new posts in all blogs

Viewing Blog: The Mumpsimus, Most Recent at Top

Results 26 - 50 of 1,133

A blog about "displaced thoughts on misplaced literatures."

Matthew Cheney is a writer and teacher who lives in New Hampshire. His work has been published by English Journal, Strange Horizons, Failbetter.com, Ideomancer, Pindeldyboz, Rain Taxi, Locus, The Internet Review of Science Fiction and SF Site, among other places.

Statistics for The Mumpsimus

Number of Readers that added this blog to their MyJacketFlap: 4

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 3/28/2016

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

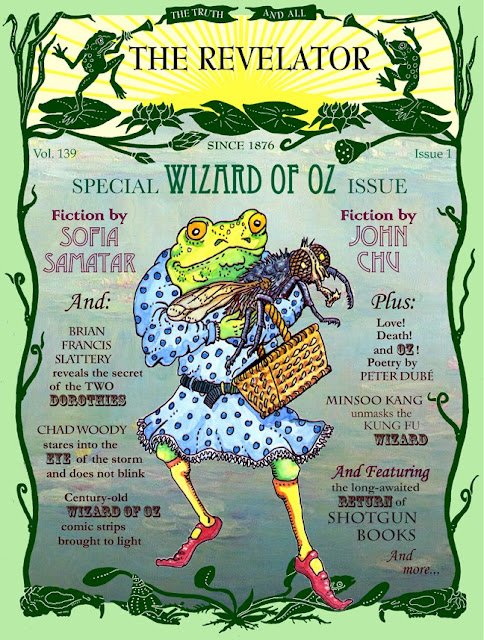

Once again, chaos and luck have conspired to release another issue of the venerable

Revelator magazine into the world!

In this issue, you can read new fiction by Sofia Samatar and John Chu; an excursion into musical history by Brian Francis Slattery; surreal prose poems by Peter Dubé; an essay by Minsoo Kang; revelatory, rare, and historical

Wizard of Oz comics; art by Chad Woody; and, among other esoterica, shotgunned books!

Go forth now, my friends, and revel in The Truth ... and All!

This review originally appeared in the January 2006 issue of

Z Magazine. I'd forgotten about it until somebody today mentioned that it's the anniversary of most of the striking workers' demands being met (12 March 1912), and so today seemed like a good one to post this:

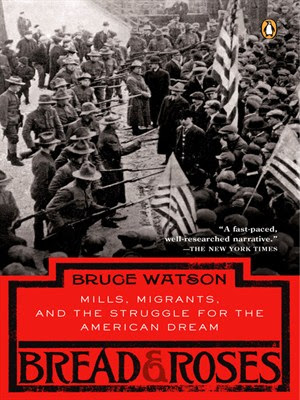

by Bruce Watson

New York, Viking, 2005, 337 pp.

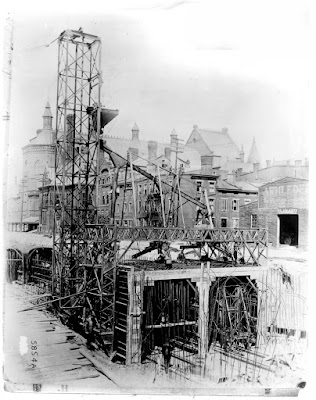

Lawrence, Massachusetts was, at the beginning of the twentieth century, what might be called one of the greatest mill towns in the United States, but "greatest" is a difficult term, and underneath it hide all the conditions that erupted during the frigid winter of 1912 into a strike that affected both the labor movement and the textile industry for decades afterward.

Bruce Watson's compelling and deeply researched chronicle of the strike takes its name from a poem and song that have come to be associated with Lawrence, although there is, according to Watson, no evidence that "Bread and Roses" ever appeared as a slogan in Lawrence until long after 1912. This fact might suggest that Watson's position is one of a debunker, but he offers less debunking than revitalizing, and the ultimate effect of his book is to show why the romantic notions behind the "Bread and Roses" phrase do a disservice to the courage and accomplishments of the strikers.

Watson's greatest strength is his ability to weave weighty research into a narrative that is lively and seldom ponderous.

There are costs to this approach, because the minutia of a strike's planning and execution are not always suspenseful, and so, as Watson strives to hold the reader's interest there are times when the sentences sound like the narration of "America's Most Wanted" and swaths of yellow from the journalism of 1912 seem to have seeped into the book's pages.

This is a minor annoyance, though, in a book filled with vivid portraits of ordinary workers and their families, and with precise, careful renderings of an age and culture.

Again and again, Watson brings the book back to the circumstances of the immigrant workers who started the strike, and he compares their lives to those of other workers throughout the United States, to the owners and administrators of the mills, to the politicians, to the police and the soldiers who were sometimes fierce combatants with the strikers, sometimes bewildered and beleaguered sympathizers.

It would be interesting to watch a free-market ideologue respond to Bread and Roses, because again and again Watson presents damning evidence of the failures of unbridled capitalism to produce anything but misery for people who worked in the mills. He includes a budget created by one of the workers' wives; she lists such expenses as rent, kerosene, milk, bread, and meat. Watson lays out the family's other expenses, the fact that they couldn't afford to buy coal and so their only heat during the brutal winters came from the bits of wood their children could scavenge, the luxuries they couldn't buy (butter and eggs), and then comments: "Like most mill workers, the Bleskys could not afford clothes fashioned in Manhattan sweatshops from fabric made in Lawrence. ... The Bleskys each wore the same clothes until they wore out. When the strike began, Mrs. Blesky was still wearing the shawl, skirt, and shirtwaist she had bought in Poland three years earlier, just before coming to Lawrence. Ashamed of her shabby appearance, she almost never left her home."

Searching through numerous archives, Watson has unearthed one story after another like this one, and each undermines the fanciful justifications and accusations made by the mill owners, which Watson also chronicles well. To his credit, though, he does not present the owners, the politicians who supported them, and the reporters who often printed even their most outrageous lies as caricatures, creatures so obsessed with profit that they would happily trod over the people who created that profit for them. Instead, he tries to divine the self-delusions and paranoid fears that motivated the workers' many antagonists. While on the surface it may seem immoral to try to portray the masters of such misery as flawed and idealistic human beings, the result is both complex and useful, because ideology was as much a part of what created the misery as was greed.

The Lawrence strike became a national cause, and it attracted the attention of celebrities and rising stars of the labor movement, including Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn of the IWW and John Golden of the AF of L. The events and tactics that brought so much attention to Lawrence are particularly fascinating, and Watson does an admirable job of showing how the strikers decided to carry out the strike and advance their cause, particularly with the controversial and immensely effective "children's exodus", where the children of strikers were sent to the homes of union members in New York, Vermont, and elsewhere. With each new day and week of the strike, more groups joined in, until the strike itself became, for a short time, a panoply of people from all around the world. Numerous women, too, who had often been relegated to the background in labor struggles before, became vital players in Lawrence, and the book includes a marvelous photograph of a parade of women holding their hands high, joyous smiles on their faces as they march down the street, defying the martial law imposed on the city.

Even as more and more strands are added to the story, the tale itself stays clear. Watson manages to show how the different segments of the labor movement both aided and undermined each other, and he doesn't smooth over the conflicts that broke out when the national interests were different from the local ones. (On the whole, though, this strike was remarkably unified compared to others both before and after it.) Haywood and Flynn in particular make for great characters in the story, but Watson skillfully keeps them from stealing the stage, always bringing the story back to the lives of the workers in Lawrence, the people who would have to live with the consequences of the strike once the nation's interest turned to other events.

In the end, it is the ordinary workers who remain the most remarkable element of the Lawrence strike, as Watson tells the story, because here were people from vastly different backgrounds, experiences, religions, and even political views who found solidarity and, through this solidarity, a certain amount of success.

The epilogue is not misty-eyed about the effects and consequences of the strike, but it also offers a kind of quiet hope for the future: for all the possibilities that imaginative, energetic, and compassionate mass action can create.

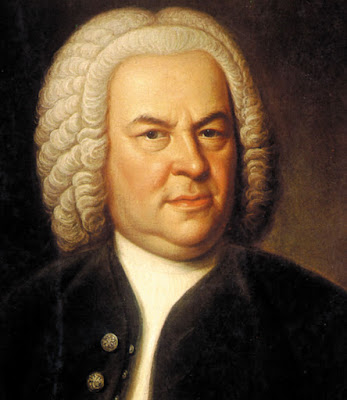

John Eliot Gardiner, from

Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven (Preface):

A nagging suspicion grows that many writers, overawed and dazzled by Bach, still tacitly assume a direct correlation between his immense genius and his stature as a person. At best this can make them unusually tolerant of his faults, which are there for all to see: a certain tetchiness, contrariness and self importance, timidity in meeting intellectual challenges, and a fawning attitude toward royal personages and to authority in general that mixes suspicion with gain-seeking. But why should it be assumed that great music emanates from a great human being? Music may inspire and uplift us, but it does not have to be the manifestation of an inspiring (as opposed to an inspired) individual. In some cases there may be such correspondence, but we are not obliged to presume that it is so. It is very possible that "the teller may be so much slighter or less attractive than the tale." [source] The very fact that Bach's music was conceived and organized with the brilliance of a great mind does not directly give us any clues as to his personality. Indeed, knowledge of the one can lead to a misplaced knowingness about the other. At least with him there is not the slightest risk, as with so many of the great Romantics (Byron, Berlioz, Heine spring to mind), that we might discover almost too much about him or, as in the case of Richard Wagner, be led to an uncomfortable correlation between the creative and the pathological.

Eric Bennett has an MFA from

Iowa, the MFA of MFAs. (He also has a Ph.D. in Lit from Harvard, so he is a man of fine and rare academic pedigree.) Bennett's recent book

Workshops of Empire: Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing during the Cold War is largely about the Writers' Workshop at Iowa from roughly 1945 to the early 1980s or so. It melds, often explicitly,

The Cultural Cold War with

The Program Era, adding some archival research as well as Bennett's own feeling that the work of politically committed writers such as Dreiser, Dos Passos, and Steinbeck was marginalized and forgotten by the writing workshop hegemony in favor of individualistic, apolitical writing.

I don't share Bennett's apparent taste in fiction (he seems to consider Dreiser, Dos Passos, Steinbeck, Thomas Wolfe, etc. great writers; I don't), but I sympathize with his sense of some writing workshops' powerful, narrowing effect on American fiction and publishing for at least a few decades. He notes in his conclusion that the hegemonic effect of Iowa and other prominent programs seems to have declined over the last 15 years or so, that Iowa in recent years has certainly become more open to various types of writing, and that even when Iowa's influence was at an apex, there were always other sorts of programs and writers out there — John Barth at Johns Hopkins, Robert Coover at Brown, and Donald Barthelme at the University of Texas are three he mentions, but even that list shows how narrow in other ways the writing programs were for so long: three white hetero guys with significant access to the NY publishing world.

What Bennett most convincingly shows is how the discourse of creative writing within U.S. universities from the beginning of the Cold War through at least to the 1990s created a field of limited, narrow values not only for what constitutes "good writing", but also for what constitutes "a good writer". It's a tale of parallel, and sometimes converging, aesthetics, politics, and pedagogies. Plenty of individual writers and teachers rejected or rebelled against this discourse, but for a long time it did what hegemonies do: it constructed common sense. (That common sense was not only in the workshops — at least some of it made its way out through writing handbooks, and can be seen to this day in pretty much all of the popular handbooks on how to write, including Stephen King's

On Writing.)

Some of the best material in

Workshops of Empire is not its Cold War revelations (most of which are known from previous scholarship) but in its careful limning of the tight connections between particular, now often forgotten, ideas from before the Cold War era and what became acceptable as "good writing" later. The first chapter, on the

"New Humanism", is revelatory, especially in how it draws a genealogy from

Irving Babbitt to Norman Foerster to

Paul Engle and

Wallace Stegner. Bennett tells the story of New Humanism as it relates to New Criticism and subsequently not just the development of workshop aesthetics, but of university English departments in the second half of the 20th century generally, with New Humanism adding a concern for ethical propriety ("the question of the relation of the goodness of the writing to the goodness of the writer") to New Criticism's cold formalism:

Whereas the New Criticism insisted on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the poem or story — every word counted — the New Humanism focused its attention on the irreducible and indivisible integrity of the humanistic subject. It did so not as a kind of progressive-educational indulgence but in deference to the wholeness of the human person and accompanied by a strict sense of good conduct. (29-30)

This mix was especially appealing to the post-WWII world of anti-Communist liberalism, a world scarred by the horrors of Nazism and Stalinism, and a United States newly poised to inflict its empire of moral righteousness across the world.

For all of Bennett's gestures toward Marxism and anti-imperialism, he seems to share some basic assumptions about the power of literature with the men of the Cold War era he disdains as conservatives. In the book's conclusion, he writes:

It remains an open question just how much criticism some or all American MFA programs deserve for contributing to the impasse of neoliberalism — the collective American disinclination to think outside narrow ideological commitments that exacerbate — or at the very least preempt resistance to — the ugliest aspects of the global economy. Those narrow commitments center, above all, on an individualism, economic and otherwise, vastly more powerful in theory and public rhetoric than in fact. We encourage ourselves to believe that we matter more than we do and to go it alone more than we can. This unquestioned inflation of the personal begs, in my opinion, the kinds of questions that must be asked before any reform or solution to some seriously pressing problems looks likely to be found. (173)

This is almost comically self-important in its idea that MFA programs might (he hopes?) have enough cultural effect that if only they had been more willing to teach students to write like Thomas Wolfe and John Steinbeck, then maybe we could conquer neoliberalism! One moderately popular movie has more cultural effect than piles and piles of books written by even the famous MFA people. If you want to fight neoliberalism, your MFA and your PhD (from Harvard!) aren't likely to do anything, sorry to say. If you want to fight neoliberalism ... well, I don't know. I'm not convinced neoliberalism

can be fought, though we might be able to find

an occasional escape in aesthetics. The idea that Books Do Big Things In The World is one that Bennett shares with his subjects; he'd just prefer they read different books.

As self-justifying delusions go, I suppose there are worse, and all of us who spend our lives amidst writing and reading believe to some extent or another that it's worthwhile, or else we wouldn't do it. But "worthwhile" is far from "world-changing". (Rx: Take a couple

Wallace Shawn plays and call me in the morning.)

Despite this, Bennett's concluding chapter had me raising my fist in solidarity, because no matter what our personal tastes in fiction may be, no matter how much we may disagree about the extent to which writing can influence the world, we agree that writing pedagogy ought to be diverse and historically informed in its approach.

Bennett shows some of the forces that imposed a common shallowness:

There was, in the second wave of programs — the nearly fifty of them founded in the 1960s — little need to critique the canon and smash the icons. To the contrary, the new roster of writing programs could thrive in easy conscience. This was because each new seminar undertook to add to the canon by becoming the canon. The towering greats (Shakespeare, Milton, Whitman, Woolf, whoever) diminished in influence with each passing year, sharing ever more the icon's niche with contemporary writers. In 1945, in 1950, in 1955, prospective poets and novelists looked to the neverable pantheon as their competition. In 1980, in 1990, in 2015, they more often regarded their published teachers or peers as such. (132)

That's polemical, and as such likely hyperbolic, but it suggests some of the ways that some writing programs may have capitalized on the culture of narcissism that has only accelerated via social media and

is now ripe for economic exploitation. I don't think it's a crisis of the canon — moral panics over the Great Western Tradition are academic Trumpism — so much as a crisis of literary-historical knowledge. Aspiring writers who are uninterested in reading anything written before they were born are nincompoops. Understandably and forgiveably so, perhaps (U.S. culture is all about the current whizbang thing, and historical amnesia is central to the American project), but too much writing workshop pedagogy, at least of the recent past, has been geared toward encouraging nincompoopness. As Bennett suggests, this serves the interests of American empire while also serving the interests of the writing world. It domesticates writers and makes them good citizens of the nationalistic endeavor.

Within the context of the book, Bennett's generalizations are mostly earned. What was for me the most exciting chapter shows exactly the process of simplification and erasure he's talking about. That chapter is the final one before the conclusion: "Canonical Bedfellows: Ernest Hemingway and Henry James". Bennett's claim here is straightforward: The consensus for what makes writing "good" that held at least from the late 1940s to the end of the 20th century in typical writing workshops and the most popular writing handbooks was based on teachers' knowledge of Henry James's writing practices and everyone's veneration of Hemingway's stories and novels.

For Bennett, Hemingway became central to early creative writing pedagogy and ideology for three basic reasons: "he fused together a rebellious existential posture with a disciplined relationship to language, helping to reconcile the avant-garde impulse with the classroom", "he offered in his own writing...a set of practices with the luster of high art but the simplicity of any good heuristic", and "he contributed a fictional vision whose philosophical dimensions suited the postwar imperative to purge abstractions from literature" (144). Hemingway popularized and made accessible many of the innovations of more difficult or esoteric writers: a bit of Pound from Pound's Imagist phase, some of Stein's rhythms and diction, Sherwood Anderson's tone, some of the early Joyce's approach to word patterns... ("He was possibly the most derivative

sui generis author ever to write," Bennett says. Snap!) Hemingway's lifestyle was at least as alluring for post-WWII male writers and writing teachers as his writing style: he was macho, war-scarred, nature-besotted in a Romantic but also carnivorous way. He was no effete intellectual. If you go to school, man, go to school with Papa and you'll stay a man.

The effect was galvanizing and long-term:

Stegner believed that no "course in creative writing, whether self administered or offered by a school, could propose a better set of exercises" than this method of Hemingway's. Aspirants through to the present day have adopted Hemingway's manner on the page and in life. One can stop writing mid-sentence in order to return with momentum the following morning; aim to make one's stories the tips of icebergs; and refrain from drinking while writing but aim to drink a lot when not writing and sometimes in fact drink while writing as one suspects with good reason that Hemingway himself did, despite saying he didn't. One can cultivate a world-class bullshit detector, as Hemingway urged. One can eschew adverbs at the drop of a hat. These remain workshop mantras in the twenty-first century. (148)

Clinching the deal, the Hemingway aesthetic allowed writing to be gradeable, and thus helped workshops proliferate:

Hemingway's methods are readily hospitable to group application and communal judgment. A great challenge for the creative writing classroom is how to regulate an activity ... whose premise is the validity and importance of subjective accounts of experience. The notion of personal accuracy has to remain provisionally supreme. On what grounds does a teacher correct student choices? Hemingway offered an answer, taking prose style in a publicly comprehensible direction, one subject to analysis, judgment, and replication. ... One classmate can point to metaphors drawn from a reality too distant from the characters' worldview. Another can strike out those adverbs. (151)

Bennett then points out that the predecessors of the New Critics, the conservative Southern Agrarians, thought they'd found in Hemingway almost their ideal novelist (alas, he wasn't Southern). "The reactionary view of Hemingway," Bennett writes, "became the consensus orthodoxy." Hemingway's concrete details don't offer clear messages, and thus they allowed his work to be "universal" — and universalism was the ultimate goal not only of the Southern Agrarians, but of so many conservatives and liberals after WWII, when art and literature were seen as a means of uniting the world and thus defeating Communism and U.S. enemies. "Universal" didn't mean

actually universal in some equal exchange of ideas and beliefs — it meant imposing American ideals, expectations, and dreams across the globe. (And consequently opening up the world to American business.)

Such a discussion of how Hemingway influenced creative writing programs made me think of other ways complex writing was made appealing to broad audiences — for instance, much of what Bennett writes parallels with some of the ideas in work such as

Creating Faulkner's Reputation by Lawrence H. Schwartz and especially

William Faulkner: The Making of a Modernist, where Daniel Singal

proposes that Faulkner's alcoholism, and one alcohol-induced health crisis in November 1940 especially, turned the last 20 years of Faulkner's life and writing into not only a shadow of its former achievement, but a mirror of the (often conservative) critical consensus that built up around him through the 1940s. Faulkner became teachable, acceptable, "universal" in the eyes of even conservative critics, as well as in Faulkner's own pickled mind, which his famous

Nobel Prize banquet speech so perfectly shows.

(Thus some of my hesitation around Bennett's too easy use of the word "modernist" throughout

Workshop of Empire — the strain of Modernism he's talking about is a sanitized, domesticated, popularized, easy-listening Modernism. It's Hemingway, not Stein. It's late Faulkner, not

Absalom, Absalom!. It's white, macho-male, heterosexual, apolitical. The influence seems clear, but it chafes against my love of a broader, weirder Modernism to see it labeled only as "modernism" generally.)

Then there's Henry James. Not for the students, but the teachers:

As with Hemingway, James performed both an inner and an outer function for the discipline. In his prefaces and other essays, he established theories of modern fiction that legitimated its status as a discipline worthy of the university. Yet in his powers of parsing reality infinitesimally, James became an emblem similar to Hemingway, a practitioner of resolutely anti-Marxian fiction in an era starved for the same. (152)

Reducing the influence and appeal here to simply the anti-Marxian is a tic produced by Bennett's yearning for the return of the Popular Front, because his own evidence shows that the immense influence of Hemingway and James served not only to veer teachers, students, writers, and critics away from any whiff of agit-prop, but that it created an aesthetic not only hostile to Upton Sinclair but to the 19th century Decadents and Symbolists, to much of the Harlem Rennaissance, to most forms of popular literature, and to any writers who might seem too difficult, abstruse, or weird (imagine Samuel Beckett in a typical writing workshop!).

As Bennett makes clear, the

idea of Henry James's writing practice more than any of James's actual texts is what held through the decades. "He did at least five things for the discipline," Bennett says (152-153):

- His Prefaces assert the supremacy of the author, and "the early MFA programs depended above all on a faith that literary meaning could be stable and stabilized; that the author controlled the literary text, guaranteed its significance, and mastered the reader."

- James's approach was one of research and selection, which is highly appealing to research universities. Writing becomes a laboratory, the writer an experimenter who experiments succeed when the proper elements are selected and balanced. "He identified 'selection' as the major undertaking of the artist and perceived in the world a landscape without boundaries from which to do the selecting." Revision is key to the experiment, and revision should be limitless. Revision is virtue.

- James was anti-Romantic in a particular way: "James centered modern fiction on art rather than the artist, helping to shape the doctrines of impersonality so important to criticism from the 1920s through the 1950s. He insulated the aesthetic object from the deleterious encroachments of ego." Thus the object can be critiqued in the workshop, not the creator.

- "James nonetheless kept alive the romantic spirit of creative inspiration and drew a line between those who have it and those who don't." He often sounds mystical in his Prefaces (less so his Notebooks). The craft of writing can be taught, but the art of writing is the realm of genius.

- "James regarded writing as a profession and theorized it as one." The writer is someone who labors over material, and the integrity of the writer is equal to the integrity of the process, which leads to the integrity of the final text.

These ideas took hold and were replicated, passed down not only through workshops, but through numerous handbooks written for aspiring writers.

The effect, ultimately, Bennett asserts, was to stigmatize intellect. Writing must not be a process of thought, but a process of feeling. It must be sensory. "No ideas but in things!" A convenient ideology for times of political turmoil, certainly.

Semester after semester, handbook after handbook, professor after professor, the workshops were where, in the university, the senses were given pride of place, and this began as an ideological imperative. The emphasis on particularity, which remains ubiquitous today, inviolable as common sense, was a matter for debate as recently as 1935. The debate, in the 21st century, is largely over. (171)

I wonder. From writers and students I sense — and this is anecdotal, personal, sensory! — a desire for something more than the old Imagist ways. A desire for thought in fiction. For politics, but not a simple politics of vulgar Marxism. The ubiquity of dystopian fiction signals some of that, perhaps. Dystopian fiction is being written by both the hackiest of hacks and the highest of high lit folks. It shows a desire for imagination, but a particular sort of imagination: an imagination about society. Even at its most

personal, navel-gazing, comforting, and self-justifying, it's still at least trying to wrestle with more than the concrete, more than the story-iceberg.

So, too, the efflorescence of different types of writing programs and different types of teachers throughout the U.S. today suggests that the era of the aesthetic Bennett describes may be, if not over, at least far less hegemonic. Bennett cites its apex as somewhere around 1985, and that seems right to me. (I might bump it to 1988: the last full year of Reagan's presidency and the publication of Raymond Carver's selected stories,

Where I'm Calling From.) The people who graduated from the prestigious programs then went on to become the administrators later, but at this point most of them have retired or are close to retirement. There are still

narrow aesthetics, but there's plenty else going on. Most importantly, writers with quite different backgrounds from the old guard are becoming not just the teachers, but the administrators. Bennett notes that some of the criticism he received for

earlier versions of his ideas pointed to these changes:

I was especially convinced by the testimony of those who argued that the Iowa Writers' Workshop under Lan Samantha Chang's directorship has different from Frank Conroy's iteration of that program, which I attended in the late 1990s and whose atmosphere planted in my heart the suspicion that, for some reason, the field of artistic possibilities was being narrowed exactly where it should be broadest. In the twenty-first century, things have changed both at Iowa and at the many programs beyond Iowa, where few or none of my conclusions might have pertained in the first place. (163)

That's an important caveat there. The present is not the past, but the past contributed to the present, and it's a past that we're only now starting to recover.

There's much more to be investigated, as I'm sure Bennett knows. The role of the

Bread Loaf Writers' Conference and similar institutions would add some more detail to the study; similarly, I think someone needs to write about the intersections of creative writing programs and composition/rhetoric programs in the second half of the twentieth century. (Much more needs to be written about CUNY during

Mina Shaughnessy's time there, for instance, or about

Teachers & Writers.) But the value of Bennett's book is that it shows us that many of the ideas about what makes writing (and writers) "good" can be — should be — historicized. Such ideas aren't timeless and universal, and they didn't come from nowhere. Bennett provides a map to some of the wheres from whence they came.

|

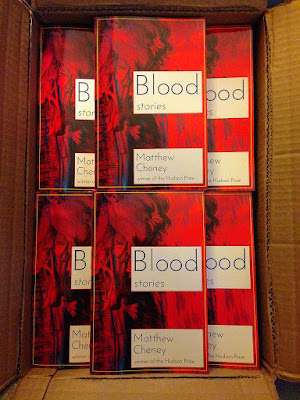

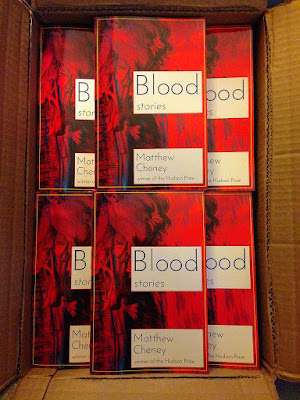

| a box of Blood |

Though delayed, my debut collection,

Blood: Stories, now exists. I know because I received copies of it straight from the printer. That means it's also going to arrive at the distributor within the next day or so, and from there ... out into the world.

I'll have plenty more to say later, I'm sure. For now, I'm just going to go marvel at the thing itself...

Read the rest of this post

Posting here is likely to continue to be sparse for a while, aside from occasional announcement-type notes such as this one. I'm preparing for Ph.D. qualifying exams and anything not related to that and/or to the impending release of

Blood: Stories has been cut from my waking hours since this summer.

Blood: Stories has an official release date of February 20. It is at the printer now as I write this, and can be ordered not only from the publisher, but also from

Amazon (U.S.),

Barnes & Noble, and

Small Press Distribution. (It hasn't hit Book Depository yet, but when/if it does, I'll post a link, as that's often the least expensive way to order internationally.) There will be an e-book version eventually, but not until this summer at the earliest. BLP also has

a new subscription series for their books, which has various options, all of which are less expensive than buying the books individually.

I'll be in New York City this coming weekend

to read at the Sunday Salon series on February 21 at Jimmy's No. 43 (43 E. 7th St.) at 7pm alongside Alison Kinney, Thaddeus Rutkowski, and Terese Svoboda. If you're in the area, stop by!

Various other events are coming up, too. I'll mention them here, but you can also keep up with things via

Twitter, my

newsletter, and/or

the book's Facebook page.

Speaking of books, Eric Schaller's debut story collection,

Meet Me in the Middle of the Air, has now been released by Undertow Publications (and is available as both a bookbook and an e-book at the usual outlets). It's a marvelous concatenation of stories of horror, dark fantasy, and general weirdness. Some are disturbing, some are amusing, some are both. It's a really smart, entertaining book. I'm especially pleased it's coming out now, near to the release of my own collection, because Eric has been my erstwhile partner in a number of crimes, including

The Revelator (a new issue of which is impending. Even more than its been impending before). Eric hasn't always gotten the credit he deserves as fiction writer because he only publishes stories now and then, and often in somewhat esoteric places, so it's a real pleasure and even a (dare I say it?)

revelation to have a whole book of his work and to get to see the range and complexity of his writing.

Finally, in terms of new work, I have exciting news (well, exciting to me) -- my story "Mass" will appear in the next print issue (issue 66) of

Conjunctions. It's a tale of academia, mass shootings, and theoretical physics. Having it published by

Conjunctions is almost as exciting for me as having a book out, because

Conjunctions is my favorite literary journal, the place where the aesthetic feels most convivial to my own, and I've been submitting to it for almost 20 years. I've had stories on the website twice (

"The Art of Comedy" and

"The Last Vanishing Man"), and numerous stories that came close, but were not quite right for the theme of the issue or didn't quite fit with other material or just weren't quite to the editors' tastes. Getting into the pages of

Conjunctions means more to me than getting into

The New Yorker or any other magazine would (although I'd love the

New Yorker paycheck!).

I think that's it for news. Thanks for reading, and thanks for bearing with me!

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 1/29/2016

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Add a tag

We're almost there — my debut book,

Blood: Stories, was scheduled for January release, but is going to be a couple weeks late, because things happen, it's a small press, etc. It looks like it's going to be a really beautiful object and well worth the wait. I expect copies will be making their way out in the world around the second week of February.

The book's info has been submitted to the distributor (

Small Press Distribution), and should appear in their databases early next week, which will allow bookstores and libraries to place orders. It should also be hitting all the online vendors soon. (It's been on

Goodreads for a while.) That means

the pre-order sale from Black Lawrence Press will end, so if you want to order directly from the publisher at a discount, you'll need to do it immediately to get the discount.

People have asked about e-books. BLP does not yet do e-books, though they're hoping to have them by the end of the year. Plans are afoot. But I doubt there will be any before summer at the earliest.

I'll be stepping out of my hermitage and making some appearances to support the book. The first will be

Sunday Salon in New York City on February 21. Then I'll be at the

AWP Conference in Los Angeles (March 30-April 2), where I'm doing a couple of signings and a reading. This summer, I'll be at

Readercon. More details on all of this later. My

newsletter and/or

Twitter are good ways to keep up with what I'm up to.

(Reviewers: Either BLP or I can provide a PDF, an unofficial e-book, or, if you're really convincing about your need for it, a physical copy [they're a small press with limited resources, and hardcopies are not cheap even for the publisher]. Email

me or

[email protected].)

And here is the table of contents:

“How to Play with Dolls”

Weird Tales, no. 352, November/December 2008

“Blood”

One Story, no. 81, 2006

“Revelations”

Sunday Salon, November 2009

“Getting a Date for Amelia”

Failbetter, no 4, 2001

“The Lake”

Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, no. 21, November 2007

“Lonesome Road”

Icarus, Winter 2010.

“Prague”

Ideomancer, 2004

“In Exile”

Mythic, edited by Mike Allen. Mythic Delirium Books, 2006

“How Far to Englishman’s Bay”

Nightmare, August 2013

“The Last Elegy”

Logorrhea, edited by John Klima. Bantam Books, 2007

“The Voice”

The Flash, edited by Peter Wild, Social Disease, 2007

“Thin”

previously unpublished

“New Practical Physics”

Say…What’s the Combination, 2007

"Mrs. Kafka"

previously unpublished

“Where’s the Rest of Me?”

previously unpublished

“Expositions”

previously unpublished

“The Art of Comedy”

Web Conjunctions, 2006

“Walk in the Light While There is Light”

Failbetter, no. 42, 2012

“A Map of the Everywhere”

Interfictions, edited by Delia Sherman & Theodora Goss, Small Beer Press/ Interstitial Arts Foundation, 2007

“Lacuna”

Where Thy Dark Eye Glances, edited by Steve Berman. Lethe Press, 2013

“The Island Unknown”

Unstuck 2, 2012

Earlier this month, just back from a marvelous and productive

MLA Convention in Austin, Texas, I started to write a post in response to an Inside Higher Ed article on

"Selling the English Major", which discusses ways English departments are dealing with the national decline in enrollments in the major. I had ideas about the importance of senior faculty teaching intro courses (including First-Year Composition), the value of getting out of the department now and then, the pragmatic usefulness of making general education courses in the major more topical and appealing, etc.

After writing thousands of words, I realized none of my ideas, many of which are simply derived from things I've observed schools doing, would make much of a difference. There are deeper, systemic problems, problems of culture and history and administration, problems that simply can't be dealt with at the department level. Certainly, at the department level people can be experts at shooting themselves in the foot, but more commonly what I see are pretty good departments having their resources slashed and transferred to science and business departments, and then those pretty good departments are told to do better with less. (And often they do, which only increases the problem, because if they can do so well with half of what they had before, surely they could stand a few more cuts...) I got through thousands of words about all this and then just dissolved into despair.

Then I read a fascinating post from Roger Whitson:

"English as a Division Rather than a Department". It's not really about the idea of increasing enrollment in English programs, though I think some of the suggestions would help with that, but rather with more fundamental questions of what, exactly, this whole discipline even

is. Those are questions I find more exciting than dispiriting, so here are some thoughts on it all, offered with the proviso that these are quick reactions to Whitson's piece and likely have all sorts of holes in them...

The idea of creating a large division and separating it into departments is not one I support, because I think English departments ought to be more, not less, unified, but it nonetheless provides a template for thinking beyond where we are. (I don't think Whitson or Aaron Kashtan, whose proposal on Facebook Whitson built off of, desires a less unified discipline. But without clear mechanisms for encouraging, requiring, and funding interdisciplinarity, the divisions will divide, not multiply.)

The quoted Facebook post in Whitson's piece basically describes the English department at my university, and each of those pieces (literature, composition, linguistics, ESL, English education, creative writing) has some autonomy, more or less. I'm not actually convinced that that autonomy has been entirely healthy, because it's led to resource wars and has discouraged interdisciplinary work (with each little group stuck talking to each other and not talking enough beyond their own area because there's little administrative support for it and, indeed, quite the opposite: the balkanization has, if anything, increased the bureaucracy and given people more busy-work).

English departments need to seek out opportunities for unity and collaboration. I don't see how dividing things even more than they already are would achieve that, unless frequent collaboration were somehow mandated — for instance, one of the best things about

the program I attended for my master's degree at Dartmouth was that it required us to take some team-taught courses, which allowed fascinating interdisciplinary conversations and work. They could do that because they were Dartmouth and had the money to let lots of faculty collaborate. Few schools are willing to budget that way; indeed, at many places the movement is in the other direction: more students taught by fewer faculty.

Nonetheless, though I am skeptical of separating English departments more than they already are, I like some of Whitson's proposals for ways to reconfigure the idea of what we do and who we are and could be. Even the simple act of using these ideas as jumping-off points for (utopian) conversation is useful.

PlanetarityHere's a key point from Whitson: "I propose asking for more diverse hires by illustrating how important marginalized discourses are to the fields we study, while also investing heavily in opportunities for new interdisciplinary collectives and collaborations." (Utopian, but we're here for utopian discussion, not the practicalities of convincing the Powers That Be of the value of such an iconoclastic, and likely expensive, approach...)

This connects to a lot of conversations I observed or was part of at MLA, particularly among people in the Global Anglophone

Forum (where nobody seems to like the term "global anglophone"). Discussions of the

difficulties for scholars of work outside the US/Britosphere were common. At least on the evidence of job ads, it seems departments are, overall, consolidating away from such areas as postcolonial studies and toward broader, more general, and often more US/UK-centric curriculums. The center is reasserting itself curricularly, defining margins as extensions, roping them into its self-conception and nationalistic self-justification. The effect of austerity on humanities departments has been devasting for diversity of any sort.

I like the idea of "Reading and Writing Planetary Englishes" as a replacement for English Lit, ESL, and parts of Rhet/Comp. Heck, I like it as a replacement for English departments generally. It's not perfect, but nothing is, and "English" is such a boring, imposing term for our discipline...

(Where Comparative Literature — "Reading and Writing Planetary Not-Englishes" — fits within that, I don't know, and it's a question mostly unaddressed in Whitson's post and will remain unaddressed here because questions of literature in translation and literature in languages other than English are too big for what I'm up to at the moment. They are necessary questions, however.)

Spivak's idea of "planetarity" ("rather," as she says, "than continental, global, or worldly" [

Death of a Discipline 72]) is well worth debating, and may be especially appealing in these days of seemingly endless discussion of "the anthropocene" — but what exactly "planetarity" means to Spivak is not easy to pin down. (She can be an infuriatingly vague writer.) Here's one of the most concrete statements on it from

Death of a Discipline:

If we imagine ourselves as planetary subjects rather than global agents, planetary creatures rather than global entities, alterity remains underived from us; it is not our dialectical negation, it contains us as much as it flings us away. And thus to think of it is already to transgress, for, in spite of our forays into what we metaphorize, differently, as outer and inner space, what is above and beyond our own reach is not continuous with us as it is not, indeed, specifically discontinuous. We must persistently educate ourselves into this peculiar mindset. (73)

A more comprehensible statement on planetarity appears in Chapter 21 of

An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization, "World Systems and the Creole":

The experimental musician Laurie Anderson, when asked why she chose to be artist-in-residence at the National Aeronautic and Space Administration, put it this way: "I like the scale of space. I like thinkng about human beings and what worms are. We are really worms and specks. I find a certain comfort in that."

She has put it rather aggressively. That is not my intellectual style, but my point is close to hers. You see how very different it is from a sense of being the custodians of our very own planet, for god or for nature, although I have no objection to such a sense of accountability, where our own home is our other, as in self and world. But that is not the planetarity I was talking about. (451)

On the next page, she makes a useful statement: "We cannot read if we do not make a serious linguistic effort to enter the epistemic structures presupposed by a text." (Technically, yes, we

can read [decode dictionary meanings of words] without such effort, but whatever understanding we come to will be narcissistic, solipsistic.)

And then on p.453: "...I have learned the hard way how dangerous it is to confuse the limits of one's knowledge with the limits of what can be known, a common problem in the academy."

Spivak (here and elsewhere) exhorts us to give up on totalizing ideas. She quotes Édouard Glissant on the infinite knowledge necessary to understand cultural histories and interactions: "No matter," Glissant says, "how many studies and references we accumulate (though it is our profession to carry out such things properly), we will never reach the end of such a volume; knowing this in advance makes it possible for us to dwell there. Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

That could be another motto for our new approach: "Not knowing the totality does not constitute a weakness."

What can be known, then, if not a totality, a thing to be mastered? Our limitations.

What I personally like about transnational, global, planetary, etc. approaches is that their impossibility is obvious and any pretense toward totalized knowledge is going to be laughed at, as it should be.

One point Whitson makes that I disagree with, or at least disagree with the phrasing of, is: "Most undergraduate students in English do not have a good grasp of rhetorical devices (

kairos, chaismus, prosopopoeia) and these would replace 'close reading' (a term that lacks the specificity of the more developed rhetorical tradition) in student learning outcomes and primary classes."

Reading is more than rhetorical analysis. "Close reading" may have a bad reputation, and in some of the ways it's used it deserves that bad reputation, but it remains a useful term for a necessary skill. Especially as we think about ways of communicating what we do to audiences skeptical of the humanities generally, a term like "close reading", which can be understood by people who aren't specialists, seems to me less alienating, and less likely to produce misunderstandings, than "rhetoric". But that may just be my own dislike of the word "rhetoric" and my general feeling that rhetorical analysis is, frankly, dull. (There's a reason I'm not a rhet/comp PhD, despite being at a great school for it.) I wouldn't pull a Whitson and say "We must have no rhetorical analysis and only close reading!" That's silly. There are plenty of reasons to teach rhetorical analysis in introductory and advanced forms. There are also many good reasons to teach and encourage close reading. Making it into an opposition and a zero sum game is counterproductive. After all, rhetorical analysis requires close reading and some close reading requires rhetorical analysis.

In any case, instead of debating rhetorical analysis vs. close reading vs. whatever, what I think we ought to be looking at first is the seemingly simple activity of making meaning from what we read. That unites a lot of approaches with productive questions. (John Ciardi's title

How Does a Poem Mean? has been a guiding, and fruitful, principle of my own reading for a long time.) From there, we can then begin to talk about

interpretive communities, systems of textual analysis, etc: ways of reading, and ways of making sense of texts. Certainly, that includes methods of argument and persuasion. But also much more.

There's much to learn from the field of rhetoric and composition on all that. (In fact, a term from rhet/comp,

discourse communities, can be quite useful here if applied both to the act of reading and the act of writing.) Reading should not — cannot — be the province only of literary scholars. A

recent issue of Pedagogy offers some fascinating articles on teaching reading from a comp/rhet point of view. Further, coming back to Spivak, it seems to me that her work, for all its interdisciplinarity, frequently demonstrates ways that readers have been led astray by not reading closely enough, and her own best work is often in her close readings of texts.

Whitson proceeds to a utopian idea of planetarity (one inherent in Spivak) as a way of broadening ideas of literature beyond the human. This would certainly make room for eco-critics, anthropocene-ists, animal studies folks, etc. This isn't my own interest, and I will admit to quite a lot of skepticism about broadening the idea of "literature" so much that it becomes meaningless, but it's clear that we need such a space within English departments, even for people who think plants write lit. Our departments ought to contain multitudes.

MediaI've taught media courses, and obviously have an interest in, particularly,

cinema. I don't think most such studies belong in English departments, so I am inclined to like the idea of it as a separate department within a general division. While there are plenty of English teachers who teach film and media well, and as an academic field it has some of its origins there, cinema especially seems to me to need people who have significant understanding of visual and dramatic arts. (Just as "new media" [now getting old] folks probably need some understanding of basic computer science.)

Media studies is inherently a site of interdisciplinary work, and that's a good thing. Working side-by-side, people who are trained in visual arts, theatre arts, technologies, etc. can produce new ways of knowing the world.

Something that media studies can do especially well is mix practitioners and analysts. Academia really likes to separate the "practical" people from the "theory" people. This is an unfortunate separation, one that has been detrimental to English departments especially, as literary scholars and writers are too often suspicious of each other. (I'll spare you my rant about how being both a literary scholar and a creative writer is unthinkable in conventional academic English department discourse. Another time.) You'll learn a lot about understanding cinema by taking a film editing class, just as you'll learn a lot about understanding literature by taking a creative writing class. Indeed, I often think the benefit of writing workshops (and their ilk) is not in how they produce better writers, but in how they may enable better readers.

On the other hand, and to argue in some ways against myself, writing and reading teachers ought to be well versed in media, because media mediates our lives and thoughts and reading and writing. To what extent should a department of reading and writing be focused on media, I don't know. Media tends to take over. It's flashy and attracts students. But one thing I fear losing is the

refuge of the English department — the one place where we can escape the flash and fizz of techno-everything, where we can sit and think about a sentence written on an old piece of paper for a while.

EducationI'm less convinced by Whitson's arguments about a division of "Composition Pedagogy and English Education". Why put Composition with English Education and not put some literary study there? Is literary study inherent in "English Education"? Why separate Composition, though? Why not call it "Teaching Reading and Writing"? Perhaps I just misunderstand the goals with this one.

It seems to me that English Education should be some sort of meta-discipline. It doesn't make much sense as a department unto itself in the scheme Whitson sets up, or most schemes, for that matter. Any sort of educational field is very difficult to set up well because it requires students not only to learn the material of their area, but to learn then how to teach that material effectively.

To me, it makes more sense to spread discussion of pedagogy throughout all departments, because one way to learn things is to try to teach them. Ideas about education, and practice at teaching, shouldn't be limited only to people who plan to become teachers, though they may need more intensive training in it.

If we want to be radical about how we restructure the discipline, integrating English Education more fully into the discipline as a whole, rather than separating it out, would be the way to go.

WritingWhitson proposes merging creative and professional writing as one department in the division. This is an interesting idea, but I'm not convinced. Again, my own prejudices are at play: in my heart of hearts, I don't think undergraduates should major in writing. I think there should be writing courses, and there should be lots of writers employed by English departments, but the separation of writing and reading is disastrous at the undergraduate level, leading to too many writers who haven't read nearly enough and don't know how to read anything outside of their narrow, personal comfort zone.

In the late '90s, Tony Kushner scandalized the Association of Theatre in Higher Education's annual conference with

a keynote speech in which he (modestly) proposed that all undergraduate arts majors be abolished. (It was published in the January 1998 issue of

American Theatre magazine.) It's one of my favorite things Kushner has ever written. The whole thing is worth reading, but here's a taste:

And even if your students can tell you what iambic pentameter is and can tell you why anyone who ever sets foot on any stage in the known universe should know the answer to that and should be able to scan a line of pentameter in their sleep, how many think that "materialism" means that you own too many clothes, and "idealism" means that you volunteer to work in a soup kitchen? And why should we care? When I first started teaching at NYU, I also did a class at Columbia College, and none of my students, graduate or undergraduate (and almost all the graduate students were undergraduate arts majors--and for the past 10 years Columbia has had undergraduate arts majors), none of them, at NYU or Columbia, knew what I might mean by the idealism/materialism split in Western thought. I was so alarmed that I called a philosophy teacher friend of mine to ask her if something had happened while I was off in rehearsal, if the idealism/materialism split had become passe. She responded that it had been deconstructed, of course, but it's still useful, especially for any sort of political philosophy. By not having even a nodding acquaintance with the tradition I refer to, I submit that my students are incapable of really understanding anything written for the stage in the West, and for that matter in much of the rest of the world, just as they are incapable of reading Plato, Aristotle, Hegel, Marx, Kristeva, Judith Butler, and a huge amount of literature and poetry. They have, in essence, been excluded from some of the best their civilization has produced, and are terribly susceptible, I would submit, to the worst it has to offer.

What I would hope you might consider doing is tricking your undergraduate arts major students. Let them think they've arrived for vocational training and then pull a switcheroo. Instead of doing improv rehearsals, make them read The Death of Ivan Illych and find some reason why this was necessary in learning improv. They're gullible and adoring; they'll believe you. And then at least you'll know that when you die and go to the judgment seat you can say "But I made 20 kids read Tolstoy!" and this, I believe, will count much to your credit. And if you are anything like me, you'll need all the credits you can cadge together.

Call it the pedagogy of pulling a switcheroo. A good pedagogy, at least sometimes. It doesn't have to be, indeed should not be, limited to Western classics, as Kushner (inadvertently?) implies, and the program he calls for would not be so limited, because the kinds of conversations that he wants students to be able to recognize and join are ones that inevitably became (if they weren't already) transnational, global, even maybe a bit planetary.

So yes, if

I were emperor of universities, I'd abolish undergraduate arts majors, but keep lots of artists as undergraduate teachers. I'd also let the artists teach whatever the heck they wanted. Plenty of writers would be better off teaching innovative classes that aren't the gazillionth writing workshop of their career. Boxing writers into teaching only writing classes is a pernicious practice, one that perpetuates the idea that the creation of literature and the study of literature are separate activities.

But let's come back to Whitson's first proposal: planetarity and the making of textual meaning.

My own inclination is not to separate so much, but to seek out more unities. What unites us? That we study and practice ways of reading and ways of writing. We should encourage more reading in writing classes and more varied types of writing in reading classes. We should toss out our inherited, traditional nationalisms and look at other ways that texts flow around us and around not-us. (Writers do. What good writer was only influenced by texts from one nation?) We should seek out the limits of our knowledge, admit them, challenge them, celebrate them.

Imagination Perhaps what we should think about is imagination. We need more imagination, and we need to educate and promote imagination. So many of the problems of our world stem from failures of imagination — from the

fear of imagination. If you want to be a radical educator, be an educator who inspires students to imagine in better, fuller, deeper ways. The conservative forces of culture and society promote exactly the opposite, because the desire of the status quo is to produce unimaginative (unquestioning, obedient) subjects.

English departments, like arts departments and philosophy departments, are marvelously positioned to encourage imagination. Any student who enters an English class should leave with an expanded imagination. Any student who studies to become an English teacher should be trained in the training of imaginations. We should all be advocates for imagination, activists for its value, its necessity.

One of the best classes I've ever taught was called Writing and the Creative Process. (You can find links to a couple of the syllabi on my

teaching page, though they can't really give a sense of what made the courses work well.) It was a continuously successful course in spite of me. The stakes were low, because it was an introductory course, and yet the learning we all did was sometimes life-changing. This was not my fault, but the fault of having stumbled into a pedagogy that gave itself over entirely to the practice of creativity, which is to say the practice of imagination. Because it was a pre-Creative Writing class, the focus wasn't even on

becoming better writers but rather on

becoming more creative (imaginative) people. That was the key to the success. Becoming a better writer is a nice goal, but becoming a more creative/imaginative person is a vital goal. Were I titling it, I'd have called that course Writing and Creative Process

es, because one of the things I seek to help the students understand is that there is no one process for either writing or for thinking creatively. But no matter. Just by having to think about, talk about, and practice creativity a couple times a week, we made our lives better. I say

we, because I learned as much by teaching that class as the students did; maybe more.

English departments should become departments of writing, reading, and thinking with creative processes.

I began with Spivak, so I'll come back to her, this time from her recent book

Readings:

And today I am insisting that all teachers, including literary criticism teachers, are activists of the imagination. It is not a question of just producing correct descriptions, which should of course be produced, but which can always be disproved; otherwise nobody can write dissertations. There must be, at the same time, the sense of how to train the imagination, so that it can become something other than Narcissus waiting to see his own powerful image in the eyes of the other. (54)

Training — encouraging, energizing — the imagination means a training in aesthetics, in techniques of structure, in ways of valuing form, in how we find and recognize and respond to the beautiful and sublime.

I'm persuaded by Steve Shaviro's arguments in

No Speed Limit about aesthetics as something at least unassimilable by neoliberalism (if not in direct resistance to it): "When I find something to be beautiful, I am 'indifferent' to any uses that thing might have; I am even indifferent to whether the thing in question actually exists or not. This is why aesthetic sensation is the one realm of existence that is not reducible to political economy." (That's just a little sample. See

"Accelerationist Aesthetics" for more elaboration, and the book for the full argument.)

Because the realm of the aesthetic has some ability to sit outside neoliberalism, it is in many ways the most radical realm we can submit ourselves to in the contemporary world, where neoliberalism assimilates so much else.

But training the imagination is not only an aesthetic education, it's also epistemological. Spivak again:

An epistemological performance is how you construct yourself, or anything, as an object of knowledge. I have been consistently asking you to rethink literature as an object of knowledge, as an instrument of imaginative activism. In Capital, Volume 1 (1867), for example, Marx was asking the worker to rethink him/herself, not as a victim of capitalism but as an "agent of production". That is training the imagination in epistemological performance. This is why Gramsci calls Marx's project "epistemological". It is not only epistemological, of course. Epistemological performance is something without which nothing will happen. That does not mean you stop there. Yet, without a training for this kind of shift, nothing survives. (Readings 79-80)

If we're seeking, as Whitson calls us to, to create more diverse (and imaginative) departments of English, then perhaps we can do so by thinking about ways of approaching aesthetics and epistemology. We can be agents of imagination. We don't need nationalisms for that, and we don't need to strengthen divisive organizational structures that have riven many an English department.

We can — we must — imagine better.

A review by another Matt, Matt Zoller Seitz, convinced me to watch

Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine, and I'm glad I did. I wasn't going to, but these sentences got me curious: "It is wrenching but never exploitive. It is impressively skeptical of the same mission that it takes on its shoulders: to make something positive from a senseless crime without diminishing its senselessness."

What kept me from the film had been a fear of it being maudlin or superficial. I know the Shepard case well, I've seen

The Laramie Project a couple of times, I've heard Judy Shepard speak about her son's murder. I didn't think more could, or even should, be made of it. The film proved me wrong.

Matthew Shepard was only a year (and a couple months) older than me. He died a few days before my 23rd birthday. Despite the barrage of national (and international) news coverage, I didn't learn of his murder for a few weeks, because I was in the midst of my first year working full-time at a boarding school, and I barely had time to sleep, never mind keep up with the news. At some point, a friend from college emailed and asked what the climate was like where I was, given how rural and isolated it seemed in my notes to her, and she worried, she said, because of what had happened to the boy in Wyoming. I didn't know what she was talking about at the time, but I soon did.

A rural gay man killed by homophobia. Once I knew about the story, I couldn't get it out of my mind. I followed the trial coverage obsessively. I thought I knew the story pretty well, but one of the excellent things

Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine does is shift the angle. It's no longer the story of someone defined by his murder, though the murder is of course important, but rather the story of Matt Shepard, his friends, and his family. It tries to recover the Matt Shepard who became Matthew Shepard, a symbol for the world. That turns out to be a powerful, gripping, and deeply moving quest.

|

| Michele Josue & Matt Shepard |

It works so well because director Michele Josue is perfectly positioned to do this work — she went to high school with Shepard, but doesn't seem to have stayed closely in touch with him later, and so the film is partly about her own recovery of Matt, her own quest to fill in gaps. What she discovers and chronicles are both the material remnants of his life and, more importantly, the network of people who knew him and remember him. She finds his presence by mapping his absence.

While the film is informative and quite moving with regard to his murder, it's not so much a true crime movie as it is a story of how friendship works and how friendship lasts. It's significant that Josue made the movie fifteen years after Shepard's death, because the time is enough to allow some perspective and to allow us to look back on the legacy, but it's also not so much time that major figures within the story are no longer available. It's also not enough time, if there is such a thing as enough time, to get rid of the pain. A significant section of the film explores Josue's desire to escape grief, and her realization that such escape is not only not possible, but not desireable.

A question that comes up repeatedly, though quietly, throughout the second half of the movie is: Why did this particular crime capture the world's attention? As multiple people point out in the film, gay bashing wasn't (and isn't) especially rare. Dozens of other people were killed for being (or being perceived as) gay in 1998, but it was Shepard's story that moved the world. There's no single answer, and no really definitive answer, though some good partial answers surface, the most convincing being how much Shepard looked and seemed like an ordinary (white) boy from down the street, and how particularly brutal his murder was. (I suspect it resonated, too, because we couldn't help imagining the many hours he spent bleeding alone before he was discovered and helped, though it was too late, ultimately, to save his life. If we imagined that unimaginable time, and if we did so as someone who lived or had once lived in terror of being hurt or killed if our sexuality were known, the resonance was overwhelming and devastating.) He could have been anybody's son, somebody says in the film, which isn't exactly true, of course, but it highlights one of the perceptions that made Shepard's such an irresistible story — his was a familiar sort of face, his family a seemingly familiar sort of family, and his story came from the heart of the American mythos: not just rural but

frontier America, where he was left to die while tied to a fence post. (Later,

Brokeback Mountain would further publicize the idea of all-American gayness through its setting.)

It doesn't feel to me like a long time from Matthew Shepard's death in 1998, and yet it's more than 17 years now. Had he lived, he would have celebrated his thirty-ninth birthday at the beginning of this month. It's hard to imagine Matthew Shepard, the symbol, at thirty-nine, but Josue helps make a thirty-nine-year-old Matt imaginable, and thus makes his death all the more heartbreaking.

That heartbreaking quality surprised me in the film, because after the initial shock of the story, for those of us who weren't friends with Matt Shepard, his death actually came to stand for a lot of good progress that was made afterward. I have very mixed feelings about the assimilationist success of

Gay, Inc., but I really never expected to see federal gay marriage in my lifetime, to see gay kisses become relatively normalized on tv and in mainstream movies, to see anything remotely like

Sense8 from anyplace other than the very indie and very queer world, etc. Watching

Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine, I remembered what it used to feel like to live in terror of anybody finding out, or even just suspecting, that you're not entirely heterosexual. It's not that the terror's all gone, or that we're all safe and happy and prosperous etc., or that there aren't still bashings and murders (in 2014

the FBI counted "1,248 victims [of hate crimes] targeted due to sexual-orientation bias" and

suicide remains an ever-present problem). But in many places of the U.S. now, it is easier to live openly as a gay, lesbian, or bisexual person than it was fifteen or twenty years ago. The culture (or, at least, part of the dominant culture) has shifted, and Matthew Shepard's murder — and the conversations and work that murder inspired — contributed to the shift.

Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine reminds us of this, and it does a lot more besides. It pays close attention to how people continued their lives after his death. It shows why his death remains meaningful, and why his life deserves to be remembered. It suggests much about forgiveness, about grieving, about news media, and about living with questions that can't be answered. It is, finally, a beautiful tribute to a friend, and to a grief that cannot, and should not, be lost.

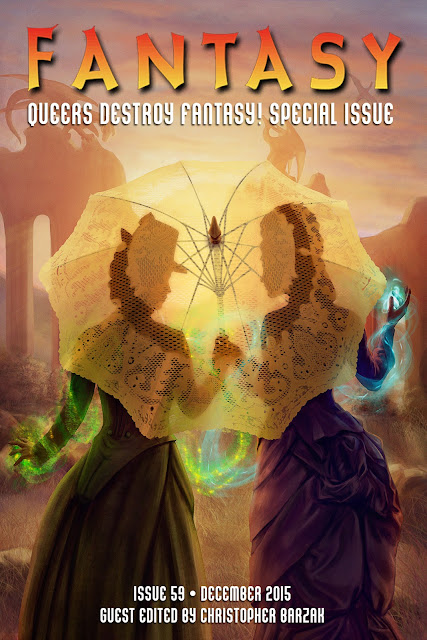

I was honored to be the nonfiction editor for a special issue of

Fantasy magazine, part of the ever-growing

Destroy series from

Lightspeed, Nightmare, and

Fantasy — this time,

QUEERS DESTROY FANTASY!The editor-in-fabulousness/fiction editor was Christopher Barzak, the reprints editor was Liz Gorinsky, and the art editor was Henry Lien. Throughout this month, some pieces will be put online. So far,

Austin Bunn's magnificent story

"Ledge" is now available, as are our various

editorial statements. More will be released later, but most of the pieces I commissioned are only available by purchasing the

ebook [also available via

Weightless] or

paperback. There are magnificent pieces by Mary Anne Mohanraj, merritt kopas, Keguro Macharia, Ekaterina Sedia, and Ellen Kushner, and only merritt's "Sleepover Manifesto" will be online.

I owe huge thanks to all the contributors I worked with, to the other editors, to managing editor Wendy Wagner who did lots of unsung work behind the scenes, and to John Joseph Adams, who kindly asked me to join the team.

It is far too early to tear down the barricades. Dancing shoes will not do. We still need our heavy boots and mine detectors.

—Jane Marcus, "Storming the Toolshed"

1. Seeking Refuge in Feminist Revolutions in ModernismLast week, I spent two days at the

Modernist Studies Association conference in Boston. I hadn't really been sure that I was going to go. I hemmed and hawed. I'd missed the call for papers, so hadn't even had a chance to possibly get on a panel or into a seminar. Conferences bring out about 742 different social anxieties that make their home in my backbrain. I would only know one or maybe two people there. Should I really spend the money on conference fees for a conference I was highly ambivalent about? I hemmed. I hawed.

In the end, though, I went, mostly because my advisor would be part of a seminar session honoring the late

Jane Marcus, who had been her advisor. (I think of Marcus now as my grandadvisor, for multiple reasons, as will become clear soon.) The session was titled "Thinking Back Through Our Mothers: Feminist Revolutions in Modernism", the title being an homage to Marcus's essay "Thinking Back Through Our Mothers" from the 1981 anthology

New Feminist Essays on Virginia Woolf, itself an homage to the phrase in Woolf's

A Room of One's Own. Various former students and colleagues of Marcus would circulate papers among themselves, then discuss them together at the seminar. Because of the mechanics of seminars, participants need to sign up fairly early, and I'd only registered for the conference itself a few days before it began, so there wasn't even any guarantee I'd been able to observe; outside participation is at the discretion of the seminar leader. Thankfully, the seminar leader allowed three of us to join as observers. (I'm trying not to use any names here, simply because of the nature of a seminar. I haven't asked anybody if I can talk about them, and seminars are not public, though the participants are listed in the conference program.)

Marcus was a socialist feminist who was very concerned with bringing people to the table, whether metaphorical or literal, and so of course nobody in the seminar would put up with the auditors being out on the margins, and they insisted that we sit at the table and introduce ourselves. Without knowing it, I sat next to a senior scholar in the field whose work has been central to my own. I'd never seen a picture of her, and to my eyes she looked young enough to be a grad student (the older I get, the younger everybody else gets!). When she introduced herself, I became little more than a fanboy for a moment, and it took all the self-control I could muster not to blurt out some ridiculousness like, "I just love you!" Thankfully, the seminar got started and then there was too much to think about for my inner fanboy to unleash himself. (I did tell her afterwards how useful her work had been to me, because that just seemed polite. Even senior scholars spent a lot of hours working in solitude and obscurity, wondering if their often esoteric efforts will ever be of any use to anybody. I wanted her to knows that hers had.) It soon became the single best event I've ever attended at an academic conference.

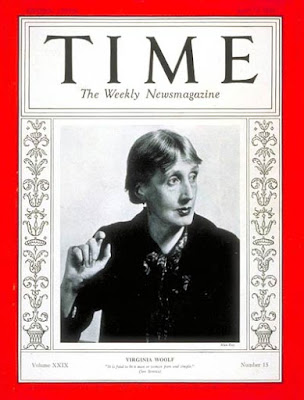

|

| Jane Marcus |

To explain why, and to get to the bigger questions I want to address here, I have to take a bit of a tangent to talk briefly about a couple of other events.

The day before the Marcus seminar, I'd attended a terrible panel. The papers that were about things I knew about seemed shallow to me, and the papers not about things I knew about seemed like pointless wankery. I seriously thought about just going home. "These are not my people," I thought. "I do not want to be in their academic world."

I also attended a "keynote roundtable" session where three scholars — Heather K. Love, Janet Lyon, and Tavia Nyong’o — discussed the theme of the conference: modernism and revolution. Sort of. It was an odd event, where Love and Nyong'o were in conversation with each other and Janet Lyon was a bit marginalized, simply because her concerns were somewhat different from Love and Nyong'o's and she hadn't been part of what is apparently a longstanding discussion between them. I mention this not as criticism, really, because though the side-lining of Lyon felt weird and sometimes awkward, the discussion was nonetheless interesting and vexing in a productive way. (I know Love and Nyong'o's work, and appreciate it a lot.) I especially appreciated their ideas about academia as, ideally, a refuge for some types of people who lack a space in other institutions and have been marginalized by ruling powers, even if there are no real solutions, given how deeply infused with ideas of finance and "usefulness" the contemporary university is, how exploitative are the practices of even small schools. (Nyong'o works at NYU, an institution that has become

the mascot for neoliberalism. His recent blog essay

"The Student Demand" is important reading, and was referenced a number of times during the roundtable.) As schools make more and more destructive decisions at the level of administration and without the faculty having much obvious ability to challenge them, the position of the tenure-tracked, salaried faculty member of conscience is difficult, for all sorts of reasons I won't go into here. As Nyong'o and Love pointed out, the moral position must often be that of a criminal in your own institution.

All of this was on my mind the next day as I listened to discussions of Jane Marcus. After the seminar, some of us went out to lunch together and the discussion continued. What I kept thinking about was the idea of refuge, and the way that certain traditions of teaching and writing have opened up spaces of refuge within spaces of hostility. Marcus stands as an exemplar here, both in her writing and her pedagogy. The question everyone kept coming back to was: How do we continue that work?

In her 1982 essay "Storming the Toolshed", Marcus reflected on the position of various feminist critics ("lupines" — she appropriated Quentin Bell's dismissive term for feminist Woolfians, reminding us that it is also a name for a

flower):