Technology is changing. The climate is changing. Economic inequality is growing. These issues dominate much public debate and shape policy discussions from local city council meetings to the United Nations. Can we tackle them, or are the issues divisive enough that they’ll eventually get the better of us? In terms of global poverty, economist Marcelo Giugale believes that human beings have the resources and will to overcome the dire state of circumstances under which many people live. In this excerpt from his latest book, Economic Development: What Everyone Needs to Know, Giugale asserts that humans have the means to quash abject poverty on a global scale and make it a thing of the past.

Define poverty as living with two dollars a day or less. Now imagine that governments could put those two dollars and one cent in every poor person’s pocket with little effort and minimal waste. Poverty is finished. Of course, things are more complicated than that. But you get a sense of where modern social policy is going—and what will soon be possible.

Nancy Lindborg trip to South Sudan. USAID U.S. Agency for International Development. CC BY-NC 2.0 via USAID Flickr.

To start with, there is a budding consensus—amply corroborated by the 2008–9 global crisis—on what reduces poverty: it is the combination of fast and sustained economic growth (more jobs), stable consumer prices (no inflation), and targeted redistribution (subsidies only to the poor). On those three fronts, developing countries are beginning to make real progress.

So, where will poverty fighters focus next? First, on better jobs. What matters to reduce poverty is not just jobs, but how productive that employment is. This highlights the need for a broad agenda of reforms to make an economy more competitive. It also points toward something much closer to the individual: skills, both cognitive (e.g., critical thinking or communication ability) and non-cognitive (e.g., attitude toward newness or sense of responsibility).

Second, poverty fighters will target projects that augment human opportunity. As will be explained next, it is now possible to measure how important personal circumstances—like skin color, birthplace, or gender—are in a child’s probability of accessing the services—like education, clean water, or the Internet—necessary to succeed in life. That measure, called the Human Opportunity Index, has opened the door for policymakers to focus not just on giving everybody the same rewards but also the same chances, not just on equality but on equity. A few countries, mostly in Latin America, now evaluate existing social programs, and design new ones, with equality of opportunity in mind. Others will follow.

And third, greater focus will be put on lowering social risk and enhancing social protection. A few quarters of recession, a sudden inflationary spike, or a natural disaster, and poverty counts skyrocket—and stay sky-high for years. The technology to protect the middle class from slipping into poverty, and the poor from sinking even deeper, is still rudimentary in the developing world. Just think of the scant coverage of unemployment insurance.

But the real breakthrough is that, to raise productivity, expand opportunity, or reduce risk, you now have a power tool: direct cash transfers. Most developing countries (thirty-five of them in Africa) have, over the last ten years, set up logistical mechanisms to send money directly to the poor—mainly through debit cards and cell phones. Initially, the emphasis was on the conditions attached to the transfer, such as keeping your child in school or visiting a clinic if you were pregnant. It soon became clear that the value of these programs was to be found less in their conditions than in the fact that they forced government agencies to know the poor by name. Now we know where they live, how much they earn, and how many kids they have.

That kind of state–citizen relationship is transforming social policy. Think of the massive amount of information it is generating in real time—how much things actually cost, what people really prefer, what impact government is having, what remains to be done. This is helping improve the quality of expenditures, that is, better targeting, design, efficiency, fairness, and, ultimately, results. It also helps deal with shocks like the global crisis (have you ever wondered why there was no social explosion in Mexico when the US economy nose-dived in early 2009?). Sure, giving away taxpayers’ money was bound to cause debate (how do you know you are not financing bums?). But so far, direct transfers have survived political transitions, from left to right (Chile) and from right to left (El Salvador). The debate has been about doing transfers well, not about abandoning them.

A final point. For all the promise of new poverty-reduction techniques, just getting everybody in the developing world over the two-dollar-a-day threshold would be no moral success. To understand why, try to picture your own life on a two-dollar-a-day budget (really, do it). But it would be a very good beginning.

Marcelo M. Giugale is the Director of Economic Policy and Poverty Reduction Programs for Africa at the World Bank and the author of Economic Development: What Everyone Needs to Know. A development expert and writer, his twenty-five years of experience span Africa, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin-America and the Middle-East. He received decorations from the governments of Bolivia and Peru, and taught at American University in Cairo, the London School of Economics, and Universidad Católica Argentina.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Can we end poverty? appeared first on OUPblog.

Four years ago this week, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Caribbean nation of Haiti. The tragedy left 1.5 million citizens displaced from their homes, hundreds of thousands dead and devastated an already depressed economy.

Four years ago this week, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Caribbean nation of Haiti. The tragedy left 1.5 million citizens displaced from their homes, hundreds of thousands dead and devastated an already depressed economy.

Today, Haiti remains the poorest country in the Americas. And while much has been done to aid Haiti’s recovery, a staggering eighty percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

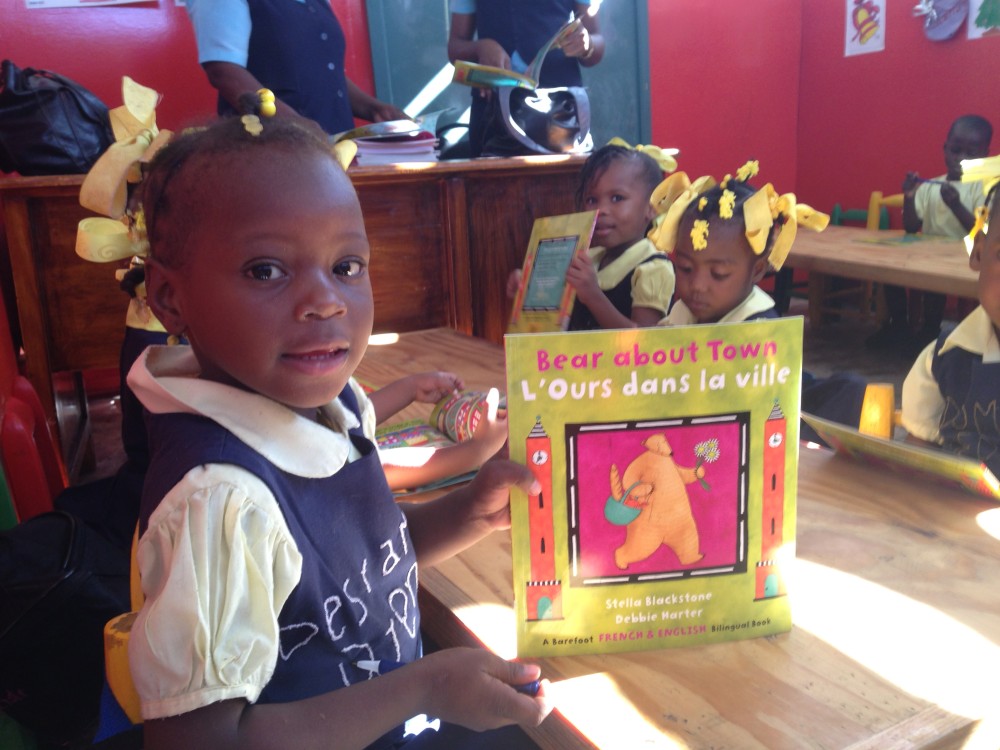

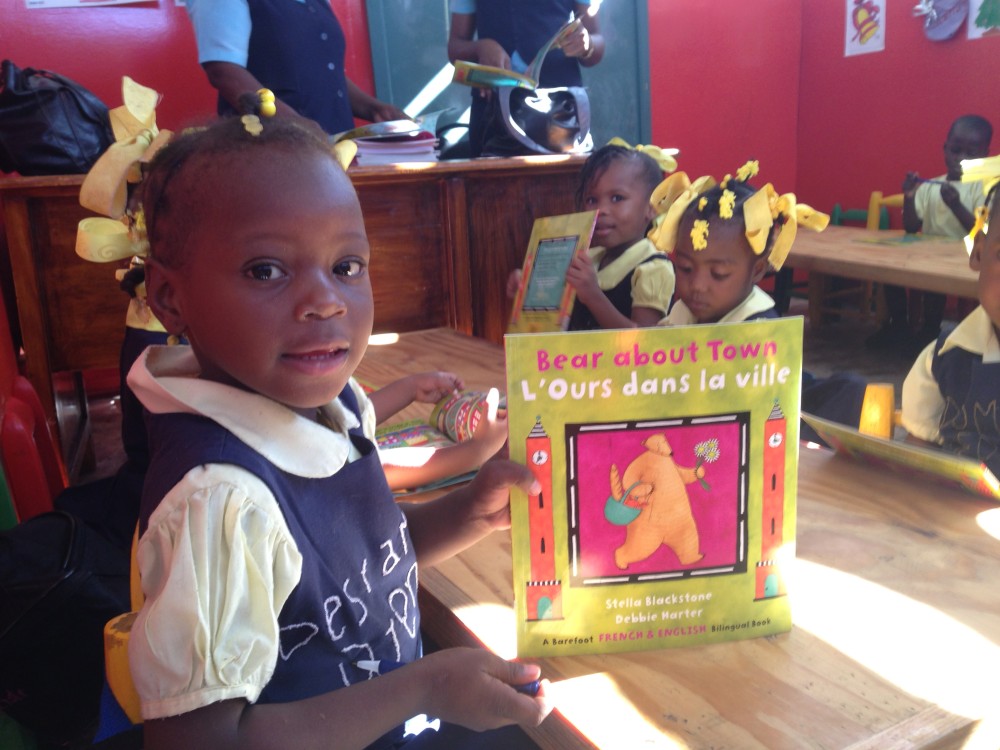

Poverty keeps millions of children from accessing the world of knowledge that books provide. First Book is committed to changing that, by bringing badly-needed books and educational materials to children in countries like Haiti. Last month we had the opportunity to deliver books to kids in Haiti’s capital city of Port au Prince, a donation made possible through First Book’s longstanding partnership with Jet Blue.

At Ecole Herve Romain, a local school in the Port au Prince “red-zone” of Bel-Air known for high crime and extreme poverty, 250 students previously had to share 50 books between them. Now they have a library of 500 new titles to read and explore.

In addition to providing books, First Book staff met with representatives from USAID and other global and national NGOs in hopes of creating partnerships that lead to more educational resources for Haiti’s kids in need.

“We believe that one book can change the world,” said Kyle Zimmer, president and CEO of First Book. “But we also know that building relationships with partners in Haiti and around the globe will be critical in to achieving our goal of providing books and educational resources to 10 million children in need worldwide by 2016. We want to understand local needs and connect the dots so that kids in need all over the world can read, learn and rise out of poverty.”

The post In a Haitian School, 50 Books for 250 Students appeared first on First Book Blog.

By Peter Gill

International responsiveness to the food crisis in the Horn of Africa has relied again on the art of managing the headlines. Sophisticated early warning systems that foresee the onset of famine have been in place for years, but still the world waits until it is very nearly too late before taking real action – and then paying for it.

The big aid organisations, official and non-government, are right to say they have been underlining the gravity of the present emergency for months, at least from the beginning of the year. On June 7 FEWS NET (the Famine Early Warning Systems Network funded by USAID) declared that more than seven million in the Horn needed help and the ‘current humanitarian response is inadequate to prevent further deterioration.’ Two seasons of very poor rainfall had resulted ‘in one of the driest years since 1995.’ Still the world did not judge this to be the clarion call for decisive intervention.

Three weeks later, on June 28, OCHA (the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) said that more than nine million needed help and that the pastoral border zones of Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya were facing ‘one of the driest years since 1950/51.’ Six decades! Two generations! A story at last! The media mountain moved, and the NGO fund-raisers marched on behind.

I have The Times of July 5 in front of me. ‘Spectre of famine returns to Africa after the worst drought for decades,’ says the main headline in World news. On page 11 there is a half-page appeal from Save the Children illustrated with a picture of a six-week old Kenyan called Ibrahim ‘facing starvation.’ On page 17 Oxfam has its own half page saying that ‘more than 12 million people have been hit by the worst drought in 60 years.’ The Times that day also carried a Peter Brookes cartoon of a hollow-faced African framed in the map of Africa, with his mouth opened wide for food.

So, for 2011, an image of Africa has again been fixed in the western consciousness. It is an image of suffering – worse, of an impotent dependence on outsiders – that most certainly exists, but is only part of the story, even in the Horn.

The western world may understand something of the four-way colonial carve-up and the post-colonial disaster that overtook the Somali homeland, but it certainly has no proper answers to the conflicts and dislocation that lead to starvation and death. In northern Kenya, to which so many thousands of Somali pastoralists have fled in recent months, the West does have an answer of sorts – it can feed people in the world’s largest refugee camp, in the thin expectation of better times back across the border. Then there is Ethiopia, with several million of its own people needing help, its own Somali population swollen by refugees, and the country for ever associated with the terrible famine of 25 years ago which launched the modern era of aid.

Here it is possible to make some predictions. There will be no widespread death from starvation in Ethiopia, not even in its own drought-affected Somali region where an insurgency promotes insecurity and displacement. New arrangements between the Ethiopian government and the UN’s World Food Programme have insured more reliable and equitable food distribution, and the Government presses on with schemes to settle pastoralists driven by persistently poor rains from their semi-nomadic lifestyles.

The government of Meles Zenawi, which has just marked 20 years in power, has on the whole a creditable record in response to the prospect of famine.In 2003/4 the country faced a far larger food crisis than it did it in 1984, but emerged from it with very few extra deaths. In the former famine lands of the North where there is an impressive commitment to grass-roots development there is almost no chance of a retu

Yesterday was Peace Day – thousands of people around the world stopped to stand together for a world without conflict, for a world united:

PEACE is more than the absence of war.

It is about transforming our societies and

uniting our global community

to work together for a more peaceful, just

and sustainable world for ALL. (Peace Day)

There is an ever-increasing number of children’s books being written by people who have experienced conflict first hand and whose stories give rise to discussion that may not be able to answer the question, “Why?” but at least allows history to become known and hopefully learnt from.

For younger children, such books as A Place Where Sunflowers Grow by Amy Lee-Tai and illustrated by Felicia Hoshino; Peacebound Trains by Haemi Balgassi; and The Orphans of Normandy by Nancy Amis all  focus on children who are the innocent victims of conflict. We came across The Orphans of Normandy last summer. I was looking for something to read with my boys on holiday, when we were visiting some of the Normandy World War II sites. It is an extraordinary book: a diary written by the head of an orphanage in Caen and illustrated by the girls themselves as they made a journey of 150 miles to flee the coast. Some of the images are very sobering, being an accurate depiction of war by such young witnesses. It worked well as an introduction to the effects of conflict, without being unnecessarily traumatic.

focus on children who are the innocent victims of conflict. We came across The Orphans of Normandy last summer. I was looking for something to read with my boys on holiday, when we were visiting some of the Normandy World War II sites. It is an extraordinary book: a diary written by the head of an orphanage in Caen and illustrated by the girls themselves as they made a journey of 150 miles to flee the coast. Some of the images are very sobering, being an accurate depiction of war by such young witnesses. It worked well as an introduction to the effects of conflict, without being unnecessarily traumatic.

The story of Sadako Sasaki, (more…)

Four years ago this week, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Caribbean nation of Haiti. The tragedy left 1.5 million citizens displaced from their homes, hundreds of thousands dead and devastated an already depressed economy.

Four years ago this week, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Caribbean nation of Haiti. The tragedy left 1.5 million citizens displaced from their homes, hundreds of thousands dead and devastated an already depressed economy.

The 2007 Jane Addams Children’s Book Awards will be presented Oct. 19/07 in New York City. A Place Where Sunflowers Grow is one of this year’s winners! www.janeaddamspeace.org has more information on the 6 award winners this year as well as the previous winners.

Thanks for pointing that out, Corinne. Also, Weedflower by Cynthia Kadohata is one of the other 2007 award winners.

What a great topic to highlight. It would be interesting to see how many non WWII books there are out there on the topic of peace. I should do some scrounging around. Here in Canada, Deborah Ellis has published a number of books about middle east. The Breadwinner and Parvana’s Journey deal with a young girl growing up in Afghanistan. Mmmm. I’ll have to keep thinking about all this.

You raise an interesting point and if you do find anything interesting, do let us know. Thank you for pointing out Deborah Ellis’ books. She is a very powerful writer and you can read a bit of background to her Breadwinner Trilogy in an interview with her on PaperTigers. We will also be reviewing her most recent book, Sacred Leaf, in our next issue. The sequel to I Am a Taxi, it is all about conflict too, focussing on issues within Bolivia about the coca plant, and indirectly on the influence of the US on government policy…