Electronic cigarettes are growing in popularity around the world. With the announcement of vape as our Word of the Year, we asked a number of scholars for their thoughts on this new word and emerging phenomenon.

* * * * *

“Electronic cigarettes (ECIGs) are a rapidly evolving group of products that are designed to deliver aerosolized nicotine to the user. If ECIGs are used in the short-term to help smokers quit tobacco use completely and then eliminate all nicotine intake, they have some potential to reduce the health risks that smokers face. However, ECIGs also present a potential public health challenge because of uncertainty regarding the long-term health effects of inhalation of an aerosol that contains, in addition to the dependence-producing drug nicotine, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, flavorants, and a variety of other chemicals. Very recent data demonstrate that ECIGs can be as effective as tobacco cigarettes in terms of the amount of nicotine delivered, raising the possibility that they also may be equally addictive. If ECIGs are as addictive as tobacco cigarettes, quitting them may be difficult for smokers who used them to stop smoking and for non-smokers, young and old, who began using them because ECIGs are marketed aggressively and flavored attractively. The rapid evolution of the product, coupled with the unknown effects of long-term inhalation of the aerosol highlight the need for ongoing, objective, empirical evaluation of these products with the goal of minimizing risk to individual and public health.”

— Thomas Eissenberg, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology and Co-director, Center for the Study of Tobacco Products, at Virginia Commonwealth University

“Vape is a practical solution to a recently-arisen lexical gap that points up the genius of English lexical expansion. It supplies a simple verb with predictable inflections (vaping, vaped), built on an already familiar pattern of consonant-vowel-consonant-silent e (as in bake, file, poke, rule, and hundreds of others). Vape also conforms to the one-syllable pattern of many verbs, standard and informal, denoting ingestion: eat, drink, chug, quaff, smoke, snarf, snort, whiff. Although the root vapor is from Latin, speakers have effortlessly nativized it by removing the unneeded second syllable.”

— Orin Hargraves, lexicographer, researcher of the computational use of language at the University of Colorado at Boulder, and author of many books, including It’s Been Said Before: A Guide to the Use and Abuse of Cliches.

“Vape is a great choice for Word of the Year, not just because 2014 was the Year of Vaping, but because it is aesthetically perfect for marketing vaporizing paraphernalia and taking over the eroding market for traditional smoking products. Think about it: smoking. It’s really an unattractive word related to other unattractive words, like choking and hacking. Hold that /o/ long enough and you’ll cough by the time you hit the /k/. Vape is hip — new vowels, new consonants, new look, same old addiction. It’s a stunning verbal makeover.”

— Michael Adams, Indiana University at Bloomington, author of Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon, Slang: The People’s Poetry, editor of From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages.

* * * * *

Headline image credit: Electronic Cigarettes by George Hodan via Public Domain Images.

The post Scholarly reflections on ‘vape’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By Michael Adams

It will be interesting to see how much of J.R.R. Tolkien’s several invented languages will appear in Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit. In a letter to his American publisher, dated 30 June 1955, Tolkien suspected there were limits to how much invented language readers would ‘stomach’ — to use his term. There are certainly limits to how much can be included in a film. American audiences, anyway, are subtitle averse.

Of Tolkien’s invented languages, Elvish receives most attention, not unreasonably, since it is illustrated most often in Tolkien’s works and most fully articulated in his manuscripts. Other languages are essential to The Lord of the Rings, however. When Gandalf reads out the delicately curved Elvish script on the One Ring in the rough-hewn Black Tongue of Mordor it represents so incongruously, Tolkien proves that some language — just the sound of it — can petrify us as surely as any Ringwraith. Tolkien’s languages aren’t suitable only for poetry or gnomic verses on rings. They also include the element of language most familiar to speakers speaking to one another every day, namely, names.

Tolkien as Philologist

When Tolkien came up with what sounded to him like a name, he would play with it a bit, experiment with its sound structure, and eventually a system of linguistically related names would emerge. Thus a family was invented, a family with relationships to other families in a mythical place, ready to take part in stories. As Tolkien explained in the letter already mentioned, “The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse. To me a name comes first and the story follows.” And in his lecture on creating languages, ‘A Secret Vice’ (1931), he wrote “the making of language and mythology are related functions” and an invented language, at least one developed at length, will inevitably “breed a mythology.”

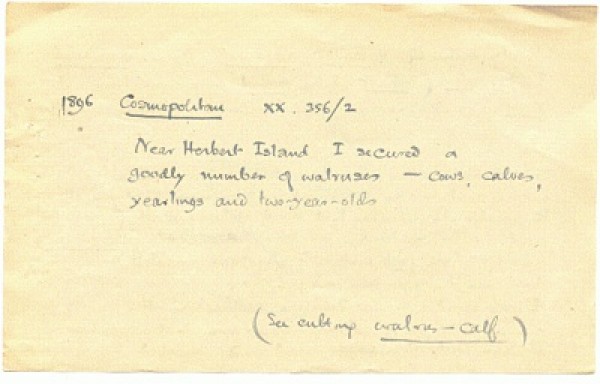

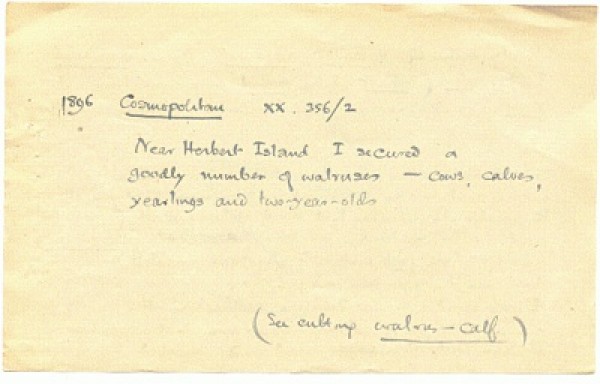

A slip written by J.R.R. Tolkien on the etymology of “walrus” during his years working for the Oxford English Dictionary. Image courtesy the Oxford University Press Archives.

Tolkien was always a philologist, whether in scholarship or fiction. He treated his fictional languages as though they were real, as though he were discovering rather than inventing them. In his scholarship, reconstruction of the sound system or grammar of languages like Old English and Old Norse was routine. For instance, he wrote ‘Appendix I: The Name “Nodens”’, in the Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Sites in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire, published by the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932). So, it isn’t in every library, but it has been helpfully reprinted in Volume 4 of the annual journal Tolkien Studies (2007). In it, you will find passages like this one: “Although it is perhaps vain to try and disentangle from the things told of Nuada any of the features of Nodens of the Silures in Gloucestershire, it is at least highly probably that the two were originally the same. This is borne out by the isolation of the name in Keltic [sic] material, the importance of Nuada (and of Nodens), and not least by the exact phonological equation of Nōdont- with later Nuadat.” This reads very much like a passage from one or another appendix to The Lord of the Rings, and if you read it without knowing it deals with a matter of linguistic and historical fact, you might well think it was fiction.

How to Name a Baggins

Many names in Tolkien’s fiction are not invented, or, at least, not invented by him. Nearly all of the names of dwarfs in The Hobbit can be found in Dvergatal or ‘Tally of the Dwarfs’ in the Old Norse poetic Edda, as can the Old Norse precursors of Gandalf and Thorin’s nickname, Oakenshield. Hobbit names are an interesting blend of borrowed and invented items. For instance, a few males of the Baggins family of Hobbits sometimes bear real — though indisputably outmoded — personal names, such as Drogo (name popular among the French nobility c1000 CE, but since, not so much), Dudo (name of a tenth-century Norman historian and ecclesiast), and Otho (name of a Roman emperor). Other masculine names are converted from surnames or words found in natural languages, such as Balbo, Bingo, Fosco, Largo, Longo, Minto, Polo, and Ponto. But still others appear to be well and truly invented by Tolkien, such as Bilbo, Bungo, and Frodo. Perhaps they were invented to sound and look like the borrowed and converted names, but more likely those were found to fit patterns implied by the invented ones.

The 1937 Allen & Unwin hardback edition cover designed by Tolkien.

Many female Bagginses were given English flower names, such as Daisy, Lily, Myrtle, Pansy, Peony, and Poppy. Others had personal names common in English and other natural languages, for instance, Angelica, Dora, Linda, and Rosa. And a few bore personal names converted from surnames, like Belba, or historical but unfamiliar personal names, like Prisca (name of a Roman empress). The repurposing of such names and words as names of Hobbits may be inventive yet not count as an invention. Yet the invention is not of the names themselves — not most of them, anyway — but of linguistic relations among the names and social relations, embedded in the linguistics, among those to whom they belong.

The names have no actual relation to one another. They are borrowed from Italian and Scots and Norman French, or in those few cases made up. Tolkien brought them into relation by means of their sound shapes: the masculine names, whatever the source, and for whatever genuine etymological reason, are all two syllables and end in -o, which is proposed as a mark of the masculine name in the naming practices of Bagginses. For female Bagginses, the flower names are a fashion that obscures the way gender is marked in Baggins names: Belba, Dora, Linda, Prisca, and Rosa are marked with the contrasting feminine -a. Among all of the flower names, the -a names suggest a diminishing but tenacious historical tendency. But all language changes, as do naming practices, and any reconstruction of personal names in a historical language must account for remnant forms, anomalies, and generational trends.

There and Back Again

Other Hobbit clans have different types of names from those of the Bagginses. Brandybuck names have a distinctly Celtic shape, given the profuse -doc suffix: Gormadoc, Marmadoc, Saradoc, and, of course, Meriadoc. The Tooks prefer names from medieval romance and beast epic: Adelard, Ferumbras, Flambard, Fortinbras (rather than Armstrong, which has a quite different shape), Isengrim, and Sigismund, for instance. The Longfathers have names constructed from Anglo-Saxon elements: Hamfast and Samwise, in which -wise may mean, as it sometimes does in Anglo-Saxon, ‘sprout, stalk’. Over the generations, clan marries into clan, and the names mingle and develop new patterns: the names are the genealogical architecture of a culture.

Through alliances and friendships, Hobbit culture reticulates into the wider web of cultural relationships across Middle Earth and deep into the mythology of which the story of Middle Earth is only a part. The linguistic bases for cultural relationship and contrast are woven tightly and everywhere into the fabric of Tolkien’s fiction. In the middle of the mythological pattern, Tolkien has pricked in the -o and the -a, suffixes that say something about who the Bagginses are, or who they think they are, something that allows one Baggins to find the Ring and another to destroy it, just in time.

Michael Adams teaches English language and literature at Indiana University. In addition to editing and contributing to numerous linguistic journals, he is the author of Slang: The People’s Poetry and Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon, and he is the editor of From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Naming of Hobbits appeared first on OUPblog.

Megan Branch, Intern

What do you think of when you think of slang? Maybe you think of a bunch of teenagers running around saying “OMG, like, LOL.” The truth is that everyone, not just young people, use slang –sometimes without even realizing it. In his new book, Slang: The People’s Poetry, Michael Adams suggests that our use of slang “outlines social space” and that “attitudes about slang partly construct group identity and identify individuals as members of groups”.

Adams, English language professor at Indiana University and author of several books on slang, writes that in addition to allowing slang users to be accepted into certain social groups, slang also acts as a barrier to keep those who aren’t “in the know” out. This is why someone over fifty may have trouble understanding the slang words of the under-twenty set. Below is a list , taken from Slang, of the top 10 slang words that are so hip they don’t even sound like slang.

1. Morning glory More than a flower, this slang term has existed since the early 1900s and has meant “something which or someone who fails to maintain an early promise” as well as, in the 1950s, “the first narcotic injection of the day.”

2. Gone Borneo This absurd-sounding phrase had a fairly short lifespan of about 10 years and was used in the 1980s to mean “intoxicated”.

3. Flash Still in use today, flash was used at least as far back as Charles Dicken’s Oliver Twist to mean “hip”.

4. Suck Although many people want this word to originate somewhere far more off-color, suck is simply a shortening of the phrases “suck eggs,” “suck rope,” and “suck wind”—all of which can be used to mean “disappointing.”

5. Wig It sounds like a hairpiece, but wig is the clipped form of “wig out,” a less widely-used synonym for “freak out.”

6. Duck A pretty, but “snob[by], stuck-up young woman,” who often requires a lot of “lettuce ‘cash in bills’” to please.

7. Pegging Used at a dance, much to her embarrassment, by Jo in Louisa May Alcott’s novel, Little Women.

“’I suppose you are going to college soon? I see you pegging away at your books—no, I mean studying hard,’ and Jo blushed at the dreadful ‘pegging’ which had escaped her.”

8. Bad Used “to mean its opposite, as well as ‘stylish, sexy, wonderful, formidably skilled’”.

9. Snack From a dictionary of terms “supposedly used by the criminal element” published in 1698 or 1699. After stealing your possessions, the thieves would snack ” ’share, go halves’ on them.”

10. Trouble & Strife A Cockney rhyming slang term that originated in London’s East End, trouble and strife is used to mean ‘the wife.’