new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Friends of the Arts, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 36

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Friends of the Arts in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Taylor Coe,

on 3/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

The Ed Sullivan Show,

Ron Rodman,

Jack Paar,

paar,

the Jack Paar program,

entrepreneur—nbc’s,

British Invasion,

*Featured,

TV & Film,

Arts & Leisure,

American television,

February 1964,

sullivan,

Books,

Music,

Beatles,

Ed Sullivan,

beatlemania,

Add a tag

By Ron Rodman

Sunday, 9 February 2014 marked the 50th anniversary of the American television broadcast of the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show. For many writers on pop music, the appearance on the Sullivan show not only marked the debut of the Beatles in the United States, but also launched their career as international pop music superstars. The mass exposure to millions of television viewers rocketed the Fab Four to national prominence in the United States, and created a chain reaction for stardom in the entire world.

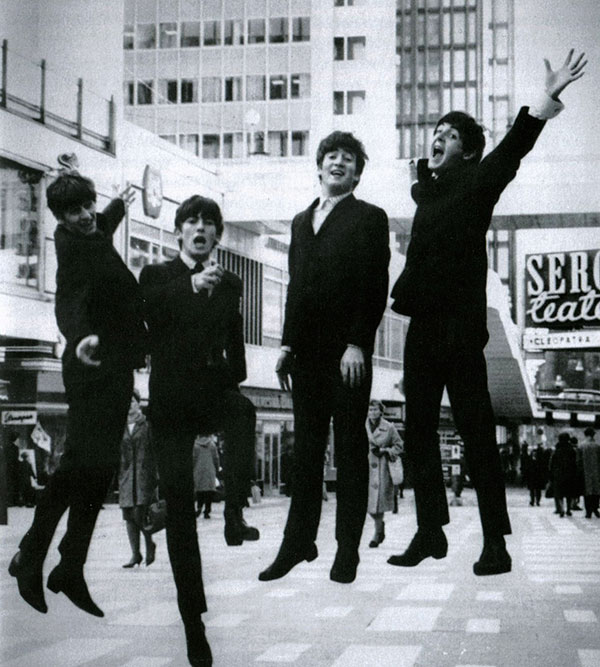

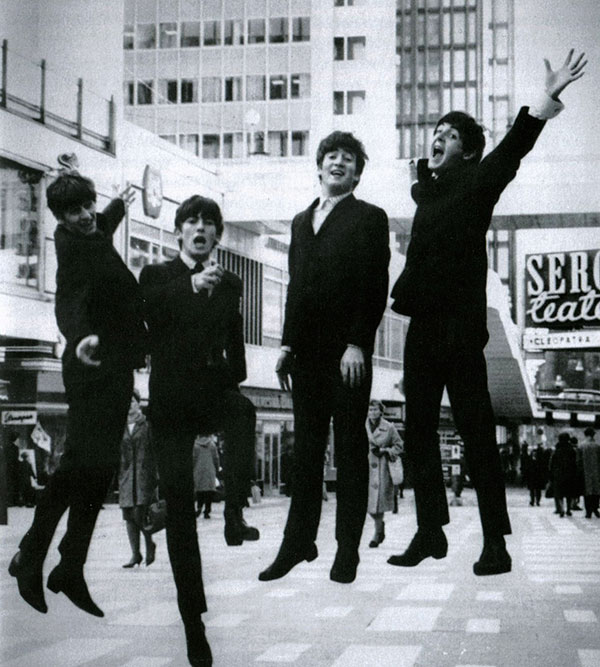

The Beatles, Stockholm, 1963

While the charisma and quality of the Beatles’ music drew great popularity in 1964, the group’s success was assisted by the entrepreneurial skills of American television, notably by the expertise of Ed Sullivan. However, several other television broadcasts predated the Sullivan show appearance, and laid the groundwork for the Beatles’ stardom in the United States. In particular, two news stories about the Beatles were aired in November 1963, four full months before the Sullivan appearance. This, plus another taped appearance by the group by another entrepreneur, NBC’s Jack Paar, paved the way for the Beatles’ stardom in the United States.

The Ed Sullivan Show

Ed Sullivan began his career as a journalist throughout the 1920s and worked his way into the position as theater columnist for the New York Daily News when Walter Winchell left the paper in the early 1930s. Sullivan was also a host for Vaudeville theaters, serving as master of ceremonies for a number of shows during World War II. He broke into television as host of telecasts of New York’s Harvest Moon Ball on CBS, and was asked to host a weekly variety show called Toast of the Town in 1948. The show would be renamed The Ed Sullivan Show in 1955.

With his journalistic experience, Sullivan was able to use his contacts to attract a wide range of celebrities on the show. He attracted comedians such as Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Broadway stars like Julie Andrews, jazz greats like Dizzy Gillespie and Ella Fitzgerald, and even opera singers like Maria Callas and Robert Merrill. However, Sullivan may be best known for bringing rock‘n’roll to the small screen. He had Elvis Presley on the show on 6 January 1957, and many rockers such as Buddy Holly, Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, and many others thereafter.

Sullivan’s embrace (or at least tolerance) for rock music paved the way for the Beatles. Sullivan reportedly heard (or heard of) the Beatles during a trip to London and decided to put them on his show. He offered the band $10,000 to appear, a figure that, adjusted for inflation, would be a somewhat modest $75,000 in today’s dollars.

As the show opened on that historic night in 1964, Sullivan reported that Elvis Presley and his manager, Colonel Tom Parker, had sent a telegram to the Beatles wishing them luck. In his introduction, Sullivan also used the increased viewership to plug some of his other acts on previous shows, notably Topo Gigio (the Italian/Spanish mouse puppet created by Maria Perego), Van Heflin, Ella Fitzgerald, and Sammy Davis, Jr. But the tension to hear the Beatles was palpable, and he segued into a commercial quickly, promising the Beatles after the break.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The appearance by the Beatles almost didn’t happen. George Harrison reportedly had a sore throat the week before, but by broadcast, was better. So, the Beatles went live with their full line-up, performing five songs that night: “All My Loving,” “Till There Was You,” “She Loves You,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

News stories

While the Ed Sullivan appearance marked the first live US TV appearance of the Beatles, the groundwork had already been laid to introduce the band to the United States a few months earlier. NBC News did a four-minute story on the Beatles that was broadcast on The Huntley-Brinkley Report on 16 November 1963, three full months before the Sullivan show. The feature was narrated by reporter Edwin Newman, who would later anchor the NBC News.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Not to be “scooped” by NBC, CBS News also produced a five-minute piece on the Fab Four, which aired on 21 November, the eve of the fateful day on which President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Alexander Kendrick, CBS’s London Bureau Chief taped the story, which showed footage of the Beatles performing in England, and the story ended with Kendrick ruminating on the social significance of the group, representing England’s youth, or at least England’s youth as they “wanted to be.”

The Jack Paar Program

Also predating the Sullivan Show, the first prime time film footage of the Beatles actually aired on 3 January 1964. The person responsible was another entrepreneur—NBC’s Jack Paar. Like Ed Sullivan, Paar was not a TV celebrity “natural” and came to television as a master of ceremonies. After World War II, Paar made some appearances in a few low-budget films, and made his way to television as a game show host. He was chosen as the regular replacement for Steve Allen as the host of NBC’s Tonight Show in 1957. Paar did not have Allen’s musical talent, nor his talent for sketch comedy or practical jokes, but was able to surround himself with unusual talent to market his show. While not as “wooden” on stage as Sullivan, Paar tended to be low-key and conversational, rather than charismatic and presentational. Like Sullivan, Paar also had a flair for discovering unique talent and is often credited for discovering, or at least popularizing, such off-beat characters as comedians Jonathan Winters, Bill Cosby, and Bob Newhart. Paar left the Tonight Show (ushering in the Johnny Carson era) in 1962, but went on to host a weekly variety show called The Jack Paar Program, that aired on Friday nights on NBC. It was on this program that he introduced the Beatles to the United States.

Like Sullivan, Paar had heard of the Beatles while in London and decided to show some film footage of the band as a joke. “I thought it was funny,” he quipped later on a television retrospective. He admitted that he had no idea that the band would change the course of music history. On the 1963 broadcast, after showing the footage, he quipped: “Nice to know that England has risen to our [American] cultural level.”

The episode with the footage was taped on 16 November 1963, the same date as the NBC news story (undoubtedly the story was fed to Paar from the network news bureau), but was not aired until 3 January 1964, undoubtedly delayed by the Kennedy assassination. Paar’s film clip still predates the Sullivan appearance by more than a month.

Would the Beatles have made it as superstars without the entrepreneurial efforts of Ed Sullivan and Jack Paar to give them TV coverage? The answer is undoubtedly yes. But the mass exposure they receive through American TV broadcasts by Sullivan and Paar (as well as NBC and CBS news) laid the groundwork for the Beatles success by presenting the group to millions of television viewers in the United States, and the world.

Ron Rodman is Professor of Music at Carleton College, where he teaches courses in the music and cinema and media studies departments. He has published numerous articles on tonal music theory, film music, and music in new media. He is author of Tuning In: American Narrative Television Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: The Beatles i Hötorgscity 1963, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beyond Ed Sullivan: The Beatles on American television appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KimberlyH,

on 2/22/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

Beatles,

paul mccartney,

1960s,

John Lennon,

gordon thompson,

please please me,

lennon,

mccartney,

Inside Out,

songwriters,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

george martin,

Parlophone,

Sixties British Pop,

Ardmore and Beechwood,

Brit Pop,

Dick James,

Helen Shapiro,

Northern Songs,

Sid Colman,

songwriting recording artists,

Southern Music,

nems,

Add a tag

By Gordon R. Thompson

Songwriting had gained the Beatles entry into EMI’s studios and songwriting would distinguish them from most other British performers in 1963. Sid Colman at publishers Ardmore and Beechwood had been the first to sense a latent talent, bringing them to the attention of George Martin at Parlophone. Martin in turn had recommended Dick James as a more ambitious exploiter of their potential catalogue and, to close the deal, James had secured a national audience for the Beatles. Nevertheless, as the band grew in popularity, James knew that McCartney and Lennon would attract the attention of other music publishers.

Most fans, unless they bought sheet music, were at best only vaguely aware that music publishers had any role at all in popular music, let alone that they controlled an economically critical part of the industry. Even Lennon and McCartney at first underestimated the importance of music publishing until probably the first royalty checks began arriving at manager Brian Epstein’s NEMS Enterprises offices. Every time someone purchased a recording of one of their songs—no matter by whom—both the songwriters and the publisher profited. And every play on the radio and every television appearance did the same.

The home of Britain’s music publishing industry resided in London’s Denmark Street, a one-block stretch of offices, studios, and stores near Soho, serviced by a small pub, a café, and a steady stream of aspiring songwriters. Dick James’s office sat at the corner of Denmark Street and Charing Cross Road, not far from the premises of Southern Music, Regent Sound Studios, and other music-centered establishments. Brian Epstein had walked into these offices in November with a copy of “Please Please Me” and the hope that James could break the Beatles into the national media. James delivered immediately, booking an appearance for the band on the 19 January 1963 edition of ABC’s television show, Thank Your Lucky Stars.

The traditional role of the music publishers was to plug songs, bringing them to the attention of artist-and-repertoire and/or personal managers in an effort to have them match compositions with performers; but rock and roll was changing that model. When EMI’s Columbia Records released Cliff Richard and the Drifters’ recording of Ian Samwell’s “Move It” in August of 1958, London saw the start of musicians performing their own music. The tradition only deepened with Johnny Kidd and the Pirates’ “Shakin’ All Over” in June 1960. American artists such as Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, and Carl Perkins routinely wrote and recorded their own material, unlike singer Bobby Rydell or many other pop stars who performed material written by professional songwriters. In Britain, songwriting recording artists often proved fleeting phenomena.

With “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me,” as well as a number of other originals that would appear on their first album Please Please Me, John Lennon and Paul McCartney demonstrated their ability to write and perform their own material with spectacular results. Nevertheless, they knew the model and their first efforts to write a song for another performer met with mixed results. Touring with Helen Shapiro, the two songwriters futilely attempted to convince her and her management to record their song “Misery.” Another performer on the show, Kenny Lynch happily picked up the tune and very soon other artists would be looking for songs by McCartney and Lennon. Dick James, perhaps worried that with greater success the two ambitious Liverpudlians (and their manager) might bolt for yet another publisher, sought a strategy that would keep them as clients.

Click here to view the embedded video.

McCartney and Lennon were not the only songwriting performers in London. Southern Music had contracted eager songwriters and willing performers John Carter and Ken Lewis (later the core of the singing group the Ivy League) to write for the publisher. Their mentor at Southern, Terry Kennedy had even dubbed their band the “Southerners” (with a young Jimmy Page on guitar). However, they tended to write tunes for other singers and to perform songs written by other songwriters, all under the umbrella of their publisher.

Dick James’s big idea was to have John Lennon and Paul McCartney become part owners of their own publishing venture: Northern Songs. The arrangement that Epstein, McCartney, and Lennon made with James must have seemed good at the time, especially given that most young composers had no income from their work other than their author royalties. Northern Songs rewarded the two Liverpudlians with a larger piece of the pie, dividing the ownership of company between (i) Dick James Music, (ii) NEMs, (iii) Lennon, and (iv) McCartney. Dick James Music held a 51% voting share, leaving Lennon and McCartney each 20%, and NEMS Enterprises picking up the remaining 9%; however, James also took a 10% administrative fee off the top, so that in practice, the songwriters and their manager shared about 44% of the income.

Lennon and McCartney already had an agreement with Epstein to write songs, but a company dedicated to their music brought the game to an entirely new level. This would not be the last time that they would be the first to explore new territory in the business, from which other rock and pop artists and their managements would learn.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Beatles and Northern Songs, 22 February 1963 appeared first on OUPblog.

Paul Is Undead Alan Goldsher

Paul Is Undead Alan Goldsher

Basic premis-- zombies walk among us. There are different types of zombies, depending on where the zombie was created. Some function well in living society, some are scary death monsters. Some play a mean guitar and turned some other good musicians into a band. Because Liverpool zombies are strong and artistic.

Except Stu, Stu became a vampire. And Ringo, Ringo's a ninja. (Yoko is, too.)

John Lennon had a vision of the first undead rockband. A zombie band, which caused some friction with another Liverpool band that was made up of living members, but called The Zombies.

Overall, it's the history of the Beatles, but with zombies. Pete Best gets fired because he refuses to turn. John didn't die in 1980, because he was already undead. Mick Jagger's a zombie hunter (they could have done a lot more with that plot line. It kinda fizzled.)

Overall... I liked most of it. The zombie stuff was pretty graphically gross, which isn't my cup of tea, but makes sense in a zombie novel. But there's also a lot of comic grossness, like that'll often rip their arms off to better beat each other with them. There's a good dose of teen boy humor in here.

I think Goldsher was really clever in how he made the zombie Beatle thing work. He especially excels at the strained relations between members. No one's dead, but everything still went down, so they're not exactly talking to each other and John's version of events often differs from other people's.

Format wise, it works really well-- (ok, the pictures were gross, but, that's a cup-of-tea thing, not an actual complaint.) It's an "oral history" so the conceit is that Goldsher is a rock journalist interviewing all the actors involved, and so it's all transcript form, piecing together different interviews like you would in a documentary. This really allows the strained-band-politics to shine. Interspersed are interviews with zombie experts, newspaper articles, and excerpts from books about zombies, to help with the world building, but in a really unobtrusive way.

My only real issue is that, after awhile, the premise wore thin and it wasn't enough to sustain such a long time span of band history or 300 pages of book. It got to the point where I was invested enough that I wanted to finish it, but had to slog through the last bit to get there.

Book Provided by... my wallet

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

In 1968, film maker and pop art legend Andy Warhol memorably stated: ‘In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes’.

I can clearly remember him saying these words. I was only twenty-four at the time, fresh out of the British Army’s Royal Corp of Signals, and steeped in the pop music culture of the era. And whilst not totally buying into the everyone part of Andy’s statement, there was still enough naïve hope burning inside of me to imagine that I might even yet fulfil my long held ambition of playing cricket or football for England. After all, the only missing ingredient as far as I could see was finding the right coach. Somewhere, there had to be a life-changing guru who was capable of bringing out the deeply hidden, international-standard sporting talent I’d surely been born with.

Where’s a Mystic Guru When You Need One?

Sadly, unlike the Beatles, whose association with a certain Maharishi Yogi the year before is alleged to have inspired several of the songs on the group’s White Album, no magical guru was destined to appear for me at this stage. It transpired that my turn for fleeting fame didn’t eventually come around until 1999, by which time you can’t blame me for having cooled somewhat in my belief of Mr Warhol’s theory. I mean, thirty-one years had passed by. Exactly how long was the queue at the ‘Make Me Famous’ desk in my little neck of the woods for crying out loud?

The truth is, I’d spent nearly three miserable years amongst the ranks of the unemployed during the recession of the early 1990s. With absolutely no educational or professional qualifications to my name and my fiftieth birthday party looming large on the horizon, any future employment of worth (let alone fame and fortune) appeared to be about as likely as wind-up gramophones and 78rpm records making a comeback. In fact, the only thing that kept me going through this dark period was writing a minimum of one thousand words a day on my latest novel. To heck with gurus, maybe it was to be some smart publisher who would eventually come riding to my rescue.

Yea, in my dreams!

The Oldest Schoolboy in Town

But then came a remarkable turnaround. In a last-ditch effort to get somewhere I applied to return to full-time education. And that’s when those early novels I’d written really did pay off. With nothing else to back up my suitability for this scholastic adventure, it was these manuscripts that turned out to be the keys to the college. As my only references, they certainly seemed to impress the right people, and in 1995 I began a two-year Higher National Diploma course in advertising copywriting. If I remember correctly, the average age of my class was just under twenty.

Welcome to the World’s Most Famous Advertising Agency

Right at the start of my college days I was told that: “Major league advertising is a young person’s business George, and however well you may do on this course, no big London agency will ever employ you.” This wasn’t meant as a put-down, just a realistic assessment of my post-graduation possibilities. I didn’t care. I’d started out not daring to hope for anything more than a job at a small provincial agency anyway. Even so, when a two-week work experience placement at the world’s most famous advertising agency, Saatchi & Saatchi, was offered, I grabbed it with both hands. OK, it might not lead to that desperately needed job, but I was going to make darn sure they noticed me. I remember writing nineteen radio ads in one day for a pharmaceutical product. None of these were ever used. But then the impossible happened. After my two-week stay there had been extended to three, out of the blue, I found myself more shook up than Elvis had ever been when the Creative Director offered me a full-time job as a copywriter. That is, if I wanted it.

Were they joking? If I wanted it? You could bet your house, your car, and even your favourite Disney character’s life that I did.

It’s Better Late Than Never, Andy

Six months or so after starting at Saatchi, the British media managed to get a handle on my story. And how, because I’d spent the last of my money on the train fare to London at the start of my work experience, I’d been forced to spend a few nights sleeping rough on the streets of London. Of course, the agency knew nothing about this at the time. To the TV, radio and press people however, this was a Cinderella type story that ran for several weeks.

Following the publication of my first novel, and with a good bit of help from my employers, I even managed a second bite of the fame cherry in 2000. But far more than anything I did myself, the magic of Saatchi’s name was what really created the headlines. I benefited enormously from the association. No wonder I love the fabulous TV series Mad Men.

I’d finally experienced my fifteen minutes of fame – twice over in fact. So Mister Warhol was right all along. Thanks for keeping me going Andy.

* * *

George Stratford’s latest novel, Buried Pasts, has recently been released by GMTA Publishing as both a paperback and electronically. The kindle version of this book has already been downloaded well over seven thousand times in the USA alone. In an official review, the much-respected publication, Publishers Weekly, described the story as: “A page-turner that blends suspense with a cast of characters who genuinely care for each other. It’s an engaging and satisfying novel for fans of adventure stories with a heart.”

Want to dig a little deeper? You can see other reader’s reviews, and get to read the opening three chapters of Buried Pasts for free on Amazon.com. Here is the link to use: http://goo.gl/czR3T About the book: Personal demons can be a killer

Even after eighteen years, Canadian pilot Mike Stafford still carries a powerful sense of guilt over the death of his best friend during a huge RAF bombing raid to Berlin in 1944. He eventually returns to England for an inaugural squadron reunion full of apprehension over what the visit may produce.

Siggi Hoffman, then a young German girl of twenty, also has terrible memories of a personal loss from that same wartime night. She too is unable to forget. Nor has she ever been able to forgive.

When fate throws these two together in a small north Yorkshire town during the summer of 1962, the past collides devastatingly into the present. And all the time, lurking ominously in the background, is an unknown enemy intent on extracting violent revenge. Personal demons are only one of the many problems that must now be overcome when Stafford and Siggi find themselves fighting to survive.

As long buried secrets are finally revealed, events reach a literally explosive conclusion.

PUBLISHERS WEEKLY REVIEW:'This page-turner blends suspense with a cast of characters who genuinely care for each other. It’s an engaging and satisfying novel for fans of adventure stories with a heart.'

If you enjoyed this article, you may like to know that George has also written a full novel length account of his time spent at Saatchi & Saatchi and in the media spotlight. What’s more, for a limited period, GMTA Publishing is offering a free kindle download of this light-hearted memoir to every reader who purchases a copy of Buried Pasts.

By: Lauren,

on 9/13/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

UK,

Beatles,

paul mccartney,

John Lennon,

This Day in History,

george harrison,

gordon thompson,

please please me,

ringo starr,

*Featured,

when did the beatles break up,

Add a tag

By Gordon Thompson

By: Lauren,

on 10/7/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

jesus,

happy birthday,

A-Featured,

Beatles,

paul mccartney,

thompson,

John Lennon,

george harrison,

gordon thompson,

please please me,

lennon,

everyman,

yoko ono,

ringo starr,

skidmore,

i am the walrus,

strawberry fields,

beatle,

indelible,

Add a tag

By Gordon Thompson

On 9 October, many in the world will remember John Winston Ono Lennon, born on this date in 1940. He, of course, would have been amused, although part of him (the part that self-identified as “genius”) would have anticipated the attention. However, he might also have questioned why the Beatles and their music, and this Beatle in particular, would remain so current in our cultural thinking. When Lennon described the Beatles as just a band that made it very, very big, why did we doubt him?

Today, the music of the Beatles remains popular, perhaps because it helped define a musical genre that continues to flourish, leading some to speculate that these songs and recordings express inherent transcendental qualities. Nevertheless, no graphed demonstration of harmonic relationships and melodic development and no semiotic divination of their lyrics can explain what these individuals and their music have meant to Western civilization. Those born in the aftermath of the Second World War harbor the most obvious explanations. A plurality of the children who came of age during the sixties continues to hold the Beatles as an ideal expression of that decade’s emphasis on self-determination and optimism.

The composer of “A Hard Day’s Night,” “If I Fell,” “Help!,” “Nowhere Man,” “In My Life,” “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “I Am the Walrus,” “Across the Universe,” “Imagine,” and other classics of the modern Western canon left an indelible mark on our notions of music and expression. Where Paul McCartney searched for polite answers to reassure adults, Lennon often seemed to taunt reporters, to the delight of adolescents and the adolescent at heart. When Lennon got into trouble (as he did when American Christians took umbrage at his comparison of fan reaction to the Beatles and to Jesus), we apprehended our own image in the mirror of his discomfort. Moreover, when he shed the conventions of adolescence for the complicated independence of adulthood, we followed his example, albeit usually with less flair and more humility.

In many ways, John Lennon represented a twentieth-century Everyman: someone in whom we could see ourselves re-imagined in extraordinary circumstances with a quicker wit and more charisma. His assassination thirty years ago in December 1980 consequently left an indelible mark on us, standing as one of those moments stained in memory and time. That he had recently emerged from a well-earned domestic sabbatical with renewed possibilities, which both he and his fans recognized, made his death all the more tragic.

Just as the Fab Four had helped to define adolescent identities, perhaps these same baby boomers recognized in Lennon’s death the fragility of our own existence writ large on the wall. And, as the writing hand moved on, we contemplated one last indisputable truth that this most poetic Beatle had bequeathed: the passion play of his life, career, and death had provided us with a sand mandala of our own impermanent individual selves.

Pop culture by definition presents a fleeting expression of our consciousness, which we perpetually construct and reconstruct; but we sometimes forget that the currents of culture have lasting effects on the swimmers. Lennon, Harrison, McCartney, and Starr may have only been musicians that made it very, very big; but, in their roles as ritual players on the altar of the sixties, they played out an extraordinary version of everyday universal lives.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties Br

By: Anastasia Goodstein,

on 8/3/2010

Blog:

Ypulse

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

MTV,

beatles,

abc family,

Sears,

glee,

Ypulse Essentials,

forever 21,

arcade fire,

dan brown,

j.c. penney,

justin beiebr fairly oddparents,

TransWorld,

Add a tag

MTV unveils 'MTV Crashes' (A global music event series that kicks off next month with Sean 'Diddy' Combs in Glasgow. Also ABC Family launches 'Chatterbox' iPad app to facilitate virtual fan viewing parties. ) (MediaWeek UK) (MediaWeek)

- Forever 21... Read the rest of this post

MTV unveils 'MTV Crashes' (A global music event series that kicks off next month with Sean 'Diddy' Combs in Glasgow. Also ABC Family launches 'Chatterbox' iPad app to facilitate virtual fan viewing parties. ) (MediaWeek UK) (MediaWeek)

- Forever 21... Read the rest of this post

By: Lauren,

on 7/29/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

edward said,

gordon thomson,

skidmore,

thagīs,

thagī,

example—attempted,

behm,

asians,

Music,

Film,

A-Featured,

Beatles,

help,

orientalism,

indiana jones,

hindu,

please please me,

yardbirds,

Kinks,

Add a tag

By Gordon Thompson

At the July 29, 1965 premiere of the Beatles’ second film, Help!, most viewers understood the farce as a send-up of British flicks that played on the exoticism of India, while at the same time spoofing the popularity of James Bond. Parallel with this cinematic escapism, a post-colonial discourse began that questioned how colonial powers justified their economic exploitation of the world. Eventually, Edward Said’s Orientalism would describe the purpose of this objectification as “dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” (1978: 3). In effect, Said and others argued that portrayals of the non-Western other—of which Help!, written by Marc Behm (who had also created Charade, 1963) would be an example—attempted (consciously or otherwise) to justify the myth of European racial superiority. Perhaps Behm, director Richard Lester, and the Beatles saw their film as in the satiric tradition of the Carry On film comedies popular in Britain and parts of the Commonwealth. But for Britain’s growing population of South Asian immigrants, the film would have been one more example of the dominant white culture twisting the identity of an economic underclass to serve the end of dominating it.

Most Westerners have never quite grasped the importance of the Hindu deity Kālī (presented in Help! as “Kāīlī”) and associated her with eighteenth and nineteenth century Indian organized-crime families (Thagīs, the root of the English word, “thug”), some of whom had worshiped her. As the goddess of time, Kālī also represents death, that great leveler of social classes and a figure both honored and feared. British governments fighting crime families profiled Thagī practices, such that for them mother goddess worship joined the list of criminal characteristics. Perhaps they also distrusted any religion that elevated a non-subservient feminine identity to the divine, and Kālī is anything but subservient. Subsequently, Kālī and Thagīs have presented irresistible conflated subjects for novels and films, even as recently as 1984 in the film Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

The culturally naïve world of the Beatles in 1965 experienced its own loss of identity control as others attempted to manipulate them, a growing disaster to which they contributed. Earlier that spring, a dentist had surreptitiously spiked Lennon and Harrison’s coffees with LSD at a dinner party in an attempt to ingratiate himself. And the Beatles’ extensive use of marijuana on the set of Help! had rendered them extras in their own film. However, early in the filming, the Indian instruments in one scene attracted George Harrison who would have already been aware of the interest in Indian music floating in the British air that spring and summer. A number of other musical compatriots had already been inspired by Indian music, from the Yardbirds (“Heart Full of Soul” in May) to The Kinks (“See My Friends” in July).

Over the next few years, Harrison would more deeply embrace Indian culture, especially music and Hinduism, and renounce the use of psychoactive drugs. Ironically, youthful Western audiences in the sixties created their own Orientalist vision of Indian culture by creating an association between Indian music and drugs and sex. Of course, their purpose was not to support British eco

Before we conclude this week--and because I have no other place to put this so it may as well go on my blog--I have two examples of the Beatles in popular culture that I ran across this week. If you pay close enough attention (and know what you're looking for) you will start to find their influence everywhere. In these two particular examples, they're used in advertising.

Exhibit A:

"All you need is loaf" button from Tillamook Cheese. (Sorry for the blurry quality.) A play, obviously, on the Beatles lyric "All You Need is Love." We received these from Tillamook reps who were promoting their products at a local grocery store earlier this week.

Exhibit B:

Bag from Lucky Brand Jeans store. Upon receiving it I thought,

That looks like it was inspired by the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band cover.

Then I turned the bag on its side and saw that it was designed by Sir Peter Blake. Who is most famous for designing the

Sgt. Pepper cover. So there you go.

Posted on 5/20/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

History,

A-Featured,

Beatles,

concert,

gordon thompson,

pop,

rolling stones,

mick,

lindsey,

hogg,

altamont,

jagger,

stones,

Add a tag

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he looks at May 1970 and the Beatles. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

For Beatles fans, it was like watching mortality embrace a loved one. The spring of 1970 brought news of the dissolution of the Beatles and, with the release of Michael Lindsey-Hogg’s Let It Be in May, fans could see the disestablishment for themselves.

Lindsey-Hogg had established his reputation with musicians through his involvement with the British television show, Ready, Steady, Go! In 1968, Mick Jagger asked him to direct a concert staged specifically for the screen, perhaps in imitation of D. A. Pennebaker’s Monterey Pop, filmed in 1967 and released in 1968. Lindsey-Hogg re-imagined the concert as a circus and captured a number of compelling performances (notably by the Who), which unfortunately did not include the culminating appearance by the Rolling Stones who went on last after a very long night. Lindsey-Hogg filmed The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus in December 1968; but Jagger and the others apparently decided against releasing it, disliking their performance.

One of those involved in the performances that night had been John Lennon, who had pulled together a band consisting of Eric Clapton (guitar), Keith Richards (bass), and Mitch Mitchell (drums) to accompany himself and Yoko Ono. The Beatles and Lindsey-Hogg had worked together on film shorts to accompany the release of the recordings “Paperback Writer,” “Rain,” “Hey Jude,” and “Revolution,” so his selection to film them preparing for a concert seemed natural.

In January of 1969, Lindsey-Hogg and his crew assembled in Twickenham, where the Beatles had worked on previous films. This time, however, without manager Brian Epstein’s attention to detail, the band found themselves in cold studios arguing with each other to the point where George Harrison walked out of the sessions. McCartney could only purchase Harrison’s return by dropping the idea of a major concert at the end of the sessions. The Beatles turned to the basement of their offices in Savile Row to continue rehearsing material and the concert devolved into a brief rooftop appearance.

What Lindsey-Hogg does manage to capture is a creeping alienation and disaffection brought about by a number of factors, not the least of which was the maturation and individualization of the Beatles. They had long ceased to be the Fab Four. The world had grown darker and their vision more serrated.

The Rolling Stones for their part engaged in their own disaster film, Gimme Shelter, directed by Albert and David Maysles with Charlotte Zwerin, which begins with their 1969 Madison Square Gardens performances and ends with the tragedy of the Altamont Speedway concert. The Stones had dropped

By: Rebecca,

on 4/13/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

History,

A-Featured,

Beatles,

1960s,

pop,

British rock,

Eddie Cochran,

twenty-flight rock,

Add a tag

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an  insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he looks at April 1960 and Eddie Cochran’s influence on the Beatles. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he looks at April 1960 and Eddie Cochran’s influence on the Beatles. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

One of the most remarkable developments in sixties pop culture came with the emergence of British rock ‘n’ roll. On the western side of the Atlantic, the genre had evolved from numerous sources, blending and diverging to produce a myriad of styles. British youth in the fifties gazed on the music of American performers like Little Richard, Bill Haley, Chuck Berry, and Elvis Presley with a combination of wonder and envy. The first British attempts came in the resurrection of American folk blues, which musician Lonnie Donegan called “skiffle,” but which increasingly included music hall ditties. It would take American mentors to help the Brits find their mojo. Of the various candidates eligible for that status, few can rival Eddie Cochran.

Cochran was a natural: good-looking, creative, talented, and ambitious. In addition to writing some of the most memorable rock tunes of the era, including the classic, “Summer Time Blues” (with manager Jerry Capehart in 1958), he appeared in the seminal rock film of the era, The Girl Can’t Help It (1956). In that film, he sings “Twenty-flight Rock,” the core of which was written by Nelda Fairchild, one of the few women writing this kind of material at the time.

Cochran’s particular significance for the British came during his tour with Gene Vincent in 1960. Performing with them, Marty Wilde and the Wildcats boasted several future notable British musicians, including guitarists Big Jim Sullivan and Tony Belcher, bassist Liquorice Locking, and drummer Brian Bennett. The Wildcats accompanied Cochran on most of the gigs and Sullivan remembers the American as a multi-instrumentalist who could show all of them on their own instruments what he wanted them to play. These musicians all went on to prominence in the explosion of British rock and pop in the mid sixties either as session musicians or as members of Cliff Richard’s influential Shadows and carried the lessons they learned from Cochran.

On the night of 16 April 1962, as Cochran and Vincent traveled in a taxi with another American, songwriter Sharon Sheeley, the car went off the road near Bath, England. The others survived with serious injuries, but Cochran would die the next day. His death, and that of Buddy Holly the year before, set off a flurry of posthumous record releases over the next three years, whetting the British appetite for American rockabilly. Performers like Heinz (“Just Like Eddie,” 1963) tried to capture the spirit; however, as the supply of unreleased disks dwindled and the imitations became less convincing, one British band in particular stepped in to fill the void.

The nucleus of the Beatles had formed around Cochran’s recording of “Twenty-flight Rock” when Paul McCartney dazzled John

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an  insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he looks at March 1970. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he looks at March 1970. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

The year 2010 holds a number of Beatle decade anniversaries. In August of 1960, they headed off to Hamburg where they would endure a trial-by-fire, first in the Indra Club and then, the Kaiserkeller. Playing for four hours on weeknights and for six hours on weekend nights, they built both repertoire and stamina, if not musical skills. When they returned to Liverpool that winter, some of those who had known them before the journey barely recognized these rockers from Germany. Ten years later, in April 1970, Paul McCartney would announce his departure from the band and the dissolution of his songwriting relationship with John Lennon. Ten years after that in 1980, Lennon, born in 1940, would die at the hands of an assassin.

On 6 March 1970, a month before McCartney’s departure declaration, the Beatles released a fittingly titled final single: “Let It Be.” They had created the core of the recording over a year before in January 1969 during their ill-fated attempts at filming preparations for a spectacular performance. Now, as the band drifted into disintegration, an anthem materialized around their disconsolation.

“Let It Be,” with its references to his late mother and to the new reefs in McCartney’s professional and personal lives, evokes a religious resolution to his problems with organ fills by Billy Preston reminiscent of an American gospel service, a George Harrison guitar solo played through an organ’s Leslie speaker, and wordless backing vocals that fill the room like a church choir. It also references the instrumental line-up of the Band, Bob Dylan’s former backing group that had influenced other British groups such as Procol Harum and that had come to articulate a rural return-to-roots philosophy that appealed to McCartney.

When this Apple Records single appeared, McCartney could not have foreseen the version that would emerge on the album Let It Be, released after his departure. American Phil Spector, who had found favor with John Lennon and whom manager Allen Klein had hired to polish the production, superimposed an orchestration that converted McCartney’s county gospel service into a Hollywood spectacular.

“Let It Be” falls into a subcategory of McCartney’s catalogue that includes songs like 1968’s “Hey Jude.” In both songs, McCartney seeks to sooth troubled minds. “Hey Jude” addresses the disruption associated with John Lennon’s separation from his wife Cynthia and son, Julian. “Let It Be” seeks solace, perh

Literary mashups are taking over the world.

Mr. Darcy, Vampyre. Pride & Prejudice & Zombies. Sense & Sensibility & Sea Monsters. Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter.

And now…be still, my heart…the undead hordes have finally(!) smiled upon the GREATEST BAND in the UNIVERSE.

It was twenty years ago today, Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play.

They’ve been going in and out of style, But they’re guaranteed to raise a smile.

So may I introduce to you, the act book you’ve known waited for all these years…

PAUL IS UNDEAD: THE BRITISH ZOMBIE INVASION by Alan Goldsher

http://www.ispauldead.com/mediac/450_0/media/GreatHoax.jpg

Oh. Mylanta. My life can now be complete on June 22, 2010.

Why isn’t there a youtube book trailer for this? For the love of McCartney, somebody get on this one, stat!

Although you can’t nab copy of Paul is Undead for awhile, you can read about the brain munching escapades of John, Paul, George, and 7th Level Ninja Lord Ringo Starr here and here.

Hungry for more? Try my Happiness is a Warm Bundt Cake. When the undead come for your brains, lob a few sweet slices their way as a distraction.

2 sticks butter

3/4 cup chocolate syrup

8 (reg. size) Milky Way Bars, cut up (plus two more for later)

2 cups sugar

1 cup buttermilk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

4 large eggs, lightly beaten

2 1/2 cups all-purpose flour

3/4 cup unsweetened cocoa

3/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

Heat the oven to 325 degrees F. Grease 12-cup Bundt Pan.

In 4-quart microwave-safe bowl, combine butter, syrup, and nougat bars. Heat 5 to 5 1/2 minutes, whisking once. Whisk until smooth. Add sugar, buttermilk, vanilla extract and eggs. Stir in the flour, cocoa, salt and baking soda.

Pour batter into pan. Bake 1 hour 30 to 40 minutes or until wooden pick inserted in center comes out almost clean. Cool in pan on wire rack 10 minutes. Loosen cake from pan; invert onto rack to cool.

Melt some more Milky War bars w/ more milk and more butter. Pour goo over warm cake.

BINGE!

Posted in Book Reviews Tagged: Alan Goldsher, Beatles, Book Reviews, Happiness is a Warm Bundt Cake, Literary Mashups, The Undead, Zombeatles

3 Comments on Literary Mashups: Paul is Undead, last added: 1/22/2010

3 Comments on Literary Mashups: Paul is Undead, last added: 1/22/2010

By: Rebecca,

on 1/14/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Music,

History,

A-Featured,

Beatles,

british,

gordon thompson,

Kinks,

Shel Talmy,

The Who,

Add a tag

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he commemorate January 15th, a day two British bands released classic records. Check out Thompson’s other posts here.

A year after the Beatles stormed into American charts, British record companies continued to release disks that redefined how we hear pop music. Out of the seemingly endless stream of British performers flooding the international media emerged two performing songwriters with distinctly British voices. In one of the ironies of the era, on Friday 15 January 1965, two British bands released records that would become classics and both had the same American producer. Shel Talmy had relocated from Los Angeles to London with an introduction and faked credentials (he passed off the Beach Boys “Surfin’ Safari” as his own production) just before the Beatles and other bands lit the fuse of the “beat boom.” He had what few other British artist-and-repertoire managers had at the time: a great ear for hit songs, knowledge of how to elicit and to capture the excitement of performances, and an attitude big enough to push his ideas through to completion.

The Kinks premiered a song that Ray Davies had written as the follow-up to their breakout hit of the previous summer, “You Really Got Me.” Shel Talmy, although in favor of eventually releasing “Tired of Waiting for You,” wanted something that more clearly established a Kinks sonic identity. Consequently, for October release, Talmy, Davies, and the Kinks turned out “All Day and All of the Night” whose power chords and distorted guitar functioned the way the industry expected classic follow-up hits to sound. In January when the band appeared on ITV’s Ready, Steady, Go! to debut “Tired of Waiting” for Pye Records, the arpeggiated chords and nasal voice introduced listeners to a less aggressive and more melancholy Ray Davies. Instead of the hormonal lust of their previous two hits, “Tired of Waiting” spoke to an ambiguous ambivalence ambling about in that twenty-one-year-old heart. This would be the beginning of Davies finding his British voice. By the end of the year he would be skewering the well-respected men who rode trains into London’s City every morning.

Appearing on the same day, Brunswick Records unleashed the Who’s first single, “I Can’t Explain” for an expectant audience of London mods and to an unsuspecting world. Pete Townshend took the Rickenbacker electric twelve-string guitar that George Harrison had charmingly chimed on Beatles records over the previous year and turned it into a weapon. Shel Talmy allowed the band to play at club volume and compressed the sound so tightly that the guitar chords and drum hits project at the listener like spikes against a black background. Although Townshend would later complain about Talmy bringing in the Ivy League (John Carter, Ken Lewis, and Perry Ford) for backup vocals, the performances and the recording sound as crisp and cool as a mid-January night. Just as he had with “You Really Got Me” for the Kinks, Talmy

By: Rebecca,

on 12/18/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

favorite books,

Music,

Blogs,

A-Featured,

Beatles,

Prose,

bonanza,

gordon thompson,

please please me,

Can't Buy Me Love,

Add a tag

It has become a holiday tradition on the OUPblog to ask our favorite people about their favorite books. This year we asked authors to participate (OUP authors and non-OUP authors). For the next two weeks we will be posting their responses which reflect a wide variety of tastes and interests, in fiction, non-fiction and children’s books. Check back daily for new books to add to your 2010 reading lists. If that isn’t enough to keep you busy next year check out all the great books we have discovered during past holiday seasons: 2006, 2007, 2008 (US), and 2008 (UK).

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Thompson is a frequent contributor to the OUPblog, check out his other posts here.

Once you begin writing about the Beatles, people feel little hesitation in asking your opinion about which books they should read on the fab four, usually with some special qualification. Just the other day, a woman asked me for advice on what Beatles biography I could recommend for her twelve-year-old daughter who had become infatuated with the band, but whom the mother wished to shield from the biological aspects of their lives. (I recommended Allan Kozinn’s short, but entertaining account of their lives, repertoire, and recordings.) Nevertheless, the dramatic arch of their story and the music they created remain a draw for generations born long, long after the years of Beatlemania. Indeed, the music of this era persists on college radio stations and in the iPods of students.

Since 1997, I have been coaching a seminar at Skidmore College where students comb through a variety of sources on the Beatles, in the process learning how authors spin their narratives. Over twelve weeks, teams of juniors and seniors compare biographies by Philip Norman, by Hunter Davies, and, of course, by the Beatles themselves in their Anthology (both in print and on video). How do different authors describe Brian Epstein’s death? How did the Beatles come to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show? They also examine the music through readings by authors such as Walter Everett and summations of their professional and recording career in

0 Comments on Holiday Book Bonanza ‘09: Gordon Thompson as of 1/1/1900

Saturday night, folks from my writers’ group came over for a RockBand/Guitar Hero night.

Writers’ Rocksgiving.

I never knew we had so many headbangers and fist pumpers in our scribbler’s gang.

And of course…Scarlet Whisper made an appearance with her signature encore: Helter Skelter on Beatles RockBand.

I lose all inhibition (and dignity) wailing Helter Skelter. Imagine a tone deaf Paul McCartney in Janis Joplin drag performing a Vegas Style lounge act rendition. That kinda sums it up.

Can’t stop myself. I love that song. It’s become my writing anthem.

When I get to the bottom

I go back to the top of the slide

Where I stop and turn

and I go for a ride

Till I get to the bottom and I see you again

Revision after revision after revision. You edit your manuscript until the sight of it makes you want to hurl all over your Chuck Taylors. And then you work on it some more.

Do you don’t you want me to love you

I’m coming down fast but I’m miles above you

You waver. One day, you believe you possess a glimmer of talent. The next (after your query incites a chorus of crickets), you embrace the enormity of your writing suckage.

Tell me tell me come on tell me the answer

and you may be a lover but you ain’t no dancer

You turn to your beta readers, your crit group, your spouse and your second grade teacher (or worse, your mom) to analyze what is wrong with your book.

I will you won’t you want me to make you

I’m coming down fast but don’t let me break you

You put your manuscript aside. You start a new project.

Tell me tell me tell me the answer

You may be a lover but you ain’t no dancer

You play the waiting game with agents. You persevere.

Look out

Helter skelter

helter skelter

helter skelter

Yeah,

Look out cause here she comes

And one golden day, you get a manuscript request (or two, or six). Maybe it’s a partial. Maybe it’s a full. You’re back on the roller coaster.

When I get to the bottom

I go back to the top of the slide

Where I stop and turn

and I go for a ride

Till I get to the bottom and I see you again

Yeah, yeah, yeah

Well will you won’t you want me to make you

I’m coming down fast but don’t let me break you

Look out

Helter skelter

helter skelter

helter skelter

Rejection? Maybe. Who knows.

She’s coming down fast

Yes she is

Yes she is

coming down fast

I can’t stop. The ride makes me hurl sometimes, but it’s too much fun to get off and walk away. Yep, I’m hopping in line again.

Here we go.

Tell me, dear ones, what’s your writing anthem?

Hungry for more? Writing junkies will enjoy my Black Magic Cake

Black Magic Cake

Ingredients:

2 sticks butter, cut into pats

3/4 chocolate syrup

8 Milky Way Bars (2.05 oz. each), cut into chunks

2 cups sugar

1 cup buttermilk (or add 1 tbsp. lemon juice to one cup regular milk)

1 tsp. vanilla

4 eggs

2 1/2 cups flour

3/4 cup cocoa (dark choc. Hershey’s is best)

3/4 tsp. salt

1/2 tsp. salt

1/2 tsp. baking soda

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Grease 12 cup bundt pan. Put butter, syrup, and Milky Ways in a la

By:

Paula Becker,

on 10/20/2009

Blog:

Whateverings

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

cartoon,

General Illustration,

songs,

beatles,

paula becker,

The Beatles,

Warm Up Drawings,

music,

drawing,

Add a tag

I’ve been Beatles-obsessed the past month or so. Maybe it’s all the new Beatles products that have come out (The Beatles Rock Band gameplay, the remastering of their catalogue…) that’s got me interested in exploring them afresh. Also, with today’s internet you can easily explore The Beatles history, music, movies, etc. Mostly, though, I’ve been [...]

By:

Paula Becker,

on 9/30/2009

Blog:

Whateverings

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

drawing,

dogs,

cartoon,

General Illustration,

painting,

beatles,

paula becker,

Hard Day's Night,

reading,

Add a tag

I was working on these two guys and decided to give them some context, inspired, I’d say, by my late night readings of The Beatles Anthology book before going to sleep.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Last week Thompson stumped us with a musical riddle that had sixties British rock and pop as its subject. The answer and explanation are below. Check out Thompson’s other riddles here.

The Beatles’ Abbey Road, Released 26 September 1969

Forty years ago, as college students returned to their classrooms from that summer’s music festivals, as other students dropped out of school to join the “counterculture,” and as still others headed for Vietnam, the Beatles released one of their best-loved albums. After an acrimonious winter of false starts, the Beatles asked George Martin to return and to help them record in the way they had during happier times. In the few short years since the recording of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band (1967), their manager Brian Epstein had died, they had formed their own record and production company (Apple), they had retreated to Rishikesh in India to meditate, and they had seen much of what had taken them so long to build begin to crumble from within. The more they became involved in the business of being the Beatles, the less they seemed to enjoy it.

The Beatles sensed their impending demise as a functioning ensemble and, over that alternately turbulent and ecstatic summer, they pursued two visions of what they wanted to do musically. No longer simply four teenagers exhilarated with playing rock ‘n’ roll in strip clubs, dance halls, and subterranean clubs, they knew that the music world had evolved around them. When they first topped the charts, their music challenged the status quo of pop: the world of teen idols promoted by Dick Clark and saucy black women produced by Phil Spector or Berry Gordy. By September 1969, Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, and Ginger Baker (with Rick Grech) had formed Blind Faith, released an album, and were already in the throes of dissolution while the Jimi Hendrix Experience had played their last gig. The summer had featured a number of important music festivals featuring live music by many of the best-known performers of the era; but the band that had jumpstarted it all in 1963 was nowhere to be seen. Indeed, John Lennon would appear with Eric Clapton as members of the Plastic Ono Band in Toronto on 13 September 1969, suggesting that the Beatles were no longer able to function as a musical ensemble.

Although the Beatles discussed other names for this album (including Everest, suggesting the pinnacle of their recordings, albeit also the name of a cigarette brand), they settled on the name of the street where they had recorded in the EMI Recording Studios. The first side resembles the kind of album they had made in the past: individual recordings with no internal linking. Side two, however, attempts to join a number of songs together in part through performance, but also by simply splicing together different recordings.

The last begun, but not the last;

The end was coming very fast.

Although Abbey Road would be the last album project that the Beatles would begin, it would not be the last album they released. The fiasco of trying to film themselves rehearsing and then playing in a concert—material that would later prove the basis for the film Let It Be—American producer Phil Spector would take the tension riven sessions of early 1969 and turn them into the album Let It Be, which they released in 1970. Not only did the Beatles sense the end quickly approaching, but the album Abbey Road also officially comes to completion with a song called “The End.”

Why did the chickens cross the road?

Maybe they had a heavy load.

Although they discussed the idea of a portrait of them posing in the Himalayas (apropos of the possible title Everest), they instead chose a much closer location: walking across Abbey Road, a few hundred feet from the front door of EMI’s Recording Studios. These facilities were where they had gotten their break, where they had made their historic recordings, and where fans had regularly congregated to greet them. While hardly chickens (I just could not resist the reference to the classic joke), the cover photo has inspired considerable interpretation, if not imitation. For those convinced that the Paul McCartney had died in a car crash and that the Beatles management had brought in a double, the image of John Lennon in white (the priest), Ringo Starr in a dark suit (the undertaker), a barefoot Paul McCartney in a suit (the corpse), and George Harrison in denim (the grave digger) proved too much to resist. Moreover, one of the closing numbers, “Carry that Weight,” itself became part of the PID (“Paul Is Dead”) rumor mill tied to the cover.

They come together and salute the Queen;

But something happens in between.

To open the album, John Lennon provided a song he had initially written for Timothy Leary’s bizarre campaign to become the Governor of the State of California. But like many other things in his life, Lennon had grown suspect of the benefits of LSD and the intentions and abilities of people like Leary. “Come Together” instead contributes some of Lennon’s darkest verbal gobbledygook since “Glass Onion” and grows from a snippet of a Chuck Berry tune.

At the very end of the album, indeed even after “The End,” they place a bit of McCartney whimsy that pokes affectionate fun at the Queen. They did not list “Her Majesty” in the contents of the album, but instead left it an uncomfortable distance from the sentimental ending (“The love you take is equal to the love you make”) of the closing medley. Just as the almost discarded edit had surprised them in the studio, they intended it to startle listeners the first time they waited for the tone arm to head into the end groove.

But perhaps the most surprising aspect of this album is George Harrison’s “Something.” Positioned immediately after “Come Together” (and on the other side of that single), “Something” would be their biggest hit of the fall and ironically Frank Sinatra’s favorite Lennon-McCartney tune.

By:

Paula Becker,

on 7/8/2009

Blog:

Whateverings

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

beatles,

quebec,

concert,

2009,

beaconsfield,

july 7 2009,

summer,

Sketches,

General Illustration,

sketch,

Add a tag

Though it’s officially summer, you wouldn’t know it by the cool and wet weather we’ve been having since summer began. It’s caused outdoor activities to head indoors, such as the concert-in-the-park I went to see last night. Normally I don’t go to these when they’re forced to be held indoors, but a friend asked me [...]

Here's a little something to get you in the mood for Shakespeare's birthday tomorrow: a skit based on Midsummer Night's Dream. How cute is Ringo's roar?!

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the original post below he looks at The Beatles in late 60’s Britain.

Forty years ago, on 11 April 1969, the Beatles released “Get Back” / “Don’t Let Me Down” as their second 45-rpm single for their semi-independent label, Apple. In the spirit of an era when live performance had roared back into prominence, the Beatles had begun to feel trapped by their decision to abandon the stage for the studio. This recording represented an attempt to “get back” to their vitality as a band. Ironically, even in the first year of Beatles recordings, artist-and-repertoire manager George Martin and his balance engineer Norman Smith had routinely spliced together different takes to create iconic hits such as “From Me to You,” “She Loves You,” and “This Boy.” “Get Back” would undergo a similar reconstruction. Still, these April 1969 recordings endeavored to re-capture the excitement of live performance.

But the world into which they ushered this music moved differently than the heady days of 1963’s Beatlemania. Britain’s musical, social, and political climate boiled in the stew of late sixties change. In April 1969, Parliament reduced the voting age from 21 to 18 enfranchising and empowering its “bulge” generation and recognizing their powerful influence over culture. Similarly, immigrants from the British Commonwealth transformed the fiber of daily British life and infuriated right-wing politicians and hooligans who resented the social change. And indigenous intolerance flourished as Northern Ireland’s tensions between Protestants and Catholics erupted into firebombs. We rightfully remember the sixties as an era when new paradigms clashed with established prejudices. Throughout 1968, young British mods had latched onto a new music, embracing Jamaican reggae and ska such that on 16 April 1969, Desmond Dekker and the Aces would see their “The Israelites” become the first reggae tune to capture the top spot on many British charts.

In this turmoil, the Beatles struggled to find their place. John Lennon had voiced his political ambivalence in “Revolution” and George Harrison’s “Piggies” chastised the ruling class he had always resented. Paul McCartney’s songwriting fell back upon his love of character studies (“Michele,” “Eleanor Rigby,” and “Lady Madonna”) and his inherent ability to mimic musically (the music hall in “When I’m Sixty-four” and even reggae in “Ob-la-di Ob-la-da” where he references Desmond Dekker).

“Get Back” (built around a groove á la Frankie Lane’s “Rawhide”) became McCartney’s vehicle for social commentary, ostensibly about the desire to return to a simpler style of life (which he would embrace with his farm in Scotland) and briefly about racial politics. McCartney had floated a text intended to ridicule Enoch Powell’s incendiary Birmingham speech of 20 April 1968 in which the conservative had declared that immigration led him, “Like the Romans…, to see ‘the River Tiber flowing with much blood’.” McCartney’s awkward parody joked that Pakistanis who crowded council flats should get back to where they once belonged. Unfortunately, McCartney lacked Lennon’s or even George Harrison’s verbal knack for satire, and he dropped the idea.

Instead of a verse about immigration, and perhaps as a predecessor to Ray Davies “Lola” (recorded a year later), McCartney retreated to character study: Sweet Loretta Martin who, although a man, believes herself to be a woman. Unlike Ray Davies who quite happily accepts Lola’s trans-gendered identity, McCartney seems to urge Loretta (like the Pakistanis) to get back to where she belongs.

Unfortunately, the text and music lacks much of an obvious sense of irony, more a comment on McCartney’s lyrical skills than to any characteristic prejudice. Still, the Beatles would make their own statement on racial and cultural tensions by inviting American Billy Preston to join them on electric piano and crediting him on the record label, something they had not done with Eric Clapton (“While My Guitar Gently Weeps”) and certainly not with Nicky Hopkins (“Revolution”) and Andy White (“Love Me Do”).

The Beatles knew something had come undone when they needed an outsider to help them work together. Preston and Clapton only reinforced the internal belief that a door was closing.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the original post below he looks at the Beatles 45th anniversary of being on the Ed Sullivan Show.

For the Beatles, the month of February holds particular significance. Forty-five years ago on 9 February 1964, the Beatles made their official American debut on the Ed Sullivan Show and we have not been the same since. Adolescent America had anticipated the event, abandoning their normal anti-social isolation, positioning the family in front of the television, and ensuring that the CBS eye logo appeared on the screen. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” sat at the top of most American charts and the buzz of expectation now deafened anyone who would listen. When Ed Sullivan started his introduction and the audience screams erupted, we experienced one of those singular events in western history as a significant portion of North America temporarily stopped breathing.

But the Beatles had set down the path to the Ed Sullivan Show two years previously in what must be one of the most remarkable weeks in music history. On Monday 5 February 1962, the Beatles’ drummer Pete Best fell ill and the band recruited an old friend from a rival band. Ringo Starr appeared that night with John, Paul, and George in Southport, a city just north of Liverpool. Decca Records had just informed the Beatles that they would not be signing a recording contract. Perhaps Starr’s dry humor helped spark optimism that would get them through the month, just as his personality would help anchor them as America exploded around them in a February two years later.

The next day, Tuesday 6 February, the Beatles manager, Brian Epstein argued with Dick Rowe at Decca’s headquarters in an attempt to change his mind about rejecting the Beatles. Rowe, the head of artists and repertoire, notoriously and condescendingly informed Epstein that guitar groups were passé and that he and Decca’s sales manager, Sidney Arthur Beecher-Stevens recommended Epstein return to record retailing in Liverpool.

Liverpudlians do not fold so easily. On Wednesday (two years to the day when the Beatles would arrive in New York), Epstein met with Tony Meehan, the former drummer of the most famous guitar group in Britain, the Shadows and who had been at Decca the day the Beatles had auditioned, to talk about an independent production. Meehan would produce and have his own hits in 1962. Still, little about the meeting seemed to satisfy Epstein and yet another great moment of potential slipped into history, but the planets were still moving. By Thursday, they began coming into alignment.

On 8 February, Epstein walked into the Oxford Street HMV store to visit with the record store manager and to use the services of the house engineer who could transfer at least some of the Beatles failed audition from tape to disk. The engineer, Jim Foy, liked the Lennon-McCartney tunes and put Epstein in touch with another occupant of the building, Sid Colman, the head of EMI’s publishers, Ardmore and Beechwood. Colman in turn contacted George Martin of Parlophone Records and helped arrange a meeting the following Tuesday between the band manager and the artists and repertoire manager.

The end of the week found Colman and Martin meeting, no doubt discussing the polite and endlessly effusive businessman and his oddly named beat group. They could not know that in two years from that day, the Beatles would smash through American television screens and into the lives of millions. By the weekend, Epstein was writing to Decca informing them that the Beatles had arranged for a different company to record them. He exaggerated of course, but perhaps he could feel the momentum building, if not the sting of Rowe’s comments fading.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. In the post below he looks at “The White Album”.

“The White Album”: One need not say much more to evoke the alternately dreamlike and daunting experience of encountering the Beatles’ 1968 magnum opus. The year 1968 shaped our aesthetic  interpretation with student riots in Europe and race riots in the U.S., assassinations (Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy), political repression (in Chicago and Prague), and the inevitable loss of innocence as pop psychedelia began unraveling into drug addiction and death. What had begun in exhilaration and optimism had crested the hill and now careened in descent towards dissolution; but for the moment, the Beatles’ eponymous double album offered a breathtaking vista of monkeys, tigers, and blackbirds entertaining kings, queens, children, cowboys, and Jamaicans. Their sentiments could range from deep inside love (“I Will” and “I’m So Tired”), through outright sarcasm (“Sexy Sadie” and “Piggies”), to sheer terror (“Revolution 9”).

interpretation with student riots in Europe and race riots in the U.S., assassinations (Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy), political repression (in Chicago and Prague), and the inevitable loss of innocence as pop psychedelia began unraveling into drug addiction and death. What had begun in exhilaration and optimism had crested the hill and now careened in descent towards dissolution; but for the moment, the Beatles’ eponymous double album offered a breathtaking vista of monkeys, tigers, and blackbirds entertaining kings, queens, children, cowboys, and Jamaicans. Their sentiments could range from deep inside love (“I Will” and “I’m So Tired”), through outright sarcasm (“Sexy Sadie” and “Piggies”), to sheer terror (“Revolution 9”).

These recordings still hold the ability to capture our collective attention and individual fantasies, reminding us of how new and exciting music was. The album begins with a tip of the hat to the Beach Boys (and indirectly to Chuck Berry) as a jet roars into “Back in the USSR” (even as the USSR roared into Czechoslovakia). As the jet’s roar fades into “Dear Prudence,” we begin to wonder if this song about Mia Farrow’s introverted sister shields some darker purpose in the thicket of bass and drums. McCartney and Lennon seem to be talking about two different realities. Journalists of the time gossiped about the impending dissolution of the Beatles, sensing the internal tensions and multi-polar tug of personal interests. Listeners wondered about the future of civilization.

Forty years ago on Friday 22 November 1968, the Beatles’ commercial venture, Apple Records, issued their anti-Sgt. Pepper’s album, The Beatles. Gone were Peter Blake’s pop art colors and crowded imagery. The Granny Smith apple, known for its sourness, replaced the aura of fab-four comradery—of first moustaches and satin band-uniforms—with individual portraits and collaged domestic snapshots spread like memories on a bed sheet. Now, like other groups of the era, the Beatles sought to re-imagine themselves more as individuals than as a group.

The very same day that the Beatles released their eponymous “white album,” Pye released The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (with catchy Ray Davies’ tunes like “Picture Book”). Two weeks later, the Stones would finally see their own much-delayed Beggar’s Banquet released, with its carefully constructed DIY sound. But the Beatles would dominate the Christmas market that year, even as they inspired a cottage industry of cryptographers who believed they had deciphered from John Lennon’s clues the meaning behind Paul McCartney’s apparent death in a car crash. Lennon, when interviewed by a young teen from Toronto, spoke about multiple layers of meaning in the music, even as he backed away from the youth’s interpretations. Indeed today, we still find ourselves disaggregating the sounds and words of this compilation, wondering what it all means…, if anything.

We look back on this era and see a generation trying to make sense of the chaos, searching for meaning in songs and art. Perhaps we see ourselves trying to understand our selves, wondering what our future might hold, just as the Beatles struggled with these issues. Perhaps in repeatedly returning to this album, we continue to ponder our choices.

I spent yesterday morning with 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th grade students from Oak Mountain Academy in Carrollton, GA, reading and discussing my YR series,

Cynthia's Attic.

At first, I was a little leery about reading my books to 2nd graders, but they were wise beyond their years! The Missing Locket is set in 1964, with twelve-year-old best friend, Cynthia and Gus listening to a Beatles record. I mistakenly assumed that these youngsters wouldn't have a clue as to what a record, record player, and especially, what a Beatle was!Was I ever wrong!

When I pulled out an old circa 1963 Beatles album, they not only knew what records and record players were, one student shouted, "I have that album and listen to it all the time!"

To say my chin almost dropped to the floor wouldn't be much of an exaggeration. My morning with these delightful students was a satisfying, but humbling experience and reinforced my opinion that you should never assume. (We all know what happens then!)