poor Folk Mowe [make love]’ during the 1790s:

When Princes and Prelates and het-headed zealots

All Europe hae set in a lowe [noisy turmoil]

The poor man lies down, nor envies a crown,

And comforts himself with a mowe.

This is an increasingly obscene song, an anti-war text saying, ‘a plague on all your houses’ (to paraphrase the other bard again): the poor should choose love, and not war – the latter being the result of much more shameful shenanigans by their supposed lords and masters.

Ironically enough in ‘To A Louse’, Burns wrote:

O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

It wad frae monie a blunder free us

An’ foolish notion

The problem is that Burns would be dizzy with the multifarious contradictoriness of it all if he could truly emerge from the grave and attempt to see himself as others have seen him. Ultimately, what we have with Burns is the man who may or may not have been Scotland’s greatest poet, but who is certainly Scotland’s greatest song-writer (with the production of twice as many songs as poems) — the nearest Scotland has, a bit cheesy though the comparison is, to Lennon and McCartney. These songs and poems express indeed many different ideas, moods, emotions, and characters. They sympathise with radically different viewpoints (for instance, Burns can write empathetically on occasion about both Mary Queen of Scots (Catholic Stuart tyrant) and the Covenanters (Calvinist fanatics, according to their respective detractors)). Burns’s work is both his living achievement and the real remains over which we ought to pore. In the end there is no real Burns, but instead a fictional one and the important fictions are of his making.

Image Credit: Scottish Highlands by Gustave Doré (1875). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The myth-eaten corpse of Robert Burns appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 11/20/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Bae,

Literature,

william shakespeare,

Word of the Year,

WOTY,

Shakespeare's sonnets,

*Featured,

alice northover,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Word of the Year 2014,

WOTY2014,

Add a tag

In continuation of our Word of the Year celebrations and the selection of bae for Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year shortlist, I’m presenting my annual butchering of Shakespeare (previous victims include MacBeth and Hamlet). Of the many terms of endearment the Bard used — from lambkin to mouse — babe was not among them. In the 16th century, babe (which Shakespeare used a great deal) referred to a baby rather than a loved one. So instead, let us see how Shakespeare would address his mistress if he courted her like Pharrell Williams.

My bae’s eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound.

I grant I never saw a goddess go:

My bae when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

When my bae swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her though I know she lies,

That she might think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue.

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed:

But wherefore says she not she is unjust?

And wherefore say not I that I am old?

O, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,

And age in love loves not to have years told.

Therefore I lie with her, and she with me,

And in our faults by lies we flattered be.

The little Love-god lying once asleep

Laid by his side his heart-inflaming brand,

Whilst many nymphs, that vowed chaste life to keep,

Came tripping by; but in her maiden hand

The fairest votary took up that fire,

Which many legions of true hearts had warmed,

And so the general of hot desire

Was, sleeping, by a virgin hand disarmed.

This brand she quenched in a cool well by,

Which from love’s fire took heat perpetual,

Growing a bath and healthful remedy

For men diseased; but I, my bae’s thrall,

Came there for cure, and this by that I prove:

Love’s fire heats water; water cools not love.

For the original sonnets, plus expert commentary and notes, visit Oxford Scholarly Editions Online: Sonnet 130, Sonnet 138, and Sonnet 154.

The post Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Bae’ sonnets appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 9/11/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

quiz,

Poetry,

cats,

muse,

poems,

robert herrick,

Humanities,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

lit,

Online products,

john gay,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

Quizzes & Polls,

Oxford online products,

literary quiz,

cat quiz,

christopher smart,

hannah charters,

philip sydney,

shackerley marmion,

Literature,

cat,

Add a tag

The final, quiet days of summer before the turning of the season and the chill of back-to-work autumn are a perfect time to slow down, turn off the electronics, and refresh the soul by reading poetry. On the other hand, what could be more fun than an internet quiz about cats?

We sat down with Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, and fired up the search, looking for cats stalking the pages of literature. We found some lovely stuff, and something more – a literary reflection of the cat’s unstoppable gambol up the social ladder: a mouser and rat-catcher in the seventeenth century, he springs up the stairs in the eighteenth century to become the plaything of smart young ladies and companion of literary lions such as Cowper, Dr Johnson, and Horace Walpole.

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Image credit: Cat with OSEO, © Oxford University Press. Do not re-use without permission.

The post Whose muse mews? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 4/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Literature,

British,

correspondence,

National Archives,

Arcadia,

sidney,

tunis,

*Featured,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Sir Philip Sidney,

A Defence of Poesy,

Astrophil and Stella,

Roger Kuin,

sidney’s,

kuin,

Add a tag

By Roger Kuin

What does Sir Philip Sidney’s correspondence teach us about the man and his world? You have to realise what letters were, what they were like, and what they were for.

Some of them were like our e-mails: brief and to the point, sent for a practical reason. They were usually carried and delivered by a person known to the sender; so sometimes they are an introduction to the bearer, sometimes it’s the bearer who will tell the really sensitive news (frustrating for us!). These can tell us something about people and their specific interactions.

Other letters are long and more like a personal form of news media — meant to inform the recipient (often Sidney himself) about what is happening in the world of politics (with which religion is often mixed; it’s a time of religious wars). These are precious as sources for our knowledge of what happened. Take the example of the Turkish conquest of Tunis in the summer of 1574. One of Sidney’s correspondents, Wolfgang Zündelin, was a professional political observer in Venice, where all the news in the Mediterranean went first. So there is a series of letters from him recounting this huge amphibious victory by the Ottoman Turks, led by a converted Italian and a cruel Albanian, over the city of Tunis and its port La Goletta, defended by a mixed force of Spaniards and Italians, with a wealth of detail.

Most of us were taught about Sidney as the author of brilliant if rueful love-sonnets and of a long prose romance (ancestor of the novel) called the Arcadia. It is intriguing to meet the young man in these letters, in which poetry is never discussed and in which politics and governance are the paramount topics. We tend to forget how young he was. At 17 he went abroad and lived through a massacre in Paris; from there he travelled through Europe for nearly three years, studying in Padua, being painted by Veronese in Venice, and meeting princes from the King of France to Emperor Maximilian in Vienna.

At 22 he was chosen to head a ceremonial embassy (combined with confidential intelligence-gathering) to the new Emperor Rudolf II, which he carried off with enormous aplomb. The Emperor himself, brought up in Spain and very stiff, was not terribly impressed, but everyone else was.

Most of us know that Sidney was eventually killed in the Netherlands by a Spanish musket-ball at the age of 31; here we see him trying to manage the key port of Flushing (ceded to the English in return for their help to the Dutch against Spain), frustrated by lack of funds and support from England, trying not to despair of the Queen and hoping not only to deal the Spaniards a blow but to do some glorious deed in the process.

At the end there are three urgent lines, a scrawl really, now almost illegible in the National Archives, of a young man dying of gangrene and scribbling in bed a note calling for a German doctor he knows. Heartbreaking.

We know so much about him: more than about almost any other Englishman of his time. And yet there is still much we have to guess at. Nowhere does he state his thoughts, for instance, about religion, such a burning subject in his age. Nor does he write about literature, except to ask a friend to go on singing his songs and to tell his brother he will soon receive his, Philip’s, “toyful book”. There are no letters (that we know of) to his sister Mary, the Countess of Pembroke, herself a major poet; none to his two best friends Fulke Greville and Edward Dyer.

He was serious and charming, intense and cheerful, dutiful and ambitious. He wanted to do something for his country. Above all, he was fascinated by the idea of governance, not a word we use a lot. But for him it was everywhere. How do you govern yourself, in the face of those rebellious subjects, your passions? How do you govern a family? How do you govern soldiers, always underpaid and apt to plunder the countryside? How do you govern a country, help its allies, keep its enemies at bay? They are subjects not altogether irrelevant today; and reading his correspondence gives us an idea of the way they were viewed by a brilliant young man a mere four centuries ago.

But of course, this is not enough, in Philip Sidney’s case. We read about Sidney because we read Sidney. This astonishing young man mentioned above, in eight short years, wrote (a) the first great treatise of literary criticism in English, A Defence of Poesy (also known as An Apology for Poetry); (b) the first major sonnet-sequence in English, Astrophil and Stella; and (c) the first (then-)modern prose romance in English, Arcadia – which exists in two versions, the “Old” Arcadia, complete, and his unfinished revision of it, the “New” Arcadia.

Roger Kuin is Professor of English Literature (emeritus) at York University, Toronto, Canada. He is the editor of The Correspondence of Sir Philip Sidney (now available on Oxford Scholarly Editions Online). He has written extensively about Sidney and about Anglo-Continental relations in the later sixteenth century; lately he has been working on heraldic funerals, beginning with the very grand one of Sidney himself. He has a blog, Old Men Explore, and can be found on Facebook.

A range of Sir Philip Sidney editions available to subscribers of Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. Oxford’s scholarly editions provide trustworthy, annotated texts of writing worth reading. Overseen by a prestigious editorial board, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online makes these editions available online for the first time.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Sir Philip Sidney, the Bolton portrait. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Getting to know Sir Philip Sidney appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/14/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

shakespeare,

quotations,

birthday,

editions,

hamlet,

othello,

romeo and juliet,

king lear,

Shakespeare's sonnets,

Humanities,

Julius Caesar,

infographic,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

oxford shakespeare,

richard II,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Quizzes & Polls,

Shakespeare 450 birthday,

interlinked,

Pericles,

Troilus and Cressida,

our shakespeare,

1564,

Add a tag

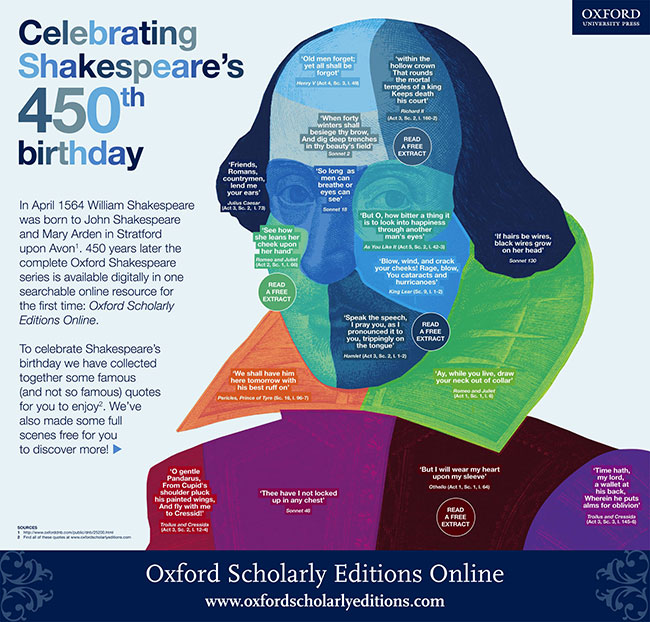

William Shakespeare was born 450 years ago this month, in April 1564, and to celebrate Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is testing your knowledge on Shakespeare quotes. Do you know your sonnets from your speeches? Find out…

William Shakespeare was born 450 years ago this month, in April 1564, and to celebrate Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is testing your knowledge on Shakespeare quotes. Do you know your sonnets from your speeches? Find out…

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Need a clue or two? Then take a look at our Shakespeare birthday infographic!

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major publishing initiative from Oxford University Press, providing an interlinked collection of authoritative Oxford editions of major works from the humanities, including the complete Oxford Shakespeare series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Droeshout portrait of William Shakespeare. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare’s 450th birthday quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/8/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

shakespeare,

editions,

graphic,

tour,

Humanities,

cornerstones,

infographic,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Images & Slideshows,

Arts & Leisure,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Shakespeare 450 birthday,

Shakespeare quotations,

interlinked,

sleeve,

Add a tag

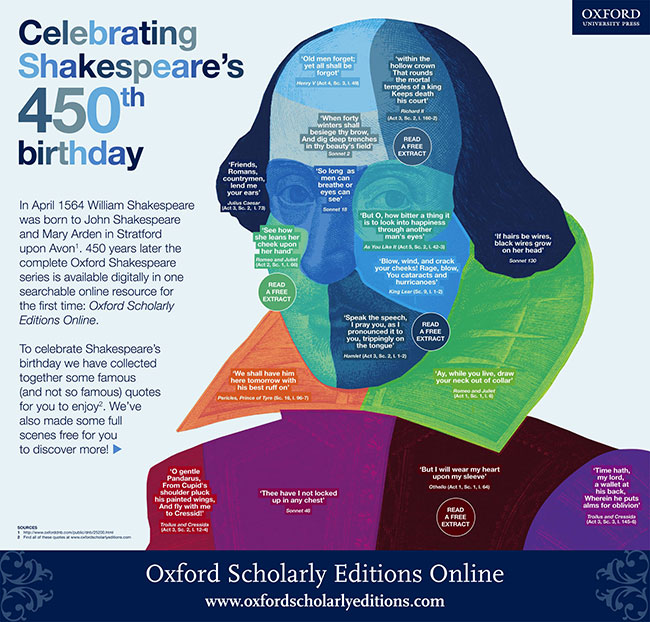

“But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve …”

– Othello (Act 1, Sc. 1, l.64)

April 2014 sees Shakespeare mature to the ripe old age of 450, and to celebrate we have collected a multitude of quotes from the famous bard in the below graphic, crafting his features with his own words.

To read the free scenes, open the graphic as a PDF.

Download the graphic as a jpg or PDF.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online provides an interlinked collection of authoritative Oxford editions of major works from the humanities. Scholarly editions are the cornerstones of humanities scholarship, and Oxford University Press’s list is unparalleled in breadth and quality. Read more about the site, follow the tour, or watch the full story.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Happy 450th birthday William Shakespeare! appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 3/28/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

women's history month,

francis bacon,

aphra behn,

Humanities,

*Featured,

katherine philips,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

83 song,

early modern women writers,

margaret cavendish,

mary wroth,

Oenone,

Oxford online products,

Add a tag

By Andrew Zurcher

As Women’s History Month draws to a close in the United Kingdom, it is a good moment to reflect on the history of women’s writing in Oxford’s scholarly editions. In particular, as one of the two editors responsible for early modern writers in the sprawling collections of Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO), I have been going through the edited texts of women writers included in the OSEO project, and thinking about how well even the most celebrated women writers from the period 1500 – 1700 are represented in this new digital format. In short, early modern English women writers have fared, perhaps predictably, badly.

The essayist, philosopher, and historian Francis Bacon has his place, in the Oxford Francis Bacon in fifteen volumes; but the philosopher and poet and essayist and dramatist and prose writer Margaret Cavendish, duchess of Newcastle, does not. Philip Sidney, famous for his pastoral poems, appeared in a stunningly erudite Oxford edition by William Ringler, Jr. in 1962, now like the Bacon edition a part of OSEO; Katherine Philips, also famous for her pastoral poetry, limps in to the Oxford fold in a 1905 text lightly edited by George Saintsbury, which also includes the minor Caroline poets Patrick Hannay, William Chamberlayne, and Edward Benlowes. Aphra Behn, one of the most prolific writers of the Restoration, hardly figures at all in OSEO, and the Oxford list does not include complete works for Isabella Whitney, Mary Herbert, Amelia Lanyer, or Mary Wroth.

Among those lyric poems and short works by women that are included in OSEO, many return to the silencing of a woman’s voice, the disabling of her love, and the banishment of her person. Typical is Mary Wroth’s “83 Song”, first published in Peter Davidson’s anthology, Poetry and Revolution: An Anthology of British and Irish Verse 1625-1660. Recognising that “the time is come to part” with her “deare”, the woman speaker of the poem gives up not only her own happiness, but his unhappiness. She goes to “woe”, while he goes to “more joy”:

Where still of mirth injoy thy fill,

One is enough to suffer ill:

My heart so well to sorrow us’d,

Can better be by new griefes bruis’d. (ll. 5-8)

The woman lover’s habituation to grief gives her a capacity for further bruising that, not without irony, she embraces as an ethical duty. Hers is a voice constructed for loss and for complaint, so much so that she cannot escape from this loss, and the woes that “charme” her, except by death – as the concluding stanza of the song suggests:

And yett when they their witchcrafts trye,

They only make me wish to dye:

But ere my faith in love they change,

In horrid darknesse will I range. (ll. 17-20)

For Wroth’s loving, jilted woman speaker, identity is constructed out of a wronged fidelity; the two options remaining to her are complaint and oblivion.

Complaint was still a powerful mode for women writers during the Restoration – certainly a mode that modern editors have much privileged in anthologies. A poem by Aphra Behn, “A Paraphrase on Oenone to Paris”, has slipped in to OSEO‘s corpus through its inclusion in John Kerrigan’s wonderful anthology, Motives of Woe: Shakespeare and ‘Female Complaint’: A Critical Anthology.

In this poem the shepherdess Oenone challenges the Trojan prince Paris, who had won her love while keeping flocks on the slopes of Mount Ida; afterward discovering his true birthright, Paris has abandoned her, and sails for Sparta, there to ravish Menelaus’ queen, Helen, and set in train the events that will lead to the Trojan War. Toward the end of Behn’s long poem of complaint, Oenone reprehends her lover for his faithlessness with an argument that seems to gesture at Behn’s own public reputation:

How much more happy are we Rural Maids,

Who know no other Palaces than Shades?

Who want no Titles to enslave the Croud,

Least they shou’d babble all our Crimes aloud;

No Arts our good to show, our Ills to hide,

Nor know to cover faults of Love with Pride.

I lov’d, and all Loves Dictates did persue,

And never thought it cou’d be Sin with you.

To Gods, and Men, I did my Love proclaim

For one soft hour with thee, my charming Swain,

Wou’d Recompence an Age to come of Shame,

Cou’d it as well but satisfie my Fame.

But oh! those tender hours are fled and lost,

And I no more of Fame, or Thee can boast!

‘Twas thou wert Honour, Glory, all to me:

Till Swains had learn’d the Vice of Perjury,

No yielding Maids were charg’d with Infamy.

‘Tis false and broken Vows make Love a Sin,

Hadst thou been true, We innocent had been. (ll. 265-83)

The “Titles” that Oenone disclaims are those of honour, the courtly ranks and degrees to which women might be raised by their paternity, or by their advantageous marriages; wanting titles, shepherdesses can sport in the shades of innocence, their sexual crimes unremarked and undisplayed. The shame and infamy that now await Oenone spring directly from Paris’ perjury, for the woman’s reputation for immodesty flows from the exposure accomplished by her jilting. To her way of thinking, a crime is no crime until it is published; this is a logic she has learned from men, who cover up their own crimes with “Pride”. But “Titles” may also be those of published books, and the “Arts” Oenone lacks may be just those powers of “Pride” that always enable men to abandon women – in a broad sense, the power to speak falsely. What women do, cries Behn’s Oenone, has been betrayed by what men say; what can a woman write, that will not collude in her own untitling?

Early modern women writers have not been much or widely published. There are many reasons, of course, for this history of omission and scant commission. But so long as we continue to anthologize selections from the works of women writers from this period, and to bundle them in mixed fardels, we collude in a history or pattern of dis-titling, of allowing early modern women poets to complain, but not to speak in their more diverse collected works. This pattern is changing: important new editions of Wroth and Behn have appeared in the last few decades, and – closer to home – the works of the translator and poet Lucy Hutchinson, in a meticulously edited text from David Norbrook and Reid Barbour, have recently joined the Oxford list and the OSEO fold. Other early modern women writers will surely follow. As Women’s History Month comes to an end, it’s high time we put a period to infamy, shame, oblivion, and bruising.

Andrew Zurcher is a Fellow and Director of Studies in English at Queens’ College, Cambridge, and a member of the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) editorial board.

Scholarly editions are the cornerstones of humanities scholarship, and Oxford University Press’s list is unparalleled in breadth and quality. Now available online, Oxford Scholarly Editions Online provides an interlinked collection of these authoritative editions. Discover more by taking a tour of the site.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Aphra Behn by Mary Beale. Image available on public domain via WikiCommons

The post Entitling early modern women writers appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/8/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

shakespeare,

Geography,

renaissance,

mars,

John Donne,

astrology,

astronomy,

marlowe,

place of the year,

Copernicus,

john evelyn,

galileo,

Humanities,

POTY,

Social Sciences,

Kepler,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Middleton,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

Place of the Year 2012,

poty 2012,

Claude Mylon,

Francois de Verdus,

Gascoigne,

Girolamo Preti,

John Skelton,

Marilyn Deegan,

Robert Burton,

Samuel Sorbière,

Thomas Hobbes,

Thomas Stanley,

William Lilly,

Literature,

Add a tag

By Marilyn Deegan

The new discoveries of the Mars rover Curiosity have greatly excited the world in the last few weeks, and speculation was rife about whether some evidence of life has been found. (In actuality, Curiosity discovered complex chemistry, including organic compounds, in a Martian soil analysis.)

Why the excitement? Well, astronomy, cosmology, astrology, and all matters to do with the stars, the planets, the universe, and space have always fascinated humankind. Scientists, astrologers, soothsayers, and ordinary people look up to the heavenly bodies and wonder what is up there, how far away, whether there is life out there, and what influence these bodies have upon our lives and our fortunes. Were we born under a lucky star? Will our horoscope this week reveal our future? What is the composition of the planets?

Astronomy is one of the oldest natural sciences, but it was the invention of the telescope in the early 17th century that advanced astronomy into a science in the modern sense of the word. Throughout the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and others challenged the established Ptolemeic cosmology, and put forth the theory of a heliocentric solar system. The Church found a heliocentric universe impossible to accept because medieval Christian cosmology placed earth at the centre of the universe with the Empyrean sphere or Paradise at the outer edge of the circle; in this model, the moral universe and the physical universe are inextricably linked. (This is a model that is typified in Dante’s Divine Comedy.)

Authors from John Skelton (1460-1529) to John Evelyn (1620-1706) lived in this same period of great change and discovery, and we find a great deal of evidence in Renaissance writings to show that the myths, legends, and scientific discoveries around astronomy were a significant source of inspiration.

The planets are of course not just planets: they are also personifications of the Greek and Roman gods; Mars is a warlike planet, named after the god of war. Because of its red colour the Babylonians saw it as an aggressive planet and had special ceremonies on a Tuesday (Mars’ day; mardi in French) to ward off its baleful influence. We find much evidence of the warlike nature of Mars in writers of the period: Thomas Stanley’s 1646 translation Love Triumphant from A Dialogue Written in Italian by Girolamo Preti (1582-1626) is a verbal battle between Venus and her accompanying personifications (Love, Beauty, Adonis) and Mars (who was one of her lovers) and his cohort concerning the superior powers of love and war. Venus wins out over the warlike Mars: a familiar image of the period.

John Lyly’s play The Woman in the Moon (c.1590-1595) also personifies the planets and plays on the traditional notion that there is a man in the moon. Lyly’s use of the planets is thought to reflect the Elizabethan penchant for horoscope casting. The warlike Mars versus Venus trope is common throughout the period, and it appears in the works of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Middleton, Gascoigne, and most of their contemporaries. A search in the current Oxford Scholarly Editions Online collection for Mars and Venus reveals almost 300 examples. Many writers of the period also refer to astrological predictions; Shakespeare in Sonnet 14 says:

Not from the stars do I my judgement pluck,

And yet methinks I have astronomy,

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;

This is thought to be a response to Philip Sidney’s quote in ‘Astrophil and Stella’ (26):

Who oft fore-judge my after-following race,

By only those two starres in Stella’s face.

Thomas Powell (1608-1660) suggests astrological allusions in his poem ‘Olor Iscanus’:

What Planet rul’d your birth? what wittie star?

That you so like in Souls as Bodies are!

…

Teach the Star-gazers, and delight their Eyes,

Being fixt a Constellation in the Skyes.

While there is still much myth and metaphor pertaining to heavenly bodies in 17th century literature, there is increasing scientific discussion of the positions of the planets and their motions. To give just a few examples, Robert Burton’s 1620 Anatomy of Melancholy discusses the new heliocentric theories of the planets and suggests that the period of revolution of Mars around the sun is around three years (in actuality it is two years).

In his Paradoxes and Problemes of 1633, John Donne in Probleme X discusses the relative distances of the planets from the earth and quotes Kepler:

Why Venus starre onely doth cast a Shadowe?

Is it because it is neerer the earth? But they whose profession it is to see that nothing bee donne in heaven without theyr consent (as Kepler sayes in himselfe of all Astrologers) have bidd Mercury to bee nearer.

The editor’s note suggests that Donne is following the Ptolemaic geocentric system rather than the recently proposed heliocentric system. In his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions of 1623 Donne castigates those who imagine that there are other peopled worlds, saying:

Men that inhere upon Nature only, are so far from thinking, that there is anything singular in this world, as that they will scarce thinke, that this world it selfe is singular, but that every Planet, and every Starre, is another world like this; They finde reason to conceive, not onely a pluralitie in every Species in the world, but a pluralitie of worlds;

There are also a number of letters written in the 1650s and 1660s between Thomas Hobbes and Claude Mylon, Francois de Verdus, and Samuel Sorbière concerning the geometry of planetary motion.

William Lilly’s chapter on Mars in his Christian Astrology (1647), is a blend of the scientific and the metaphoric. He is correct that Mars orbits the sun in around two years ‘one yeer 321 dayes, or thereabouts’, and he lists in great detail the attributes of Mars: the plants, sicknesses, qualities associated with the planet. And he states that among the other planets, Venus is his only friend.

There are few areas of knowledge where myth, metaphor, and science are as continuously connected as that pertaining to space and the universe. Our origins, our meaning systems, and our destinies — whatever our religious beliefs — are bound up with this unimaginably large emptiness, furnished with distant bodies that show us their lights, lights which may have been extinguished in actuality millenia ago. Only death is more mysterious, and many of our beliefs about life and death are also bound up with the mysteries of the universe. That is why we remain so fascinated with Mars.

Marilyn Deegan is Professor Emerita in the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College, University of London. She has published widely on textual editing and digital imaging. Her book publications include Digital Futures: Strategies for the Information Age (with Simon Tanner, 2002), Digital Preservation (edited volume, with Simon Tanner, 2006), Text Editing, Print and the Digital World (edited volume, with Kathryn Sutherland, 2008), and Transferred Illusions: Digital Technology and the Forms of Print (with Kathryn Sutherland, 2009). She is editor of the journal Literary and Linguistics Computing and has worked on numerous digitization projects in the arts and humanities. Read Marilyn’s blog post where she looks at the evolution of electronic publishing.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) is a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press. The launch content (as at September 2012) includes the complete text of more than 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, including all of Shakespeare’s plays and the poetry of John Donne, opening up exciting new possibilities for research and comparison. The collection is set to grow into a massive virtual library, ultimately including the entirety of Oxford’s distinguished list of authoritative scholarly editions.

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World – the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Written in the stars appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Nicola,

on 9/6/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Classics & Archaeology,

ben jonson,

Arts & Leisure,

digital strategy,

oxford scholarship,

scholarly editions,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

OSEO,

critical online editions,

online text,

sophie goldsworthy,

goldsworthy,

Literature,

publishing,

shakespeare,

Philosophy,

authority,

digitization,

digital publishing,

editions,

Oxford University Press,

sophie,

Humanities,

*Featured,

Add a tag

Today sees the launch of a major new publishing initiative from Oxford University Press: Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO). OSEO will provide trustworthy and reliable critical online editions of original works by some of the most important writers in the humanities, such as William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, as well as works from lesser-known writers such as Shackerley Marmion. OSEO is launching with over 170 scholarly editions of material written between 1485 and 1660, and annual content additions will cover chronological periods until it contains content from Ancient Greek and Latin texts through to the modern era. This is exciting stuff, and here Project Director Sophie Goldsworthy explains why!

By Sophie Goldsworthy

Anyone working in the humanities is well aware of the plethora of texts online. Search for the full text of one of Shakespeare’s plays on Google and you’ll find hundreds of thousands of results. Browse popular classics on Amazon, and you’ll find hundreds available for free download to your device in 60 seconds or less. But while we’re spoilt for choice in terms of availability, finding an authoritative text, and one which you can feel confident in citing or using in your teaching, has paradoxically never been more difficult. Texts aren’t set in stone, but have a tendency to shift over time, whether as the result of author revisitings, the editing and publishing processes through which they pass, deliberate bowdlerization, or inadvertent mistranscription. And with more and more data available online, it has never been more important to help scholars and students navigate to trusted primary sources on which they can rely for their research, teaching, and learning.

Oxford has a long tradition of publishing scholarly editions — something which still sits at the very heart of the programme — and a range and reach unmatched by any other publisher. Every edition is produced by a scholarly editor, or team, who have sifted the evidence for each: deciding which reading or version is best, and why, and then tracking textual variance between editions, as well as adding rich layers of interpretative annotation. So we started to re-imagine how these classic print editions would work in a digital environment, getting down to the disparate elements of each — the primary text, the critical apparatus, and the explanatory notes — to work out how, by teasing the content of each edition apart, we could bring them back together in a more meaningful way for the reader.

We decided that we needed to organize the content on the site along two axes: editions and works. Our research underlined the need to preserve this link with print, not only for scholars and students who may want to use the online version of a particular edition, but also for librarians keen to curate digital content alongside their existing print holdings. And yet we also wanted to put the texts themselves front and centre. So we have constructed the site in both ways. You can use it to navigate to a familiar edition, travelling to a particular page, and even downloading a PDF of the print page, so you can cite from OSEO with authority. But you can also see each author’s works in aggregate and move straight to an individual play, poem, or letter, or to a particular line number or scene. Our use of XML has allowed us to treat the different elements of each edition separately: the notes keep pace with the text, and different features can be toggled on and off. This also drives a very focused advanced search — you can search within stage directions or the recipients of letters, first lines or critical apparatus — all of which speeds your journey to the content genuinely of most use to you.

As a side benefit — a reaffirmation, if you like, of the way print and online are perfectly in step on the site — many of our older editions haven’t been in print for some time, but embarking on the data capture process has made it possible for us to make them available again through on-demand printing. These texts often date back to the 1900s and yet are still considered either the definitive edition of a writer’s work or valued as milestones in the history of textual editing, itself an object of study and interest. Thus reissuing these classic texts adds, perhaps in an unanticipated way, to the broader story of dissemination and accessibility which lies at the heart of what we are doing.

For those minded to embark on such major projects, OSEO underlines Oxford’s support for the continuing tradition of scholarly editing. Our investment in digital editions will increase their reach, securing their permanence in the online space and making them available to multiple users at the same time. There are real benefits brought by the size of the collection, the aggregation of content, intelligent cross-linking with other OUP content — facilitating genuine user journeys from and into related secondary criticism and reference materials — and the possibility of future links to external sites and other resources. We hope, too, that OSEO will help bring recent finds to an audience as swiftly as possible: new discoveries can simply be edited and dropped straight into the site.

Over the past century and more, Oxford has invested in the development of an unrivalled programme of scholarly editions across the humanities. Oxford Scholarly Editions Online takes these core, authoritative texts down from the library shelf, unlocks their features to make them fully accessible to all kinds of users, and makes them discoverable online.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sophie Goldsworthy is the Editorial Director for OUP’s Academic and Trade publishing in the UK, and Project Director for Oxford Scholarly Editions Online. To discover more about OSEO, view this series of videos about the launch of the project.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

By: ReaganK,

on 9/1/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

Multimedia,

chaucer,

Walter William Skeat,

Research Tools,

Canterbury Tales,

Humanities,

*Featured,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online Products,

Christopher Cannon,

Edith Rickert,

Ellesmere,

Jill Mann,

John Manly,

OSEO,

recension,

Riverside Chaucer,

rickert,

manly,

Add a tag

By Christopher Cannon

The editing of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the form in which we now read it took many decades of work by a number of different scholars, but there is as yet no readily available edition that takes account of all the different versions in which the Canterbury Tales survives. Some of this is purely pragmatic. There are over 80 surviving manuscripts from before 1500 containing all or some parts of the Tales (55 of these are complete texts or were meant to be). The great Oxford edition of the nineteenth century, by Walter William Skeat, relies mostly on a single manuscript (‘Ellesmere’) with corrections from only six other texts. The edition in which most people have read the Tales in recent decades, the Riverside Chaucer (also printed in the UK by Oxford), also relies on Ellesmere, although it consults many more manuscripts than six to establish its base text. This is also Jill Mann’s practice in the recent Penguin edition of the Tales. But what if someone wanted to edit Chaucer from all the manuscripts, accounting carefully for all the variations? What if a student simply wanted to get some sense of what sorts of variation were possible in a manuscript culture, where every copy of a text was different because every such copy had to be hand-written?

The editing of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in the form in which we now read it took many decades of work by a number of different scholars, but there is as yet no readily available edition that takes account of all the different versions in which the Canterbury Tales survives. Some of this is purely pragmatic. There are over 80 surviving manuscripts from before 1500 containing all or some parts of the Tales (55 of these are complete texts or were meant to be). The great Oxford edition of the nineteenth century, by Walter William Skeat, relies mostly on a single manuscript (‘Ellesmere’) with corrections from only six other texts. The edition in which most people have read the Tales in recent decades, the Riverside Chaucer (also printed in the UK by Oxford), also relies on Ellesmere, although it consults many more manuscripts than six to establish its base text. This is also Jill Mann’s practice in the recent Penguin edition of the Tales. But what if someone wanted to edit Chaucer from all the manuscripts, accounting carefully for all the variations? What if a student simply wanted to get some sense of what sorts of variation were possible in a manuscript culture, where every copy of a text was different because every such copy had to be hand-written?

Since 1940 such curiosity could be satisfied in John Manly and Edith Rickert’s seven-volume Text of the Canterbury Tales ‘on the basis of all the known manuscripts’. But this edition has been under a cloud ever since it first appeared because it used all these manuscripts to try to work back to the ‘original’ text of the Tales (the process is called ‘recension’), and accidentally demonstrated in the process that this is not possible. There probably never was such an original, not least because Chaucer never finished the Tales, and even if there had been, there are too many small errors in the extant manuscripts to eliminate all of them. A more practical obstacle for any curiosity about the nature of this variation, however, is the form in which Manly and Rickert had to present the information they assembled. Take just the 10th line of the portrait of the ‘clerk of Oxford’ in the General Prologue of the Tales, for example, in which the narrator tells us his library consisted of

Twenty bookes clad in black or reed

This line can be found on p. 14 of volume 3 of this edition, and if one looks down to the bottom of the page a set variants is displayed in this way:

or] and Ha4 –a –b* (-) cd* (-) Bo2 En3 Fi PS Py Ra3 Tc1

‘Or’ identifies the word for which variants exist; the close bracket marks the start of those variants; ‘and’ is the word that sometimes occurs instead of ‘or’; and the alphanumeric soup that follows ‘and’ consists of the identifiers (‘sigla’) for the manuscripts in which this variant can be found. As it happens, this list is a simplified account of the variants for this line in all of the manuscripts that Manly and Rickert consulted — what it seemed necessary to mention in order to justify the text they printed. The full variation of these variants is printed in the ‘corpus of variants’ that fills the last three volumes of this edition, and the entry for the line I have just quoted (on page 24 of volume 5) is as follows:

bookes] goode b. Ps2 | clad] clothed Ha4 Ii; clodde Ht | blak] whit Cx1 Fi N1 Py S12 Tc1 | or ] and a Bo2 c Cx1 D1 Fi En3 Ha2 Ha4 Ht Ii Ld1 Mg Mm N1 Ps Py ra3 Ry2 Se Tc1 | reed] in r. Dd Ht Ry1

This list shows that some manuscripts say ‘goode bookes’ rather than only ‘bookes’, that some say ‘clodde’ or ‘clothed’ rather than ‘clad’, and that some say ‘white’ rather than ‘black’. None of these differences is hugely consequential (though the last of them is certainly interesting), but the combination of triviality (to meaning) and complexity (of form) will itself be enough to explain why Manly and Rickert place them in separate volumes, or why an editor such as Skeat would narrow the range of manuscripts from which he chose his readings to 7, or why he too would limit the variants he printed to no more than the readings he corrected (few enough to fit in a narrow column at the bottom of each page). In fact, for the line on the clerk’s books, there is nothing at all at the foot of Skeat’s page, although the line printed is slightly different from Manly and Rickert’s:

Twenty bokes, clad in blak or reed

The difference consists of the spelling ‘bokes’ in place of ‘bookes’, and the insertion (this would have been Skeat’s editorial decision) of a comma. More important than the nature or size (or consequence) of this difference, however, is the way that the print technology that has determined how we read Chaucer for so long must always tend toward Skeat’s simplicity. Mann’s Penguin edition, the most user-friendly we now have — and therefore destined to be the most read in future years — does not include variants at all. The Riverside Chaucer includes some variants in its ‘Textual Notes’ but it moves all of these to the back of the book. Complicate things as much as Manly and Rickert did with all the variants, and no one will read your text.

Online editions open out new possibilities for marrying simplicity to completeness. One can imagine a hypertext edition in which all the variants associated with a particular word, phrase, or line, would simply appear as a cursor passed over the text (much as the contents of a footnote will appear in a bubble when the cursor moves across the reference in a text written in Word). The paradox seems stark: only when the words of the text are lifted entirely away from any page can the complexity of the page be fully preserved and disseminated. And yet it is not a paradox if we think of such a hypertext as finally overcoming the limits of print technology. No longer shackled by the limits of mechanical reproduction, the digital age gives us a text that, precisely because it lacks physical form is supple enough to represent the complexity of that form.

Such a hypertext is not yet with us because entering the variants in the marked-up form that would make them available in this way is itself a huge undertaking (digital technology is never more powerful than the information human labor can provide for it). But an online edition such as Oxford’s is already sufficient to the task of making the complex simple in all the ways that a medieval text with many variants requires. If books must separate variants from the text of the Tales in precise proportion to their detail (include many and they must be placed at the back of the book; include all of them and you need several more books), but simply give yourself the virtual page in which an infinite amount of information may un-scroll in one column while the text sits happily, unmoved, in another, and all the variants of a text can accompany every word and phrase and line of that text at all times. Such an edition can also put the complexity of these variants in the hand of everyone — student and scholar alike — who has a computer and an internet connection.

Many libraries own neither Manly-Rickert nor Skeat. And even the copyright library in which I write these remarks, the Cambridge University Library, requires that the volumes of Manly-Rickert be fetched to its ‘West Room’, but keeps Skeat in its Rare Books Room (because it was published before 1900). To bring Manly-Rickert’s variants to Skeat’s text they must be couriered by a member of staff (a reader cannot transport them from West to Rare Books Room himself). Since neither set of volumes circulates I could not bring them home to compare with my own copies of the Riverside and Mann’s Penguin edition. These common editions should have been available on the open shelves (and I could have found them there and brought them to the Rare Books room myself) but, as it happened, on the day I was gathering these volumes together, the Penguin edition of the Tales was checked out.

None of these movements is anything more than tedious, and careful scholarship moves greater mountains of inconvenience very day. And yet these are obstacles that might well defeat the undergraduate or post-graduate who simply wanted to explore what variation might exist in the text of the Tales. And a scholar focused on the variants in the text of the Tales might more easily go beyond those variants (to thoughts about the patterns they display; to theories about the nature or reliability of the edited text itself) if it was easier to consult them. What everybody who reads the Canterbury Tales has lacked up until this point, in other words, is a way of accessing all the richness of the material form in which the Tales survives as a constant and necessary concomitant of a readable text. The representational power of digital technology enriches the works we have long known and loved by just such elaborations.

Christopher Cannon is a Professor of English at New York University and member of the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online editorial board. He teaches Middle English literature at New York University. He took his BA, MA and PhD at Harvard University, and then taught, successively, at UCLA, Oxford, and Cambridge. His PhD dissertation and first book, The Making of Chaucer’s English (1998) analyzed the origins of Chaucer’s vocabulary and style using an extensive database and purpose-built software to demonstrate that Chaucer owed much more to earlier English writers than had been recognized before. His second book, on early Middle English, The Grounds of English Literature (2004), developed these discoveries by means of a new theory of literary form. Most recently he has written a cultural history of Middle English.

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is coming soon. To discover more about it, view this series of videos about the launch of the project or read a series of blog posts on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only humanities articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image of Chaucer as a pilgrim from Ellesmere Manuscript in the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. The manuscript is an early publishing of the Canterbury Tales. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

By: Alice,

on 2/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

digitization,

text,

Virgil,

antiquity,

Humanities,

tablets,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

scholarly editions,

Andrew Zurcher,

Edmund Spenser,

Mantuan,

Marot,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Shepheardes Calender,

Theocritus,

thenot,

calender,

cuddie,

shepheardes,

eclogues,

Literature,

Education,

Add a tag

By Andrew Zurcher

The “Februarie” eclogue of Edmund Spenser’s pastoral collection, The Shepheardes Calender, was first published in 1579. It presents a conversation between two shepherds, a brash “Heardmans boye” called Cuddie and an old stick-in-the-mud named Thenot. The two of them meet on a cold winter day and get into an argument about age: Cuddie thinks Thenot is a wasted and weak-kneed whinger, while Thenot blames Cuddie for his heedless and slightly arrogant headstrongness. To support his position, Thenot tells a moralising tale about an ambitious young briar and a hoary oak. In his eagerness to flaunt his brave blooms full in the sun, the briar persuades a local husbandman to chop down the mossy tree; but the end of the tale turns bitter for the little plant when, deprived of the sheltering support of his onetime neighbour, he is utterly blown away in a heavy gale. Thenot is in the middle of applying the moral of his tale when Cuddie interrupts, and leaves in a huff – petulant and dismissive to the last. As the eclogue breaks off, the reader is caught in an old-fashioned and hackneyed dilemma: is it better to embrace the beautiful but rootless new, or cling to the solid, gnarled old?

June Aegloga Sexta. Source: New York Public Library.

poses this gnarled horn of a problem in the middle of a printed book that, itself, has already begun to play in a very material way with the tensions between antiquity and

newfangleness. Spenser’s eclogues are conspicuously modeled on those of

Theocritus and

Virgil,

Marot and

Mantuan. The poems were first published elaborated with E.K.’s prefaces, his introductions (or “Arguments”) to each of the twelve

“aeglogae,” and his explanatory notes. These annotations are presented in a Roman type that contrasts visually with the black letter of Spenser’s poetry, framing it in a style that emulated early modern editions of Virgil’s eclogues, as well as the theological and legal texts that, in this humanist period, were often produced entirely engulfed in glosses and comments. Each of the eclogues is also accompanied by a woodcut, done in a rough style, and concludes with an “embleme” apiece for each of the eclogue’s interlocutors. These archaising features belie the novelty of Spenser’s project – the first complete set of original pastoral poems in English, and a collection that, in its allegorical engagement with the history of England’s recent and successive reformations, put this country and its fledgling literary culture on the map. Here at last was England’s Virgil, said Spenser himself. Just look at his book. But is it an old book, or a new book? Is it new-old, or old-new? What is the meaning of the new, if it be not interpreted by the old?

One of the most exciting aspects digitizing works such as in the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) project is

William Shakespeare was born 450 years ago this month, in April 1564, and to celebrate Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is testing your knowledge on Shakespeare quotes. Do you know your sonnets from your speeches? Find out…

William Shakespeare was born 450 years ago this month, in April 1564, and to celebrate Oxford Scholarly Editions Online is testing your knowledge on Shakespeare quotes. Do you know your sonnets from your speeches? Find out…

This week, we're shining the spotlight on another one of our Place of the Year 2015 shortlist contenders: Cuba.

The post Place of the Year 2015 nominee spotlight: Cuba appeared first on OUPblog.