new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Afghanistan, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 52

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Afghanistan in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Michelle,

on 3/9/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

Current Events,

Middle East,

Afghanistan,

9/11,

terrorism,

colbert,

archive,

CIA,

colbert report,

osama bin laden,

The Oxford Comment,

oxford comment,

ben daniels band,

*Featured,

michael scheuer,

scheuer,

osama,

laden,

counterterrorism,

cia’s,

podcast,

Biography,

Add a tag

What does Osama bin Laden really want from us? Listen to this podcast and find out.

Want more of The Oxford Comment? Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

You can also look back at past episodes on the archive page.

Featured in this Episode:

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism (recommended by bin Laden himself). His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden which he recently discussed on The Colbert Report (and this podcast!).

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism (recommended by bin Laden himself). His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden which he recently discussed on The Colbert Report (and this podcast!).

* * * * *

The Ben Daniels Band

By:

Aline Pereira,

on 3/3/2011

Blog:

PaperTigers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Canada,

Japan,

Afghanistan,

World Literacy,

Girls' Day,

Alaina Podmorow,

Canadian Women for Afghanistan,

Little Women for Little Women in Afghanistan,

Sally Armstrong,

Add a tag

Today is Girls’ Day in Japan and many girls will celebrating it with their families. I have written a post about the holiday in the past for PT. This year I’d like to draw your attention to girls in other parts of the world, namely in Canada and Afghanistan. Little Women for Little Women in Afghanistan is an organization started in 2007 by a Canadian girl named Alaina Podmorow in British Columbia. After hearing a stirring talk by writer and activist Sally Armstrong about the plight of women in Afghanistan, Alaina started to fundraise by hosting a silent auction which raised enough money to support four teachers’ salaries in Afghanistan. She then contacted the organization Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan and joined with them under the name she chose for her group and hence was Little Women for Little Women in Afghanistan born! Check out their website for more details.

Today is Girls’ Day in Japan and many girls will celebrating it with their families. I have written a post about the holiday in the past for PT. This year I’d like to draw your attention to girls in other parts of the world, namely in Canada and Afghanistan. Little Women for Little Women in Afghanistan is an organization started in 2007 by a Canadian girl named Alaina Podmorow in British Columbia. After hearing a stirring talk by writer and activist Sally Armstrong about the plight of women in Afghanistan, Alaina started to fundraise by hosting a silent auction which raised enough money to support four teachers’ salaries in Afghanistan. She then contacted the organization Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan and joined with them under the name she chose for her group and hence was Little Women for Little Women in Afghanistan born! Check out their website for more details.

By: Lauren,

on 3/2/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

newsweek,

muslim,

morrison,

CIA,

colbert report,

Al-Qaeda,

osama bin laden,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

michael scheuer,

scheuer,

colbertnation,

patt,

osama,

laden,

US,

Current Events,

Iraq,

stephen colbert,

Media,

Middle East,

Afghanistan,

Islam,

terrorism,

Military,

terrorist,

colbert,

Add a tag

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism. His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden, a much-needed corrective, hard-headed, closely reasoned portrait that tracks the man’s evolution from peaceful Saudi dissident to America’s Most Wanted.

Among the extensive media attention both the book and Scheuer have received so far, he was interviewed on The Colbert Report just this week.

Interested in knowing more? See:

0 Comments on Michael Scheuer sits down with Stephen Colbert as of 1/1/1900

Words in the Dust by Trent Reedy

This is the wrenching tale of Zulaikah, an Afghani girl who lives with a cleft palate that has earned her the nickname of Donkeyface from the bullies in her neighborhood. It is a modern story, set after the defeat of the Taliban. Zulaikah lives with a harsh taskmaster of a stepmother, her beloved older sister, and two younger brothers. Despite her face, she is the one her stepmother sends to the market for supplies, giving the other children a chance to mock her. With the Americans in town, Zulaikah is offered the chance to have her face repaired. She also meets Meena, an old friend of her late mother who offers to teach her to read. These are immense opportunities for her, but will she be allowed to take advantage of them?

Reedy is a debut author who served in Afghanistan with the National Guard. Zulaikah’s story is based on a girl he met in Afghanistan. Reedy has created a marvelous lens for readers to better understand Afghanistan, its culture and its people. The day-to-day life shown here is so very different from our own, that one never forgets that this is a different country. Yet Zulaikah’s hopes and dreams are universal. So this book manages to offer a view of a foreign country at the same time it is showing our united humanity.

Zulaikah is a heroine who has seen unthinkable things, lives with a very visible disability, and yet remains hopeful about the future. She is a girl living in a culture that devalues women and girls, and while she searches for someone to teach her to read, she is not straining against the culture she is a part of. That is a large part of what makes this book so successful. This is a girl who is a product of her family and culture, yet radiant with inner beauty and always hope.

This is a particularly timely book that offers a perspective of modern Afghanistan. It also offers a very human character who will have you viewing news of Afghanistan differently, now with a spirited girl to inspire understanding. Appropriate for ages 11-13.

Reviewed from ARC received from Scholastic.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 1/20/2011

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Afghanistan,

multicultural children's literature,

middle grade realistic fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Trent Reedy,

2011 reviews,

2011 middle grade fiction,

Uncategorized,

middle grade fiction,

Add a tag

Words in the Dust

Words in the Dust

By Trend Reedy

Arthur A. Levine Books (an imprint of Scholastic)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0-545-26125-8

Ages 11 and up.

On shelves now.

A children’s book, written by a soldier about an Afghani girl, set in the recent past. That’s a toughie. There are a lot of easier books out there to review too. Why aren’t I writing one about the adorable little girl who wants to be Little Miss Apple Pie or the one about the cute dog that wants to find its home? Well, sometimes you have to step out of your comfort zone, which I suspect is what author Trent Reedy wanted to do here. With an Introduction by Katherine Paterson and enough backmatter to sink a small dinghy, Reedy takes a chance on confronting the state of the people of Afghanistan without coming off as imperialist, judgmental, or a know-it-all. For the most part he succeeds, and the result is a book that carries a lot more complexity in its 272 pages than the first 120 or so would initially suggest. Bear with it then. There’s a lot to chew on here.

Zulaikha would stand out in any crowd. It’s not her fault, but born with jutting teeth and a cleft upper lip she finds herself on the receiving end of the taunts of the local boys, and sometimes even her own little brother. Then everything in her life seems to happen at once. She’s spotted by an American soldier, who with his fellows manages to convince their captain to have Zulaikha flown to a hospital for free surgery. At the same time she makes the acquaintance of a friend of her dead mother, a former professor who begins to teach her girl how to read. Top it all off with the upcoming surprise marriage of Zeynab, Zulaikha’s older sister, and things seem to be going well. Unfortunately, hopes have a way of becoming dashed, and in the midst of all this is a girl who must determine what it is she wants and what it is the people she cares about need.

I approach most realistic children’s fiction with a great deal of trepidation, particularly when it discusses topical information. The sad truth of children’s books is that they are perfect containers for didacticism, even if you did not mean for that to be the case when you begin. With that in mind I read the first 120 pages of the story warily. I wasn’t certain that I liked what I saw either. Seemed to me that this book was indeed showing an in-depth portrait of Afghanistan, beauty, warts, and all, while the Americans were these near saviors, picking a poor girl out of the crowd upon whom to bestow free surgery out of the goodness of their golden glorious hearts. Fortunately, by the time we got to page 120 we saw the flip side of the equation. Yes, the Americans are perky and western and what have you. They’re also doofuses. Sometimes. They sort of blunder about Afghanistan without any recognition of the cultural courtesies they’re supposed to engage in. They merrily serve their Muslim guests food made out of pigs, unaware of what they’re doing. At one point Zulaikha’s father grows increasingly angry with them for their distrust of common Afghan workers (watching builders at gunpoint so that none of them steal tools) as well as their conversational blunders. Don’t get me wrong. The Americans are generally seen as good blokes. But I was worried that this book was going to be one sweet love song to the American invasion, and it’s not that. It’s nuanced and folks are allowed to be both good and bad. Even the ones writing the book.

I still got nervous, though. I desperately did not want this

ABC News senior White House correspondent Jake Tapper has landed a book deal with Little, Brown and Company to write Enemy In the Wire about a major battle in Afghanistan.

ABC News senior White House correspondent Jake Tapper has landed a book deal with Little, Brown and Company to write Enemy In the Wire about a major battle in Afghanistan.

Geoff Shandler acquired the book from Christy Fletcher at Fletcher and Company. In 2001, Tapper (pictured, via) published Down and Dirty with Little, Brown.

Here’s more about the book, from the release: “[It] will tell the investigative and inspiring story of the 54 US soldiers who were attacked by and ultimately (after more than 18 hours of fighting) prevailed over 300-400 Taliban at Combat Outpost Keating in northeast Afghanistan. Tapper will detail the battle and the soldiers’ heroism and valiant service under fire and tell their stories, those of their loved ones, and those of the eight US troops killed that day. He will also investigate the unusual and compromising geography of the camp — tucked in a vulnerable valley surrounded by three heavily forested mountains near the Pakistan border, and explore the history of the camp within the context of the larger mission in Afghanistan.”

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By: Elvin Lim,

on 9/14/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

A-Featured,

middle east,

Afghanistan,

President Barack Obama,

health-care reform,

Tea Party Movement,

Elvin Lim,

gibbs,

Elections 2010,

anti-intellectual presidency,

lining,

Robert Gibbs,

mahmoud abbas of,

already conceded,

and president,

higher approval,

Add a tag

By Elvin Lim

The “Summer of Recovery” has failed to materialize, and with that, the White House has had to start planning for 2012 earlier than expected.

After all, White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs had already conceded this summer that the House may fall to Republican hands. (Nancy Pelosi didn’t like the sound of his prescience then, but Gibbs was merely thinking strategically for his boss.) The one thing Democrats have going for them is that nearly every political commentator believes that an electoral tsunami awaits Democrats this fall, which means that they have low expectations on their side. And because the Democrats currently have a healthy majority, it would be nearly impossible that the flip will generate a Republican majority bigger than the one Democrats now enjoy. Victory for the Republicans would not taste so sweet because it would be fragile.

There is a silver lining inside this silver lining for the White House. If Republicans take control of the House, then at noon on January 3, 2011, President Obama will finally be able to do what presidents do best – blame the stalled progress on his domestic agenda on congressional intransigence, and switch to the domain in which presidents are able to act (and receive credit) unilaterally – foreign policy.

About a week and a half ago, Obama appeared to be embarking on this strategy, when he met with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Mahmoud Abbas of the Palestinian Authority. Whereas his second Oval Office address started with foreign policy issues and meandered awkwardly toward the economy (because the President was still hoping for a “summer of recovery”), the President’s first press conference inverted this order of priorities.

This press conference was delivered in the middle of the work day. It was directed to Washington elites and insiders, not the American public, for whom more talk of the economy would have been politically appropriate this election year. But the president began with the economy, but then ended with the Arab-Israeli conflict – displaying not only the agenda-setting power of the media to determine what presidents talk about, but also the instinct of presidents (even liberal ones) to withdraw to foreign policy as the presidential domain when domestic policy is not producing political credit for them.

It is no coincidence that very few Democratic candidates are campaigning on healthcare reform, even though it is the signature accomplishment of the Obama presidency and Democratic congress and the topic which headlined the political discussions of 2009. This is why Obama did not mention healthcare reform at all in his first and second Oval Office addresses, and he only brought it up haltingly and defensively in his first press conference last Friday.

With unemployment still at about 9.6 percent, everyone knows that the preeminent issue for Election 2010 is the economy. But Obama actually has, by a 10-point margin, higher approval numbers in his capacity as Commander-in-Chief than his handling of the economy. The White House realizes that the lack of results or higher casualties in Afghanistan doesn’t matter. What matters is that Obama is doing exactly what a Republican president would have done in Afghanistan and when there is nothing to fight about, the public approves.

After spending half of his first term on an ambitious domestic agenda for which he has gotten no credit but only blame, Obama may fin

By: Lauren,

on 8/23/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

Current Events,

Iraq,

A-Featured,

Afghanistan,

United Nations,

omar,

unicef,

child soldiers,

Guantanamo,

Social Work,

recruitment,

juvenile court,

omar khadr,

paris principles,

pow,

khadr,

grenade,

mapp,

speer,

optional,

Add a tag

By Susan C. Mapp

On December 23, 2002, the United States ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict. This document defines a “child soldier” as a person under the age of 18 involved in hostilities. This raises the minimum age from the age of 15 set in the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Neuroscience is now providing us with the tools to see what many have long suspected: the adolescent brain has not yet fully developed. In particular, the prefrontal cortex, which regulates complicated decision-making and calculation of risks and rewards is not yet fully developed. The American Bar Association used this knowledge in its support of the ban on the death penalty for minors.

Article 7 of this document states that nations who are parties to it will cooperate in the, “rehabilitation and social reintegration of persons who are victims.” The Declarations and Reservations made by US related primarily its recruitment of 17-year-olds and noting that the ratification did not mean any acceptance of the Convention on the Rights of the Child itself, nor the International Criminal Court, thus indicating its acceptance of Article 7.

However, the United States frequently detains and incarcerates child soldiers. The United Nations has noted the “presence of considerable numbers of children in United States-administered detention facilities in Iraq and Afghanistan” (p.6). The New York Times states the U.S. report to the UN regarding its compliance with the Optional Protocol states that it has held thousands of children in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2002. The same report also states that a total of eight children have been held at Guantanamo Bay.

The United States is currently in the process of trying a child soldier who has been held at Guantanamo Bay for the past 8 years. Omar Khadr, a Canadian citizen, is accused of throwing a grenade that killed an American soldier, Sgt. Christopher Speer. Omar was 15 years old at the time, well below the minimum age for child soldiers. The head of UNICEF, a former U.S. national security advisor, has stated his opposition to the trial:

The recruitment and use of children in hostilities is a war crime, and those who are responsible – the adult recruiters – should be prosecuted. The children involved are victims, acting under coercion. As UNICEF has stated in previous statements on this issue, former child soldiers need assistance for rehabilitation and reintegration into their communities, not condemnation or prosecution.

The Paris Principles, principles and guidelines on children associated with armed groups, was developed in 2007 to provide guidance on these issues. Developed by the United Nations, it has been endorsed by 84 nations as of 2009, not including the United States. It states that “Children … accused

By:

Aline Pereira,

on 8/19/2010

Blog:

PaperTigers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Picture Books,

Reading Aloud,

Pakistan,

Afghanistan,

Books at Bedtime,

reading aloud to children,

floods,

Rukhsana Khan,

refugee children,

children's books about refugees,

Ronald Himmler,

The Roses in My Carpet,

Add a tag

A young Afghan boy shares his life and dreams for the future with us in The Roses in My Carpets by Rukhsana Khan and illustrated by Ronald Himler (Holiday House, 1998), a beautiful, thought-provoking picture book set in a refugee camp in Pakistan. He doesn’t like school but loves the afternoons he spends weaving carpets from brightly colored threads that all hold special meaning for him: although “Everything in the camp is a dirty brown, so I do not use brown anywhere on my carpets.” One day his work is interrupted by the shocking news that his sister has been badly hurt. He runs to the hospital. His mother is already there, too distraught to think rationally. Our young narrator takes charge, sending his mother home while he waits for news at the hospital. Fortunately, this being a children’s story, the news is good – which in turn allows for a breathing space that alters the nightmare of conflict he describes at the beginning of the book: that night his dreams open up to allow a tiny space out of danger for him and his beloved family.

A young Afghan boy shares his life and dreams for the future with us in The Roses in My Carpets by Rukhsana Khan and illustrated by Ronald Himler (Holiday House, 1998), a beautiful, thought-provoking picture book set in a refugee camp in Pakistan. He doesn’t like school but loves the afternoons he spends weaving carpets from brightly colored threads that all hold special meaning for him: although “Everything in the camp is a dirty brown, so I do not use brown anywhere on my carpets.” One day his work is interrupted by the shocking news that his sister has been badly hurt. He runs to the hospital. His mother is already there, too distraught to think rationally. Our young narrator takes charge, sending his mother home while he waits for news at the hospital. Fortunately, this being a children’s story, the news is good – which in turn allows for a breathing space that alters the nightmare of conflict he describes at the beginning of the book: that night his dreams open up to allow a tiny space out of danger for him and his beloved family.

Reading a story that includes issues of conflict and hurt needs plenty of thinking and discussion space around it, especially at bedtime – but Rukhsana Khan has written this story so deftly that they too will be comforted by the ending. This wonderful book includes a lot of incidental detail, such as the muezzin calling people to prayer and the boy’s musings about his overseas sponsor. Particularly convincing is the way the boy and his mother can hardly eat at the end of the day, after their terrible fright; and also the reality depicted of a boy who is very mature – who has had to grow up too quickly and take adult responsibilities on his shoulders. The attention to detail also carries over into the fine ilustrations – and young readers, and perhaps adults too, may be particularly struck by the mud buildings in the refugee camp.

I have included The Roses in My Carpet in my Personal View for our current issue of PaperTigers, which focuses on Refugee Children. Rukhsana also talks about the book in her interview with us last year; and do listen to her reading it here. On her blog, she has been discussing Ramadan recently – and I particularly enjoyed this post with an Afghan fable. Yesterday Aline pointed to some books for children that focus on Ramadan – including another of Rukhsana’s…

And please, please spare a thought for all those caught up in the floods in Pakistan, including Afghan refugees like the boy and his family in The Roses in my Carpets. If you’re looking for a charity who are sending relief, take a look at Sally’s post for some links.

By: Lauren,

on 6/29/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

accidental guerrilla,

David Patraeus,

Stanley McChrystal,

patraeus,

counterinsurgency,

David Kilcullen,

afghan campaign,

isaf,

mchrystal,

Law,

Politics,

Current Events,

Iraq,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Afghanistan,

nato,

Add a tag

David Kilcullen is a former Senior Counterinsurgency Advisor to General David Patraeus in Iraq as well as a former advisor to General Stanley McChrystal, the U.S. and NATO commander in Afghanistan. Kilcullen is also Adjunct Professor of Security Studies, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, a Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, and the author of The Accidental Guerrilla (2009). His new book, Counterinsurgency, is a no-nonsense picture of modern warfare informed by his experiences on the ground in some of today’s worst trouble spots–including Iraq and Afghanistan. In this excerpt, Kilcullen shares a few insights as to how progress in the Afghan campaign can be properly tracked and assessed.

WHY METRICS MATTER

In 2009 in Afghanistan, ISAF seems to be in an adaptation battle against a rapidly evolving insurgency that has repeatedly absorbed and adapted to past efforts to defeat it, including at least two previous troop surges and three changes of strategy. To end this insurgency and achieve peace, we may need more than just extra troops, new resources, and a new campaign plan: as General Stanley McChrystal has emphasized, we need a new operational culture. Organizations manage what they measure, and they measure what their leaders tell them to report on. Thus, one key way for a leadership team to shift an organization’s focus is to change reporting requirements and the associated measures of performance and effectiveness.

As important, and more urgent, we need to track our progress against the ISAF campaign plan, the Afghan people’s expectations, and the newly announced strategy for the war. The U.S. Congress , in particular, needs measures to track progress in the “surge” against the President Obama’s self-imposed eighteen-month timetable. To be effective, these measures must track three distinct but closely related elements:

1. Trends in the war (i.e., how the environment, the enemy, the population, and the Afghan government are changing)

2. ISAF’s progress against the campaign plan and the overall strategy including validation (whether we are doing the right things) and evaluation (how well we are doing them)

3. Performance of individuals and organizations against best-practice norms for counterinsurgency, reconstruction, and stability operations

Metrics must also be meaningful to multiple audiences, including NATO commanders, intelligence and operations staffs, political leaders, members of the legislature in troop-contributing nations, academic analysts, journalists, and–most important–ordinary Afghans and people around the world.

We should also note that if metrics are widely published, then they become known to the enemy, who can “game” them in order to undermine public confidence and perpetuate the conflict. Thus, we must strike a balance between clarity and openness on the one hand and adaptability and security on the other.

SHARED DIAGNOSIS

Because

Wanting Mor Rukhsana Khan

After Jameela's mother dies, her father takes her from their small Afghani village to Kabul. In the city, Jameela's devout and conservative following of Islam is seen as proof that she is nothing more than a slack-jawed yokel. Her refusal to change, to do what she considers sinful acts (such as going without her

porani to cover her hair and face) leads her father to ultimately abandon her.

Jameela finds her way to an orphanage where she learns to read and write and tries to live up to her mother's advice, "If you cannot be beautiful, you should at least be good. People will appreciate that."

While definitely a bleak premise, this novel is ultimately hopeful. I most appreciated that as Jameela grew, she never did cave on what she felt was the right way to practice her faith. Eventually, she chooses to wear the

chadri (burka), as it frees up her hands so she doesn't need to always draw her

porani across her face to cover it. I also liked her confusion about the role of Americans. One on hand, the American soldiers are the ones who killed her entire extended family, they are the ones who bombed Kabul, but they're also the ones who pay for the orphanage and give Jameela surgery to correct her cleft lip. She never can decide if they're good or bad or somewhere in between and I think this reflection and indecision are very real, especially for a girl from a traditional village that didn't see the effects of the removal of the Taliban like they did in larger cities like Kabul.

A beautiful book.

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

Nasreen’s Secret School: a True Story from Afghanistan by Jeanette Winter

The author of The Librarian of Basra brings readers another true story from the Middle East. This is the story of Nasreen, a young Afghan girl who has not spoken since her parents disappeared. Her grandmother hears about a school for girls which is secret and forbidden. In the hopes of bringing Nasreen out of her silence, her grandmother enrolls her. The girls attending the school must be clever. They must leave alone or in small groups. They must hide their schoolwork if they are inspected by soldiers. Little by little, Nasreen and her classmates learn to read and write. And little by little, Nasreen begins to join this community of women and girls.

Winter’s illustrations are are framed by lines and painted in thick acrylic paints. This gives them the feel of more traditional work, though they depict modern life. Though the situation is complex, Winter manages to tell the story in short sentences. American children will learn of a society where people disappear and girls are not allowed to be educated, all explained at their level of comprehension. Expect lots of questions and discussion after sharing this true story with children.

An important piece of work, this picture book allows children to glimpse another culture that is now intertwined with our American one. Appropriate for ages 4-8.

Reviewed from copy received from publisher.

Also reviewed by A Year in Reading.

By: Rebecca,

on 10/27/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

democracy,

Politics,

Science,

Current Events,

president,

Geography,

A-Featured,

Media,

Afghanistan,

Harm de Blij,

power of place,

destiny,

Karzai,

Vietna,

Add a tag

Harm de Blij is the John A. Hannah Professor of Geography at Michigan State University. The  author of more than 30 books he is an honorary life member of the National Geographic Society and was for seven years the Geography Editor on ABC’s Good Morning America. His most recent book, The Power of Place: Geography, Destiny, and Globalization’s Rough Landscape, he reveals the rugged contours of our world that keep all but 3% of “mobals” stationary in the country where they were born. He argues that where we start our journey has much to do with our destiny, and thus with our chances of overcoming obstacles in our way. In the article below he looks at Afghanistan and Vietnam.

author of more than 30 books he is an honorary life member of the National Geographic Society and was for seven years the Geography Editor on ABC’s Good Morning America. His most recent book, The Power of Place: Geography, Destiny, and Globalization’s Rough Landscape, he reveals the rugged contours of our world that keep all but 3% of “mobals” stationary in the country where they were born. He argues that where we start our journey has much to do with our destiny, and thus with our chances of overcoming obstacles in our way. In the article below he looks at Afghanistan and Vietnam.

Hamid Karzai’s victory in Afghanistan’s disputed presidential election has created a diplomatic and strategic dilemma that is producing some troubling commentary by American officials and much strident criticism in the media. The Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, John Kerry, in an interview from Kabul on Face the Nation on October 19, stated that the U.S. is facing strategic decisions “without an adequate government in place.” Vice President Joe Biden has been unsparing in his disparagement of Karzai, whose government and family are linked to corruption and drug dealing. In an October 14 column in the New York Times, Thomas Friedman laments the “tainted government” of Afghanistan and the “massive fraud” engaged in by President Karzai to secure his re-election, arguing for a runoff to secure a more “acceptable” government to replace the one now in power, so as “to stabilize Afghanistan without tipping America into a Vietnam.”

Comparisons between Afghanistan and Vietnam are frequently drawn these days, but the two contingencies are starkly different. Yet what happened in Vietnam in 1963 suggests caution in Afghanistan today. At that time, South Vietnam was in turmoil as the Viet Cong were gaining in remote northern rural areas; 12,000 American “advisers” were supposedly training South Vietnamese forces to shore up the South’s defenses. South Vietnam’s President Ngo Dinh Diem, facing growing Buddhist resistance marked gruesomely by public self-immolations by numerous monks, was unpopular with American policymakers. His autocratic methods, reputation for corruption, and harsh response to his religious opponents elicited severe criticism from American leaders and pundits. When President Diem asked the United States government to reduce the number of American advisers in his country, he lost what little support he retained in Washington – and found his political base weakened at home.

On November 1, 1963 a military coup carried out by soldiers, some of whom had benefited from the presence of American advisors, overthrew President Diem, who was summarily executed. In official and media commentary in the United States afterward, Diem got little obituary solace. In South Vietnam, a so-called revolutionary council took power and inaugurated a fateful period of more compliant association with American policymakers.

American insistence on an electoral runoff in Afghanistan and Washington’s apparent belief that President Karzai’s opponent, if victorious, would form a less corrupt government may be misplaced. The rules of political, social, and economic engagement in Afghanistan that have prevailed for centuries will not be changed by an electoral runoff that may not only fail to alter the outcome but could risk chaos arising from the rekindling of hopes dashed and buried by Karzai’s victory. Afghanistan remains a deeply-divided country in which warlords, tribal chiefs, insurgents, brazen criminals, and a small cadre of courageous Kabul-based progressives are just some of the parties looking for their piece of the action; not for nothing do international monitors rank this as one of the world’s most corrupt societies. Karzai, with his merits as well as faults, has come to symbolize and stabilize the state; foreigners forcing a runoff may leave him either victorious but severely weakened or defeated with no guarantee of a superior successor. Add to this the alternate prospect of an adversarial “power-sharing” government and an ongoing political crisis, and it appears that one lesson of Vietnam, at least, is going unheeded.

By: Rebecca,

on 10/6/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

Current Events,

American History,

A-Featured,

Media,

Afghanistan,

Barack Obama,

Jon,

David,

Harry,

Commander in chief,

Harry Truman,

Douglas,

MacArthur,

armchair generals,

Commander-in-chief,

David Patraeus,

Douglas MacArthur,

Jon Kyl,

Stanley McChrystal,

armchair,

generals,

Patraeus,

Truman,

Kyl,

Obama,

Barack,

Stanley,

McChrystal,

Add a tag

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and  author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at General Stanley McChrystal. See his previous OUPblogs here.

author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he looks at General Stanley McChrystal. See his previous OUPblogs here.

Sarah Palin is not the only person going rogue these days. In a speech to the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London last Thursday, General Stanley McChrystal advocated for an increase in American troop levels in Afghanistan by 40,000, while rumors that the General would resign his command if his request was not honored remain unquashed. A week before, McChrystal appeared on CBS’s “60 minutes” to spread the word that help is needed in Afghanistan. And before that, he, or one of the supporters of his proposal, leaked a confidential report of his petition to the president to Bob Woodward of The Washington Post, which published a redacted version of it. These are the political maneuverings of a General who understands that wars abroad must also be waged at home.

But, the General fails to understand that the political war at home is not his to fight, and his actions in recent weeks have been out of line. No new command has been issued yet about Afghanistan, but General McChrystal has taken it upon himself to let the British and American public know how he would prefer to be commanded. As it is a slippery and imperceptible slope from preemptive defiance to actual insubordination, as President Harry Truman quickly came to realize about General Douglas MacArthur, President Obama needs to assert and restore the chain of command swiftly and categorically.

As Commander of Special Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq from 2003 to 2008, McCrystal was given free reign to bypass the chain of command. This leeway allowed McCrystal’s team to capture, most illustriously, Saddam Hussein during the Iraq war. But it may have gotten into his head that the discretion Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney granted to him has carried over to his command in Afghanistan. No doubt, McCrystal has been emboldened by supporters of a troop increase in Afghanistan, who have recently chastized President Obama for not having had more meetings with McChrystal. Others, like Senator John Kyl (R-AZ) have on CNN accused the “people in the White House … (as) armchair generals.”

Those who assault the principle of civilian control of the military typically and disingenuously do so obliquely under the cover of generals and the flag, for they dare not confront the fact that the constitution unapologetically anoints an armchair general to lead the military. It is worth noting, further, that in the same sentence in which the President is designated “Commander-in-Chief,” the Constitution states, “he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments.” The President may require the opinion of any cabinet secretary should he so choose to do so, but he isn’t even constitutionally obligated to seek the opinion of the Secretary of Defense, to whom General McChrystal’s superior, General David Petraeus, reports via the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. General McChrystal has spoken out of turn even though his chain of command goes up quite a few more rings before it culminates in the person seated on an armchair in the Oval Office, and yet I doubt he would take kindly to a one-star general speechifying against his proposal for troop increases in Afghanistan.

Dwight Eisenhower, when he occupied the armchair in the Oval Office, wisely warned of the “Military Industrial Complex” because he understood that it was as much an organized interest as was the Liberal Welfare State, Wall Street, or what would become the Healthcare Industrial Complex. No “commander on the ground” will come to the President of the United States and not ask for more manpower and resources, and Eisenhower understood that the job of the armchair general was to keep that in mind.

Let us not rally around military generals and fail to rally around the Constitution. Inspiring as the Star Spangled Banner may appear flying over Fort McHenry, we will do better to stand firm on the principles etched on an older piece of parchment. As Truman wrote in his statement firing General Douglas MacArthur,

“Full and vigorous debate on matters of national policy is a vital element in the constitutional system of our free democracy. It is fundamental, however, that military commanders must be governed by the policies and directives issued to them in the manner provided by our laws and Constitution.”

By: Kirsty,

on 8/20/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

UK,

Politics,

Current Events,

Iraq,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Afghanistan,

9/11,

terrorism,

World History,

ira,

war on terror,

Al-Qaeda,

richard english,

Bader Meinhof,

northern ireland,

Add a tag

Richard English was born in 1963 in Belfast, where he is Professor of Politics at Queen’s University. He is a frequent media commentator on Irish politics and history, and on terrorism, including work for the BBC, ITN, Sky News, NPR, Newsweek and the Financial Times. His latest book is Terrorism: How to Respond, which draws on over twenty years of conversations with terrorists themselves, and on analysis of a wide range of campaigns - Algeria, Bader Meinhof, The Red Brigade, ETA, Hezbollah, the IRA, and al-Qaeda - to offer both an authoritative, accessible analysis of the problem of terrorism, and a practical approach to solving it. In the original post below, Professor English lays out what he sees as the seven key elements in responding to terrorist violence.

This summer’s fatal terrorist attacks in Afghanistan, Spain and Iraq in their various ways reflect a paradoxical reality: despite the unprecedented efforts made since 9/11 to combat terrorist violence, the terrorist problem remains at least as prevalent as it was before the commencement of the ‘War on Terror’.

Indeed, the situation has in some ways grown worse. The number of terrorist incidents recorded globally in 2001 was 1732. By 2006 – five years into the War on Terror – the figure had risen to 6659. The monthly fatality rate from terrorism in the years immediately preceding 9/11 was 109; in the five years after 9/11, the monthly death-toll from terrorism rose to 167 (and this excluded deaths from attacks in Afghanistan and Iraq – with those included, the monthly death-toll rose to 447).

Indeed, the situation has in some ways grown worse. The number of terrorist incidents recorded globally in 2001 was 1732. By 2006 – five years into the War on Terror – the figure had risen to 6659. The monthly fatality rate from terrorism in the years immediately preceding 9/11 was 109; in the five years after 9/11, the monthly death-toll from terrorism rose to 167 (and this excluded deaths from attacks in Afghanistan and Iraq – with those included, the monthly death-toll rose to 447).

Of course, there are no easy solutions to the terrorist problem. The longevity of this form of violence is a testament to that. But this long history of terror is, perversely, a tremendous resource as we seek to deal with this global, murderous challenge. For we do, in fact, have a huge body of experience to draw on as we consider how best to deal with the terrorist threat. There are – or should be – a long list of ‘known knowns’ in terms of what we should and should not do about terrorism.

The difficulty tends to be this: each state faces each its own new terrorist crisis in effectively amnesiac fashion. Depressingly for those of us who research the history of terrorism, the same mistakes tend to be made each time, as though the lessons required re-learning. I remember a conversation with a scholar in Washington DC in 2006, in which I suggested that the US might have learned far more than it apparently had about how to deal with terrorism, from historically-informed scrutiny of what other states had been through. ‘Ah, but we have to see our own crisis as exceptional,’ I was told. This is, perhaps, true enough as a depiction of prevalent opinion. But it is no less depressing, and damaging, for that.

In 2003 I published a history of the IRA. At that time, the IRA was in the process of leaving history’s stage just as the post-9/11 crisis meant that terrorism itself was becoming a global preoccupation as never before. So it seemed worthwhile to try to set out the lessons of history – Irish, but also drawn from other settings – in a systematic and accessible way, to try to address the problem of what we should do when the next terrorist crisis strikes.

In 2003 I published a history of the IRA. At that time, the IRA was in the process of leaving history’s stage just as the post-9/11 crisis meant that terrorism itself was becoming a global preoccupation as never before. So it seemed worthwhile to try to set out the lessons of history – Irish, but also drawn from other settings – in a systematic and accessible way, to try to address the problem of what we should do when the next terrorist crisis strikes.

My argument as a result of that process is that we can only effectively respond to terrorism if we learn the lessons of terrorism’s long history, but that we can only learn those lessons if we adopt a proper means of explaining terrorism, and that we can only explain it if we are honest and precise about exactly what terrorism is in the first place. So, what is terrorism? Why do people resort to terror? What can we learn from terrorism past? How should we respond?

The seven key elements in a response to terrorist violence, as I see them, are:

First, learn to live with it. Politicians have all too often tried to give the impression of a resolve to uproot terrorism altogether, which is self-defeating and unrealistic. Individual terrorist campaigns will come to an end, terrorism itself will not, and our best approach is to minimize and contain it.

Second, where possible, address the root causes and problems which generate awful terrorist violence. This will not always be possible (neither the goals of the Baader-Meinhof group nor of Osama bin Laden could be delivered). But there are moments in history when effective compromise can be reached, normally after terrorist groups themselves recognize that their violence is not bringing anticipated victory, and that a turn to more conventional politics makes sense.

Third, avoid an over-militarization of response. There is an understandable temptation after terrorist atrocities to respond with military muscle, and this can have beneficial effects. It has also, on very many historical occasions, back-fired, with rough-handed military action and occupation stimulating that very terrorism which it was intended to stifle.

Fourth, recognize that high-grade intelligence is the most effective resource in combating terrorist groups. From 1970s Germany to 1990s Northern Ireland there have been many cases where intelligence has decisively aided the constraining of terrorist campaigns.

Fifth, adhere to orthodox legal frameworks and remain wedded to the democratically produced framework of law. All too often the Abu Ghraib pattern has been evident, with the state transgressing the line which distinguishes its own legal activity from illegal brutality: such transgressions tend to strengthen rather than undermine terrorist violence.

Sixth, ensure the coordination of security, financial, technological and other counter-terrorist efforts, both between different agencies of the same state, and between different states allied in the fight against terrorist violence.

Seventh, maintain strong credibility of public response. Any resort to implausible caricatures of one’s enemies will prove counter-productive among that constituency which is potentially supportive of terrorist violence but likely – if presented with credible alternatives – to recognize the futility as well as the appalling bloodiness of terrorist action.

All of the above points were ignored during the post-9/11 response of the War on Terror, and each of these errors has made our current position more difficult.

Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Bordersby Didier Lefèvreillustrated by Emannuel GuibertFirst Second Books 2009I don't know how to explain this. There are books you read that pry open a whole world you never knew existed. I mean, you've heard of places like Afghanistan and Pakistan, you've heard of small villages living in remote regions, you know organizations like Doctors

© Kathleen Rietz

© Kathleen Rietz

As you celebrate Independence Day 2009, please remember our soldiers and their families who miss them.

By: Rebecca,

on 3/18/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

States,

United,

war,

Politics,

Current Events,

American History,

Iraq,

pakistan,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

middle east,

Afghanistan,

terrorism,

World History,

Middle,

East,

struggle,

United States,

accidental guerrilla,

couterinsurgency,

kilcullen,

Accidental,

Guerrilla,

conflict,

Add a tag

Dr. David Kilcullen is one of the world’s leading experts on guerrilla warfare. He has served in every theater of the “War on Terrorism” since 9/11 as Special Advisor for Counterinsurgency to the Secretary of State  Condoleezza Rice, Senior Counterinsurgency Advisor to General David Petraeus in Iraq, and chief counterterrorism strategist for the U.S. State Department. In his new book, The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars In The Midst of a Big One, Kilcullen takes us on the ground to uncover the face of modern warfare, illuminating both the global challenges and small wars across the world. In the excerpt below we learn why the Afghanistan is so very difficult and so very important in this struggle.

Condoleezza Rice, Senior Counterinsurgency Advisor to General David Petraeus in Iraq, and chief counterterrorism strategist for the U.S. State Department. In his new book, The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars In The Midst of a Big One, Kilcullen takes us on the ground to uncover the face of modern warfare, illuminating both the global challenges and small wars across the world. In the excerpt below we learn why the Afghanistan is so very difficult and so very important in this struggle.

People often speak of “the Iraq War” and the “the war in Afghanistan” as if they were separate conflicts. But was we have seen, Afghanistan is one theater in a larger confrontation with the transnational takfiri terrorism, not a discrete war in itself. Because of commitments elsewhere-principally Iraq-the United States and its allies have chosen to run this campaign as an “economy of force” operation, with a fraction of the effort applied elsewhere. Most of what has happened in Afghanistan results from this, as much as from local factors. Compared to other theaters where I have worked, the war in Afghanistan is being run on a shoestring. The country is about one and a half times the size of Iraq and has a somewhat larger population (32 million, of whom about 6 million are Pashtun males of military age), but to date the United States has resourced it at about 27 percent of the funding given to Iraq, and allocated about 20 percent of the troops deployed in Iraq (29 percent counting allies). In funding terms, counting fiscal year 2008 supplemental budget requests, by 2008 operations in Iraq had cost the United States approximately $608.3 billion over five years, whereas the war in Afghanistan had cost about $162.6 billion over seven years: in terms of overall spending, about 26.7 percent of the cost of Iraq, or a monthly spending rate of about 19.03 percent that of Iraq. In addition to lack of troops and money, certain key resources, including battlefield helicopters, construction and engineering resources, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets, have been critically short.

Resource allocation in itself is not a sign of success-arguably in Iraq we have spent more than we can afford for limited results-but expenditure is a good indicator of government attention. Thus the international community’s failure to allocate adequate resources for Afghanistan bespeaks an episodic strategic inattention, a tendency to focus on Iraq and think about Afghanistan only when it impinges on public opinion in Western countries, NATO alliance politics, global terrorism, or the situation in Pakistan or Iran, while taking ultimate victory in Afghanistan for granted. Two examples spring to mind: the first was when Admiral Michael G. Mullen, chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, remarked in congressional testimony in December 2007 that “in Afghanistan, we do what we can. In Iraq, we do what we must,” implying that Afghan issues by definition play second fiddle to Iraq, receiving resources and attention only as spare capacity allows. The reason for Admiral Mullen’s remark emerges from the second, larger illustration of this syndrome: by invading Iraq in 2003, the United States and its allies opened a second front before finishing the first, and without sufficient resources to prosecute both campaigns effectively. Western leaders committed this strategic error primarily because of overconfidence and a tendency to underestimate the enemy: they appear to have take for granted that the demise of the Taliban, scattered and displaced but not defeated in 2001, was only a matter of time.

These leaders would have done well to remember the words of Sir Olaf Caroe, a famous old hand of the North-West Frontier of British India, ethnographer of the Pashtuns, and last administrator of the frontier province before independence, who wrote in 1958 that “unlike other wars, Afghan wars become serious only when they are over; in British times at least they were apt to produce an after-crop of tribal unrest [and]…constant intrigue among the border tribes.” Entering Afghanistan and capturing its cities is relatively easy; holding the country and securing the population is much, much harder: as the Soviets (with “assistance,” and a degree of post-Vietnam schadenfreude, from Washington) discovered to their cost, like the British, Sikhs, Mughals, Persians, Mongols, and Macedonians before them. In Afghanistan in 2001, as in Iraq in 2003, the invading Western powers confused entry with victory, a point the Russian General Staff lost no time in pointing out. The Taliban movement’s phenomenal resurgence from its nadir of early 2002 underlines this point: the insurgents’ successes seem due as much to inattention and inadequate resourcing on our part as to talent on theirs.

Afghanistan is also a very different campaign from Iraq, though the two conflicts are linked through shared Western political objectives and cooperation between enemy forces. The Iraq campaign is urban, sectarian, primarily internal, and heavily centered on Baghdad. The Afghan campaign is overwhelmingly rural, centered on the Pashtun South and East, with a major external sanctuary in Pakistan and, as of 2008, increasing support for the effort in Afghanistan than for Iraq (though rhetoric often does not translate into action). Afghanistan is seen as a war of necessity, “the good war,” the “real war on terrorism.” This gives the international community greater freedom of action than in Iraq.

Perhaps counterintuitively, events in Afghanistan also have greater proportional impact than those in Iraq, effort there has greater effect than equal effort in Iraq-a brigade (3,000 people) in Afghanistan is worth a division or more (10,000-12,000) in Iraq, in terms of its proportionate effect on the ground. Regardless of the outcome in Iraq, Afghanistan still presents an opportunity for a positive long-term legacy for Western intervention, if it results in an Afghan state capable of effectively responding to its people’s wishes and meeting their needs.

Conversely, although the American population and the international community are inured to negative media reporting about Iraq, they are less used to downbeat reporting about Afghanistan. Most people polled in successive opinion surveys have tended to assume that the Afghan campaign is going reasonably well, hence Taliban successes or sensational attacks in Afghanistan may actually carry greater political weight than equivalent events in Iraq, a campaign that is so unpopular and about which opinion is so polarized that people tent to assume it is going less well than is actually the case.

Thanks to Nathan Whitlock of the Quillblog for this link to an article from the CBC, about Afghani bookseller, Shah Muhammad Rais, who you may remember from The Bookseller of Kabul. I couldn’t find the website, if it’s up yet, but there is contact info here.

NY: Viking, 2006.

ISBN (hardcover) 0670034827 9780670034826

ISBN (paper) 9780143038252

Michael Sedano

An interesting variation in the subtitle of David Oliver Relin’s telling of Greg Mortenson’s story illustrates two ways to sell the book. The hardcover book calls itself “One man’s mission to fight terrorism and build nations-- one school at a time.” The paperback edition titles itself, “One Man's Mission to Promote  Peace . . . One School at a Time.”

Peace . . . One School at a Time.”

The work offers a creative nonfiction account of a mountaineer who stumbles off the Himalayan peak K2 in 1993. Taking a life-threatening wrong path, he stumbles into an unmapped village far from his intended landing. It’s a life-changing error, both for the mountaineer and the villagers who save Mortenson’s life.

During his recuperation in the village, Mortenson observes the village girls conducting school in the open air because they have no teacher nor a structure. He promises to return and build the girls a school. The adventurer’s gratitude takes on missionary zeal and he cannot stop with the one promise, instead devoting his career to building schools for girls across rural Pakistan. By September 11, 2001, Mortenson’s success has led him to Afghanistan, where he runs afoul of the Taliban, opium traders, moujahedeen, and the CIA. Here is the source of the spin given by the hardbound subtitle as the final chapters of the story focus on Mortenson’s experiences in Afghanistan. It’s an inescapable perspective, but the paperback volume’s subtitle about peace more accurately describes the likely outcome of Mortenson’s actions had there been no attack by the U.S., and a workable strategy should our nation choose alternatives to invasion and religious enmity.

The girls and villages benefiting from Mortenson’s work are Muslim. Mortenson is the son of Christian missionaries and not a convert to Islam. While religious schism plays little role in Mortenson’s commitment, it informs the story in surprising ways. The fathers and village men do not oppose education for their girls, yet one conservative cleric declares fatwa on Mortenson’s efforts, preventing building schools in the region. All of Mortenson’s local supporters are Muslim, too, but are powerless to intercede directly on his behalf. Instead, they petition the “supreme leader” of the Shia in northern Pakistan, who not only declares the fatwa inconsistent with Islam, Syed Abbas offers his wholehearted support to Mortenson’s project.

The story of Mortenson’s various projects fills the book with numerous emotional peaks. Dismal stories of government incompetence, generations of neglect, and abject poverty are sure to be depressing. Then, when the reader gets to see villagers hauling heavy loads up steep mountain tracks, followed by frantic construction ahead of winter culminating in the opening of a girl’s school, knowing that these children’s lives have changed forever is sure to bring tears to all but the most cynical eyes.

Three Cups of Tea offers a compendium of intercultural communication. “Dr. Greg,” as Mortenson is known, adapts to local custom. A natural linguist, he becomes proficient enough to earn the honor explained by the title. Mortenson’s second father, Haji Ali, teaches him that the first cup of tea taken with a villager is taken as a stranger and given out of obligation. The next cup is offered for a guest. The third cup makes one a member of the family.

Perhaps guilelessness helps. In one frightening instance, Mortenson disregards a friend’s advice never to travel alone. He finds himself imprisoned by a warlord and seems at risk of being executed. Beheading has not yet reached the news, so Mortenson fears only being shot. He doesn’t speak the captor’s tongue—he is blazing a trail into new territory—and requests a Koran. Having learned the proper manner of ablution from one informant, and how to read the pages from an illiterate, Mortenson makes a favorable impression. Doubtlessly, the captors have checked out Mortenson’s background and they release him.

Mortenson’s good works created a good name for “Dr. Greg.” As he advances into Afghanistan’s northern frontier, he goes in search of the principal commandhan of Badkshan, a man described as tying spies between two jeeps and pulling their bodies apart, the fiercely reputed Sadhar Khan. Alone and lacking any documentation, having sneaked into town hidden under rotting goat hides, Mortenson approaches a jeep of substantial appearing men. In a strange coincidence, or perhaps a bit of fiction has sneaked under the radar here, when Mortenson says he’s looking for Sadhar Khan, the driver says he is Khan! After a few moments explaining why he’s here, Khan shouts, “You’re Dr. Greg!” A couple years earlier, some riders had appeared near the Pakistan border after an eight day ride, beseeching Mortenson’s building a school for their village. Mortenson had promised he’d see what he could do and was in Badkshan looking to keep that promise. The riders were employees of Sadhar Khan, and they had related the story of the schools and water projects Dr. Greg was fomenting.

Three Cups of Tea has won numerous prizes. The CAI, Central Asia Institute, lists them on their website:

Kiriyama Prize - Nonfiction Award, Time Magazine - Asia Book of The Year, Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association - Nonfiction Award, Borders Bookstore - Original Voices Selection, Banff Mountain Festival - Book Award Finalist, Montana Honor Book Award. Throughout the book, however, come allusions to the ultimate prize, the Nobel Peace Prize. Cynics might point to the softcover subtitle as evidence of a campaign to garner that for Mortenson and his CAI. The hagiographic treatment of Dr. Greg’s career might offer support for that view, if not for the actual good that inheres in building schools for girls in the middle of a culture that putatively forbids that type of education.

There may be a segment of reader who would dismiss Three Cups of Tea as one of the “blame America first” crowd. The “fighting terrorism” spin might support that view. For example, as the book draws to a close we see Mortenson meeting Donald Rumsfeld and being fascinated by the man’s expensive and highly polished shoes. Mortenson addresses a military audience at the Pentagon and relates the contradiction between the U.S. war machine and the need for security, telling them:

“these figures might not be exactly right. But as best as I can tell, we’ve launched 114 Tomahawk cruise missiles into Afghanistan so far. Now take the cost of one of those missile tipped with a Raytheon guidance system, which I think is about $840,000. For that much money, you could build dozens of schools that could provide tens of thousands of students with a balanced nonextremist education over the course of a generation. Which do you think will make us more secure?”

Mortenson has his day before the military to no impact, except for a man who offers him unlimited funds to build schools. But Mortenson recognizes his doom would come from any association with the military and he turns down the bribe. Later, he discusses terrorism and security with a Pakistani Major General. They are watching CNN images of civilian casualties in Baghdad. (p. 310)

“Your President Bush has done a wonderful job of uniting one billion Muslims against America for the next two hundred years.”

“Osama had something to do with it, too,” Mortensen said.

“Osama, baah!” Bashir roared. “Osama is not a product of Pakistan or Afghanistan. He is a creation of America. Thanks to America, Osama is in every home. As a military man, I know you can never fight and win against someone who can shoot at you once and then run off and hide while you have to remain eternally on guard. You have to attack the source of your enemy’s strength. In America’s case, that’s not Osama or Saddam or anyone else. The enemy is ignorance.”

To writer David Oliver Relin’s credit, he controls the political spin exemplified here, spinning out just enough politics to contrast with the warmth and love that fill the first two hundred pages of the book. It’s clear why the hardcover came out with the “fighting terrorism” tag, given the closing pages’ focus on the existing conditions Mortenson works under. That he’s continuing the work building schools for girls in Muslim countries—and finding support from religious and ordinary citizens—is truly encouraging. Wouldn’t it be great if some reader in political authority is reading and learning the cultural lessons of this hopeful book?

That’s the final Tuesday of leap year February. La Bloga welcomes your comments and responses to what you read, or don’t read here. And, as we frequently offer, we welcome guest columnists. Let us know by leaving a comment, or email here, that you have something to say.

Ate,

mvs.

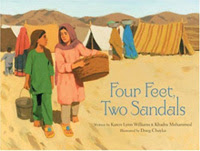

It's hard for children to understand that life for other children around the world can be so different from their own experience. Most American children have a home and clothes and go to school. Four Feet, Two Sandals puts a human face on the refugee crisis around the world. Even though this story focuses on a refugee camp on the Afghanistan/Pakistan border, it is a story that could be placed in any refugee camp.

It's hard for children to understand that life for other children around the world can be so different from their own experience. Most American children have a home and clothes and go to school. Four Feet, Two Sandals puts a human face on the refugee crisis around the world. Even though this story focuses on a refugee camp on the Afghanistan/Pakistan border, it is a story that could be placed in any refugee camp.

This story of friendship found in the most unlikely of places reflects the experience of many refugee children and is, in fact, based on real experiences of the authors. It is a testament to how strong our human need for connection and friendship actually is. When a family is displaced, separated from their home, community, extended family and without a means to support themselves, they become dependent on the kindness of governments and relief organizations. Without control over where they will be relocated, some refugees can live in camps for years.

To realize that friendship can spark and live in a place of such uncertainty and fear is a powerful story of hope and survival. And one which all children should learn about and understand. No matter how bad our situation is, we always have a choice about how to respond to others. We choose whether to stand together or apart.

Refugee camps have some similarity to real life as there are always the routines of every day life that need to be created. Gathering water, washing clothes, cooking food, and care of the family. Impermanance, insecurity and fear fuels the concerns and conversation of everyone living in a camp. Caught between an old life that is gone forever and a new life that cannot yet be glimpsed is frightening.

Yet in the midst of that, two girls find each other and share a pair of shoes. Their friendship helps them humanize their situation reminding them that there are still wonderful things that life will offer them. Illustrator Doug Chayka uses soft, warm colors to convey the desert, tents, primitive conditions, and clothing of the people in the camp.

This is a wonderful story of friendship and hope that should be shared as widely as possible. When we know the face of the "other", we are more likely to greet them as friends than as enemies.

By:

Donna J. Shepherd,

on 12/13/2007

Blog:

Topsy Turvy Land - Donna J. Shepherd

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Children's,

Kevin Scott Collier,

Teeth,

coloring page,

Gunk,

Kevin Scott Collier,

coloring page,

Gunk,

Teeth,

Add a tag

Illustrator of Topsy Turvy Land (Hidden Pictures Publishing), Kevin Scott Collier, sent a cute coloring page for No More Gunk! Thanks, Kevin!

Click HERE to download and color. I'd love it if some of you parents would scan your child's masterpiece and send me the finished page, I'll post them!

______

.jpg?picon=380)

By:

Just One More Book!!,

on 12/6/2007

Blog:

Just One More Book Children's Book Podcast

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

review,

Podcast,

Community,

Family,

Ages 4-8,

Formal,

Compassion,

Creativity,

Fairy tales and legends,

Picture book,

Friendship,

Appreciation,

childrens book,

Fun,

Animal,

Life Skills,

Freedom,

Hilarious,

Humour,

Man,

Thinking/Attitude,

India,

Understanding/Tolerance,

Communication,

Fairness / Justice,

afghanistan,

Ande Cook,

Rumi,

Suzan Nadimi,

The Rich Man and the Parrot,

afghanistan,

Fairness / Justice,

Ande Cook,

Rumi,

Suzan Nadimi,

The Rich Man and the Parrot,

Add a tag

Author: Suzan Nadimi

Author: Suzan Nadimi

Illustrator: Ande Cook

Published: 2007 Albert Whitman & Co. (on JOMB)

ISBN: 0807550590 Amazon.ca Amazon.com

Lyrical dialog and sweet, somehow soothing illustrations bring to life an 800 year old story of fondness and freedom that challenges us to make space for the perspectives of both captor and captive.

Other books mentioned:

You can read more about thirteenth century mystic poet Mawlana Jalal ad-Din Rumi and the designation of 2007 by UNESCO as the International Year of Rumi here.

Tags:

afghanistan,

Ande Cook,

childrens book,

India,

Podcast,

review,

Rumi,

Suzan Nadimi,

The Rich Man and the Parrotafghanistan,

Ande Cook,

childrens book,

India,

Podcast,

review,

Rumi,

Suzan Nadimi,

The Rich Man and the Parrot

This is my first post for Monday Artday.

This is my first post for Monday Artday.

My title for it is:

'Brush your teeth twice a day'

Or maybe it should be:

'Brush your two teeth every day'

By: Stacy Dillon,

on 11/8/2007

Blog:

Welcome to my Tweendom

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

military,

Afghanistan,

Afghanistan,

Tween,

Afghanistan,

sisters,

Friendship,

sisters,

Tween,

military,

Add a tag

Have you ever made one of those lists? You know, the ones that will get you kicked out of school these days?

Sprig is working on one about her sister Dakota. Sprig and Dakota used to get along, but now Dakota thinks that since she is older, she has all of the answers. Just because Sprig is quick to tears, and misses her dad more than anything when he goes away on business, doesn't mean that she is the baby in the family.

Now dad is talking about going to Afghanistan! Sprig knows that he is going for a very good reason (to build schools for girls) but she has looked online, and it's dangerous over there!

And school is getting confusing too. Sprig's best friend Bliss keeps siding with big old Russell, who Sprig thinks is nothing more than a bully. Are Bliss and Russell becoming more than friends? To top it all off, Sprig's teacher is off on maternity leave and Mr. Julius is subbing. Nothing is like it was!

Norma Fox Mazer has written a story about growing pains, and change. Kids with family in the military will appreciate her references to those in service, without making the whole book about the war. Sprig is learning that wishing Dakota away may not be the answers to her problems. After all, during rough times, sisters end up needing each other.

View Next 1 Posts

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism (recommended by bin Laden himself). His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden which he recently discussed on The Colbert Report (and this podcast!).

Michael Scheuer was the chief of the CIA’s bin Laden unit from 1996 to 1999 and remained a counterterrorism analyst until 2004. He is the author of many books, including the bestselling Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terrorism (recommended by bin Laden himself). His latest book is the biography Osama bin Laden which he recently discussed on The Colbert Report (and this podcast!).

A young Afghan boy shares his life and dreams for the future with us in The Roses in My Carpets by Rukhsana Khan and illustrated by Ronald Himler (Holiday House, 1998), a beautiful, thought-provoking picture book set in a refugee camp in Pakistan. He doesn’t like school but loves the afternoons he spends weaving carpets from brightly colored threads that all hold special meaning for him: although “Everything in the camp is a dirty brown, so I do not use brown anywhere on my carpets.” One day his work is interrupted by the shocking news that his sister has been badly hurt. He runs to the hospital. His mother is already there, too distraught to think rationally. Our young narrator takes charge, sending his mother home while he waits for news at the hospital. Fortunately, this being a children’s story, the news is good – which in turn allows for a breathing space that alters the nightmare of conflict he describes at the beginning of the book: that night his dreams open up to allow a tiny space out of danger for him and his beloved family.

A young Afghan boy shares his life and dreams for the future with us in The Roses in My Carpets by Rukhsana Khan and illustrated by Ronald Himler (Holiday House, 1998), a beautiful, thought-provoking picture book set in a refugee camp in Pakistan. He doesn’t like school but loves the afternoons he spends weaving carpets from brightly colored threads that all hold special meaning for him: although “Everything in the camp is a dirty brown, so I do not use brown anywhere on my carpets.” One day his work is interrupted by the shocking news that his sister has been badly hurt. He runs to the hospital. His mother is already there, too distraught to think rationally. Our young narrator takes charge, sending his mother home while he waits for news at the hospital. Fortunately, this being a children’s story, the news is good – which in turn allows for a breathing space that alters the nightmare of conflict he describes at the beginning of the book: that night his dreams open up to allow a tiny space out of danger for him and his beloved family.

author of more than 30 books he is an honorary life member of the

author of more than 30 books he is an honorary life member of the

Author:

Author:

I am actually booktalking this one to our sixth through eighth grade book group today. I was also really impressed with his nuanced portrayal of the situation in Afghanistan and the fact that the information that he gave was such a natural part of the story. I think you’re right, too, that kids will gloss over some of the stuff that they don’t understand. I know I did when I read THE GODFATHER when I was twelve!

When I first heard about this book I thought, wow sounds exactly like Wanting Mor. BUT I found wanting Mor a bit…wanting. It briefly touches on important issues but never fully dives into them and it seems that Words in the Dust does. Wanting Mor mentions that the Afghans are tired of being treated like charity cases but it doesn’t go further than that. i like that Words in the Dust not only brings that issue up but shows the complicated situation in Afghanistan with the soldiers.

And yes people need to realize that not every single person in Afghanistan supports the Taliban. Good grief. That’s why I’m grateful to books like this one

Excellent review, you made me even more eager to run out and get this book!