new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Mark, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 11 of 11

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Mark in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 7/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

Mark,

baron,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

concise,

spelling bee,

gleanings,

*Featured,

spelling reform,

slough,

myrk,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Baron, mark, and concise.

I am always glad to hear from our readers. This time I noted with pleasure that both comments on baron (see them posted where they belong) were not new to me. I followed all the references in Franz Settegast’s later article (they are not yet to be found in such abundance in my bibliography of English etymology) and those in later sources and dictionaries, and, quite naturally, the quotation from Isidore and the formula in which baron means “husband” figure prominently in every serious work on the subject. No one objected to the hypothesis I attempted to revive. Regrettably, Romance etymologists hardly ever read this blog. In any case, I have not heard their opinion about bigot, beggar, bugger, and now baron. On the other hand, when I say something suspicious or wrong, such statements arouse immediate protest, so perhaps my voice is not lost in the wilderness.

Thus, in one of the letters sent to Oxford University Press I was told that my criticism of the phrase short and concise “is not well taken,” because legal English does make use of this tautological binomial, along with many more like it, in which two synonyms—one English and one French—coexist and reinforce each other. What our correspondent said is, no doubt, correct, and I am aware of numerous Middle English legal compounds of the love-amour type. However, I am afraid that some people who have as little knowledge of legalese as I do misuse concise and have a notion that this adjective is a synonym of precise. Perhaps someone can give us more information on this point. I also want to thank our correspondent who took issue with my statement on the pronunciation of shire: my rule was too rigid.

As for mark, our old correspondent Nikita (he never gives his last name) is certainly right. Ukraine (that is, Ukraina) means “borderland.” In the past, the word was not a place name, and other borderlands were also called this. Equally relevant are the examples Mr. Cowan cited. I don’t know whether Tolkien punned on myrk-, but Old Icelandic myrk- does mean murk ~ murky, as in Myrk-við “Dark Forest” (so a kind of Schwarzwald) and Myrk-á “Dark River.”

Spelling and general intercourse.

I suspect that Mr. Bett (see his comments on the previous gleanings) is an advocate of an all-or-nothing reform. I’d be happy to see English spelling revolutionized, and my suggestion (step by step) is based on expedience (politics) rather than any scholarly considerations. When people speak of phonetic spelling, they usually mean phonemic spelling, so this is not an issue. But I would like to remind everyone that the English Spelling Society was formed in 1908. And what progress has it made in 116 years? Compare the two texts given below.

To begin with, I’ll quote a few passages from Professor Gilbert Murray’s article published in The Spectator 157, 1936, pp. 983-984. At that time, he was the President of the Simplified Spelling Society.

“There are two plain reasons for the reform of English spelling. In education the work of learning to read and write his own tongue is said to cost the English child [I apologize for Murray’s possessive pronoun] a year longer than, for example, the Italian child, and certainly tends to confuse his mind. For purposes of commerce and general intercourse, where the world badly needs a universal auxiliary language and English is already beginning in many parts of the world to serve this purpose, the enormous difficulty and irrationality of English spelling is holding the process back.…”

He continued:

“Now nearly all languages have a periodic ‘spring cleaning’ of their orthography. English had a tremendous ‘spring cleaning’ between the twelfth and the fourteenth century.… It is practically Dryden’s spelling that we now use, but few can doubt that the time for another ‘spring cleaning’ is fully arrived… It must not be supposed that the reformers want an exact phonetic alphabet…. What we need is merely a standard spelling for a standard language…. The ‘spring cleaning’ which my society asks for is, I think, quite certain to come; though the longer it is delayed the more revolutionary is will be. It may come, as Lord Bryce, when President of the British Academy, desired, by means of a Royal Commission or a special committee of the Academy. It may, on the other hand, come through the overpowering need of nations in the Far East, and perhaps in the North of Europe, to have an auxiliary language, easy to learn, widely spoken, commercially convenient, and with a great literature behind it, in a form intelligible to write and to speak.”

All this could be written today, even though with a few additions and corrections. English is no longer beginning to serve the purpose of an international language; it has played this role since World War II. We no longer believe that the desired “cleaning” is sure to come: we can only hope for the best.

Let us now listen to Mr. Stephen Linstead, the present Chair of the English Spelling Society, who said to The Daily Telegraph on 23 May 2014 the following: “The spelling of roughly 35 percent of the commonest English words is, to a degree, irregular or ambiguous; meaning that the learner has to memorise these words.” A need to memorize irregularity, he explains, “costs children precious learning time, and us—as a nation—money…. A study carried out in 2001 revealed that English speaking children can take over two years longer to learn basic words compared with children in other countries where the spelling system is more regular.”

We can see that our educational system is making great strides: what used to take one year now takes two. Mr. Linstead says other things worth hearing of which I’ll single out the proposal. It concerns the formation of an international English Spelling Congress “made up of English speakers from across the world who are open to the possibility of improving English spelling and who would like to contribute to the difficulty of mastering our spelling system.” As I understand it, the reformers plan to pay special attention to organizational matters, rather than arguing about the details of English spelling. This looks like a rational attitude. The public is not interested in the reform. Nor did it show any enthusiasm for it in 1936. There were two letters to the editor in response to Professor Gilbert’s article, but both came from the members of the Society, that is, from the “choir.” If the Congress materializes, it should include a lot of very influential people (what about Lord Bryce’s idea?). Otherwise, we will keep talking for another one hundred and six years without any results.

Busy as a bee.

The public, as I said above, does not care about the reform, but it is greedy, covets monetary prizes, and sends children to a torture known as spelling bee. The hive originated in 1925. Here is a case of a bright thirteen year old boy. He speaks English (and to some extent two other languages, one of them learned at home) and is an avid reader. He made it to the semifinals but misspelled ananke (a useful word that reminds even the gods that doom is unavoidable—just what a young boy should keep in mind). I don’t know what he did wrong. Probably he assumed that the word was Latin and spelled it with a c, but alas and alack, it is Greek. For eight weeks a coach (another young student) used to work with the boy three times a week. What a waste! The boy said: “I was really nervous, because you really don’t know what word you were going to get. I wanted to make it farther. [However,] I was really pleased with how I did and how I placed.” I am afraid he will grow up knowing several hundred words he will never see in books and using really three times in two lines. Remembering the spelling of ananke will be the only reward for his efforts.

A snake in the slough of despond. Image credit: A Cantil (Agkistrodon bilineatus) with a shed skin nearby at Little Ray’s Reptile Zoo. Photo by Jonathan Crowe. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via mcwetboy Flickr.

I think society (society at large, not the Spelling Society) should do what administrators, masters of a meaningless jargon, call sorting out priorities, stop abusing children, forget the fate of the gods, and concentrate on the misery of the mortals who try to make sense of bough, cough, dough, rough, through, and the horrors of the word slough.

To be continued next week.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for June 2014, part one appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/25/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

Mark,

etymology,

march,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

marchioness,

marquis,

marquise,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The names of titles have curious sources and often become international words. The history of some of them graces student textbooks. Marshal, for instance, is an English borrowing from French, though it came to French from Germanic, where it meant “mare servant” (skalkaz “servant, slave”). Constable meant “the count of the stable.” One of the highest officers in Norwegian courts was skutil-sveinn “cup-servant” (the hyphen in foreign compounds is here given for convenience). As everybody understands, only reliable people could be responsible for the king’s stable, cup, bed, or bottle (from bottle we have butler, not necessarily royal). Later, such words became titles divorced from their original meanings, while other people—if I am allowed to pursue the equine metaphor—continued to curry favor with the high and mighty. Herzog means approximately the same as duke, that is, “leader (of the army).” It may have been an independent Germanic coinage, not a “calque” (translation loan) of some Greek noun.

Titles tend to wander (compare marshal, above) and sometimes get entangled in a way baffling to a modern etymologist. There was an old German word gravo (with long a, which means with the vowel of Modern Engl. spa), the name of various royal administrators. Its continuation, Modern German Graf, sounds familiar to English speakers from landgrave (German Landgraf) and the name Palsgrave (from count palatine; palatine “pertaining to the palace”). Although the origin of gravo is not entirely clear, it need not delay us in this story. Alongside gravo, Old Engl. (ge)refa existed. In Anglo-Saxon times, it was the name of a high official having local jurisdiction. It has survived as reeve and can, with some effort, be recognized in the disguised compound sheriff, that is, shire reeve. (Many people mispronounce the word shire: it rhymes with hire, but as part of place names, for Instance, Cheshire or Yorkshire, it is a homophone of sheer.) In late Old Icelandic we find the title greifi, corresponding to German Graf. It could have been a borrowing of Old Engl. gerefa or, more likely, of some German reflex (continuation) of Old High German gravo. The uncertainty stems from a chance similarity of two unrelated nouns.

The most famous of all marquises: Madame (Marquise) de Pompadour.

Titles may reflect jurisdiction over some territory, as is, from a historical point of view, the case with sheriff. This brings us to the origin of marquis, originally the ruler of a so-called march, or frontier district. Once again the word was taken over by English from French, but its homeland is Germanic. A synonym of marquis is margrave, or to use its obsolete form, markgrave (German Markgraf). Mar(k)grave reminds us of landgrave (German Landgraf). The central element in the story of marquis is mark, the source of French marque and a most important term in the legal system of the speakers of ancient Germanic. It meant “sign,” “boundary,” and, by extension, “district.”

Mark is English. When after a long stay on Romance soil it returned to Middle English, it had the form march. Mark and march, in so far as they mean “boundary,” are synonyms and etymological doublets. The verb march “to constitute a border” has limited currency, but it is a living word in some situations, especially when used about countries and estates. This is exactly where I, at that time an undergraduate, first encountered it. A character in Jane Austen says: “Our estates march.” I needed a dictionary to understand the sentence. Either because, in North America, there have never been estates of quite the British type or because fewer and fewer young people understand rare words, when I cite this usage in my courses on the history of English and German, it is always new to the students and causes surprise. In England it would probably, and in Scotland certainly, have been different.

The Old English for mark was mearc, and it appeared as the first element of numerous components. Historically, march is most familiar with reference to the boundaries between England and Scotland and England and Wales. Old Engl. Merce or Mierce were “people of the march,” or “borderers”; hence Mercia, the Medieval Latin name of their borderland. Its inhabitants were Mercians, and their dialect is called Mercian. Those who lived outside the “mark” were foreigners, aliens, as follows from the alja-markir on a rune stone (alja is related to Engl. else). The use of the word mark in place names and the names of the people who live in such places is nothing out of the ordinary. The county of Mark (German Die Mark) in Westphalia offers a typical example; compare the Mark of Brandenburg. And there were Marcomanni, an old Germanic tribe, obviously, still other inhabitants of a borderland.

Mark “sign” and mark “border” are two senses of the same word. The Century Dictionary says: “The sense ‘boundary’ is older as recorded, though the sense ‘sign’ seems logically prevalent.” There has been some discussion about the order of those senses, but the opinion, just quoted, seems to carry more conviction, though Hjalmar Falk and Alf Torp, the authors of the great and excellent etymological dictionary of Norwegian, thought differently. Mark “sign” occurs also in the compound landmark.

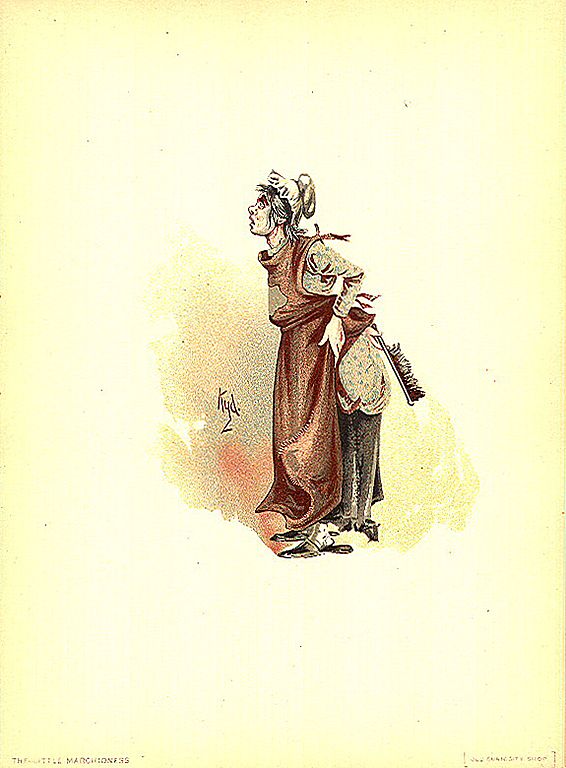

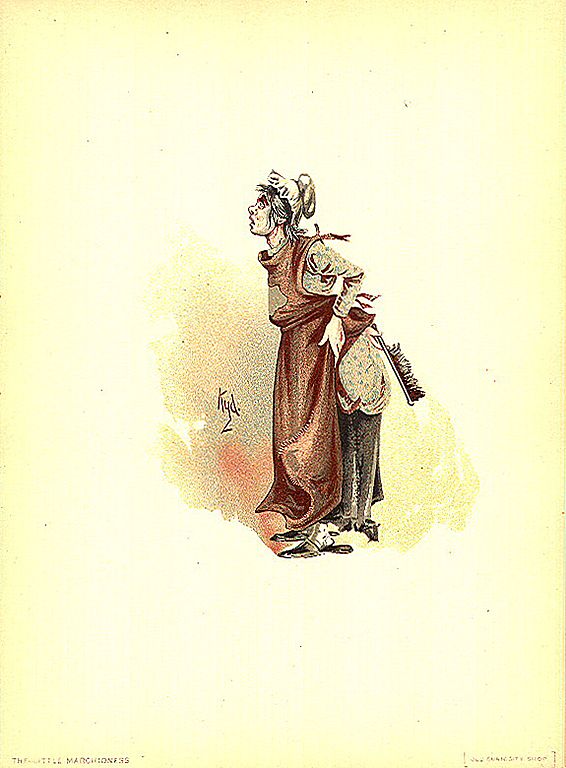

The most miserable of all marchionesses: a poor abused servant in Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop.

An unexpected sense development of the noun mark can be seen in the Scandinavian languages. One need not know any of them to notice the country name Denmark. Old Icelandic mörk (this is modernized spelling) meant “forest.” In present day Scandinavian languages, mark usually means “a piece of land; field,” but “forest” and “uncultivated land” have also been attested. Jacob Grimm believed that “forest” might be the earliest sense of mark, but it was probably not. Rivers, mountains, and wooded areas used to separate and still separate countries. Although a thick forest is a natural boundary, it is curious that Scandinavian had lost the sense so prominent elsewhere. Yet its close cognate turns up in compounds, such as Old Icelandic al-merki “common land held by the community; commons” and landa-merki “a boundary sign” (but landa-mark also existed!). Denmark may have acquired its name after the forests that covered its territory had been largely cleared. In any case, the same Scandinavian noun (mark) can mean both “forest” and “arable land.”

Some words hold great attraction to foreigners. Germanic mark- was borrowed not only by Romance but also by Finnish speakers: in Finnish, markku occurs in place names. Nor was it isolated when it was coined. Its obvious Latin cognate is margo “margin.” The other candidates for relationship with mark are less certain. The word’s ancient root may have meant “to divide.”

Here ends my story of the marquis, “captain of the marches,” a man presiding over a “mark.” As is well-known, his wife or widow is called marchioness.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Portrait of Madame de Pompadour by François Boucher, 1756. Alte Pinakothek. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) The Marchioness 1889 Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop character by Kyd (Joseph Clayton Clarke). From “Character Sketches from Charles Dickens, Pourtrayed by Kyd”. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Marquises and other important people keeping up to the mark appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlanaP,

on 12/22/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

new testatment,

Marc Z. Brettler,

Peter Enns,

luke wrote,

luke’s,

traditions—jewish,

Bible and the Believer,

brettler,

Daniel J. Harrington,

enns,

harrington,

historical biblical context,

How to Read the Bible Critically and Religiously,

Mark,

matthew,

Christmas,

Religion,

bible,

John,

jesus,

luke,

Humanities,

bethlehem,

*Featured,

Add a tag

By Daniel J. Harrington, S.J.

The New Testament contains two Christmas stories, not one. They appear in Matthew 1–2 and Luke 1–2. They have some points in common. But there are many differences in their characters, plot, messages, and tone.

In the familiar version of the Christmas story, Mary and Joseph travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem. Because there was no room in the inn, the baby Jesus is born in a stable and placed in a manger. His humble birth is celebrated by choirs of angels and shepherds, and he is given precious gifts by the mysterious Magi. This version freely blends material from the two biblical accounts. It has become enshrined in Christmas carols and stable scenes as well as the liturgical cycle of readings during the Christmas season.

Giotto’s “Nativity, Birth of Jesus” from Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel, Padua, Italy c. 1304-1306.

My purpose here is not to criticize blending the two Christmas stories or to debate the historicity of the events they describe. What I do want to show is that by harmonizing the two stories we may be missing points that were especially important for Matthew and Luke, respectively. I want also to suggest that appreciating each biblical account separately might open up new perspectives on the infancy narratives for people today.

In The Bible and the Believer: How to Read the Bible Critically and Religiously, Marc Z. Brettler, Peter Enns, and I explore how each of our religious traditions—Jewish, Evangelical, and Catholic—tries to bring together the modern historical-critical reading of the Bible and contemporary religious faith and practice. There are, of course, many differences among us. But there are some principles we hold in common: the value of reading biblical texts in their original historical settings, the need for careful analysis of the literary dimensions of each text, and respect for what seems to have been the intentions of the original author. Applying these principles to the two Christmas stories in the New Testament will reveal more clearly their historical significance, distinctive literary character, and theological riches.

Matthew wrote his Gospel in the late first century CE, perhaps in Antioch of Syria. He was a Jewish Christian writing primarily for other Jewish Christians. He wanted to show that the legacy of biblical Israel was best fulfilled in the community formed around the memory of Jesus of Nazareth. Now that the Jerusalem temple had been destroyed and Roman control over Jews was even tighter, all Jews had to face the question: how is the heritage of Israel as God’s people to be carried on? Matthew’s answer lay in stressing the Jewishness of Jesus.

This setting helps to explain why Matthew told his Christmas story as he did. He begins with a genealogy that relates Jesus to Abraham and David, while including several women of dubious reputation who nonetheless highlight the new thing God was doing in Jesus. Next, he explains how the virginal conception of Jesus through the Holy Spirit fulfilled Isaiah’s prophecy (7:14), and how Jesus the Son of God became the legal Son of David through Joseph. Besides Jesus, Joseph is the main character in Mathew’s Christmas story. Guided by dreams like his biblical namesake, he is the divinely designated protector of Mary and her child Jesus.

The Magi story in Matthew 2 is part of a larger sequence that involves danger for the newborn child and his parents. When King Herod hears about the child “King of the Jews” as a potential rival for his power, he seeks to have Jesus killed. As a result the family flees to Egypt, while Herod orders the execution of all boys under two years old in the area of Bethlehem. Only after Herod’s death does the family return to the Land of Israel, though to Nazareth rather than Bethlehem. At each point in their itinerary, the family is guided by dreams and texts from the Jewish Scriptures.

In his Christmas story Matthew wants us to learn who Jesus is (Son of Abraham, Son of David, Son of God) and how he got from Bethlehem to Nazareth. Thus he establishes the Jewish identity of Jesus, while foreshadowing the mystery of the cross and the inclusion of non-Jews in the church. The tone is serious, somber, and foreboding.

Luke wrote his Gospel about the same time as Matthew did (but independently), in the late first century CE. He composed two volumes, one about Jesus’ life and death (Luke’s Gospel), and the other about the spread of Christianity from Jerusalem to Rome (Acts of the Apostles). The dynamic of the two books is captured by words now in Luke 2:32 taken from Isaiah (42:6; 46:13; 49:6): “a light for revelation to the Gentiles [Acts], and for glory to your people Israel [the Gospel].”

While in his prologue (1:1-4), Luke shows himself to be a master of classical Greek, in his infancy narrative he shifts into “Bible Greek,” in the style of the narrative books of the Old Testament in their Greek translations. Also there are many characters besides Jesus: Zechariah and Elizabeth, John the Baptist, Mary, and Simeon and Anna, as well as various angels and shepherds. These figures represent the best in Jewish piety. Thus Luke creates an ideal picture of the Israel into which Jesus is born.

In the gross structure of his infancy narrative, Luke seems intent on comparing John the Baptist and Jesus. His point is that while John is great, Jesus is even greater. So the announcement of John’s birth as the forerunner of the Messiah is balanced by the announcement of Jesus’ birth as the Son of the Most High (1:5-25; 1:26-56). And so the account of John’s birth and naming is balanced by the birth and naming of Jesus as Savior, Messiah, and Lord (1:57-80; 2:1-40).

Luke portrays Jesus and his family as observant with regard to Jewish laws and customs. At the same time, there are subtle “digs” at the Roman emperor and his clams to divinity. The narratives are punctuated by triumphant songs of joy. They are well known by their traditional Latin titles: Magnificat (1:46-46), Benedictus (1:68-79), and Nunc dimittis (2:29-32). These are pastiches of words and phrases from Israel’s Scriptures, and they serve to praise the God of Israel for what he was doing in and through Jesus.

With his infancy narrative, Luke wants to root Jesus in the best of Israelite piety, while hinting at Jesus’ significance for all the peoples of the world. That is why Luke’s genealogy of Jesus (3:23-38) goes back beyond Abraham all the way to Adam. Luke’s infancy narrative has provided the framework for the traditional “Christian story.” Its tone is upbeat, celebratory, and even romantic.

I have shown one way to read the Christmas stories of Matthew and Luke. It is a way that respects their historical contexts, literary skills, and intentions. It is not the only way. Indeed, during this Christmas season I will be celebrating (God willing) the traditional Christmas story in the two parishes in which I serve regularly as a Catholic priest. What I hope to have shown here is that there is more to the biblical Christmas stories than gets included in the traditional account.

Daniel J. Harrington, S.J., is professor of New Testament at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry, and co-author (with Marc Z. Brettler and Peter Enns) of The Bible and the Believer: How to Read the Bible Critically and Religiously.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Two Christmas stories: An analysis of New Testament narratives appeared first on OUPblog.

By Steve Morris

With just over a week left until Mark Millar’s Kapow Comic-Con returns for 2012 (you’re going, right? See you there — I’ll be the handsome guy with glasses, you can’t miss me), it might be worth going over all the latest announcements the man himself has been making recently. From convention guests to comic-book announcements, he’s been characteristically busy over the past few days, with many an update popping up on his twitter feed.

Most of these are related to his Icon series Kick-Ass, which seems to have become his primary focus over the past few weeks. With the completion of the first and second mini (which is actually the third part of the story – we’ll get to that in a second), Millar’s been ramping up to the imminent launch of his spin-off story, ‘Hit-Girl’. Drawn by John Romita Jr (co-creator of Kick-Ass, who replaced initially announced artist Leandro Fernandez on the title at Millar’s request), this is a five-issue miniseries starting this month. It stars the eponymous underage Chloe Moretz lookalike antihero as she goes about the business of, y’know, murdering people in the name of justice.

Issue #1 comes with a cover from Phil Noto, released only a few days ago by Millar, which pretty much sets the scene for what’ll be to come from the series. It’s a little reminiscent of Game of Thrones, which is rather appropriate as I imagine people are going to get their heads lopped off at random, in true HBO fashion. The mini is set between the events of Kick-Ass and Kick-Ass 2 (which, it’s just been announced, is in development as a film by Universal), you see, meaning fans waiting for some kind of trilogy conclusion to the Red Mist/Kick-Ass battle will have to wait until later on in the year to get their satisfaction and swears.

Hit-Girl sees the main character trying to make it by at school, without snapping and killing people. After seeing her dad die and going on a murderous rampage of revenge as betrayed tweenagers are wont to do, this change of pace is something Millar has been wanting to try for a while now, as it’ll let him delve into the character and explain her origin story for readers. There’ll be an exclusive art preview over on CBR later tonight, so you can get yourself up to speed then.

Does that help? Now when you bump into Mark Millar after being dazzled by my bi-focular good looks at Kapow, you’ll have something to talk to him about! That’s in-between your trips to go see the creators of Arkham City on panel, Audiences with Nick Frost and Warren Ellis, waving at Emma Vieceli, meeting and greeting Jonathan Ross, Scott Snyder and Oliver Coipel, and ‘treating’ C.B. Cebulski to a look at your art portfolio, of course.

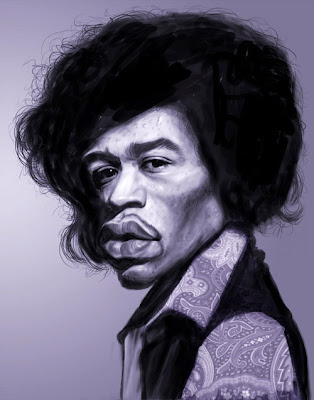

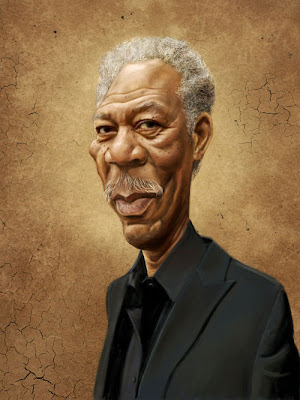

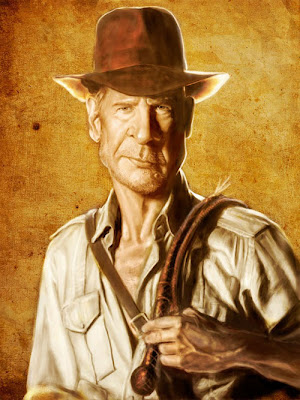

Detroit illustrator Mark Hammermeister is one skilled artist with the pixels. This seriously talented, digital painter is laying down some seriously fantastic, stylized digital art. Look at the level of detail in that Jimi Hendrix illustration below. Look at the pattern in the shirt and the individual strands of hair! Mark wrote on his blog that it took him three hours to do this painting in Photoshop. Three hours – are you kidding me? It was painted over a ballpoint pen sketch. If this took Mark only three hours to create - what can he do in eight – recreate the Sistine Chapel? Hammermeister style!

The images below I could let go on forever. They're just so incredible. Wouldn't you agree?

By: SarahN,

on 11/9/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Health,

History,

Biography,

A-Featured,

Medical Mondays,

asthma,

Biographies of Disease,

Mondays,

Medical,

of,

biographies,

Jackson,

disease,

Mark,

Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company,

Mark Jackson,

respiratory,

inhalation,

Add a tag

Mark Jackson is Professor of the History of Medicine and Director of the Centre for Medical History at the University of Exeter. His newest work, Asthma: The Biography, is a volume in our series Biographies of Disease which we will be looking at for the next few week (read previous posts in this series here). Each volume in the series tells the story of a disease in its historical and cultural context – the varying attitudes of society to its sufferers, the growing understanding of its causes, and the changing approaches to its treatment. In the excerpt below Jackson relays the story of Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company.

On 7 December 1889, an American inventor, Frederick Augustus Roe, obtained a patent for a device that was designed both to cure and to prevent not only the deadly strain of influenza that was sweeping across Europe  from Russia, but also a wide range of other respiratory complaints, including catarrh, bronchitis, coughs and colds, croup, whooping cough, hay fever and asthma. Sold from offices in Hanover Square in London for ten shillings, the Carbolic Smoke Ball comprised a hollow ball of India rubber containing carbolic acid powder. When the ball was compressed, a cloud of particles was forced through a fine muslin or silk diaphragm to be inhaled by the consumer. Boosted by testimonials from satisfied customers and endorsements from prominent doctors, Roe was sufficiently confident that the contraption would prevent influenza that, in several advertisements placed in the Illustrated London News and the Paul Mall Gazette during the winter of 1891, he offered to pay £100 to any person who contracted influenza ‘after having used the ball 3 times daily for two weeks according to the printed descriptions supplied with each ball’. As if to demonstrate the sincerity of his offer, Roe claimed to have deposited £1,000 with the Alliance Bank in Regent Street.

from Russia, but also a wide range of other respiratory complaints, including catarrh, bronchitis, coughs and colds, croup, whooping cough, hay fever and asthma. Sold from offices in Hanover Square in London for ten shillings, the Carbolic Smoke Ball comprised a hollow ball of India rubber containing carbolic acid powder. When the ball was compressed, a cloud of particles was forced through a fine muslin or silk diaphragm to be inhaled by the consumer. Boosted by testimonials from satisfied customers and endorsements from prominent doctors, Roe was sufficiently confident that the contraption would prevent influenza that, in several advertisements placed in the Illustrated London News and the Paul Mall Gazette during the winter of 1891, he offered to pay £100 to any person who contracted influenza ‘after having used the ball 3 times daily for two weeks according to the printed descriptions supplied with each ball’. As if to demonstrate the sincerity of his offer, Roe claimed to have deposited £1,000 with the Alliance Bank in Regent Street.

In November 1891, Louisa Elizabeth Carlill, the wife of a lawyer, purchased a Carbolic Smoke Ball in London and carefully followed the instructions for use. When Mrs Carlill contracted influenza the following January, her husband wrote to Roe claiming the ‘reward’ offered in the advertisements. Suggesting that the claim was fraudulent, Roe refused to pay and provided Mr Carlill with the names of his solicitors. In the resulting legal case, initially heard in the court of Queen’s Bench and subsequently reviewed by Appeal Court, the dispute did not revolve primarily around whether the plaintiff had used the device correctly or indeed whether or not she had contacted influenza; these issues were accepted largely as fact. Rather, legal arguments focused on whether the advertisement constituted a valid offer, rather than ‘a mere puff’, as Lord Justice Bowen neatly put it, and whether Mrs Carlill’s use of the smoke ball constituted acceptance of that offer. By deciding unanimously in Mrs Carlill’s favour, the English courts set a precedent regarding unilateral contracts that continued to inform the legal doctrines of offer and acceptance, consideration, misrepresentation, and wagering throughout the twentieth century.

While Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Company became a celebrated moment in legal history, it al

By: Rebecca,

on 9/15/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

war,

American History,

A-Featured,

Vietnam,

Mark,

World History,

perspective,

prophecy,

Bradley,

Philip,

Mark Philip Bradley,

Add a tag

Mark Philip Bradley is Associate Professor of History at the University of Chicago. His most recent book, Vietnam at War, looks at how the Vietnamese themselves experienced the conflicts,  showing how the wars for Vietnam were rooted in fundamentally conflicting visions of what an independent Vietnam should mean that in many ways remain to this day. In the excerpt below, from the introduction, Bradley begins to paint the Vietnamese perspective of the conflict.

showing how the wars for Vietnam were rooted in fundamentally conflicting visions of what an independent Vietnam should mean that in many ways remain to this day. In the excerpt below, from the introduction, Bradley begins to paint the Vietnamese perspective of the conflict.

In the early 1990 a short story by a young author, Tran Huy Quang, entitled ‘The Prophecy’ (’Ling Nghiem’), appeared to great interest in Hanoi. It told the tale of a young man named Hinh, the son of a mandarin, who longed to acquire the magical powers that would one day enable him to lead his countrymen to their destiny. The destiny itself does not particularly concern Hinh, but he is intent upon leading the Vietnamese people to it. In a dream one evening, Hinh meets a messenger from the gods, who tells him to seek out a small flower garden. Once he reaches the garden, Hinh is told, he should walk slowly with his eyes fastened on the ground to ‘look for this’. It will only take a moment, the messenger tells Hinh, and as a result he will ‘possess the world’.

When he awakens, Hinh finds the flower garden and begins to pace, looking downward. Slowly a crowd gathers, first children, then the disadvantaged of Vietnamese society: unemployed workers, farmers who had left their poor rural villages to find work in the city, cyclo drivers, prostitutes, beggars, and orphans. Watching Hinh, they ask in turn, ‘What are you looking for?’ He replies, ‘I am looking for this.’ Hopeful of turning up a bit of good luck, they join him, and soon multitudes of people are crawling around in the garden. Hinh looks around at the crowd searching with him and believes the prophecy has been fulfilled: he possesses the world. With that realization Hinh goes home.

To Vietnamese readers the story was immediately recognized as a parable, with Hinh representing Ho Chi Minh, the pre-eminent leader of the twentieth-century Vietnam. The prophecy was seen as coming from a secular god, Karl Marx. ‘This’ was the promise of a socialist future, which the author of ‘The Prophecy’ and many of his readers in Hanoi increasingly believed to be a hollow one. For them, socialist ideals did enable Vietnamese revolutionaries to develop a mass following and establish an independent state, throwing off a century of French colonial rule. But in the aftermath of some thirty years of war against the French and the Americans, their hopes for a more egalitarian and just society appeared to remain unfulfilled.

…In truth, there were many Vietnam wars, among them an anti-colonial war with France, a cold war turned hot with the United States, a civil war between North and South Vietnam and among southern Vietnamese, and a revolutionary war of ideas over the vision that should guide Vietnamese society into the post-colonial future. The contest of ideas began long before 1945 and persists to the present day in yet another war, this one of memory over the legacies of the Vietnam wars and the stakes of remembering and forgetting them.

For most Vietnamese, the coming of French colonialism in the late nineteenth century raised profound questions about their very survival as a people and pointed to the need to rethink fundamentally the neo-Confucian political and social order upon which Vietnamese society has rested. As one young Vietnamese asked in a 1907 poem:

Why is the roof over the Western universe the broad land and skies;

While we cower and confine ourselves to a cranny in our house?

Why can they run straight, leap far,

While we shrink back and cling to each other?

Why do they rule the world,

While we bow our heads as slaves?

Throughout the twentieth century, in both war and at peace, and into the twenty-first century, the Vietnamese have searched for answers to the predicaments posed by colonialism and the struggle for independence. As they have done so, a variety of Vietnamese actors have appropriate and transformed a fluid repertoire of new modes of thinking about the future - social Darwinism, Marxist-Leninism, social progressivism, Buddhist modernism, constitutional monarchy, democratic republics, illiberal democracies, and market capitalism to name just a few - to articulate and enact visions for the post-colonial transformation of urban and rural Vietnamese society. But the end of the Vietnam wars did not bring a final resolution to these competing visions. When North Vietnamese tanks entered Saigon on 30 April 1975 to take the surrender of the American-backed South Vietnamese government, Vietnam was reunified as a socialist state. The long war for independence was over. Yet even today, as the searchers in ‘The Prophecy’ suggest, the meanings according to ‘running straight and leaping far’ remain deeply contested. In one of many present-day paradoxes, the Vietnamese state seeks to develop a market economy as it maintains its commitment to socialism, while an increasingly heterodox Vietnamese civil society simultaneously embraces the global economy, years for the unfulfilled promises of socialist egalitarianism, and reinvents many of the spiritual and familial practices the socialist state spent the war years trying to stamp out. Indeed, a walk today through a typical city block at the centre of Hanoi or Saigon, a block in which a refurbished Buddhist temple might be flanked by a Seven-Eleven store on one side and the local community party headquarters on the other, quickly reveals these everyday contradictions and tensions…

By: Rebecca,

on 7/20/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reading Room,

Bryant,

John R. MacArthur,

MacArthur,

Sawyer,

Harper\ s,

Literature,

Current Events,

Free,

A-Featured,

A-Editor's Picks,

Prose,

Leisure,

OWC,

Bryant Park,

Harper's Magazine,

Reading,

Magazine,

read,

John,

Tom Sawyer,

Mark Twain,

Oxford University Press,

R,

Park,

Tom,

Mark,

lunch,

Room,

Twain,

Add a tag

What are you doing during lunch tomorrow? If it involves sitting at your desk eating a sandwich consider joining us in Bryant Park. Oxford University Press has teamed up with the Bryant Park Reading Room to host a FREE discussion of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer led by John R. MacArthur, publisher of Harper’s Magazine and author, most recently, of You Can’t be President: The Outrageous Barriers to Democracy in America. In the blog post after the break MacArthur introduces us to the relationship between Harper’s and Mark Twain.

So be sure to come to the Bryant Park Reading Room (northern edge of the park), Tuesday, July 21st from 12:30 p.m. to 1:45 p.m. The rain venue (don’t worry we are doing our best no-rain dances) is The General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen Building, 20 West 44th Street. Sign up in advance and receive a FREE copy of the Oxford World’s Classic, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (offer is limited while supply lasts).

The histories of Mark Twain, William Dean Howells and Harper’s Magazine are so intimately linked, so important to the fabric of the magazine, that I talk about Twain and Howells around the office as if they were still alive. The other day I told a staff meeting that as long as I was running Harper’s, it would remain a literary magazine that also publishes journalism — not the other way around — because of Howells’s and Twain’s ever-present legacy.

Howells met Twain in 1869, three years after Twain had published his first long narrative in Harper’s, “43 Days in an Open Boat.” As the future literary editor of Harper’s recalled, “At the time of our first meeting…Clemens (as I must call him instead of Mark Twain, which seemed always somehow to mask him from my personal sense) was wearing a sealskin coat, with the fur out, in the satisfaction of a caprice, or the love of strong effect which he was apt to indulge through life.” It’s no coincidence that for our special 150th anniversary issue in 2000, we constructed a cover photo of Twain in his dandy suit facing Tom Wolfe in his dandy suit.

Clemens and Howells became good friends and in 1875 the genius from Hannibal asked Howells to read the manuscript of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. “I am glad to remember that I thoroughly liked The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” Howells wrote, “and said so with every possible amplification. Very likely, I also made my suggestions for its improvement; I could not have been a real critic without that; and I have no doubt they were gratefully accepted and, I hope, never acted upon.” Howells was underrating his influence on Twain, who penned over 80 pieces for Harper’s. As a critic and a fine novelist in his own right, Howells was correct — Tom Sawyer is a great American novel. Indeed, not everyone agrees that it’s any less of an achievement than the more widely acclaimed (at least in serious literary circles) Huckleberry Finn. I’m looking forward to talking about the book next week and finding out the answer to a number of questions: for example, precisely how old is Tom Sawyer? I assume the Twain scholars in the audience will enlighten me on this and other matters.

By: Rebecca,

on 7/7/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

women,

in,

Hillary Clinton,

power,

Sarah,

Obama,

Clinton,

Mark,

Barack,

Hillary,

Lady,

Palin,

Sarah Palin,

Mark Sanford,

Iron Lady,

women in power,

double bind,

Iron,

Sanford,

Add a tag

Elvin Lim is Assistant Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he reflects on Sarah Palin’s resignation. See his previous OUPblogs here.

than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com. In the article below he reflects on Sarah Palin’s resignation. See his previous OUPblogs here.

People love to hate Sarah Palin. I thought she was trouble on the McCain ticket, trouble for feminism, and trouble for the future of the Republican party, but I am troubled at the feeding frenzy that has continued despite Palin’s express desire and efforts to bow out of the negative politics that has consumed her governorship.

The speculation about what exactly Palin is up to is itself revealing - for it comes attached to one of two possible postulations - neither of which are charitable. Either Palin is up to no good, or she is completely out of her mind. Even in surrender Palin is hounded. Either she is so despicable that post-political-humous hate is both valid and necessary or she is so dangerous that she must be defeated beyond defeat.

Even Governor Mark Sanford got a day or two of sympathy from his political opponents before he admitted to other extra-marital dalliances and referred to his Argentinian belle as his “soul-mate.” Sarah Palin was accorded no such reprieve. Yes, I think gender is entirely relevant here.

Feminist scholars have studied the double-bind of woman political leaders for a while now. Women leaders are faced with a dilemma a still-patriachical political world imposes on them: women must either trade their likeability in return for male respect; or they preserve their likeability but lose men’s respect for them in exchange. When it comes to women in positions of political power in the world that we know, they cannot be both likeable and respected. Unlike men, they cannot have their cake and eat it as well. This is not the world I like, but it is the world I see.

Let me draw an unlikely parallel to make the point. People love to hate another woman that we saw a lot of in 2008 - Hillary Clinton. Like Palin, she was to her detractors the she-devil to whom evil intentions were automatically assigned for every action. But unlike Palin, she was respected and feared - she was everything Sarah Palin was not. What Palin lacked in terms of likeability she possessed in terms of respect (or at least reverent fear). No one underestimated Hillary Clinton, no one doubted her ambition. And of course, as Barack Obama put it in one of their debates, she was only “likeable enough.” Clinton was respected as a force to be reckoned with, but she paid her dues in terms of likeability. Just like the Virgin Queen and the Iron Lady, she could only be respected if she surrendered her congeniality.

Palin stands at the other end of the double-bind. Where Palin was in need of respect she gained in terms of likeability. She was the pretty beauty queen loved and beloved by her base, unapologetically espousing a “lip-stick” feminism (in contrast to a grouchy liberal feminism). But what she enjoyed in terms of likeability she lost in terms of respect. If there was one thing her detractors have done consistently, it has been to mock her. She was the running joke on Saturday Night Life, and now, a laughing stock even amongst some Republicans who see her as a quitter and a thin-skinned political lightweight. Strangely enough, Sarah Palin is Hillary Clinton’s alter-ego. Where Clinton is perceived as strong, Palin is seen as weak; whereas Clinton turns off (a certain sort of) men, Palin titillates them.

If we lived in a post-feminist, gender-neutral world, the two most prominent women in American politics, Sarah Palin and Hillary Clinton, would not so perfectly occupy the antipodal caricatures of women trapped in the double-bind of our patriachical politics. That they each face one cruel end of the double binds tells us that the two women on opposite ends of the political spectrum sit in the same patriachical boat. So the next time liberals mock Sarah Palin, they should remember that they are doing no more service to feminism than when some conservatives made fun of Hillary Clinton’s femininity allegedly subverted by her pant-suits.

By: Rebecca,

on 3/6/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

oupblog,

Dictionaries,

dictionary,

From A To Zimmer,

prattle,

mark,

peters,

wordlustitude,

ben,

zimmer,

Blogs,

oxford,

gossip,

words,

A-Featured,

Lexicography,

dictionary,

ben,

Dictionaries,

zimmer,

From A To Zimmer,

oupblog,

mark,

prattle,

peters,

wordlustitude,

Add a tag

Mark Peters, the genius behind the blog Wordlustitude in addition to being a Contributing Editor for Verbatim: The Language Quarterly, a language columnist for Babble, and a blogger for Psychology Today, is our guest blogger this week. Below Peters encourages us to make old words hip again.

Did you hear about the nude pictures of Lindsay Lohan and Roger Clemens drinking a human growth hormone/grain alcohol smoothie?

You have? Then let me tell you what my brother’s nanny has been up to with your father’s mechanic in the gazebo. (more…)

Share This

By:

Aline Pereira,

on 7/16/2007

Blog:

PaperTigers

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Harry Potter,

Children's Books,

Young Adult Books,

Deathly Hallows,

Rick Riordan,

children-s books,

Lionboy,

series books for kids,

The Titan-s Curse,

Zizou Corder,

Add a tag

My 10-year-old friend Nicky is the quintessential bribable reader. When I went shopping with his mom and older sister recently, Nicky patiently spent several contented hours in a corner of a shoe department, burrowing into The Titan’s Curse, the latest volume in Rick Riordan’s Olympian-themed Percy Jackson series. Nicky’s mom had sagely bought this hefty tome for him in anticipation of our shopping spree.

For Nicky’s generation, multicultural includes imaginary worlds. Brought up on Harry Potter and undaunted by huge page numbers, he loves books in series. “The Lionboy series [by Zizou Corder] is one of my favorites,” he emailed me. “It’s about a boy who got scratched by a leopard when he was a baby. Ever since then he has been able to speak with cats. After his parents were kidnapped his journey takes him all over the world, including his native continent, Africa. He soon finds out that it’s very hard to get 5 circus lions from France to Africa at the same time he’s trying to save his parents from a mysterious corporation before they get brainwashed.”

For Nicky’s generation, multicultural includes imaginary worlds. Brought up on Harry Potter and undaunted by huge page numbers, he loves books in series. “The Lionboy series [by Zizou Corder] is one of my favorites,” he emailed me. “It’s about a boy who got scratched by a leopard when he was a baby. Ever since then he has been able to speak with cats. After his parents were kidnapped his journey takes him all over the world, including his native continent, Africa. He soon finds out that it’s very hard to get 5 circus lions from France to Africa at the same time he’s trying to save his parents from a mysterious corporation before they get brainwashed.”

Nicky will be busy with Deathly Hallows for the next few weeks, of course, but until he gets hooked on a series, how does he decide what books to read? “This might sound weird, but I usually choose a book by its cover. If the cover looks interesting, I read the summary.” Nicky promises to glance up from his latest read from time to time to comment again for PaperTigers on books he loves. Meanwhile, for a list of series books for kids, click here. And here, for Stephen King’s lovely goodbye to Harry Potter.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

from Russia, but also a wide range of other respiratory complaints, including catarrh, bronchitis, coughs and colds, croup, whooping cough, hay fever and asthma. Sold from offices in Hanover Square in London for ten shillings, the Carbolic Smoke Ball comprised a hollow ball of India rubber containing carbolic acid powder. When the ball was compressed, a cloud of particles was forced through a fine muslin or silk diaphragm to be inhaled by the consumer. Boosted by testimonials from satisfied customers and endorsements from prominent doctors, Roe was sufficiently confident that the contraption would prevent influenza that, in several advertisements placed in the Illustrated London News and the Paul Mall Gazette during the winter of 1891, he offered to pay £100 to any person who contracted influenza ‘after having used the ball 3 times daily for two weeks according to the printed descriptions supplied with each ball’. As if to demonstrate the sincerity of his offer, Roe claimed to have deposited £1,000 with the Alliance Bank in Regent Street.

from Russia, but also a wide range of other respiratory complaints, including catarrh, bronchitis, coughs and colds, croup, whooping cough, hay fever and asthma. Sold from offices in Hanover Square in London for ten shillings, the Carbolic Smoke Ball comprised a hollow ball of India rubber containing carbolic acid powder. When the ball was compressed, a cloud of particles was forced through a fine muslin or silk diaphragm to be inhaled by the consumer. Boosted by testimonials from satisfied customers and endorsements from prominent doctors, Roe was sufficiently confident that the contraption would prevent influenza that, in several advertisements placed in the Illustrated London News and the Paul Mall Gazette during the winter of 1891, he offered to pay £100 to any person who contracted influenza ‘after having used the ball 3 times daily for two weeks according to the printed descriptions supplied with each ball’. As if to demonstrate the sincerity of his offer, Roe claimed to have deposited £1,000 with the Alliance Bank in Regent Street.

Man, totes mcgoats love her costume. Except that lock (which is brilliant) would smack her in the face while she jumped around and villains could grab hold of it easily.

Oh right it’s a comic book about a blood thirsty thirteen year old who can throw knives and never miss. Never mind….

Knowing there is new Kick-Ass stuff gives me another reason to get up in the morning.

I don’t know Miller but to my eyes his marriage of talent and business acumen set a very positive example for “mass-market” comics.

More Kick Ass in the horizon, always a good thing.

Kinda wondering why he’s still publishing from Marvel (Icon) though, thought he was leaving them for Millarworld publishing or something.