new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Coetzee, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 13 of 13

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Coetzee in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Celine Aenlle-Rocha,

on 9/15/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

literary criticism,

Philosophy,

Coetzee,

fiction writers,

Irish Literature,

Alice Munro,

Brian Moore,

*Featured,

denis sampson,

john mcgahern,

Arabella Kurtz,

David Attwell,

modern literature,

Outstaring Nature's Eye,

The Found Voice,

The Good Story,

Writers' Beginnings,

Add a tag

Throughout his career, J. M Coetzee has been centrally preoccupied with how to tell the truth of an individual life, most of all, how to find the appropriate narrator and fictional genre. Many of his fifteen novels disclose first person narrators in a confessional mode, and so it is not altogether surprising that his latest book is a dialogue with a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, in which they explore together notions of selfhood, repression, disclosure and the nature of communication.

The post Coetzee’s Dialogues: Who says who we are? appeared first on OUPblog.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 9/11/2016

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novels,

Coetzee,

Add a tag

Whenever I write about a new Coetzee book, I am wary. I think back to

what I wrote in 2005 about

Slow Man when it was new, and I cringe. On the one hand, I'm glad to have this record of a first encounter; on the other, the inadequacies of a first encounter with a new Coetzee novel are immense. (With

Slow Man, I learned this vividly a few months later after the book wouldn't stop haunting me, and I reread it, and it was a different book, one I had learned to read only after reading it.) The first sentence of

my 2008 Diary of a Bad Year post is: "This is a book that will need to be reread. Until then, some notes." For the next book,

Summertime (2009), I didn't write anything until I could spend time thinking and re-thinking it, particularly as it was the final part of a trilogy of fictionalish autobiographies; I first wrote about it in

my Conversational Reading essay on Coetzee and autobiography. For

The Childhood of Jesus (2013), I returned to recording my initial impressions, but clearly labeled them as such. I will do the same here, with

Childhood's sequel, recently released in the UK and Australia (it's scheduled for release early next year in the US).

Some preliminary, inadequate notes on

The Schooldays of Jesus after a first reading:

There will be debate about whether it's possible to read

The Schooldays of Jesus without having read

The Childhood of Jesus. I think you could have a good, or at least adequate, experience of

Schooldays without

Childhood. They don't rely on each other for plot. What the novels together gain is resonance.

Reading

The Childhood of Jesus the first time through was for me a profoundly disorienting experience, because right through the last page I just didn't know what Coetzee was up to. (It was much like the experience of first reading

Elizabeth Costello.) Reading

Schooldays was far less disorienting because the territory felt at least a little bit familiar. I was ready for the enigmas. I had learned how to read.

There is no dedication.

Childhood was dedicated "For D.K.C." —

David Coetzee. In place of the dedication there is an epigraph from

Don Quixote, a book highly important to

Childhood but much less present in

Schooldays: "Algunos dicen: Nunca segundas partes fueron buenas." Here's the context of that sentence in Edith Grossman's

translation:

“And by any chance,” said Don Quixote, “does the author promise a second part?”

“Yes, he does,” responded Sansón, “but he says he hasn’t found it and doesn’t know who has it, and so we don’t know if it will be published or not; for this reason, and because some people say: ‘Second parts were never very good,’ and others say: ‘What’s been written about Don Quixote is enough,’ there is some doubt there will be a second part; but certain people who are more jovial than saturnine say: ‘Let’s have more quixoticies: let Don Quixote go charging and Sancho Panza keep talking, and whatever else happens, that will make us happy.’”

The first chapter of

Schooldays is a perfect short story. Coetzee almost never writes short stories, and the various segments of his novels typically rely on each other, but I had the feeling after reading this first chapter that even if the rest of the book were a dud, these twelve pages were rich enough to satisfy me.

Dogs are, once again, everywhere. Dogs as creatures wandering through the book, yes, but also dogs as metaphors and figures of speech. There will one day be entire Ph.D. dissertations devoted to Coetzee's dogs.

I will be curious to see if the US edition calls the child David or Davíd. He is the latter in the UK edition. I don't have the UK edition of

Childhood, but some of the UK reviews put the accent on the i, so I assume his name is spelled that way in it, unlike the US edition, where he is simply David. Both novels concern themselves with names and naming, and names are significant to most of Coetzee's work (in one of the best studies of that work,

J.M. Coetzee: Countervoices, Carrol Clarkson devotes

an entire chapter to names). Yet there is a sense through both books that names are not all

that important, that they are temporary, that there are "real names" beyond the everyday ones, and those ones matter, but the everyday names could be anything. Even Coetzee pronounces them differently: in December 2012, just before

Childhood was published,

he pronounced them in the Anglicized way:

Seye-mon and

Day-vid. By early 2013,

he was pronouncing David as Dah-

veed (one contextual difference: in the first, Coetzee is introducing the characters himself, and they aren't named in the passage he reads [most of the time in the book, David is "the boy" and Simon is "he"]. In the second, Simón is pronouncing Davíd's name. This might not matter except that the complexity of the linguistic situation in the book might make it that Simón is trying to speak Spanish, the dominant language in Novilla but not his native language. However, though I usually think Coetzee is going for the most subtle, complex, and multivalent possibilities, in this case I really do expect he just changed his mind.)

Simón's name is used much more in

Schooldays than it was in

Childhood. It's as if he's growing into it. Coetzee loves playing with pronouns and antecedents, and in

Schooldays, Simón's name is usually used in the narration via the construction "he, Simón". He's being named, pointed to,

hailed into identity (and ideology?). Perhaps one of the reasons for his constant tension with Davíd is the boy's resistence to such identity. (It's not that Davíd is without identity, but that he is more mysterious in his identity than Simón. Simón is simply unable to comprehend Davíd's identity, it seems. Certainly, Davíd believes that to be true.)

Though their titles lead us to think these novels are about the child, the main character is Simón. It's his consciousness that we have access to, his experiences that we see. One of the questions these books dramatize is: What is it to be responsible for the life and welfare of a child whom you can't understand, a child whose own view of the world is so clearly different from your own, a child who is alien to you. (A fascinating comparison: Doris Lessing's

The Fifth Child and

Ben, in the World.) Do we want Simón to give up on Davíd, to let him go? After all, Simón is, as Davíd repeatedly points out, not his "real father", just a caretaker, and he has fulfilled his duty as he originally perceived it. And yet there is responsibility for this young life, as difficult and confounding as that responsibility may be. Inés may have accepted the label of "Davíd's mother", but she doesn't seem much interested in the actual role. Simón is far more conscientious, recognizing that there is something beyond and outside of Davíd's behavior/personality/self/whatever that he must try to take care of.

One of the new characters in

Schooldays is Dmitri, a man who tends the local art museum, hangs around the dance academy that Davíd enrolls in, and more or less befriends Simón for a while. He's one of those familiar Coetzee characters who shows up, makes a mess of things, and refuses to go away. He returns us to names — it is no coincidence that there are two Russian names in the book: Dmitri and Alyosha. We can't help but think of

The Brothers Karamazov, and the personalities of Coetzee's Dmitri and Alyosha fit generally (or allegorically or stereotypically) with the personalities of Dostoevsky's. This makes me think of the end of

Coetzee's first correspondence with Arabella Kurtz (which would eventually lead to

The Good Story):

I think back to The Brothers Karamazov, where the storyteller distinguishes between those of us whose thinking is disordered and those whose minds work tidily and efficiently. He belongs (more or less) among the latter: he sees the Karamazovs as cautionary examples of where disordered thinking can land one. I hear what he says. Nevertheless, my sympathies are with the Karamazovs.

Order and disorder are ideas that run all through both books, and

Schooldays enriches some of the discussions of rationalism and mysticism in

Childhood via the academy of dance that Davíd enrolls in. The school's philosophy is utterly mystical. It carries forward some of the discussion of numbers and pedagogy from

Childhood, where, for instance, Simón says of David, "Most of the time ... I think the child simply doesn't understand numbers, the way a cat or a dog doesn't understand them. But now and then I have to ask myself: Is there anyone on earth to whom numbers are more real?" At the academy, the teacher says:

Uno-dos-tres: this this just a chant we learn at school, the mindless chant we call counting; or is there a way of seeing through the chant to what lies behind and beyond it, namely the realm of the numbers themselves — the noble numbers and their auxiliaries, too many to count, as many as the stars, numbers born out of the unions of noble numbers?...

To bring the numbers down from where they reside, to allow them to manifest themselves in our midst, to give them body, we rely on the dance. Yes, here in the Academy we dance, not in a graceless, carnal, or disorderly way, but body and soul together, so as to bring the numbers to life. As music enters us and move us in dance, so the numbers cease to be mere ideas, mere phantoms, and become real.

Davíd loves dancing the numbers, and has a particular talent for it. This is not, though, an uplifting movie-of-the-week in which a difficult/troubled child discovers a talent and becomes a great person and everyone lives happily ever after. Davíd's talent gives him some pleasure and sense of accomplishment, and it pleases some audiences, but that's about it. Other circumstances intervene, and Davíd ends the book more or less as he began. Simón, though, does not. The final pages are evocative and enigmatic, but within the enigma one thing becomes clear, and I found it remarkably moving: Simón has changed, his senses and perceptions are widening. For all the mysteries and frustrations he has endured throughout the two books, Simón has now, by the end of

Schooldays, found a moment of new possibility not for anyone else, but for, finally, himself.

There is much more to say and explore through this novel. (We still don't have any good answer to why these books are titled as they are. Is "Jesus" Davíd's "real name"? Does the biblical allusion allow Coetzee a comfort with allegory that he has never had access to before?) However, I have only read it once, and I know better than to trust any of my conclusions about Coetzee's writing after only one read. I will simply say: This second part is very, very good. Let’s have more quixoticies.

In

my review of John Clute's collection Stay, I had some fun at Clute's expense with his passionate hatred of certain types of academic citation, and I pointed out that often the problem is not with the official citation format, which usually has some sort of logic (one specific, perhaps, to its discipline), but rather that the problem is in the failure to follow the guidelines and/or to adjust for clarity — I agreed that some of the citations used in Andrew Milner’s

Locating Science Fiction are less than helpful or elegant, but the fault seemed to me to lie at least as much with Milner and Liverpool University Press as with the

MLA or

APA or

University of Chicago Press or anybody else. Just because there are guidelines does not mean that people follow them.

I now have an example from an MLA publication itself, and it's pretty egregious, though I may only feel that way because it involves me.

The citation is in the book

Approaches to Teaching Coetzee's Disgrace and Other Works edited by Laura Wright, Jane Poyner, and Elleke Boehmer, published by the MLA as part of their

Approaches to Teaching World Literature series. It's a good series generally and it's a good book overall.

But in Patricia Merivale's essay "Who's Appropriating Whose Voice in Coetzee's

Life & Times of Michael K", we see this passage on page 153:

Most Coetzee critics seem more committed to the "movements" [of the mind] than to the "form." Teachers of Coetzee should attempt to redress the balance, perhaps by following Michael Cheney's blogged example: "I realized that I was marking up my teaching copy of Michael K, as if I were marking up a poem ... lots of circled words, [and] 'cf.'s referring me to words and phrases in other parts of the book ... an overall tone-structure, a scaffold of utterance" (my emphasis).

The sentiment and some of the phrasing in that quotation seemed familiar to me, as did the writer's last name. Could there be a Michael Cheney out there writing about Coetzee? Sure. (I recently met

Michael Chaney, a wonderful scholar at Dartmouth. We had fun trying to decide who's a doppelgänger of whom...) But I was suspicious. I looked at the Works Cited section of the book and found this:

Cheney, Michael. "Review of Life & Times of Michael K." J.M. Coetzee Watch #12. Matilda. Perry Middlemiss, 22 Oct 2008. Web. 21 Aug. 2009.

Apparently, there actually is a Michael Cheney out there writing about Coetzee. Good for him! But what is this

J.M. Coetzee Watch? Sounds like something I'd be interested in. And

Matilda? And Perry Middlemiss? Huh?

After a few Google searches, I found the source. It is this: A blog called

Matilda run by Perry Middlemiss, with a series of linkdump posts titled "J.M. Coetzee Watch". In

"J.M. Coetzee Watch #12", we find this paragraph:

Review of Life and Times of Michael K.

Michael Cheney, whose "The Mumpsimus" weblog is one of the best litblogs around, has been teaching Life and Times of Michael K. for his course on Outsiders, considers what appeals to him about Coetzee: "As I read Michael K. this time, I tried to think about what it is in Coetzee's work that so appeals to me. It's no individual quality, really, because there are people who have particular skills that exceed Coetzee's. There are many writers who are more eloquent, writers with more complex and evocative structures, writers of greater imagination...And then I realized that I was marking up my teaching copy of Michael K. as if I were marking up a poem. I looked, then, at my teaching copy of Disgrace, from when I used it in a class a few years ago. The same thing. Lots of circled words, lots of 'cf.'s referring me to words and phrases in other parts of the book. Lots of sounds building on sounds, rhythms on rhythms in a way that isn't particularly meaningful in itself, but that contributes to an overall tone-structure, a scaffold of utterance to hold up the shifting meanings of the story and characters."

Well, golly. Michael Cheney is me! Thank you, Perry Middlemiss, for the kind words. I don't even especially care that my name is wrong there, because at least the post includes a link so that readers can follow it back to my own post

"Scattered Thoughts on Michael K. [sic] and Others". (I've added that

[sic] there to point out my own mistake of adding a period to the title of

Life and Times of Michael K, which I unthinkingly did back then. Merivale changed at least one of those periods to a comma when [mis]quoting me. Mistakes upon mistakes upon mistakes...) Michael K, Michael Cheney — easy to see how such a mistake could be made. People make mistakes in blog posts; it goes with the territory of writing quickly, sometimes haphazardly, without an editor.

But I'm less forgiving of Patricia Merivale's mistake, because hers is not in a blog post but rather a book — a book published by

the major professional organization for our discipline — and it's a mistake that would have been at least ameliorated if she had taken the minor effort of actually following the link back to its source. Which is what you are supposed to do, especially if you are a scholar. ("Whenever you can, take material from the original source, not a secondhand one." MLA Guideline 6.4.7, both 6th and 7th editions of the

MLA Handbook.) I make first-year undergraduates do this, and they whine and complain, but the value is clear. Trace the source back to its origin if at all possible, because if you don't, the chance of replicating somebody else's mistakes, or at least their assumptions, is much greater.

If Patricia Merivale had made the tiny effort of clicking on that link and tracing the source back to its origin, she would have discovered that 1.) my name is Matthew Cheney, not Michael Cheney; and 2.) it's not a book review, it's an informal, scattered blog post that I happened to write on my birthday in 2008.

Even though the MLA guidelines for citation of electronic sources changed a bit just as Merivale was writing her essay (the 7th edition of the

MLA Handbook came out in 2009), Merivale's citation is wrong in multiple ways under any version of the MLA guidelines — she didn't go back to the original source, she mistakes a subheading for a title in Middlemiss's post, she italicizes the name of the post (should be in quotes, with the title of the site italicized), she throws in Middlemiss's name without indicating why (at the least it should be "

Matilda. Ed. Perry Middlemiss." — though that would be nonstandard, it at least would be clearer). And though the current guidelines for MLA do not require that a URL be included, it's allowed (see 5.6.1 or the

Purdue OWL), and in this case it would have been helpful — I tell students that if they're struggling to figure out what to do with a web citation, to include the URL just for good measure, since it may save a reader time in tracking down the source, even if the URL changes (because maybe

the Wayback Machine got it).

Anyway, the point is: Merivale's citation is unambiguously, absolutely wrong.

And it got into an MLA publication. Mistakes happen, and in a book like this one with 20 pages of Works Cited, mistakes are almost inevitable. Merivale's original citation is a disaster, and more careful editors would have caught it because it is nonstandard and can't be parsed according to any MLA guidelines I know.

Does it matter? Not much. Sure, I'd like my name to be known correctly. I'd also like as many citations as I can get, since in academia, highly-cited writers have far more success than less-cited writers. But there's no way that one blog post being cited in one article in one book in a large series of books is going to have a big effect on my life or career.

But it's annoying. And it's disappointing. Scholars should be better than this. We should be especially careful with our citations, because we all know that we live and die by citation. Merivale's and the editors' failures here were easily preventable. That citation is flat-out wrong because nobody took the time to do it right, and doing it right would not have required a lot of effort or even special knowledge.

Trace your sources back to their origin if at all possible, double-check people's names, follow the basic guidelines in the

MLA Handbook.

Here, for the record, is a better version of that citation:

Cheney, Matthew. “Scattered Thoughts on Michael K. and Others.” The Mumpsimus. 17 Oct. 2008. Web. 2 June 2015.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 10/17/2014

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

novels,

Coetzee,

Add a tag

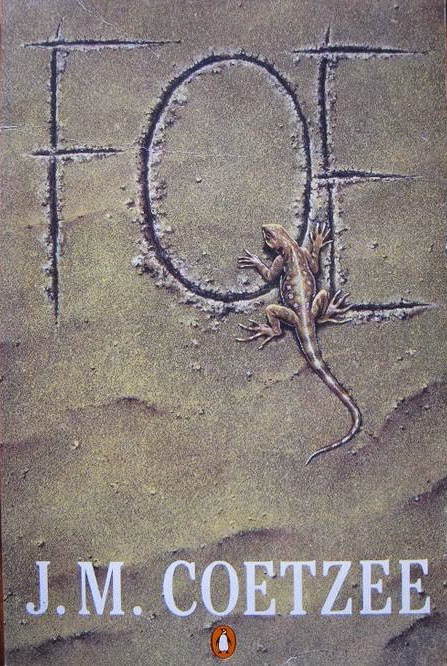

Though J.M. Coetzee's work has long

fascinated me, I've avoided writing anything on

Foe, because every time I tried to write anything, it felt obvious and stupid. It's the same feeling I've gotten whenever I've tried to write about Samuel Beckett or Franz Kafka, two other favorites of mine. Perhaps what has defeated me with writing about

Foe is something similar to what defeats me whenever I've tried to write about Beckett and Kafka, who were, in fact, considerable influences on Coetzee — their work is so

what it is that to add words around it feels inevitably reductive, a violence against the art.

I recently tried again with

Foe, and while it didn't feel quite as stupid and reductive as previous attempts — indeed, the writing helped me clarify some of my ideas about what the novel is up to — I don't think I'm going to go on. I started with a couple of passages toward the end of the book, and thought that might bring me back toward earlier parts, but as I started toward the earlier material, the feeling began again, the feeling of it being pointless — worse,

harmful — to keep emitting utterances around that which defies language.

Here, then, are two basically first-draft almost-essays about the end of

Foe, in case they are of any interest...

1. pp. 123-126 [US Penguin edition]

At the end of the first paragraph of this passage, Susan claims herself as “father to my story”. Foe then tells the first of his parables (anecdotes? tales?), one that centers on confession and the idea of “true” confession.[1]

A woman who was convicted as a thief confessed that her first confession was false: she unleashes a torrent of confession on a minister, who becomes skeptical.

The woman says, “And if my repentance is not truly felt (and is it truly felt? — I look into my heart and cannot say, so dark is it there), then is my confession not false, and is that not sin redoubled?” (124). Confession here moves from being a true account to a true feeling, and the link with repentance elides any difference between the two: unfelt repentance = false confession. (Echoes of Disgrace here.)

Foe seems to believe that the woman’s confession in his story is a tactic, for he says, “And the woman would have gone on confessing and throwing her confession in doubt all day long…”, which suggests she is not so much telling a true story as behaving like Scheherazade, trying to forever defer her death through storytelling. Foe’s expression of what he thinks the moral of the story is boils down to: at some point, you’ve got to stop telling stories and accept the effects of the stories that have been told, particularly with regard to the story of our self. (I think of Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Nighthere, where in an introduction Vonnegut says it is the only one of his novels that he knows the moral, and the moral is: “Be careful what you pretend to be, for you are what you pretend to be.”)

Susan disagrees with that interpretation. “To me,” she says, “the moral is that he has the last word who disposes over the greatest force” (124). Susan knows that the storyteller only has power so long as the auditor is willing to keep listening. The real power is with the king or executioner: whoever can, at any moment, say, “Stop. Now I will kill you.” Here, I think, we see the difference in Foe and Susan’s experiences of power. Susan’s experience is that of a woman in patriarchy — no matter what she does, no matter who she is, it is always he who has the last word.

Foe tells a second story: a condemned woman seeks someone to take care of her child; one of the jailers agrees to, and the woman goes to her death content. This is a parable of procreation and progeny: instead of sending stories off into the world, this woman sends a child, and the child is a continuation of the self, providing a different sort of posterity. Foe interprets it as a way “of living eternally” (125).

Susan seems to misinterpret this parable — she’s good at understanding storytelling, but not so good at understanding parenting, it seems. She immediately interprets Foe’s “living eternally” as “fame”, which is not at all what he said. Foe’s was a more biological idea: the passage of a self encoded in genes from one generation to the next. Susan wants Foe to give her new clothes and a letter of recommendation so that she can get a job in domestic service: “I could return,” she says, “in every respect to the life of a substantial body” — but that’s exactly what Foe was talking about in the previous parable: the substantial body of the child outlives the body of the mother and thus carries on heredity. Susan’s silence about her daughter here is notable, because that would seem to be the logical subject to bring up: “At least the woman in your parable knew where her daughter was,” Susan could say. But she doesn’t. She brings it all back to herself. “I remain as ignorant as a newborn babe,” she says (126). She here is in the child position … but who was her mother? Mothers don’t make stories, for stories are, she says, fathered. It seems to me that the novel is somehow getting at ideas of failed or deferred or broken motherhood. (And I haven’t said anything about these interesting sentences from before: “But such a life is abject. It is the life of a thing. A whore used by men is used as a substantial body” [126]. This is Susan rejecting bodily life, striving, as always, for the life of storytelling. But stories are breaths and bits of ink, not life.)

2. Chapter IV

Chapt. III begins: “The staircase was dark and mean.” Chapt. IV: “The staircase is dark and mean.”

(Darkness again. One could easily write a 30-page paper on the words “dark” and “darkness” in Foe.)

IV continues differently, though: where III continues with “My”, IV gives us a body: something substantial, “a woman or a girl” (153). She can be picked up, she has substance, but she “weighs no more than a sack of straw”.

The bodies in the bed, with skin “dry as paper”, are introduced first as a pronoun: “They lie side by side in bed, not touching.” The pronoun has no antecedent for the reader. We can fill it in ourselves with suspicions. If we were reading grammatically (Coetzee knows this, tempts us toward this), the antecedent is “a mouse or a rat”. But rather than living (substantial) animals (rodents, vermin), what we have are dessicated bodies, bodies similed into paper.

“I draw the covers back.” As if pulling a book open.

In an alcove: Friday, in “pitch darkness” (154). Matches “will not strike”. “I find the man Friday stretched at full length on his back. I touch his feet…” Once again, the fetish of Friday’s feet. Susan always wants shoes; Friday always wants bare (life?) feet. (Susan always desires stories, always flees bare life through the distance of tales. Friday desires — if the figure of Friday can be said to “desire” anything — flesh against soil, cobblestone, floor.)

Friday has a pulse. In his throat. “From his mouth, without a breath, issue the sounds of the island.” It is as if the pulse produces the sounds. But the sounds of the “faraway roar” are ones the narrator expects, ones previously reported, for that faraway roar, perceived as “the roar of waves in a seashell” is “as she said”.

A break in the text.

A plaque, a sign: Daniel Defoe, Author. We know Foe, not Defoe. The sign is a mark, the author an authority, and the sign enacts his authority. The authority of a byline. It is not free-floating, it is nailed to a wall. Did Daniel Defoe author(ize) this room?

A few paragraphs later, we get the first sentence of the book we’ve been reading, but now with a salutation: “Dear Mr. Foe, At last I could row no further” (155). Taken on its own, it sounds like a suicide note. The salutation directs it. We have repeatedly had clues suggesting that Chapter I (numeral and singular personal pronoun) is not the spoken text we probably first took it to be: the ship’s name rendered typographically was the first clue, and here we are encouraged to see Chapter I as similar to, if not exactly the same as, the epistolary Chapter II.

At any rate, here the narrative splits without a textual break: the narrator now appropriates some of the words of the first pages, here without quotation marks and here in the present tense.

With a sigh, with barely a splash — a sigh, a breath. (Stories require breath. Friday has a pulse.)

The dark mass of the wreck is flecked here and there with white. … It is like the mud of Flanders, in which generations of grenadiers now lie dead, trampled in the postures of sleep. … In the black space of this cabin the water is still and dead, the same water as yesterday, as last year, as three hundred years ago. Susan Barton and her dead captain…. I crawl beneath them. … But this is not a play of words. … This is a place where bodies are their own signs. It is the home of Friday. (156-157)

And now, again, at the end, a beginning: Friday’s mouth opens. “From inside him comes a slow stream, without breath, without interruption.” He speaks without breath. This is not a story or confession, but something else. Something uninterrupted. It is bodily, and conveyed bodily. What it is, we do not know: it is it, pronoun, no antecedent. Soft, cold, dark, “unending”.

it beats against my eyelids

The eye/I. Friday’s eyes on feet (147), “dark to my English eye” (146), Foe says Friday rowed across a “dark pupil” or “dead socket” an “eye staring up at him from the floor of the sea” — “but I should have said the eye, the eye of the story” (141).

it beats against my eyelids

against the skin of my face.

We end, then, with Friday’s unbreathed story beating against closed eyes and (white?) skin.

In fact, in the spiritual world, we change sexes every moment.

--Ralph Waldo Emerson, Representative Men

I object to anything that divides the two sexes ... human development has now reached a point at which sexual difference has become a thing of altogether minor importance. We make too much of it; we are men and women in the second place, human beings in the first.

--Olive Schreiner to Havelock Ellis, 19 Dec 1884 [quoted in Monsman]

I first tried to read

The Story of an African Farm some years ago when I went on a

Doris Lessing binge; I hadn't heard of the novel before reading Lessing's praise of it, and what she said intrigued me. But I went into

The Story of an African Farm expecting it to be, well,

a story, and it was soon apparent that, for all the book is, it is only "a story" in the loosest sense -- indeed, it's more accurate to say it is a book containing a lot of stories, but even that misses much of what is wonderful and unique in Olive Schreiner's creation.

The next time I thought about reading

African Farm was when I first encountered J.M. Coetzee's

White Writing, wherein Coetzee seems somewhat dismissive of the book, noting that it is a kind of fantasy because the reader gains almost no sense of how the farm in the novel is able to be sustained. I then assumed

African Farm to be just another Africa-as-exotic-setting novel, something of historical interest perhaps, but not much more than that.

As I was first thinking about putting together a new version of my

Outsider course, though, I came upon some references to Schreiner and this novel that piqued my interest and brought me back to it. I wanted some context to consider the book in, so I grabbed library copies of

Olive Schreiner's Fiction: Landscape & Power by Gerald Monsman and

Olive Schreiner

by

Ruth First and Ann Scott. These were extremely helpful, especially the Monsman, because he provides a valuable analysis of the book's structure, defending it from the many critics who have said that

African Farm, whatever its virtues, is a failure as a novel. Monsman places the book within a tradition of philosophical novels such as those by

Walter Pater and

Thomas Carlyle, although Schreiner's book is, to my mind at least, more accessible and emotionally affecting than those. Nonetheless, they are important to mention in any defense of Schreiner, because it's too easy to assume a narrow definition of "the novel" and judge Schreiner a failure against it. She clearly wasn't tr

Rain Taxi Review of Books is a marvelous magazine, and they've just begun their annual auction, which is an event I always look forward to because of the wide variety of items they have to offer, including dozens of signed books.

The new print issue of RT includes an essay I wrote about the work of Wallace Shawn, a playwright and essayist whose face and voice many people know from some of his iconic roles in movies and TV shows, but whose writing is vastly less known -- he's one of those writers who is more popular outside of his native country than in it.

Aside from a couple short stories that are currently wending their way through the submission process, my major writings since this summer have been the Shawn essay for RT and the essay on Coetzee for The Quarterly Conversation. The effect of spending so much time reading and re-reading the writings of both men is obvious in my latest Strange Horizons column, "On the Eating of Corpses".

I had promised myself I would not blog again until I had finished x, y, and z, and while x and y are finished, z (an essay about J.M. Coetzee's memoir-novels) is beating me up and winning.

But I'm going to pause in the fight for a moment and break my self-promise because today I discovered Aaron Bady's astoundingly excellent blog Zunguzungu via a marvelous post Bady wrote at The Valve about Chinua Achebe and the African Writers Series (a post that previously appeared on Zunguzungu).

It's been a long time since I last encountered a blog where the excitement of discovery came from finding someone giving expression to inchoate thoughts I'd never quite found words for, but that happened again and again as I read through Bady's blog, especially the post "When Good People Write Bad Books" and this earlier Achebe post, referencing Norman Rush (whose Mating I adore, or, at least, I adored when I read it about ten years ago) to explore the idea of "great writers" and who has the authority to write about/represent particular cultures in writing -- the discussion in the comments section is as wonderful as the post. Indeed, in one of the comments, Bady sums up what I most respect in fiction far better than I ever have:

I adore, or, at least, I adored when I read it about ten years ago) to explore the idea of "great writers" and who has the authority to write about/represent particular cultures in writing -- the discussion in the comments section is as wonderful as the post. Indeed, in one of the comments, Bady sums up what I most respect in fiction far better than I ever have:

...what I find most interesting in Achebe is his attention not to questions of who is right and who is wrong (since every perspective is flawed and mediated) but his exploration of how official truths are produced, which TFA as novel becomes a vehicle for. Or, in Arrow of God

as novel becomes a vehicle for. Or, in Arrow of God , his interest in how official truths get subverted when they don’t “work” the way they’re supposed to. In both cases, it seems like he manages to make any conception of “representation” take on so much water, so fast, that you’re left, like Foucault reading criminology texts, scratching your head and trying to figure out how people come to believe the things they do, instead of trying to figure out what the correct belief should be.

, his interest in how official truths get subverted when they don’t “work” the way they’re supposed to. In both cases, it seems like he manages to make any conception of “representation” take on so much water, so fast, that you’re left, like Foucault reading criminology texts, scratching your head and trying to figure out how people come to believe the things they do, instead of trying to figure out what the correct belief should be.

It's not all about Africa and African lit -- Bady's interests are wide-ranging and eclectic -- but that's what first captured my interest and attention, so it's what I'm highlighting here. I was taken, too, with Bady's

explanation of the blog's title:

In Tanzania, you learn that you’re an mzungu when children shout “zunguzungu!” and follow you around, and in California you learn to forget because they aren’t there to remind you. But you still are, so I’ve kept the name, even though I’m now writing about other things. And I won’t define what it means, because you can if you want, and words aren’t so easily corralled into order as it might sometimes seem, thank goodness. And anyway, it’s not such a bad thing to be, really. They were delighted to see me, and I was delighted to see them, if not for the same reasons.

I learned a long time ago that I’m a white guy from the United States, long before I ever left Appalachia. But being called an Mzungu–for out of the mouths of children!–can teach you different things, if you let it. Too many people take the name Mzungu as an insult; but it isn’t, not exactly. Tanzanians sometimes use it as a compliment for other Tanzanians; wewe kizungu sana! It isn’t that either, not quite. Race is physicial, but “kizungu” is tabia or utamaduni, words that get mistranslated as culture or civilization, but mean something deeper about how and why people relate to other people the way that they do. Some people like to be called “Western,” and some people don’t; some people have that option and some people don’t. But I’ve taken the name zunguzungu for this blog not as a claim but as a provocation, and a reminder for myself. I’m really not sure what it means, on the deepest level, and I want to remember that ignorance. It also means many different things, so I want to remember that too. But whatever “zunguzungu” is, I know that I am it; the task, then, is to make that “it” into something good.

I could keep quoting all night. I won't. I have a z to keep working on before I let myself return to this here province. Meanwhile, you should be reading Aaron Bady.

(Oh, you want to know what I think of Coetzee's

Summertime

? Well, since I'm here already... It's magnificent and thought-provoking, of course, because I think Coetzee is just about the best living writer in the English language, at least among the living writers of English I know. It's been billed as the third in a trilogy of memoir-novels begun with

Boyhood

and continued with

Youth

, but though the "John Coetzee" of those books seems to be roughly the same creature as the "John Coetzee" of

Summertime, the book itself is more of a piece with

Dairy of a Bad Year [a book I think I underestimated when I first read it] and

Elizabeth Costello

in the ways it forces readers to become active, even self-aware participants in the meaning-making in a more insistant way than many other books -- indeed, it seems to me that Coetzee is using the fame he gained from winning a

second Booker Prize and then a

Nobel to question the whole idea of the writer as role model and authority -- an idea he's been questioning pretty much his entire career, but the changed and extraordinary circumstances of his life now give him some particularly powerful tools [in the form of readers' expectations and desires] to work with. I don't think it is a coincidence that

Disgrace was his last novel to have a traditional narrative structure [it being the work that got him his second Booker, and the first I have with the word "bestseller" emblazoned on the cover]. I also think

Summertime shows how vital the conversations and essays in

Doubling the Point are to understanding a lot of what Coetzee is up to, even now, nearly twenty years after that book was put together. Confession and complicity remain powerful concerns for him. More -- hopefully, much more -- on this subject anon...)

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 6/18/2009

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

zombies,

Coetzee,

Add a tag

J.M. Coetzee recently came back from the dead to read from his new book (link via Maud):

Seeing Coetzee read on Thursday night thus presented a spectacle to make any postmodern literary critic lick their chops: an almost pathologically private man reading his own "fictionalised memoir", with Summertime achieving a further distancing effect by means of the fact that the book takes the form of a series of interviews with people from Coetzee’s life carried out after Coetzee’s death.

Coetzee fans will remember that in the previous books in the trilogy,

Boyhood

and

Youth

, the young John Coetzee discovered a radioactive meteor in provincial South Africa and soon after began experiencing the distancing of signs from their signifiers. In search of signifiers less free-floating, he set out across the wilds of the veld and had many interesting encounters with metaphysical conceits that both tormented him and provided balm to his increasingly abjected soul. By the end of the second book, though, his quest seemed to have failed, as he was captured by an evil allegorist and tortured with harrowingly simplified logics that succeeded in revealing the death instinct to be the mask of symbolic order. All ambiguity appeared to be lost, killed in the dungeon of the allegorist. The author was finally

dead.

But wait! In the third installment, we discover that our intrepid hero has come back from the dead to seek revenge, justice, and contingent truths! Will he triumph over the textual practices of enemies more powerful than any he has encountered before? Will traditionalist gangsters plug him in the aporia? What are the interpretive implications of his mantra, "

They're coming for you, Elizabeth Costello!"

And most

shocking for Coetzee fans may be the scenes of their hero consuming dead flesh as he fuels himself for the final battle in what is sure to be hailed as the greatest novel since Samuel Beckett's

Malone Dies Again! Don't miss it!

First, Josipovici, now Coetzee -- Beckett's selected letters are getting reviewed by the best. Deservedly so.

are getting reviewed by the best. Deservedly so.

Coetzee uses the occasion of a review to give a fine overview of Beckett's life and thought during the 1930s, as reflected in the letters. For instance:

Migrations of artists are only crudely related to fluctuations in exchange rates. Nevertheless, it is no coincidence that in 1937, after a new devaluation of the franc, Beckett found himself in a position to quit Ireland and return to Paris. Money is a recurrent theme in his letters, particularly toward the end of the month. His letters from Paris are full of anxious notations about what he can and cannot afford (hotel rooms, meals). Though he never starved, he lived a genteel version of a hand-to-mouth existence. Books and paintings were his sole personal indulgence. In Dublin he borrows £30 to buy a painting by Jack Butler Yeats, brother of William Butler Yeats, that he cannot resist. In Munich he buys the complete works of Kant in eleven volumes.

What £30 in 1936 represents in today's terms, or the 19.75 francs that an alarmed young man had to pay for a meal at the restaurant Ste. Cécile on October 27, 1937, is not readily computed, but such expenditures had real significance to Beckett, even an emotional significance. In a volume with such lavish editorial aids as the new edition of his letters, it would be good to have more guidance on monetary equivalents. Less discretion about how much Beckett received from his father's estate would be welcome too.

A bit of internetting can answer some of the questions about money equivalents.

This currency converter, for instance, lets us know that the £30 Beckett spent on the Yeats painting equals about $2,880.15 today. Not a minor investment, and, indeed, it would have been nice information to have in the book. Nonetheless, as just about every reviewer, including Coetzee, has pointed out, the scholarly apparatus in the book is vast and in many ways astounding and overwhelming.

.jpg?picon=160)

By: Matthew Cheney,

on 4/6/2009

Blog:

The Mumpsimus

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Kenya,

books,

Africa,

teaching,

ramblings,

Coetzee,

Brian Evenson,

Uganda,

Noel Coward,

serial killers,

Joshi,

Bowles,

Joel Lane,

Aickman,

Beckett,

Josipovici,

Baingana,

Rhys,

Jedediah Berry,

Add a tag

One thing I love about blogs is seeing people discover books that have become so much a part of my own life that I develop the sense that everybody else on Earth has also read them, and so there's no need for me to talk about them, because we all know these are great books, right? It's nice to be reminded that this is a fantasy -- nice to see people suddenly fall in love with books I've known for a little while already.

The great and glorious Anne Fernald just posted a list of some books she's read lately with joy and happiness, and the two books on the list that I've read are ones I recommend without reservation: Tropical Fish by Doreen Baingana and Good Morning, Midnight

by Doreen Baingana and Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys.

by Jean Rhys.

I first heard about Tropical Fish when I was in Kenya for the SLS/Kwani conference and Doreen Baingana was part of a panel discussion; I found her captivating. Later, a Ugandan friend (who also told me about FEMRITE) exhorted me to read the book. I did. I exhort you to do the same.

I don't remember when I stumbled upon Good Morning, Midnight -- I feel like the battered, crumpled paperback I've got has been with me for years, but I know I read it only a handful of years ago. Few other books have affected the prose of my own writing as deeply. Much of what I've written, and even some of what I've published, I could call my pre-Rhys writing -- aspiring toward a sort of lyricism that now I have little interest in. Good Morning, Midnight offers, to my eye's ear, a prose that I would rank in its stark, precise beauty with that of Paul Bowles, J.M. Coetzee, and even, to some extent, Beckett.

Meanwhile, much like Anne, I've been reading a lot without writing about it. I've felt like I either didn't have much to say about what I've read, or what I'd have to say has already been said by plenty of people. Here, though, are some quick thoughts on some of what I've read over the last few weeks:

I was looking forward to Jedediah Berry's first novel, The Manual of Detection , with so much excitement that I may have slaughtered it with expectations. Some of Jed's short stories are among my favorites of recent years, and I had high hopes for the novel, but those hopes were never quite met. It was a brisk and sometimes exhilarating read, but ultimately felt whispy to me, especially in the last third, from which I ached for much more. Much more what? I don't know. But more.

, with so much excitement that I may have slaughtered it with expectations. Some of Jed's short stories are among my favorites of recent years, and I had high hopes for the novel, but those hopes were never quite met. It was a brisk and sometimes exhilarating read, but ultimately felt whispy to me, especially in the last third, from which I ached for much more. Much more what? I don't know. But more.

Similarly, I think Brian Evenson is one of the better contemporary American writers, and so my hopes for his new novel, Last Days , were unreasonably high. It's an interesting and sometimes harrowing book, but again I wasn't satisfied with it in the last third or so. (Matt Bell has written a comprehensive and thoughtful take on the novel here.) It's not that I didn't like either The Manual of Detection or Last Days -- I read them both, and neither ever really felt like a slog to get through -- but both left me unsatisfied, yearning for more complexity and depth and nuance and implication.

, were unreasonably high. It's an interesting and sometimes harrowing book, but again I wasn't satisfied with it in the last third or so. (Matt Bell has written a comprehensive and thoughtful take on the novel here.) It's not that I didn't like either The Manual of Detection or Last Days -- I read them both, and neither ever really felt like a slog to get through -- but both left me unsatisfied, yearning for more complexity and depth and nuance and implication.

Then one day the mail brought both The Letters of Noël Coward and The Letters of Samuel Beckett: Volume 1, 1929-1940

and The Letters of Samuel Beckett: Volume 1, 1929-1940 . I wondered what the mail gods were trying to tell me (one friend replied, when I mentioned the coincidence: "I think it means you are either: an absurd gayist ... or a flamboyant abusrdist. Possibly both." I'll try for both). The Coward was a review copy, the Beckett a book I splurged on for myself. I tried reading the former for a bit, because I do have a certain weakness for good ol' Noël, but the letters are presented amidst a narrative of Coward's life, and I found it annoying, so couldn't continue.

. I wondered what the mail gods were trying to tell me (one friend replied, when I mentioned the coincidence: "I think it means you are either: an absurd gayist ... or a flamboyant abusrdist. Possibly both." I'll try for both). The Coward was a review copy, the Beckett a book I splurged on for myself. I tried reading the former for a bit, because I do have a certain weakness for good ol' Noël, but the letters are presented amidst a narrative of Coward's life, and I found it annoying, so couldn't continue.

The Beckett is a masterpiece of editing, a feat of scholarship, and utterly fascinating. I devoured half of the big book in only a few days (then stopped, ready to go again on the second half very soon). Gabriel Josipovici reviewed it, so I have nothing else to say.

Partly because of my "Murder, Madness, Mayhem" class, I happened to read some Robert Aickman stories and became obsessed. I had last read Aickman when I was about 17 or so, and I had hated his stories. I thought they were the most boring, pointless things ever written by any human being ever, ever, ever. Ahhh, youth! "The Hospice" and "The Stains" are now stories I am simply in awe of. I quickly hunted up the only two relatively affordable Aickman collections available on the used book market: Cold Hand in Mine and Painted Devils

and Painted Devils . They are full of exactly what Aickman says they are full of: strange stories. Beautifully, alarmingly strange stories.

. They are full of exactly what Aickman says they are full of: strange stories. Beautifully, alarmingly strange stories.

Someone should publish an affordable paperback of Aickman's selected (or, be still my heart, collected!) stories. Tartarus Press published a two-volume collected stories, but it's going for at least $700 these days, and though I love Aickman, I can't spend $700 on him. Thus, I implore the publishing world to relieve my yearning and reprint a collection or two or eight of Aickman's stories in inexpensive editions! Someone? Anyone? Please? NYRB Books, I'm looking at you right now.....

Wanting to read some nonfiction about Aickman, I borrowed S.T. Joshi's The Modern Weird Tale: A Critique of Horror Fiction from a library and read the fairly astute chapter on Aickman. But I have to admit, my first thought on reading various parts of Joshi's book was, "What crawled up this guy's ass and died?" I know some people have thought the same about things I've written, so I didn't hold it against him. I was curious how Joshi is perceived within the horror community, though, because his rants against writers like Stephen King and Peter Straub seem so over-the-top to me that they actually work better as humor than as criticism, and he sometimes seems to get angry at writers for not fitting into his own narrow categories, for not agreeing with his (Lovecraftian) view of the universe, for not being more, well, Joshian. He has some fascinating things to say, but also ... not. Is he the Ezra Pound of genre criticism? The Cimmerian quotes Joel Lane (whose short stories

from a library and read the fairly astute chapter on Aickman. But I have to admit, my first thought on reading various parts of Joshi's book was, "What crawled up this guy's ass and died?" I know some people have thought the same about things I've written, so I didn't hold it against him. I was curious how Joshi is perceived within the horror community, though, because his rants against writers like Stephen King and Peter Straub seem so over-the-top to me that they actually work better as humor than as criticism, and he sometimes seems to get angry at writers for not fitting into his own narrow categories, for not agreeing with his (Lovecraftian) view of the universe, for not being more, well, Joshian. He has some fascinating things to say, but also ... not. Is he the Ezra Pound of genre criticism? The Cimmerian quotes Joel Lane (whose short stories I like quite a bit):

I like quite a bit):

[Joshi's] Lovecraft biography is a serious classic. Joshi’s recent book The Modern Weird Tale is a mixed bag, highly idiosyncratic and unfair, but full of good insights. His new book The Evolution of the Weird Tale, despite its grand title, is basically a collection of review articles; but it’s enormous fun and less narrow than some earlier Joshi stuff. The Weird Tale, published in 1990 and covering the weird fiction genre from Machen to Lovecraft, is ambitious and dynamic but heavy-handed and too fond of extreme statements. Behind the veils of academic objectivity, Joshi can be seen to be a volatile, short-tempered, aggressive and highly intense young man. He has mellowed a little since, though his sarcasm can still wither at forty paces.

As I prepared my class to watch an episode of

Dexter, I read around in

Jack the Ripper and the London Press

by L. Perry Curtis, Jr. and

Natural Born Celebrities: Serial Killers in American Culture

by David Schmid -- both well worth reading, rich with insights.

Nowadays, I'm mostly doing research about British imperialism and its connection to mystery and adventure fiction. Fascinating stuff, which will, I hope, bring a new project to fruition...

Early this week, I thought I'd write a little post about J.M. Coetzee's Life and Times of Michael K , since I just got finished teaching it in my Outsider course and wanted to preserve a few of the things I'd thought about -- each reading experience of the novel has been, for me, quite different. But then I got to thinking about futurist fiction in South Africa before the end of apartheid, since I had started doing some research on the subject recently (mostly spurred on by a footnote in David Attwell's J.M. Coetzee: South Africa and the Politics of Writing), digging up out-of-the-way articles and out-of-print books, and I thought, Well, I can put some of that into the post, since it's interesting, but I wanted to do more research before saying anything in public, but I didn't have time, and, well ... here we are. No post all week. But lemme tell ya, the one in my head, WOW! It's a doozy, you betcha!

, since I just got finished teaching it in my Outsider course and wanted to preserve a few of the things I'd thought about -- each reading experience of the novel has been, for me, quite different. But then I got to thinking about futurist fiction in South Africa before the end of apartheid, since I had started doing some research on the subject recently (mostly spurred on by a footnote in David Attwell's J.M. Coetzee: South Africa and the Politics of Writing), digging up out-of-the-way articles and out-of-print books, and I thought, Well, I can put some of that into the post, since it's interesting, but I wanted to do more research before saying anything in public, but I didn't have time, and, well ... here we are. No post all week. But lemme tell ya, the one in my head, WOW! It's a doozy, you betcha!

I do plan on writing an essay about such futurist South African fiction as Karel Schoeman's Promised Land , Nadine Gordimer's July's People

, Nadine Gordimer's July's People and A Sport of Nature

and A Sport of Nature , Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians

, Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians , and Mongane Serote's To Every Birth Its Blood(Contemporary Fiction Series)

, and Mongane Serote's To Every Birth Its Blood(Contemporary Fiction Series) ... but I need to read them all first.

... but I need to read them all first.

Until then, some humble and probably obvious notes on Michael K....

When Coetzee is at his best as a novelist -- Barbarians, Michael K., Disgrace,Elizabeth Costello -- there is simply no other living writer I would rather read. All of his other books at the very least reward the time spent reading them (I'm quite fond, too, of his memoirs, Boyhood

-- there is simply no other living writer I would rather read. All of his other books at the very least reward the time spent reading them (I'm quite fond, too, of his memoirs, Boyhood and Youth

and Youth ). As I read Michael K. this time, I tried to think about what it is in Coetzee's work that so appeals to me. It's no individual quality, really, because there are people who have particular skills that exceed Coetzee's. There are many writers who are more eloquent, writers with more complex and evocative structures, writers of greater imagination.

). As I read Michael K. this time, I tried to think about what it is in Coetzee's work that so appeals to me. It's no individual quality, really, because there are people who have particular skills that exceed Coetzee's. There are many writers who are more eloquent, writers with more complex and evocative structures, writers of greater imagination.

And then I realized that I was marking up my teaching copy of Michael K. as if I were marking up a poem. I looked, then, at my teaching copy of Disgrace, from when I used it in a class a few years ago. The same thing. Lots of circled words, lots of "cf."s referring me to words and phrases in other parts of the book. Lots of sounds building on sounds, rhythms on rhythms in a way that isn't particularly meaningful in itself, but that contributes to an overall tone-structure, a scaffold of utterance to hold up the shifting meanings of the story and characters.

The other writers I think of as doing this sort of thing -- Gaddis, DeLillo, and Pynchon come to mind, though more as 2nd-cousins than twin brothers -- do so on a larger, more baroque scale. Coetzee is closer to Beckett, but more concrete (less dense than early Beckett, less ethereal than later). The biggest influences on Coetzee, it seems from some of his interviews and essays, have been Kafka and Beckett, and if forced to say which writers of the last 100 years matter the most to me right now, I'd say, myself, Kafka and Beckett, with Coetzee somewhere close behind them, hand-in-hand with Paul Bowles, Virginia Woolf, and maybe a couple of others, depending on my mood. This says less about literature than it does about me, about what it is I look for in fiction -- there is a bleakness of vision to most of these writers, often a fierce anti-sentimentality (which, in their best works, does not preclude humanity or descend to the converse of sentimentality, macho frigidity), and a great depth of language within relatively compressed fictional forms. My love for this sort of writing is also my limitation as a reader; I am, I think, capable of appreciating the DeLillos, Gaddises, and Pynchons of the world, but I am not someone who can truly love their work. (Instead, I end up loving them for certain sentences and paragraphs. There are passages in Mason & Dixon, Underworld, and The Recognitions that reach toward the height of human accomplishment with language -- perhaps these are simply feasts too rich for my metabolism.) Similarly, many more lush or emotive writers are capable of effects I can notice and see as skillful, but ultimately they ... well, they make me gag.

Once I got past obsessing over why a book like Michael K. appeals to me so deeply, I was able to focus on other things. My students struggled with matching their expectations for what a novel should be and do to what this novel is and does, and much of our time in class was spent on finding patterns -- patterns create meaning, I told them, and so when you get stuck, look for patterns. I had them find passages in the novel having to do with time, fertility, authority, children, communication (speech, words), and places where characters talked about the meaning of things, or where they assigned meaning to things. I made them search through the book as if on a scavenger hunt (which proved difficult for most because they had read quickly and hadn't written anything in their texts, but working in groups they stumbled along). As they talked amongst each other, sharing discoveries, they found that the novel was not the amorphous, "pointless" thing they had perceived it as, but rather a web of repetitions and reiterations. If I'd truly been prepared, I would have then given them some words of Barry Lopez from the introduction to About This Life :

:

Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives.

Among other things, what we find in the patterns floating around the character of Michael K. are questions about what it even means to say "the character of Michael K.", because the story we are told (or, more accurately, stories) is one in which people impose meanings onto him and he resists them. As readers, our instincts encourage us to find meanings and apply them just as much as the other characters in the book do -- we want to sum him up in the mostly simplistically Freudian ways we can, which is how we read most narratives these days -- what motivates the characters, what secrets need to be revealed for them to overcome the obstacles in their lives, how can they come to peace with their childhoods, etc. We've been fed this predictable sort of psychodrama for at least a century now, and it fuels not just morning soap operas on tv, but most of the bourgeois literature of our era and many earlier eras (more often than not, good books are good in spite of their psychologizing).

Some critics have faulted

Michael K. for the second section, which, two-thirds of the way into the novel, stops everything and shifts the viewpoint. Suddenly we are outside K's point of view, looking at him through the notes of a doctor. When I first read the novel (ten years ago now), I, too, was thrown off by the second section, mostly because the first had so overwhelmed me with the vivid, visceral imagery created by perfectly ordinary words. The shift seemed like a cheat to me, as if Coetzee couldn't admit how powerful and evocative the first section was, or was afraid of it. Cynthia Ozick made

a good case against it:

If ''Life & Times of Michael K'' has a flaw, it is in the last-minute imposition of an interior choral interpretation. In the final quarter we are removed, temporarily, from the plain seeing of Michael K to the self-indulgent diary of the prison doctor who struggles with the entanglements of an increasingly abusive regime. But the doctor's commentary is superfluous; he thickens the clear tongue of the novel by naming its ''message'' and thumping out ironies. For one thing, he spells out what we have long ago taken in with the immediacy of intuition and possession. He construes, he translates: Michael K is ''an original soul . . . untouched by doctrine, untouched by history . . . evading the peace and the war . . . drifting through time, observing the seasons, no more trying to change the course of history than a grain of sand does.'' All this is redundant. The sister- melons and the brother-pumpkins have already had their eloquent say. And the lip of the child kept from its mother's milk has had its say. And the man who grows strong and intelligent when he is at peace in his motherland has had his say.

Where I differ with Ozick now is that I don't think the doctor does understand K, and I don't think the explanation he offers is persuasive (it would be were K a relative of

Forrest Gump, perhaps). The doctor ascribes a meaning to K based on his own desires and disappointments, and it is the process of meaning-making that we follow in the second section, and it is revelatory and chastening, because who among us has resisted the same urges while reading the first section? It's important that people have misnamed K by this point, calling him "Michaels". He cannot be bound up in a meaning anymore than he can be bound up in an internment camp, and they mistake his meaning as they mistake his name. We'll get no sustenance by cannibalizing him for our metaphysics; he's just skin and bones.

The last fifteen pages of the book return us to K's point of view and his peregrinations. Now we as readers are more prepared. We should know by now to be suspicious of our impulses, to know that what we want to do says more about us and our world than about K and his.

The movement of the novel is, broadly speaking, from city to countryside to city to countryside -- except the last movement to countryside is imagined. K lies on a pile of flattened cardboard boxes in the little closet room where his mother had lived in the city, and he's probably dying, and he thinks back to what has happened to him and where he has been, and he begins ascribing more meaning to himself than he ever has before, a meaning built from references to a life lived in cages and to gardening and staying close to the ground (shades of

Being There, but with more complexity, sophistication, and depth). A motif of things underground fills the book -- sometimes from urges and ideas that are paranoid and crazy, sometimes from ones eminently practical -- and every reader sees all the attention given to seeds and growing things, to life that sprouts out of the ground. The symbolism is obvious, and I think Coetzee knows this, because it's not for us that he has created these particular symbols, but for the characters in the book (Michael K. particularly) who need something to grasp in their search for meaning.

On the penultimate page, K thinks in a parenthesized paragraph:

(Is that the moral of it all, he thought, the moral of the whole story: that there is time enough for everything? Is that how morals come, unbidden, in the course of events, when you least expect them?)

The tone is uncertain, and I think we should be wary of accepting the moral K thinks he has found. It may be one of the meanings available from this life, but even K's life is richer than to be summed up in a moral. We cheapen existence when we simplify it into morals and mottos and

triangles. We need resonant imagery to replace our slogans, charts, and graphs -- and so

Life and Times of Michael K ends with a beautiful and perplexing image: Michael imagines a companion (one that bears some similarity to the doctor's first impression of Michael himself), and he imagines the farm in the country, and he imagines a well and a teaspoon and just enough pure water to sustain life. There is meaning there, but it must be felt in the rhythms of the word and thought, it must be welcomed into the mind like a koan or a magical riddle that asks for no solution. As long as he keeps from solving the puzzle of himself, Michael K will live.

This is a book that will need to be reread. Until then, some notes.

Diary of a Bad Year is immediately impressive simply because it isn't incoherent. That may sound like faint praise, but in this case it is not, because J.M. Coetzee has decided to structure this novel as three voices speaking, mostly, at once. The first pages are split between a top section and a bottom section, with the top devoted to short essays about current events and the bottom devoted to the diary of the writer of those essays, a South African novelist known around his apartment building in Australia as "Señor C". On page 25, a third section is added to each page: the diary of a woman named Anya, who becomes the typist for the novelist's opinions.

is immediately impressive simply because it isn't incoherent. That may sound like faint praise, but in this case it is not, because J.M. Coetzee has decided to structure this novel as three voices speaking, mostly, at once. The first pages are split between a top section and a bottom section, with the top devoted to short essays about current events and the bottom devoted to the diary of the writer of those essays, a South African novelist known around his apartment building in Australia as "Señor C". On page 25, a third section is added to each page: the diary of a woman named Anya, who becomes the typist for the novelist's opinions.

Such a structure is a recipe for confusion, but it is a testament to Coetzee's skill that the novel is always readable and often compelling. We have the choice of sticking with one of the sections for as long as we want to keep flipping pages, or we can read the pages top to bottom, drifting between voices. I mostly did the latter, even when, as happens toward the middle of the book, the sections began to stray parts of their sentences across multiple pages, providing no convenient spot to pause.

In his insightful New Yorker review, James Wood says, "In truth, one reads the top section of each page with mounting excitement, and the bottom two sections rather dutifully," but my experience was exactly the opposite -- the "Strong Opinions" (as, a la Nabokov they will be called when translated and published in Germany) are interesting enough, but few of them are particularly incisive, and many are quite ephemeral, rushing through the current of the events they respond to. Which is, it seems to me, the point. Novelists are not inherently better opinionators than any other pundit or person. Señor C is writing outside his realm of greatest competence. The meaning of his essays lies not in what they say, but in how they fit into the story of Diary of a Bad Year, for which they are simultaneously the motivating material and the byproduct. It is not a novel of ideas so much as it is a novel depicting the inspiration and effect of ideas, their predictable limits and unpredictable force.

they will be called when translated and published in Germany) are interesting enough, but few of them are particularly incisive, and many are quite ephemeral, rushing through the current of the events they respond to. Which is, it seems to me, the point. Novelists are not inherently better opinionators than any other pundit or person. Señor C is writing outside his realm of greatest competence. The meaning of his essays lies not in what they say, but in how they fit into the story of Diary of a Bad Year, for which they are simultaneously the motivating material and the byproduct. It is not a novel of ideas so much as it is a novel depicting the inspiration and effect of ideas, their predictable limits and unpredictable force.

Coetzee is also once again playing with our desire to match writer to writings. He's done this from his very first book, Dusklands , and Foe

, and Foe and The Master of Petersburg

and The Master of Petersburg fictionalized and riffed on the lives of Daniel DeFoe and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, respectively, to examine the connections between writers and texts, readers and what they read, the world and the book. Recently, Elizabeth Costello

fictionalized and riffed on the lives of Daniel DeFoe and Fyodor Dostoyevsky, respectively, to examine the connections between writers and texts, readers and what they read, the world and the book. Recently, Elizabeth Costello and Slow Man dared us to wonder even more about the connections between Coetzee, his characters, and their opinions. Diary of a Bad Year feels, in some ways, like a summing up of those two books, an attempt to discover a post-Elizabeth Costello world.

and Slow Man dared us to wonder even more about the connections between Coetzee, his characters, and their opinions. Diary of a Bad Year feels, in some ways, like a summing up of those two books, an attempt to discover a post-Elizabeth Costello world.

Diary of a Bad Year, though, is a much less frustrating book to read than many of its predecessors, and this is, in some ways, its weakness. Coetzee's least traditional books frustrate us by jumping out of the way of our genre and narrative expectations; his more straightforward books frustrate us with their moral complexity, their brutal details, their cold eye toward a world of everyday atrocities. Some of Coetzee's books frustrate us by appearing to be allegories and then refusing to be so; some frustrate by undermining our sense of history and reality in ways that can't be summed up in soundbytes; some frustrate by objectively presenting deeply flawed and even repulsive protagonists. It is a productive and exciting frustration, the sort of frustration the greatest literature provides -- an effect that cannot be summed up, but only pointed toward and experienced. For a reader not much interested in the stories Diary of a Bad Year has to tell, I expect the book is more numbing than frustrating; for a reader, like me, who finds it all quite interesting there is no frustration at all -- this is probably as close to a page-turning romp as Coetzee is ever likely to write. The effect, then, of reading the book is a perfectly pleasurable one, but Diary of a Bad Year is less of a provocation to thought and feeling than Coetzee's other, more unsettling, books.

Nonetheless, Diary of Bad Year is an extraordinary book, and even if I think it offers less than some of Coetzee's best work, that is very light criticism: few living writers possess Coetzee's mix of intelligence and skill, and he is one of the few writers I can think of where I can't imagine ever calling any book his "worst", even though, as with any writer, he has books that are better than others. As I said at the beginning, this one cries out for rereading, and I look forward to entering its pages again.

With Memorial Day weekend here in the United States, accompanied by warm weather almost country-wide, folks will be celebrating the unofficial start of summer. But summer doesn't truly arrive for another three weeks or so, and so I thought I'd post a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins to remind us all to enjoy the spring.

Hopkins was a Jesuit priest who wrote in traditional forms during the Victorian era in England. However, he used fresh imagery and techniques like sprung rhythm (echoing actual conversational tones instead of adhering rigorously to iambic pentameter or some other set metre). Here is a lovely sonnet in an italianate or Petrarchan form (abba/abba/cdcdcd) for you:

Spring

Nothing is so beautiful as spring—

&emsp When weeds, in wheels, shoot long and lovely and lush;

&emsp Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens, and thrush

Through the echoing timber does so rinse and wring

The ear, it strikes like lightnings to hear him sing;

&emsp The glassy peartree leaves and blooms, they brush

&emsp The descending blue; that blue is all in a rush

With richness; the racing lambs too have fair their fling.

What is all this juice and all this joy?

&emsp A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden.—Have, get, before it cloy,

&emsp Before it cloud, Christ, lord, and sour with sinning,

Innocent mind and Mayday in girl and boy,

&emsp Most, O maid’s child, thy choice and worthy the winning.

And should you, by chance, prefer something more in keeping with the nature of Memorial Day, once called Decoration Day, and established to remember those who've died in the service of the United States, then I'll point you to some war poems -- even though the poems I'm pointing you to are by men who were English and Canadian.

I was completely unaware of the existence of the book; I will have to find a copy. Thank you! All the recommendations I've gotten from you in the past have been good ones.

You forget that I once recommended 1,001 Things to Do with an Artichoke Heart, which you told me got a little repetitive after #723...

I bet you'll like Schreiner, though, and given how much Greek and Latin you've made your way through, I doubt the philosophical passages will seem too dull! ;-)