By David J. Peterson

My name is David Peterson, and I’m a conlanger. “What’s a conlanger,” you may ask? Thanks to the recent addition of the word “conlang” to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), I can now say, “Look it up!” But to save you the trouble, a conlanger is a constructed language (or conlang) maker — i.e. one who creates languages.

Language creation has been around since at least the 12th century, when the German abbess Hildegard von Bingen created her Lingua Ignota — Latin for “hidden language” — an invented vocabulary she used for writing hymns. In the centuries that followed, philosophers like Leibniz and John Wilkins would create languages that were intended to serve as grand classification systems, and idealists like L. L. Zamenhof would create languages intended to simplify international communication. All these systems focused on the basic utility of language — its ability to encode and convey meaning. That would change in the 20th century.

Tolkien: the father of modern conlanging

Before crafting the tales of Middle-Earth, J. R. R. Tolkien was a conlanger. Unlike the many known to history who came before him, though, Tolkien created languages for the pure joy of it. Professionally, he became a philologist, but he continued to work on his own languages, eventually creating his famous Lord of the Rings series as an extension of the linguistic legendarium he’d been crafting for many years. Though his written works would become more famous than his linguistic creations, his conlangs, in particular Sindarin and Quenya, would go on to inspire new generations of conlangers throughout the rest of the 20th century.

Due to the general obscurity of the practice, many conlangers remained unknown to each other until the early 1990s, when home internet use started to become more and more common. The first dedicated meeting place for conlangers, virtual or otherwise, was the Conlang Listserv (an online mailing list). Some list members came out of interest in Tolkien’s languages, as well as other large projects, like Esperanto or Lojban, but the majority came to discuss their own work, and to meet and learn from others who also created languages.

Since the founding of the original Conlang Listserv, many other meeting places have sprung up online, and through a couple of decades of regular conlanger interaction, the practice of conlanging has evolved.

Conlang typology

Conlangs have been separated into different types since at least the 19th century. First came the philosophical languages, as discussed, then the auxiliary languages like Esperanto (also known as auxlangs), but with Tolkien emerged a new type of language: the artistic language, or artlang. At its most basic, an artlang is a conlang created for artistic purposes, but that broad definition includes many wildly divergent languages (compare Denis Moskowitz’s Rikchik to Sylvia Sotomayor’s Kēlen). Finer-grained distinctions became necessary as the community grew, and so emerged the naturalistic conlang.

This is where the languages of HBO’s Game of Thrones and Syfy’s Defiance come in. The languages I’ve created for the shows I work on come out of the naturalist tradition. The goal with a naturalistic conlang is to create a language that’s as realistic as possible. The realism of a language is grounded in the reality (fictional or otherwise) of its speakers. If the speakers are more or less human (or humanoid) and are intended to be portrayed in a realistic fashion, then their language should be as similar as possible to a natural language (i.e. a language that exists here on Earth, like Spanish, Tagalog, or Cham).

The natural languages we speak are large, but also redundant and imperfect in a uniquely human way. Conlangers have gotten pretty good at emulating them over the years, usually employing one of two different approaches. The first, which I call the façade method, is to create a language that looks like a modern natural language by replicating the various features of a modern natural language. Thus, if English has irregular plurals, such as mouse~mice, then the conlang will have irregular plurals, too, by targeting certain nouns and making their plurals irregular in some way.

The historical method: making sense of irregular plurals in Valyrian

A contrasting approach is the method that Tolkien pioneered called the historical method. With the historical method, an ancestor language called a proto-language is created, and the desired language is evolved from it, via simulated linguistic evolution. The process takes a lot longer, but in some ways it’s simpler, since irregularities will naturally emerge, rather than having to be created by hand. For example, in Game of Thrones, the High Valyrian language Daenerys speaks differs from the Low Valyrian the residents of Slaver’s Bay speak. In fact, the latter evolved from the former. As the language evolved, it produced some natural irregularities. Consider the following nouns and their plurals from the Valyrian spoken in Slaver’s Bay:

A contrasting approach is the method that Tolkien pioneered called the historical method. With the historical method, an ancestor language called a proto-language is created, and the desired language is evolved from it, via simulated linguistic evolution. The process takes a lot longer, but in some ways it’s simpler, since irregularities will naturally emerge, rather than having to be created by hand. For example, in Game of Thrones, the High Valyrian language Daenerys speaks differs from the Low Valyrian the residents of Slaver’s Bay speak. In fact, the latter evolved from the former. As the language evolved, it produced some natural irregularities. Consider the following nouns and their plurals from the Valyrian spoken in Slaver’s Bay:

hubre “goat” hubres “goats”

dare “queen” dari “queens”

aeske “master” aeske “masters”

Given that the singular forms all end in ‘e’, one has to say at least two of the plurals presented are irregular. But why the arbitrary differences in the plural forms? It turns out it’s because the three nouns with identical singular terminations used to have very different forms in the older language, High Valyrian, as shown below:

hobres “goat” hobresse “goats”

dāria “queen” dārī “queens”

āeksio “master” āeksia “masters”

Each of these alternations is quite regular in High Valyrian. In the simulated history, a series of sound changes which simplified the ends of words produced identical terminations for each of the three words in the singular, leaving later speakers having to memorize which have irregular plurals and which regular.

Conceptualizing time

Simulated evolution applies to both grammar and the lexicon, as well. For example, natural languages often derive terminology for abstract concepts metaphorically from terminology for concrete concepts. Time, for instance, is an abstract concept that is frequently discussed using spatial terminology. How it’s done differs from language to language. In English, events that occur later in time occur after the present (where “after” derives from “aft,” a word meaning “behind”), and events that occur earlier in time occur before the present. Thus, time is conceptualized as a being standing in the present, facing the past, with the future behind them.

In Irathient, a language I created for Syfy’s Defiance, time is conceptualized vertically, rather than horizontally. The word for “after”, in temporal terms, is shei, which derives from a word meaning “above”; “before”, on the other hand, is ur, which also means “below” or “underneath”. The general metaphor that the future is up and the past is down bears out throughout the rest of the language, where if one wanted to say “Go back to what you were saying before”, the literal Irathient translation would be “Go down to what you were saying underneath”.

Ultimately, what one hears on screen sounds and feels like a natural language, regardless of whether or not one knows the work that went on behind the scenes. Since the prop used on screen is a language, though, rather than a costume or a piece of the set, the words can be recorded and analyzed at any time. Consequently, a conlang needs to be real in a way that a throne or a 700 foot wall of ice does not.

It’s still extraordinary to me that in less than 25 years, we came from a time when many conlangers were not aware that there were other conlangers to a time where our work is able to add to the authenticity of some of the best productions the big and small screen have to offer. The addition of the word “conlang” to the OED is a fitting capper to an unbelievable quarter century.

David J. Peterson is a language creator who works on HBO’s Game of Thrones, Syfy’s Defiance, and Syfy’s Dominion. You can find him on Twitter at @Dedalvs or on Tumblr.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: Game of Thrones Season 3 – Dragon Shadow Wallpaper and Game of Thrones Season 3 - Daenerys Wallpaper. ©2014 Home Box Office, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

The post How I created the languages of Dothraki and Valyrian for Game of Thrones appeared first on OUPblog.

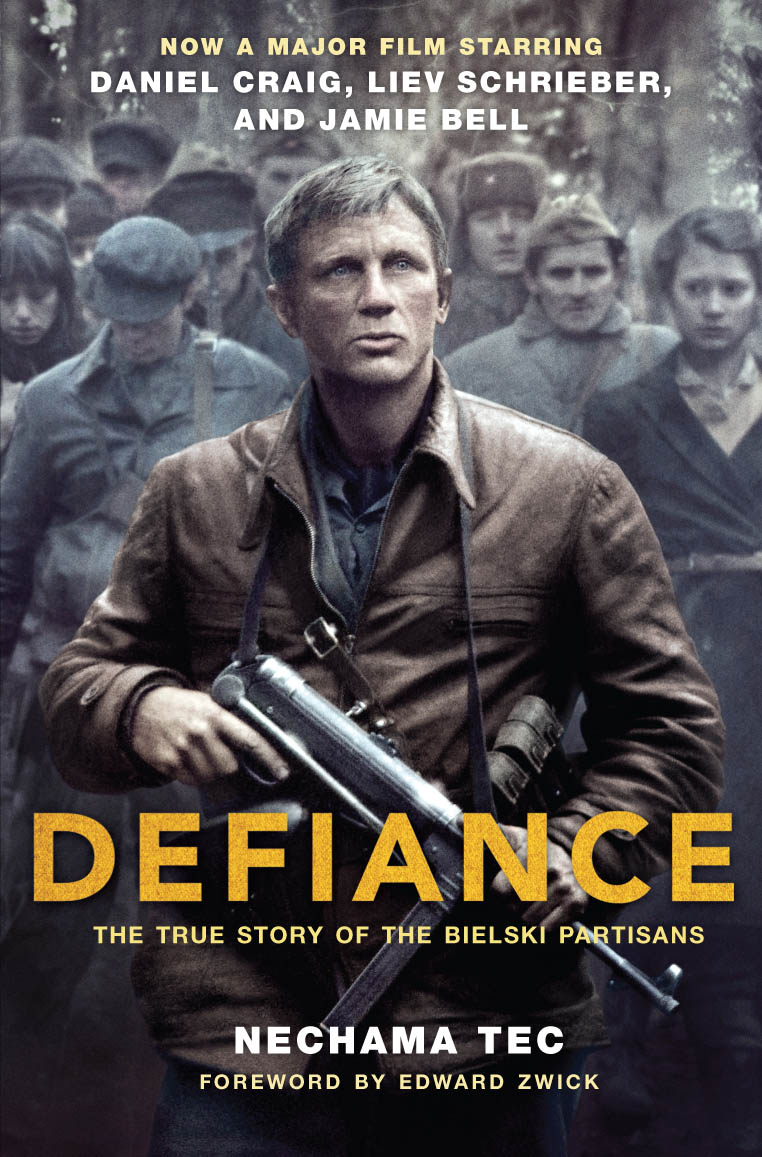

Their joint military ventures began in the last quarter of 1942 and continued into the second half of 1943. Although such anti-German moves were initiated by Panchenko, the two otriads each carried the same burden. Publicly Tuvia continued to emphasize his personal commitment to anti-German activities. In reality he and his group were under pressure to participate. A refusal could have endangered the very existence of the Bielski otriad. Russian partisans would not have tolerated an unwillingness to fight, especially not from Jews whom they suspected of cowardice. At this early stage, all forest dwellers were united in their hatred toward the Germans and their collaborators. These feelings of hostility were supported by equally strong ideas that it was important to fight their common enemy, the Germans.

Their joint military ventures began in the last quarter of 1942 and continued into the second half of 1943. Although such anti-German moves were initiated by Panchenko, the two otriads each carried the same burden. Publicly Tuvia continued to emphasize his personal commitment to anti-German activities. In reality he and his group were under pressure to participate. A refusal could have endangered the very existence of the Bielski otriad. Russian partisans would not have tolerated an unwillingness to fight, especially not from Jews whom they suspected of cowardice. At this early stage, all forest dwellers were united in their hatred toward the Germans and their collaborators. These feelings of hostility were supported by equally strong ideas that it was important to fight their common enemy, the Germans. Author: Margaret Shannon

Author: Margaret Shannon

Wanted to express my admiration!!! I’ve heard of this film long ago and finally managed to watch it (have found it at http://rapidpedia.com/?q=Defiance+). I am sure such films should be included into the school plan!