I was asked the plotter versus pantser question while I was on an author panel at the Young Adult Keller Book Festival this past weekend (YAKFEST) (which was wonderful!), and as usual I felt a little deer-in-the-lightsish. And my answer, as usual, is that I'm a plantser.

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: plotting, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 84

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Martina Boone, Character Development, Plotting, Craft of Writing, Synopsis, Add a tag

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Plotting, WOW Wednesday, Add a tag

Asking Better Questions by Eric Lindstrom

The fourth doctor of the TV series Doctor Who was my childhood hero. (He still is, but that’s a different story.) In an episode I watched as a teen, he said, “Answers are easy – it’s asking the right questions which is hard.” It was my first exposure to this idea, and it stuck with me.Over time this perspective became a very useful tool. When I get stuck and can’t find an answer, stepping back and examining my questions often leads to a solution. This process proves itself useful in many different ways, but here I’ll focus on a key example.

Starting out as a writer, I sometimes found myself blocked, wondering, “What should happen next?” I came to understand (over years, not one Saturday afternoon) how that was the wrong question. Tornados happen. Wildebeest migrations happen. But the vast majority of events in a story don’t just happen. Characters make them happen. “What happens next?” is appropriate for the reader to ask, not the writer.

Read more »

Blog: The Bookshelf Muse (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Uncategorized, Motivation, Writing Craft, Fear, Plotting, Villains, Emotion, Show Don't Tell, Empathy, Writing Lessons, Emotion Thesaurus Guide, Positive & Negative Thesaurus Guides, One Stop For Writers, Characters, Description, Character Traits, Character Arc, Character Flaws, Character Wound, Basic Human Needs, Add a tag

It’s NaNoWriMo Season, and that means a ton of writers are planning their novels. Or, at the very least (in the case of you pantsers) thinking about their novel.

Whether you plot or pants, if you don’t want to end up in No Man’s Land halfway to 50K, it is often helpful to have a solid foundation of ideas about your book. So, let’s look at the biggie of a novel: Character Arc. If you plot, make some notes, copious notes! If you pants, spend some time mulling these over in the shower leading up to November 1st. Your characters will thank you for it!

Are you excited? I hope so. You’re about to create a new reality!

Can you imagine it, that fresh page that’s full of potential? Your main character is going to…um, do things…in your novel. A great many things! Exciting things. Dangerous things. There might even be a giant penguin with lasers shooting out of its eyes, who knows?

But here’s a fact, my writing friend…if you don’t know WHY your protagonist is doing what he’s doing, readers may not care enough to read beyond a chapter or two.

The M word…Motivation

It doesn’t matter what cool and trippy things a protagonist does in a story. If readers don’t understand the WHY behind a character’s actions, they won’t connect to him. We’re talking about Motivation, something that wields a lot of power in any story. It is the thread that weaves through a protagonist’s every thought, decision, choice and action. It propels him forward in every scene.

Because of this, the question, What does my character want? should always be in the front of your mind as you write. More importantly, as the author, you should always know the answer.

Outer Motivation – THE BIG GOAL (What does your character want?)

Your character must have a goal of some kind, something they are aiming to achieve. It might be to win a prestigious award, to save one’s daughter from kidnappers, or to leave an abusive husband and start a new life. Whatever goal you choose, it should be WORTHY. The reader should understand why this goal is important to the hero or heroine, and believe they deserve to achieve it.

Your character must have a goal of some kind, something they are aiming to achieve. It might be to win a prestigious award, to save one’s daughter from kidnappers, or to leave an abusive husband and start a new life. Whatever goal you choose, it should be WORTHY. The reader should understand why this goal is important to the hero or heroine, and believe they deserve to achieve it.

Inner Motivation – UNFULFILLED NEEDS (Why does the protagonist want to achieve this particular goal?)

Fiction should be a mirror of real life, and in the real world, HUMAN NEEDS DRIVE BEHAVIOR. Yes, for you psychology majors, I am talking about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs. Physical needs, safety and security, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization are all part of what it is to be human.

Fiction should be a mirror of real life, and in the real world, HUMAN NEEDS DRIVE BEHAVIOR. Yes, for you psychology majors, I am talking about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs. Physical needs, safety and security, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization are all part of what it is to be human.

If you take one of these needs away, once the lack is felt strongly enough, a person will be DRIVEN to gain it back. The need becomes so acute it can no longer be ignored–it is a hole that must be filled.

If someone was threatening your family (safety and security) what might you do to keep loved ones safe? If each day you went to a workplace where you were treated poorly by your boss (esteem), how long until you decide to look for a new job? These needs are real for us, and so they should be real for our characters. Ask yourself what is missing from your character’s life. Why do they feel incomplete? The story becomes their journey to fill this lack.

Outer Conflict – THE WHO or WHAT (that stands in the way of your hero achieving his goal)

Outer Conflict – THE WHO or WHAT (that stands in the way of your hero achieving his goal)

If your story has an antagonist or villain, you want to spend some solid time thinking about who they are, why they’re standing in the hero’s way, and what motivates them to do what they do.

The reason is simple…the stronger your antagonist is, the harder your hero must work to defeat him. This also means the desire of achieving the goal must outweigh any hardship you throw at your hero, otherwise he’ll give up. Quit. And if he does, you’ll have a Tragedy on your hands, not the most popular ending.

Our job as authors is to challenge our heroes, and create stakes high enough that quitting isn’t an option. Often this means personalizing the stakes, because few people willingly put their head in an oven. So make failure not an option. Give failure a steep price.

The problem is that with most stories, to fight and win, your character must change. And change is hard. Change is something most people avoid, and why? Because it means taking an honest look within and seeing one’s own flaws. It means feeling vulnerable…something most of us seek to avoid. This leads us to one of the biggest cornerstones of Character Arc.

Inner Conflict – The STRUGGLE OVER CHANGE (an internal battle between fear and desire, of staying chained to the past or to seek the future)

To achieve a big goal, it makes sense that a person has to apply themselves and attack it from a place of strength, right? Getting to that high position is never easy, not in real life, or in the fictional world. In a novel, the protagonist has to see himself objectively, and then be willing to do a bit of housecleaning.

What do I mean by that?

Characters, like people, bury pain. Emotional wounds, fears, and vulnerability are all shoved down deep, and emotional armor donned. No one wants to feel weak, and when someone takes an emotional hit after a negative experience, this is exactly what happens. They feel WEAK. Vulnerable.

The Birth of Flaws

What is emotional armor? Character Flaws. Behaviors, attitudes and beliefs that a character adopts as a result of a wounding event. Why does this happen? Because flaws minimize expectations and keep people (and therefore their ability to cause further hurt) at a distance. But in doing so, flaws create dysfunction, damage the protagonist’s relationships and prevent his personal growth. And due to their negative nature, flaws also tend to get in the way, tripping the character up and prevent him from success.

Facing Down Fear

Fear, a deeply rooted one, is at the heart of any flaw. The character believes that the same painful experience (a wound or wounds) will happen again if unchecked. This belief is a deeply embedded fear that blinds them to all else, including what is holding them back from achievement and happiness.

To move forward, the protagonist must see his flaws for what they are: negative traits that harm, not help. He must choose to shed his flaws and face his fears. By doing this, he gains perspective, and views the past in a new light. Wounds no longer hold power. False beliefs are seen for the untruths they are. The character achieves insight, internal growth, and fortified by this new set of beliefs, is able to see what must be done to move forward. They finally are free from their fear, and are ready to make the changes necessary to achieve their goal.

Why Does Character Arc Hold Such Power Over Readers?

This evolution from “something missing” to “feeling complete” is known as achieving personal growth in real life, which is why readers find Character Arc so compelling to read about. As people, we are all on a path to becoming someone better, someone more whole and complete, but it is a journey of a million steps. Watching a character achieve the very thing we all hope to is very rewarding, don’t you think?

Need a bit more help with some of the pieces of Character Arc? Try these:

Why Is Your Character’s Emotional Wound So Important?

Emotional Wounds: A List Of Common Themes

The Connection Between Wounds and Basic Human Needs

Flaws, Emotional Trauma and The Character’s Wound

Make Your Hero Complex By Choosing The Right Flaws

Explaining Fears, Wounds, False Beliefs and Basic Needs

And did you know…

And did you know…

The bestselling books, The Emotion Thesaurus, The Negative Trait Thesaurus and The Positive Trait Thesaurus are all part of One Stop For Writers, along with many other upgraded and enhanced description collections?

You can also access many workshops and templates to help with Character Arc, or take our Character Wound & Internal Growth Generators for a spin.

Are you NaNoing this year? How is your Character Arc coming along? Let me know in the comments!

The post Planning a Novel: Character Arc In A Nutshell appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS™.

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Plotting, Craft of Writing, Inspiration for Writers, Martina Boone, Add a tag

Writing a novel isn't magic. I'd like to say that anyone can write a book--and truly, almost anyone can. The trick is sticking with it, making it good, and getting it published.

Ah, there's the rub. Frequently when someone asks me "How do you write a book?" what they're really asking is "How do I get a book published?"

There are a thousand ways to answer that, but the most honest on is once a book is that no one can guarantee publication. Once a book is at a certain level of competency, no matter how good it is, or how many books you've written or previously published, sometimes what separates a book that gets a book deal from one that doesn't comes down to luck.

You can't control luck, but there are a number of things that will make it easier if you want to write a book that has a chance of traditional publication, or of successful indie publication.

Read more »

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Story Structure, Plotting, Best of AYAP, Add a tag

When struck with a shiny new idea, all you want to do is get stuck into creating it into the masterpiece you know it can be. For some of us, that means sitting down and plotting up a storm. For others, it means jumping straight into that first draft. And for some of us, it simply means grabbing a pen and paper and dreaming the day away.

Whatever your preferred method, structure and plot is an important part of making a novel come to life. So whether you're a pantser, or a plotter, or somewhere in between, you'll no doubt find the posts below invaluable. Read on for a collection of posts aimed at shaping your story into the best story it can possibly be.

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Endings, Plotting, Craft of Writing, Amy Fellner Dominy, Add a tag

We're very pleased to welcome author Amy Fellner Dominy to the blog today. If there's one thing more important than how you start your story, it's how you end it. Amy offers some excellent advice for crafting an ending that your reader will be sure to love...and remember.

And be sure to check out Amy's new release, A Matter of Heart!

Crafting a Satisfying Ending to Your Story, A Craft of Writing Post by Amy Fellner Dominy

ENDINGS

As summer winds down it seems like a good time to talk about endings.Great endings make you sigh, tear-up or smile. They make you sad for the book to be over, and they make you want to flip the pages and go back to the beginning and start again. Great endings are, simply put, satisfying.

If only they were simple to write.

So, here are a few suggestions to help you craft a satisfying ending to your story.

Read more »

Blog: The Open Book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plotlines, New Voices Award, Writer Resources, As Fast As Words Could Fly, Pamela Tuck, Lee & Low Likes, New Voices/New Visions Award, jennifer torres, Interviews with Authors and Illustrators, finding the music, plotting a story, Awards, plot, plotting, Add a tag

This year marks our sixteenth annual New Voices Award, Lee & Low’s writing contest for unpublished writers of color.

This year marks our sixteenth annual New Voices Award, Lee & Low’s writing contest for unpublished writers of color.

In this blog series, past New Voices winners gather to give advice for new writers. This month, we’re talking about tools authors use to plot their stories.

Pamela Tuck, author of As Fast As Words Could Fly, New Voices Winner 2007

One tip I learned from a fellow author was that a good story comes “full circle”. Your beginning should give a hint to the ending, your middle should contain page-turning connecting pieces, and your ending should point you back to the beginning.

The advantage I had in writing As Fast As Words Could Fly, is that it was from my dad’s life experiences, and the events were already there. One tool that helped me with the plot was LISTENING to the emotions as my dad retold his story. I listened to his fears, his sadness, his excitement, and his determination. By doing this, I was able to “hear” the conflict, the climax, and the resolution.

One major emotion that resonates from my main character, Mason, is confidence. I drew this emotion from a statement my dad made: “I kept telling myself, I can do this.” The challenging part was trying to choose which event to develop into a plot. My grandfather was a Civil Rights activist, so I knew my dad wrote letters for my grandfather, participated in a few sit-ins, desegregated the formerly all-white high school, learned to type, and entered the county typing tournament. Once I decided to use his typing as my focal point, the next step was to create a beginning that would lead up to his typing. This is when I decided to open the story with the idea of my dad composing hand-written letters for his father’s Civil Rights group. I threw in a little creative dialogue to explain the need for a sit-in, and then I decided to introduce the focal point of typing by having the group give him a typewriter to make the letter writing a little easier. To build my character’s determination about learning to type, I used a somewhat irrelevant event my dad shared: priming tobacco during the summer. However, I used this event to support my plot with the statement: “Although he was weary from his day’s work, he didn’t let that stop him from practicing his typing.” His summer of priming tobacco also gave me an opportunity to introduce two minor characters who would later add to the tension he faced when integrating the formerly all-white school.

The second step was to concentrate on a middle that would show some conflict with typing. This is when I used my dad’s experiences of being ignored by the typing teacher, landing a typing job in the school’s library and later being fired without warning, and reluctantly being selected to represent his school in the typing tournament.

Lastly, I created an ending to show the results of all the hard work he had dedicated to his typing, which includes a statement that points back to the beginning (full circle).

Although the majority of the events in As Fast As Words Could Fly are true, I had to carefully select and tweak various events to work well in each section, making sure that each event supported my plot.

Jennifer Torres, author of Finding the Music, New Voices Winner 2011

I’m a huge fan of outlines and have a hard time starting even seemingly simple stories without one. An outline gives me and my characters a nice road map, but that’s not always enough. Once I had an outline for Finding the Music, it was really helpful to visualize the plot in terms of successive scenes rather than bullet points. I even sketched out an actual map to help me think about my main character Reyna’s decisions, development and movement in space and time.

Still, early drafts of the story meandered. There were too many characters and details that didn’t move the plot forward. When stories begin to drift like that, I go back to my journalism experience: Finding the Music needed a nut graph, a newspaper term for a paragraph that explains “in a nutshell” what the story is really about, why it matters. Finding the Music is about a lot of things, but for me, what it’s *really* about is community—the community Reyna’s abuelo helped build through this music and the community Reyna is part of (even though it’s sometimes noisier than she’d like). I think Reyna’s mamá captures that idea of community when she says, “These are the sounds of happy lives. The voices of our neighbors are like music.”

Once I found the heart of the story, it was a lot easier to sharpen up scenes and pull the plot back into focus.

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Young Adult Fiction, Plotting, Craft of Writing, Tension, Martina Boone, YA Fiction Giveaways, Add a tag

I'm about to spill one of my worst kept writing secrets, by which I mean that I'm going to talk about why I include a lot of the kinds of scenes that legendary agent and author Donald Maass, whose many books about writing I usually agree with in their entirety, says to leave out of a novel. What kind of scenes are those? The ones that take place in kitchens, living rooms, and cars driving back and forth. Let's call them the everyday scenes.

I'm about to spill one of my worst kept writing secrets, by which I mean that I'm going to talk about why I include a lot of the kinds of scenes that legendary agent and author Donald Maass, whose many books about writing I usually agree with in their entirety, says to leave out of a novel. What kind of scenes are those? The ones that take place in kitchens, living rooms, and cars driving back and forth. Let's call them the everyday scenes.

Now it's true that these scenes are the ones that usually are left out of successful novels--especially young adult novels. Why? Because they tend to be low-tension scenes. Scenes where people are sitting around talking and not much is happening.

But low action doesn't have to mean low tension. Novels aren't necessarily about action; they're about conflict. And conflict can occur anywhere. That's what a lot of writers overlook, and it can result in low-tension (aka boring) action scenes as well as scenes that end up being just two characters talking.

There are many valid reasons to have those everyday scenes, though. Which means it's a good thing there are easy ways to beef them up so they engage instead of disengage your reader.

Read more »

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Martina Boone, Inspired Openings, YA Fiction Giveaways, Young Adult Fiction, Character Development, Plotting, Craft of Writing, GMC, Add a tag

I was reading an interview with NYT Bestselling author Tess Gerritsen over on Novel Rocket, yesterday, and she mentioned that her favorite piece of writing advice is to focus on the character's predicament. I love, love, love that, because it actually addresses four different aspects of your WIP.

Here's how.

- Start by putting yourself in your character's head. What's her problem? What no-win predicament does she find herself in? Journal this, just as a rough paragraph or two or three, writing as if she is screaming at someone for putting her in that situation. Let it all loose. Imagine the confrontation, all the emotion, the frustration, the desire to move forward and fix something.

- Examine that thing that she has to fix and establish the consequences if she fails. Brainstorm why she wants to fix it and jot it down your on one page in a notebook, note software program, or on a Scrivener entry. Why does she need to fix the problem? Why does she have no choice to act to change that situation?

- What is your character willing or forced to give up to fix her predicament? Add a second page to your notes. Write down what is most important to your character. Explore what defines her view of herself, and how this predicament effects that. What wound from her past or weakness of character is going to make it harder for her to repair the problem? What unexpected strengths can she find along the way that will help her?

- Now build your plot like dominos. Once you have a pretty good grasp on the predicament itself, it's relatively easy to make a timeline of how the problem, the person who created that problem (or personifies it) and your character intersect. You can build your plot as if it's inevitable: this happened, your character reacted, because your character reacted, this other thing happened, and so on. One thing leads directly to another.

- Next, taking into consideration who your character is, find the place in the timeline, or right before what you've jotted down, where the problem first rears its head. This could be something that your character did that set the problem in motion, or something coming in from outside to shake things up, but there has to be a change. This is where you're going to begin your story, on the day that is different, with the first domino. Write down what that incident is.

- Finally, put everything together to set up the story. Your opening has to show the inciting incident, suggest the story problem, and jump start the action, but you also want to foreshadow your character's strength and the weakness that is going to hold her back. You want to give us a hint of the personal lesson she will have to learn in order to get out of the predicament she's facing.

This Week's Giveaway

An Ember in the Ashes

An Ember in the AshesHardcover

Razorbill

Released 4/28/2015

I WILL TELL YOU THE SAME THING I TELL EVERY SLAVE.

THE RESISTANCE HAS TRIED TO PENETRATE THIS SCHOOL COUNTLESS TIMES. I HAVE DISCOVERED IT EVERY TIME.

IF YOU ARE WORKING WITH THE RESISTANCE, IF YOU CONTACT THEM, IF YOU THINK OF CONTACTING THEM, I WILL KNOW

AND I WILL DESTROY YOU.

LAIA is a Scholar living under the iron-fisted rule of the Martial Empire. When her brother is arrested for treason, Laia goes undercover as a slave at the empire’s greatest military academy in exchange for assistance from rebel Scholars who claim that they will help to save her brother from execution.

ELIAS is the academy’s finest soldier— and secretly, its most unwilling. Elias is considering deserting the military, but before he can, he’s ordered to participate in a ruthless contest to choose the next Martial emperor.

When Laia and Elias’s paths cross at the academy, they find that their destinies are more intertwined than either could have imagined and that their choices will change the future of the empire itself.

Purchase An Ember in the Ashes at Amazon

Purchase An Ember in the Ashes at IndieBound

View An Ember in the Ashes on Goodreads

More Giveaways

What About You?

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: creative writing, writing exercise, outlining, First Drafts, plotting, first draft, first lines, opening, novel openings, Add a tag

The Aliens Inc, Chapter Book Series

Try Book 1 for Free

I’ve been fiddling with the opening of the second book of a trilogy, Blue Planets, for several weeks, trying to plot, trying to think of new and exciting ways to tell the story. I KNOW the story. It’s bringing it down to specifics that’s hard.

Part of my problem is that Book 1 in this trilogy opens with a scene that echoes the movie “Jaws.” That book and movie has a powerful, action packed opening image and scene that sets up the stakes clearly. My Book 1 opening echoes the action, and twists the meaning into a new, surprising direction. I like the opening I create there.

But it also set up a problem: How can I echo the “Jaws” opening for Book 2?

I’ve struggled for a couple weeks with this question and finally found the answer.

Don’t. Find another image that works.

Using a Mentor Text or Story

Perhaps, though, the process I used in the opening for Book 1 can be repeated for Book 2. I used “Jaws” as a mentor text, echoing its action and setting the stakes very high. What if I found a different mentor text/movie for the next book?

At Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat site, they’ve done a series of analyses of movie plots that are called Beat Sheets under his system. I decided to go through them and write a short summary of how I could or couldn’t echo the different movies for this opening. I knew that I had to approach it as a writing exercise and just go overboard and let the ideas flow.

In an hour, I wrote the summaries for the following twenty possible opening scenes. After, I went back and wrote a sentence of how the closing scene might echo back to the opening scene. That closing scene ideas — only written after all the opening scene summaries were completed — helped me evaluate how well this opening fit my story. Note also that I drew a blank on about three of the movie openings and couldn’t figure out how it would fit my story.

The Grunt Work: Writing 20 Possible Summaries of Opening Scene

Note: You won’t understand what some of this means, since I’m not explaining all the background, setting, characters, etc. That’s OK. The point is to see how I echoed the mentor text/story in some way. The link for each movie title goes to the Save the Cat plot analysis for that movie, where you can read the opening image synopsis and compare it to mine. You may think some of my opening as strangely at odds with the mentor text. That’s fine. I consider the mentor text/story as merely a starting point and go where the story takes me.

- A la Ultron.

The opening image is of a huge conch shell that is blown and echoes throughout the ocean. Jake is swimming and hears it—has to stop up his ears it’s so loud. But no human hears it—at a weird frequency. It’s an emergency call to the Mer, but Jake doesn’t know that yet. The umjaadi plague is spreading and they still don’t know what it is.

Final Echo: A hospital ward full of sick patients and the doctor telling someone that unless someone finds a cure, they’ll all die. The Mer will be gone. - A la The Conversation .

The opening image is Edinburgh, Scotland the castle with a full moon overhead. Home of Harry Potter, the setting is almost mythical. But the reality of walking the seven hills, and climbing up the highest pulls Jake back to Earth (so to speak). From the top, he sees the Frith of Forth and the bridge—with the aquarium under it, where they’ll go tomorrow.

Final echo: back on the hill, Jake now understands what is beneath the waters he sees. - A la Whiplash.

Jake is swimming laps in a pool—with no one around—when Cy Blevins walks in. You’re not related to the Commander, you’re the Ambassador’s son—we know all about you. OK. So, what? You can’t live here.

Jake swims, but wants to jump out and beat up Cy.

Final echo: No. Doesn’t work. - A la Birdman.

Jake is swimming and keeps asking himself, “How did we wind up here? Am I Earthling or Risonian?” He turns sharks into tour guides, he is thrilled with electric shock from eels, he talks to octopuses.

Final echo: I am Earthling.

Jake is a toddler swimming on Rison and when a camouflaged creature (octopus-like) unfurls, he is startled and starts to cry. Turns to Swann for comfort, but Swann turns him around and says, SEE. Watch. Learn to see.

Final echo: Swimming and points out a camouflaged creature to Swann.

B/w documentary about octopuses, compared with what we know today. They were once feared as monsters, but we now know they are very intelligent (playing with toys to get crabs). We see what we expect to see, and that changes slowly. (Or: what’s alien comes from what’s in OUR heads, not what we see in front of us.)

Final echo: B/W Risonain documentary on first contact Earth—from the Risonian POV. We now know Earthlings are much more complicated and intelligent than we thought at first.

Go for a memory and emotion. Jake relives a moment with Em where they kiss—or almost kiss. But then shakes himself. No. She didn’t want to be friends.

Final echo: A final kiss.

The camera moves along an underwater ship and reveals it to be a U-Boat. Follow with the scene of the DCS dive.

Final echo: Maybe Mom is sick from something on Earth?

(Scene with dramatic first kill – will he shoot a kid?)

Scene with dramatic first ______?

Clearly, this one didn’t work.

From a boat, Dr. Max Bari lowers a figure on a stretcher into the ocean, then dives in after her—without scuba gear. He tugs the stretcher deeper and deeper until there are lights in the distance. . .

Final echo: Jake lifts off in a rocket ship and watches Earth get smaller and smaller in the distance, and turns his face toward Rison and hopes. . .

Setting: Sanfransokyo

My Setting: Aberforth Hills

Final echo: Earth leaders touring Aberforth Hills

In a classroom, they are going around telling what their fathers do. A young Jake says his father is a test tube. No, it’s the Leader of our People. No, it’s really a test tube.

Final echo: Jake with Dad.

(Ambush of triumphant soldier by vanquished.) No ideas. Didn’t work for me.

(Sharp contrast of emotions: head on shoulder of husband contrasted with his thoughts of killing her. Result: Worry for her safety)

Contrasting emotions? Invade Earth and just take it! Take the long, slow route to a long-term healthy relationship.

Mom is giving a speech to the world leaders about Rison’s needs. Jake is drawing pictures of skulls and wishing he could blast all of Earth so Risonians could take over. How can they ever live together on the same planet and not kill each other?

Final echo: Fight that ends in a truce.

Sitting alone, Jake is listening to a cd mix that Em gave him and wishing they hadn’t quarreled. He gets a call from Marisa, who says she wants to meet with him. I hear you’re going to Edinburgh. Mom and Dad aren’t saying much—but I think Em has been kidnapped and they know who did it, but they won’t go after her. I think she’s somewhere near Edinburgh.

Final echo: Jake gives Em a cd of Risonian operas and says, I’ll be back with the cure.

Jake is spinning a globe of the world and narrating for his class (OR Swann) back home-videoconference call. He tells of how Earthlings/US once put it’s citizens in jail because they “might” have been traitors. How they questioned the loyalty of citizen merely because of their heritage. How unfair it is and how he’s worried that the Risonians will be even more feared and how suspicion will abound.

Final echo: Suspicious news reports: There are fears that Jake Quad-di is returning home with intelligence that will allow the Risonians to attack. His mother, Ambassador Dayexi Quad-di assures us that he only returns to bring back a cure for the Phoke. But why would he risk his life for them?

The camera pans across oceans, racing across the seas, until it zooms in on a conference room where Mom is talking to world leaders, a clear image of politics/diplomacy.

Final echo: Not emotional enough to pursue.

Start with pan down from The End—the last movie—and sing about how the studio ordered a sequel.

Final echo: No. Don’t like this metadata stuff.

Jake is writing a letter to the editor, or editorial or something—and we pull back to see that he’s writing it for Mom. He’s her assistant now, and she trusts his knowledge of English and culture. (Not emotional enough. HER is a love story, so the emotions there are about truly falling in love. It’s not going to work in this story.)

The scene opens on a rowdy swimming pool with kids taking bets. Jake lines up with another guy and when the whistle blows, the other boy dives in and races away. When that guy touches the opposite wall, Jake dives in, velcroes his legs and swims. He almost beats the other guy back, but is won out by a touch.

I win! Says the other swimmer.

Jake shakes his head. He swam almost twice as fast—and the Earthling says he won? That’s crazy.

We’re never letting you compete in the Olympics! Says one kid.

Final echo: Argument: You think I can do miracles. Sure, I can outswim any human boy, but on Rison, I’m nothing. I’m just a normal kid. How can I find the cure to the umjaadi in time? I can’t. But I have to try.

Notice that I didn’t hold myself to an impossible standard. If the movie’s opening didn’t spark something almost immediately, I moved on. Further, I didn’t stop at just one try. I persevered, knowing that I needed to fully explore my options.

Evaluate the Possible Openings

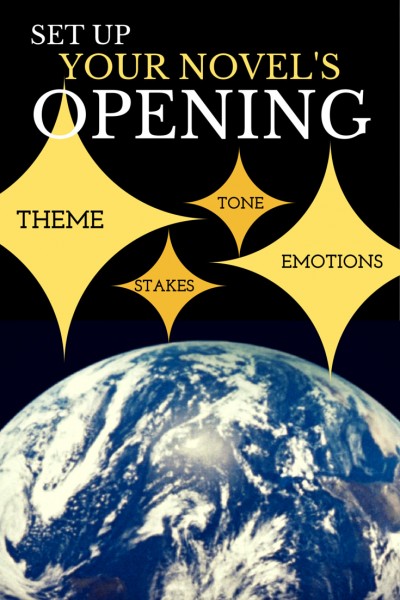

After writing all of these, I had to evaluate which one fit my story best. First, I went back and added the Final Echo to each, so I’d know if it fit the theme/plot/characters well enough to carry through the whole story. In other words, I double checked my ideas about the story, my intentions.

Then I asked these questions of each opening:

- Which sets the tone I want?

- Which sets the emotional problems?

- Which sets the themes?

- Which one sets up the stakes as very high?

Results of Opening Images Writing Exercise

I found several good images that took me in new and different directions than I’d previously been trying—and that’s exciting.

- Warning conch shell – warning comes true, all Mer sick.

- Jake as toddler scared by octopus-like creature un-camouflaging – Watches old Risonian documentary and realizes that Earthlings are complicated.

- Dr. Max lowers a patient into the water and goes into a foreign world – Jake lifts off in rocket for a foreign world.

- Listens to Em’s cd – gives her a cd when he leaves.

- Jake narrates the globe – a news show narrates Jake’s trip to Rison.

- Jake outswims Earthlings – but realizes he’s just a normal kid on Rison.

Which one did I choose? Actually, several. Because I have a main plot and several subplots, I realized that several of these can work in sequence to open the different subplots.

Sometimes, I approach a story methodically, just doing a writing exercise. This time, I was stuck, and the exercise unstuck me. That was a valuable hour of writing!

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Martina Boone, YA Fiction Giveaways, Plotting, Craft of Writing, Add a tag

I was doing a panel at the fabulous New York City Teen Author Festival last week, and I mentioned that my current writing process includes a short discovery draft rather than a traditional outline. I received several tweets asking about that, so I promised to provide a brief how-to.

My first pass pages (the first read-through of a typeset manuscript) is due today for PERSUASION, so this is going to be very quick and dirty, but that's probably appropriate. The whole point of a discovery draft is to pour the story out.

I'll admit, too, that I used to call the discovery draft an outline. I would start writing it based on the my Plot Complications Worksheet, but I only seem to be able to outline action, so wherever I had to reveal information or have an emotional scene between characters, I had to write the dialogue out to see what would happen.

Long story short (or not, as the case may be) my "outlines" ran thirty to forty thousand words! That sounds crazy, but there are a number of benefits.

- The draft is still short enough to allow for easier analysis after the words have all spilled out.

- I have an opportunity to really discover my characters.

- I don't have to censor myself or worry about editing words as I write.

- I can get the story out in a matter of days or weeks and know whether it is going to work.

- I can easily boil down the discovery draft into a standard synopsis.

- The draft is easy to expand into a full manuscript that's far less messy than a standard first or second draft.

- Snapshot of BEFORE -- a scene or two that introduces the main character within her current environment, shows us who she is, what she dreams of, what she is up against, and also suggests what she needs to change.

- Jumpstart for Action -- also called the "inciting incident," the jumpstart is the event that will (in the next section) lead to a decision to aim for change. This sets the story goal, and the jumpstart is where you first get to show whether you are going to have a reluctant protagonist or an active one. Is your character the one who discovers that change is necessary and goes after it because she has set a goal for herself? Or is she pushed into change by outside forces or other characters?

- New Direction and No Going Back -- this is the first turning point, where the character is now aware that change is necessary because she cannot live in the status quo and she must do whatever is necessary to achieve the goal that was revealed in the jumpstart. This is also where we first see that she understands (or thinks she understands) the stakes and the consequences for failure. In making the decision, she demonstrates that what she has encountered has altered her perception of herself and her world in some way, so that she takes some action that she would not have taken before, and that action is irrevocable.

- Testing the Waters -- Having crossed the point of no-return so that she cannot extricate herself without dire consequences, the protagonist has to keep going. Step by step, she works toward the goal, meeting helpers and mentors who will assist her, meeting antagonists and minions who will work against her, and amassing knowledge that will bring her closer to her goal.

- The Big Twist -- At the midpoint of the story, what the protagonist thought she knew is suddenly turned on its head. The goal proves to have been only part of what is necessary, or it proves to be a false goal, or the situation is far more dire than the protagonist originally thought. But there's no way that she can get out of it now.

- False Hope and Disaster -- Despite the added complications, the protagonist thinks she has a chance to win and wrap things up. Her plan is lining up nicely, she's almost there, but oops. Not so fast. The antagonist or forces working against her prove to be far more powerful and complicated than she expected.

- Overcoming Deep Despair -- Having pretty much ruined everything, the protagonist wallows in despair and sees no way out. Before she can find a real solution, she has to get through the emotional black moment that pushes her into the character change she will need in order to finally achieve success. This is the crucible in which her new (winning) character is forged and she finds the strength within herself to keep on fighting.

- The Battle Royale -- The final battle between the protagonist and the forces allied against her. She must summon everything she has, every internal strength and external weapon. Will she succeed? Partially succeed? Lose but live on to fight another day?

- Cleaning it Up -- What happens after the battle? What are the consequences and the remaining steps to be taken after the big bad has been defeated or your protagonist has failed? Here's where you wrap up all the loose ends and minor plots.

- Snapshot of AFTER -- What does the world look like with the Big Bad gone? What is life like for your protagonist in this new world and how is this a change from the snapshot of BEFORE? This is where you get to show your audience what "happily ever after," "more work to do," or "damn, I've really screwed this up" looks like for your protagonist.

Hopeless romantic Isla has had a crush on introspective cartoonist Josh since their first year at the School of America in Paris. And after a chance encounter in Manhattan over the summer, romance might be closer than Isla imagined. But as they begin their senior year back in France, Isla and Josh are forced to confront the challenges every young couple must face, including family drama, uncertainty about their college futures, and the very real possibility of being apart.

Featuring cameos from fan-favorites Anna, Étienne, Lola, and Cricket, this sweet and sexy story of true love—set against the stunning backdrops of New York City, Paris, and Barcelona—is a swoonworthy conclusion to Stephanie Perkins’s beloved series.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Blog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Girls of Gettysburg, historical fiction, Doctor Who, plotting, planning, Add a tag

|

| http://morguefile.com/ |

Historical fiction is the coming together of two opposing elements: fact and fiction. The controversy is grounded in conveying the ‘truth’ of history. Other popular genres have distinct rules that govern basic premises. Dystopian fiction, for example, features a futuristic universe in which the illusion of a perfect society is maintained through corporate, technologic, or totalitarian control. Using an exaggerate worse-case scenario, the dystopian story becomes a commentary about social norms and trends.

But, historical fiction defies easy explanation. For some, historical fiction is first and foremost fiction, and therefore anything goes. Others condemn the blending of invention with well-known and accepted facts, and consider the genre a betrayal.

Perhaps a better way to understand the genre is to take a lesson from The Doctor. Yes, that Doctor: “People assume that time is a strict progression of cause and effect…but actually, it’s more like a big ball of wibbly wobbly, timey wimey stuff.” Perhaps the same thing can be said of plot and the historical fiction.

In historical fiction, setting is usually considered ‘historical’ if it is at fifty or more years in the past. As such, the author writes from research rather than personal experience. But as an old turnip, my personal history dates back to the years prior to Korean War. The Civil Rights Movement, the Freedom Riders, the Bay of Pigs, the JFK Assassination, the Landing on the Moon, and the first Dr. Who episode are not some fixed points in history but a function of my experience. Yet, for the last generations, these are often just dates in a textbook. And the plot is a linear expression that begins on a certain date. The award-winning book, The Watsons Go to Birmingham by Christopher Paul Curtis (1995), depicting the Birmingham, Alabama church bombing of 1963, is often listed as historical fiction. Yet I remember vividly watching the events unfold on my parents’ black and white television.

Defining the ‘historical’ in 'historical fiction' is a bit wobbly, depending upon the age of the

|

| http://morguefile.com/ |

Historians work within a broad spectrum of data-gathering, gathering volumes of primary sources coupled with previous research. They use footnotes, endnotes, separate chapters, appendixes and other textual formatting to clarify their observations. Plotting and planning resemble Vinn diagrams and flowcharts, looking similar to the opening credits of Doctor Who as the Tardis moves forward and backward in time. But the artistic nature of historical fiction presents several challenges in books for children. Events must be “winnowed and sifted”, as Sheila Egoff explains, in order to create forward movement that leads to a resolution. Authors choose between which details to include, and exclude, and this choice is wholly dependent upon the character’s goal. More important, resolution rarely happens in history. The same with happy endings. Because of the culling process, critics often claim that historical fiction is inherently biased.

Yet, nothing about history is obvious, and facts are often open to interpretation. Once upon a time, it was considered factual that the world was flat, that blood-letting was the proper way of treating disease, that women were emotionally and physically incapable of rational thought. In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, but he didn’t discover America. In fact, some would say he was less an explorer and more of a conqueror. History tends to be written by those who survived it. As such, no history is without its bias. The meaning of history, just as it is for the novel, lays “not in the chain of events themselves, but on the historian’s [and writer’s] interpretation of it,” as Jill Paton Walsh once noted.

Some facts, such as dates of specific events, are fixed. We know, for example, that the Battle of Gettysburg occurred July 1 to July 3, in 1963. The interpretations of what happened over those three days remains a favorite in historical fiction. My interpretation of the battle, in Girls of Gettysburg (Holiday House, August 2014), featured three perspectives that are rare in these historical fiction depictions: the daughter of a free black living seven miles north from the Mason-Dixon line, the daughter of the well-to-do local merchant, and a girl disguised as a Confederate soldier. The plot weaves together the fates of these girls, a tapestry that reflects their humanity, heartache and heroism in a battle that ultimately defined a nation.

Critics and researchers can be unrelenting in their quest for accuracy. The process of writing historical fiction, like researching history itself, is neither straightforward nor a risk-free process. As the Doctor tells his companion, and in so doing reminding everyone, through those doors...

“… we might see anything. We could find new worlds, terrifying monsters, impossible things. And if you come with me... nothing will ever be the same again!”

Bobbi Miller

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Theme, Story Structure, Character Development, World Building, Plotting, Craft of Writing, GMC, Revision and Editing, Add a tag

Finally -- don't forget our new monthly Ask a Pub Pro column where you can ask a specific craft question and have it answered by an industry professional. So, get those questions in! Or, if you're a published author, or agent, or editor and would be willing to answer some questions, shoot us an email as well!

Craft of Writing: Best Craft Tips from 2014, part A

Character Development:

Whenever writing a character, always keep one question foremost in mind: what is this character’s motivation? What does this character want? Characters drive stories, and motivation drives character. So that basic motivation should never be too far from the character’s thoughts. What does this character want and what is he or she doing in this scene to get it? It’s almost a litmus test for the viability of a scene. If your character isn’t doing something to get closer to what he or she wants, then you should be asking yourself if the scene is really necessary.(from Using Soap Operas To Learn How To Write A Character Driven Story by Todd Strasser on 2/11/14)

Plot Element (A Ticking Clock):

|

| from sodahead.com |

The clock is mainly a metaphor. You can use any structural device that forces the protagonist to compress events. It can be the time before a bomb explodes or the air runs out for a kidnapped girl, but it can also be driven by an opponent after the same goal: only one child can survive the Hunger Games, supplies are running out in the City of Ember....Only three things are required to make a ticking clock device work in a novel:

-- Clear stakes (hopefully escalating)(from The Ticking Clock: Techniques for the Breakout Novel by Martina Boone on 5/20/14)

-- Increasing obstacles or demand for higher thresholds of competence

-- Diminishing time in which to achieve the goal

World Building (Details):

Whenever you have an opportunity to name something or to get specific about a seemingly random detail in your story, do it. Don’t settle for anything vague or halfway. Be concrete. You never know when one of these details might come in handy later. They’re like tiny threads that you leave hanging out of the tapestry of story just to weave them back in again later.(from Crafting A Series by Mindee Arnett on 1/28/14)

Editing:

“Write without fear

Edit without mercy”

Your first draft should be unafraid. Personally, I’m a planner, but you don’t have to be; I know published authors who aren’t. The important thing is that you embrace the flow of creation and let the story and its characters live. Don’t judge at this point. Write until it’s done.

Once you have that first draft in place, set the story aside for a few weeks, then take off your writing-hat – with all its feathers and furbelows – and don your editing-hat instead. The hat your inner editor wears is stark. No-nonsense. Maybe a fedora.(from Edit Without Mercy by L.A Weatherly on 1/7/14)

GMC:

Even less likeable characters are readable and redeemable so long as they are striving for something they desperately care about. One of the basic tenets of creating a powerful story is that the protagonist must want something external and also need something internal one or both of which need to be in opposition to the antag's goals and/or needs. By the time the book is over, a series of setbacks devised by the antag will have forced a choice between the protag's external want and that internal need to maximize the conflict. The protagonist must react credibly to each of those setbacks, and take action based on her perception and understanding of each new situation.(from Use Action and Reaction to Pull the Reader Through Your Story by Martina Boone on 5/2/14)

|

| from pixshark.com |

Theme:

Theme is important when writing. It can be one of the things that puts the most passion into your work. What is it you are really trying to say with this book? You don’t have to know before you start writing. Heck, you don’t even have to know while doing the first revision. But as you go over your manuscript again—and again—you will see things popping out at you. Tell the truth. Dreams matter. Work together. Listen to your own heart. Those are the things that make us fall in love with literature. Once you begin to notice these repetitions (or if you know what you want to say from the start) the real fun begins, because you begin to see all kinds of beautiful ways to make it evident. Symbolism and dialogue and imagery.(from Write What You Love and Stay True To Your Passion by Katherine Longshore on 6/20/14)

Story Structure:

On Prologues:The point I’m trying to make is that you should always strive to be confident in every page, to the point where you should never need a crutch like a prologue. Instead, the beginning needs to be amazing. Not necessarily adrenaline-filled, not necessarily action-oriented. Just damn good. Every page of your book should be, at the very least, strong and interesting writing, and your opening should have the tangible hooks of the ‘problem’ we feel in this book, even if they are only tugging ever so gently. If you have a prologue its worth examining the real page one and making it stronger, finding your real beginning, having faith in your book and your writing. If it doesn’t hold up, prologue or no, the book won’t work.(from An Agent's Perspective on Prologues by Seth Fishman on 2/24/14)

On story structure and finding the heart of the story:

As a novelist, I have to be both mother and master of my imagination. Story structure is what both of those roles rely upon—structure nurtures, protects, rules and drives the raw imagination. Months into working on Willow, the other characters began to want to have voice in different ways that the original epistolary form would not have allowed. Although I was confident in the characters, I had to also have confidence in my ability to tap into my imagination and structure it so that the soft, intangible electric energy of the original idea or the heart of the story (what Turkish author Orhan Pamuk calls “the secret center” of the novel) are bolstered and illuminated. Structure is always what I go back to when I’m feeling panic or insecurity.(from Wonder Woman's Invisible Jet of Creativity by Tonya Hegamin on 3/28/14)

-- Posted by Susan Sipal

Blog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Poetry Friday, plot, poem, Plotter, plotting, New Year's, Add a tag

.

Howdy, Campers!

Happy Poetry Friday! A poem by Paul Bennett and the link to Tabatha's Poetry Friday post are below.

In TeachingAuthors' opening round for 2015, we are each asking ourselves, "What Are We 'Plotting' for 2015?"

Mary Ann started us out, sharing how she does or does not plot."Planning and plotting are not the same thing," she writes. "Plotting is knowing what happens first, then next, then next and at the end. I never know more than one of those things before I start writing. I've stopped worrying about it."

Thank you, Mary Ann. I haven't a clue how to plot. When I sit down to write, I'm never sure if I'm starting a poem, a song, a verse novel or a picture book. I might be inspired by a color or a phrase from the news. Of course I knew not everyone plots their stories methodically, but it's great relief to be reminded of this!

|

| A group photo of the TeachingAuthors. from morguefile.com |

For example, until recently, I would say I'm fairly disciplined. I've been writing a poem every day since April 1, 2010 (1,743 poems), I brawl with L.A. traffic every two weeks to meet with my marvelous critique group, I write in amiable silence with three or four other writers weekly, and I have a goal or two tucked away in my writer's smock--a couple of picture books, a novel in verse, a collection of poetry, a Pulitzer Prize.

But when my mother began to fade, particularly this last year, it was all I could do to hold onto my writer's smock. Why? Partly because of the increased responsibility, and partly because of the foggy lethargy which set in.

|

| Yeah...kinda like this. from morguefile.com |

I still write a poem a day, though.

So, What am I Plotting in 2015? Nothing.

Well, writing a poem a day. But beyond that? I haven't a clue.

I'm reading Loving Grief by Paul Bennett, a book in brief chapters, each of which ends in a poem, written after the death of his wife. In the chapter, Coming to a Stop, he writes that the three times over a period of months his legs would no longer carry him forward. He stopped. On a street, in an airport, on a hiking trail. Later, he wrote, "those incidents of coming to a stop, those moments of stillness, struck me as early invitations from deep within myself to start new."

Here is the poem which ends that chapter:

Well. I was going to post the poem, until I read the copyright page (oops) which states that I cannot post it without permission. So I won't.

What I will do is to post my own poem about stopping in my life. Please note that each person experiences a death uniquely. I don't feel as if I'm in deep grief right now. Still:

STOPPING BY THE WOODS

by April Halprin Wayland

No snow.

No woods.

But I pause.

To hear the hawk.

To breathe my breath.

To hold this stone.

Alone.

poem (c) 2015 April Halprin Wayland. All rights reserved.

I think I'm listening for the music to cue my next step.

I'll be ready.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird?)

Blog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Mary Ann Rodman, pre-writing, research, plotting, planning, Add a tag

Happy New Year, readers. I hope you had a wonderful holiday season that included reading some of our favorite books from December. (Too much to hope that much writing went on. At least not at my house.)

So we are starting off 2015 with a discussion of plotting a story.

Uh-oh. Houston, we have a problem.

I don't plot my stories. Ever, So if you are hoping to learn how to plot in this post, you can stop reading now. One of the other TA's will tell you everything you need to know in the following weeks.

I'm here to tell the rest of you still reading, it's OK to not plot.

I have visceral reaction to anything requires plotting. Anything that has to be done in specific sequential steps, sends me over the edge. Cooking, math, putting anything together with instructions. I'm awful at all of those things. A couple of years ago, when educational testing discovered that my daughter has the same difficulty I learned this had a name...something like "difficulty with executive reasoning." (Which I suppose means I'll never be President...but I digress.) Sometimes dessert should come first. I almost always read the end of a book first. Working from step A to step B to step C just doesn't work for me. Never has.

I was the student who wrote the term paper first, then the outline. When I was first trying to be a real writer (as opposed to that seat-of-my-pants writer I had been as a teen and young adult) I discovered that some real writers outlined everything they wrote as a first step. This news was so discouraging I stopped writing for several years, because obviously, I had been doing it wrong.

Of course, that didn't last forever. I went back to writing in the same old any-which-way-I can (including out of sequence) method. I did learn a few things. I learned to plan before I wrote.

Planning and plotting are not the same thing. Plotting is knowing what happens first, then next, then next and at the end. I never know more than one of those things before I start writing. I've stopped worrying about it. Planning is knowing what you need to know before you type that first word.

I've mentioned before that writing the minute you get a good idea is not usually the best thing to do. You need to know your characters before you write about them. Who can you write about more successfully? Your best friend or someone you talked to for five minutes at a party? You should know your characters as well as you do your friends before you write about them. That's the first step in my Plan.

Because once a librarian, always a librarian at heart, I think about what I don't know but should for my story. Do I need to research a geographic area? A time period? Speech patterns and slang for a particular area? A disease? A career that I know nothing about? Now is the time to get as many of those answers as you can, before you start writing. What is more frustrating than reaching page 100 and discovering you are missing a chunk of important information. (This will happen anyway, but not as much if you do it upfront.)

This is also the time I pick my Imaginary Reader. Imaginary Reader is the kid I envision reading my book. Imaginary Reader sits next to me while I write. Is IR a girl or a boy, or both? How old? Do they like to read or not? What about my story would interest them? (Actually, I should probably come with my IR first. See? That old executive reasoning problem.)

So if you are not a Plotter, fear not. You can be a Planner. It's worked for me so far.

Posted by Mary Ann Rodman

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Heather Dyer, 3-Act structure, The Hero's Journey, structure, plotting, planning, Joseph Campbell, Add a tag

- Have we established our protagonist in the 'ordinary world' before we turn their lives upside down and make them venture out into the 'unknown'?

- Does our protagonist need to meet a mentor - or gain wisdom from some other external source - in order to help them on their journey of transformation?

- What is the 'dragon' that our protagonist has to face? Is it something or someone outside themselves? Or might the dragon be their own internal 'demons'?

- Does our protagonist face their dragon and reach a point of 'death and rebirth' - which could mean that they have to face their worst fears, relinquish their strongest beliefs or greatest dreams - and change and evolve as a result?

- What is the 'gift' that they get? Is it knowledge, courage or something more concrete?

- Does their new insight or situation then allow them to overcome an old problem, or help somebody else?

Heather Dyer's latest book is The Flying Bedroom.

Blog: Linda Aksomitis (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing Tips, plotting, Run, Historical Fiction for Kids, Add a tag

Plotting a novel sounds easy, doesn’t it? After a […]

The post Plotting a Novel–Difficult Choices Authors Have to Make appeared first on aksomitis.com.

Add a CommentBlog: Dark Angel Fiction Writing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: plotting, Plotting your Novel, Editing Plot, Add a tag

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Plotting, Craft of Writing, Add a tag

From Pantser To Planner: How I Changed My Writing Style by Victoria Strauss

I'm the original pantser. I hate planning and preparing. I'd rather just dive into whatever it is and learn as I go. This has gotten me into some messes, as you can imagine. Deciding to refinish a table and realizing halfway through that you really ought to know how to work with furniture stripper is not a recipe for a happy outcome.

Once upon a time, that was also how I wrote.

Nearly all my books require some degree of preliminary research. But after investing that initial effort, I just want to get on with the actual creation. When I first began writing, I'd start out with a premise, a setting, a compelling image for the beginning, and a definite plan for the end. The rest was a blank canvas that I couldn't wait to fill, discovering the bones of the story as I wrote it.

The problem was that the story never fell organically into place. I'd get interesting ideas for characters and scenes and plot points that sometimes worked, but often took me down irrelevant byways or banged me up against dead ends. Somewhere around the middle of the book (which never turned out to match any of the hazy ideas I might have had at the outset), I would realize that I’d gotten to a place that didn't fit either my planned ending or my already-written beginning, and be faced with the choice of throwing out a lot of material or making major changes to my basic concept. You'd think, since my concept was so nebulous, I wouldn't have a problem tossing it; but those strong beginning and ending images were (and still are) the essence of the book for me, what made me want to write it in the first place. I could never bring myself to abandon them.

In the end I always managed to pull it together. But it was exhausting and frustrating to do so much backtracking and re-writing, and with each book the process seemed to become messier. By my third novel, I felt that I was doing more fixing than creating--and if you do too much fixing, the seams start to show. Writing by the seat of my pants clearly wasn't working for me. I realized that if I wanted to continue with my writing career, something had to change.

So I decided to turn myself into a planner. No more pantsing. No more blank canvas. I'd discipline myself to craft my plot in advance, creating a road map to guide me all the way from A to Z.

But how to plan, exactly? Books on how to write offer a plethora of methods. Index cards. Whiteboards. Timelines. Checklists. Worksheets. Character questionnaires. Three-act structure. The Snowflake Method. Yikes.

Outlining (the kind of conventional I.A.1.a. outlining I learned in school) seemed most familiar. So for my fourth novel, that's what I decided to try. It totally did not work for me. It was too terse, too cold, too structured. Too boring.

Next I attempted a chapter-by-chapter synopsis. But that felt too arbitrary--how could I lock myself into a chapter structure before I knew the rhythm of the narrative?--and too choppy. I didn't want to jump from chapter to chapter like hopping across a series of rocks. I wanted the story to be all of a piece: to simply flow.

So I decided just to tell the story from start to finish, imagining myself speaking to a rapt audience in the warm glow of a blazing campfire, with darkness pressing all around. This approach fit me much better. It felt creative; it had flow. I still took wrong turns and stumbled down blind alleys--but it's a lot easier to fix those in a synopsis than in a manuscript. And when I was done, I had a clear path from my blazing beginning image to the ending I was dying to write.

For reasons that had nothing to do with planning, I never did finish that fourth novel. But I've used this basic method ever since. First I figure out the core of the book: premise, setting, opening and conclusion. Then I build a bare-bones road map in my head, establishing the story arc and the main characters, making sure I can travel all the way to the end without getting lost in the middle. Then I write a synopsis, fleshing out the story bones and adding detail to plot and characters, but not drilling down to the level of individual scenes (unless an image really grabs me). For a 100,000-word book, my synopses generally run about 10-12 single-spaced pages. I also do brief character sketches as I go along.*

Once I'm done with all this preparation, I file it away and never look at it again. This may seem like a waste of effort. But writing from memory, without paying slavish attention to a plan, gives my pantser's soul the flexibility it needs, allowing room for change and inspiration, for those "aha" moments that, for me, are the most exciting part of writing. Because I do have a plan, however--because I've fallen into most of the holes and backtracked out of most of the dead ends in advance--I don't veer off track the way I used to; and where I do diverge, it's productive rather than destructive. My finished books nearly always differ in significant ways from my initial road map. But the important plot turns don't change.

This melding of planning and improvisation is the best balance I've found between the creative license I crave and the structure I need.

Changing my approach to writing has also taught me something important about writing itself: there is no "correct" or "best" way of doing things--only what's best for you. I can't count the number of times I've heard that planning destroys inspiration, or that only hack writers plan, or that real creativity is letting the story find you, not the other way around. Conversely, most of the highly-recommended planning techniques I tried felt too constraining or too boring.

Trial and error is the key. Don't be afraid to experiment. If something isn't working for you, don't be afraid to abandon it and try something new. It took me a long time, and many mistakes, to figure out my ideal method. But eventually I found my way.

You will too.

* If worldbuilding is needed, as with my fantasy novels, I work that out in between the in-my-head planning and the written synopsis (I've written about my worldbuilding method here: http://www.victoriastrauss.com/advice/world-building/).

About The Author

Victoria is the author of nine novels for adults and young adults, including the Stone fantasy duology (The Arm of the Stone and The Garden of the Stone) and Passion Blue and Color Song, a pair of historical novels for teens. In addition, she has written a handful of short stories, hundreds of book reviews, and a number of articles on writing and publishing that have appeared in Writer’s Digest, among others. In 2006, Victoria served as a judge for the World Fantasy Awards.

Victoria is the co-founder, with Ann Crispin, of Writer Beware, a publishing industry watchdog group that provides information and warnings about the many scams and schemes that threaten writers. She received the Service to SFWA Award in 2009 for my work with Writer Beware.

Victoria lives in Amherst, Massachusetts.

Website | Twitter | Goodreads

ABOUT THE BOOK

Color Song

Color Songby Victoria Strauss

Hardcover

Skyscape

Released 9/16/2014

By the author of the acclaimed "Passion Blue," a "Kirkus Reviews" Best Teen Book of 2012 and "a rare, rewarding, sumptuous exploration of artistic passion," comes a fascinating companion novel.

Artistically brilliant, Giulia is blessed?or cursed?with a spirit's gift: she can hear the mysterious singing of the colors as she creates them in the convent workshop of Maestra Humilit?. It's here that Giulia, forced into the convent against her will, has found unexpected happiness and rekindled her passion to become a painter?an impossible dream for any woman in 15th century Italy.

But when a dying Humilit? bequeaths Giulia her most prized possession?the secret formula for the luminously beautiful paint called Passion blue?Giulia realizes she's in danger from those who have long coveted the famous color. Faced with the prospect of a life in the convent barred from painting as punishment for keeping Humilit s secret, Giulia is struck by a desperate idea: What if she disguises herself as a boy? Could she make her way to Venice and find work as an artist's apprentice?

Along with the truth of who she is, Giulia carries more dangerous secrets: the exquisite voices of her paint colors and the formula for Humilit s Passion blue. And Venice, she discovers, with its gilded palazzos and masked balls, has secrets of its own. Trapped in her false identity in this dream-like place where reality and reflection are easily confused, and where art and ambition, love and deception hover like dense fog, can Giulia find her way?

This stunning, compelling novel explores timeless themes of love and illusion, gender and identity as it asks the question: what does it mean to risk everything to pursue your passion?

Purchase Color Song at Amazon

Purchase Color Song at IndieBound

View Color Song on Goodreads

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Anna Wilson, teenagers, structure, plotting, Xbox, Penny Dolan, X Factor, Add a tag

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: structure, plots, plotting, planning, character motivation, Heather Dyer, 3 Act, 3-Act structure, changing characters, Mary Caroll Moore, pantsers and plotters, pantsters, w-plot, Add a tag

I’ve always been an awful plotter. I write intuitively, going down dozens of blind alleys before (sometimes) finding my way out into the sun. I’ll admit, though, that once written, my stories do all follow the generally accepted 3-Act story structure.

http://howtoplanwriteanddevelopabook.blogspot.co.uk/

Blog: An Awfully Big Blog Adventure (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character, sequel, plotting, turkey, blackberries, Breaking Bad, Add a tag

Blog: Teaching Authors (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: picture books, plotting, planning, Jill Esbaum, Add a tag

A writer puts her/his heart and soul into crafting a picture book story. Over a period of weeks or months, she sweats and strains to get every little element exactly right. Finally, it's ready. The main character is enormously appealing. The language sings. The storyline crackles. Not one word is unnecessary or out of place.

She sends it off, and ... an editor agrees. Woo-hoo! Break out the bubbly!

A fabulous illustrator brings the story to exquisite life. The writer can't believe her luck. Flash forward two or three (or five) years, and she's holding her story – this perfect story – in her hands, a picture book at last.

Then ... more good news. Glowing reviews. STARS. Additional printings. Big sales. Her book soon grows more popular than she dared to dream it could, and then ...

Her editor asks for a sequel. I imagine this request elicits astonishment and elation (and perhaps the eensiest shiver of terror).

I can only imagine, since it hasn't happened to me yet. But I have been asked (not contracted) to write a picture book sequel. For me, the toughest part was beginning. How much should I refer back to the first book? SHOULD I refer back to the first book at all? Well, I figured it out. But it made me wonder what other authors consider the toughest thing about writing a sequel.

To find out, I asked three of them I admire. Here's what they had to say.

Jennifer Berne, on writing Calvin, Look Out! (illustrated by Keith Bendis, coming Aug. 5th, 2014 – eek, that's tomorrow!), sequel to Calvin Can't Fly (Sterling Publishing, 2010):

"Writing the sequel was easier because I had come to know Calvin, his way of thinking, his way of talking, his passions and frailties. But the sequel was harder because I didn't want it to be too imitative of the original, yet it did need to feel connected and like a natural next adventure.

"I hope I succeed in meeting all my goals for Calvin, Look Out! Only time and my wonderful young readers will tell."

Bonny Becker, on writing A Birthday for Bear (illustrated by Kady MacDonald Denton) and other sequels to A Visitor for Bear (Candlewick Press, 2008):

"The biggest challenge without question is the problem of keeping the stories fresh. It's easy to think of situations that will frustrate Bear, but I don't want the escalation of the problem or the resolution to be too predictable. And I've tried to subtly move Bear's story along. His friendship with Mouse deepens and he's slowly coming out of his shell--in a way. At least, in the latest book, A LIBRARY BOOK FOR BEAR, Bear finally gets out of his house and there are actually other creatures in his world that he interacts with.

"Each sequel is easier in some ways and harder in others. I know these characters and their world better with each story, but, as mentioned, coming up with fresh situations and reactions doesn't get easier! It's also tempting to get lazy about it all--not work as hard for fresh language and gestures and such. So I work hard to reference back to earlier books--for example, Bear uses the skates he got in A BIRTHDAY FOR BEAR to get to the library and the humor works better if you know that Bear always ends up shouting--but I also want each book to be strong on its own.”

Pat Zietlow Miller, on writing Sophie's Seeds (currently in the pipeline), sequel to Sophie's Squash (Schwartz & Wade, 2013):

"My biggest challenge was that I had never imagined Sophie having a sequel. So I really had to start from scratch and ponder what she might do next.

"Plus, Sophie's Squash had been so well received that I felt a certain amount of pressure to do an equally good job. I hadn't ever felt that pressure before because I'd always written without anyone expecting it and waiting to see what I'd done.

"So writing Sophie's Seeds took longer and was a bit more painful, but I'm very happy with where we ended up and that Sophie got to have another adventure."

Count me among the biggest fans of Calvin, Bear & Mouse, and Sophie. Here's to their continuing stories. *clink*

Jill Esbaum

P.S. You can now find me on Twitter @JEsbaum

Blog: Darcy Pattison's Revision Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: novel, scene, plotting, write, revise, action, Novel Revision, plot points, off-stage, Add a tag

|

|

|

Here’s a common problem that I see in first drafts: the main action has happened off-stage.

Think about Scarlett O’Hara and the other southern women sitting at home waiting; in an attempt to avenge his wife, Frank and the Ku Klux Klan raid the shanty town whereupon Frank is shot dead. But the raid takes place off-stage.

Or, think about times when a weaker character stays home, while the adventurous character is off doing something. Sports stories are hard when the POV character is watching the on-field action.

This can be a real trap for children’s novels if an older sibling or parent is doing something fun/exciting/scary/etc off stage.

Another challenging situation is when a bully is planning something and the POV victim is just trying to avoid that.

Or, maybe you’ve planned a great scene, and the main character is present, but you don’t write that scene. Instead, what you write is something like this: “The next morning, Elise lay in bed and went over the previous night in her head.”

No. That doesn’t work!

Does this always need to be changed? No. But it’s a major problem and challenge as you revise. Here are some tips.