new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: border, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: border in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Eleanor Jackson,

on 9/17/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Africa,

soldiers,

race,

African,

British,

Europe,

wall,

Rome,

frontier,

Romans,

African History,

border,

Roman Britain,

British history,

guard,

*Featured,

Moors,

Game of Thrones,

Classics & Archaeology,

auxilia,

emporer,

Hadrian’s Wall,

roman history,

Add a tag

Hadrian’s Wall has been in the news again recently for all the wrong reasons. Occasional wits have pondered on its significance in the Scottish Referendum, neglecting the fact that it has never marked the Anglo-Scottish border, and was certainly not constructed to keep the Scots out. Others have mistakenly insinuated that it is closed for business, following the widely reported demise of the Hadrian’s Wall Trust. And then of course there is the Game of Thrones angle, best-selling writer George R R Martin has spoken of the Wall as an inspiration for the great wall of ice that features in his books.

Media coverage of both Hadrian’s Wall Trust’s demise and Game of Thrones’ rise has sometimes played upon and propagated the notion that the Hadrian’s Wall was manned by shivering Italian legionaries guarding the fringes civilisation – irrespective of the fact that the empire actually trusted the security of the frontier to its non-citizen soldiers, the auxilia rather than to its legionaries. The tendency to overemphasise the Italian aspect reflects confusion about what the Roman Empire and its British frontier was about. But Martin, who made no claims to be speaking as a historian when he spoke of how he took the idea of legionaries from Italy, North Africa, and Greece guarding the Wall as a source of inspiration, did at least get one thing right about the Romano-British frontier.

There were indeed Africans on the Wall during the Roman period. In fact, at times there were probably more North Africans than Italians and Greeks. While all these groups were outnumbered by north-west Europeans, who tend to get discussed more often, the North African community was substantial, and its stories warrant telling.

Perhaps the most remarkable tale to survive is an episode in the Historia Augusta (Life of Severus 22) concerning the inspection of the Wall by the emperor Septimius Severus. The emperor, who was himself born in Libya, was confronted by a black soldier, part of the Wall garrison and a noted practical joker. According to the account the notoriously superstitious emperor saw in the soldier’s black skin and his brandishing of a wreath of Cyprus branches, an omen of death. And his mood was not further improved when the soldier shouted the macabre double entendre iam deus esto victor (now victor/conqueror, become a god). For of course properly speaking a Roman emperor should first die before being divinized. The late Nigerian classicist, Lloyd Thompson, made a powerful point about this intriguing passage in his seminal work Romans and Blacks, ‘the whole anecdote attributes to this man a disposition to make fun of the superstitious beliefs about black strangers’. In fact we might go further, and note just how much cultural knowledge and confidence this frontier soldier needed to play the joke – he needed to be aware of Roman funerary practices, superstitions, and the indeed the practice of emperor worship itself.

Why is this illuminating episode not better known? Perhaps it is because there is something deeply uncomfortable about what could be termed Britain’s first ‘racist joke’, or perhaps the problem lies with the source itself, the notoriously unreliable Historia Augusta. And yet as a properly forensic reading of this part of the text by Professor Tony Birley has shown, the detail included around the encounter is utterly credible, and we can identify places alluded to in it at the western end of the Wall. So it is quite reasonable to believe that this encounter took place.

Not only this, but according to the restoration of the text preferred by Birley and myself, there is a reference to a third African in this passage. The restoration post Maurum apud vallum missum in Britannia indicates that this episode took place after Severus has granted discharge to a soldier of the Mauri (the term from which ‘Moors’ derives). And has Birley has noted, we know that there was a unit of Moors stationed at Burgh-by-Sands on the Solway at this time.

Sadly, Burgh is one of the least explored forts on Hadrian’s Wall, but some sense of what may one day await an extensive campaign of excavation there comes from Transylvania in Romania, where investigations at the home of another Moorish regiment of the Roman army have revealed a temple dedicated to the gods of their homelands. Perhaps too, evidence of different North African legacies would emerge. The late Vivian Swann, a leading expert in the pottery of the Wall has presented an attractive case that the appearance of new forms of ceramics indicates the introduction of North African cuisine in northern Britain in the second and third centuries AD.

What is clear is that the Mauri of Burgh-by-Sands were not the only North Africans on the Wall. We have an African legionary’s tombstone from Birdoswald, and from the East Coast the glorious funerary stela set up to commemorate Victor, a freedman (former slave) by his former master, a trooper in a Spanish cavalry regiment. Victor’s monument now stands on display in Arbeia Museum at South Shields next to the fine, and rather better known, memorial to the Catuvellunian Regina, freedwoman and wife of Barates from Palmyra in Syria. Together these individuals, and the many other ethnic groups commemorated on the Wall, remind us of just how cosmopolitan the people of Roman frontier society were, and of how a society that stretched from the Solway and the Tyne to the Euphrates was held together.

The post African encounters in Roman Britain appeared first on OUPblog.

by Ernest Hogan

When I wrote about Disney’s The Three Caballeros a while back, Tom Miller, author of On the Border and Revenge of the Saguaro told me I should look into the Roy Rogers movie, Hands Across the Border. He didn’t know if the State Department had anything to do with it, but there was Chicanonautica material there.

When I wrote about Disney’s The Three Caballeros a while back, Tom Miller, author of On the Border and Revenge of the Saguaro told me I should look into the Roy Rogers movie, Hands Across the Border. He didn’t know if the State Department had anything to do with it, but there was Chicanonautica material there.

I've always liked the Roy Rogers universe. It’s full of happy trails, and animals that are so intelligent you expect them to talk. It also takes place in time warp: stagecoaches coexist with trucks, jeeps, and atom bombs. It’s a kind of 20th century American dreamtime where the past is upgraded for the newfangled reality. And it often gets downright surreal.

Hands Across the Border is so surreal it should be considered a precursor to the acid western subgenre.

Hands Across the Border is so surreal it should be considered a precursor to the acid western subgenre.

It begins with a song, “Easy Street.” Roy sings it while riding into the town of Buckaroo, as he passes signs saying: CHECK YOUR CARES HERE AT THE CITY LIMITS AND RIDE ON INTO PARADISE and BEWARE TRAMPS, MOUNTEBANKS, GAMBLERS, SCALLYWAGS AND THIEVES THERE IS ONLY ONE PLACE IN TOWN WHERE YOU ARE WELCOME OUR JAIL! All while the lyrics declare that he doesn’t need money, and “Have you ever seen a happy millionaire?”

Did Sheriff Joe Arpaio ever see this?

Roy’s a saddle bum, or migrant worker, looking to earn his keep by wrangling horses and singing. And he does a lot of both as he saunters into a plot that's mostly an excuse to lead into the songs. Trigger accidentally kills the owner of the ranch, then encourages Roy to convince the owner’s daughter to keep the ranch from getting into the hands of the Bad Guy. Animals often act as spirit guides in the Roy Rogers universe.

Like The Three Caballeros, the story doesn’t directly have a “We gotta make friends with Latinos to defeat the Nazis” theme. Duncan Renaldo -- later know as The Cisco Kid on television -- is the ranch foreman, who orders around the Anglo cowboys, but nothing is really made of it. If there was any guidance from the State Department, it’s in the musical numbers. This really kicks in at a fiesta in the Renaldo characters’ town -- they don’t mention which side of the border it’s on.

There are muchas señoritas at the fiesta. Or at least Hollywood starlets in the appropriate regalia -- at least one was platinum blonde. And here we find a serious connection to The Three Caballeros, one of the señoritas sing “Ay, Jalisco, no te rajes!” song by Manuel Esperón, with Spanish lyrics by Ernesto Cortázar Sr. that was originally released in a 1941 film of the same name starring Jorge Negrete. Hands Across the Border was released on January 5, 1944. On December 21, 1944, The Three Caballeros premiered in Mexico City, featuring Esperón’s music with English lyrics by Ray Gilbert, making it into “The Three Caballeros.”

There are muchas señoritas at the fiesta. Or at least Hollywood starlets in the appropriate regalia -- at least one was platinum blonde. And here we find a serious connection to The Three Caballeros, one of the señoritas sing “Ay, Jalisco, no te rajes!” song by Manuel Esperón, with Spanish lyrics by Ernesto Cortázar Sr. that was originally released in a 1941 film of the same name starring Jorge Negrete. Hands Across the Border was released on January 5, 1944. On December 21, 1944, The Three Caballeros premiered in Mexico City, featuring Esperón’s music with English lyrics by Ray Gilbert, making it into “The Three Caballeros.”

Cultural appropriation? The State Department in Hollywood? Or is this tune just that catchy?

The Mexicans in the town are supposed to help the ranch train the horses for a “government contract” in some way, buy it’s not shown. The military and the war aren’t mentioned. This is a spectacular race/torture test that the horses -- Trigger included -- are put through that includes explosions and a “simulated gas attack.”

I don’t think poison gas was used in the Second World War. What war are these horses going to be used in? We’re in the time warp again. Is this an alternate universe? On does it take place on a future, terraformed Mars?

This leads into an incredible finale. The opening song declares “We don’t have to flaunt our egos, amigos.” For about fifteen minutes there’s an all-singing, all-dancing recombocultural mashup of cowboy songs, Mexican Music (including an English translation of “Ay, Jalisco, no te rajes!”), and jazz on a stage with crossed Mexican and American flags, and a white line to represent the border. There’s also a violin and a female singer that sound like theremins. And three guys in dresses.

It’s as if Guillemo Gómez-Peña and La Pocha Nostra were doing a time travel gig in the Forties

With Latinos becoming the majority in California, and elections coming up, maybe double features of Hands Across the Border and The Three Caballeros should be encouraged.

Ernest Hogan had a Roy Rogers lunch pail in grade school. He lives in the Wild West, where life constantly reminds him that reality is stranger than science fiction.

By: JonathanK,

on 2/2/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

US,

Oxford,

mexico,

Current Affairs,

immigration,

Geography,

border,

Berlin Wall,

Tijuana,

*Featured,

Mexican-American War,

Guadalupe Hidalgo,

Michael Dear,

Polk,

Third Nation,

nafta,

Add a tag

By Michael Dear

Not long ago, I passed a roadside sign in New Mexico which read: “Es una frontera, no una barrera / It’s a border, not a barrier.” This got me thinking about the nature of the international boundary line separating the US from Mexico. The sign’s message seemed accurate, but what exactly did it mean?

On 2 February 1848, a ‘Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement’ was signed at Guadalupe Hidalgo, thus terminating the Mexican-American War. The conflict was ostensibly about securing the boundary of the recently-annexed state of Texas, but it was clear from the outset that US President Polk’s ambition was territorial expansion. As consequences of the Treaty, Mexico gained peace and $15 million, but eventually lost one-half of its territory; the US achieved the largest land grab in its history through a war that many (including Ulysses S. Grant) regarded as dishonorable.

In recent years, I’ve traveled the entire length of the 2,000-mile US-Mexico border many times, on both sides. There are so many unexpected and inspiring places! Mutual interdependence has always been the hallmark of cross-border communities. Border people are staunchly independent and composed of many cultures with mixed loyalties. They get along perfectly well with people on the other side, but remain distrustful of far-distant national capitals. The border states are among the fastest-growing regions in both countries — places of economic dynamism, teeming contradiction, and vibrant political and cultural change.

A small fence separates densely populated Tijuana, Mexico, right, from the United States in the Border Patrol’s San Diego Sector.

Yet the border is also a place of enormous tension associated with undocumented migration and drug wars. Neither of these problems has its source in the borderlands, but border communities are where the burdens of enforcement are geographically concentrated. It’s because of our country’s obsession with security, immigration, and drugs that after 9/11 the US built massive fortifications between the two nations, and in so doing, threatened the well-being of cross-border communities.

I call the spaces between Mexico and the US a ‘third nation.’ It’s not a sovereign state, I realize, but it contains many of the elements that would otherwise warrant that title, such as a shared identity, common history, and joint traditions. Border dwellers on both sides readily assert that they have more in common with each other than with their host nations. People describe themselves as ‘transborder citizens.’ One man who crossed daily, living and working on both sides, told me: “I forget which side of the border I’m on.” The boundary line is a connective membrane, not a separation. It’s easy to reimagine these bi-national communities as a ‘third nation’ slotted snugly in the space between two countries. (The existing Tohono O’Odham Indian Nation already extends across the borderline in the states of Arizona and Sonora.)

But there is more to the third nation than a cognitive awareness. Both sides are also deeply connected through trade, family, leisure, shopping, culture, and legal connections. Border-dwellers’ lives are intimately connected by their everyday material lives, and buttressed by innumerable formal and informal institutional arrangements (NAFTA, for example, as well as water and environmental conservation agreements). Continuity and connectivity across the border line existed for centuries before the border was put in place, even back to the Spanish colonial era and prehistoric Mesoamerican times.

Do the new fortifications built by the US government since 9/11 pose a threat to the well-being of borderland communities? Certainly there’s been interruptions to cross-border lives: crossing times have increased; the number of US Border Patrol ‘boots on ground’ has doubled; and a new ‘gulag’ of detention centers has been instituted to apprehend, prosecute and deport all undocumented migrants. But trade has continued to increase, and cross-border lives are undiminished. US governments are opening up new and expanded border crossing facilities (known as ports of entry) at record levels. Gas prices in Mexican border towns are tied to the cost of gasoline on the other side. The third nation is essential to the prosperity of both countries.

So yes, the roadside sign in New Mexico was correct. The line between Mexico and the US is a border in the geopolitical sense, but it is submerged by communities that do not regard it as a barrier to centuries-old cross-border intercourse. The international boundary line is only just over a century-and-a-half old. Historically, there was no barrier; and the border is not a barrier nowadays.

The walls between Mexico and the US will come down. Walls always do. The Berlin Wall was torn down virtually overnight, its fragments sold as souvenirs of a calamitous Cold War. The Great Wall of China was transformed into a global tourist attraction. Left untended, the US-Mexico Wall will collapse under the combined assault of avid recyclers, souvenir hunters, and local residents offended by its mere presence.

As the US prepares once again to consider immigration reform, let the focus this time be on immigration and integration. The framers of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo were charged with making the US-Mexico border, but on this anniversary of the Treaty’s signing, we may best honor the past by exploring a future when the border no longer exists. Learning from the lives of cross-border communities in the third nation would be an appropriate place to begin.

Michael Dear is a professor in the College of Environmental Design at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Why Walls Won’t Work: Repairing the US-Mexico Divide (Oxford University Press).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “Third Nation” along the US-Mexico border appeared first on OUPblog.

La Bloga readers have various reasons for coming here, not the least of which is news we share from the Spanish-speaking world--from Spain's Semana Negra to cultural news from all over the Southwest. Despite being primarily an arts/literary blog, real-world events necessarily affect our art and how we live in each of our niches.

La Bloga readers have various reasons for coming here, not the least of which is news we share from the Spanish-speaking world--from Spain's Semana Negra to cultural news from all over the Southwest. Despite being primarily an arts/literary blog, real-world events necessarily affect our art and how we live in each of our niches.

The Internet, the WWW have provided us with floods of information--as countless as the over a billion Tweets or two hundred million blogs in existence (incl. Chinese). But the reliability of news and searches for "the truth" threaten to be buried by the staggering number of pieces out there. At the same time, mainstream sources of reliable journalism are declining. We the public, Chicano and otherwise, don't necessarily know as much as we once did.

For instance, how many know there have been at least ten suicides at Ft. Hood this year, an increase in domestic violence on-base and a rise in local crime? And who in the world of journalism is analyzing that for us and tying it to Obama's adding another 40,000 troops to "our" wars?

Information on Mexico and the shared border is important to us, not only because of our proximity or cultural ties, but the nature of that border is changing. Narco violence has crossed the river and no one can say how far north it will travel or how it might change our lives in Phoenix, San Antonio and even Denver.

None of this relates to you? Heading south of the border for an affordable vacation soon? Do you know which beaches are hygienically dangerous, unfit for swimming?

Are you an academic whose dissertation or published piece suffers because your pocho Spanish won't let you navigate la idioma journalistic waters?

Or are you in education and public service where you daily work with Mexican immigrants, but lack info about what it is that made them leave their mother country?

I speak only for myself when I say that my world revolves around the Southwest. I tend not to realize I need to encompass more to understand how and why things are transforming around me.

Luckily, years ago I found Frontera NorteSur. Their purpose: "FNS provides on-line news coverage of the US-Mexico border." They do this by analyzing and summarizing U.S., Me

Luckily, years ago I found Frontera NorteSur. Their purpose: "FNS provides on-line news coverage of the US-Mexico border." They do this by analyzing and summarizing U.S., Me

By: msedano,

on 11/10/2009

Blog:

La Bloga

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

short stories,

Texas,

poems,

csula,

Daniel Cano,

veterans day,

border,

call for papers,

octavio paz,

obregon monument,

congressional medal of honor,

death and the american dream,

Add a tag

Literary El Paso. Marcia Hatfield Daudistel, ed. Ft Worth TX: 2009.

ISBN 978-0-87565-387-7

Michael Sedano

In an era of ebooks and Kindles, iPhones, Blackberries and all manner of text-delivering digital device,

Literary El Paso seems a throwback to an earlier  era and a substantial reminder why one enjoys reading printed books in a cozy chair. Undeniably, portability is one advantage electronic devices have over the printed page. Whip out that iPhone while waiting for the bus and read to your heart’s content. Your heart. Me, I’m sure if I haul around this volume I either will forget my reading anteojos at home, or remember the lentes but set the book down somewhere and forget it. They say the memory’s the second thing to go and I do not remember the first.

era and a substantial reminder why one enjoys reading printed books in a cozy chair. Undeniably, portability is one advantage electronic devices have over the printed page. Whip out that iPhone while waiting for the bus and read to your heart’s content. Your heart. Me, I’m sure if I haul around this volume I either will forget my reading anteojos at home, or remember the lentes but set the book down somewhere and forget it. They say the memory’s the second thing to go and I do not remember the first.

Texas Christian University Press printed Literary El Paso’s 572 pages, plus xxiv front material, on a 7” x 10” page, giving the volume a comfortable heft and a shape that opens just right to fit a reader’s lap. The serifed font-- is it “Centaur” so highly praised in Carl Hertzog’s essay on page 9?-- is uncomfortably tiny for my eyes, but the typesetter’s justification spreads out individual letters so none touch neighbors (except in a couple of spots), and generous line spacing spreads the text across and down the page creating ample white space for maximal legibility. Once you’ve gotten hands on your own copy of Daudistel’s collection, you’ll likely agree Literary El Paso qualifies as a Morris Chair book.

Upon scanning Literary El Paso’s table of contents and paging serendipitously through the volume, readers will discover the editor’s liberal sense of “literary” as encompassing a wide variety of writing, from poetry to journalism to footnoted historical writing to fiction to essay. Indeed, Daudistel observes in her Introduction that “all writing coming out of a region is, in fact, the literature of that region” and that's what she's included, a rich potpourri of flavors.

Given such a cafeteria plan, readers may elect to browse the collection, not read it at a sitting. Daudistel’s made that easy by assembling her material into three themes. It’s a sensible organization that lends itself to part-by-part enjoyment. Part I, “The Emergent City / La Ciudad Surge”, opens with a cowboy fragment and features historians and journalists. Part II, calls itself “The People, La Gente”, and features a preponderance of Latina Latino writers, and fiction. Part III, “This Favored Place / Lugar Favorecido”, features poets and essays. The collection includes unpublished works from John Rechy, Ray Gonzalez and Robert Seltzer.

Given the pedo that erupted last Tuesday in Sergio Troncoso’s essay, Is the Texas Library Association excluding Latino writers?, Seltzer’s apologia for his father, Chester Seltzer AKA “Amado Muro” constitutes a mixed bag of biography and sympathetic character assassination, but not a defense for Seltzer père’s cultural appropriation--perhaps “reverse assimilation”-- of a Mexicano identity and his subsequent lionizing as a Chicano writer. Literary El Paso is silent about the controversy—see Manuel Ramos’ 2005 column for a usef

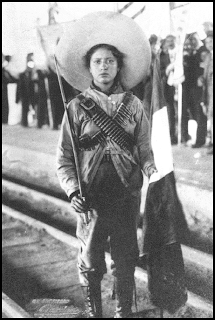

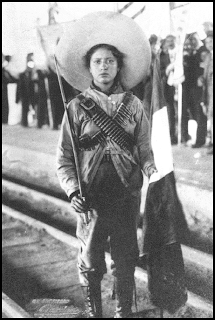

Unknown Soldaderas - Mexican Revolution

Porfirio Dias was Mexico’s president for 30 years following centuries of occupation, colonization, uprisings, invasions by Spain and France, and war with the United States. Dias’ autocratic regime gave rise to a new, industrialized Mexico, made possible by exploiting the majority of the people, stripping them of human rights while Dias built political power and personal wealth. Those who suffered most were the poor, the laborers, indios and women. In 1895, civil code was passed which severely restricted Mexican women to a life of serving their husbands, their families, and the Catholic Church.

The country was divided on these and other issues and Mexico fell into a ten-year period of chaos, with back-to-back political coups and foreign intervention. But, through the shifts in power, peasants gathered together to create a land that could serve all of Mexico’s people, including her women.This presented a conflict between traditional women who enjoyed their more domestic, subservient roles and an emerging feminism completely unknown in Mexico before. It became one of the underlying principles of the Mexican Revolution and the subject of one of the great reforms to arise from this period.

The women who stood up for higher ideals and demanded change were extraordinary, particularly given their social position and their time in history. They joined the Revolution, demanding reform across a country in disarray. Some became political voices, journalists who wrote articles opposing the tyranny of the ruling class. Some became nurses treating wounded revolutionary soldiers. Others served as spies or procured provisions for the small bands of peasants who continued fighting for freedom from 1910 until well after 1920. A few picked up weapons and joined forces, with Zapata in the south or Villa in the north, to fight along side the men. They became known as las soldaderas.

My mother, now in her late eighties, recalled the stories from her childhood in Mexico of a mysterious woman her Mama hated, a woman who came to their house to see the son she had left behind. Her name was Soledad.

For years, Soledad was described by my grandmother as a reckless harlot who irresponsibly left her child in the care of others so she could follow the revolutionary soldiers. To my grandmother, who could only view the events through the lens of her traditional upbringing, it was disgraceful. And, for more than a lifetime, only one side of the story was told. Finally, decades later, when my mother researched Mexican history, another story, long forgotten, materialized. This is my mother, Gloria's, recollection.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was born in 1921 but I can remember from about the age of 4, our life in Mexico. Papa’s name was Juan. He was born in Linares, Mexico, located about 130 km from Monterrey City in the State of Nuevo Leon.

Juan

JuanHe was orphaned in early childhood and sent to the seminary where he got an education. He was a newspaper reporter, book binder and writer. He was also an amateur ‘novillero,’ a novice bullfighter who fights young bulls. He had a younger sister, Soledad.

My parents settled in Monterrey once they were married. Mama was quite young, about 13. In the early years of the marriage, Mama – still a child herself, loved dressing up in beautiful clothes - taffeta dresses in popular styles of the time, fur coats and gold jewelry. She wore them on Sunday outings. Papa was very active in social clubs, sports and celebrations around town. Mama, beautiful and proud, saw her life as sophisticated and special, the life she was born to live.

We had 2 maids- one to care for us children, the other to cook and clean. Our house was always spotless and it seemed very grand. There was a pond with fine little pebbles inside the house, and here I could play for hours as a child. In the back yard was a beautiful garden. We seldom interacted with Mama but rather with my Nana, because proper women of class did not bother with domestic chores. When I was bathed by my Nana, dried with clean sheets, dressed in a hand- embroidered slip, I felt like a princess.

Gloria, age 4

Gloria, age 4

The few memories of going out with Mama were of going to the tailor for new clothes of fine materials, fur trim, and adornments. Mama always wore jewels and lace and very delicate clothing. We children always had to be dressed up as well. We were like her little dolls.

The biggest problem in Mama’s life was her sister-in-law, Soledad. At the age of about 17, Soledad had become a ‘Villista,’ one of the volunteers supporting Pancho Villa in the Revolution. This was a great embarrassment to Mama. To make matters worse, Soledad fell in love with a French soldier and bore their son, Alfonso. But, instead of coming home and managing her responsibilities, Soledad continued fighting the war. Alfonso lived with us.

Between battles, Soledad nursed the wounded or went begging for food and supplies, not seeing her son for months. They say that that she would sneak to our house at night, all filthy and hungry, and want to see Alfonso. She didn’t bring money or food, and even asked for provisions to take back with her. Mama hated her for this.

Mama was not political. She enjoyed her role, surrounded by domestic affluence and security. What did she care about women’s rights? To Mama, Soledad’s uncivilized behavior represented everything coarse and disgusting in a woman. She was deeply offended by the excitement that Soledad caused when she came to the house. Finally, sick from an epidemic and malnutrition and exhaustion, Soledad’s tiny body gave out. She died and, much to Mama’s anger, her son Alfonso became Mama’s irrevocable responsibility.

Mama did not see her sister-in-law as heroic, although Soledad had fought for ten years in the harsh terrain of Mexico, ill equipped and out manned, unpaid and driven only by the shredded dream of freedom. Mama only saw the additional burden of the child she would now have to raise with her own.

Daily, Mama expressed her frustration to Alfonso, berating his mother and her foolish choices. She called his mother a whore who lived like a gypsy, bedding any soldier who would tell her she was pretty. He was lucky, Mama would say, that his mother had died. Her jealousy of the romantic and heroic woman masked for all of Alfonso’s life the courage and spirit of the mother he never knew.

A few years later, one of Papa’s cousins, who already lived and worked in the US, insisted that we come right away to take part in the opportunities and wealth just north of the border. With the pressure of our growing family, including Alfonso, it seemed the right thing to do. So, Papa took Alfonso and came to Texas first to see if it was as fantastic as it was described. And it was, in every way. Six months later, Papa came for us.

As if on a splendid adventure, we crossed the border, dressed in all our finery. It was Washington’s Birthday, February 22, 1926. I remember entering the city of Laredo, Texas like I was walking in a dream. There were fireworks everywhere and flags and people celebrating in the streets, so beautiful and exciting. I was nearly five years old.

The family settled in San Antonio where Papa was working as a newspaper reporter and started a printing and bookbinding business. And, even after a problem with our documents caused us to be temporarily repatriated, we finally established roots in South Texas and Mama believed that her life of luxury was about to become even better. And it did . . . for almost three years.

Then, the Depression came and everything crashed overnight. The stock market and jobs, businesses - everything just crumbled. There was no time to plan or adjust- it seemed like the prosperous life everyone was enjoying burst like a water pipe and everyone’s dreams just gushed out into the street.

After that, things became very difficult for Mexican people. With no jobs for the men and many mouths to feed, my Mama was forced to work beneath her class in order to survive. She learned to raise chickens so the family could eat. She made liquor to sell during prohibition. She cooked for the parish priest or made garments for women who could afford new clothes. She became a maid, cleaning Anglo women’s homes. She gave birth to 13 children but only six survived. Through it all, Mama maintained an air of the life she once had, the elegance she still dreamed of.

Many years later, I found some research on the soldaderas. I started collecting it for Alfonso because I wanted him to know that he should be proud of his mother. I wanted to tell him that Soledad was fighting against discrimination and injustice. The soldaderas had helped the revolution stay alive. They were heroes. But he died before I could talk to him about it. I don’t think he ever knew.

Alfonso 1950 My mother, Gloria 1940

My mother went on to earn a college education, in spite of her Mama’s objection. She taught school for 33 years in Texas and taught her three daughters to be independent thinkers, self- sufficient and proud of our Mexican heritage. In only two generations, women of our family were transformed from both traditionalist women of leisure and zealous freedom fighters into penniless immigrants, and finally, into progressive American women of conviction and purpose.

I dream that there’s a little of Soledad in each of us. Whether she was a silly girl following the camps or a woman of grit who heard freedom’s call to arms, we will never know. I prefer to think that she was a little of both . . . dutiful to her cause and yet romantically in love with the idea that she would spill her blood to wash away injustice.1915 My Grandparents 1960

About The Author...

About The Author... Annette Leal MatternDuring her long career in technology, Annette held numerous corporate leadership positions with Fortune 100 companies where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. She published her first book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, to help others cope with the disease. She has also been published in Hispanic Engineer and several other media. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com/. She and her husband, Rich, live in Scottsdale AZ.

Annette Leal MatternDuring her long career in technology, Annette held numerous corporate leadership positions with Fortune 100 companies where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. She published her first book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, to help others cope with the disease. She has also been published in Hispanic Engineer and several other media. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com/. She and her husband, Rich, live in Scottsdale AZ.

era and a substantial reminder why one enjoys reading printed books in a cozy chair. Undeniably, portability is one advantage electronic devices have over the printed page. Whip out that iPhone while waiting for the bus and read to your heart’s content. Your heart. Me, I’m sure if I haul around this volume I either will forget my reading anteojos at home, or remember the lentes but set the book down somewhere and forget it. They say the memory’s the second thing to go and I do not remember the first.

era and a substantial reminder why one enjoys reading printed books in a cozy chair. Undeniably, portability is one advantage electronic devices have over the printed page. Whip out that iPhone while waiting for the bus and read to your heart’s content. Your heart. Me, I’m sure if I haul around this volume I either will forget my reading anteojos at home, or remember the lentes but set the book down somewhere and forget it. They say the memory’s the second thing to go and I do not remember the first.

Thank you for such a wonderful piece of family and Mexican history. I suggest that you share the link with Somos Primos at:

http://www.somosprimos.com/

These stories are so important for our people and others.

How family stories echo in literature. Elena Poniatowska has a soldadera whose story could mirror incidents in granma's and mama's history.

http://books.google.com/books?id=xGAGAAAACAAJ&dq=inauthor:%22+Elena+Poniatowska%22

Nice post - thanks for sharing your family stories. They are very similar to stories my mother still tells, and to the stories my grandmother used to tell.

Hola Annette,

Welcome to La Bloga. Thank you for your great family story.

saludos,

Rene

What a beautiful story. Although Alfonso wasn't able to read it, we have and therefore Soledad's story will live.

Thank you so much for sharing Soledad's life (and yours!) with us.

Thanks for such a warm welcome to La Bloga. I'm honored to add a small voice to the intelligent conversation of this site.

What an extraordinary story! Thank you for sharing this.