new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Pacing, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 62

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Pacing in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Candy Gourlay,

on 4/24/2016

Blog:

Notes from the Slushpile

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Learning,

Plot,

Structure,

Pacing,

Margo Lanagan,

confessions,

Michelle Magorian,

Bernard Beckett,

Sarah Waters,

Jo Wyton,

Elizabeth Wein,

Amy Butler Greenfield,

Add a tag

I typically open any given manuscript I’m working on knowing one thing: I haven’t got much time to work on it.

Writing exists around that other time-consuming thing in my life: a full time job. And I love my job, so that’s OK by me.

But is does mean that when I come to work on a manuscript, I feel under pressure to do something Great with it.

I jump right in. Maybe I re-read the last few paragraphs I wrote, maybe I just get on with it. Maybe I pick up an existing scene, maybe I write a new one. Maybe it’s planned, maybe it’s not.

Whilst I have usually planned the plot out, I have always been someone more comfortable with winging it than properly planning it.

And that’s fine, except that I was reading

Candy Gourlay’s post from a few weeks ago and felt the need to try to do things a little differently.

Why don’t I plan more? Is it because it doesn’t work for me, or because in the limited time I have I prioritise the writing itself? Or is it – gulp – because I’ve never taken the time to learn how?

In an odd turn of events, I currently have the time, and it’s coincided wonderfully with having the inclination. Sitting next to me on my desk: Story by Robert McKee,

Writing Children’s Fiction by Yvonne Coppard and Linda Newbery (from whom I have already been lucky enough to glean pearls of wisdom and kindness generously gifted on an Arvon course), On Writing by Stephen King and Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose.

Just as importantly I have surrounded myself by my favourite books, and have gone through each wondering for the first time why exactly they stick in my mind as favourites. Michelle Magorian's Goodnight Mister Tom and Elizabeth Wein's

Code Name Verity for the depth of friendship invoked, Margo Lanagan's

Tender Morsels and Bernard Beckett's

August for their wondrous use of language, Amy Butler Greenfield's

Chantress for its use of setting to reflect the characters perfectly – the list goes on.

Reading these books again and trying to break them down goes against instinct, but as Sarah Waters wrote in a 2010 Guardian article, “Read like mad. But try to do it analytically – which can be hard, because the better and more compelling a novel is, the less conscious you will be of its devices. It’s worth trying to figure those devices out, however: they might come in useful in your own work.”

Diving head-first into learning how to write better, rather than spending the time writing the manuscript itself, feels somewhat intimidating, but cometh the time, cometh the writer. Probably.

Getting the pacing of your story right is a balancing act.

http://writershelpingwriters.net/2016/02/19038/

Courtesy: Jeremy Segrott @ Creative Commons

I’d like to start this post by stating an opinion that I think pretty much everyone shares: Pacing Sucks. When you get it right, no one really notices. I mean, how many times have you read a 5-star review that went on and on about the awesome pacing? On the other hand, when the pacing’s off, it’s obvious, but not always easy to pinpoint; you’re just left with this vague, ghostly feeling of dissatisfaction. One thing, though, is certain: if the pacing is wrong, it’s definitely going to bother your readers, so I thought I’d share some tips on how to keep the pace smooth and balanced.

1. Current Story vs. Backstory. Every character and every story has backstory. But the relaying of this information almost always slows the pace because it pulls the reader out of the current story and plops them into another one. It’s disorienting. And yet, a certain amount of backstory is necessary to create depth in regards to characters and plot. To keep the pace moving, only share what’s necessary for the reader to know at that moment. Dole out the history in small pieces within the context of the current story, and avoid narrative stretches that interrupt what’s going on. Here’s a great example from Above, by Leah Bobet:

The only good thing about my Curse is that I can still Pass. And that’s half enough to keep me out of trouble. But tonight it’s not the half I need because here’s Atticus, spindly crab arms folded ‘cross his chest, waiting outside my door. His eyes glow dim-shot amber—not bright, so he’s not mad, just annoyed and looking to be mad.

Bobet could have taken a lengthy paragraph to explain that certain people in this world have curses that are really mutations, that Atticus has crab claws for hands and his eyes glow when he gets angry. But that would’ve slowed the pace and been boring. Instead, Bobet wove this information into the current story—showed Atticus leaning against the door, showed his crustacean claws and his freaky, glowing eyes so the reader knows that he’s a mutant and, to the narrator, at least, this is normal. This is an excellent example of the artful weaving of backstory into the present story.

2. Action vs. Exposition/Internal Dialogue. Action is an accelerant. It keeps the pace from dragging. Granted, there will be places in your story that are inherently passive, where characters have to talk, or someone needs to think things out. The key is to break up these places with movement or activity. Characters should be in motion—smacking gum or doodling or fidgeting— while talking. Give them something to do during their thoughtful moments, whether it’s peeling carrots or painting a picture. These bits of action are like an optical illusion, fooling the reader into thinking something’s happening, when really, nothing’s going on. This is one scenario when readers actually prefer to be fooled, so make sure to energize those narrative stretches with action.

3. Conflict vs. Downtime. On the flip side, you can’t have a story that’s all go and no stop. One might think that since action is good, more action is better. Not true. Readers need time to catch their breath, to recover from highly emotional or stressful scenes. A good pace is one that ebbs and flows—high action, a bit of recovery, then back to the activity again. Even The Maze Runner, possibly the most active novel I’ve ever read, has its moments of calm. When it comes to conflict and downtime, a definite balance is needed for the reader to feel satisfied.

3. Conflict vs. Downtime. On the flip side, you can’t have a story that’s all go and no stop. One might think that since action is good, more action is better. Not true. Readers need time to catch their breath, to recover from highly emotional or stressful scenes. A good pace is one that ebbs and flows—high action, a bit of recovery, then back to the activity again. Even The Maze Runner, possibly the most active novel I’ve ever read, has its moments of calm. When it comes to conflict and downtime, a definite balance is needed for the reader to feel satisfied.

4. Keep Upping the Stakes. We know that conflict is important—so important that every single scene needs it. But for conflict to be effective, it needs to escalate over the course of the story. To keep the reader engaged, each of the major conflict points needs to be bigger, more dramatic, and with stakes that are more desperate. This is exemplified in Ruta Sepetys’ excellent Between Shades of Gray, a historical fiction novel about the deportation of a Lithuanian family during World War II. It starts out ominous enough, with the family being forced from their home. Over the course of the story, they’re moved by cattle car across the continent, relocated to a forced labor camp, and eventually reach their final destination—a camp in the Arctic Circle where they’re expected to survive the elements with whatever resources they can scrounge. Clearly, lots of other conflict is interspersed, but when it comes to the major points, each one should have greater impact than the last.

5. Condense the timeline. When possible, keep your timeline tight. If it gets too spread out, the story will inevitably drag. It’s also hard, in a story that covers a long span, to keep things smooth; there will be time jumps of weeks or months or even years between scenes. Too many of these give the story a jerky feel. So when it comes to the timeline, condense it as much as possible to keep the pace steady.

For sure, pacing is tricky, but I’ve found these nuggets to be helpful in maintaining a good balance. What other tips do you have for keeping your story moving at the right pace?

The post Getting the Pacing Right appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS™.

Even if you're not an illustrator, it's important to make a dummy in order to check the pacing of your picture book.

http://writersrumpus.com/2013/11/22/3-ways-to-pace-your-picture-book/

I can’t stop thinking about the line Emily left us with yesterday, this one:

They are stories coming from a place of trying to understand, rather than a place where it is understood.

Right?

Welcome back, Emily! Hope you enjoy the rest of our conversation. (And a reminder, click to enlarge any images.)

Can you tell us about the design of the art and the text? I love that your pictures don’t have text on them anywhere, and the page turn with the flower is the only time there’s text away from the bottom. What went into those decisions?

There wasn’t much decision making- that was the problem! Often times I like to work with only a bit of text because type is a whole other ball-park in terms of aesthetics. I have a hard time compromising my space for words- text and fonts and size, all that jazz has to mesh in with the artwork, and it’s hard finding the right voice to match the looks.

My work gets pretty dense, so I find it a lot more difficult to find something that is legible, but still yields to the art. In university I preferred to keep my lines simple and punchy and give a whole page of text to one image- it makes you read everything slower, more thoughtfully. However in the world of big print-run publishing, it is a luxury to use up so much paper! I work on the pacing, but the designers at Flying Eye made a lot of the technical decisions and all the book designing- I think they’ve done beautifully.

What is your favorite piece of art hanging in your home or studio?

I work at home, and my favourite art piece is this ceramic self-portrait bust my Dad made when he was a kid in school. It’s got hair that looks like it was squeezed through a garlic presser- he forgot a bit of hair on the back though, and he made his nostrils with a pencil eraser. It’s a bit creepy, bit primitive cool. Very seventies. Still trying to find the best place to display it.

What are some of your favorite picture books? Both for writing and text and whatever inspires? What is your favorite picture book from childhood?

My favourite old school book is Munro Leaf’s Ferdinand. It is a beauty in text and image- what a fantastic story about the happily peaceful bull. Didn’t want to fight, didn’t want the fame, just wanted the simple pleasures of everyday life. You come across the message of being unique quite a bit in children’s books. Oftentimes it’s a feeling of ‘you’re different’ therefore special, therefore better. I don’t get that passive aggression or hypocrisy with Ferdinand.

For modern, I love Michael Rosen/Quentin Blake’s Sad Book. It isn’t sappy or over the top, it is perfect. No melodrama or silver-linings, just honest. The book feels like it is quietly listening to it’s readers own blues. It brought me real comfort. It is really a gem.

In terms of illustration, I love everything that is Blair Lent. Dreamy.

What’s next for you?

Lots of good things in store at the moment! I have finished a bunch of projects recently, and am still catching my breath.

I just finished A Brave Bear with Walker Books, and Brilliant with Abrams, and I’m now moving on to a book series with Chronicle for easy readers called Charlie and Mouse which is written by Laurel Snyder.

Oh, and did I mention the ever lovely Everything you Need for a Treehouse by THE Carter Higgins?

I am excited about it all, and slowly getting better at juggling everything- at the moment I am trying to doodle personal work (if you don’t maintain this, everything goes bad, you don’t evolve!), little brothers, and treehouses. For boys, I’ve been creeping around my high street and local parks to get inspiration, for tree houses I fondly think of the ones my neighbours and I repeatedly built unsuccessfully. Now I can build one without the necessary requirements of having lumber readily available, knowing how to saw wood, and basic physics!

Exciting, busy, new!

—

Thanks, Emily! It was such an honor to have you here, and I am so, so excited about our future!

Huge thanks to both Emily and Tucker Stone at Flying Eye Books for the images in this post!

By: Carter Higgins,

on 8/25/2015

Blog:

Design of the Picture Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

interview,

storytelling,

Uncategorized,

creative process,

balance,

pacing,

composition,

perspective,

color palette,

white space,

emily hughes,

everything you need for a treehouse,

flying eye,

Add a tag

by Emily Hughes (Flying Eye Books, 2015)

by Emily Hughes (Flying Eye Books, 2015)

Friends, I am beyond awe with this conversation with Emily Hughes. If you aren’t familiar with her work yet, I guarantee you will fall in love with it, with her, with a storytelling brilliance that is out of this world. Here, she lets us know both where stories come from and why they do.

And a note, you’ll definitely want to click on all of these images to enjoy them at their full resolution.

Enjoy!

Can you talk about where this book came from? And what the process was like for its creation?

Can you talk about where this book came from? And what the process was like for its creation?

Lots of things were swimming around in my head when The Little Gardener was being made.

I was back home rereading a book I love, The Growth of the Soil, about a simple self-sufficient man dealing with societal pressures that seem unnecessary. He was the symbol of The Little Gardener, he’s not the personality powerhouse Wild is, he is really just a symbol for the everyman, the underdog, you, me, (my brother thinks the 3rd world) our place as a human. It’s not about him, it’s about his vision, his hopes.

There are a lot more nuances to that, but that is what it is in a very small nutshell.

The process for Gardener was an outpouring, I drew and drew and drew. Because the images are so dense it was a meditative book to make- almost like making a mandala. The story process took a while, but with the images I worked on steadily through, and luckily they worked out with little drafting. That isn’t the usual, but this one felt natural to make, intuitive.

Why do you think your stories are best suited to the form of the picture book? What can you do in this form that you might not be able to in another?

If you look at my bedroom, my backpack, my email inbox, my general manner, you would be able to figure out a good deal about me. Totally scatter-brained.

It is an affliction that makes it tricky to get work done in general. What makes children’s books an appealing medium for me is that there is text to dance with. There is the written skeleton to adhere to- oftentimes my stories have layers that I have built up depending on where I am or what I’ve been thinking of while I work. There is not just one story being told in The Little Gardener. Having text keeps my brain focused when there are other ideas floating about. Because I also draw, I am able to tell the other story lines as well- they are quieter, but are still present for others to interpret if they have patience. It is a good compromise for me.

Narrative has always been an interest, I think telling stories is what I like to do- so the things I’d compare it to would be film, theater, animation, etc. I like doing illustrations for picture books because it’s 2D and doesn’t move. However, if you are really invested you can move them within your head and expand it’s boundaries to a world you truly are interacting with.

One of my favorite things is the cola can that says MADE IN HILO, HI on it. I know that’s where your roots are, and I wonder how that home has shown up in the work that you do? Or if there are other easter-egg-y things that you stick in your work?

Good spotting! Hawaii is always present in my work. I left home for university in England when I was 17, and at that time I was eager for new experiences. Nevertheless, absence makes the heart grow fonder, and I miss the Big Island always. Drawing things from home is indulgent for me- it is time spent reminiscing, it is a means for me to keep connected, grounded.

The cola can was initially modelled after a local company- Hawaiian Sun. The label looks nothing like the original (and I used the non-existent ‘cola’ because I thought it would be easier to translate), but the sun made a symbolic appearance. Those cans are always around- refreshments after soccer games, trips to the beach, the park with cousins. It reminds me of happy outings. I’ll add this bit to my advertising resume…

The house that the humans live in is based on my family home. It’s a plantation-style house that my Grandmother grew up in, as my siblings and I have also done. It’s a special place.

In the scene where the gardener is chasing away the snails, there’s a ‘rubber slipper’ (you guys would call it ‘flip flop’- Hawaii’s preferred footwear of choice) strewn about. It even has the ‘Locals’ tag on it which is the same kind you get at the grocery store. There’s lots of little things from home hidden. I like having the sentimentality there, even if it’s for my own benefit.

It seems like the girl in Wild and this little gardener have some sensibilities in common, like the hope and comfort in this un-tapped-into nature. Are there big-picture-stories you are drawn to creating, both in text and in art?

There are a lot of stories I’d like to tell. I think I start off with a general character and theme and it evolves- the writing is the last part, I think the feeling needs to be understood first.

In my journal these are a few themes I’d written that I want to explore:

Does ‘evil’ exist? Really?

You can, will, should feel every horrible emotion and that’s fine

Kindness trumps all

Looks vs Expectations

It’s all chance for me I think- I might read something, or watch something, or sit blankly staring at the wall even, and most times it is nothing but a murmur. But once in a good while something speaks up.

As for Wild and Gardener, nature serves as a backdrop because it is an ideal to be in sync within our most natural of habitats. Something we all still strive for- a place where we’re needed. Wild is about acceptance and tolerance, issues I was trying to practice myself. Gardener was about keeping hope alive when I was faltering with my own.

They are stories coming from a place of trying to understand, rather than a place where it is understood.

—

Carter, here.

You guys. I keep reading these answers over and over and feel like it’s such a gift to get this glimpse into a storyteller’s heart. Because Emily is fascinating and brilliant and our conversation gave me so much to wrestle with and enjoy, there’s more! Come back tomorrow for the second part. More pictures, more process, more book love.

Whatever you do, get your hands on this book as soon as you can, for hope and home and heart.

Huge thanks to both Emily and Tucker Stone at Flying Eye Books for the images in this post!

We welcome author Amy K. Nichols to the blog today. Amy's here to help us shape up flabby dialogue to tighten our pace. Be sure to check out her upcoming release, While You Were Gone, at the end. Welcome Amy!

Blah Blah Blah: How Dead-End Dialogue Kills Pacing and How to Get Your Story Back Up to Speed by Amy K. Nichols

Of all the problems writers face when revising, one of the most elusive is pacing. Locking into the internal engine of a story can be tricky. We writers tend to overthink our scenes, distrust our instincts, and underestimate our readers. Then we compensate by adding more words, which only gums up the works. As a result, our stories sputter and lag, groaning under the weight of all the stuff we’ve crammed into them. Our critique partners return chapters with comments like,

This section drags, This part lost my interest, What’s the point here?

Ugh. Fixing pacing problems can seem like an unwieldy process. Where do you even begin?

I suggest with dialogue.

In my experience there are three common dialogue problems that result in bogged-down pacing: white noise; perfect questions, perfect answers; and stating the obvious. The good news is, because dialogue stands out visually from the rest of the text, it’s easy to isolate and revise each section individually. Even better news is, each of these problems is pretty easy to fix. Here’s what to look for, and suggestions on getting your story back up on track.

White Noise

Sometimes your characters get to chatting and say a whole lot more than what needs to be said. The result is a slew of words that act like white noise or static, adding nothing to the story. When revising dialogue, look for repeated questions and dwindling comments. For example:

Character 1: Did you watch the finale of Game of Thrones?

Character 2: The one with Snow?

Character 1: Yeah.

Character 2: Yeah.

Character 1: That was crazy, huh?

Character 2: Totally crazy.

Character 1: Yeah.

Authentic character voice is good, but keep in mind that just because people actually talk like this, it doesn’t necessarily make for good reading. Here’s how you might revise such an interaction to keep the story moving:

Character 1: Did you see what happened to Snow on Game of Thrones?

Character 2: Yeah. That was crazy.

Character 1: Totally.

Done. It gets the information to the reader while keeping the authentic voices of the characters. All you’ve lost is the extraneous white noise that slows the pacing. Regardless of whether your dialogue is gripping or inane like this (hopefully it’s gripping), trimming away the excess takes away the drag.

Perfect Questions, Perfect Answers

The second thing to look for are instances where characters continually ask the exact questions necessary for getting information across to the reader or so the next plot point can take place. In other words, a sequence of perfect questions followed by the perfect answers. This is a really easy pattern to fall into, especially in early drafts when you’re trying to figure out the story. We think we’re being crafty, using dialogue to convey information and instigate action, but when your characters always say all the right things at all the right times, it actually stunts the story. It’s like when your windshield is too dry and your wipers make that awful

bbbbrooooarromph noise. For example:

Character 1: Want to go to the movies tonight?

Character 2: That would be great. I’ll pick you up at six.

Character 1: Want to get dinner after?

Character 2: Sure. We can go to Bucky’s Burgers.

Character 1: Isn’t that where Brian works?

Character 2: Yeah. Maybe he’ll see me and ask me out.

Okay, hopefully your writing is a lot more compelling than this, but still, you can see the problem. Perfect questions followed by perfect answers. Sometimes info dumps lurk in these exchanges. There’s nothing in dialogue above that can’t just be shown through the action and progression of the plot. The characters go to the movie, get dinner after, see Brian, and he asks Character 2 out. The work is done visually rather than through stilted dialogue. If you absolutely must keep the exchange, pare it down.

Character 1: Movie tonight? Bucky’s after?

Character 2: Sure. I’ll pick you up at six.

You can use dialogue to set up the action to come without telegraphing what the plot will be. Keep it simple. Keep it moving.

Stating the Obvious

The final problem to look for when revising is sections where your characters say what they already know solely for the reader’s benefit. Writers do this when they question their ability to communicate the story, and/or when they underestimate the readers’ ability to comprehend it. Passages of dialogue that state the obvious cause readers to roll their eyes and think,

We already know this! (Well, that’s how I react anyway.)

If you come across a character stating the obvious, ask yourself the following questions:

- Has any of this been shown in previous scenes or chapters?

- Does this section of dialogue advance the story?

- If I cut this dialogue, will the reader be lost or confused?

If you answer these questions and still feel you need the exchange, revise the section to be as quick and snappy as possible.

Along the same lines, keep an eye out for info dumps. This is when a character (or in some cases, the narrator) stops the story to explain something, such as a character’s backstory or the technical specifications of a spaceship. Because info dumps act like a pause button on your plot, any momentum you’ve built up to that point will be interrupted. When it comes to info dumps, the rule of thumb is to wait as long as possible to include them. Only do an info dump when your reader is so curious and so wanting the information, they’re willing to put up with the interruption.

While fixing pacing can feel like a huge undertaking, starting with these three dialogue problems can be a quick way to jump-start your story and get it moving again.

About the Book:

Eevee is a promising young artist and the governor’s daughter in a city where censorship is everywhere and security is everything. When a fire devastates her exhibition—years in the making—her dreams of attending an elite art institute are dashed. She’s struggling to find inspiration when she meets Danny, a boy from a different world. Literally.

Raised in a foster home, Danny has led a life full of hurt and hardship until a glitch in the universe changes everything. Suddenly Danny is living in a home he’s never seen, with parents who miraculously survived the car crash that should have killed them. It’s like he’s a new Danny. But this alternate self has secrets—ties to an underground anarchist group that have already landed him in hot water. When he starts to develop feelings for Eevee, he’s even more disturbed to learn that he might have started the fire that ruined her work.

As Danny sifts through clues from his past and Eevee attempts to piece together her future, they uncover a secret that’s bigger than both of them. . . . And together, they must correct the breach between the worlds before it’s too late.

Amazon |

Indiebound |

Goodreads About the Author:

Amy K. Nichols is the author of YA science fiction novels

Now That You’re Here and

While You Were Gone, published by Knopf. She holds a master’s in literature and studied medieval paleography before switching her focus to writing fiction. Insatiably curious, Amy dabbles in art, studies karate, tries to understand quantum physics, and has a long list of things to do before she dies. She lives with her family outside Phoenix, AZ. In the evenings, she enjoys counting bats and naming stars. Sometimes she names the bats. Visit her online at

www.amyknichols.com.

Website |

Twitter |

Goodreads-- posted by Susan Sipal,

@HP4Writers

Where do you put the beats, those incidents that change the way the main character pursues his goal, in your novel?

http://www.adventuresinyapublishing.com/2015/04/finding-your-storys-beats-craft-of.html

by Jo Empson (Child’s Play, 2012)

Here’s a book that’s deceptively simple in text, in color, in motion.

An average rabbit, doing average rabbity things. White space, dark spot illustrations. Calm and steady.

But then. The page turn is the miraculous pacing tool for the picture book, and this one is a masterpiece. Swiftly, from the expected to the unexpected, from straightforward rabbityness to the unusual.

And the beautiful. And the wild and the wonderful.

Jo Empson’s art is a storyteller to follow. It unfolds visually, deftly, magically.

Desperately.

Because one day, Rabbit is gone. So is the color and the movement and the life.

“All that Rabbit had left was a hole.”

But, much like the art, Rabbit was a storyteller to follow.

And the color returns.

It’s a story about making a mark that leaves a legacy. It’s about telling a story and remembering one. It’s for anyone who is daring enough to leave drips of unrabbityness, and anyone brave enough to chase them.

I love insightful, meaty craft articles that help me both improve my knowledge of storytelling while also pushing me to analyze my current WIP. Today's Craft of Writing post comes from author Ara Grigorian, who expertly does both. And he does so with examples from two movies that I loved: Notting Hill and The Hunger Games. I know I'm going to be using his fabulous analysis to help with my upcoming revision! Hope you will too. And be sure to check out his upcoming release, Game of Love, which has been receiving glowing reviews, at the bottom of the post!

Finding Your Story’s Beats by Ara Grigorian

Stephen King has said time and again, if you want to be a better writer, you have to read a lot and write a lot. I will humbly add one more task to your to-do list. If you want to be a better storyteller, watch more movies.

Okay, okay, set down the pitchforks and torches. Yes, we all understand that movies are never as good as the books. And no, we're not trying to write a screenplay, we're trying to write better books. So what am I really talking about?

If you’re writing commercial fiction, where pacing, strong plot points, and increased tension in your selected genre matters, then our brothers and sisters who write scripts can teach us plenty.

This past February, I taught a workshop at the

Southern California Writers’ Conference in San Diego and again recently at a local high school in Los Angeles. The goal:

help you find your story’s key beats and their timing.

I’ve combined lessons from James Scott Bell (“Plot & Structure,” his workshops and his newly released “Super Structure”), Blake Snyder (“Save the Cat!” series) and John Truby (“The Anatomy of Story”). There are more. Pick your methodology, it doesn’t matter. They are all great and they all show that structure and story is king.

GAME OF LOVE is my debut novel (May 2015, Curiosity Quills Press). But before I got a publishing deal, and before my agent became

my agent, I realized something was missing. I’d get requests for fulls based on the query and first five pages, but something would fizzle.

This is what I did…

I selected nearly a dozen movies that were in my book’s genre, or had characters and situations that aligned well with my book. Why movies and not books? Simple: in ten hours I can watch five movies. In ten hours I can read a good chunk of one book. My goal was to learn, to dissect, and find the patterns, fast! Efficiency and effectiveness are critical to the author who also has a full-time job or other competing priorities.

After the third movie, the patterns emerged. By the tenth, I saw exactly what was missing from my book. I was missing key beats, and furthermore, those that I was hitting, I was hitting them late in the story line. Pacing and powerful, distinct scenes that propel the story forward – that was the secret to getting my book noticed.

First of all, what’s a beat? Per Wikipedia (the source of all truth), a beat is the timing and movement, referring to an event, decision, or discovery that alters the way the goal will be pursued by the protagonist. Key word is,

alter. It needs to be big, powerful.

In my workshop, to drive the point home of these key beats, we dissect movie clips. For this post we will analyze one of my favorite movies,

Notting Hill (NH) with Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant and a few scenes form

The Hunger Games. Spoiler Warning: I give away the ending!

Let’s jump in and analyze the most important scenes:

1.

Opening Image/Disturbance: The opening scene needs to set the mood, style, and stakes. This is also where we get to meet our main character(s) and their “before” world.

Notting Hill opens with a collage of clips where Julia is bombarded by the flash of cameras. A radio personality says she is the “biggest star” by far. The song, “She” plays in the background and if we’re listening to the lyrics we hear, “She may not be what she may seem.” We very quickly understand she’s incomplete. Immediately after we are introduced to Hugh’s character. An unsuccessful bookshop owner who was once married but is now alone, with hopes for romance.

In less than three minutes we get the world of these two characters. We also see that these characters can’t go on like this forever. It is unsustainable. Change, radical change is needed. How quickly have you set up your characters? Furthermore, how obvious are the stakes and the need for transformation?

2.

Theme stated: Blake Synder hammers this one. Early in the story (certainly before the 5% mark of your story) the theme will get stated in the form of an innocent question or statement. The main character will not get the significance, but this is the core of the story – the “What’s the story all about.” In the first couple of minutes in

Notting Hill, Hugh says “I always thought she was fabulous, but, you know, a million, million miles from the world I live in.” He’s not talking about the physical distance but the distance between an average guy and a superstar. The theme of this movie is can love overcome the crevasse that lies between a superstar and a nobody. All the challenges they face and all the fun scenes will test the theme.

Read through your manuscript, how quickly are you planting the seed for your reader? Are you then sprinkling the story with situations that revisit this theme?

3.

Catalyst/Inciting Incident/Trouble Brewing: This is where the main character’s world is thrown off balance – a life-changing moment. In

Notting Hill, Julia walks into Hugh’s store where they first meet (a small incident). Shortly after she leaves, he accidentally spills orange juice all over her (a bigger incident). She goes to his place to change (definitely merits a Facebook post!). Then to really throw his world into a tailspin, she kisses him. That is the catalyst moment. He is hooked.

Make sure your catalyst isn’t just a plot device but tied directly to the story and the theme.

4.

Break into Two/First Doorway of No Return: This is a powerful scene where the protagonist makes a definitive decision to pursue the journey, as crazy as it may seem. A decision that has no turning back. This is key because if the protagonist can say, “never mind” then it’s not a big enough pull to force the plot forward. The motivation has to be primal: love, fear, death, life, etc. and still tied to the theme. In

Notting Hill, he has fallen for her, badly. At first she’s pushes back but she also can’t help but be attracted to him – he’s different. Not like the celebrity types, so she decides to take a chance and goes on a date with him to his sister’s birthday party. In

Hunger Games, when Primrose is called for the reaping, Katniss makes an immediate decision – she will volunteer. Not because she thinks she can win, but because she needs to save her sister. Can Katniss change her mind? No way!

Do you have a scene that’s this big where your main character makes a decision that is profound and impossible to turn back from? What propels the call to adventure in your book?

5.

Mid-Point/Mirror Moment: This is a critical scene because this is where the dynamics of the story change. After the break into two, the scenes that follow are fun. They show us the promise of the premise. The main character lives in the upside down world of the choice that’s been made. In

Notting Hill, Hugh experiences the world of the celebrity while Julia lives in his simple world. But after all that fun stuff a key scene is needed that shows the bad guys are getting ready to ruin the party. Time clocks appear here. In

Notting Hill, Hugh discovers that she still has a boyfriend and in a beautifully shot scene on the streets of London, then on a bus, and finally in his bedroom we see it on his face -- he is taking inventory of the mess that is his life. In

Hunger Games, after all the training and the fun of the capital, the games begin. She’s on the platform, scared for her life.

What happens halfway in your story? Is there a moment where your main character is thinking, what have I done? Maybe even stares into the mirror wondering who is that person reflecting back at her?

6.

All is Lost/Dark Night of the Soul/Lights Out: A scene where the main character is now officially worse off than when the story first started. Feels like total defeat. In

Notting Hill, when he finds her again during a shoot, he overhears her with another actor. She dismisses him and says, “I don’t even know what he’s doing here.” He finally gets it and leaves. She then finds him and tries to explain why she said what she said, but he’s done. He can’t take the pain anymore. In a dramatic scene, she says, “And don’t forget, I’m also just a little girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her.” She leaves and Hugh is left stunned.

This is a critical scene because this is where humility will bring the main character to his knees. And from this humility a new idea will rise. The idea that will force the start of the final act.

7.

Break into Three/Second Doorway of No Return: A solution is found. The old world, the old way of being dies and a new world emerges. In

Notting Hill, he calls his friends to tell them what happened. Surrounded by his friends, he realizes that love is worth the pain of uncertainty. He realizes he needs her. And thus, they break into act three.

Your main character’s life is on the line (the alternative is death – professional, emotional, psychological). How big is your scene? Does the reason for the decision to go for it tie in with the theme?

8.

The Final Buildup and Battle: This is where you typically see the hero go up against the clock. He gathers the team, suits up for the challenge, executes the plan, only to be faced by another major challenge. But after digging deep finds a way to get to the final battle. Typically the main character will handle the bad guys in ascending order. In

Notting Hill, it’s a chase scene from one London Hotel to another until he finds her at her last press conference before she leaves the country. In a comedic scene he pretends he’s part of the press and asks, in front of all to hear, if she would consider staying if he admitted that he had been a “daft prick.” She does reconsider and a montage follows, to the music that opened the movie, we see footage from their wedding.

9.

The Final Scene/Resonance: But we’re not done because this is the bookend scene to the opening scene. We need to see the transformation of the character. We need to see that the world has also changed. In

Notting Hill, we started with two lonely people, trying to make it in their own lonely worlds. The movie ends with these two on a park bench, relaxing, he’s reading a book (a good man, clearly!), and she’s pregnant. Alone no more.

How does your story end? Is the final scene a bookend to the opening scene?

For this post, I highlighted nine story beats. You can easily identify 15, 30 or 40 if you invest a bit of time with the methodology of your choice and a day or two of back-to-back movies. I assure you, you will never watch a movie the same way again. And you will be a much more effective storyteller in the genre of your choice.

About the Author:

Ara Grigorian is a technology executive in the entertainment industry. He earned his Masters in Business Administration from University of Southern California where he specialized in marketing and entrepreneurship. True to the Hollywood life, Ara wrote for a children's television pilot that could have made him rich (but didn't) and nearly sold a video game to a major publisher (who closed shop days later). Fascinated by the human species, Ara writes about choices, relationships, and second chances. Always a sucker for a hopeful ending, he writes contemporary romance stories targeted to adult and new adult readers.

He is an alumnus of both the Santa Barbara Writers Conference and Southern California Writers' Conference (where he also serves as a workshop leader). Ara is an active member of the Romance Writers of America and its Los Angeles chapter.

Ara is represented by Stacey Donaghy of Donaghy Literary Agency.

Twitter |

Website |

Facebook |

Goodreads About The Book:

Game of Love is set in the high-stakes world of professional tennis where fortune and fame can be decided by a single point.

Gemma Lennon has spent nearly all of her 21 years focused on one thing: Winning a Grand Slam. After a disastrous and very public scandal and subsequent loss at the Australian Open, Gemma is now laser-focused on winning the French Open. Nothing and no one will derail her shot at winning - until a heated chance encounter with brilliant and sexy Andre Reyes threatens to throw her off her game.

Breaking her own rules, Gemma begins a whirlwind romance with Andre who shows her that love and a life off the court might be the real prize. With him, she learns to trust and love… at precisely the worst time in her career. The pressure from her home country, fans, and even the Prime Minister to be the first British woman to win in nearly four decades weighs heavily.

As Wimbledon begins, fabricated and sensationalized news about them spreads, fueling the paparazzi, and hurting her performance. Now, she must reconsider everything, because in the high-stakes game of love, anyone can be the enemy within… even lovers and even friends.

In the

Game of Love, winner takes all.

Amazon US |

Amazon UK |

Barnes & Noble |

Goodreads-- posted by Susan Sipal,

@HP4Writers

Join Leslie Helakoski and Darcy Pattison in Honesdale PA for a spring workshop, April 23-26, 2015. Full info

here.

COMMENTS FROM THE 2014 WORKSHOP:

- "This conference was great! A perfect mix of learning and practicing our craft."�Peggy Campbell-Rush, 2014 attendee, Washington, NJ

- "Darcy and Leslie were extremely accessible for advice, critique and casual conversation."�Perri Hogan, 2014 attendee, Syracuse,NY

Tension on every page is the mantra for fiction writers. But what if your tension is spread unevenly throughout the story? That may be fine, because stories need a natural rhythm, an ebb and flow of action, thoughts, dialogue and reflection (inner dialogue). Some scenes may be crammed with small actions, while others pace steadily through the setting. Sometimes, though, I find that I’ve packed a scene with too many MAJOR revelations or actions, creating a top-heavy scene; that scene is usually matched by another scene that lacks enough tension.

My current WIP was in that position this week. One scene had two major confrontations. So, I decided to see if I could lift one Major Complication and put it elsewhere. The actual text, a revelation that someone was searching for the main character, took about 20 lines of text. Not so bad to move elsewhere, I thought.

But every part of a story is intertwined with every other part.

Timeline. First, there’s timeline issues. EventA happens before EventB. The RevelationEvent was originally the EventA, but I moved it to an EventC position, which meant that I had to go back and clean up the time line. There could be no mention of the RevelationEvent before Event B, of course. This is tedious work. You have to reread chapters thinking about what a reader should know at this point in the story, and make sure there’s no hint of the RevelationEvent that will spoil the surprise. Of course, I can hint at it; that’s called foreshadowing. Foreshadowing’s role, though, is to make the reader slap his/her forehead and say, “Duh! That’s exactly what should happen. Why didn’t I see it coming?” The reader should still be surprised, but the surprise is believable. Cleaning up the timeline is hard work, and if you slip up with even one half-sentence, you’ll be nailed on it by some alert reader.

Fitting it in. Unfortunately, you can’t just pick up the 20 lines and insert them where Event C occurs. Much of it may be salvaged verbatim, but much of it needs to be worded differently at the new place of the story. Keep the core of it, the meaning, but be willing to rewrite to make it seamless. The goal is to make it seem that the story was originally written this way.

As a revision exercise, I required my freshman composition students to write eight different openings for their essay. Often, the third or fifth or eighth opening was dynamite, and the writer chose to start his/her essay with it. Too often, though, it was stuck on the front and had no relationship to the rest of the story. I modified the assignment: students still wrote the eight openings. But then, in class to make sure they did it, they had to start writing the essay again from that starting point and keep writing for a timed period. I made sure the writing time was long enough to carry them into the body of the essay. That resulted in strong openings that were integrated into the whole essay. That’s what you want here, too.

One caution: keep a copy of the original version, because you may not like moving the event to a new place. In Scrivener, take a snapshot. In word processors, make a backup copy or a versioned copy; or use track changes to make the preliminary changes and then decide if you want to make them permanent.

The strategy of moving events is easy on the imagination. I don’t have to think up new events or complications; instead, I just need to use what I’ve already written in a stronger way.

Hi, folks! I am an artistic person, and I buzz around art. I will dip my toe into most forms of expression. There are a few that I've focused on and have found that those experiences have informed my novel craft. This week I'm going to talk about screenplay lessons.

I've written a few screenplays. This experience has helped me with novel craft. A screenplay is a working document, it is not the finished product: the film. I've learned about writing novels by writing screenplays. Here are three useful bits that I've learned:

First, screenplays force you to think about scenes and pacing. A screenplay has a tight structure. It is much more compact than a novel and rarely has any room for internal thoughts. Becoming more aware of scenes has made me more aware of what to cut in my novels. Every scene in my novel must argue for its right to be there. Novelists tend to be in love with the beauty of the words, and sometimes that is at the expense of storytelling. Each scene in my novel must move the plot forward, develop the journey of the main character, offer serious conflict, offer a glimpse of the internal working of the main character, have laser focus on the goal of the story, and offer some beautiful language and deep internal thought. If I can't achieve this with a scene, I toss it on reject pile.

Second, screenplays can help you move forward when you are stuck. Like picture books, screenplays are a visual medium. Sometimes, I reach a place in the novel that I'm not sure how to proceed forward. I break open Final Draft or Celtx and move forward with my novel in a screenplay format. My first drafts are now always a mix of screenplay sections and narrative. Writing a screenplay is analogous to sketching. A rough draft is a sketch of the novel. All the needed scene pieces are broken apart: opening with setting, dividing the dialogue, dropping in an emotional tag, and then describing the action can keeps me from bogging down in a first draft. Next time your draft grinds to a halt, try writing the next scene in screenplay format.

Finally, screenplays can help you beat the static parts out of your novel. Screenplays do not welcome big chunks of dialogue, must keep action swirling on screen to entice the film goer, and must be aware that the person who plays the character in the screenplay is paramount in making that character come to life. I avoid prosy dialogue. Screenplays have made me aware of this. No one wants to read about nothing happening. It's surprising how easy it is to write about a character watching the sunrise or swimming in the lake, or reading a book. Blow up that sun, fill that lake with piranhas, and have the heroine toss that book into that arrogant so-n-so's face. Also characters must be nuanced. I really cast my characters now when I write. I learned this from screenplays. Character on a great journey is still a working document, the character in the screenplay vs the character in a film. It's the little things that set characters apart and make them spring from the page. You have to know if your character loves chocolate, scream when she is angry, or bite her fingernails.

Novels need to breath with life. Screenplays have helped me achieve that.

Hope something here is helpful. :) I will be back next week with more novel crafty lessons.

Here is a doodle: Clown

Finally a quote for your pocket:

When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art.’ I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. George Orwell

Hi folks, a brand new shiny year! Love it! I hope that you are making goals and opening up to new possibilities. Fold up all those disappointments and failures. Take anything you learned from these experiences and move on. Look forward. Huzzah!

In January, I always explore one of my great passions and that is novel craft. I'm a novelist at heart. My first published book was PLUMB CRAZY. It was out from Swoon Romance in June 2014, but is going away soon. Cancellation--just like so many fantastic TV shows that get cancelled (cough, Firefly), so goes my book. C'est la vie.

Don't despair, you who hunger for a paperback of PLUMB CRAZY to hold. I am going to self-publish the book for anyone who is interested. It's going to take a little time to put that together, but the book should be ready to be a summer read again. :) Thanks to all the people who have supported this first novel publishing effort of mine! Galaxies of stories are ahead!

Anyway, onto to novel craft. I am an extremely visual person. I see three dimensional landscapes in my head. I also write in many genres and find that the skills I use in one genre inform me as I approach a different genre. These skills serve me well. Writing picture books helps me write novels.

When I write a picture book, I write the text and then I write what is going on in the picture. From an absolute telling perspective, I write what is going on in the scene before I actually write the text for the picture book. I do this for every page. It turned out that this is an effective technique to write novel scenes, especially ones I'm stuck on. I just tell what is going down in the scene in a fat paragraph. When I'm finished I write the scene with that word picture I created in the back of my mind. Writing the scene rolls out a lot more smoothly.

Picture book structure helps me plan the structure of my novels. Picture books have the same beats as a novel but they come much faster. I make sure that my novel has clear beats that echo picture book structure. What is a beat? Plot points, turning points, plot twists. If you are having a tough time figuring out if your novel has a decent story arc. Study a few picture books. What launches the action? How does the mc react? What happens at the midpoint? How does the action rise? What is the climax? How long does it take the story to resolve? All these questions and a picture book in hand should send you on your way while writing a novel.

Well, there is a tea cup of usefulness for your creative journey. I hope you come back next week for more Novel Craft.

Here is a doodle. :) PINK

Robert F. Kennedy

Before we get to the nitty-gritty, let me give a hearty shout out to all of you doing NaNoWriMo. *POM-POMS* I’ve never been able to NaNo with the rest of the world, since November is such a crazy month for me, but I have so much respect for all of you in the trenches right now. KEEP IT UP! You’re halfway there!

Kenny Louie @ Creative Commons

So, I mentioned that November is insane, right? My son’s birthday falls just before Thanksgiving. This year, we’re throwing his first party. He wanted a Darth Vader theme, and I may have gone a teensy bit overboard. Regardless, his birthday party, combined with his actual birthday, followed by my father-in-law’s birthday, and then Thanksgiving for the family at MY HOUSE THIS YEAR… Well. Let’s just say that it’s all about planning and pacing right now.

Advice that is so often true of writing, too.

And I just happen to have this nifty post on the subject, which originally aired at Lisa Hall-Wilson’s excellent blog. So, in homage to the difficult topic of pacing, and in an effort to maintain my natural hair color through yet another November, here it is, for your viewing pleasure…

I’d like to start this post by stating an opinion that I think pretty much everyone shares: Pacing Sucks. When you get it right, no one really notices. I mean, how many times have you read a 5-star review that went on and on about the awesome pacing? On the other hand, when the pacing’s off, it’s obvious, but not always easy to pinpoint; you’re just left with this vague, ghostly feeling of dissatisfaction. One thing, though, is certain: if the pacing is wrong, it’s definitely going to bother your readers, so I thought I’d share some tips on how to keep the pace smooth and balanced.

1. Current Story vs. Backstory. Every character and every story has backstory. But the relaying of this information almost always slows the pace because it pulls the reader out of the current story and plops them into another one. It’s disorienting. And yet, a certain amount of backstory is necessary to create depth in regards to characters and plot. To keep the pace moving, only share what’s necessary for the reader to know at that moment. Dole out the history in small pieces within the context of the current story, and avoid narrative stretches that interrupt what’s going on. Here’s a great example from Above , by Leah Bobet:

, by Leah Bobet:

The only good thing about my Curse is that I can still Pass. And that’s half enough to keep me out of trouble. But tonight it’s not the half I need because here’s Atticus, spindly crab arms folded ‘cross his chest, waiting outside my door. His eyes glow dim-shot amber—not bright, so he’s not mad, just annoyed and looking to be mad.

Bobet could have taken a lengthy paragraph to explain that certain people in this world have curses that are really mutations, that Atticus has crab claws for hands and his eyes glow when he gets angry. But that would’ve slowed the pace and been boring. Instead, Bobet wove this information into the current story—showed Atticus leaning against the door, showed his crustacean claws and his freaky, glowing eyes so the reader knows that he’s a mutant and, to the narrator, at least, this is normal. This is an excellent example of the artful weaving of backstory into the present story.

2. Action vs. Exposition/Internal Dialogue. Action is an accelerant. It keeps the pace from dragging. Granted, there will be places in your story that are inherently passive, where characters have to talk, or someone needs to think things out. The key is to break up these places with movement or activity. Characters should be in motion—smacking gum or doodling or fidgeting— while talking. Give them something to do during their thoughtful moments, whether it’s peeling carrots or painting a picture. These bits of action are like an optical illusion, fooling the reader into thinking something’s happening, when really, nothing’s going on. This is one scenario when readers actually prefer to be fooled, so make sure to energize those narrative stretches with action.

Oliver Kendal @ Creative Commons

3. Conflict vs. Downtime. On the flip side, you can’t have a story that’s all go and no stop. One might think that since action is good, more action is better. Not true. Readers need time to catch their breath, to recover from highly emotional or stressful scenes. A good pace is one that ebbs and flows—high action, a bit of recovery, then back to the activity again. Even The Maze Runner, possibly the most active novel I’ve ever read, has its moments of calm. When it comes to conflict and downtime, a definite balance is needed for the reader to feel satisfied.

4. Keep Upping the Stakes. We know that conflict is important—so important that every single scene needs it. But for conflict to be effective, it needs to escalate over the course of the story. To keep the reader engaged, each of the major conflict points needs to be bigger, more dramatic, and with stakes that are more desperate. One of my favorite reads of 2013 was Ruta Sepetys’ Between Shades of Gray , a historical fiction novel about the deportation of a Lithuanian family during World War II. It starts out ominous enough, with the family being forced from their home. Over the course of the story, they’re moved by cattle car across the continent, relocated to a forced labor camp, and eventually reach their final destination—a camp in the Arctic Circle where they’re expected to survive the elements with whatever resources they can scrounge. Clearly, lots of other conflict is interspersed, but when it comes to the major points, each one should have greater impact than the last.

, a historical fiction novel about the deportation of a Lithuanian family during World War II. It starts out ominous enough, with the family being forced from their home. Over the course of the story, they’re moved by cattle car across the continent, relocated to a forced labor camp, and eventually reach their final destination—a camp in the Arctic Circle where they’re expected to survive the elements with whatever resources they can scrounge. Clearly, lots of other conflict is interspersed, but when it comes to the major points, each one should have greater impact than the last.

5. Condense the timeline. When possible, keep your timeline tight. If it gets too spread out, the story will inevitably drag. It’s also hard, in a story that covers a long span, to keep things smooth; there will be time jumps of weeks or months or even years between scenes. Too many of these give the story a jerky feel. So when it comes to the timeline, condense it as much as possible to keep the pace steady.

For sure, pacing is tricky, but I’ve found these nuggets to be helpful in maintaining a good balance. What other tips do you have for keeping your story moving at the right pace?

The post Pacing Tips appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

.jpeg?picon=2691)

By: LAURIE WALLMARK,

on 10/28/2014

Blog:

Just the Facts, Ma'am

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

pacing,

Add a tag

By: Carter Higgins,

on 9/30/2014

Blog:

Design of the Picture Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

candlewick press,

balance,

pacing,

negative space,

perspective,

line,

layout,

jon klassen,

mac barnett,

sam and dave dig a hole,

design,

Add a tag

by Mac Barnett and Jon Klassen (Candlewick Press, 2014)

You know Mac and Jon. You love Mac and Jon. Now meet Sam and Dave. You’ll love Sam and Dave.

Don’t rush into the pages just yet. This is one of the best covers I’ve seen in a long while. If we weren’t so aware that Jon Klassen (that insta-recognizable style!) is a contemporary illustrator, I would wholeheartedly presume that it was some vintage thing in a used bookstore. A find to gloat about, a find that makes you wonder just how you got so lucky.

The hole. The space left over. The words, stacked deeper and deeper. The apple tree whose tippy top is hidden. Two chaps, two caps, two shovels. One understanding dog.

Speaking of two chaps, two caps, and two shovels, check out the trailer.

(I’ll wait if you need to watch that about five more times.)

The start of their hole is shallow, and they are proud. But they have only just started. Sam asks Dave when they should stop, and this is Dave’s reply:

“We won’t stop digging until we find something spectacular.”

Dave’s voice of reason is so comforting to any young adventurer. It’s validating that your goal is something spectacular. (Do we forget this as grownups? To search for somthing spectacular? I think we do.)

Perhaps the pooch is the true voice of reason here, though he doesn’t ever let out a bark or a grumble. Those eyes, the scent, the hunt. He knows.

(click to enlarge)

And this is where Sam and Dave Dig a Hole treads the waters of picture book perfection. The treasure, this spectacular something, is just beyond the Sam and Dave’s reality. The reader gets the treat where Sam and Dave are stumped. Do you want to sit back and sigh about their unfortunate luck? Do you want to holler at them to just go this way or that way or pay attention to your brilliant dog? Do you root for them? Do you keep your secret?

The text placement on each page is sublime. If Sam and Dave plant themselves at the bottom of the page, so does the text. If the hole is deep and skinny, the text block mirrors its length. This design choice is a spectacular something. It’s subtle. It’s meaningful. It’s thoughtful and inevitable all at once.

(click to enlarge)

And then – then! Something spectacular. The text switches sides. The boys fall down. Through? Into? Under? Did the boys reach the other side? Are they where they started? Is this real life? Their homecoming is the same, but different. Where there was a this, now there is a that. Where there was a hmm, now there is an ahhh.

Spectacular indeed.

I like to think that the impossible journey here is a nod to Ruth Krauss and Maurice Sendak’s collaboration, A Hole is to Dig. That’s what holes are for. That’s what the dirt asks of you. It’s not something you do alone or without a plan or without hope. Sam and Dave operate in this truth. They need to dig. There’s not another choice.

(image here // a first edition, first printing!)

Sidenote: I’m pretty thrilled that these scribbles live in my ARC.

Look for this one on October 14th.

SAM AND DAVE DIG A HOLE. Text copyright © 2014 by Mac Barnett. Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Jon Klassen.Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

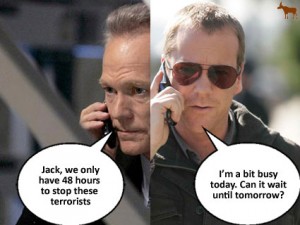

We all want to write an engaging, page-turning story. But that’s harder said than done, as is proven by the number of times I leave a movie complaining that it was one long bull crap moment. There are tips and tricks to successfully writing a can’t-put-it-down book. Eileen Goudge is here today to share some of them with us…

Courtesy: Sam Beckwith at CC

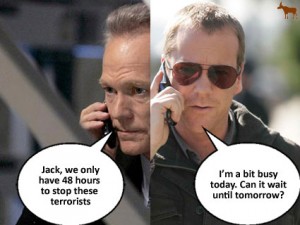

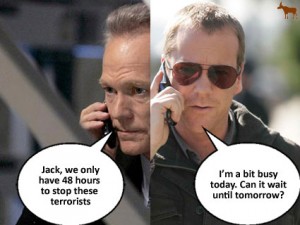

If you’ve watched the hit TV show “24”, you know that every day in the life of hero Jack Bauer is a really, really bad day. When he’s not hunting terrorists he’s saving a major city from total annihilation. Is any of it remotely believable? Hell no. But we watch anyway. Why? Because the action moves at such a rapid clip, we don’t pause to reflect on the gaping plot holes until the credits are rolling. (Seriously, a middle-aged guy singlehandedly taking out a dozen armed terrorists?)

It’s the same reason authors like Stephen King have legions of fans. King is a master of plot and pacing. He knows that to create a novel that’s addictive you have to “kick it up a notch,” in the words of chef Emeril Lagasse. King’s current bestseller, Mr. Mercedes, had me at page one. It was off and running when I still had one foot on the ground climbing into the passenger seat. (It contains some Jack Bauer-like heroics, is all I can say without being a spoiler.) Is it the kind of stuff that would ever happen in real life? Doubtful. But who cares? We get enough real life in our own lives, and it’s usually pretty tame compared to a day in the life of Jack Bauer. Whether it’s a novel or filmed entertainment, fantasy or reality-based, we all want the same thing when reading a book: to be swept away.

So how do you accomplish this when you’re writing a novel? How do you take a low-octane plot and kick it up at notch?

Don’t be afraid to be over the top. Your plot doesn’t have to be in the realm of the probable, just believable enough to keep readers from rolling their eyes in disbelief. The only rule is that it has to make sense in the context of the story so it doesn’t seem out of character.

When I first started out as a writer I made it a practice to keep up with what was selling by reading at least one book by each of the authors whose titles frequently appeared on the New York Times bestseller list. If you want to understand the perennial popularity of a Danielle Steel, check out Palomino. The heroine is not only dumped by her cheating husband, an anchor on the local news channel, she then has the torment of watching him and his now-pregnant girlfriend/co-anchor on TV every day. And that’s just the first chapter. Before she’s paralyzed in an accident.

You may roll your eyes at this plot line, but in the hands of a skilled writer like Steel, it’ll have you turning the pages too fast to think, “Please. Like this would ever happen!”

In my first novel, Garden of Lies, which was a New York Times bestseller, my doctor heroine is faced with an unwanted pregnancy as a first-year intern. She agrees to end the pregnancy only if her doctor boyfriend will perform the abortion. She wants him to know it’s a big deal, not the minor procedure he seems to think it is. In ending a life they’re both scarred for life. And that’s just one of the subplots. The main plot is the classic tale of babies switched at birth with a twist: It’s the mother of one of the babies who consciously makes the switch.

Create high stakes. It’s one thing to have the protagonist lose his job or have the bank foreclose on his house. We read about this sort of thing every day in the news, so it doesn’t seem out of the ordinary; we feel for the person crying on TV because they lost their house and wish him or her well. With fiction, we want the exact opposite: more pain and suffering. If the protagonist is thrown into hot water, we want that water to be scalding.

Take The Firm, for instance—the novel that launched the mega-bestselling John Grisham’s career. The protagonist, Mitch, not only suspects there’s something fishy going on at the law firm that’s just hired him, but he notices the mortality rate among junior partners is unusually high. Soon he’s on the hit list and being chased, not only by the crooks, but by the mob and FBI. Who cares if that’d likely never happen in real life and you wouldn’t survive to tell the tale if it did? It makes for a compulsively readable novel and was made into a film that was a box-office hit.

Make us care before you toss your hero into hot water. There’s a reason you don’t see a dead body in the opening pages of my newest title, Bones and Roses (Book One of my Cypress Bay mystery series). I wanted readers to first get to know my amateur sleuth Tish—a recovering alcoholic who lost her mom at a young age—so when the corpse does turn up, they’d understand and appreciate the impact it has on her.

In opening scenes, suspense should come from the protagonist himself (or protagonists if it’s a multiple-viewpoint novel). Readers will want to know more about this character, so they’ll keep turning the pages to find out what happens next. If the author fails to create reader sympathy for the protagonist before he or she is put in a tight spot or a tight spot becomes even tighter, the reader won’t care whether or not he or she finds a way out.

Take The Shining, by Stephen King. King foreshadows the horrors to come in an opening scene in which down-on-his-luck protagonist Jack Torrance is interviewing for the job of caretaker of the Overlook Hotel. You care what happens to Jack and his wife and son, and you suspect it’s not going to turn out all hunky-dory when he gets the job.

In short, if you haven’t developed reader sympathy for your protagonist, the sledgehammer blow on which the plot hinges won’t have as much impact.

Keep up the pace. Remember when you were a kid and your big brother would twist your arm behind your back until you cried “uncle”? There’s no crying uncle in a taut, fast-paced novel. As you build toward the climax, it needs to be fast and furious with no letting up. In Michael Kortya’s masterful suspense novel, Those Who Wish Me Dead, a wilderness guide is leading a group of at-risk youths—among them, a kid who witnessed a murder and is being hunted by killers. Throw in a former U.S. marshal who has her own reasons for finding the kid, a forest ranger with a tortured past, the hero’s plucky wife back at the ranch, and a couple of really scary psychopaths, and you have a potent blend that’ll get the reader’s pulse pounding like a triple shot of espresso.

You write romance? Same rule applies as with horror and suspense novels: keep those pages turning with memorable characters and a compelling plot. Will Scarlett find happiness with Rhett? Will Bridget Jones get over herself and get with Mr. Darcy? These questions keep the plot bubbling and the protagonist stewing to perfect, delicious done-ness.

These are just a few of the basics. For more about how to write a page-turner, I recommend Writing the Blockbuster Novel, an excellent how-to written by my former literary agent and ex-husband, Albert Zuckerman. As someone who’s published a novel of his own and shaped countless others (including those of bestselling author Ken Follett), Al really knows his stuff.

New York Times’ bestselling novelist Eileen Goudge wrote her first mystery, “Secret of the Mossy Cave,” at the age of eleven. She went on to pen the perennially popular GARDEN OF LIES—which was published in 22 languages around the world—and numerous other women’s fiction titles. BONES AND ROSES is the first book in her Cypress Bay Mysteries series. She lives in New York City with her husband, television film critic and entertainment reporter Sandy Kenyon. Online, you can find her at her website.

New York Times’ bestselling novelist Eileen Goudge wrote her first mystery, “Secret of the Mossy Cave,” at the age of eleven. She went on to pen the perennially popular GARDEN OF LIES—which was published in 22 languages around the world—and numerous other women’s fiction titles. BONES AND ROSES is the first book in her Cypress Bay Mysteries series. She lives in New York City with her husband, television film critic and entertainment reporter Sandy Kenyon. Online, you can find her at her website.

The post Kick it up a Notch: Top Tips on Writing a Page-Turning Novel appeared first on WRITERS HELPING WRITERS.

We all want to write an engaging, page-turning story. But that’s harder said than done, as is proven by the number of times I leave a movie complaining that it was one long bull crap moment. There are tips and tricks to successfully writing a can’t-put-it-down book. Eileen Goudge is here today to share some of them with us…

Courtesy: Sam Beckwith at CC

If you’ve watched the hit TV show “24”, you know that every day in the life of hero Jack Bauer is a really, really bad day. When he’s not hunting terrorists he’s saving a major city from total annihilation. Is any of it remotely believable? Hell no. But we watch anyway. Why? Because the action moves at such a rapid clip, we don’t pause to reflect on the gaping plot holes until the credits are rolling. (Seriously, a middle-aged guy singlehandedly taking out a dozen armed terrorists?)

It’s the same reason authors like Stephen King have legions of fans. King is a master of plot and pacing. He knows that to create a novel that’s addictive you have to “kick it up a notch,” in the words of chef Emeril Lagasse. King’s current bestseller, Mr. Mercedes, had me at page one. It was off and running when I still had one foot on the ground climbing into the passenger seat. (It contains some Jack Bauer-like heroics, is all I can say without being a spoiler.) Is it the kind of stuff that would ever happen in real life? Doubtful. But who cares? We get enough real life in our own lives, and it’s usually pretty tame compared to a day in the life of Jack Bauer. Whether it’s a novel or filmed entertainment, fantasy or reality-based, we all want the same thing when reading a book: to be swept away.

So how do you accomplish this when you’re writing a novel? How do you take a low-octane plot and kick it up at notch?

Don’t be afraid to be over the top. Your plot doesn’t have to be in the realm of the probable, just believable enough to keep readers from rolling their eyes in disbelief. The only rule is that it has to make sense in the context of the story so it doesn’t seem out of character.

When I first started out as a writer I made it a practice to keep up with what was selling by reading at least one book by each of the authors whose titles frequently appeared on the New York Times bestseller list. If you want to understand the perennial popularity of a Danielle Steel, check out Palomino. The heroine is not only dumped by her cheating husband, an anchor on the local news channel, she then has the torment of watching him and his now-pregnant girlfriend/co-anchor on TV every day. And that’s just the first chapter. Before she’s paralyzed in an accident.

You may roll your eyes at this plot line, but in the hands of a skilled writer like Steel, it’ll have you turning the pages too fast to think, “Please. Like this would ever happen!”

In my first novel, Garden of Lies, which was a New York Times bestseller, my doctor heroine is faced with an unwanted pregnancy as a first-year intern. She agrees to end the pregnancy only if her doctor boyfriend will perform the abortion. She wants him to know it’s a big deal, not the minor procedure he seems to think it is. In ending a life they’re both scarred for life. And that’s just one of the subplots. The main plot is the classic tale of babies switched at birth with a twist: It’s the mother of one of the babies who consciously makes the switch.

Create high stakes. It’s one thing to have the protagonist lose his job or have the bank foreclose on his house. We read about this sort of thing every day in the news, so it doesn’t seem out of the ordinary; we feel for the person crying on TV because they lost their house and wish him or her well. With fiction, we want the exact opposite: more pain and suffering. If the protagonist is thrown into hot water, we want that water to be scalding.

Take The Firm, for instance—the novel that launched the mega-bestselling John Grisham’s career. The protagonist, Mitch, not only suspects there’s something fishy going on at the law firm that’s just hired him, but he notices the mortality rate among junior partners is unusually high. Soon he’s on the hit list and being chased, not only by the crooks, but by the mob and FBI. Who cares if that’d likely never happen in real life and you wouldn’t survive to tell the tale if it did? It makes for a compulsively readable novel and was made into a film that was a box-office hit.

Make us care before you toss your hero into hot water. There’s a reason you don’t see a dead body in the opening pages of my newest title, Bones and Roses (Book One of my Cypress Bay mystery series). I wanted readers to first get to know my amateur sleuth Tish—a recovering alcoholic who lost her mom at a young age—so when the corpse does turn up, they’d understand and appreciate the impact it has on her.

In opening scenes, suspense should come from the protagonist himself (or protagonists if it’s a multiple-viewpoint novel). Readers will want to know more about this character, so they’ll keep turning the pages to find out what happens next. If the author fails to create reader sympathy for the protagonist before he or she is put in a tight spot or a tight spot becomes even tighter, the reader won’t care whether or not he or she finds a way out.

Take The Shining, by Stephen King. King foreshadows the horrors to come in an opening scene in which down-on-his-luck protagonist Jack Torrance is interviewing for the job of caretaker of the Overlook Hotel. You care what happens to Jack and his wife and son, and you suspect it’s not going to turn out all hunky-dory when he gets the job.

In short, if you haven’t developed reader sympathy for your protagonist, the sledgehammer blow on which the plot hinges won’t have as much impact.