new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Online Resources, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 43 of 43

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Online Resources in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Michelle,

on 4/13/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

library week,

scavenger hunt,

onling,

ORO,

Oxford Reference,

Library,

quiz,

History,

Reference,

Education,

Current Events,

oxford,

A-Featured,

Online Resources,

online,

World History,

week,

Add a tag

Justyna Zajac, Publicity

In honor of National Library Week 2009, OUP will be posting everyday to demonstrate our immense love of libraries. Libraries don’t just house thousands of fascinating books, they are also stunning works of architecture, havens of creativity for communities and venues for free and engaging programs. So please, make sure to check back in all this week and spread the library love.

To kick off Library Week, OUP is providing everyone with free access to Oxford Reference Online (ORO) and to encourage you to check out we have provided the scavenger hunt below. Use ORO to find the answers. Let us know what you found out in the comments. Just go here and log in with user: nationallibraryweek and password: oxford. Let the games begin! Be sure to visit again this afternoon when we post the answers.

1. Who was the founder of the Junto Club, predecessor to the Library Company of Philadelphia, created in 1731 and considered to be America’s first public library?

2. What 18th century English poet said, “The greatest part of a writer’s time is spent in reading, in order to write: a man will turn over half a library to make one book?

3. The library of the Supreme Court of the United States was created by a congressional act in what year?

4. Who was named the first librarian of Congress in 1802?

5. In what city is the Newberry Library located?

6. The Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America began at what academic institution?

7. Under which pope was the Vatican Library established in 1450?

8. The largest research library in Ireland is located at what university?

9. The manuscript division of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C houses White House papers and documents of all Presidents from George Washington through which president?

10. Name two of the three individuals whose private collections formed the basis for the British Museum and Library, founded in 1753.

By: Rebecca,

on 3/20/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Eistein,

march 20,

realtivity,

History,

Science,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Online Resources,

this day in history,

Add a tag

On this day in history, March 20, 1916, Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity. To help you learn more about relativity we turned to The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science, which we found through Oxford Reference Online. The article about relativity below is by J. L. Heilbron.

Relativity, a theory and program that set the frame of the physical world picture of the twentieth century…

…In the thought experiment Einstein often described, an observer on an embankment sees a light flash from the middle of a passing railroad carriage equipped with a mirror at either end. According to relativity, an observer seated at the center of the car would see the light returned from the mirrors simultaneously. But the observer on the embankment would see the flash from the forward mirror after that from the rear: the light has farther to go to meet and return from the forward than from the rear mirror, and the speed of light by hypothesis is the same in both directions. On a ballistic theory of light, the return flashes occur simultaneously for both parties: to the traveling observer, the light has the same speed in both directions; to the stationary one, the speed in the forward direction exceeds that in the opposite direction by twice the speed of the carriage. Further arithmetic shows that holding to the absolute and the relative simultaneously required that meter sticks and synchronized clocks moving at constant velocity with respect to a stationary observer appear to him to be shorter and tick slower than they do to an observer traveling with them. Einstein showed that the form and magnitude of these odd effects follow from the stipulation that the coordinates of inertial systems are related by a set of equations that he called the Lorentz transformation. Hendrik Antoon Lorentz had introduced them as a mathematical artifice to make the principle of relativity apply to Maxwell’s equations of the electromagnetic field… Einstein now insisted that the Lorentz transformation apply also to mechanics in place of what came to be called the “Galileo transformation” that guaranteed relativity to Newton’s laws of motion…Since the Galilean transformation supports the Newtonian expressions for force, mass, kinetic energy, and so on, replacing it required reworking the formalism of the old mechanics. This labor, in which Max Planck and his student Max von Laue played leading parts, produced expressions differing from the Newtonian ones by factors of γ. A new form of Newton’s second law emerged that satisfied the demand of relativity (“remained invariant”) under the Lorentz transformation.

As an afterthought, also in 1905, Einstein argued that energy amounts to ponderable mass and vice versa. The relativistic expressions for the momentum and kinetic energy require that, for conservation of momentum to hold, the mass m of an isolated system of bodies must increase when the system’s kinetic energy E decreases. The increase occurs at a rate (change of mass) = (change of energy)/c2, Δm = ΔE/c2. Einstein thus united the previously distinct principles of the conservation of energy and of mass. From a practical point of view, the equivalence of mass and energy as applied to nuclear power is by far the most important consequence of relativistic mechanics.

Relativity had an enormous appeal to people like Planck, who regarded the surrender of common-sense expectations about space, time, and energy as a major step toward the complete “deanthropomorphizing of the world picture” begun by Copernicus. The mathematician Hermann Minkowski declared in a famous speech to the Society of German Scientists and Physicians in 1908 that “space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.” He interpreted the Lorentz transformation as a geometrical rotation in his four-dimensional space, whose points represented “world events” and whose lines represented the histories of all the particles in the universe. “The word relativity postulate … seems to me very feeble,” he said, “to express the postulate of the absolute world,” that is, Einstein’s theory as geometrized by Minkowski.

Einstein’s compulsion to remove the “all too human” from physics and his desire to overcome the limitation of SRT brought him to a more profound generalization than Minkowski’s. Taking the equivalence of inertial and gravitational masses as his guide, he worked out by 1911 that gravitational forces should affect electromagnetic fields (for example, by giving radiation potential energy) and deduced that the sun would bend the path of a ray of starlight that passed close to it. But the major conquest wrested from the equivalence of the masses was the elimination of gravity: all freely falling bodies in the same region experience the same acceleration because the presence of large objects distorts the space around them and the bodies have no alternative but to follow the “geodesics”—straight lines in the curved space in which they find themselves. In “flat space-time,” without distorting masses, bodies move in inertial straight Euclidean lines. Falling bodies apparently coerced to rejoin the earth under a gravitational force in Euclidean space in fact move freely along geodesics in the local warp in the absolute four-dimensional space-time occasioned by the earth’s presence. By 1915 Einstein had found the mathematical form (tensors) and the field equations describing the local shape of space-time that constituted the backbone of GRT, and had added two more tests: an explanation of a peculiarity in the orbit of Mercury and a calculation of the effect of gravity on the color of light.

By 1910 or 1911 German theorists had accepted SRT and a few physicists elsewhere recognized its importance…Einstein traveled, quipped, became a favorite of newspaper reporters around the world and the bête-noire of anti-Semites back home. He spent the rest of his life, in Berlin and in Princeton, trying to generalize the general by bringing electromagnetism within GRT. But neither his efforts nor those of the few other theorists who thought the game worth the candle managed to reduce electricity and magnetism to bumps in space.

…Although gravity remains outside the unified forces of the Standard Model, the pursuit of the vanishingly small and the ineffably large depend upon GRT for clues to the origin and evolution of the universe…

Today the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography publishes its first print supplement, a volume containing the lives of more than 800 notable figures from British life who died over the four years 2001-2004. It is ‘supplementary’ to the 60 volumes of the Oxford DNB which were published in September 2004 and which included the biographies of nearly 56,000 prominent people drawn from two millennia of British History. In the post below, ODNB Editor Lawrence Goldman talks about the process of choosing who to include.

It is the Dictionary’s job to record the lives of all those who made national history for good or ill, and not to forget those whose contributions went largely unremarked during their lives. The Oxford DNB, as we often say, is not just a roll call of the great and good – prime ministers, bishops, civil servants and diplomats – but a compendium of all those who shaped national life from rock stars to poets and bare-knuckle fighters (look up one, Bartley Gorman).

I’m often asked how we choose the two hundred or so people whom we add to the Dictionary each year. How is the choice made? By what principles? And where does the buck stop? The process is quite arduous, in fact, involving several stages and much consultation. For us, humankind can be divided into 43 categories, all of them professional and vocational from A for archaeologists to Z for zoologists. C is for classicists; G for geologists; P for politicians; s for soldiers. For each of these categories there are a set of advisors, numbering more than 450 in total, who we consult and who provide us with their expert appreciations of the recently deceased and their judgments of their significance in their respective fields. Advisors must remain anonymous so that their judgment can be given unimpaired, but they number many eminent and well-known figures, leaders in their subjects. With the help of one of our research editors, Alex May, we compare and contrast their views, grateful that in most cases they reach a consensus, and use their advice as our guide. In many cases it is clear who deserves an entry in the Dictionary, but when the going gets technical we are glad to rely on the experts.

Nevertheless there are occasions when the Editor has to make the call. We usually end up with about 220 ‘possibles’ and about fifteen of these will be left out. If the choice is between two explorers or two aviators – two of anything, in fact – it is usually possible to decide on the basis of a close reading of obituaries, memoirs, and the comments of the advisors. At such moments we try to weigh up achievements. But how to choose between the competing claims of figures drawn from different fields? And how to weigh in the balance the national importance of say, an act of great heroism lasting all of 60 seconds that won a serviceman the Victoria Cross, or the steady endeavour of a whole career in public service? At such moments I try to project forward and consider whose contributions will last and still seem relevant a generation from now, and whose achievements will have faded and seem insignificant? To second guess the future, trying to imagine its different values and tastes isn’t easy, especially when one is trying to imagine how the different work of a stained glass painter or a potter will fare over the intervening decades. I often hear in my ear the imagined rebukes of a future Editor roundabout 2050: ‘why the devil did he put him in?’ But I have a way of consoling myself at such moments of self-doubt: even my mistakes, I reason, will be of interest to the future, for they will show our descendants what we thought to be important or interesting or relevant in our age and underline that the past really is ‘another country’ in which they did things differently.

1. Tell us a little about your publication credits. If you have none, tell us about the genres you prefer to write, and your current projects.

The Doomsday Mask 2009, The Heretic's Tomb 2007, The Emerald Curse 2006, The Clone Conspiracy 2005, The Sorcerer's Letterbox 2004, The Alchemist's Portrait 2003, The Complete Guide to Writing Science Fiction Volume One 2007 (Contributing author)

2. How

There are so many wonderful online resources for children's writers, but it isn't always easy to work out which ones are worthwhile. Today's hot writing link is to a wonderful list of online resources, compiled by Holly black. What's so great about this list is that Holly has categorised the list so methodically, by using common questions from new writers, and providing the best link or links to

By: Rebecca,

on 10/22/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Sarah Russo,

80,

spacey,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

A-Editor's Picks,

birthday,

event,

Online Resources,

oed,

dictionary,

Add a tag

Sarah Russo, Associate Publicity Director

Like most postcards, this post comes many days after I have returned from Oxford and the 80th anniversary celebration of the Oxford English Dictionary. My last post left off on Monday after our lunch at the Eagle and Child Pub where Simon Winchester and Ammon Shea joined us for fish and chips and pints of warm English beer (mine was a half pint, I didn’t even know they came in half sizes, shows how under-traveled I am!).

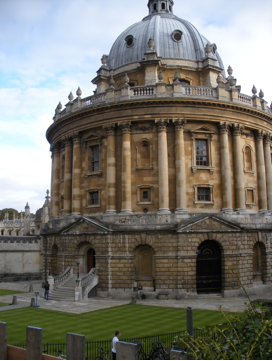

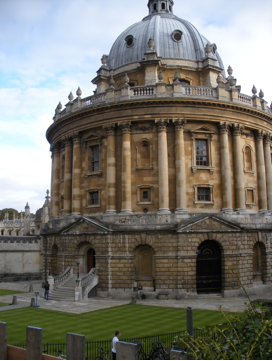

The rest of the afternoon, was spent touring the city. First with the journalists and a professional tour guide who wore a little medallion proclaiming his official status. We took a great tour of the city, hitting several of the colleges (there are 39 in total that make up Oxford University, not to mention nearly 80 libraries!) and spots where they film Harry Potter. We saw some amazing architecture, including the Radcliff Camera:

And the very spot where three martyrs were burned during the Bloody Mary years! Marked by this cobble cross:

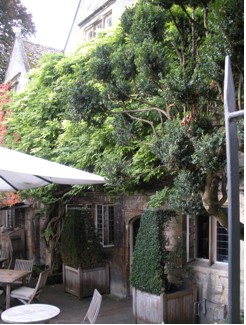

My second tour was a little more interesting when I rejoined Simon Winchester in the courtyard of the Old Parsonage:

I know Simon’s very lovely wife, Setsuko Sato, from her years as a producer for NPR’s Talk of the Nation. So over a few meetings Simon and I have gotten to be friends. As 5 o’clock rolled around we went out for a stroll through the park that borders the colleges of Oxford. On our walk we started to pass through Simon’s college. St. Catherine’s is the newest college of Oxford, founded in 1962 by the historian Alan Bullock.

St. Catz has a decidedly different feel from the rest of the colleges at Oxford. It was designed by Danish architect Arne Jacobsen in the modern Scandinavian style with a traditional English layout around a quadrangle. Jacobsen’s designs went further than the design of the buildings, similar to Frank Lloyd Wright; he also designed the cutlery, furniture, and lampshades, everything right down to the finest detail. Simon and I walked into the dining hall, which is nothing like dining halls here in the U.S., the long blond wood tables are lined up in neat rows headed by the table for professors and dignitaries at the front of the room on a low dais. The room was set up for dinner and I would have thought it was a special occasion the way everything sparkled—little did I know that it was a special occasion—but it seems they set everything up this way every night, with a dozen pieces of silverware and crystal to match.

After just slightly scaring the setup staff, as Simon had me sit in one of the ergonomic and utterly gorgeous high-backed chairs, we decided to take a detour so Simon could say hello to the Master of the college, Professor Roger Ainsworth. Simon found Roger chairing that night’s special event, a lecture by none other than America’s own Kevin Spacey! Kevin Spacey is this year’s Visiting Professor of Contemporary Theater. As odd as this may seem, Mr. Spacey has been the Artistic Director of the Old Vic Theatre in London since 2003 when it announced that it would once again become a producing theater. After the lecture Simon, and I by extension, were invited to cocktails and were introduced to Kevin Spacey. I had the slightly abashed pleasure of being introduced to Mr. Spacey as “a fellow American.” Suffice it to say, it was a great surprise and a definite highlight of the trip. We were able to chat with him for a few minutes and talked about how he has been living in London’s South End for the past six years.

All of this made Simon terribly late for his dinner with his fellow panelists (Ammon Shea, John Simpson–Chief Editor of the OED, and Lynda Mugglestone–Vicegerent, Fellow in and Tutor in English, Pembroke College), for Wednesday night’s main event at the Bodleian Library, so we rushed back. I ended day one in Oxford with dinner at the Old Parsonage, a table for one that was quickly filled by passersby who stopped to chat while I ate. An altogether perfect end to Alice’s first day in Oxford.

Day 2:

Tuesday began much like yesterday: coffee, toast, that sweet, sweet marmalade again and then the mad rush.

This is the real OED day: in-depth sessions about how the dictionary is put together, where its future lies (web or print), how long the new revisions will take to finish. Journalists received answers to all of these questions and more (you can read some reports both here: Maud Newton and here: Barbara Wallraff. The decision on whether there will be another print edition seems to be the one that people are most fascinated with. The New York Times Magazine earlier this year wrote of the demise of the print edition of the OED which has everyone aghast that the giant volumes may cease to exist. But Robert Faber, the Editorial Director of the OED, put most of these unfounded fears to rest. The revision of the OED is nowhere near complete. It could take another ten years, maybe fifteen to complete this round of revisions. That said, they honestly don’t know what the publishing world will look like in fifteen years but the OED hasn’t been out of print since the second edition was published in 1989 so in my mind that means the chances are fairly good for the print edition of OED 3. We also learned that each year revisions add the equivalent of one volume of information to the OED online which could mean that there will be some 30 to 40 volumes in the next edition. That is truly amazing!

So after the presentations, the journalists got to break into one-on-one groups with the editors of the different departments of the OED: new words with Fiona McPherson, etymology with Philip Durkin… This is where Simon Winchester’s inspiration for an op-ed on the change in meaning of “subprime” came from. While the journalists were getting into the nitty gritty of the OED I explored the OED library. Have you ever seen the condensed edition of the original OED? It literally has four pages of the giant volumes printed micro size to a page. It comes with a magnifying glass!

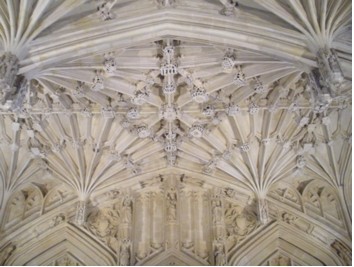

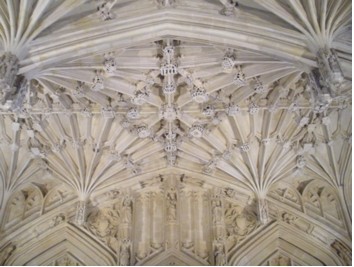

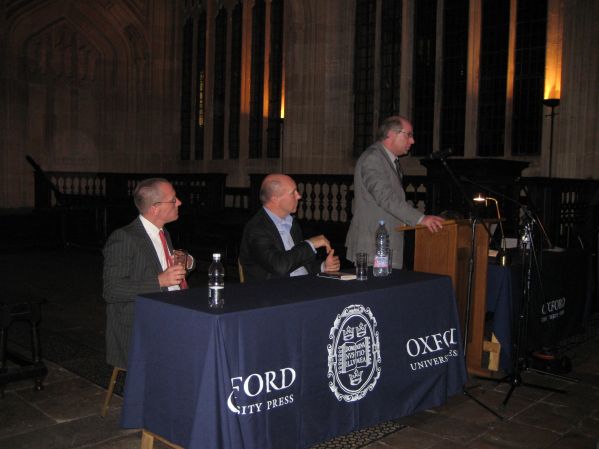

The day culminated with the public event in the Bodleian Library. Simon Winchester spoke about the history of the OED, John Simpson spoke of the present and future, and Ammon Shea talked about his experience reading the volumes from cover to cover. Questions ensued at the end for Ammon and it really was amazing to hear all of the parts condensed into an hour presentation. All of the most interesting bits of the past two days for a group of word lovers gathered under this amazing ceiling of the Bodleian:

But you don’t have to travel to England to get a glimpse into the OED. There will be events in the U.S. as well:

Events:

The Century Club (Members/Invite only) event will be a panel discussion on October 22nd at 6 pm featuring:

o Simon Winchester, author/historian

o Ammon Shea, author of Reading the OED

o Jesse Sheidlower, OED editor at large

The Harvard Bookstore event will be a panel discussion held on November 13th at 5:30 pm at the Brattle Theatre featuring:

o Jesse Sheidlower

o Ammon Shea

o Simon Winchester

o Barbara Wallraff, Word Court columnist in The Atlantic

The Philadelphia Free Library event will be a panel discussion on November 18th from 7:30 to 9 pm and will feature:

o Jesse Sheidlower

o Ammon Shea

o Barbara Wallraff, Word Court columnist, Atlantic Magazine

The Harvard Club of NYC event will be a discussion on March 4, 2009 featuring:

o Jesse Sheidlower

o Ammon Shea

ShareThis

By: Kirsty,

on 10/16/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

maverick,

odnb,

victoria clafin woodhull,

woodhull,

beecher–tilton,

halves,

History,

Biography,

Reference,

UK,

Politics,

American History,

president,

A-Featured,

Hillary Clinton,

Online Resources,

victoria,

Add a tag

Though she ultimately lost out to Barack Obama in the race for the Democratic Party nomination for President of the USA, there was much to be excited about, I think, in the fact that Hillary Clinton was running for the top job. After all, how rare for a woman to climb the political ladder to such heady heights. But she wasn’t the first. Here, Philip Carter, Publication Editor for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, introduces an excerpt from the biography of Victoria Clafin Woodhull. She was the first woman to run for the US presidency, in 1872, and was, one might say, the original presidential maverick. I can tell you, it really does make for fascinating reading. Over to Philip…

For 50 years, until her death in 1927, Woodhull lived in England where—as in the USA—she attracted considerable attention for her ambition and unorthodox lifestyle. The Oxford DNB biography, written by the dictionary’s editor Lawrence Goldman, brings together the two halves of Woodhull’s remarkable transatlantic life. The following is an extract from her biography which can be read in full either on the ODNB website, or can be downloaded as a podcast.

The sisters faced criticism and opprobrium in England as in America. Henry James’s novella The Siege of London (1882) was read by many as a fictionalized account of Victoria Woodhull’s campaign to woo and win her third husband. Angered by constant public references to her past, in February 1894 Victoria Woodhull Martin and her husband brought an action for libel against the trustees and the librarian of the British Museum for making available to readers two pamphlets in the library on the Beecher–Tilton affair that were admitted to be libels against her….

… Featured in Country Life (14 June 1902), she engaged in local educational and rural philanthropy, but ceased any involvement in women’s suffrage or purity campaigns. A particular enthusiasm was for a scheme to develop a women’s agricultural community at Bredon’s Norton, renting out small plots of land to allow women to learn the rudiments of farming. She was one of the earliest motor car owners in Britain, driving a Mercedes Simplex and undertaking motoring tours in Britain and France, and was a founder member of the Ladies Automobile Club (1904). Having long urged that the fourth of July should be celebrated as Interdependence Day, she became a leading promoter of Anglo-American links, active in plans to mark the centenary (December 1914) of the treaty of Ghent….

….[at her daughter’s] instigation, a memorial plaque to her mother was unveiled in Tewkesbury Abbey in July 1943, paying tribute to her as ‘An American citizen long resident in this neighbourhood who devoted herself unsparingly to all that could promote the great cause of Anglo-American friendship’. Victoria Woodhull died an honoured member of her adopted country and community in a life of two quite distinct halves. That she was able to recreate herself so successfully in England after such notoriety and ignominy in America was tribute to her remarkable adaptability and force of personality.

ShareThis

By: Kirsty,

on 10/15/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

john simpson,

History,

Reference,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

ammon shea,

Samuel Johnson,

simon winchester,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

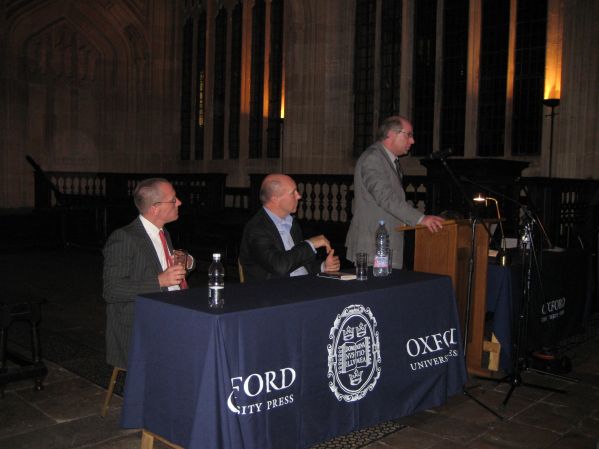

Last night saw the OED 80th Anniversary celebrations culminate in a public panel discussion on  ‘The Oxford English Dictionary: Past, Present, and Future’ at the incredibly beautiful and historic Bodleian Library in Oxford.

‘The Oxford English Dictionary: Past, Present, and Future’ at the incredibly beautiful and historic Bodleian Library in Oxford.

On the panel was OED chief editor John Simpson, historian and author of The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary Simon Winchester, and Ammon Shea, who wrote Reading the OED and who of course needs no introduction to OUPblog readers.

Simon Winchester opened up proceedings with a history of dictionaries, telling us that 1604 saw the first modern  dictionary as we understand them today. In that case, it was a slim book written by Robert Cawdrey called A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues. Snappy, huh?

dictionary as we understand them today. In that case, it was a slim book written by Robert Cawdrey called A table alphabeticall conteyning and teaching the true writing, and vnderstanding of hard vsuall English wordes, borrowed from the Hebrew, Greeke, Latine, or French, &c. With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of ladies, gentlewomen, or any other vnskilfull persons. Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, vvhich they shall heare or read in scriptures, sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues. Snappy, huh?

He then went on to talk about arguably the most famous dictionary (other than the OED obviously!): that by Samuel Johnson. Johnson was known as a bit of a cantankerous fellow, and this sometimes filtered down into his definitions. For example, his famous definition of ‘oats’:

A grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland appears to support the people.

I won’t take offence, promise. Then we heard about the famous OED editors of the late 19th and early 20th century: Herbert Coleridge, Frederick Furnivall (who had to leave the job after it was realised that he was more interested in sculling and well-endowed young ladies), and, of course, James Murray.

John Simpson, today’s OED editor, took us through what happens to an entry and the kinds of information that is needed for the Dictionary. He used the example of ‘lifeboat’ and took us through its history from its first appearance in the first edition of the OED , to moving from being hyphenated (life-boat) to a solid word in 1903, up to the latest evidence of its earliest usage, which will be in the updated entry to go online soon.

Then, to finish the evening, Ammon Shea told us all about reading the OED from A-Z in one year. To read more about the many wonderful words he discovered during that year, then do read his past posts for OUPblog. But I couldn’t agree with him more when he said that there is much emotional content within the Oxford English Dictionary: the poignancy of a word that means ‘to no longer own something, but to wish that you still did’, or a word that means ‘the sound of leaves rustling in the wind’. The OED is, as Ammon said, a “remarkable creature of literature”, which is why I am so happy to have been here for the 80th anniversary celebrations.

Here’s to another 80 years, and many, many more.

ShareThis

By: Kirsty,

on 10/15/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

university of glasgow,

Reference,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

thesaurus,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

In amongst the many fascinating facts and stories around the OED that we have been hearing about during the celebrations, yesterday we also heard about an exciting project that is headed for publication in autumn 2009: the Historical Thesaurus.

Robert Faber, Editorial Director of Scholarly and General Reference, told us that the project has been in progress for decades now at my Alma Mater, The University of Glasgow, and is creating a historical thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary.

It will be organized along thematic lines, and will be publishing in two volumes late next year. The example he used was that people would now be able to find out every word that meant “strong liquor” in the 18th century, which is the kind of thing that will be invaluable for writers, historians and many other people.

Based on the content of the currently in print second edition of the OED, its findings will eventually be incorporated into the OED online.

As a bit of a word geek myself, I’m already looking forward to see this in the flesh (paper?), especially as I remember walking past the Historical Thesaurus office at Glasgow every day for four years on my way to the student union!

ShareThis

By: Kirsty,

on 10/14/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

80th,

weapons of mass destruction,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

Among the many interesting talks from various senior editors of the OED, this morning we had Fiona McPherson from the OED new words team telling us about how a new word is added to the Oxford English Dictionary and the processes they go through to do it.

Fiona and her team collect suggestions for words (or “lexical items”) to be added to the OED in a variety of ways. Sometimes members of the public write in with suggestions, sometimes they come from words being used a lot in the news, or they find them in novels and other writing. They also have a series of dedicated reading programmes. Fiona works with the UK-English Contemporary team. Here, a team of readers scour all types of printed matter from all over the English-speaking world for new words or senses. This can include anything from literature and non-fiction, to TV or radio scripts, or even newsletters; anything, as long as it has a date ascribable to it.

When a word is found, through whichever of those means, that isn’t in the OED and should be, the new words team start with an essentially blank page which they have to fill with a large amount of information such as pronunciation (UK and US), etymology, definition, and a paragraph of quotations showing the word in use. When all this is done, the word is then passed on to the etymology team, who go into more in-depth etymological research.

Often, Fiona said, they find a “new” word isn’t quite as new as they thought. She used the example of the phrase ‘weapon of mass destruction’, which was added to the OED in 2004. She said she was fairly sure that the phrase did indeed go back further than the lead-up to the 2003 Iraq war, and was unsurprised to find evidence of it being in use around the time of the first Gulf conflict in the early 1990s - indeed that was the rough date of the earliest evidence they found for the abbreviated form ‘WMD’. However, she was amazed to find that the examples of the full ’weapon of mass destruction’ kept going back and back until she found the earliest written usage so far:

Who can think without horror of what another widespread war would mean, waged as it would be with all the new weapons of mass destruction?

This was from the Archbishop of Canterbury in The Times. The date? 28 December 1937. Amazing.

Read more about the OED’s 80th birthday celebrations

here.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 10/14/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

celebration,

diary,

Current Events,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

England,

tolkien,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Sarah Russo,

80,

marmalade,

congregate,

parson,

taxi,

Add a tag

The Oxford English Dictionary is 80 and there are celebrations taking place all week in Oxford, England. Sarah Russo, Associate Publicity Director, was lucky enough to travel to Oxford for the celebrations and below is her letter home to us, the poor colleagues still at our cubicles toiling away. Sarah and Kirsty, my UK counterpart, will be posting about the celebrations all week so be sure to check back for more OED fun. (Don’t forget to check out Sarah’s twitter updates about her trip!)

Sigh…what a day! So many things have happened I hardly know where to begin. I suppose I’ll start at the beginning. Sure you don’t want some popcorn before I start? Okay then.

I started my day off with a very peaceful and delicious breakfast in the hotel. The Old Parsonage is just that: the house where the parson lived. A big place for a parson (the head of specifically an Anglican church which for obvious reasons is right next door). When you walk in the gate there is a courtyard filled with tables where you can have tea on nice days and the walls are covered in a plant that is not ivy, but much as you would imagine buildings to be covered in England and just beginning to change color. You walk in a small wooden door and you are met with the smell of the fire burning cheerily surrounded by chairs and tables to sit and congregate. The bar is just past the fireplace and altogether it is warm and just a little dark as a very old (built in 1660) house should be. So just past the bar are a very few steps up to the room where I sat having a cup of coffee white (with warm milk that is) and toast (with marmalade that is literally the most perfect bittersweet marmalade all orange rind and jelly) and waited for my eggs and Cumberland sausage. Suffice it to say this would be the last moment of relative stillness all day.

Shortly after breakfast I met the group of journalists congregating near the fire (a very good place to congregate) and we all walked over to the Oxford University Press offices for the scheduled start of the events. We were missing one, she had just landed at Heathrow and was on her way by taxi. So after I walked the group over, with the help of Claire from the office who actually knows the way, I doubled back. Well, her taxi driver was lost and I nervously paced back and forth for nearly an hour, frequently checking the email updates from her about how the driver is saying they are “only a mile away”, before she finally arrives. The bellboy was incredibly helpful in renegotiating the fare (by the way his name is Hugh and his dad works for OUP, isn’t that a stroke of luck? So he’s my new friend). So we checked her bags and turned right around, back to the press. At this point I’ve missed most of the morning, the introductions and the tour of the OUP museum led by archivist, Martin Maw.

Lunch was at the Eagle and Child pub and I got fish and chips and a half pint of beer called “bare ass,” I kid you not. At lunch were three men, Edmund, Jeremy, and Peter, the authors of our book Ring of Words about Tolkien and the OED as well as Simon Winchester (who wrote The Professor and the Madman about the first editor of the OED, James Murray) and Ammon Shea who just wrote Reading The OED. Now the bird and baby is famous. It is where Tolkien and Lewis Carroll met with their group called The Inklings and drank and talked of literary things. It is sort of like Puck Fair but small and old and very…curious would be the right word. It really is like falling down Alice’s rabbit hole. Oxford is a place that has existed in my imagination from history and novels for ages now and it is so much like I imagined it (without McDonald’s and Gap) that it feels just a little disquieting.

This will have to be the first installment. It’s quarter past midnight and I’m hardly near the best part of the day…

ShareThis

By: Kirsty,

on 10/14/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reference,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

Dictionaries,

Online Resources,

oed,

oxford english dictionary,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

As Rebecca said yesterday, OUP UK is alive with the sound of the 80th anniversary celebrations for the Oxford English Dictionary. We’ve been having all manner of tours and workshops over the last couple of days with journalists and bloggers from both sides of the Atlantic coming along for the ride. I have been going along to some of the sessions and have quickly realised that even after working for Oxford University Press for more than three years there is still loads that I just didn’t know.

So, for my first post, I thought I’d share with you all some fascinating facts and figures about the Oxford English Dictionary. Did you know…

- -There are currently over 600,000 words in the OED

- -The OED costs over £4 million (or nearly $7 million) to run every year in editorial costs alone

- -… and it has never, ever made OUP any money!

- -As well as the addition of new words and senses to the Dictionary, the editors are also hard at work re-writing the historical information that is core to each OED entry for the first time

- -Work initially began on the OED in 1857, though the first edition didn’t appear in print until 1884, with ten volumes appearing between 1884 and 1928

- -The second edition appeared in print in 1989, and work is currently in progress on the third edition

- -The OED first went online in 2000

- -When starting to revise the OED for the third edition, the editorial team started at the letter M. They are currently on P,Q, and R.

- -They are also working on “big” words, which have long entries, such as ’sex’, ‘cool’, ‘big’, and ‘bad’.

- -Members of the public are welcome to write in if they have evidence of a word being used in print earlier than is currently recorded in the OED. This will be minutely checked and verified by the team of editors, and if found to be authentic, then the entry will be updated.

- -This recently happened with the word ‘microcomputer’. The OED team had traced it back to the mid-1960s, but just two weeks ago someone wrote in with evidence that it was used in an Isaac Asimov novel in the 50s. This is being verified now and if found to be correct, an updated entry will go online in December.

Fascinating, isn’t it? My favourite anecdote of the day came from Bernadette Paton, one of the OED’s Associate Editors. When revising the entry for the word ‘parachute’, she came across the following wonderful quotation from the Gloucester Journal in 1784:

“After having thrown a sheep six times from the top of a tower,..by the aid of a machine called a parachute, without the animal receiving any damage, he [Montgolfier, who invented the parachute] prevailed upon a man..to try the experiment, which was performed with the utmost safety.”

Good to know no sheep were harmed.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 9/19/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

golf,

Leisure,

info,

DNB,

Ryder cup,

Samuel Ryder,

ryder,

greats,

oxforddnb,

freeodnb,

58847,

golfers,

magazine,

Reference,

Current Events,

Oxford,

A-Featured,

oupblog,

Online Resources,

Add a tag

As much as we love spending all day reading the OUPBlog we recognize that there is other great content out there. For example the Ryder Cup Greats on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. From the 19th to 21st of September golfers from the United States and Europe battle it out for the Ryder Cup, the sport’s most prestigious team competition. The cup is named after Samuel Ryder, an English seed merchant and passionate amateur player, who funded an international match between British and American professionals in 1926 and sponsored a regular tournament from the following year.

To mark this year’s contest the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography has picked two teams of Ryder Cup greats active from the 1930s to the present day, and drawn from the Oxford DNB, American National Biography, and Who’s Who. Check it out!

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 7/30/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

reading,

Reference,

publishing,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Online Resources,

Oxford University Press,

oed,

online,

oup,

Casper Grathwohl,

Add a tag

Today we are excited to post an interview with Casper Grathwohl, Oxford’s Reference Publisher, in which he answers some frequently asked questions. Hopefully his answers with give you a glimpse inside the reference publishing world.

Casper Grathwohl is Vice President and Publisher of Reference at Oxford University Press. In his  10 years at the press, Casper has helped transform Oxford’s print dictionary and reference list into one of the leading online academic publishing programs in the world. Electronic initiatives within the Oxford program have included moving trusted copyrights online (Grove Dictionaries of Music and Art, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford Reference Online, and The Oxford English Dictionary) as well as building innovative new research tools such as Oxford Language Dictionaries Online and Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Prior to OUP, Casper worked for both Princeton University Press and Columbia University Press. He currently splits his time between New York and Oxford in England managing the two reference centers of the press.

10 years at the press, Casper has helped transform Oxford’s print dictionary and reference list into one of the leading online academic publishing programs in the world. Electronic initiatives within the Oxford program have included moving trusted copyrights online (Grove Dictionaries of Music and Art, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford Reference Online, and The Oxford English Dictionary) as well as building innovative new research tools such as Oxford Language Dictionaries Online and Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Prior to OUP, Casper worked for both Princeton University Press and Columbia University Press. He currently splits his time between New York and Oxford in England managing the two reference centers of the press.

1. What online resources do you daily and weekly?

I’m a big New York Times online fan. I made the switch from print to online a few years ago for my weekday news and it was a surprisingly easy transition. It’s funny—all these habitual activities we feel define us on a daily level (like reading the paper in the morning with a cup of coffee) are much more mutable than we think. I still like a lazy hour or two with the print paper on the weekends, but I can’t imagine reading an article that interests me and not being instantly able to surf for more on the topic, or follow the editorially-driven links provided.

Over the last couple of months I’ve really gotten into Street Easy. I’m in the process of buying an apartment in NY and one of my friends recommended I use it for information on comparable purchases in the building, sales history of the apartment and other stats. Most of the real estate listings in the city feed into the site, so it’s the one-stop shop that makes this kind of searching so much easier. And its functionality is highly intuitive—I’ve learned a lot about how to set up a really satisfying landing page from them.

These aggregator sites like Streeteasy are really interesting in that they serve the big and the small pretty equally. When the playing field gets leveled that way “large” loses one of its traditional advantages. I grew up in one of those small towns that had an empty downtown shopping area. All retail had moved out to the chain stores in malls and the local paper was filled with op-ed pieces regularly bemoaning the death of the American town and small businesses. And now look, twenty years later, organic butter infused with peaches from a small farm in Enigma, Georgia has a larger customer base online than it ever had before. (So large, in fact, that in 2004 it closed the “Berry Barn” located along Hwy 82 to focus on selling online.)

I love how online commerce has been such a shot in the arm to these types of mom-and-pop shops. As others have noted, the small independent stores that thrive are the ones that have a niche. They have a value proposition that we don’t associate (and will never want to) with big chains. Local peach butter from a Georgia farm? I’d take that over a new Parket margarine flavor any day! That’s their competitive edge, and with online commerce models anyone can find them. It’s this globalization of the local that I find so interesting. As I said, I’m not pointing out anything new here, I’m just having a great time watching it all happen.

What are you reading?

I just finished Joe O’Neill’s Netherland, which I loved. The plot and pacing are a little weak at times, but he’s such a lyrical writer that it’s easy to forgive. Every once in a while I’d come to a paragraph describing a subway station at rush hour or the way the sun hits Manhattan’s midtown and I’d swoon at how simply and perfectly he captured something I see everyday (and will always see a little differently from now on.)

What is your favorite reference work?

Such a hard question! I live knee-deep in the world of reference so it’s difficult to see it with any real perspective. I’m a big fan of reference-based online experiments, like the Encyclopedia of Life and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (which has proved to be a very successful, although not easily duplicated, experiment.) It’s sites like these that are the signposts to where scholarly communication is heading, and I find the energy these sites create really invigorating.

What do you think of Wikipedia?

I get this question a lot, and I think wikipedia is great. And I’m a little disappointed by all the complaints about how unreliable it is as a source. Of course it’s unreliable—quick, cheap information has never been anything but! In my circles I feel like there’s this myth that before user-generated web content everyone slavishly referred to trusted reference authorities for their quick information. If only. What did you do if you needed a quick answer to something in the pre-wikipedia dark ages? Nine out of ten times you’d call a friend or ask a colleague before pulling Britannica off your shelf. Was that more reliable? Absolutely not. But that’s OK, because you’d know not to site one of your friends in the bibliography of your research paper. I think if we start thinking of wikipedia as the equivalent of calling up one of your smart friends and getting a “good enough” answer (which is often all you’re looking for) then we’re on the road to responsibly understanding the awesome power of such user-generated resources.

As the web matures, it has come to reflect an image as complex and rich as culture itself. And therefore it should not surprise anyone that multiple layers of authority on the web are not just necessary, they are inevitable and already expanding. Wikipedia, Citizendium, Britannica, and Oxford Scholarship Online all complement each other as distinct, valuable places along the web knowledge chain.

And speaking of that web knowledge chain (not to go on a rant here)—we need to start making the distinction between information and knowledge. I would define knowledge most simply as “information in context.” Information is just a byte of something with a fact label attached. But what does that information mean? That’s knowledge.

For example, a 13-year-old obsessed with baseball statistics is a fine source for number of RBI’s or home runs Jackie Robinson had. Considering some of the boys I knew growing up, there might not be a more trusted source of such information. But you wouldn’t go to that 13-year-old and ask them to tell you about the significance of Jackie Robinson to the civil rights movement. That would be silly. Yet that’s what we do too often on the internet.

How did you get started in publishing?

Like most people I just fell into it. I liked books and was naïve enough to think that it qualified me for a job in publishing. I started out in publishing at the bookstore end of things: I worked in the buying office at Rizzoli in New York. I remember getting fed up because I was earning $16,000 a year (everyone my age trying to make it in NY was in the same boat, but I somehow failed to notice that) so I quit without another job. Bumming around New York for a summer after that was fun, but I was getting really tired of living on slices of pizza so I moved to Princeton to work as a typesetter at Princeton University Press. After a few years I became an editor and then moved back to New York to take a job editing the Columbia Gazetteer of the World. I love geography and had a great time with it. When that ended (I think it was 1997) I came to Oxford to work in the Children’s and Young Adult group and I’ve been here ever since. And I’ve got to say that I love OUP—the institution, the mission to disseminate knowledge, reinventing scholarly publishing online, all of it. And getting to be the keeper of the great Victorian publishing projects like the Oxford English Dictionary, Grove Music, and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is a privilege that regularly humbles me when I think about. How often do you get say something as lucky as that?

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 7/15/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

classical,

sibelius,

philharmonic,

tapiola—sibelius,

Music,

Biography,

Reference,

A-Featured,

Online Resources,

Finland,

concert,

Add a tag

Tonight I am planning on attending the New York Philharmonic’s performance in Central Park, presented by Didi and Oscar Schafer. I’m not a classical music buff but I have clearly heard of Tchaikovsky and Beethoven the first two composer’s on the bill. The third though, Sibelius gave me pause. So I turned to the new Oxford Music Online gateway which led me to The Oxford Companion to Music’s biography of Jean Sibelius, which I have excerpted below. Enjoy- and if you are in New York come listen tonight!

Sibelius, Jean (Julius Christian) [Johan Julius Christian Sibelius] (b Hämeenlinna, 8 Dec. 1865; d Järvenpää, 20 Sept. 1957).

Finnish composer. He was unquestionably the greatest composer Finland has ever produced and the most powerful symphonist to have emerged in Scandinavia. His father was a doctor in Hämeenlinna, a provincial garrison town in south-central Finland. Until he was about eight years old Sibelius spoke no Finnish. However, when he was 11 his mother enrolled him in the first grammar school in the country to use Finnish as the teaching language instead of Swedish and Latin. Contact with Finnish opened up to him the whole repertory of national mythology embodied in the Kalevala. His imagination was fired by this, as it was by the great Swedish lyric poets J. L. Runeberg and Viktor Rydberg and, above all, by the Finnish landscape with its forests and lakes.

In his youth Sibelius showed considerable aptitude on the violin and composed chamber music for his family and friends to play. There were few opportunities to hear orchestral music: even Helsinki did not have a permanent symphony orchestra until Robert Kajanus, later one of his staunchest champions, founded the City Orchestra in 1882. At first Sibelius studied law, but he soon abandoned it for music, becoming a pupil of Martin Wegelius. At about that time he decided to ‘internationalize’ his name (following the example of an uncle who had Gallicized his name, Johan, to Jean during his travels). It was not until he left Finland to study in Berlin and Vienna that he measured himself for the first time against an orchestral canvas.

It was in Vienna that the first ideas of the Kullervo symphony came to him, and it was this work, first performed in 1892, that put Sibelius on the musical map in his own country. The music that followed in its immediate wake is strongly national in feeling: the Karelia Suite, written for a pageant in Viipuri in 1893, has obvious patriotic overtones. So too has the music he wrote six years later for another pageant portraying the history of Finland which became a rallying-point for national sentiment at a time when Russia was tightening its grip on the country. One of its numbers, Finlandia, was to make him a household name; its importance for Finnish national self-awareness was immeasurable. From the time of Finlandia onwards, Sibelius was undoubtedly the best-known representative of his country, and many who would never otherwise have become aware of Finland’s national aspirations did so because of his music. (His birthday was a national event each year, and in 1935 his 70th culminated in a banquet at which were present not only all the past presidents of Finland but the prime ministers of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden.)

If the 1890s had seen the consolidation of Sibelius’s position as Finland’s leading composer, the next decade was to witness the growth of his international reputation. In 1898 he acquired a German publisher, Breitkopf & Härtel. (He later sold Valse triste to the firm on derisory terms, a decision he regretted to his dying day.) But his fame was not confined to Germany: Henry Wood included the King Christian II Suite at a Promenade Concert as early as 1901, and during the first years of the century his works were conducted by Hans Richter, Weingartner, Toscanini, and—in the case of the Violin Concerto—by no less a figure than his contemporary Richard Strauss. The Violin Concerto was very much a labour of love, as one would expect from a violinist manqué who had nursed youthful ambitions as a soloist.

Sibelius’s early compositions show the influence of the Viennese Classics, Grieg, and Tchaikovsky, and by the middle of the first decade of the 20th century, when Sibelius entered his 40s, his star had steadily risen. The Third Symphony (1907), however, brought a change in direction and showed Sibelius as out of step with the times. While others pursued more lavish orchestral means and more vivid colourings, his palette became more classical, more disciplined and economical. It was while he was in London working on his only mature string quartet, Voces intimae, that Sibelius first felt pains in his throat, and in 1909 he underwent specialist treatment in Helsinki and Berlin for suspected cancer. For a number of years he was forced to give up the wine and cigars he so enjoyed, and the bleak possibilities opened up by the illness served to contribute to the austerity, depth, and focus of such works as the Fourth Symphony (1911) and The Bard (1913). For tautness and concentration the Fourth Symphony surpasses all that had gone before. It baffled its first audiences and was declared ultra-modern; in Sweden it was actually hissed.

Although each of the symphonies shows a continuing search for new formal means, in none is that search more thorough or prolonged than in the Fifth (1915). Sibelius was a highly self-critical composer who subjected his music to the keenest scrutiny. In the early years of the 20th century En saga and the Violin Concerto were completely overhauled, and the Lemminkäinen Suite (1895) was revised twice, in 1897 and 1939. The Fifth Symphony gave him the most trouble of all: in its original form it was in four movements, and was first performed on his 50th birthday. It was turned into a three-movement work in the following year and entirely rewritten in 1919.

After World War I Sibelius’s music struck ever stronger resonances in England and the USA, and (perhaps because of that) fewer in Germany and the Latin countries. None of the symphonies is more radically different from the music of its time than the Sixth (1923), especially when compared with the music composed in the same year by Bartók, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Hindemith, and the members of Les Six. The one-movement Seventh Symphony (1924), which can be seen as the culmination of a search for organic unity, demonstrates the truth of the assertion that Sibelius never approached the symphonic problem in the same way. Tapiola (1926) crowns his creative achievement, evoking the awesome power of nature with terrifying grandeur. Of all his works this is the one that makes the most astonishingly original use of the orchestra.

Sibelius’s inner world was dominated by his love of the northern landscape, and of the rich repertory of myth embodied in the Kalevala. The classical severity and concentration of his later works was not in keeping with the spirit of the times, and after World War I he felt an increasing isolation. As he himself put it, ‘while others mix cocktails of various hues, I offer pure spring water’. For more than 30 years after the completion of his four last great works—the Sixth and Seventh Symphonies, the music for The Tempest, and Tapiola—Sibelius lived in retirement at Järvenpää, maintaining a virtually unbroken silence until his death in 1957. Although rumours of an Eighth Symphony persisted for many years, and its publication was promised after his death, nothing survives apart from the sketch of the first three bars. Near completion in 1933, it fell victim to his increasingly destructive self-criticism during World War II, probably in 1943.

Sibelius’s achievement in Finland is all the more remarkable in the absence of any vital indigenous musical tradition. Each of his symphonies is entirely fresh in its approach to structure, and it is impossible to foresee from the vantage point of any one the character of the next. His musical personality is the most powerful to have emerged in any of the Scandinavian countries: he is able to establish within a few seconds a sound world that is entirely his own. As in the music of Berlioz, his thematic inspiration and its harmonic clothing were conceived directly in terms of orchestral sound, the substance and the sonority being indivisible one from the other. Above all he possessed a flair for form rare in the 20th century; in him the capacity to allow his material to evolve organically (what one might call ‘continuous creation’, to adapt an image from astronomy) is so highly developed that it has few parallels. His mature symphonies show a continuing refinement of formal resource that (to quote the French critic Marc Vignal) makes him ‘the aristocrat of symphonists’. Vignal was referring to the sophistication of his symphonic means, but late Sibelius is also aristocratic in his unconcern with playing to the gallery and in his concentration on the musical and spiritual vision.

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 3/11/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Politics,

American History,

A-Featured,

Online Resources,

moss,

African American Studies,

mccarthy,

ufwa,

communist,

aanb,

african,

history,

biography,

oupblog,

american,

national,

1943,

Add a tag

After a decade of work, Oxford University Press and the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute published the African American National Biography(AANB). The AANB is the largest repository of black life stories ever assembled with more than 4,000 biographies. To celebrate this monumental achievement we have invited the contributors to this 8 volume set to share some of their knowledge with the OUPBlog. Over the next couple of months we will have the honor of sharing their thoughts, reflections and opinions with you.

Donald Ritchie, author of Reporting from Washington: The History of the Washington Press Corps, Our Constitution, and The Congress of the United States: A Student Companion, has been Associate Historian of the United States Senate for more than three decades. In the article below he looks at Annie Lee Moss.

A peculiar effort has been underway to rehabilitate Joe McCarthy as a Red-hunting investigator. Some commentators have declared the censured senator vindicated by the opening of Cold War archives that revealed the extent of Soviet espionage in the United States. A key figure in this debate is a witness whose brief appearance before McCarthy helped undo his public reputation: Annie Lee Moss. (more…)

Share This

I just want to say thanks to all of those who have responded -- in comments, in emails, on the phone, and in person -- to my rather sad end-of-the-year post, and who have said, in essence, Buck Up. Reading's not in decline... you've done so much already... a bookstore is worth waiting for... you'll do it someday... etc. You're all awesome.

Your enthusiasm and optimism, and your confidence in me, is like fuel to a fire. It's so good to have that encouragement -- better even than money. Aside from finally getting over a lingering stomachache I had over New Year's, your comments are the only thing to which I can attribute getting out of the blue funk I've been in. I'm excited again, and ready to roll up my sleeves.

I've just rediscovered an old favorite, Arts & Letters Daily, that great clearinghouse for the ideas being tossed about in the world, and I'm adding it to my Google homepage. Serendipitously enough, today there's a link to the British periodical New Statesman, and an article titled "Why life is good." I'd like to give it to you, as a gift, returning your own encouragement. It's only occasionally about the book stuff, but it is totally about the need for both optimism and working together. You can read the article for the supporting studies and statistics, but here are some excerpts for the jist:

People are not generally negative about their own lives... In contrast, we are unduly negative about the wider world. As a government adviser, I would bemoan what we in Whitehall called the perception gap. Time and again, opinion polls expose a dramatic disparity between what people say about their personal experiences and about the state of things in general.

While we apparently thrive in our own families of many shapes and forms, as social commentators we prefer to look back, misty-eyed, to the gendered certainties of our grandparents' generation.... What is true for families is true for neighbourhoods: we think ours is improving while community life is declining elsewhere. We tend to like the people we know from different ethnic backgrounds but are less sure about such people in general. We think our own prospects look OK but society is going to the dogs....

And yet. There is a different story to be told about our world. It is a story of unprecedented affluence in the developed world and fast-falling poverty levels in the developing world; of more people in more places enjoying more freedom than ever before.... When you read the next report bemoaning falling standards in our schools, remember the overwhelming evidence that average IQs have risen sharply over recent decades. If you think we have less power over our lives, think of the internet, of enhanced rights at work and in law, or remember how it was to be a woman or black or gay 30 years ago....

Self-actualisation is the peak of Maslow's hierarchy of needs. There is evidence that more of us are trying to climb that hierarchy. It is in the crowds at book festivals and art galleries, in ever more demanding consumerism with an emphasis on the personal, sensual and adventurous. We want to enjoy ourselves, to be appreciated and to feel we are growing from the experience....Today, there are signs of a yearning for new ways of working together. There is the growing interest in social and co-operative enterprise and the emergence of new forms of online collaboration... Despite the huge impersonal forces of the modern world, people are prepared not only to believe in a better future, but to work together to build it.

This is what we've got: in our indie bookstores, in our communities of readers. Ways of working together. The possibility of "self-actualization." An alternate story about the world. A good neighborhood. A better world.

(If you'd like more of that sort of thing, you might consider stopping by the bookstore to see Frances Moore Lappe on Monday night -- she's pretty compelling on that optimism and the working together stuff.)

Thanks, as always, for reading.

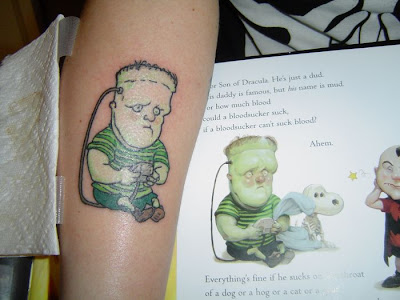

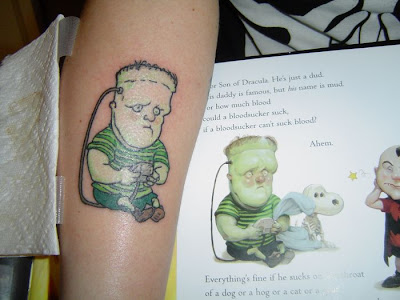

Members of the Navy may no longer be allowed to get tattoos, but that won't stop the rest of the world from this peculiar new sign of one's own innate awesomeness. Cooler than cartoon characters and more desirable than the names of loved ones, who can resist it? First came this bit on Lane Smith's blog . . .

. . and now Frankenstein Made a Sandwich has joined the ranks.

. . and now Frankenstein Made a Sandwich has joined the ranks.

Well played, Adam.

Hi,You've been tagged for blog tag! See my blog for the rules. http://thebumpyroadtopublishing.blogspot.com.Deb