new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Arts &, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 192

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Arts & in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

architecture,

Asia,

slideshow,

phillip,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

Images & Slideshows,

Arts & Leisure,

Indian history,

1600,

1300,

Deccan Plateau,

Phillip B. Wagoner,

Power Memory Architecture,

Power Memory Architecture: Contested Sites on India's Deccan Plateau 1300-1600,

Richard M. Eaton,

eaton,

wagoner,

plateau,

deccan,

Add a tag

By Richard M. Eaton and Phillip B Wagoner

Power and memory combined to produce the Deccan Plateau’s built landscape. Beyond the region’s capital cities, such as Bijapur, Vijayanagara, or Golconda, the culture of smaller, fortified strongholds both on the plains and in the hills provides a fascinating insight into its history. These smaller centers saw very high levels of conflict between 1300 and 1600, especially during the turbulent sixteenth century when gunpowder technology had become widespread in the region. Below is a selection of images of architecture and monuments, examined through a mix of methodologies (history, art history, and archaeology), taken from our new book Power, Memory, and Architecture: Contested Sites on India’s Deccan Plateau, 1300-1600.

-

Raichur. Kati Darwaza gateway (as reconstructed c. 1520)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-8.jpg

When an important fort changed hands in the early modern Deccan, victors often gave its gates “face-lifts” to publicize their possession of the site. When Krishna Raya of Vijayanagara seized Raichur from Bijapur, he erased features of this gate that were associated with Bijapur and stamped it with architectural markings of his own dynasty.

-

Yadgir Fort, Cannon no. 4 (late 1550s)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-7.jpg

In the mid-16th century the sultanate of Bijapur made notable advances in gunpowder technology, marking in some respects a local “Military Revolution”. This is seen in the crude adaptation of the idea of small swivel cannons to very large guns that were placed on high bastions and could be maneuvered both laterally and vertically.

-

Hyderabad: southern portal of the Char Kaman ensemble (1592)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-6.jpg

Though conventionally thought to have been patterned on “Islamic” models of urban design, Hyderabad was actually modeled on the Kakatiya capital of Warangal, indicating that dynasty’s lasting memory. Thus, four portals were positioned around the famous Charminar just as four toranas had been positioned around Warangal’s cultic center, the Svayambhu Shiva temple (see first image).

-

Warangal Fort: Panchaliraya temple, assembled by Shitab Khan (16th c.)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-5.jpg

In 1504 Shitab Khan, an upstart local chieftain, seized the city of Warangal from its Bahmani governor and at once associated himself with the memory of the illustrious Kakatiya dynasty, which had ruled from this city two centuries earlier. To this end, he made several architectural interventions, including assembling this temple from reused structural elements dating to Kakatiya rule.

-

Bijapur: Inner courtyard of citadel’s gateway

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-4.jpg

Like their Vijayanagara rivals to the south, the sultans of Bijapur also revered the memory of the imperial Chalukyas. This is seen in the twenty-four reused Chalukya columns that, in the early 16th century, they inserted in the citadel’s entrance courtyard, their capital’s most prominent site.

-

Vijayanagara: two-storeyed hall at the end of Virupaksha bazaar

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-3.jpg

To identify themselves with Chalukya glory, rulers of Vijayanagara in the 16th century inserted into this hall’s lower storey finely polished reused Chalukya columns, carved from blue-green schist. By contrast, the hall’s less visible upper storey exhibits columns in the style of Vijayanagara’s own period, crudely carved from nearby granite.

-

Kuruvatti. Bracket figure from the Malikarjuna temple, ca. 11th c.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-2.jpg

Just as the memory of Roman imperial splendor inspired Europeans for centuries after the collapse of Rome, the memory of the Deccan’s prestigious Chalukya dynasty (10th-12th c.), preserved by material remains such as this stunning sculpture, inspired actors four or five centuries later to identify their own regimes with Chalukya glory.

-

Warangal fort: Remains of the Tughluq congregational mosque

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Untitled-1.jpg

Architecture and power are interwoven in the remains of this mosque, built in the former capital of the Kakatiya dynasty. Foreground: rubble of the temple of the Kakatiyas’ state deity, Svayambhu Shiva, destroyed in the early 14th century by armies of the Delhi Sultanate. Background: one of the temple’s four majestic gateways (torana) that the conquerors preserved in order to frame the mosque.

Richard M. Eaton is Professor of History at the University of Arizona, Tucson. Phillip B. Wagoner is Professor of Art History at Wesleyan University. They are authors of Power, Memory, Architecture: Contested Sites on India’s Deccan Plateau, 1300-1600.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Contested sites on India’s Deccan Plateau appeared first on OUPblog.

By: LaurenH,

on 7/18/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Music,

excerpt,

obituary,

musical theater,

*Featured,

Theatre & Dance,

Arts & Leisure,

Eddie Shapiro,

Nothing Like a Dame,

Elaine Stritch,

Add a tag

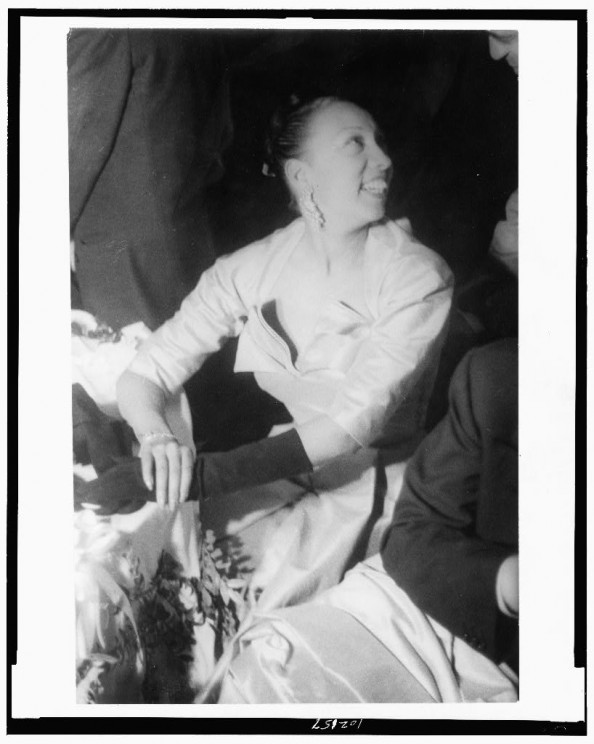

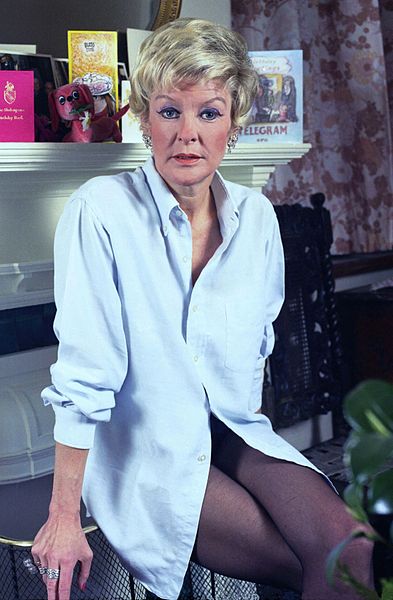

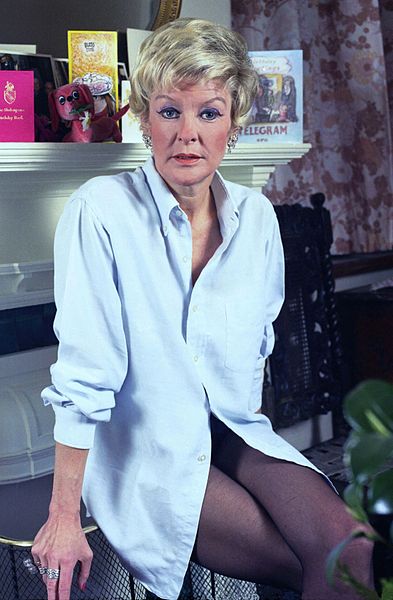

Oxford University Press is saddened to hear of the passing of Broadway legend Elaine Stritch. We’d like to present a brief extract from Eddie Shapiro’s interview with Elaine Stritch in November/December 2008 in Nothing Like a Dame that illustrates her tremendous life and vitality.

“What’s this all about, again?!” came Elaine Stritch’s unmistakable rattle of a voice, part Rosalind Russell, part dry martini, part cheese grater, on the other end of the phone. I was taken aback. After all, we had spoken the day before and the day before that. On the first call, she had told me that she was swamped but really wanted to get this interview out of the way. “Well,” I had offered, “there’s no great rush. I would rather you do this when you feel relaxed than when you are cramming it in.” “Don’t you worry about my disposition,” came the steely reply. “I’ll worry about my disposition.” She hated me, I thought, until the second call, during which she called me “dear” and apologized twice for her schedule. So now, on call number three, when it seemed we were back at square one, I didn’t know what to say. “Well, it’s the interview for my book, Nothing Like a Dame,” I explained. “You asked me to call today.” “And when did you want to do this,” came the deliberate reply. “Well, you asked me about today.” “Today? I can’t possibly do today.” “That’s fine. It’s just that when you called me on Friday, you said you wanted to get it done this weekend.” “I don’t recall saying that to anyone. Gee, Ed, I hate to leave you hanging like this. How about Thanksgiving?” “Thanksgiving Day?” “Yeah, before dinner. You could come for tea.” “That would be fine.” “But I tell you what, give me a call on Wednesday night after 11:00, just to confirm. And I promise I’ll remember.” And that is how I ended up having tea with irascible, cantankerous, outspoken, and utterly charming Elaine Stritch at The Carlyle Hotel on Thanksgiving Day.

Elaine Stritch was born outside of Detroit in 1925. She came to New York to study under Erwin Piscator at The New School, where her classmates included Marlon Brando and Bea Arthur (with whom she’d compete for a Tony Award sixty years later. And win.). She made her musical debut in Angel in the Wings, singing the absurd “Bongo, Bongo, Bongo (I Don’t Want to Leave the Congo)” before her long run as Ethel Merman’s understudy in Call Me Madam. Since Merman never missed a performance, Stritch never went on, and felt safe simultaneously taking a one-scene part in the hit 1952 revival of Pal Joey a block away. “I was close if they needed me,” she says, “which they never did.” When Call Me Madam went out on national tour, though, Stritch, all of twenty-five, was leading the company. Goldilocks followed, before Noel Coward wrote the role of Mimi Paragon in Sail Away just for Stritch. Mimi, like her inspiration, knew her way around an arched eyebrow and a sarcastic bon mot. Not surprisingly, Stritch was a sensation. It nonetheless took almost a decade for her next Broadway musical, but this one was legendary.

Elaine Stritch in her dressing room at the Savoy Theatre, London. 1973. Photo by Allan Warren, via WikiCommons.

As Joanne in Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s Company, Stritch bellowed the searing eleven o’clock number, “The Ladies Who Lunch.” To this day, it is considered one of the all-time greatest interpretations of any musical theater song. Hal Prince’s acclaimed 1994 revival of Show Boat was another triumph but the best was still to come. In 2001, under the direction of George C. Wolfe, Stritch premiered Elaine Stritch at Liberty, an autobiographical one-woman show in which Stritch gossiped, confessed, kvetched, cajoled, and reveled in a musical tour of her life and career. For At Liberty, she finally took home a Tony Award, before playing the show for years in New York, London, and on tour. In 2010, she successfully, if improbably, succeeded Angela Lansbury in A Little Night Music.

Of all the women in [Nothing Like a Dame], she was the only one I was scared to meet. The phone calls didn’t assuage my fears, nor did the Carlyle’s waiter who, upon hearing I was there to meet Stritch laughingly said, “Good luck!” But I needn’t have worried. Stritch isn’t mean, she’s just blunt to a degree that’s so unusual it’s occasionally unnerving. As Bebe Neuwirth says of her, “She doesn’t know how to lie, on or offstage.” And she doesn’t suffer fools well. But once she trusts, she’s delightful. And warm enough to have extended an invitation to Thanksgiving dinner.

…

In your show, Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, you said that you didn’t know why you wanted to be an actress. But you did choose to pursue acting over anything else. What gave you the instinct that you’d be any good?

I don’t think it’s an instinct, I don’t think that’s the right word. I don’t have an answer to that today.

Calling?

Those are all two-dollar words. I don’t believe in all of that, “calling” and “career.” I wasn’t thinking about . . . I think if I was really dead-honest, I was . . . everybody else was going away to college and I didn’t want to. I don’t know the reason why that was, either. I thought I’d rather learn by experience all of the subjects they were going to teach me in college. That’s a dumb statement. But I didn’t want to go to college. I wanted to be an actress but I still can’t tell you why. I think I’m . . . I don’t think I’m really a happy camper inside and I think it’s an escape for me. I’ve gotten to like myself a lot better as the years go by, but I’m still not hung up on myself.

You have actually said that it’s really hard for you to play yourself. During Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, you said that a vacation would be putting on a costume and playing someone else.

At the time I was doing Elaine Stritch: At Liberty I wasn’t thinking about philosophizing my position and what I would or wouldn’t like to do. This was a tremendously courageous thing for me to do, but it was good. Just like I read a good play—I read a Tennessee Williams play, an Edward Albee play—I read what I wrote and what John Lahr wrote and I liked it. I thought, “This is a good part for me.” That sounds like a joke but it was a good part for me to play. It was the first time I had an opportunity to put myself on the stage. Because I am a really true-blue actress. When I take on a part I play the part. Of course I bring Elaine Stritch to it, that’s why they hire me. But I am interpreting another, I am inside somebody else’s skin. So, you know, acting is . . . I don’t know what it is. I don’t think it’s given enough credit in the arts. I think it’s a real art form, acting. I don’t know. I don’t think a lot of people have the talent—my kind of talent—to be an actress. But there are a lot of good ones out there. I am always so thrilled when I go to the theater and see a performance. I just think that’s the best. There was a marvelous expression in the Times the other day in the review of Australia. They talked about all of the epic qualities of the movie but they said a very simple thing about Nicole Kidman, who I think is a very good actress. They said: “she gave a performance.” And I thought, “what a wonderful notice.” I hope she appreciates it.

I want to go back to your early days, you came to New York for whatever reason you . . .

For whatever reason. Look, it’s not as complicated as all that. I was not going steady with someone. My beau had already gone to New York to become an actor. He was a writer named James Lee. He wrote [the play] Career and he also wrote for television; he was one of the writers on Roots. So what was I gonna do? I didn’t want to go to college. I wasn’t in love. I mean, I loved Jimmy but I wasn’t interested in getting married. I wish it would stop there. I wanted to become an actress. Why? I don’t know. I think you deal with that better than I deal with it. I’d like to be able to answer it better. But I do think that I wasn’t too hung up on myself and I wanted to be everybody else I could think of.

The reason I used the word “instinct” is because I think sometimes people have a desire or gut feeling that isn’t calculated, but they know that something speaks to them.

Something stirring.

Yeah.

I see what you mean. Yes. And I also wanted out of Michigan. I love Michigan but I didn’t want to spend all my life there, I wanted to see the world. Another answer I’ve given to the question, “why did you want to become an actress” is that I wanted higher ceilings. It’s as good an answer as any. I once played a game at a party and we all had to give the best answer for “why did you become an actor.” Mine was, “to get a good table at 21.” Ho ho ho. I think “higher ceilings” would have won at that party but I hadn’t thought of that yet. [The actor] Marti Stevens gave the best answer ever. Actually, the question was, “why did you go on the stage” and Marti Stevens said, “to get out of the audience.” That’s a great answer.

Once you were in New York and at The New School, how did you get work and audition?

I was going to school.

Yes, but you were cast in Loco pretty quickly after school. Did that seem like a fluke to you or were your peers also getting work easily? Did it feel like a struggle?

I don’t know.

Did you have to work for money?

I waited tables at The New School, but I did it not because I needed the money; I did it for the experience.

The human experience?

Yeah.

Did it work?

Yeah. And I did it to show off to Marlon Brando.

Did that work?

Yeah. I was showing that I wasn’t just this rich girl from Michigan. I could be a waitress, too. You see there’s a little Joan Crawford/Mildred Pierce in all of us! It was all of those things. . . . I am very honest about things like that today. Then I wasn’t.

In what ways are you honest now that you were not then?

Well, I wish I could have laughed and told Marlon Brando that I was trying to influence him. But you don’t do that at seventeen. You wait ’til you’re in your eighties ’til you get that kind of honesty. I think I could do a lot of things today that I couldn’t do then as far as being straight- forward and on the level with people. I figured it out that none of us have anything to hide. There’s nothing about me that I couldn’t tell everybody in the world. There really isn’t. And that’s a good way to be. I love the expression “secrets are dangerous.” I really think they are. “Don’t tell anybody, but . . .” is the most boring line in the world. It really is. If you don’t want them to tell anybody, don’t tell them!

In saying secrets are dangerous, do you mean that the truth frees you?

Absolutely. And I think what has transpired without your knowing it is that you kind of, at last, dig yourself.

…

I need a Judy Garland story.

I’d have to look ’em up, Honey.

For people like me, it’s like sitting at my grandmother’s lap and listening to family legend.

I know, I know. Judy Garland, when she came to the opening night party of Sail Away, I made up my mind not to drink at all at that party. There were a lot of famous people there. Before I knew it I saw Judy leaving the Noel Coward suite, and she was going home. I thought, “My God, I haven’t talked to her, she hasn’t told me how she liked the show, and I really want to hear what she thought more than anyone.” They had those see-through elevators at the Savoy Hotel. I ran out to the hall and she was just on the elevator and it was starting to disappear. And before her head got out of view from me, she went, “Elaine, about your fucking timing . . . ” and then she disappeared. It was absolutely brilliant. She knew what she was doing! Her timing was divine! And music to my ears, of course.

Do you have any stories about working with George Abbott on Call Me Madam?

Oh, he was a marvelous director, a wonderful man and an extraordinary human being. I loved him. He did one great thing once with me. When I came down to get notes before opening night, I had a scotch and soda in a coffee mug. Of course I was making it very believable. ’Cause while he was giving the notes I was blowing on the coffee. I was blowing on the scotch. And all of sudden George Abbott said to me, “Can I have a taste of that Elaine? Is that coffee?” And my voice went up two octaves and I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Could I have a taste?” And I said, “Sure.” I’ll tell you what a great guy he was. He took the coffee mug from me and he blew on it and then he took a sip. And then he handed it back to me and said, “Man that’s good coffee.”

Do you have Richard Rodgers stories?

Oh, I loved him. But he didn’t like me. He was an alcoholic, you know, and alcoholics resent other alcoholics. He paid me a great compliment once, though. He said, “I would give her the lead in a show but I just don’t think she could handle it. Because when she does a number, it is so good that I never think she can do it again.” It’s a great compliment but it isn’t very conducive to working.

It is a back-handed compliment.

Well he was a back-handed kind of fellow. He is a hard person to talk about.

Did you think it was personal?

Oh no, he liked me very much. But I made him nervous because I drank. That would make any director or producer—but the funny thing with him was that he drank twice as much as I did.

Did he recognize that?

No, he didn’t at all.

Both Abbott and Rodgers knew that you were drinking . . .

It never bothered George Abbott because I didn’t drink too much. Well, I probably did drink too much, but I was never drunk on the stage in my life.

Was drinking in the theater more commonplace in general?

Absolutely. Everybody had booze in their dressing room. Nobody does anymore. In London, in the theater you have cocktail parties at intermission. It’s a big deal having a little sherry or a little of this or that. But too many people have abused the privilege in this country. All of our great actors were huge drinkers. Tallulah Bankhead, John Barrymore, Bela Lugosi. So many. Lots and lots of people.

The people you mention famously got seriously drunk. That was never you, though.

No, absolutely not. Maybe a couple of times my timing was off because I had three instead of two drinks, but nothing to write home about.

…

Do you read reviews?

Oh yes, I can’t wait. Terrified to read them and thrilled to death when they are good. I haven’t gotten a lot of bad reviews; I’ve gotten a few in my life but nothing that upset me terribly.

There are a lot of actors who . . .

I can’t believe that they don’t read their reviews.

Do you go to the theater today?

Yeah, I go. But I am not going to see The Little Mermaid if that’s what you mean. I like Jane Krakowski, I think she’s good. And I like Kristin Chenoweth. I’m getting very excited about the opening of Pal Joey because my good friend Stockard Channing is in it. The theater is not what it was. It’s the fabulous invalid. It’s having a tough time because of the economy but it will come back. I worry about Maxwell [her nephew, a twenty-nine-year-old actor who just moved to New York]. Nobody who comes here to get into the theater can get an agent. It takes years. You have to go on those cattle calls. This is a tough racket. It really is a tough racket.

…

If performing hadn’t worked out for you, do you have any notion of what you might have been doing?

Supposition is really boring but I’ll give it a shot: Stay home!!

Is there anyone you’ve never worked with who you wish you had?

If I am supposed to, it’ll happen. I reiterate: supposition to me is a long yawn.

I think the word is “boring.”

[Laughs] OK, whatever you think is fair.

Excerpted from Nothing Like a Dame: Conversations with the Great Women of Musical Theater by Eddie Shapiro. Shapiro is a freelance writer and theater journalist whose work has appeared in Out Magazine, Instinct, and Backstage West. He is the author of Queens in the Kingdom: The Ultimate Gay and Lesbian Guide to the Disney Theme Parks.

The post In remembrance of Elaine Stritch appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/10/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

composer,

sheet music,

*Featured,

bangor,

Arts & Leisure,

rhiannon,

Bangor University,

Helios,

Melos,

music composition,

North Wales Music Festival,

Rhiannon Mathias,

William Mathias,

mathias,

whitland,

Add a tag

By Rhiannon Mathias

My father was a man of exceptional energy. Warm and generous in character, he lived several different kinds of musical lives. First and foremost, of course, as a composer, but also conductor, pianist, public figure, Professor of Music at Bangor University (1970-88) and Artistic Director of the North Wales Music Festival (1972-92). All these different strands amounted to a phenomenal workload, and took up a great deal of time, but he felt that he couldn’t write music 24 hours a day, and that he could give something meaningful to society and move it on. It did mean that he had to be extremely well organized, but I think that he found that all the different aspects of his life helped him to produce the music he wanted to write in the end. Much of his music was composed in our family home in the town of Menai Bridge on the beautiful island of Anglesey, and our house was also ‘mission control’ when he was planning his Music Festival.

His working day usually started at 9 a.m., and he often drove me to school in the mornings in his ‘English red’ (actually, bright orange) Mercedes on his way to the University. I think he quite enjoyed his time at the University. There was not as much paperwork as there is these days, and he enjoyed the lecturing and was very popular with his students. He was affectionately known as ‘Prof’, and my mother, who was head of singing at the Department, was ‘Mrs. M’. His office took up the entire top floor of the music building. I recall a grand piano (model D, of course), bookshelves weighed down with the history of Western music, and an enormous desk bearing scores and papers.

There is a story about him which dates from his time when he was a young lecturer at Bangor in the 1960s. He would begin his lecture, and after about ten minutes would reach for his pipe and light a match while still enthusing about his subject. The students would watch the match burn down, whereupon he would put it out and place it in his jacket pocket. Without breaking his speech, he would reach for another match, light it, and the process would repeat until, by the end of the lecture, he was left with one unlit pipe and a pocket of spent matches. Later, when he became a Professor, he rarely made negative comments about concerts given at the University, but if he was not, how shall I say, fully musically engaged, he would take his glasses off and wipe them with his tie. We all came to realise that this was the ultimate critical comment!

When he got home from the University, my mother would have a delicious meal ready for him. His day was far from over, however. Unless my parents were hosting a dinner party – my mother is an excellent cook – he would go to his studio after supper and compose until the early hours of the morning. These regular, ‘golden’ hours, enabled him to compose nearly 200 published works, including three symphonies, several concertos, chamber music, a great deal of choral music, and a full-scale opera, The Servants. Such a routine seems extraordinary, but it is important to understand that music was an ever-present force for my father. I was aware from a very early age that the creative process was something always present for him — even when he was doing something else — and that it was a force which he could turn in any desired direction or channel at a given time. Hence his ability to compose a wide variety of orchestral, choral, instrumental or chamber music, as well as music for the church and for young people.

I could always tell when a piece was gestating in his mind because he would become intensely thoughtful and preoccupied. When the time was right, he would roughly sketch the piece, trying out a few ideas on one of the two pianos in his studio, and then attend to the detailed work of producing his meticulously tidy manuscripts — always in black ink (this was in the days before Sibelius). The majority of his works were written to commission, and from as far back as I can remember, he usually had to plan two, often three years in advance in order to meet the demand of commissions he wanted to fulfil. He told me that sometimes, after finishing his composition in the early hours, he used to pop into my bedroom when I was very young and find me standing up in my cot, waiting for him to come and say goodnight.

His enormous work commitments meant that we, as a family, rarely went on holiday during the summer. There were, however, regular trips to Whitland in South Wales, my father’s home town, to visit my grandmother Marian, and I recall a wonderful holiday in Greece – impressions of which partly became the inspiration for his Melos for flute, harp, percussion and strings (1977) and Helios for orchestra (1977). In 1982, we went to America where my father embarked on an immensely successful tour of the East coast involving lectures, performances, and workshops in Boston, New York, Athens in Georgia, and San Antonio in Texas. The connection with the States was a lasting one and, after my father’s retirement from Bangor University in 1988, it became usual for him to visit America twice, often three times a year.

At the beginning of 1992, my father was commissioned to write a symphony (his fourth) by the Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra. Sadly, the new symphony was not to come to fruition — he passed away in July 1992 — but the true, creative artist has an uncanny ability to transcend mortality. He would have been 80 in November, and it is wonderful that his anniversary is being celebrated this year by a series of concerts, festivals, and new publications. His vibrant character – full of vitality, optimism, and joy – very much lives on in his music.

Rhiannon Mathias is a musicologist, broadcaster, and flautist. She is the author of a book about the music of Elisabeth Lutyens, Elizabeth Maconchy, and Grace Williams (Ashgate 2012) and lectures on Twentieth-Century Women Composers at Bangor University. She is also a Trustee of the William Mathias Music Centre in north Wales.

William Mathias was born in Whitland, Dyfed. He studied at the University College of Wales, and subsequently at the Royal Academy of Music. From 1970-1988 he was Head of the Music Department at the University College of North Wales, Bangor. Mathias musical language embraced both instrumental and vocal forms with equal success, and he addressed a large and varied audience both in Britain and abroad. He was also known as a conductor and pianist, and gave or directed many premières of his own works. He was made CBE in the 1985 New Year’s Honours. In 1992, the year of his death, Nimbus Records embarked upon a series of recordings of his major works.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the United States by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post William Mathias (1934-92) by his daughter, Rhiannon appeared first on OUPblog.

By: VictoriaD,

on 7/8/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

yeats,

picasso,

patent,

james joyce,

gmo,

oxford music online,

ezra pound,

OMO,

sylvia beach,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

vincent,

Online products,

Grove Music Online,

Meghann Wilhoite,

megwilhoite,

meghann,

wilhoite,

ballet mecanique,

erik satie,

george antheil,

to a nightengale,

antheil,

glandular,

r8vn_65ybd4,

Add a tag

By Meghann Wilhoite

American composer and self-proclaimed “bad boy of music” George Antheil was born today 114 years ago in Trenton, New Jersey. His most well-known piece is Ballet mècanique, which was premiered in Paris in 1926; like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, from which Antheil seems to have derived quite a bit of inspiration, the premiere resulted in audience outrage and a riot in the streets. The piece is scored for pianos and a number of percussion instruments, including airplane propellers.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Though he died at the age of 58, polymath Antheil managed to accomplish quite a bit in his relatively short life both in and outside the field of music. Here are some highlights:

- His name appears alongside the actress Hedy Lamarr’s on a patent, granted in 1942, for an early type of frequency hopping device, their invention for disrupting the intended course of radio-controlled German torpedoes.

- In 1937 he published a text on endocrinology called Every Man His Own Detective: A Study of Glandular Criminology. The book includes chapters on “How to read your newspaper” and “The glandular rogue’s gallery”.

- His music was championed by the likes of James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Sylvia Beach, W.B. Yeats, Erik Satie, and Pablo Picasso.

- Under the pseudonym Stacey Bishop, he wrote Death in the Dark, a detective novel edited by T.S. Eliot, the hero of which is based on Pound.

- After spending the majority of the 1920s and 30s in Europe, he settled in Hollywood and wrote dozens of film, television and radio scores, for directors such as Cecil B. DeMille and Fritz Lang (and with such titillating titles as “Zombies of Mora Tau” and “Panther Girl of the Kongo”).

- Last, but not least, here is Vincent Price narrating Antheil’s “To a Nightingale” with the composer himself on piano: George Antheil – Two Odes of John Keats – To A Nightingale: Vincent Price, narrator; George Antheil, piano

Meghann Wilhoite is an Associate Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post George Antheil, the bad boy of early twentieth century music appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/3/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

boucher,

Arts & Leisure,

Online products,

West African music,

>William Boucher,

bannjo,

Joel Walker Sweeney,

Sarah Rahman,

Sir Hans Sloane,

832330,

banjos,

rahman,

precursors,

plucked,

attachment_70385,

Music,

banjo,

ORO,

Oxford Reference,

*Featured,

African American music,

Add a tag

By Sarah Rahman

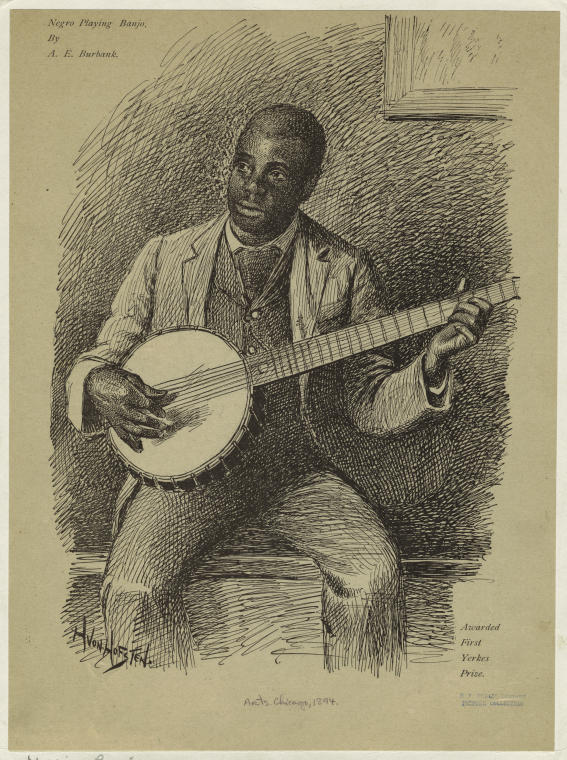

The four-, five-, six- stringed instrument that we call a “banjo” today has a fascinating history tracing back to as early as the 1600s, while precursors to the banjo appeared in West Africa long before it was in use in America. Explore these fun facts about the banjo through a journey back in time.

- The banjo was in use among West African slaves since as early as the 17th century.

- Recent research in West African music shows more than 60 plucked lute instruments, all of which, to a degree, show some resemblance to the banjo, and so are likely precursors to the banjo.

- The earliest evidence of plucked lutes comes from Mesopotamia around 6000 years ago.

- The first definitive description of an early banjo is from a 1687 journal entry by Sir Hans Sloane, an English physician visiting Jamaica, who called this Afro-Caribbean instrument a “strum strump”.

- The banjo had been referred to in 19 different spellings, from “banza” to “bonjoe” by the early 19th century.

- The earliest reference to the banjo in North America appeared in John Peter Zenger’s The New-York Weekly Journal in 1736.

- William Boucher (1822-1899) was the earliest commercial manufacturer of banjos. The Smithsonian Institution has three of his banjos from the years 1845-7. Boucher won several medals for his violins, drums, and banjos in the 1850s.

- Joel Walker Sweeney (1810-1860) was the first professional banjoist to learn directly from African Americans, and the first clearly documented white banjo player.

- After the 1850s, the banjo was increasingly used in the United States and England as a genteel parlor instrument for popular music performances.

- The “Jazz Age” created a new society craze for the four-string version of the banjo. Around the 1940s, the four-string banjo was being replaced by the guitar.

Sarah Rahman is a digital product marketing intern at Oxford University Press. She is currently a rising junior pursuing a degree in English literature at Hamilton College.

Oxford Reference is the home of reference publishing at Oxford. With over 16,000 photographs, maps, tables, diagrams and a quick and speedy search, Oxford Reference saves you time while enhancing and complementing your work.

Subscribe to OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 10 fun facts about the banjo appeared first on OUPblog.

By: VictoriaD,

on 7/1/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

interview,

Music,

q&a,

gmo,

oxford music online,

OMO,

anastasia,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music,

Online products,

Grove Music Online,

Meghann Wilhoite,

megwilhoite,

meghann,

wilhoite,

Life at Oxford,

baroque music,

Grove editorial,

pipe organ,

fagerheim,

jarle,

tsioulcas,

medievalpoc,

Add a tag

Since joining the Grove Music editorial team, Meghann Wilhoite has been a consistent contributor to the OUPblog. Over the years she has shared her knowledge and insights on topics ranging from football and opera to Monteverdi and Bob Dylan, so we thought it was about time to get to know her a bit better.

Do you play any musical instruments? Which ones?

In order of capability, I play the pipe organ, piano, synths, and guitar. I also sing a bit, but I gave up on my dream of being an opera singer long ago!

Organ Console, Holy Trinity, Buffalo, NY. Photo by Jarle Fagerheim. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Do you specialize in any particular area or genre of music?

As an organist, I mostly play Baroque music (I <3 Bach 5eva), though I recently commissioned an excellent piece from contemporary composer Matthew Hough, which we’ll get to recording as soon as we have the funding. As a pianist, I play lots of different stuff from Classical era onwards. As a synth player and guitarist I play indie rock, mostly stuff I’ve written or stuff I’ve collaborated on.

What artist do you have on repeat at the moment?

My current lifestyle sort of dictates what I listen to right now: I’m either on the subway or blocking out ambient sounds in the office (nothin’ but love for my fellow cube dwellers), which means it’s difficult to listen to stuff where there’s an extreme difference between the loudest and the softest sound. Thus, artists like Interpol, Cocteau Twins (Elizabeth Fraser swoon), and Grimes dominate my playlist; if I had more time in quieter spaces I would also be listening to more avant-garde stuff as well.

What was the last concert/gig you went to?

The last concert I went to was part of the series I help run called Music at First; we were presenting the music of Jerome Kitzke, and it was pretty wild.

How do you listen to most of the music you listen to? On your phone/mp3 player/computer/radio/car radio/CDs?

Phone on the subways, computer (Pandora or Spotify) at work.

Do you find that listening to music helps you concentrate while you work, or do you prefer silence?

Music definitely helps me concentrate while I work, with the exception of creative writing.

Has there been any recent music research or scholarship on a topic that has caught your eye or that you’ve found particularly innovative?

Actually, my most recent scholarship binge has been on historiography, specifically the white-washing of European history (there’s a great Tumblr called MedievalPOC that focuses on the white-washing of European art). I would love to do more research on people of color with regards to the Western music canon (you know, those same hundred or so pieces by the same twenty or so composers that every music history textbook teaches you about).

Who are a few of your favorite music critics / writers?

Anastasia Tsioulcas (NPR, et al.) and Steve Smith (Boston Globe) are two critics/writers whose work I admire. They give an honest take on the music they’re reviewing without getting polemical, and they both promote gender parity within the field.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Associate Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Getting to know Grove Music Associate Editor Meghann Wilhoite appeared first on OUPblog.

By: VictoriaD,

on 6/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

TV & Film,

film scores,

Arts & Leisure,

Grove Music,

Online products,

Grove Music Online,

oxford music,

Scott Huntington,

favor movie,

joe kraemer,

movie scoring,

scores,

kraemer,

for favor,

Music,

huntington,

oxford music online,

OMO,

independent films,

temp,

Film Music,

Add a tag

Ever wondered what goes into scoring film music? Is the music written during filming? Or is it all added after the film is finished? Regular OUPblog contributor Scott Huntington recently spoke with film composer Joe Kraemer about his compositional process, providing an inside look at what it’s like to score music for an independent film.

Scott Huntington: What’s your process of creation like?

Joe Kraemer: Ideally, I see the movie without any temp score, but these days, that is rare. [Director] Chris McQuarrie doesn’t like temp scores, so the two films I’ve done with him (The Way of the Gun, Jack Reacher) we skipped the temp process and I was able to work with a clean slate, so to speak.

I look at a scene, and based either on the cutting, the dialogue, or the rhythm of the scene, I find the spot where I believe music should come in. Then I roll on down until I think music should go out. I don’t use any hard and fast rules. A lot of it is based on feel.

Once I’ve decided where the music will start, I try and find the right tempo for the music, fast or slow. Next I consider the color of the music, light or dark, major or minor, brassy or strings, and so on. I continue on this path of binary decision-making until I reach a solution. If that solution doesn’t work, I work my way back and try something else, such as a faster tempo, a different color or a different instrumentation. Sometimes, I make decisions that don’t really have a logical explanation, but they just feel right. I like to refer to the scene in “Star Wars” where Ben Kenobi is cut down by Darth Vader, and John Williams scores the sequence with a sweeping version of Princess Leia’s Theme, because that theme has great sweep and scope, and Ben’s theme was more somber. His decision seems nonsensical from a logical point of view, but it’s right-on from an emotional point of view.

Scott Huntington: Have you seen changes in technology impact the way you score movies?

Joe Kraemer: Well, the AVID editing system has opened up the audio side of things for film editors completely. As a result, films are built with really well-edited temp scores right from the get-go. In the old days, a Moviola or a flat-bed had one or two tracks of sound, so the temp score was something that was laid in very bluntly, just to create a feeling or atmosphere, without it needing to be a definitive presentation. Now, the ability to edit the temp score to match the picture in minute detail has resulted in everyone accepting it as the baseline standard for the film. The editor cuts the scene to the temp, the director looks at the cut with the temp, right away the temp is now the point of comparison for the rest of the process. Even if the composer never sees the temp, he or she is competing with it. The composer’s music is evaluated as much for whether it matches the temp as whether it works for the scene in the first place.

What you end up with is the picture-editor making a lot of the decisions about the music before the composer even has a shot at bringing something of himself (or herself) to the table. That isn’t inherently bad, picture editors usually have great taste in music, but as a composer it can feel restrictive. Also, you end up with a lot of films sounding the same, because all the editors fall in love with the same piece of music at the same time. Case in point, for about 10 years after “American Beauty” came out, all I heard in temp scores was Tom Newman’s score for that movie. There are only so many ways one can reinvent piano chords over sustained string beds.

As far as the composing work itself, for me the computer-based paradigm has been a life-saver. From adjusting tempos to catch cuts, to mixing electronic sounds with acoustic sounds, computer-based composing has made it possible for me to make a living as a composer, even when films have had skimpy music budgets, because I can do all of the work myself. I don’t use an assistant; I don’t have a team of ghost-writers. I put all my time and effort into making the score as good as possible myself, within the means at my disposal. Technology makes that possible.

Scott Huntington: Describe the process of writing the music for Favor.

Scott Huntington: Describe the process of writing the music for Favor.

Joe Kraemer: The process starts as soon as the movie is over the first time I see it. I immediately begin thinking about different aspects of the score: what will the instrumentation be? What will the mood be? The tone?

Next comes a period of living with the film. If possible, I get a copy and watch it on repeat for a day or two in my studio while I update my software and do busy work, etc. Once I’ve seen the film a dozen times or so, it’s time to start composing in earnest.

At some point between seeing Favor the first time and getting my own copy to work from, I was swimming in the pool and doodling melodies in my head and I came up with a nice little tune I though would sound pretty on the cello. I made a mental note of it and filed it away in my noggin for some later use.

Some time later, as I sat down to begin writing the cues for Favor, I remembered that melody and found that on a piano, it had a cold sound that contrasted nicely with the beauty of the tune. This seemed to be appropriate for my needs, as I was writing a theme for a character that, rarely seen, hangs over the film like a specter. This contrast of cold and beauty felt right.

Next, I decided I needed some kind of musical “sound effect” to help with certain story elements I wanted the score to reinforce. This was the impetus behind what [director] Paul [Osborne] and I began to call the “Abby Stab”. It’s a sound of a hammer hitting an anvil that has been tweaked with a bunch of plugins. I used it whenever I wanted to audience to think of Abby, to be reminded of her fate, to keep her present in a scene even when she wasn’t there.

After that, it was mostly a task of assembling the music to match what Paul laid out in his temp score. Paul cuts his own films and I know from working with him the past that he is very particular about the way his temp interacts with the editing of the film, so I worked very hard to stay faithful to the way he would crescendo to a cut. That being said, there were major sequences where Paul had no temp score, but I added music because I thought it was an effective spot.

Scott Huntington is a percussionist specializing in marimba. He’s also a writer, reporter and blogger. He lives in Pennsylvania with his wife and son and does Internet marketing for WebpageFX in Harrisburg. Scott strives to play music whenever and wherever possible. Read his previous blog posts and follow him on Twitter at @SMHuntington.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Scoring independent film music appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/24/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Arts & Leisure,

Musical Quarterly,

Alma Schindler,

Gustav Mahler,

Justine Mahler,

Mahleriana,

Morten Solvik,

Natalie Bauer-Lechner,

Stephen E. Hefling,

hefling,

lechner,

solvik,

morten,

Music,

Journals,

bauer,

mahler,

Add a tag

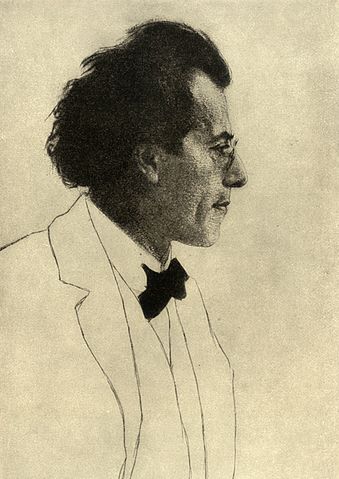

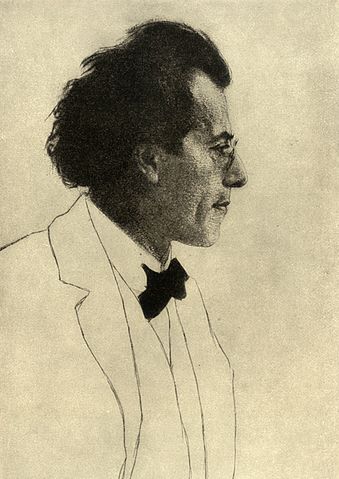

For many years, scholarship on composer Gustav Mahler’s life and work has relied heavily on Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s diary. However, a recently discovered letter, introduced, translated, and annotated by Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling, and published for the first time in the journal The Musical Quarterly, sheds new light on the private life of the great composer. New revelations about various relationships, including Bauer-Lechner’s romantic involvement with the composer, sketch out his personal character and provide a more nuanced portrait. We spoke with Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling about the impact on Mahler scholarship.

Gustav Mahler, photo of the etching by Emil Orlik (1903), in the Groves Dictionary and New Outlook (1907). Collections Walter Anton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Natalie Bauer-Lechner is the primary witness to roughly 10 years of Gustav Mahler’s life; biographers and historians have continually relied on her accounts to shed light on Mahler’s works and thoughts, especially during the 1890s. In this letter, three main topics are discussed in ways never before documented in Mahler studies: (1) Mahler’s various romantic involvements before his marriage to Alma Schindler in 1902; (2) the role of Justine Mahler, the composer’s sister, in his personal interactions with these women; and (3) Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s two brief periods of sexual relations with Mahler, at the beginning and at the end of her 12-year relationship.

The implications go beyond the merely biographical, as it reveals the author in a liaison – long-suspected by some scholars – with the object of her recollections. How, then, do we evaluate her writings? How trustworthy is the information they claim to provide? Since Bauer-Lechner has heretofore been considered absolutely reliable, the ramifications of a revision of this stance could have far-reaching consequences.

How was this letter discovered, and what kept it from being published for so long?

The letter had been in private hands until it appeared in the shop of a Viennese rare books dealer and was sold to the Music Collection of the Austrian National Library in the fall of 2012. The authors first became aware of the document in the spring of 2012 when it became known that the owner had attempted (unsuccessfully) to sell the letter through the Dorotheum Auction House in Vienna in May 2011. How the letter ended up in this person’s possession has not (yet) been determined. Its authenticity is firmly established.

Does the publication of this letter vindicate, or just as equally cast into doubt, any previously published writing on Mahler?

This depends on one’s perspective. Some will conclude that Bauer-Lechner’s romantic interludes with the composer precluded any objectivity in her recollections of him and that her accounts must therefore be called into question. Others will point out that Bauer-Lechner’s diaries include much factual information corroborated by many other sources and that there is little reason to doubt the authenticity of her “Mahleriana” as a whole; indeed, her degree of objectivity is all the more remarkable given her emotional involvement. For discretion’s sake she declined to reveal the extent of her intimacy with Mahler in the pages of her diary that she intended to publish. But that Bauer-Lechner manipulated or fabricated information seems a contrived conclusion; that she was unable to avoid a certain partiality or missed certain details should hardly strike us as surprising.

Does the letter pose any new questions for future Mahler scholars?

The most imposing and immediate challenge that emerges from this letter is the need to collate all extant materials that Natalie Bauer-Lechner produced in her lifetime in connection with Gustav Mahler. The present authors are in the midst of precisely this project in an attempt to present the most complete account possible. This will facilitate a better informed evaluation of the value of her narrative, the extent of its objectivity, its shortcomings, and no doubt more information regarding Mahler. In particular, the content of the letter clearly indicates the need to reevaluate Alma Mahler’s claim that at the time of their marriage, Mahler “was extremely puritanical” and “had lived the life of an ascetic.”

Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling are the authors of “Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women: A Newly Discovered Document” in the Musical Quarterly. Morten Solvik is the Center Director of the International Education of Students (IES) Abroad Vienna where he also teaches music history. Stephen E. Hefling is a Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve University.

The Musical Quarterly, founded in 1915 by Oscar Sonneck, has long been cited as the premier scholarly musical journal in the United States. Over the years it has published the writings of many important composers and musicologists, including Aaron Copland, Arnold Schoenberg, Marc Blitzstein, Henry Cowell, and Camille Saint-Saens. The journal focuses on the merging areas in scholarship where much of the challenging new work in the study of music is being produced.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post New questions about Gustav Mahler appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Taylor Coe,

on 6/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

playlist,

Summertime,

Louis Armstrong,

summer songs,

Dizzy Gillespie,

Ella Fitzgerald,

Gorillaz,

Lovin' Spoonful,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Audio & Podcasts,

Arts & Leisure,

April Come She Will,

Kenny Chesney,

Rockin' Sidney,

Rudi Carrell,

summer playlist,

Sunny Afternoon,

Add a tag

Compiled by Taylor Coe

Now that summer is finally here – dog-eared paperbacks and sunglasses dusted off and put to good use – it’s also time to figure out what we should be listening to as we loll about in the sun. While the media seem more concerned with which current pop hit will become the unofficial “Song of the Summer” (Pharrell’s “Happy”? Iggy Azalea’s “Fancy”?), here at OUP, we have instead zeroed in on songs from summers past. Ranging all the way back to 1957 (for Ella and Louis’s take on Gershwin’s classic “Summertime”) and all the way over to Germany (for Dutch television host Rudi Carrell’s fanciful ode to sommer on the North Sea), we have pulled together a diverse and inspired set of tunes to take along to the beach, or the Pizza Hut, or the New York City streets, or wherever you should find yourself this summer!

“Summertime” – Kenny Chesney

I’ve been to his amazing concerts at MetLife Stadium for the past three years and this song has been my anthem ever since. “And it’s two bare feet on the dashboard / Young love and an old Ford / Cheap shades and a tattoo / And a Yoo-Hoo bottle on the floorboard.”

— Leslie Schaffer, Special Accounts Sales Rep

The Lovin’ Spoonful, best known for their 1966 summer smash “Summer in the City,” make two appearances on our Summer Songs playlist. Public domain, via Wikimedia

“Summer in the City” – The Lovin’ Spoonful

Now that I live and work in New York City this song speaks to me. While the summer days are brutal and exhausting, the nights are wonderful. During the day we are tortured by sweltering sidewalks, oven-like subway stations, and loud construction noises, but at night the city cools off and comes alive again. There’s nothing I love more than drinks on a rooftop in the summer. In fact, I think that’s what I’ll do tonight.

— Christie Loew, Assistant Manager Accounts and Merchandising

“Summer of Panic” – Hanoi Janes

“Summer Bonfire” – Great Lakes Myth Society

“Summer Wine” – Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood

“Vacation” – the Go-Gos

The song that’s been my summer anthem since it came out in 2010 is Hanoi Janes’s “Summer of Panic.” The song’s frenetic pace, distorted and muted vocals, and a mix of old school chords with what Pitchfork reviewer Jayson Greene called “swarms of wiggling B-movie lasers” make for a psychotic surf music vibe that can’t be beat. It perfectly captures my love-hate relationship with summer, where I feel such pressure to have fun while it lasts, that it becomes panic-inducing. Its companion piece, Great Lakes Myth Society’s “Summer Bonfire,” might sound less fraught with anxiety, but only because some of the verses trail off, leaving you to supply the missing rhyme that, for instance, turns “electric” into “electric chair.” But for those times when I am able to relax, Nancy Sinatra and Lee Hazlewood’s “Summer Wine” is a must listen. Hazlewood plays the role of a cowboy whom Sinatra seduces, drugs, and eventually robs. Nevertheless, the languid tempo, their sultry vocal blend and the brass chorus somehow makes this odd song sound like a hot summer night. I am now considering that as my three favorite summer songs involve nervous breakdowns, capital punishment, and committing felonies, I might need a long summer vacation. There’s always the Go-Gos.

— Anna-Lise Santella, Editor, Grove Music/Oxford Music Online and Music Reference

“Jalapeno Lena” – Rockin’ Sidney

The Summer of ’88 was the first year I didn’t return home from college but stayed in Plattsburgh to live and work the summer away at two part-time jobs. In the morning I prepped at Pizza Hut, “makin’ it great.” That summer must have been around the time Dirty Dancing came out because the jukebox played “Time of My Life” by Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes ad nauseum. To break up the nauseum, my fellow prepper, Snooze Warner, and I would play any random, little-known songs we could find in that jukebox. Then one day we stumbled upon “Jalapeno Lena” by Rockin’ Sidney and we thought it was brilliant. Whenever someone played “Time of My Life,” we ran out and played “Jalapeno Lena.” It has a killer zydeco beat that helped us beat the heat of the summer of ’88, a hot summer in Plattsburgh, NY only made hotter by “Jalapeno Lena” and the ovens of Pizza Hut.

— Purdy, Director of Publicity

“See No Evil” – Television

Summer vacations back from college were all about driving up and down the coast of Maine in my dad’s old beat-up convertible, blasting Marquee Moon and Fun House and Unknown Pleasures and Blank Generation on burned CDs. The disc cartridge was in the trunk, so if you wanted to put in something different, you had to pull over and get out. Whenever I hear those records, that’s where I go.

— Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist

“Everybody Loves the Sunshine” – Roy Ayers

“I Get Lifted” – George McCrae

Breezy and light, “Everybody Loves the Sunshine” gets to the core of a lazy day in the sweltering sun. As for “I Get Lifted,” if I had a drop top in the city, this is what I would blast driving in July.

— Stuart Roberts, Editorial Assistant

“Feel Good Inc.” – Gorillaz

One of the hit singles from the cartoon band Gorillaz, this was song of the summer in 2005! According to Wikipedia it is the only song by any one of Damon Albarn’s several bands (including Blur and The Good, the Bad, and the Queen) to hit the Billboard Top 40.

— Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Publicity Manager

Click here to view the embedded video.

“Wann wird’s mal wieder richtig Sommer” – Rudi Carrell

This German Schlager favorite is sung to the tune of “City of New Orleans” and became summer song of the year in 1975. And this video version from Carrell’s TV show isn’t to missed. The lyrics describe a singer nostalgic for heat waves that he used to experience on the North Sea. (!)

— Norm Hirschy, Editor, Music Books

“Coconut Grove” – The Lovin’ Spoonful

“Summertime” – Jason Rebello

“Long Long Summer” – Dizzy Gillespie

There are a few Lovin’ Spoonful songs I could have chosen – “Summer in the City” being an obvious one – but it is “Coconut Grove” that reminds me most of sitting on a beach at sunset. As for George Gershwin’s “Summertime”, there are so many versions that many of them are classics themselves. But when I first heard Jason Rebello’s arrangement from his 1994 album Make it Real, it felt so new and exciting. And then Dizzy Gillespie’s sound is sunshine itself! I could have picked any number of his songs for this playlist, but this is the track that I play when the sun comes out.

— Miriam Higgins, Music Hire Librarian

“Sweet Amarillo” – Old Crow Medicine Show

Not to say that I’m at all over the rollicking Dylan-Old Crow collaboration that is “Wagon Wheel,” this next 40-years-in-the-making tune is equally excellent. According to OCMS frontman Ketch Secor, Dylan’s management company sent the band a cassette with the song fragment along with a set of instructions for how Dylan wanted the song to be completed, and – voilà! – Ketch and company make Americana magic once again!

— Taylor Coe, Marketing Associate, Academic/Trade Books

“Here’s to the Night” – Eve 6

When I was in high school, I spent every summer up in the Santa Cruz Mountains, working at a small summer camp called Forest Footsteps. That camp will always hold a special place in my heart and to this day, I still consider my fellow staff members and the campers as my extended family. On the last night of each week, we had a camp-wide “Boogie” with all the kids where we danced to an assortment of classic oldies and fun summer tunes. The final song was always “Here’s to the Night” by Eve 6 and as soon as the first few notes played, everyone would circle up in the middle of the dance floor and put their arms around one another, singing and swaying together as a group. Even the most introverted kids would find their way into the circle, embraced by their cabin mates. It was a really beautiful way to wrap up the week and that song still brings a tear to my eye, in the best possible way.

— Carrie Napolitano, Marketing Assistant, Academic/Trade Books

“Steal My Sunshine” – Len

Nothing says driving around town with the top down like this song.

— Sarah Hansen, Publicity Assistant

“Sunny Afternoon” – The Kinks

“Lazing on a sunny afternoon . . .” Need I say more?

— Louise Bowler, Senior Marketing Executive, Journals

“Postcards from Italy” – Beirut

My favorite summer song is “Postcards from Italy” by Beirut. It has such a romantic, old-timey feel to it. Even its title oozes summer – when I hear “postcards” and “Italy” I think of sunshine, the Mediterranean sea, and, of course, gelato! It also helps that the opening bars are played on a ukulele – the quintessential summer instrument! Bellisima.

— Mary Teresa Madders, Marketing Assistant, Journals

“Endless Summer” – The Jezabels

“Miami” – Will Smith

“April Come She Will” – Simon and Garfunkel

The summer-ness of The Jezabels’ “Endless Summer” comes down to this: You’re sixteen and the summer holidays are never going to end. You can practically feel the sweat run down your back as you laze on the beach with your holiday romance. And of course there’s “Miami,” the quintessential summer tune by the great Will Smith. Bringing rap to the masses, this accessible classic will have even your nan nodding her head. Or maybe she would prefer the short but sweet Simon and Garfunkel tune “April Come She Will,” which, with a hint of that classic Watership Down soundtrack, offers a bittersweet metaphor of birth, life, and death. Perfect for a pensive summer afternoon.

— Simon Turley, Marketing Assistant, Journals

“Summertime” – Ella Fitzgerald & Louis Armstrong

This song lulls like a summer afternoon, rocking on the back porch watching the day go slowly, gently by.

— Anna Hernandez-French, Assistant Editor, Journals

Taylor Coe is a Marketing Associate at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A 2014 summer songs playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

We asked our composers a series of questions based around their musical likes and dislikes, influences, challenges, and various other things on the theme of music and their careers. Each month we will bring you answers from an OUP composer, giving you an insight into their music and personalities. Today, we share our interview with composer and cellist Aaron Minsky. Visit his YouTube channel for an insight into the man and his music.

We asked our composers a series of questions based around their musical likes and dislikes, influences, challenges, and various other things on the theme of music and their careers. Each month we will bring you answers from an OUP composer, giving you an insight into their music and personalities. Today, we share our interview with composer and cellist Aaron Minsky. Visit his YouTube channel for an insight into the man and his music.

Which of your pieces are you most proud of and holds the most significance for you?

I am most proud of my concerto, The Conqueror. It utilizes the experience of 30 years of cello performing and composing plus a lifetime of study of the great orchestral works. Written during the immensely threatening Hurricane Sandy, it is imbued with drama and power. The piece is loosely based on the life of Genghis Khan and contains Mongolian-type melodies synthesized with rock cello concepts. I am thrilled with the prospect of seeing it performed in major concert halls. I gave the world premiere this spring in New York City with the Staten Island Philharmonic.

Which composer were you most influenced by and which of their pieces has had the most impact on you?

My solo cello works reveal my debt to J. S. Bach. I considered his Cello Suites the ‘Bible’ of cello composing and loved how he utilized the range of the instrument to create self-standing contrapuntal gems. As great as his suites are, I wanted to create new suites with modern musical influences to carry on the tradition. I knew I could never match the loftiness of Bach, but I felt I could fill a gap in the repertoire with new techniques and styles, and do it with an emphasis on joy!

Can you describe the first piece of music you ever wrote?

Most of my early pieces were songs, but my very first composition was in the style of Mozart. I was aware of the great composers even before I became influenced by the music of my generation.

Have the challenges you face as a composer changed over the course of your career?

The biggest challenge is staying relevant. It’s hard to believe that my first publication with OUP dates back to the 1980s. The Cold War was ending, the dollar was strong, and the Soviet Union was in shambles. The popularity of the United States was at a high and American culture was embraced around the world. In this climate, Ten American Cello Etudes was a perfect fit. Then globalization took hold, multiculturalism became the byword, and Ten International Cello Encores reflected this change. Most recently, Pop Goes the Cello proposes a new popular style of cello playing beyond the confines of any particular region.

If you could have been present at the premiere of any one work (other than your own) which would it be?

The most inspiring premiere that ever took place had to have been Beethoven‘s Ninth. A previous OUPblog describes it this way: ‘Back to the audience, facing the orchestra, the composer steadily marked the tempo with his hands. He was not conducting, though — he was deaf. Thus it was that, when the orchestra and chorus finished, he could not hear the applause and cheers of the Vienna audience. When a musician turned him around so he could see the joy on listeners’ faces, Ludwig van Beethoven bowed in gratitude — and wept.’

What is the last piece of music you listened to?

Whatever was on the radio. I tend to surf around and listen to a wide range of music — from the classics to rock to jazz to world music.

What might you have been if you weren’t a composer?

I might have been a rock star. My early influences were bands that combined classical music with rock such as the Beatles. I was also influenced by improvising bands, like the Grateful Dead. While still in high school I became a professional guitarist. Feeling that Hendrix, Clapton, and a few others had done just about all one could with a guitar I saw the cello as open territory. I was ready to plant my flag when, due to changing musical currents, the curtain fell on experimental rock ending my dream. I remember around that time staring at a picture of Fernando Sor (the great guitar etude writer) and thinking, I may never become a rock star but I bet I could preserve my melodies in cello etudes. Thus the composer seed was planted.

What piece of music have you discovered lately?

After my trip to England last year I was inspired to dig into its great symphonic heritage. I listened to the complete symphonies of Vaughan Williams among others. I have particularly enjoyed Vaughan Williams’s London Symphony (in which I hear shades of one of my heroes, George Gershwin).

Is there an instrument you wish you had learned to play and do you have a favourite work for that instrument?

I wish I had studied keyboards earlier. That would have been helpful for my composing. There are so many great pieces. If I had to pick a favorite I’d say Brahms‘ Second Piano Concerto. But I love many instruments including the french horn, the English horn, the bass clarinet, even the contra-bassoon — all of which are featured in my concerto!

Is there a piece of music you wish you had written?

Of course I wish I had written the Dvořák Cello Concerto. But I am glad to have composed the Minsky and am honored to be following in his footsteps.

What would be your desert island play list? (three pieces)

I would do what I usually do when I travel — listen to the music from where I am. Since this island would be surrounded by the ocean I would listen to the music of the sea! First on my list would be La Mer by Debussy, which captures the bluster of the glorious, churning sea. Then I’d pick A Sea Symphony of Vaughan Williams for its depth and powerful exploration of emotions connected with the sea. Finally, I would pick Jimi Hendrix’s 1983 A Merman I Should Turn to Be for its imaginative depiction of life under the sea.

How has your music changed throughout your career?

This is best answered by taking a trip to my website. I have audio clips of myself as young as 13 years old jamming out on guitar in every rock style I could muster. Some of the songs I wrote at age 14 have held up pretty well. You can hear in the tapes I made from age 16, the onset of classical influences. You can also hear the birth of the ‘celtar’. In the tapes from my college years you hear the influence of jazz, world music, and improvisation. We also hear the early days of my career as a classical cellist. From there my move back into rock can be heard with clips of the Von Cello Band. The website pretty much ends with Von Cello but will soon be updated to show how I have moved back toward classical, especially in my compositions … which brings us back to the first question about which piece I am most proud. I hope my concerto will be just the first step in the next chapter of my life: Aaron Minsky — orchestral composer.

American cellist, Aaron Minsky’s compositions are standard repertoire, his music appearing in the curriculums of the ABRSM, the American String Teachers’ Association, and the Australian Music Examinations Board. Aaron has given masterclasses and performances in the United States, England and Ireland, and has an Australian tour planned for later this summer. Also known as Von Cello, Aaron has appeared on radio and television and has performed with a wide range of artists from David Bowie and Tony Bennett to Mstislav Rostropovitch. Aaron’s ‘celtar’ style (which combines cello and guitar technique) has entered both the popular and classical musical worlds. He had a broad musical education, studying with Harvey Shapiro and Channing Robbins of Juilliard, Jonathan Miller of the Boston Symphony, George Saslow, Einar Holm, and David Wells of Manhattan School of Music where he obtained a Master of Music degree. More at Aaron Minsky’s website.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the United States by Peters Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of Aaron Minsky.

The post Composer and cellist Aaron Minsky in 12 questions appeared first on OUPblog.

By: DanP,

on 6/14/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Is the Planet Full?,

‘chemistry,

book festivals,

hay festival,

chris evans,

Life at Oxford,

After Thermopylae,

Ian Goldin,

hay festival 2014,

500 words competition,

stephen fry,

atkins,

peter atkins,

goldin,

farquhar,

Kate Farquhar thomson,

peter cartledge,

what is chemistry?,

cartledge,

thomson,

chemistry,

festival,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Add a tag

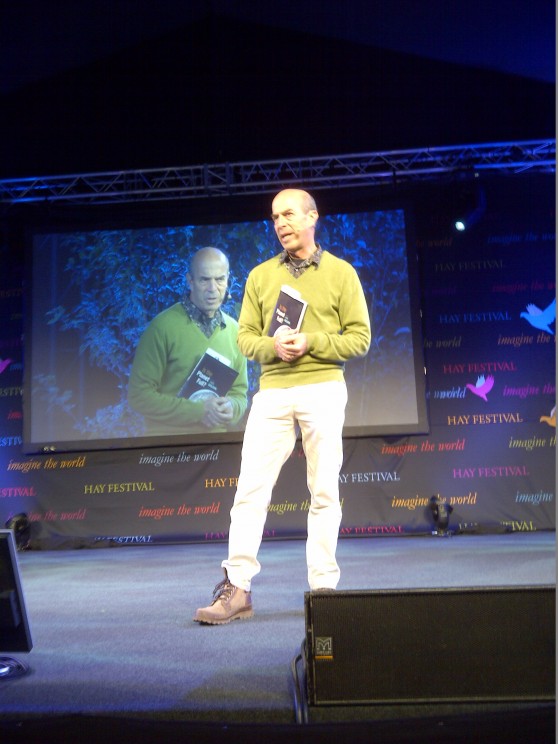

By Kate Farquhar-Thomson

It was down to the trustworthy sat nav that I arrived safe and sound at Hay Festival this year; torrential downpours meant that navigating was tougher than usual and being told where to go, and when, was more than helpful.

Despite the wet and muddy conditions that met me at Hay, and stayed with me throughout the week, the enthusiasm of the crowd never dwindled. Nothing, it seems, keeps a book lover away from their passion to hear, meet, and have their book signed by their favourite author. But let’s not ignore the fact that festival-goers at Hay not only support their favourite authors, they also relish hearing and discovering new ones.

My working holiday centres on our very own creators of text, our very own exponents of knowledge, our very own Oxford authors! Here I will endeavour to distil just some of the events I was privileged to attend in the call of duty!

Peter Atkins was an Oxford Professor of Chemistry and fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford until his retirement in 2007 – many of us, including myself, studied his excellent text-books at ‘A’ level and at university. What Peter Atkins does so well is make science accessible for everyone and none less so than an attentive Hay audience. Peter puts chemistry right at the heart of science. ‘Chemistry has rendered a service to civilization’ Atkins says ‘it contributes to the cultural infrastructure of the world’. And thereon he took us through just nine things we needed to know to ‘get’ chemistry.

Ian Goldin’s event on Is The Planet Full? addressed global issues that are affecting, and will affect, our planet. So, is the planet full? Well, the Telegraph tent for his talk certainly was! Goldin, whose lime green sweater brought a welcome brightness to the stage, is Professor of Globalisation and Development and Director of the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford. His words brought clarity and insight: “politics shapes the answer to this question,” said Goldin.

Hay mixes the young with the old and academics with us mere mortals, and what we publishers call the ‘trade’ authors with the more ‘academic’ types. This was demonstrated aptly by Paul Cartledge who right from the start referenced an earlier talk he attended by James Holland. Cartledge is A.G. Leventis Professor of Greek Culture at University of Cambridge and James (who is an ex-colleague and friend) is a member of the British Commission for Military History and the Guild of Battlefield Guides but a non-academic. The joy of Hay is that it brings everyone together. Paul Cartledge was speaking about After Thermopylae, a mere 2,500 years ago, but rather a more tricky period to illustrate through props and pictures which Holland so aptly used in his presentation.

OUP had 15 authors at The Hay Festival but the Hay Festival also had other visitors such as Chris Evans whose show was broadcast live from the festival as it was the 500 Words competition announcement and I was lucky enough to be there.

So what does Hay mean to me? It’s a unique opportunity to get up close and personal with heroes in literature and culture, as well as academia. It’s a week of friends, colleagues, and drinking champagne with Stephen Fry whilst discussing tennis with John Bercow – and wearing wellies every day!

Kate Farquhar-Thomson is Head of Publicity at OUP in Oxford.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Stephen Fry, Ian Goldin, and 500 Words competition at the Hay Festival. Photos by Kate Farquhar-Thomson: do not reproduce without permission.

The post Post-Hay Festival blues appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Taylor Coe,

on 6/12/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Can't Stop the Music,

Dangerous Rhythm,

film musicals,

Why Movie Musicals Matter,

richard barrios,

barrios,

backstories,

Books,

Music,

movie,