new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: funny books, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: funny books in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 10/13/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Sociology,

publishing,

Education,

Technology,

digital,

kindle,

Barack Obama,

print,

ebook,

baron,

Linguistics,

ereader,

iPad,

*Featured,

Arts & Humanities,

Naomi S. Baron,

Words Onscreen,

Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World,

Add a tag

Mark Twain is reputed to have quipped, “Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated.” Such hyperbole aptly applies to predictions that digital reading will soon triumph over print.

In late 2012, Ben Horowitz (co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz Venture Capital) declared, “Babies born today will probably never read anything in print.” Now four years on, the plausibility of his forecast has already faded.

The post Will print die?: When the inevitable isn’t appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

Mark,

baron,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

concise,

spelling bee,

gleanings,

*Featured,

spelling reform,

slough,

myrk,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Baron, mark, and concise.

I am always glad to hear from our readers. This time I noted with pleasure that both comments on baron (see them posted where they belong) were not new to me. I followed all the references in Franz Settegast’s later article (they are not yet to be found in such abundance in my bibliography of English etymology) and those in later sources and dictionaries, and, quite naturally, the quotation from Isidore and the formula in which baron means “husband” figure prominently in every serious work on the subject. No one objected to the hypothesis I attempted to revive. Regrettably, Romance etymologists hardly ever read this blog. In any case, I have not heard their opinion about bigot, beggar, bugger, and now baron. On the other hand, when I say something suspicious or wrong, such statements arouse immediate protest, so perhaps my voice is not lost in the wilderness.

Thus, in one of the letters sent to Oxford University Press I was told that my criticism of the phrase short and concise “is not well taken,” because legal English does make use of this tautological binomial, along with many more like it, in which two synonyms—one English and one French—coexist and reinforce each other. What our correspondent said is, no doubt, correct, and I am aware of numerous Middle English legal compounds of the love-amour type. However, I am afraid that some people who have as little knowledge of legalese as I do misuse concise and have a notion that this adjective is a synonym of precise. Perhaps someone can give us more information on this point. I also want to thank our correspondent who took issue with my statement on the pronunciation of shire: my rule was too rigid.

As for mark, our old correspondent Nikita (he never gives his last name) is certainly right. Ukraine (that is, Ukraina) means “borderland.” In the past, the word was not a place name, and other borderlands were also called this. Equally relevant are the examples Mr. Cowan cited. I don’t know whether Tolkien punned on myrk-, but Old Icelandic myrk- does mean murk ~ murky, as in Myrk-við “Dark Forest” (so a kind of Schwarzwald) and Myrk-á “Dark River.”

Spelling and general intercourse.

I suspect that Mr. Bett (see his comments on the previous gleanings) is an advocate of an all-or-nothing reform. I’d be happy to see English spelling revolutionized, and my suggestion (step by step) is based on expedience (politics) rather than any scholarly considerations. When people speak of phonetic spelling, they usually mean phonemic spelling, so this is not an issue. But I would like to remind everyone that the English Spelling Society was formed in 1908. And what progress has it made in 116 years? Compare the two texts given below.

To begin with, I’ll quote a few passages from Professor Gilbert Murray’s article published in The Spectator 157, 1936, pp. 983-984. At that time, he was the President of the Simplified Spelling Society.

“There are two plain reasons for the reform of English spelling. In education the work of learning to read and write his own tongue is said to cost the English child [I apologize for Murray’s possessive pronoun] a year longer than, for example, the Italian child, and certainly tends to confuse his mind. For purposes of commerce and general intercourse, where the world badly needs a universal auxiliary language and English is already beginning in many parts of the world to serve this purpose, the enormous difficulty and irrationality of English spelling is holding the process back.…”

He continued:

“Now nearly all languages have a periodic ‘spring cleaning’ of their orthography. English had a tremendous ‘spring cleaning’ between the twelfth and the fourteenth century.… It is practically Dryden’s spelling that we now use, but few can doubt that the time for another ‘spring cleaning’ is fully arrived… It must not be supposed that the reformers want an exact phonetic alphabet…. What we need is merely a standard spelling for a standard language…. The ‘spring cleaning’ which my society asks for is, I think, quite certain to come; though the longer it is delayed the more revolutionary is will be. It may come, as Lord Bryce, when President of the British Academy, desired, by means of a Royal Commission or a special committee of the Academy. It may, on the other hand, come through the overpowering need of nations in the Far East, and perhaps in the North of Europe, to have an auxiliary language, easy to learn, widely spoken, commercially convenient, and with a great literature behind it, in a form intelligible to write and to speak.”

All this could be written today, even though with a few additions and corrections. English is no longer beginning to serve the purpose of an international language; it has played this role since World War II. We no longer believe that the desired “cleaning” is sure to come: we can only hope for the best.

Let us now listen to Mr. Stephen Linstead, the present Chair of the English Spelling Society, who said to The Daily Telegraph on 23 May 2014 the following: “The spelling of roughly 35 percent of the commonest English words is, to a degree, irregular or ambiguous; meaning that the learner has to memorise these words.” A need to memorize irregularity, he explains, “costs children precious learning time, and us—as a nation—money…. A study carried out in 2001 revealed that English speaking children can take over two years longer to learn basic words compared with children in other countries where the spelling system is more regular.”

We can see that our educational system is making great strides: what used to take one year now takes two. Mr. Linstead says other things worth hearing of which I’ll single out the proposal. It concerns the formation of an international English Spelling Congress “made up of English speakers from across the world who are open to the possibility of improving English spelling and who would like to contribute to the difficulty of mastering our spelling system.” As I understand it, the reformers plan to pay special attention to organizational matters, rather than arguing about the details of English spelling. This looks like a rational attitude. The public is not interested in the reform. Nor did it show any enthusiasm for it in 1936. There were two letters to the editor in response to Professor Gilbert’s article, but both came from the members of the Society, that is, from the “choir.” If the Congress materializes, it should include a lot of very influential people (what about Lord Bryce’s idea?). Otherwise, we will keep talking for another one hundred and six years without any results.

Busy as a bee.

The public, as I said above, does not care about the reform, but it is greedy, covets monetary prizes, and sends children to a torture known as spelling bee. The hive originated in 1925. Here is a case of a bright thirteen year old boy. He speaks English (and to some extent two other languages, one of them learned at home) and is an avid reader. He made it to the semifinals but misspelled ananke (a useful word that reminds even the gods that doom is unavoidable—just what a young boy should keep in mind). I don’t know what he did wrong. Probably he assumed that the word was Latin and spelled it with a c, but alas and alack, it is Greek. For eight weeks a coach (another young student) used to work with the boy three times a week. What a waste! The boy said: “I was really nervous, because you really don’t know what word you were going to get. I wanted to make it farther. [However,] I was really pleased with how I did and how I placed.” I am afraid he will grow up knowing several hundred words he will never see in books and using really three times in two lines. Remembering the spelling of ananke will be the only reward for his efforts.

A snake in the slough of despond. Image credit: A Cantil (Agkistrodon bilineatus) with a shed skin nearby at Little Ray’s Reptile Zoo. Photo by Jonathan Crowe. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via mcwetboy Flickr.

I think society (society at large, not the Spelling Society) should do what administrators, masters of a meaningless jargon, call sorting out priorities, stop abusing children, forget the fate of the gods, and concentrate on the misery of the mortals who try to make sense of bough, cough, dough, rough, through, and the horrors of the word slough.

To be continued next week.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for June 2014, part one appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/18/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

baron,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Germanic,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Classical Latin,

baro,

Franz Settegast,

George G. Nicholson,

Harri Meyer,

Pierre Guirot,

Waronem,

Books,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

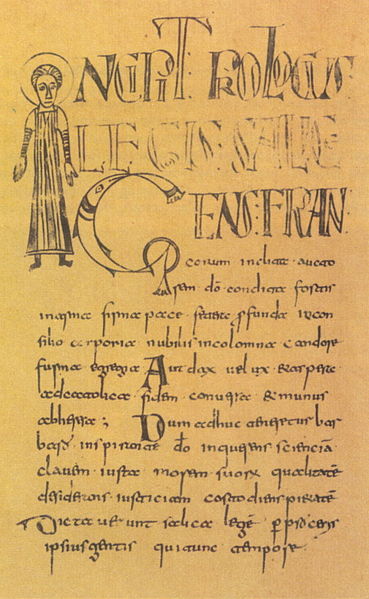

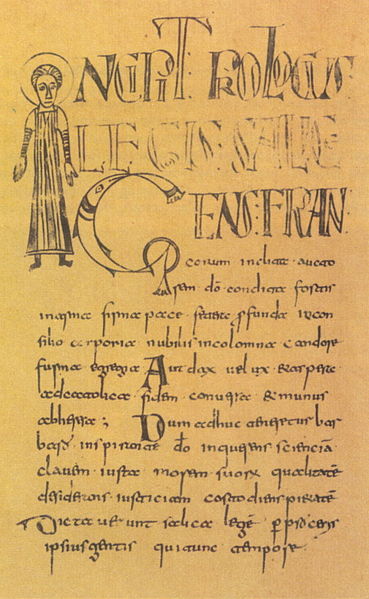

I will begin with a short summary of the previous post. In English texts, the noun baron surfaced in 1200, which means that it became current not much earlier than the end of the twelfth century. It has been traced to Semitic (a fanciful derivation), Celtic, Latin (a variety of proposals), and Germanic. The Old English words beorn “man; fighter, warrior” and bearn “child; bairn” are unlikely sources of baron. Latin vir “man; husband” would not have become baron for phonetic reasons. The same holds for some other proposed Latin v-words. However, in Latin, baro1 “fool; simpleton” and baro2 “a free man” have been attested. As the putative etymons of baron both pose problems. Baro1 meant “fool” and “a strong, muscular man; a man lacking polish, someone from a province,” while baro1 emerged only in the Frankish law code (Lex Salica) known from early medieval manuscripts. The laws, even though they codified the life of a Germanic tribe, were written in Latin, so that there is no certainty that baro2 is a genuine Latin noun: it could be a Latinized Germanic legal term the scribes preferred to leave untranslated. It is hard to decide whether in dealing with Latin baro1 we have two different words (“fool” and “a strong, unpolished man”) or two meanings of the same word. If the second treatment of baro is to be preferred, then what was the way of development: from “fool” to “a strong man” or from “a strong man” to “fool”? The German linguist Franz Settegast believed that only the second alternative should be considered and derived baron from baro1, but he said nothing definite on the history of its Germanic homonym. In his opinion, baro of Lex Salica might be a different word. This is approximately where I left off last week.

As regards the fortunes of Classical Latin baro, Settegast’s idea is reasonable. He believed that, although thanks to Cicero “fool” is the best-remembered sense of baro, it is not the original one. More probably, he suggested, the word arose with the meaning “a strong man” and later acquired the negative connotations “hillbilly, rough person,” as opposed to someone who learned good manners in the capital, was urbane, and depended on his intellect rather than physical strength. Some analogs Settegast cited missed the point, but for his main argument one can find ample confirmation. Thus, in animal folklore, brawn never goes together with brain. The trickster of animal tales is usually a smart weakling: the cat, the coyote, Brer Rabbit, and the rest. Even the fox, though certainly not a puny creature, is smaller and weaker than the wolf and the bear. The trickster’s dupes are the wolf and the bear.

The Gipsy baron of Johann Strauss

As usual in such cases, Settegast had to depend on one or more missing links. He assumed that baro developed in two ways: in one direction it allegedly went from “a strong man” to “fool” and in the other to “*fighter, *warrior, *man” and further to “baron.” The senses I marked with asterisks have not been recorded. Yet many influential specialists in the history of Latin and the Romance languages accepted Settegast’s reconstruction. Despite the consensus the pendulum soon swung in the opposite direction, and etymologists returned to the idea that baron could not be related to a word meaning “fool; simpleton” and traced it to Old High German baro, as we know it from Lex Salica. To support this derivation, one had to offer a plausible etymology of German baro, and Settegast’s opponents came up with the following. There is an Old Icelandic verb berja “to strike,” a cognate of Latin ferio “to strike; kill”; its reflexive form berja-sk means “to fight” (that is, “to exchange blows”). Old High German baro emerged in this scheme as “fighter,” an ideal semantic etymon of baron. However, Icelandic did not have the noun bero “fighter.” Only Old High German bero is known, but it is related to the verb beran “bear; carry” and means “carrier, porter.” It has nothing to do with Icelandic berja ~ berjask. Baro “fighter” ended up with the single support of the nonexistent noun bero “fighter” and nouns like Icelandic bardagi “battle.”

The derivation of baron from Germanic found the support of practically all later etymologists except, predictably, Settegast, who mounted a spirited defense of his old idea, but this time his voice was not heard. His reconstruction did not illuminate every dark corner (remember the asterisked forms, cited above!), but the Germanic reconstruction fares even worse. Settegast refuted the main objection to his theory (“baron” cannot go back to “fool”; of course, it cannot), so that there is no need to repeat the same seemingly crushing counterargument again and again. If Latin baro yielded not only “fool” but also “fighter,” from “a strong man,” then baro, as it occurs in Lex Salica, is a Latin noun.

In my rejection of the Germanic etymology of baron from berjask I am not quite alone. Pierre Guirot, a French etymologist who supports many untraditional solutions, returned to the idea that baron originated in Latin. Regrettably, he offered his opinion without offering detailed proof. Harri Meyer, a distinguished linguist but another maverick of Romance philology, tended to agree with Guirot. Clearly, the tide has not turned. But it does not follow that we have only two choices: either to derive baron from Latin baro or to trace it to Germanic berjask. There is at least one more possibility.

Etymology is a tale of eternal return. Old conjectures tend to resurface in a new light and make us look at forgotten or discarded ideas with interest and even respect. In the early sixties of the nineteenth century, the question was asked whether baron could be a continuation of some word like German Wehrmann “soldier.” Obviously, -on in baron and -mann in Wehrmann are not related. But what about Wehr “defense”? About seventy years later George G. Nicholson had an idea that returned him to Wehr, though, of course, he had no knowledge of an old exchange in Notes and Queries. He paid special attention to the common use of Old French baron with the genitive (“the baron of…”), for example, in li bon baron de France “the good defender, protector of France.” The English equivalent of the Latin phrase barones quinque portuum (which alternated with custodes quinque portuum) is Wardens of the Cinque Ports. In Old French, the word baron was applied to the king, saints, and even Jesus Christ, so that the sense “protector, defender” cannot be called into question.

Nicholson analyzed Old High German words whose English cognates are aware, beware, warn, ward, and warden (their root is war-), and derived baron from the reconstructed Romance form waronem-. The Romance languages did borrow the Germanic root war-, as testified, among others, by guardian, a doublet of warden. Waronem- “protector” would explain the well-attested sense of baron “man.” As mentioned in the previous post, the alternation w/v- ~ b- poses no insurmountable difficulties. Even the native Latin speakers noticed it, and a doublet of Spanish baron is varón “man, male.” The Portuguese form is similar.

Nicholson’s etymology invites serious consideration. Settegast was probably right in not considering “fool” the original sense of Latin baro, but he had a hard time of tracing the path from “a muscular man” to “fighter,” “man; husband,” and, finally, to “baron.” We may also concur with him that Italian barone “rogue” and barone “baron” continue the same Latin etymon. The association between baron and the cognates of Icelandic berjask does not look promising, and one should treat without much confidence the often-repeated statement that Latin had the word baro before the arrival of the Franks. It probably did not. More likely, baron is a Romance adaptation of Germanic waronem-. And couldn’t this coinage (baron) spread to the Celtic-speaking world? Old Irish bár “wise man, sage; leader; overseer,” especially “overseer,” resembles “protector,” the more so because one of the glosses of barons was Latin custodes (the plural of custos). In Ireland, the word might enjoy a shady existence as a legal foreignism, and, presumably, that is why it never occurred in native literature. If such was the state of affairs, barons emerged as protectors and “custodians.” The way from “protector” to “man; husband; fighter” is short. Thus, baron may be, after all, a Germanic word, but going back to an etymon quite different from the one mentioned in our dictionaries.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Alexander Girardi, austrian actor; seen in Johann Strauss II: The Gypsy Baron. Portrait Collection Friedrich Nicolas Manskopf at the library of the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt am Main. ID: S36_F08653. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A globalized history of “baron,” part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 6/11/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

baron,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

Henry Cecil Wyld,

baro,

beorn,

bearn,

salian,

franks,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Once again we are torn between Rome, the Romance-speaking world, and England. The word baron appeared in English texts in 1200, and it probably became current shortly before that time, for such an important military title would hardly have escaped written tradition for too long. One incontestable thing is that baron arose in Old French and through Anglo-French reached Middle English. At present, baron is the lowest rank in hereditary peerage, but “[t]he original meaning of baron in feudal times was one of a class of tenants holding his lands by military service from the king, or other superior lord. The term was soon restricted to king’s barons who were summoned by writ to the council. The practice grew up that those once summoned had a right to attend, and the honour and privilege became hereditary” (The Universal Dictionary of the English Language by Henry Cecil Wyld). The question is how this title happened to get the meaning recorded in Old French.

Early lexicographers were bold people: they formulated hypotheses and fearlessly proclaimed them, for nothing worse could happen to them than running afoul of a different politely formulated conjecture: no ridicule, no rebuke for violating phonetic laws (those had not yet been discovered) or missing an important publication (the few main books on the subject were widely known and always consulted). A look at the guesses by our distant predecessors is not devoid of interest, for some of them had a long life and are still with us.

The syllable bar occurs in many languages and not infrequently has a meaning that fits, at least to a certain extent, the meaning of baron. The first lexicographers noticed Hebrew bar “son,” recognized today even by those who have no knowledge of any Semitic language from bar mitzvah. Since for some time people traced all words to Hebrew, the alleged language of Paradise before Adam and Eve were banished from it, the tie between bar and baron seemed obvious. Then there was Old Irish bar “wise man, sage; leader; overseer.” For some reason, it frequently occurred in glossaries but did not turn up in any text, literary or legal. Such words occur in many old languages and look like learned concoctions. Still this bar, whatever its origin, has been attested, so probably it is not a figment, as James Murray suspected. Charles Mackay, whose etymologies are fanciful but forms invariably correct, mentioned the obsolete Irish Gaelic bar “a man, a learned man” and baran “a great man.” He hardly knew them from living speech.

Then there is Old Engl. beorn “man; hero; warrior,” which may be the same word as one of the Old Germanic names of the bear (this is uncertain; yet the alternative derivation from the verb bear is less likely). Bestowing the names of ferocious animals (bears and boars, for instance) on doughty fighters and esteemed chiefs was common practice. Old Germanic poetry is full of relevant examples. Next to it we find Old Engl. bearn “child, bairn,” an unquestionable cognate of the verb beran “to bear.” Beorn and bearn suggest a Germanic origin of baron, even though the details of the development are unclear.

We can now turn to Latin vir “man, husband,” often proposed as the source (etymon) of baron. Vir has respectable cognates in Old English and Gothic (nearly the same form and the same meaning). The alternation v ~ b poses problems, but they are not insurmountable. It is the suffix (or what looks like a suffix) -on that defies an explanation if we begin with vir. However, some of the best etymologists of the first half of the nineteenth century ignored the “suffix” and had no doubts about vir being the etymon of baron. Vir is not the only v-word that surfaced in the etymological explanations of baron. Latin varus “knock-kneed, bow-legged” and vara “a forked pole,” a cognate of varus, have also been referred to. The connection between them and baron is tenuous at best.

More promising is the Latin noun baro (genitive baronis, accusative baronem), which looks like a possible source of baron. However, the history, and not only the etymology, of baro is another hornets’ nest. The most baffling fact is that there seemingly were two Latin words baro. One had length on both vowels and is usually glossed as “fool; simpleton.” This is the meaning Cicero and at least one more author knew. The other baro, which is given in the most authoritative dictionaries of Latin with a short root vowel, meant “a free man” (that is, not a serf), but it emerged late, in a law code known as Lex Salica “Salian Law.” The code was put together at the beginning of the sixth century, in the reign of Clovis I, though no manuscripts antedating the eighth century have come down to us. The code regulated the life of the Salian Franks. The etymology of the name Salian is debatable and should not concern us. We only need to know that the Salian Franks were different from the so-called Ripuarian Franks and that later the same laws governed all of them. The Franks were a conglomeration of Germanic tribes.

More promising is the Latin noun baro (genitive baronis, accusative baronem), which looks like a possible source of baron. However, the history, and not only the etymology, of baro is another hornets’ nest. The most baffling fact is that there seemingly were two Latin words baro. One had length on both vowels and is usually glossed as “fool; simpleton.” This is the meaning Cicero and at least one more author knew. The other baro, which is given in the most authoritative dictionaries of Latin with a short root vowel, meant “a free man” (that is, not a serf), but it emerged late, in a law code known as Lex Salica “Salian Law.” The code was put together at the beginning of the sixth century, in the reign of Clovis I, though no manuscripts antedating the eighth century have come down to us. The code regulated the life of the Salian Franks. The etymology of the name Salian is debatable and should not concern us. We only need to know that the Salian Franks were different from the so-called Ripuarian Franks and that later the same laws governed all of them. The Franks were a conglomeration of Germanic tribes.

Although Lex Salica was written in Latin, the word baro could be a Latinized German word. Untranslatable native terms regularly appeared in medieval Latin texts unchanged (occasionally -us would be added to them, and Alemannic barus has been recorded). If the word is German, we find ourselves on familiar ground (compare bearn and beorn mentioned above), but if it is Latin, we have to decide whether it has anything to do with baro “fool; simpleton” and ideally account for its origin. Baro “fool” has a well-known continuation in the Modern Romance languages. Italian barone means both “baron” and “rogue,” and many similar-sounding nouns with various suffixes have related meanings, “urchin” among them. “Simpleton,” let alone “fool,” could not develop into “a king’s man” or something similar. Most modern dictionaries state that baro1 and baro2 have nothing to do with each other, but the German linguist Franz Settegast thought differently and made an attempt to overthrow this conclusion.

Settegast showed that in some Latin books baro designated a strong (muscular) or an unpolished man, a hillbilly, a man from the boondocks, as we might say. His findings have never been refuted, but the question remains which sense is original and which is derived, that is, whether the path was from “fool” to “a strong man” or from “a strong man” to “fool.” Also, some etymologists say that Italian barone “rogue” and barone “baron” are different words (homonyms) and cite plausible sources for both, while others try to connect them. As could be expected, the definitive answer does not exist, but the situation may not be quite hopeless, and next week I’ll say what I think about it.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Manuscrit de la loi salique datant de 793, bibliothèque de l’abbaye de Saint-Gall. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A globalized history of “baron,” part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 6/22/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

autism,

Leisure,

baron,

festival,

Early Bird,

jerry coyne,

hay festival,

asperger,

cohen,

hay-on-wye,

priya gopal,

simon baron-cohen,

steve jones,

gopal,

coyne,

Literature,

UK,

Current Events,

A-Featured,

literary festivals,

Add a tag

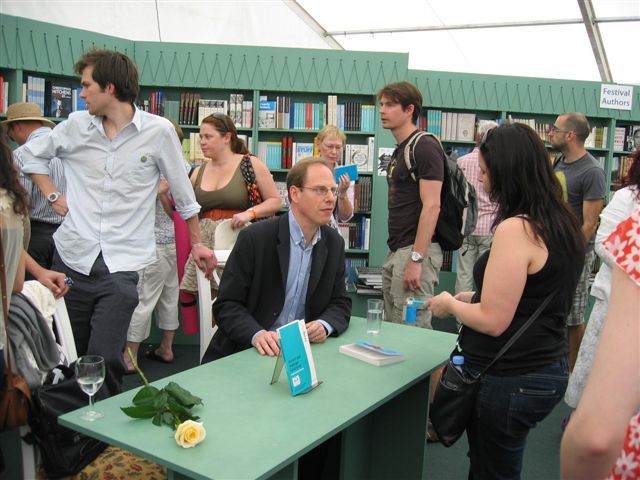

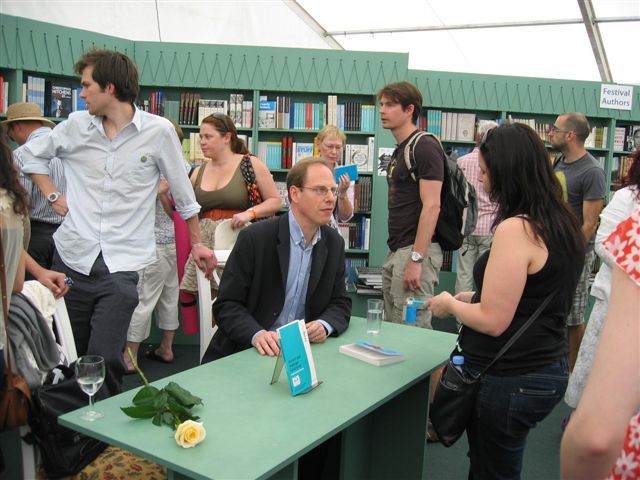

A couple of weeks ago I brought you a post on the Hay Festival by OUP UK’s Head of Publicity Kate Farquhar-Thomson. Today, for those of you who couldn’t make it to the Festival (like me), here are some of Kate’s photos from the few days she spent there.

The festival site from on high

Priya Gopal, author of The Indian English Novel, speaks to a festival-goer

Scientists Steve Jones and Jerry Coyne. Coyne’s book Why Evolution is True was published by OUP in the UK.

Festival-goers on site. Doesn’t it look glorious?

Simon Baron-Cohen, author of Autism and Asperger Syndrome: The Facts, signs books.

By:

Trisha, Gayle, and Jolene,

on 2/25/2008

Blog:

The YA YA YAs

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Fiction,

funny books,

Asian-Americans in YA Lit,

she's so money,

cherry cheva,

Asian-Americans in YA Lit,

cherry cheva,

funny books,

she's so money,

Add a tag

High school senior Maya works at her parents’ restaurant, takes a ton of AP classes, and tutors “students who are…not so much like” her, as Principal Davis puts it. Unfortunately for Maya, the student she had been tutoring just got an A on his latest math test and his parents refuse to pay for any more tutoring. So Principal Davis assigns Maya to another student. Camden King. Ew.

High school senior Maya works at her parents’ restaurant, takes a ton of AP classes, and tutors “students who are…not so much like” her, as Principal Davis puts it. Unfortunately for Maya, the student she had been tutoring just got an A on his latest math test and his parents refuse to pay for any more tutoring. So Principal Davis assigns Maya to another student. Camden King. Ew.

Camden King is rich, hot, popular, lazy, and generally content to coast along on these traits alone. During his second “tutoring” session with Maya, he offers her $100 to do his math homework. Good girl that she is, Maya refuses. But when her parents leave her in charge of their restaurant, setting off a chain of events that leads to a $10,000 fine from the Health Department, Maya freaks out.

Maya knows that cheating is wrong, but she fears the alternative is worst. Afraid her family can’t afford the fine and believing that since it’s her fault, she should be responsible for paying it off, Maya thinks doing Camden’s homework is the only choice she has if she wants to pay off the fine without her parents finding out about it. When Camden tells a couple of his friends that he’s paying someone to do his homework and they want in, Maya recruits a couple of her friends to help do all the homework, and the whole thing turns into a cheating ring.

It’s only February, but Cherry Cheva’s She’s So Money gets my vote for funniest book of the year. Who knew a book about 1) a smart good girl and 2) cheating could be so hilarious? (Although—and I think this should be totally obvious, but I’m going to say it anyway—if you don’t think cheating should ever a laughing matter, you should probably skip this book.) While the book is seriously funny, it never devolves into slapstick or being funny just for the sake of being funny. The humor gives us insight to the characters, and it’s the kind of sarcastic and, okay, rather sitcomish funny repartee you always wished you were capable of coming up with in your own life.

“Nice butt,” Camden said from behind me. I quickly sat up. “Too bad your personality doesn’t match it,” he added.

“And too bad your brains don’t match your dad’s bank account,” I shot back. “If they did, we wouldn’t be here.”

Camden stared at me for a moment, opening his mouth and then closing it again before breaking into a grin. “Wow,” he finally said as he got out a mechanical pencil and started clicking it noisily. “You’re an interesting one. Most girls are so stunned by this whole business”—he waved the pencil at himself—”that they can’t even attempt to be bitchy.”

“Well, I’m not and I can,” I said.

“I don’t know if I like you or hate you.”

“Hate me. It’ll make us even,” I said. “Now shut up and open your math book.”

And do you know how hard it was to pick just one part to quote? (Okay, two, with the line from Principal Davis.) Again, this is one funny book. But… She’s So Money is also one of those books that I really enjoyed as I read it but did not quite hold up upon further reflection. Don’t get me wrong, I still like the book a lot and, obviously, think it’s an absolute riot, but I somehow didn’t love it *after* finishing it the way I loved reading it. If that makes sense. Still, I am definitely looking forward to more books by Cherry Cheva, and I’m sure teens will, too, once they’ve read She’s So Money.

Read an interview with Cherry Cheva at the HarperTeen site. Also reviewed by Reader Rabbit and The Story Siren.

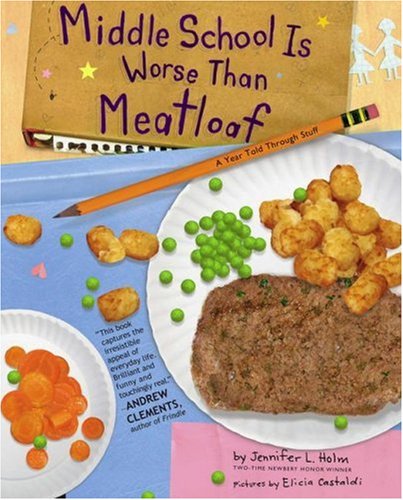

Today I’m giving you a poem that made me laugh out loud from an excellent, funny book, Middle School is Worse Than Meatloaf, by Jennifer Holm.

Today I’m giving you a poem that made me laugh out loud from an excellent, funny book, Middle School is Worse Than Meatloaf, by Jennifer Holm.

I think you should get a badge

for not smacking

your bratty little brother

when he eats the charms

off your bracelet because

he thinks it will give

him super powers.

I think you should get a badge

for taking the blame

about shaving the cat

when it was

your weird older brother who did it.

I think you should get a badge

for not crying when

your new stepfather

forgets to pick you up

after school

and Mary Catherine Kelly

gets the part

of the Sugarplum Fairy.

I think you should get a badge

for all these things,

but the Girl Scouts

don’t agree with me.

Man, those last lines crack me up. Really the whole book is funny and interesting and

so very different. The subtitle is

A Year Told Through Stuff, and that phrase explains it perfectly. The book covers a difficult year for Ginny as she starts middle school, gains a stepdad, loses a friend, makes a friend, changes her look, deals with brothers and endures disappointment. But the whole book is told through... well,

stuff. Notes, an ad, a school schedule, a bank statement, poems, essays, flyers, horoscopes, receipts, and on and on. It’s brilliant storytelling and a fresh, new way to convey events. Great example: On one page we see an article on five ways to look pretty that includes coloring your hair. On the same page is the box of a hair coloring product and a receipt from a drugstore. Now, turn the page, and we have a receipt from a hair salon for “hair color treatment (color reversal from red to blond)” along with “haircut and style (to remove burned ends).” And if that weren’t enough humor for you, then the next page has a change to Ginny’s Big To Do List with “Look good in the school photo for once!!!” crossed out, and “Why bother!!! (maybe next year)” now noted.

I loved this innovative approach to charting a year, and props go out to Elicia Castaldi for the pictures. My sixth grade daughter (not middle school here, but still) really enjoyed the book too. I gave it to her and she read it straight through, right then, as opposed to her usual preteen way of half-heartedly taking the book from me with an implied eye-roll, tossing it beside her bed, and ignoring it for two weeks. So, that’s gotta mean something, right?

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

More promising is the Latin noun baro (genitive baronis, accusative baronem), which looks like a possible source of baron. However, the history, and not only the etymology, of baro is another

More promising is the Latin noun baro (genitive baronis, accusative baronem), which looks like a possible source of baron. However, the history, and not only the etymology, of baro is another

6th grade IS middle school, even if they're not at the building yet.

Book sounds awesome. Thanks for the poem :)

Heh.

The Girl Scouts -- and the Pathfinders, which was our girl/boy version of said same -- didn't agree with a LOT of things for which I thought I ought to have a badge...

Now be careful, you are talking to a Girl Scout leader here.

Of course, that's why the end kinda cracked me up.

That poem has such a rich voice. Thanks for sharing.

Very cute.

Have you submitted for the pic bk carnival over at my blog yet?

I think you should get a badge for all those things, too! The Girl Scouts gave me a badge for IRONING, and what use is that? Losing out on the sugar plum fairy gracefully, now that's a skill.

I meant to pick that book up yesterday, but didn't make it to the store. I'll get it today, though, for sure — it's made of awesome. (Like the page where she's clipped a magazine article that suggests a bubble bath and new haircolor, and the following page with its receipts to repair lots of damage caused by both.)