new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: How to write, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 145

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: How to write in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

I talked with an editor earlier this week about my new novel, The Blue Marbles, a sff YA and found that editorial input comes in two forms–and these are so important to finding the right editor for your story.

Positioning in the Market Place

The first thing we talked about was our visions for the story, to see if we meshed. This is very much a marketing discussion. Where does the story fit into the marketplace? Who would read this book? Is this a middle grade or a YA?

Vastly important, you must know your audience because it determines so much of the next question about the quality of the story. If my story is a YA, it means that I need to follow certain conventions of the genre. The protagonist should be of a certain age; he’s got a certain outlook about dating and girls; he’s reacting to family in certain ways. It brings up questions such as should he be able to drive or not? If the story is middle grade, the tone of the story would be very different. The answers to the questions would be vastly different.

Even saying that it’s a YA, isn’t quite enough. Is it a young-YA or is it closer to the New Adult category? In other words, will the tone of the romance involve just a brief kiss or something much more physical.

What happens when you disagree with the editor’s opinion of where to best sell this story? I’ve seen writers struggle with this because they want to write a YA. They read YAs; they talk YAs; they live YAs. But when they write, what comes out is a middle grade. Sigh. It’s frustrating. What you love isn’t necessarily what you can write. (At least not yet.)

YOU want to push the story to a YA; the editor wants to push it to middle grade BECAUSE she thinks s/he can sell the story there.

In some ways, this is a career question and not just an editing-this-novel question. Where do you have the best chance of creating a career for yourself? HINT: It might be different than what you thought.

Writers are notorious for not SEEING clearly what we write. Sometimes, you have an inkling that, well, this might be middle grade instead of YA. But you don’t WANT it to be MG; you love YA. Sorry.

An editor’s strength is that s/he has a pulse on two things: great story writing and marketing great stories. For an editor, those two things must match up. And you, as the writer, must either trust that editor or find a different one. You must also decide if you want a career based on the editor’s positioning of the book in the marketplace. If it’s positioned as a middle grade, can you–do you want to–follow up with a second middle grade? Because careers are built on building a readership who consistently comes to you for a certain type of story.

When a manuscript sells, your first thought is celebration! Yahoo! Your second thought is, “What next?” To build a readership, what story is the logical follow-up. When someone reads THIS story, which of your possible stories would they naturally pick up next and love just as much or more?

This question of the editorial marketing vision for your story is crucial. You must share your editor’s vision for the story. Otherwise–it may not be the best fit for you, your story, and ultimately, your career.

Tell the Best Story Possible

The second thing a great editor can do it help you create the best story possible, given the shared vision.

For me, the discussion had some themes I’m familiar with:

Setting. While my natural world settings were strong, when the story veered into a school–where the YA would be very apparent–I need more work. Setting is crucial to making sure the reader is grounded in your story.

Raise the stakes. The editor suggested a change that would raise the stakes of my story. The reader should always be invested in finding out what happens next, and if you can put more at risk, the stakes pull them through the story.

Emotional resonance. On a similar note, the emotional story should resonate with the reader and impact them in some way.

Everything we discussed seemed reasonable and necessary because we were heading toward a mutually agreed upon goal. Without the shared vision, the specifics of a revision are agonizing; with a shared vision, revision is like dancing with a friend, where you mirror each other’s moves in perfect harmony.

By Candy Gourlay

One lazy evening, while googling Jackie Chan fight scenes (as one does), I found myself watching this video by Tony Zhou (of the Every Frame a Painting YouTube channel):

In his video, Tony points out that Hong Kong director and action hero Jackie Chan blends comedy and action in a way that Western directors do not. The film lists ways by which Jackie Chan manages to create action with a comic twist.

As I listened to Tony's pointers and watched Jackie Chan twirling gracefully through fight scene after fight scene, I found myself having little epiphanies - not about action comedy, but about writing.

Jackie Chan always starts by putting himself at a disadvantage.

One of my favourite Jackie Chan fight scenes is when he loses his clothes while being chased by his enemies

"No matter what film Jackie always starts beneath his opponents. He has no shoes, he's handcuffed, he has a bomb in his mouth." This is the fun of a Jackie Chan movie - the bumbling no-hoper overcoming incredible odds and enemies - gangs of Kung Fu masters, mafia goons, cowboy baddies, what have you. In the end of course the joke is on his opponents who didn't see Jackie Chan coming.

It's a reminder to us fiction writers that

characters need to change.

If you're writing a coming of age story, your character at the start will be a child, innocent, naive. Your job is to grow your character into maturity. If you're writing a romance, your character must start out loveless or unloveable before you can begin introducing love opportunities. If it's an adventure you're building, your character must begin the story in a state that is the polar opposite of his ordinary world, in the way that Luke Skywalker lives in a boring moisture farm before he goes off to fight Star Wars and Harry Potter has to sleep in a tiny cupboard under the stairs before going off to live in magical Hogwarts.

|

Harry Potter and Luke Skywalker:

from zeroes to heroes |

The unputdownableness of a story is dependent on a reader's desire to keep reading. A reader only keeps reading

if they want to find out what will happen to the character.

Jackie Chan uses his world to move plot.

Jackie's famous ladder fight sequence

One of the delights of a Jackie Chan movie is Jackie's creative use of his environment in a fight. He uses everything. He backflips through ladders, duels with chopsticks and Lego, parries with umbrellas, and in one iconic fight sequence, does combat by juggling a massive ladder. These scenes are funny as well as jaw-droppingly skillful.

Every story has its own particular world - and the crafty writer will infuse that world into every aspect of his or her storytelling. It's not easy, but it builds the truth of your characters and helps the reader embrace your creation. I recently finished writing a story set in a pre-Christian, tribal setting. I had to think carefully as I told my story from the point of view of my tribal characters - every metaphor had to be based on their realities - birds, trees, weather. It was difficult but very satisfying.

Jackie Chan likes clarity.

When his opponent is in black, he's in white. That's in order for the viewer to see clearly what's going on. Not for him the handheld and dolly shots of Western film making that create a false dynamic, making actors who don't know how to fight look dangerous.

In one example, a fighting sequence that ends with a spectacular fall is shot making sure that the staircase is kept in the frame. Thus the viewers become familiar with the landscape and there is no geographical confusion when the fall actually happens. The viewers know the stairs are there, they know how high it is. They know the fall is coming, they are anticipating it. Anticipation is good, it keeps readers reading. The trick is to deliver what is anticipated ... and still manage to surprise.

Clarity is essential to a fiction writer's craft.

Every event must make sense within the world you created. Every decision a character makes must be true to who the character is. Our task as authors is to keep our readers immersed in our world. If something suddenly doesn't make sense, we will have woken our readers from their fictive dream. 'I couldn't believe the character would do that.' 'Why did she love him? He was so unloveable?'

The staircase example also reminded me of one of the best ways to hide exposition. You don't want to interrupt an important moment to explain something.

You must make sure you've craftily fed the necessary knowledge to your reader long before it is needed. JK Rowling was fantastic at this. (SPOILER ALERT) Scabbers, Ron's pet rat, appears in the every book until his true identity is revealed in

The Prisoner of Azkaban. In that book, Hermione's mysterious ability to be everywhere is revealed to be the work of a time turner - which is the very tool they use to save Buckbeak and Sirius Black. Throughout the book, we know stuff and yet what we know still holds a surprise at the end. Neat!

|

| Scabbers lives in the background until his true identity is revealed. |

Action and Reaction

Over and over again, the narrator mentions action and reaction. Jackie Chan's visual logic requires that action and reaction appears in the same frame (3:16). You see the punch, you see Jackie recoil. It's part of Jackie Chan's obsession with clarity.

It amazed me because action and reaction is something I obsess over when I'm writing new scenes. In fact, I will often scribble 'CAUSE AND EFFECT' on the top of the page when I'm plotting. This is because I've learned that it is action and reaction -- cause and effect -- that creates the feeling of movement in a story.

A story is not just pretty writing. As I said before, for a piece of writing to be a story, there should be change at its heart. If there is no change there is no story. And what makes the reader feel that change? Cause and effect. Action and reaction.

Jack is poor ... so his mum sends him to sell their cow ... so Jack sells the cow ... but the buyer has no money except "magic" beans ... Jack accepts the beans ... and angers his mum ... who throws them out the window ... and they grow ...It's a chain of events, connected because one thing leads to the other.

I used to sweat over plotting. I still do ... but thinking about action and reaction has made the task less excruciating.

Jackie Chan makes sure you see what's important

According to Tony's video, Hong Kong directors like Jackie cut fight scenes differently from their Western counterparts. After showing a wide shot of a fight sequence, they will cut to a close up of a pay-off strike (5:26) - it creates a rhythm but also a feeling of satisfaction in the audience to see the coup de grace in close up. The director is saying: check this out, notice this. It's important.

Writers are constantly quoting the adage: Show, don't tell. But the truth is you can't show EVERYTHING. There are times when you do have to tell, to keep the story moving. The skill is choosing wisely what you tell and what you show -

if it's important, it's got to be on stage. Show it, don't tell it. I've noticed that the medium of storytelling can dictate whether you're showing not telling - eg. in opera, all the big, important scenes are communicated in song because opera is about song. The opera singers

tell us what's going on. But opera is in the minority. If you're writing books (or making movies) you gotta put what's important on stage.

Jackie Chan does it in his fight scenes. You can do it in your books.

Jackie is patient

The little details that make a fight scene - the flip of a fan, the twirl of a ladder triple his height - are not achieved by pure talent. Jackie Chan is the first to tell you that it takes patience and practice. Jackie will practice relentlessly to get a move right - in the fan scene, he says it took 120 takes before he flipped the fan to perfection. As a small child he was sent to Peking Opera School - a boarding school that trained drama students in a version of martial arts that combined acrobatics, tumbling and performance.

This relentlessness is onscreen as well as backstage. Jackie Chan characters are never quitters. "He doesn't win because he's a better fighter, he wins because he never gives up." says Tony in his film. "It is a direct contrast to his American work where bad guys are defeated because someone shoots them."

We writers could use that relentlessness. One of the most important things I've learned since I began writing is:

There are no short cuts.

Need to patch that hole in the plot? Need to give your character a personality transplant? Need to start again? You gotta do what you gotta do. A rushed ending, a thin character, an unsatisfying plot - once the book is published there's no turning back, no hiding from readers and critics.

Jackie Chan earns his finish.

The final point in Tony Zhou's film is:

Earn your finish. 'Jackie's style (of film) always ends with a real pay-off for the audience. By fighting his way from the bottom, he earns the right to a spectacular finish.'

Personally I think all the internet sharing exhorting writers to create an opening to hook a reader/agent/editor has resulted in a crop of books with fabulous openings ... but exceedingly weak and rushed endings. Think back on all the great books you ever read. What do you mostly remember? I'll bet it's not the opening but that delicious, surprising, exciting ending. Once you're published what matters is not how you grab your reader but how you leave him when he's finished reading your book.

So ask yourself ... Does your ending leave your reader satisfied? Does your character deserve his ending? Has your character earned his finish? Have

you?

With thanks to

Tony Zhou for the brilliant video. Here are Tony's nine principles of Action Comedy:

The 9 Principles of Action Comedy

1. Start with a DISADVANTAGE

2. Use the ENVIRONMENT

3. Be CLEAR in your shots

4. Action & Reaction in the SAME frame

5. Do as many TAKES as necessary

6. Let the audience feel the RHYTHM

7. In editing, TWO good hits = ONE great hit

8. PAIN is humanizing

9. Earn your FINISH

Candy Gourlay also blogs on her author website. Read her most recent post Killing My Darlings.

Click cover to see the photo gallery.

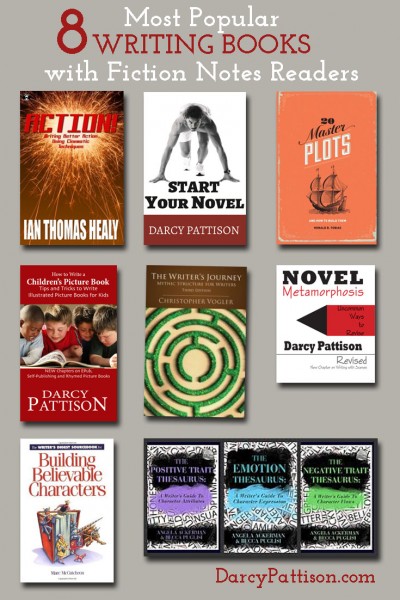

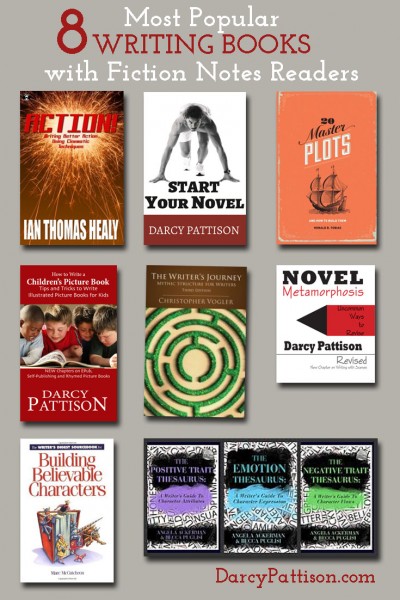

From time to time, we recommend writing books, and we find that some are popular with our readers. Following are the most popular how-to-write books purchased by our readers in the last six months on Amazon, the first half of 2015*.

-

Certainly one of my favorite new writing books is Ian Healy’s excellent book on writing action scenes. Before I read it, my action scenes were awful. Now, my latest novel has effective action scenes sprinkled throughout. Thanks, Ian! Be sure to also download the Action Scene Checklist that I created, with Ian’s permission. This was the most popular book, by far.

-

I was thrilled that my writing book came in second. Thanks, Readers. This helps you take an idea and develop it into a blueprint for a novel. Read more about this book.

I was thrilled that my writing book came in second. Thanks, Readers. This helps you take an idea and develop it into a blueprint for a novel. Read more about this book.

-

This book is a gem. I use it when I start a novel to help me nail down the genre. It also helps me plot because I am reminded of typical scenes in this type of story; I can choose to go against the grain or with the grain in plotting, but it gives me a sort of plumb line.

This book is a gem. I use it when I start a novel to help me nail down the genre. It also helps me plot because I am reminded of typical scenes in this type of story; I can choose to go against the grain or with the grain in plotting, but it gives me a sort of plumb line.

-

For the past two years, I’ve taught a class on writing picture books at the Highlights Foundation for Children, the home of the classic Highlights for Kids magazine. It’s a thrill to see this book on your list of favorites. Read more about this book.

For the past two years, I’ve taught a class on writing picture books at the Highlights Foundation for Children, the home of the classic Highlights for Kids magazine. It’s a thrill to see this book on your list of favorites. Read more about this book.

-

This is a classic and wonderful text that puts storied in the context of Joseph Campbell’s mythic structure. If you write any kind of quest story, fantasy, sff, then you need this. But it also works for romance, contemporary, mysteries–almost any genre.

-

This classic by Marc McCutcheon still delivers the goods. Need to create a character? You need this book.

-

When I teach my Novel Revision Class, this is the required workbook.

-

Sometimes, it’s hard to be fresh and original and you need a tool to help. The inner character traits (positive or negative) are one of those places that I consult a book like this. It just gives me a reminder of my options; of course, you then have to make the suggestion your own. But options are great. While the Negative Traits was the most popular with our readers, there’s also the Positive Traits and the Emotional Thesaurus from the same author.

* Note: these lists were compiled from reports supplied to us from Amazon.com where we are affiliates. One of the ways Fiction Notes is able to cover its costs and be a sustainable business is that we earn a small commission when readers make a purchase from Amazon after clicking on our links (including those above). While no personal details are passed on we do get an overall report from Amazon about what was bought and are able to create this list.

Try Book 1 for Free

My life is full and overflowing! My son is moving to Denver to go to school. I’m traveling and speaking a lot this month: see the Highlights picture book retreat and the Eastern PA SCBWI conference. In the midst of lots of busyness, how do you keep your focus on writing?

I’m taking a class.

Athletes stay in shape with zumba classes. Authors stay in shape with writing classes.

Especially when I’m busy, I like to take an online class because it gives me structure and makes me stay focused on the writing. Accountability is always a good thing; it’s crucial when days are swamped with non-writing activities.

Classes Give Thinking Points. Often when life is busy it’s because I’m traveling, which involves lots of down time. Sitting on a plane or in a car, there’s time to think. Some of you may actually be able to work in that situation, but I can’t. I’ll read a book about writing, publishing or general business, but I can’t really produce anything. Thinking, though, is often overlooked when I’m in a really creative mood and pouring out words. I find that thinking is a good use of travel time. Often, a book is enough. But when I can find a challenging class–delivered by email or an online video class–it keeps me learning.

Classes Give Challenges. Classes also give me a challenge. I look for topics, genres, strategies that challenge me to think in a different way, to try a different process, or even turn everything in my writing world upside down. I want to learn how someone else thinks about story, or how they create characters.

Sure, I teach classes. At heart, I’m a teacher; whenever I hear new information, my first instinct is to try to make it easier for the next person to comprehend, and most important for me, to apply it in a practical manner.

However, I am also a student. If I’m not stretching myself and learning more about my craft and my profession, then I stagnate. This month, when I’m off to teach at the Highlights Foundation, I’m also taking a class. It’s a perfect balance for me.

Find out more about Darcy’s Online Video Courses.

I am considering adding new online courses this fall.

Try Book 1 for Free

Darcy’s Note: In my question to understand action scenes better, I came across Ian’s book and was blown away by how practical it is. To make it even more practical I created an Action Scenes Checklist. To understand it and fully exploit it, you should buy his book and read it cover to cover. Yes, I’m that enthusiastic about it. If you plan ANY action in your story, you need this book. Stay tuned below for a chance to win a copy of this book and Healy’s latest novel.

Guest post by Ian Thomas Healy

Like many people, I love movies, and I have a special love for tight action sequences. I have always taken pride in my ability to translate that type of action into my books, and as a writer specializing in superhero fiction, action is an important component of my work. After years of being asked by my writer friends to help them with their own action sequences, it occurred to me that there might be a need for this sort of information across the industry, and so I sat down and analyzed what was it exactly that I did instinctively when I wrote action scenes, and how I might teach that to others. Thus, ACTION! WRITING BETTER ACTION USING CINEMATIC TECHNIQUES (http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0055LH0MU ) was born (naturally, during a running firefight with explosions and hair-breadth escapes).

A lot of writers dance around action, because writing it is daunting and uncomfortable. By its very nature, action is high-energy, full of motion and intense pacing, and for many writers, it’s a weird change from what they’re used to. At its very root, though, action is a means to resolve conflict, and conflict is the basis of all good storytelling, so it’s not something to run from (crashing through a window, sliding down a rooftop slope, and then dropping into a waiting convertible), but to embrace as an important part of your toolbox.

In ACTION, I break down what makes an action scene tick, from individual acts, called Stunts, up through Engagements (related series of stunts), to the all-encompassing Sequence, which contains more than one Engagement. Here’s an example of an action scene from my new book CASTLES, which released on April 1:

In ACTION, I break down what makes an action scene tick, from individual acts, called Stunts, up through Engagements (related series of stunts), to the all-encompassing Sequence, which contains more than one Engagement. Here’s an example of an action scene from my new book CASTLES, which released on April 1:

Sally rushed into the building. All she knew was in the space of a single breath, her entire squad had been taken out. Who were these guys, and how had they stayed under the radar so long? Parahuman criminals didn’t just appear out of the woodwork at random, especially when they were working as a team. There had to be records on these guys somewhere.

And then Sally ran across someone who could move nearly as fast as she could, and she was fortunate not to have been gutted like a fish by the barbed quills sprouting from the new combatant’s arms. He slashed at her and she twisted and dodged through the lobby of the building on full defense. Unlike the criminals two floors above, the guy attacking Sally wore less of a jumpsuit and more of a wrestling-style singlet. The quills seemed to grow all over his body and she thought of him as Porcupine Man.

Super-speed abilities were rare in the world, even more so than psionic powers, and yet this was the second speedster Sally had fought in as many weeks. “Is there a factory churning you guys out or something?”

Porcupine Man’s perceptions were apparently accelerated like hers, for he understood her despite her rapid speech. “The times, they are a-changin’.” He spread his arms wide and flexed his chest in a peculiar way.

Sally dropped to the floor as several quills whisked over her head to embed themselves in the reception desk, quivering like arrows. A sharp, burning pain shot down her back and she knew one of them had grazed her. She hoped like hell they weren’t tipped with poison. “That’s a Bob Dylan lyric. My husband loves that song.” She pulled her horseshoes from her belt.

“Maybe he can play it at your funeral.” Porcupine Man shot more quills at Sally and she threw herself backwards over the reception desk to put something solid between her and her opponent. With his speed, she only had a moment to decide on her next action, and she froze when she saw a terrified woman huddled beneath the desk, eyes wide, a quill poking out of her bloodstained blouse.

Sally had no time to check to see if the woman was severely hurt. She couldn’t stay hiding where she was and put the civilian in danger. Nor could she risk slowing herself down enough to offer any comfort. She heard the patter of Porcupine Man’s approaching footsteps and forced herself to move. She ran, leaning forward to make herself a smaller target. The slice on her back burned like a paper cut with lemon juice in it. He skidded to a stop and Sally knew she had an advantage over him, being able to stop and start instantly.

She glanced back and saw him fire another quill at her from his chest. It had gone from a veritable barbed forest to a sparse stand in just a few moments. His quills didn’t replace themselves very quickly. Maybe she could get him to use them up. She dove for the floor again, twisting herself around to land on her shoulder. The quill passed right over her face, close enough that she could see the wicked barbs on its tip. As she slid, she hurled one of her horseshoes at him. Normally, throwing away one’s melee weapons was a poor choice, but Sally had spent thousands of hours at the targeting range, learning how to throw things effectively. When accelerated by her super-speed arms, the most innocent objects could become deadly projectiles.

Her horseshoes were hardly innocent.

The iron ring caught Porcupine Man on his sternum, hitting him hard enough to send him flying back into a wall, which cracked with his impact. He fell amid a pile of broken drywall and didn’t move.

This scene represents a single Engagement in a larger Sequence, which is Mustang Sally’s team of superheroes versus a group of super-powered bad guys. There are several Stunts in this Engagement:

- Sally dodges as Porcupine Man attacks her in melee combat.

- Sally dodges again as Porcupine Man shoots spines at her in ranged combat.

- Sally dodges yet again as he keeps shooting at her (she’s having a rough go of it).

- Sally goes on the offensive and throws a horseshoe at Porcupine Man, taking him down.

In ACTION, I coach you on methods for writing these types of scenes on a step-by-step basis. When Darcy contacted me to say how helpful she’d found my book, it made my day, because any time I hear that I’ve helped someone to become a better writer, it makes the whole process worthwhile. If you find it a valuable tool for yourself, please don’t hesitate to post a review online and to let me know how it helped you!

Leave a comment and your name will be in a giveaway for a copy of one of Healy’s ebooks (Kindle, epub or pdf). There’s one copy each of ACTION! and CASTLE.

Try Book 1 for Free

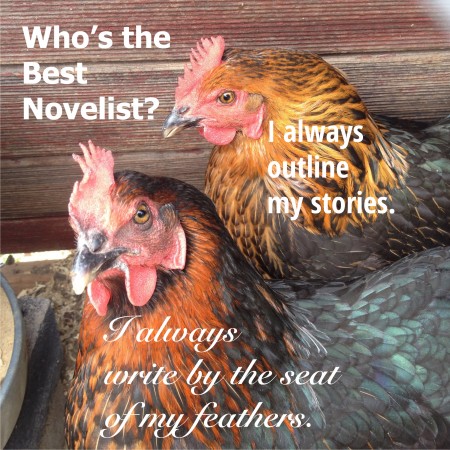

Last Friday, I wrote 4000 new words on my WIP novel. That’s a great day for me. But it was only possible because Thursday was a planning day.

When I work with students and teachers, I encourage lots of prewriting. My book, Writing for the Common Core, is essentially a book of prewriting activities. Here’s the thing: as professional writers, we know that our best writing comes with revision. That’s what students need to do, also: revise. However, that often devolves into merely copying a piece and cleaning up handwriting, especially in the lower grades. True revision, a re-envisioning of how to word something or the content to include/exclude, is hard to achieve in a 50-minute class.

Instead, I ask teachers to provide multiple prewriting activities. By giving students a rich and varied prewriting experience, they come to the first draft more likely to produce something worthwhile.

That’s what I did last Thursday, lots of prewriting.

Setting. One important thing for me was to locate my story on the slopes of Mt. Rainier. I used Google Earth to track the roads where my characters would be traveling. Using the program’s tools, I measured distances as the crow flies and distances along roads, so I knew how long each drive (and potentially chase scene) would take. I switched to the aerial view to look at the landscape–mostly wooded with some open areas.

Sensory Details. Once I knew where this section of the story would happen, I concentrated on the sensory details. What would they see, hear, touch, taste and feel? What would the day’s weather be like? Rainy, snowy, sunny, windy? Along with that, I thought about the mood of the events. Would the characters be frantic, excited, hopeful, angry, or bored?

Scenes. I also took time to sketch out the structure of a couple scenes. Scenes need a beginning, middle, end; add in conflict and a pivot or turning point; stir with some great emotional development. By planning ahead, I knew the general outline of what would happen.

Flexibility. With all the planning, though, I approached the writing with flexibility and let the moment carry the story forward. I “mostly” knew what I would write, but it always surprises me how much it changes and develops as I write. It’s never exactly what I planned; it’s usually better.

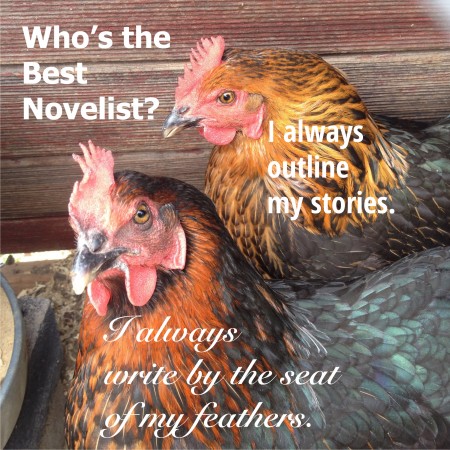

I’m not really an outliner; but I don’t write by the seat of my pants either. Instead, I need this half-way place, where I do rich prewriting activities and halfway plan, and then see where it all takes me. HOW you say something is everything. It’s not just what the story is or how well you plot. For me, the important thing is how you say it. What word choices do you make and why? What sentence structures and why? What pacing and why? The true writing happens when I write. But I love the prewriting because it enables me to get 4000 words done in a single day. Well, really, that was two days work: one to prewrite and one to write. Either way you count it, that was a couple great chapters to put behind me.

Anyone feel they haven’t read enough “how-to” books on writing?

Anyone feel they haven’t read enough “how-to” books on writing?

Claudia in Mendoza, Argentina, says she hasn’t finished reading John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction.

Go for it, Claudia—Gardner is one of my favourites. But before you go, take two minutes to consider my argument for becoming a writer from the inside out.

First, a confession:

Back in the 90s, I devoured the ‘how-to” gurus — Gardner and Hague and Vogler and Egri and Goldberg and Field and McKee and Campbell and Walter and Ueland and Dillard. Those books still adorn my office, their authors looking over my shoulder as I type. How do I get anything done?

I even wrote one of these books myself. I’m looking over my own shoulder!

That’s the answer, Claudia of Argentina–the answer to the “how-to” dilemma.

Write your own manual.

Thereby will you finally be able to unhook from “how-to.”

7 Suggestions for Unhooking from “How-to”

#1. Consume fiction

Read your brains out. Good fiction and bad. Savour, chew, and digest buckets of it. Reflect on how the best writers did it. How she moved you. How the hell did she make me cry? And laugh! I fall to sleep at night replaying the scenes that blew me away, the scenes that turned the story around. What happened there? How did she do it?

I fall to sleep soothed by the art of fiction

#2. Fall in love with the art of fiction.

Write like a lover. I remember watching sports on television as a kid, and how the instant the game ended we’d bolt out the door, bounding like jackrabbits, to the playing field where we would emulate the champions. We played past sundown, playing our brains out, in the dark—Who has the ball!

I’m equally hopeless whenever I read Virginia Woolf. I rush to my manuscript and emulate the hell out of her. I wrote the 15th draft of my novel ROXY in an adrenaline rush after reading Mrs. Dalloway.

What a joy to write like a lover. We’re not mechanics. Mechanics think. Lovers love their characters ecstatically and to death.

#3. Love your characters to death

There’s nothing “how-to” about this dictum, because no one else can tell you how to love your protagonist to death. You invented him and only you know how to thwart him. But you have to do it, the hero must die. Just do it. It is (arguably) all that counts in fiction. There’s no “how-to” book out there that teaches you how to love your fictional characters to death.

To heck with “how-to”—what about “where to”?

#4. Forget “how-to” in favour of “where-to”

What’s the point of “how to” if we don’t understand “where to”? We wouldn’t buy an appliance without knowing what it’s for. So, what’s fiction for? What’s at the heart of fiction? Is that where it’s going? What’s it all about?

Reading the best fiction we learn (repeatedly) that the best protagonists are on a trajectory toward freedom from their lesser selves. That’s “where to.” That’s (arguably) all we need to know. We keep writing draft after draft until our protagonist has arrived. We know he’s there when he stops kicking and screaming. He’s got that far away look in his eye. He’s gone so far and is so disillusioned with his game plan that he has no alternative but to forsake himself. A higher cause descends. There’s no “how-to” about it. This may look like “how-to,” but it’s not. It’s about understanding the human condition.

#5. Don’t try to BE a writer

“How-to” tomes often coax us to be a writer rather than encourage us to do the hard work that would turn us into writers. That is to say, write your brains out. I’ll bet there are young writers out there reading less literature than “how-to” books. We’re being seduced into posing as writers “rather than spending the time to absorb what is there in the vast riches of the world’s literature, and then crafting one’s own voice out of the myriad of voices.” (author, Richard Bausch)

#6. Don’t get it right, get it written

I sometimes run a course with such a title. Students write at home, then come to class to watch scenes from powerful movies—scenes that give the audience their money’s worth. And by that I mean scenes that depict the hero challenging his own human condition. Challenging the right of his own beliefs to prevent his true happiness.

Immersing ourselves in fiction, we get a feel for a story’s essential payoff. We are astonished each time we recognize it. And then we constructively and lovingly critique each other’s work before bolting for home like jackrabbits.

#7. Write your own “how-to” book

Make notes on your own astonishment at how the best writers serve the art of fiction. Each of our understandings is bound to be unique. Your perspective is going to underpin your own advice about “how-to.” Write that book and put it on the shelf and let it breathe down your neck.

Go for it, Claudia of Argentina. Write your own manual out of love for writing.

Our own “how-to” will be born of the love of the art of fiction.

Join Leslie Helakoski and Darcy Pattison in Honesdale PA for a spring workshop, April 23-26, 2015. Full info

here.

COMMENTS FROM THE 2014 WORKSHOP:

- "This conference was great! A perfect mix of learning and practicing our craft."�Peggy Campbell-Rush, 2014 attendee, Washington, NJ

- "Darcy and Leslie were extremely accessible for advice, critique and casual conversation."�Perri Hogan, 2014 attendee, Syracuse,NY

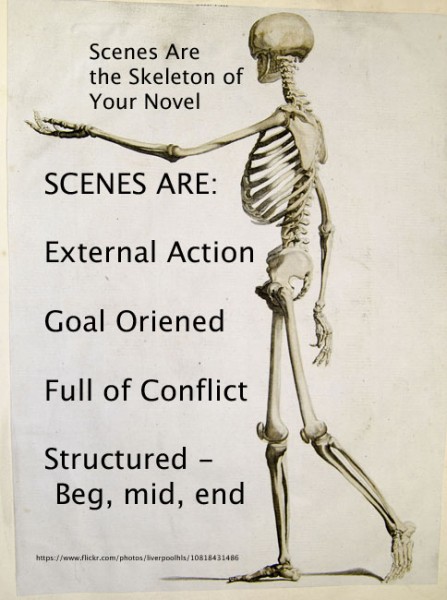

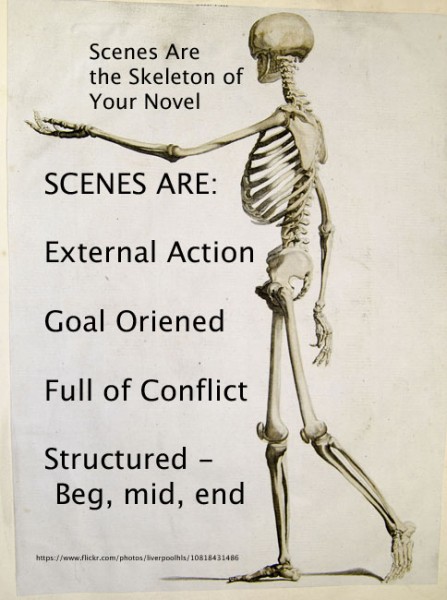

You’re a human being: you can stand up, sit down, or do a somersault. That’s because you have a skeleton that gives your soft tissue a structure.

Likewise, it’s important to give your novel a structure that will hold all the soft murmurings about characters, places and events. It begins with understanding the structure of a scene. First, let’s answer the question: do you have to write in scenes? No. There’s a continuum from those who write strictly in scenes to those who don’t. However, for beginning to intermediate writers, you’ll see more improvement in your writing if you move closer to the strictly writing in scenes end of that continuum. Early in a career, writers need discipline to add structure that may come more easily with experience.

External Action. A scene is a unit or section of a story that hangs together because of the action or event. Scenes are not internal, but external. Something must physically happen.

Something Changes. Something important must happen in a scene; after the scene is over, the situation must be different for the character’s lives. The definition of “important” and “different,” of course, will change with the genre, but still, we recognize that something important has created a difference.

Goal Oriented. The strongest scenes begin with a character wanting something and encountering difficulties in achieving his/her goal. The goal can change or develop over the course of a story, but it must be there.

Conflict. If your character wants something (Goal), and they have instant gratification (Result), that’s not a scene. Every Goal must meet with obstacles that prevent the character from achieving the goal. This is the basic promise of all fiction, that life will encounter problems that won’t be solved till the last page.

Beyond these requirement, strong scenes add a deeper structure. It’s not required, for those who only write loosely in scenes, but it helps.

Scenes can be divided into three or four sections: beginning, middle, turning point or pivot, ending.

Beginning: This sets up the situation, setting, characters and the goal.

Middle: Conflict piles on conflict as the goal gets farther and farther away.

Turning point/Pivot: Something happens to spin the story in a different direction. Scenes without a pivot are possible, but scenes WITH a pivot are more interesting.

Ending: What has changed?

Good Will Hunting: Bar Scene Analyzed

A good way to see the structure of a scene is to watch the “Bar Scene” from the movie, Good Will Hunting. If you can’t see this video, click here.

Beginning: Will and his friends enter the bar, choose a table, order a beer.

Goal: These “Southies” want to experience a Harvard Bar and maybe pick up a girl.

Middle: Chuckie goes over to check out a girl. But a Harvard man steps in to put him down.

Pivot point: Will takes over the conversation with his superior intellect.

Ending: Will meets the love interest. The conversation with the Harvard man is a win/lose: Will wins because he manages to make his point that a college education isn’t everything; however, listen carefully to the deeper conversation about class distinctions and you’ll see that Will still faces challenges.

For more on scenes, I always recommend Sandra Scofield’s excellent book, The Scene Primer. Or see my series, 30 Days to a Stronger Series.

Join Leslie Helakoski and Darcy Pattison in Honesdale PA for a spring workshop, April 23-26, 2015. Full info

here.

COMMENTS FROM THE 2014 WORKSHOP:

- "This conference was great! A perfect mix of learning and practicing our craft."�Peggy Campbell-Rush, 2014 attendee, Washington, NJ

- "Darcy and Leslie were extremely accessible for advice, critique and casual conversation."�Perri Hogan, 2014 attendee, Syracuse,NY

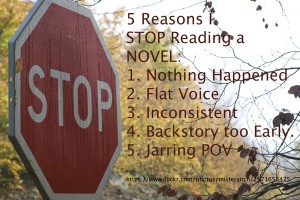

Openings are incredibly important. This was brought back to me recently as I was judging a contest. Those manuscripts that kept my interest for three pages were rare. Usually, they lost me by the middle of page two!

Am I harsh? I don’t think so.

Grab the Reader with Your Opening Lines

Noah Lukeman has it right in his book, The First Five Pages: A Writer’s Guide to Staying Out of the Rejection Pile. This is a book I ask those attending my Novel Revision retreats to read before they attend. Lukeman’s premise is that an editor will decide if they want your book or not based on the first five pages of your manuscript. After judging this contest, I agree. Sometimes, you can even make a judgment based on the first paragraph.

That first paragraph? You want to grab the reader by the throat and never let go!

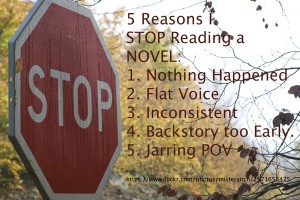

Here are five things that made me stop reading

- Nothing happened. The whole first chapter could be cut, because no major action occurred. Ask yourself: what happened in this chapter? Is there any conflict here?

-

The voice was flat. Monotone and uninteresting. Read it aloud: Does the text demand that you use an interesting variation of pitches, tones, stops, starts, etc?

- Inconsistencies. If I found myself thinking, “No, that couldn’t happen. Not that way,” then the story was in trouble. Consider: does the story logic work?

- Backstory. Please don’t put backstory in the first chapter. Give us an active scene with the character in motion and wanting something. It doesn’t have to be the major goal of the book, but the character needs to want something and it should be something that leads into the main conflict. Ask yourself: Do I really need to explain the backstory here, or can I wait until page 100? Yes! Page 100! Move that stuff out of the first act entirely!

- The point-of-view jumps out at me. Too many of the mss had first-person point-of-views that just jumped out at me and made me cringe. In other words, the voice wasn’t distinctive enough for first person. This is a personal opinion–FWIW–but I think too many people are trying to write a first-person narrative. The default should be third-person unless there is a compelling reason for first. It’s not just a bias against first-person, but rather, that the story would be better served from third in many cases.

There were some first-person stories where I didn’t even realize it because the story caught me. When it works, it work well. When it fails, the story might could be salvaged by a switch to third. Consider: Is there a compelling reason for the first-person point-of-view? Could this ONLY be told from first? Try–OK, just try–writing the first chapter from third and give it to an independent, unbiased reader (like you can find that!) and ask which version they like better (don’t tell them what the difference is). I bet that third will win in the majority of cases.

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course: ON DEMAND

I am a failure.

I signed up for NaNoWriMo–again. And again–I failed to make 50,000 words.

But I have good reasons.

World Building. I did massive work this month on world building. Since I’m writing a science fiction novel, I needed to invent technology, figure out where to locate installations, design the installations to meet the needs of my sff characters and the needs of the story, create scientifically accurate details throughout, along with the usual backstory.

I used Google Earth to investigate Mt. Rainier and the surrounding area, worked on backstory and characterization, and dug into the details of scenes. Many scenes that are still to be written have been written about; that is, I’ve written notes about who, what, when, where, why and with what emotion. When I do sit down to write the scene, it should go quickly.

November is Hard. I’ve never understood the decision to make November the NaNoWriMo month; it’s one of the busiest months for me. Arkansas has a major reading conference, besides the Thanksgiving holiday. All together there were 7-8 days I simply could not write because I was busy all day with other activities. For me, burning the midnight oil does no good, but at that hour, all I can write is crap. Still, I wrote steadily on the days that I could and made progress.

Writing Style. Fashion swings wildly. Many editors believe that writing should take a long, long time. The fad in the Indie world these days is very rapid writing. In the end–I write as fast as I can and still turn out something that pleases me. I must please myself, not an editor or a contest like NaNoWriMo or anyone else. I can only write as fast as I can write.

My Speed is OK

It’s really OK that I didn’t write 50,000 words this month.

It’s really OK that I didn’t write 50,000 words this month.

- I had a great time at the Arkansas Reading Association conference.

- I had a great time with my family.

- I wrote about 32,500 words, which is 32,500 words more than I started the month with. More than that, I know my characters better and know that it was a very good month of work.

That’s all I can say.

.jpeg?picon=3304)

By: Leslie Ann Clark,

on 11/20/2014

Blog:

Leslie Ann Clark's Skye Blue Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Illustrator,

children's books,

work,

kids,

creativity,

visual,

imagination,

cartoons,

Children's literature,

ideas,

beaver,

Bear,

how to write,

log cabin,

My Characters,

Add a tag

Being an illustrator is great fun. Why? Because you can use your imagination to go places you’ve never been and do things you’ve never done. For instance, I have always wanted a log cabin up in the mountains. As a teen, I used to imagine having a studio up a flight of wooden steps to a big room. It would have rafter ceilings and a window seat for me to look out of. It would be warm and cozy and I could sit and do my art all day long near a roaring fire in the wood stove.

When I began thinking of places for my character Burl the bear to live in, I made it just like “I” wanted it! Warm and inviting! When you walk through the doorway of my story, you will find a home that lives in my imagination. It will be a place that I love and I will revisit it many times as the story progresses. I must be passionate about what I draw or it becomes listless and boring. This process is what makes a story believable.

My experience tells me that children notice the tiniest of details. I did a school visit after Peepsqueak was published by Harper Collins Publisher. I read the book to the children and then we talked. Through out the story there was another story going on in the book. It was a little tiny mouse who appeared on many of the pages. The children did not miss it. They even commented on the mouse as I read to them. I let them in on a little secret. I named the mouse Elliot. When I told them his name they all squealed with delight and pointed to the cutest little boy in their classroom who was named Elliot! He was beaming. Suddenly he became part of the story. He was so happy!

These are the things that make a story magical in the eyes of children and adults alike. Its also why I continue creating images. I love seeing characters develop. I love finding their voices. .. what they are like… what they like to do. It does not stop when I leave the studio. I think about them all the time, until I finally know how they would react in any given situation. That way they become very believable creations and loved by all.

Stay posted, Burl and Briley are growing on my heart daily. I can hardly wait to illustrate the books that are in my mind!

Filed under:

how to write,

My Characters

A lot of people are doing NaNoWriMo this month (for those who don’t know it, the aim is to write 50,000 words of a novel in November) so if anyone’s feeling a bit stuck, I thought I’d share a variation of a technique I used in a masterclass at CYA in July.

Now that I've discovered it, I intend to use frequently during the progress of a manuscript, but I think it’s useful early on - when you’ve thought about your characters quite a lot already, and you thought you knew the shape of the story, but now that you’re writing it, nothing’s quite as sharp and clear as you thought it was.

It can be challenging, but it works well – and remember, nobody’s watching or judging.

So: get a paper and pencil, or a sharpie, and just ask your protagonist, ‘What do you most want?’

But the trick is: you write the question out with your dominant hand, and answer with your non dominant hand – that’s why a nice fat sharpie is good. Don’t think about the answer, just let it come, misshaped letters and all. I've only used it for child characters so far, but I think it's also valid for adult protagonists, because most of our deepest wants and fears come from the child within us.

If your character doesn’t know what they want, ask what they’re most afraid of. Ask why. Ask whatever you think a probing counsellor might ask them. And most importantly, don’t judge their answers. You might be surprised at what comes – I usually am.

And whether you use all that you’ve discovered or not, you’ll certainly end up with a stronger feeling of who your character is. Just don’t forget that you’re still the boss, so you may not choose to give your character exactly what they think they want. But it may give you a clearer idea of what they need to experience, and therefore, where you want your story to go.

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video course

Writing teacher Darcy Pattison teachers an online video course, 30 Days to a Stronger Novel. Each day includes an inspirational quote, and tips and techniques for revising your novel. Here are the 10 of the inspirational quotes.

Or sign up for more information on the availability of this course and other courses.

The titles below are the first ten entries of the Table of Contents for the Online Video Class. Sign up now for the Early Bird list. You’ll be notified when the course goes live.

-

The Wide, Bright Lands: Theme Affects Setting

-

Raccoons, Owls, and Billy Goats: Theme Affects Characters

-

Side Trips: Choosing Subplots

-

Of Parties, Solos, and Friendships: Knitting Subplots Together

-

Feedback: Types of Critiquers

-

Feedback: What You Need from Readers

-

Stay the Course

-

Please Yourself First

-

The Best Job I Know to Do

-

Live. Read. Write.

30 Days to a Stronger Novel Online Video Course

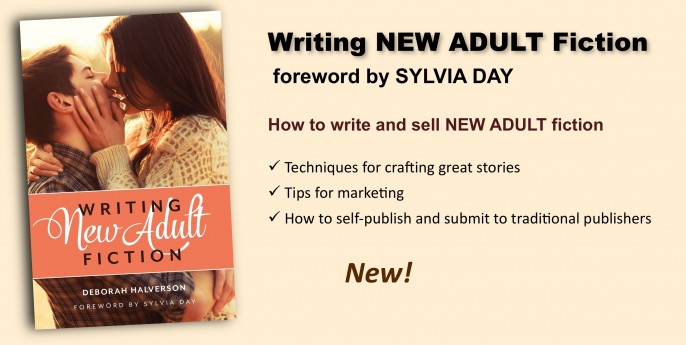

In the immortal words of Charlotte in E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, “It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer.”

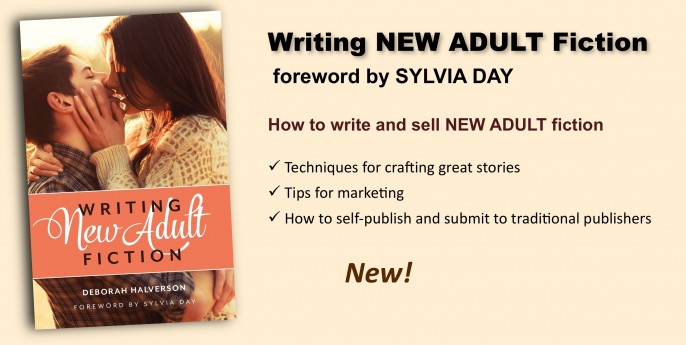

I was privileged to have Deborah Halverson edit my Harcourt picture book, Searching for Oliver K. Woodman. When we met at a retreat, it was instant friendship, and anytime we talk, it feels like we’ve been friends forever. That’s why I am so excited about this new book. Well, I’m excited because it’s Deborah’s book, but also because it’s the first book I’ve seen to explain the latest fiction genre, New Adult. In Deborah’s capable hands, the topic comes alive and I’ve already got tons of ideas for stories. Here, she answers a basic question; but if you want more, you’ve got to buy her book!

Guest post by Deborah Halverson

Guest post by Deborah Halverson

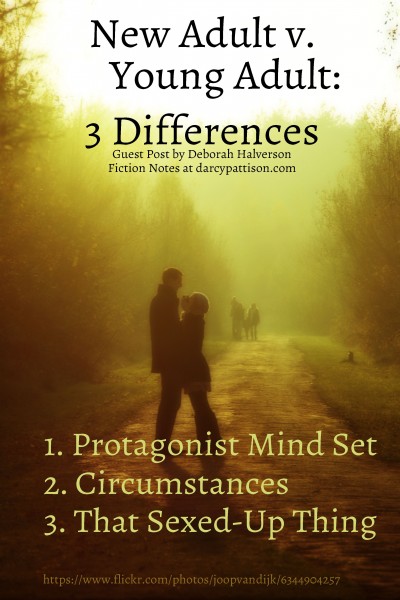

YA writers often ask me to explain the difference between Young Adult fiction and New Adult fiction when the story’s main character is 18 or 19 years old. Some of those writers are curious about this new fiction category that brushes up against their own, but others are trying to noodle out whether that upper YA story they’re working on is really NA. “Tell me what NA is, Deborah, and then I’ll know what I’ve got.” Happy to help! Here are three ways to determine if you’re writing a story about a young adult or a new adult.

DearEditor.com Deborah Halverson is doing a special giveaway for the blog tour for the kickoff of this book. Enter to win “One Free Full Manuscript Edit!“

Pin Down Your Protagonist’s Mind-set

How does your character process the world and her place in it? Teens are typically starting to look outward as they try to find their places in the world and realize that their actions have consequences in the grander scheme of life, and they yearn to live unfettered by the rules, structure, and identities that have defined their lives until now. New adults finally get to live that free life they dreamed of—for better or worse. They move forward with the self-exploration they began in their adolescence, going big on personal exploration and experimentation and expanding their worldview. They get to build identities that reflect who they’ve become rather than who they grew up with, and they get to try things out before settling into a final Life Plan. All of this can be overwhelming even when it goes well—after all, even good change is stressful, and “change” is new adulthood in a nutshell. For some, though, the instability is a total freak-out. The clash of ideal vs. reality can shock their system. They’re gaining experience and wisdom hand over fist, but yikes. Luckily, new adults tend to brim with personal optimism, and their explorations and experimentations—both dangerous and beneficial—are endearingly earnest.

If this sounds like your protagonist and her circle of friends, you might have an NA on your hands. You can use this knowledge to give your story a solidly NA sensibility by exposing your character’s inexperience in her decision-making, by imbuing the narrative with a sense of defiance, by conveying stress, by conveying self-focus (not selfishness), by lacing the exposition with personal optimism, and by showing the character’s awareness of her growing maturity. YA characters who are overly analytical about themselves and others risk sounding too mature, but NA character journeys ooze with self-assessment no matter the individual details of their journeys.

Assess Your Circumstances

In fiction, the plot exists to push the protagonist through some kind of personal growth. Thus, our character’s mind-set and the plot are interdependent. Whether your character is a young adult or new adult, the circumstances of your story—the events, problems, places, and roles—should sync with that character. New adults tackle their problems with their new adult filters in place, whether the story is a contemporary one set in college, or a historical one, or a fantastical one. Self-actualization is an essential growth process whether you’re at a college kegger or battling evil overlords.

In fiction, the plot exists to push the protagonist through some kind of personal growth. Thus, our character’s mind-set and the plot are interdependent. Whether your character is a young adult or new adult, the circumstances of your story—the events, problems, places, and roles—should sync with that character. New adults tackle their problems with their new adult filters in place, whether the story is a contemporary one set in college, or a historical one, or a fantastical one. Self-actualization is an essential growth process whether you’re at a college kegger or battling evil overlords.

Once you’ve pinpointed whether your protagonist’s mindset feels YA or NA, consider if your plot events and the circumstances of your protagonist’s life jive with her concerns, fears, coping skills, maturity, and wisdom level. NA story lines tend to remove structure and accountability, tweak the characters’ stress levels by playing musical careers and homes, make money an issue, force the characters to establish new social circles at play and at work, show characters exhibiting ambivalence to adult responsibilities, show characters divorcing from teenhood, show characters striving to “move on from trauma” rather than to “survive trauma”, deny the characters the “ideal” NA life of carefree self-indulgence, put characters in situations that clash their high expectations for independent life against a harsh reality, and show the process of evaluation, of trial-and-error, of weighing exploration and experimentation against consequences, at least by the end of the story.

Deal with the “Sexed-Up YA” Thing

Romance is part of almost any older YA story, and certainly all NA. As it should be—romance is one of the three main areas of identity exploration after puberty, along with career and worldview (think politics, faith, and personal well-being and outlook). The difference is that teens are very solidly in the “what is love, what does it feel like?” realm, whereas new adults are generally working on who they want to be in a relationship, what they want from their partner, what they want from the relationship in general. That doesn’t mean they’re actively searching for Mr./Mrs. Right—there’s plenty of time for that!—but it does mean they want a satisfying, meaningful relationship. Where is your character on that romance spectrum?

Of course, romance isn’t really what people focus on when comparing YA and NA relationships, is it? Nope: it’s sex. So let’s talk about sex. In its early days, NA was accused of being “sexed-up YA”, but after reviewing numbers 1 and 2 above, you’ll see that the differences between YA and NA are more substantial than simply how explicitly you describe two bodies connecting sans clothing. Ask yourself your goal with the romance, and what level of sexual detail is necessary for that goal. Then consider your audience: NA readers are mostly adults of the same 20- to 44-year-old “crossover reader” demographic that shot YA into the publishing stratosphere. (A Digital Book World study reported 2013’s dominant YA crossover readership as being 20- to 29-year-olds; compare that to the 18- to 25-year-old age range of new adulthood). Those grownups can handle—and often flat-out want—explicit sex scenes. Some teens will read NA, but mostly they’re not into that mind-set yet so the stories don’t resonate with them, making them plenty happy to stick with the many great YA stories out there that reflect their current time in life.

Perhaps you determine that your character’s mind-set and story circumstances are solidly YA but you want/need to include some sex scenes in your story because the theme or plot of the story calls for it. In that case, maybe you have a solid YA that requires a “Mature YA” categorization to let readers know that there’s sexual content between those covers. Those scenes will be tamer than the full-on explicitness of NA—your are writing/positioning this story primarily for and about young readers after all, and there are gatekeepers involved—but the sexual content is there and readers are warned. Weigh your goals with your romance, your story’s scene needs, and your audience’s expectations and sensibilities as you make the NA/YA determination on this aspect of your WIP.

So there you have it. Three ways to know if that story you’re writing is Young Adult fiction or New Adult fiction. Good luck with your WIP, and with all your publishing endeavors.

Deborah Halverson is a veteran editor and the award-winning author of

Writing Young Adult Fiction For Dummies. Her latest book, Writing New Adult Fiction, teaches techniques and strategies for crafting the new adult mindset and experience into riveting NA fiction. Deborah was an editor at Harcourt Children’s Books for ten years and is now a freelance editor, the founder of the popular writers’ advice website

DearEditor.com, and the author of numerous books for young readers, including the teen novels

Honk If You Hate Me and

Big Mouth with Delacorte/Random House. For more about Deborah, visit

DeborahHalverson.com or

DearEditor.com.

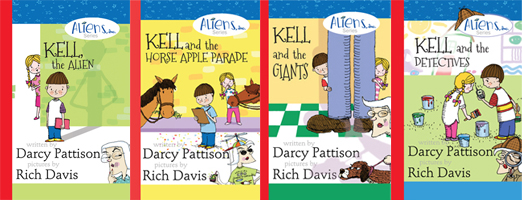

The ALIENS have landed!

"amusing. . .engaging, accessible," says Publisher's Weekly

|

|

|

To write a series of books, my biggest tip is to plan ahead. You may get by with writing one book on the fly—plenty of people do that. But for a series to hang together, to have cohesion and coherence, planning is essential. Here are three decisions you should make early in the planning process.

Decision #1: What type of series will you write?

Strategies for a series vary widely. For THE HUNGER GAMES, the story is really one large story broken down into several books. Or, to say it another way, there is a narrative arc that spans the whole series. Yes, each book has a narrative arc and ends on a satisfying note; however, we read the next book because we want to know what happens in the overall series arc. Jim Butcher’s ALERA CODEX is another series with an overall series arc; it was fun to hang out in this world for a long time.

On the other hand, series such as Agatha Christie mysteries (in fact, many mystery series fall into this category) are stand-alone books. What continues from one book to the next is the characters, the setting and milieu, and the general voice and tone of the stories. Once a reader gets to know a character, s/he wants to spend more time with that character. These readers just want to hang out with a friend, your character. A sub-category is the series of standalone books that adds a final chapter to set up the next book in the series and leaves you with a cliff-hanger.

I distinctly remember when I first read Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter series about Mars. Each story is a standalone novel, but he hooked me hard. I started reading at noon on a Saturday and found myself hotfooting it to the bookstore at 4:30 pm because they closed at 5 pm and I had to have the second book to read immediately.

Rarer is the series that crosses genres. This type series begins with one genre, but moves into other genres as the lives of the characters progress. For example, a romance might continue with a mystery for the second book. And the third might move into a supernatural genre. These are rarer because one reason a reader sticks with a series is that they know what they are getting. It will be this type of a story, told in this sort of way and will involve these characters.

On the other hand, some series unabashedly cross genres but they do it for every book. Rick Riordian’s Percy Jackson series is a combination of mythology and action/thriller with a dose of mystery.

Notice that this decision centers on the plot of the stories in the series. Will you plot each separately, or will there be an overall plot?

Decision #2: Characters

Besides plot, you should make decisions about characters, and as with plot, you have choices. One choice is an ensemble cast that will carry over from book to book. Here, you have Percy Jackson, his friends and his family as constants. Each book introduces new characters, of course, but there is a core that stays the same.

Another option is to have just one character remain the same. Agatha Christie had Hercule Poirot traveling around and the only constant was the gumshoe and his skills.

Whether you choose one character or an ensemble, you can add or subtract as you go along. But the characters must be integral to the story’s plot.

In developing series characters, think about cohesion and coherence.

Cohesion: Elements of the story stick together, giving cohesion. For example, if one alien in the family can use telekinesis (moving objects with your mind), then that possibility should exist for all members of the family. Of course, some might not have the power, or it may develop slowly for a child, but the possibility should exist.

Coherence: Elements of a story are consistent from book to book. If Kell’s eyes are silvery in book one, they are silvery in books two, three and four.

Decision #3: How long do you want the series to continue?

Many easy readers series go on forever. Think of THE BERENSTAIN BEARS, who continue their adventures and lives throughout multiple volumes. For this type series, the story possibilities are endless. Or think of a TV series, where the situation set up is rich with possibilities. I Love Lucy ran for years and years on the premise of a slightly crazy wife of a musician.

On the other hand, some series have a finite life span. For stories with a narrative arc that spans a series, the life span is built into the plot. However even for these, there can be spin-offs into related series. Think of Percy Jackson and the Olympians series and Heroes of Olympia series. The A to Z Mysteries by Ron Roy and John Gurney had a built-in limit of 26 books.

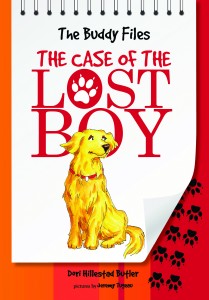

The Buddy Files Series, Book 1, by Dori Hillestad Butler

Sometimes, the length of a series depends on the publisher and the early success of the series titles. When Dori Hillestad Butler’s first book in

The Buddy Files series, THE CASE OF THE LOST BOY, won the 2011 Edgar Award for the best juvenile mystery of the year, the publisher contracted for more.

For Sara Pennypacker, author of the CLEMENTINE series of short chapter books, the answer of series length depended on something else. In a presentation about writing, she said that she had to ask herself what she wanted to say to third graders. She came up with eight things. Pennypacker focused on the themes of each book (friendship, telling the truth, etc) and found that eight was the natural stopping place for her. Of course, she reserves the right to many more, if other themes present themselves. But she deliberately stepped away from doing a Christmas book, a Halloween book, a 4th of July book, a fall book, a back-to-school book and so on and so forth.

My books, THE ALIENS, INC. SERIES, just released in August, 2014, is about an alien family that is shipwrecked on Earth and must figure out how to make a living. It’s been interesting developing these stories and thinking about these three issues.

My books, THE ALIENS, INC. SERIES, just released in August, 2014, is about an alien family that is shipwrecked on Earth and must figure out how to make a living. It’s been interesting developing these stories and thinking about these three issues.

They accidentally fall into party planning and each book features a different type of party or event put on by Aliens, Inc, the family’s company. KELL, THE ALIEN, the lead-off story, is about a birthday party and of course, it is an alien party. Can the aliens pull off an alien party? The second is about a Friends of Police parade, entitled, KELL AND THE HORSE APPLE PARADE. Book 3, KELL AND THE GIANTS, explored the world of tall and how to keep a giant secret.

Can you tell just from the description some of the decisions I made? There isn’t an overall series arc. Rather, the characters, setting and milieu are set up and there could be endless stories in the series. However, like Butler’s dog mystery series, I am starting with four books and their success will determine future titles. There is a main character who is surrounded by friends and family and, of course, a villainess. These characters weave through the stories and provide cohesion and coherence.

Plan ahead and your series will be stronger. For those who accidentally fall into a series, it will be harder to sustain coherence. You may realize in book three that it sure would be nice if your character had to wear glasses. Yes, you can add it—but you run the danger of it being obviously done for the story itself. So, in my series, early readers have questioned things like the art teacher who is from Australia.

They ask, “Does it matter that she is from Australia?”

“Not yet,” I answer. I just know that I have seeded these early manuscripts with possibilities. If the series goes to books 5-8, I will have hooks to draw upon. So, while I haven’t plotted those books, I have still allowed room for them.

Resource: Writing the Fiction Series: The Complete Guide for Novels and Novellas by Karen S. Wiesner (Writer’s Digest Books)

Want to write a series? What is your favorite series and how will your stories compare?

More than one local prolific author has said she read hundreds of books in her genre before writing her own well. Hundreds. Good books, bad books, but all in the genre in which she intended to write.

I think this is possibly the best course one could take for writing. And you'd be surprised how many people I know want to write in a genre that they don't actually read: people with a picture book idea who think if they throw some rhyming words together it is publishable without ever cracking a published picture book, people who read nonfiction but want to write dystopian YA, people who only read romance but want to write memoir.

It's normal to be in love with our own ideas. They are our babies, after all. But if we are going to send them out into the world, we have to know what their place in the world could be. And to do that, we have to know something about their peers. (It also helps with writing the dreaded queries ... a topic I'll discuss on my next post.)

So I want to pass on this advice: read in your genre. Read a lot in your genre. Yes, hundreds of books. Okay, start with 20 and build. But make a serious goal.

But when you read, read like a writer.

Reading like a reader is passive, it is as simple as deciding if you "like" or "don't like" a book.

To read like a writer is to question and answer exactly what it is that is and isn't working. In fact, finding a book that you don't like can be of more value than digging into a book that you love. When we love a book, we are taken by it in a visceral, emotional way. It becomes "ours" in a way that our own writing is "ours." It is hard to be critical of your darlings.

On the other hand, good old favorites—the ones you've read over and over, the ones that you feel you already know—can be useful to look at closely because you aren't getting caught up in the plot. You know it well enough to lift the curtain and see what is underneath each page.

When you are reading hundreds, though, you are bound to find those that you don't like. Those can be easier to take apart. Because the undeniable fact is that this book made it. So you have to figure out what it is about the book—the language, the construction, the story, the setting, the dialogue, the characters—that managed to get it passed the gauntlet of queries, slush piles, agents, publishers, and book stores to find its place on this shelf (be it physical or digital).

So, break it down.

Really understand the construction of the book. Think of it as a scaffolding upon which the words hang. Even in a picture book—the most compact of stories—plot is carefully built like the frame of a building. It must be solid and balanced. Writers are engineers. Read like an engineer.

Carefully note dialogue that moves you and dialogue that seems unnecessary. Then figure out why that is. The "why" isn't always that easy to decipher. It may be the language, or it may be the setting in which the dialogue takes place. Also look at the balance of dialogue to exposition. When does the description of a movement from a character "say" more than dialogue? How is it done?

Are there single, carefully chosen words that tell more about the setting than a lengthy description?

Whatever it is you want to learn, you can learn a lot about it by the careful reading of many examples. The more, the better. Say, one hundred.

How long will you take to read one hundred ... like a writer?

An aid to smart revising based on Darcy Pattison’s techniques

Guest Post by

Claudia Finseth

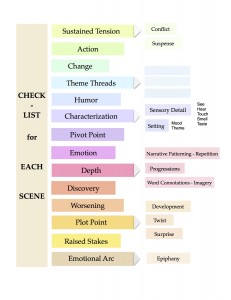

I recently took Darcy’s Whole Novel Workshop and read her book, Novel Metamorphosis: Uncommon Ways to Revise. Between the two, there was a great deal of valuable new information to process. I’m very visual, so one way I worked through and organized the information was by creating charts. To what are mostly Darcy’s ideas, I added a few of my own, and some I’ve learned in other workshops. Darcy has asked me to share these charts here on her blog.

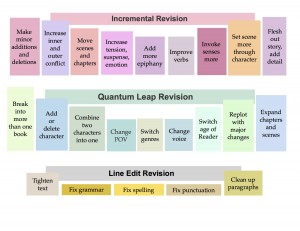

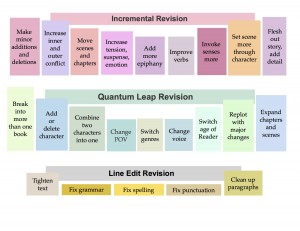

The first chart is The Novel Revision Chart. As Darcy teaches, there are many types of revision to consider once we have a draft of a novel.

This Novel Revision Chart show the different types of revisions and helps you prioritize the revision tasks. CLICK TO VIEW FULL SIZE.

Darcy’s workshops are based on critique groups. Participants work in groups of four, reading and commenting on each other’s manuscripts and. Taking the three critiques of my novel, I made a list of all the types of revision my group suggested for my novel: not letting the tension flag, pulling all my theme threads all the way through the novel, keeping my character age-appropriate, etc.

Attend a Novel Revision Retreat

The Darcy Pattison Novel Revision Retreat will come to the Boston area in August, 2014. There are a limited number of spaces still available. See Anne Broyles site for details. Also available is a Build Your Website session and a Picture Book Workshop. Hurry! Spaces limited! And time is short!

Then, I identified where these types of revision landed on the Novel Revision Chart. If they landed somewhere on the Incremental Revision line, I figured I could work with what I had already written. The three types of revision mentioned in the previous paragraph all land there. If, however, the needed revisions landed on the Quantum Leap Revision line, then I figured maybe I should scrap this chapter or that and write it again from scratch. Or write the whole novel again in a new draft. Or take the novel apart and reorganize it in some major way. For instance, my second novel is probably really three novels. (Sigh.) But better I realize that now than waste time trying to fix it the way it is.

The point is, this chart can help writers identify how major or minor the next revision needs to be, as well as what kind of revision needs to be focused on next. It can save us spinning our wheels on the wrong kind of revision. How many times have we worked on verbs or sensory detail when what we needed was to introduce another character or change the beginning? Trust me: been there, done that, and it’s very annoying to realize I should have been working on a totally different kind of revision. The chart can make us smarter revisers.

The Line Edit Revision part of the chart is a reminder that the final revisions you do, once the novel is firmly shaped and sparkling with life, and just before submission, need to be these five types of micro-edits. Therefore, it is at the bottom of the chart.

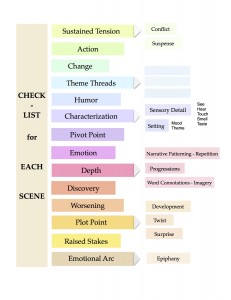

Checklist for Revising Scenes.

But before we do any line editing, there’s the second chart to look at, A Checklist for Each Scene. As the first chart is a way of evaluating the revision needed overall, this second chart is for scene by scene revisions. As Darcy explains in Novel Metamorphosis: Uncommon Ways to Revise, each scene is a kind of whole of its own. Taking one scene at a time, a writer can use this chart in conjunction with Darcy’s book to make sure each scene includes all the elements required to create a tight, compelling scene that propels the reader into the next one.

After the major revisions and before the minor Line Edit revisions, you should do a scene check. CLICK TO SEE FULL SIZE.

I have these charts before me as I work. They are quick reminders of each step needed to flesh out and deepen a scene and ultimately write a novel that editors will want to publish because they are so rich and satisfying a read. I’ll make checks on the charts as I go, when I think I’ve accomplished each type of revision. And when I’m “done” I’ll put a big exclamation mark in sharpie marker, or a smiley face, or perhaps I’ll save them for the next novel.

Claudia Finseth is a writer and author living in Tacoma, Washington. She is published in non- fiction adult, poetry and short children’s stories in Cricket Magazine. Her goal now is to become an adept at the novel form. “Novels are hard!” she says. Her website is

claudia.finseth.ca.

Today, I stare failure in the face.

Today, I am scared.

Today, I see possibilities as the possibility of failing.

In other words, I have finished all my self-imposed deadlines on other projects and cleared my plate of other tasks, so that I can start a new novel. And it terrifies me.

It’s an ambitious project, something I expect to turn into a trilogy. I have such hopes for this project: hopes that it will reach new readers; hopes that it will be fun to write and promote; hopes that it will be (I’m afraid to even say it!) a breakout novel for me.

And I am scared.

I’ve done my homework. Volcanoes feature large in this story, so last month while I was in the Pacific Northwest, I visited Mt. St. Helens.

I recently visited Mt. St. Helens for research on the background for a new novel.

I’ve written samples for this story from different points of view, and even sold a short story based on the back story.

And yet–I am scared to sit down and start this. Yes, I’ve written the book on starting a novel and I’m still scared to start again. As ART AND FEAR puts it, I am scared that my fate is in my own hands–and that my hands are weak.

I SHOULD see the great possibilities of success.

I SHOULD approach this with excitement.

I SHOULD be so ramped up by now that the words would flow, as if bestowed from above, with angelic music swelling and…

No. Writing is work. It’s the hardest work I’ve ever done or ever hope to do. But it’s also the most exciting, most fun, and most rewarding work I will ever do.

So, at 8:30 this morning, I’ll turn on my Freedom app, giving myself three hours of uninterrupted time. I will make a start. A messy start. But a start. And that will be enough for today. Just make a start, that’s my goal for today.

.

Choosing the right set of words–the diction of your novel–is crucial, especially in the opening pages of your novel. Novels are a context for making choices, and within that context, some words make sense and some don’t.