by Annette Leal Mattern

Spanish rule of New Spain brought with it a strict cast system carried over from the Spanish Reconquista, an efficient method of distinguishing pure old-blood Christians from converted Muslims or Jews. In Latin America, this distinction held Peninsulares, Spaniards born on the Iberian Peninsula, at the top of the social order. It was they who were appointed by the crown to the highest ecclesiastic, political and military positions. The next rank among the citizenry was the Criollo, pure blooded Spaniards born in the Americas, who were mostly elite land owners. Next in line were the "Mestizos," half Spanish and half Amerindian, assigned as local administrators and managers of the indigenous people. Finally, the lower classes comprised of mulatos (mixed African and European or Indian), Indios, and blacks - destined to live their lives as laborers, peasants and slaves.

The following is a story. A fairytale set against a horizon in history.

The Indian bowed his head before the

alcalde awaiting permission to speak. The day was scorching even for September, the kind of day when sweat stood on every living, breathing being. He stood for most of the afternoon in that same position, focused on a small spider hard at work releasing its prey from a strategically placed web, a distraction that helped him forget the pain in his legs from standing after the five days’ walk to arrive at the provincial government headquarters. His wife had died in childbirth and he was here to request permission to bury her on ancestral burial grounds. But he has no voice here and must wait…and wait…until it suits the administrator to review his case.

The staff officers in the room show their incredible disdain for the Indian, not because he is different but because he is too much alike.

The

alcalde, a Mestizo educated in Seville, despised the Indians and the notion that their blood ran in his veins. His authority and superiority were a constant denial of his mixed bloodline, his ambition fueled by the perception that Indians were born lazy and stupid and were therefore destined to be slaves.

Now that he finished the other matters of state, he allowed the Indian permission to speak, if for no other reason, to remove the smell from his office.

“Please sir,” the Indian spoke in crude Spanish, “here is the government paper. It shows the rights of our people. I ask only to bury my wife there.”

The

alcalde looked at the dark-skinned slave with disdain. This poor fool had no rights, save those Mother Spain bestowed upon him in her generosity. They were so like children.

“I’ll decide what that paper says, you ignorant worm. You can’t even write you name! How dare you tell me what an official government letter says.” He sneered as he grabbed the worn, dirty document.

“But, I can read,

Excilencio. I learn in the mission.”

The

alcalde reviewed the document, all the while thinking what a mistake it was to educate the peasants. He would speak to the Bishop about this at dinner.

The document was a form of treaty, dated one hundred years earlier, as part of a settlement of an uprising, involving ancient, historical and religious sites confiscated by the Spanish. It ceded property near Guadalajara to the family for religious purposes.

“I do not see why you would travel all that distance with a dead body, anyway.” He laughed and he turned to his staff to join in the ridicule of the Indian.

“Can you believe the Army is worried about a revolt from these stupid fools? They need a good beating just to keep them awake.” More laughter.

“Well, peasant, you will need a letter of permission to inter your dead wife- oh, and any litter she might have dropped at the time. As this is a very old claim, it may take some time to verify. You do know this land is practically worthless, don’t you. There have been no new strikes in those mountains in years.” Like a cat tormenting a wounded sparrow, he toyed with the Indian who was now drenched in sweat.

“The government controls all mining activities anyway, you see. Therefore, we could dispense with the investigation if you will simply transfer the mining rights to us straight away. In this situation, I can simply grant you immediate permission to get that body in the ground before it falls apart or is eaten by maggots. Go ahead, sign. Let’s see if you can, indeed write your name, Indian.”

On the matter of burying his beloved wife, he cared very little what vile words they used to speak of her. They were vermin and soon would be dead. Moreover, this was the worst of the lot, the Mestizos, children of mixed parentage, always Spanish fathers and Indian mothers. Their impure blood so repelled Spanish society that most returned to Mexico after being educated in Europe. Here, they became the dogs of the ruling class, the tyrants of their half brothers.

“I will sign,

Excilencio. I must take my wife. All the women of her line must be buried there.”

And with that, he was gone. Finally.

The territorial official swaggered home that evening and added the new registration to the safe in his mahogany lined library of his sprawling hacienda, a splendid residence styled in all things perfectly European. He congratulated himself on his scheme to build an estate for his retirement far away from this wretched place, his plan to return to Europe a wealthy man. No one would laugh at him then as they had when he was in school. Southern Spain had every kind of blood in the modern world, especially Andalucía where questions of heritage were seldom asked. And, with enough money, one could always enhance one’s bloodline records.

In preparation for his eventual escape, he had countless mining rights assigned to him personally; not to the state as was his duty, but to himself, the man who would soon leave with his beautiful, fair-skinned wife. It mattered not at all that he was exploiting the Indians for they were hardly more than animals. They were merely a conveniently embedded labor force, unlike other territories that had need of African slaves. Fortunately, these Indians were all that was necessary to feed Europe’s voracious appetite for Mexico’s rich natural resources.

As

alcalde, he governed the entire district of south-central Mexico from his comfortable office in Guadalajara. Even though he loathed the country and its ignorant natives, he knew that he was sitting atop gold and silver veins that generated infinite wealth. The question was when to leave…when was it enough to live a comfortable, elegant life in Europe?

The year is 1810. In France, Napoleon has his marriage to Josephine annulled so that he can marry Marie-Louise of Austria while France continues its acquisition of European territories from Holland to Seville. In the United Kingdom, King George III, widely rumored to be mad, is formally recognized as insane. Meanwhile, 4,000 American sailors have been captured by the British, halting trade between the US and England and building up tension that will erupt into the war of 1812.

In the United States, John Jacob Astor launches the Pacific Fur Company in Oregon, creating a trading ring between New York, the Oregon territory, Russian Alaska and China. Meanwhile, the Republic of West Florida declares freedom from Spain and is annexed into the United States.

Spain is besieged by colonial uprisings throughout Central and South America. West Florida, Columbia, Argentina and Chile gain independence. Tension spreads like an epidemic across the colonies, ideas of freedom and revolution - no longer whispered - become louder and louder.

Undaunted by the rumblings, the

alcalde is nestled in his home in Guadalajara, humored by the

latest boon to his personal treasure. Life is good and he can tolerate a little more inconvenience before he leaves Mexico forever. It is the night of September 15, 1810.

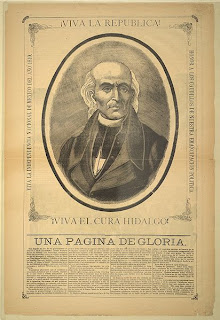

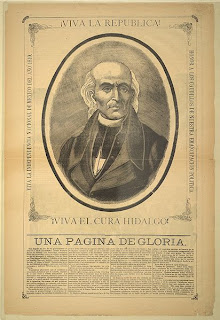

Coincidentally, in neighboring Guanajuato, a major colonial mining center, a revolt takes place that night under the leadership of an unlikely hero. A

criollo priest, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, declares war against the colonial government in a call to arms that becomes known as

El Grito de Dolores, the cry for independence.

The next day, September 16, throngs of peasants join forces to eliminate the oppression of the lower class. So impassioned are the revolutionaries that they barricade the leading citizens in a warehouse and set fire to the building, massacring most of the town’s elite, followed by a bloody decade of war. The Mexican War for Independence had begun and in an instant, a cast system that so clearly defined the value of a man was drowned in a sea of justice.

Father Hidalgo and Historic Guanajuato

__________________

About the author: Annette Leal Mattern held numerous corporate leadership positions where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. Her book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, helps people cope with the disease. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com.

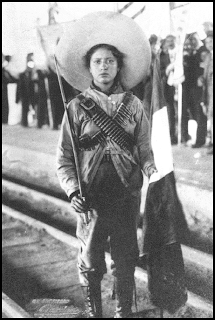

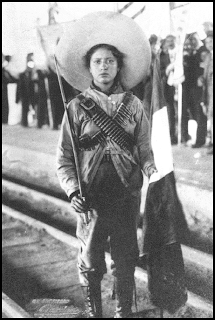

Unknown Soldaderas - Mexican Revolution

Porfirio Dias was Mexico’s president for 30 years following centuries of occupation, colonization, uprisings, invasions by Spain and France, and war with the United States. Dias’ autocratic regime gave rise to a new, industrialized Mexico, made possible by exploiting the majority of the people, stripping them of human rights while Dias built political power and personal wealth. Those who suffered most were the poor, the laborers, indios and women. In 1895, civil code was passed which severely restricted Mexican women to a life of serving their husbands, their families, and the Catholic Church.

The country was divided on these and other issues and Mexico fell into a ten-year period of chaos, with back-to-back political coups and foreign intervention. But, through the shifts in power, peasants gathered together to create a land that could serve all of Mexico’s people, including her women.This presented a conflict between traditional women who enjoyed their more domestic, subservient roles and an emerging feminism completely unknown in Mexico before. It became one of the underlying principles of the Mexican Revolution and the subject of one of the great reforms to arise from this period.

The women who stood up for higher ideals and demanded change were extraordinary, particularly given their social position and their time in history. They joined the Revolution, demanding reform across a country in disarray. Some became political voices, journalists who wrote articles opposing the tyranny of the ruling class. Some became nurses treating wounded revolutionary soldiers. Others served as spies or procured provisions for the small bands of peasants who continued fighting for freedom from 1910 until well after 1920. A few picked up weapons and joined forces, with Zapata in the south or Villa in the north, to fight along side the men. They became known as las soldaderas.

My mother, now in her late eighties, recalled the stories from her childhood in Mexico of a mysterious woman her Mama hated, a woman who came to their house to see the son she had left behind. Her name was Soledad.

For years, Soledad was described by my grandmother as a reckless harlot who irresponsibly left her child in the care of others so she could follow the revolutionary soldiers. To my grandmother, who could only view the events through the lens of her traditional upbringing, it was disgraceful. And, for more than a lifetime, only one side of the story was told. Finally, decades later, when my mother researched Mexican history, another story, long forgotten, materialized. This is my mother, Gloria's, recollection.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was born in 1921 but I can remember from about the age of 4, our life in Mexico. Papa’s name was Juan. He was born in Linares, Mexico, located about 130 km from Monterrey City in the State of Nuevo Leon.

Juan

JuanHe was orphaned in early childhood and sent to the seminary where he got an education. He was a newspaper reporter, book binder and writer. He was also an amateur ‘novillero,’ a novice bullfighter who fights young bulls. He had a younger sister, Soledad.

My parents settled in Monterrey once they were married. Mama was quite young, about 13. In the early years of the marriage, Mama – still a child herself, loved dressing up in beautiful clothes - taffeta dresses in popular styles of the time, fur coats and gold jewelry. She wore them on Sunday outings. Papa was very active in social clubs, sports and celebrations around town. Mama, beautiful and proud, saw her life as sophisticated and special, the life she was born to live.

We had 2 maids- one to care for us children, the other to cook and clean. Our house was always spotless and it seemed very grand. There was a pond with fine little pebbles inside the house, and here I could play for hours as a child. In the back yard was a beautiful garden. We seldom interacted with Mama but rather with my Nana, because proper women of class did not bother with domestic chores. When I was bathed by my Nana, dried with clean sheets, dressed in a hand- embroidered slip, I felt like a princess.

Gloria, age 4

Gloria, age 4

The few memories of going out with Mama were of going to the tailor for new clothes of fine materials, fur trim, and adornments. Mama always wore jewels and lace and very delicate clothing. We children always had to be dressed up as well. We were like her little dolls.

The biggest problem in Mama’s life was her sister-in-law, Soledad. At the age of about 17, Soledad had become a ‘Villista,’ one of the volunteers supporting Pancho Villa in the Revolution. This was a great embarrassment to Mama. To make matters worse, Soledad fell in love with a French soldier and bore their son, Alfonso. But, instead of coming home and managing her responsibilities, Soledad continued fighting the war. Alfonso lived with us.

Between battles, Soledad nursed the wounded or went begging for food and supplies, not seeing her son for months. They say that that she would sneak to our house at night, all filthy and hungry, and want to see Alfonso. She didn’t bring money or food, and even asked for provisions to take back with her. Mama hated her for this.

Mama was not political. She enjoyed her role, surrounded by domestic affluence and security. What did she care about women’s rights? To Mama, Soledad’s uncivilized behavior represented everything coarse and disgusting in a woman. She was deeply offended by the excitement that Soledad caused when she came to the house. Finally, sick from an epidemic and malnutrition and exhaustion, Soledad’s tiny body gave out. She died and, much to Mama’s anger, her son Alfonso became Mama’s irrevocable responsibility.

Mama did not see her sister-in-law as heroic, although Soledad had fought for ten years in the harsh terrain of Mexico, ill equipped and out manned, unpaid and driven only by the shredded dream of freedom. Mama only saw the additional burden of the child she would now have to raise with her own.

Daily, Mama expressed her frustration to Alfonso, berating his mother and her foolish choices. She called his mother a whore who lived like a gypsy, bedding any soldier who would tell her she was pretty. He was lucky, Mama would say, that his mother had died. Her jealousy of the romantic and heroic woman masked for all of Alfonso’s life the courage and spirit of the mother he never knew.

A few years later, one of Papa’s cousins, who already lived and worked in the US, insisted that we come right away to take part in the opportunities and wealth just north of the border. With the pressure of our growing family, including Alfonso, it seemed the right thing to do. So, Papa took Alfonso and came to Texas first to see if it was as fantastic as it was described. And it was, in every way. Six months later, Papa came for us.

As if on a splendid adventure, we crossed the border, dressed in all our finery. It was Washington’s Birthday, February 22, 1926. I remember entering the city of Laredo, Texas like I was walking in a dream. There were fireworks everywhere and flags and people celebrating in the streets, so beautiful and exciting. I was nearly five years old.

The family settled in San Antonio where Papa was working as a newspaper reporter and started a printing and bookbinding business. And, even after a problem with our documents caused us to be temporarily repatriated, we finally established roots in South Texas and Mama believed that her life of luxury was about to become even better. And it did . . . for almost three years.

Then, the Depression came and everything crashed overnight. The stock market and jobs, businesses - everything just crumbled. There was no time to plan or adjust- it seemed like the prosperous life everyone was enjoying burst like a water pipe and everyone’s dreams just gushed out into the street.

After that, things became very difficult for Mexican people. With no jobs for the men and many mouths to feed, my Mama was forced to work beneath her class in order to survive. She learned to raise chickens so the family could eat. She made liquor to sell during prohibition. She cooked for the parish priest or made garments for women who could afford new clothes. She became a maid, cleaning Anglo women’s homes. She gave birth to 13 children but only six survived. Through it all, Mama maintained an air of the life she once had, the elegance she still dreamed of.

Many years later, I found some research on the soldaderas. I started collecting it for Alfonso because I wanted him to know that he should be proud of his mother. I wanted to tell him that Soledad was fighting against discrimination and injustice. The soldaderas had helped the revolution stay alive. They were heroes. But he died before I could talk to him about it. I don’t think he ever knew.

Alfonso 1950 My mother, Gloria 1940

My mother went on to earn a college education, in spite of her Mama’s objection. She taught school for 33 years in Texas and taught her three daughters to be independent thinkers, self- sufficient and proud of our Mexican heritage. In only two generations, women of our family were transformed from both traditionalist women of leisure and zealous freedom fighters into penniless immigrants, and finally, into progressive American women of conviction and purpose.

I dream that there’s a little of Soledad in each of us. Whether she was a silly girl following the camps or a woman of grit who heard freedom’s call to arms, we will never know. I prefer to think that she was a little of both . . . dutiful to her cause and yet romantically in love with the idea that she would spill her blood to wash away injustice.1915 My Grandparents 1960

About The Author...

About The Author... Annette Leal MatternDuring her long career in technology, Annette held numerous corporate leadership positions with Fortune 100 companies where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. She published her first book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, to help others cope with the disease. She has also been published in Hispanic Engineer and several other media. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com/. She and her husband, Rich, live in Scottsdale AZ.

Annette Leal MatternDuring her long career in technology, Annette held numerous corporate leadership positions with Fortune 100 companies where she championed development of minorities for upper management. She received the National Women of Color Technology Award for Enlightenment for her diversity achievements and was recognized by Latina Style and Vice President Gore as one of the most influential Latinas in American business. In 2000, she left her corporate work to devote herself to women's cancer causes. She published her first book, Outside The Lines of love, life, and cancer, to help others cope with the disease. She has also been published in Hispanic Engineer and several other media. Annette serves on the board of directors of the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance and founded the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Arizona, for which she serves as president. Annette also writes for http://www.empowher.com/. She and her husband, Rich, live in Scottsdale AZ.

Thank you for such a wonderful piece of family and Mexican history. I suggest that you share the link with Somos Primos at:

http://www.somosprimos.com/

These stories are so important for our people and others.

How family stories echo in literature. Elena Poniatowska has a soldadera whose story could mirror incidents in granma's and mama's history.

http://books.google.com/books?id=xGAGAAAACAAJ&dq=inauthor:%22+Elena+Poniatowska%22

Nice post - thanks for sharing your family stories. They are very similar to stories my mother still tells, and to the stories my grandmother used to tell.

Hola Annette,

Welcome to La Bloga. Thank you for your great family story.

saludos,

Rene

What a beautiful story. Although Alfonso wasn't able to read it, we have and therefore Soledad's story will live.

Thank you so much for sharing Soledad's life (and yours!) with us.

Thanks for such a warm welcome to La Bloga. I'm honored to add a small voice to the intelligent conversation of this site.

What an extraordinary story! Thank you for sharing this.