new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Authors &, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 232

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Authors & in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Marissa Wasseluk,

on 9/19/2016

Blog:

First Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

community,

Diversity,

Books & Reading,

Authors & Illustrators,

culture,

Guatemala,

America,

English,

immigrants,

Korea,

Anne Sibley O'Brien,

Somalia,

TESOL,

Stories for All,

Expert Voices,

I'm New Here,

welcoming week,

Add a tag

Welcoming Week is a special time of year. Communities across the country will come together to celebrate and raise awareness of immigrants, refugees and new Americans of all kinds. Whether it’s an event at your local art gallery or showing support on social media, the goal is to let anyone new to America know just how much they are valued and welcomed during what is likely a big transition.

And the biggest transitions are happening for the littlest people.

A new country, a new home, maybe even a new language — that would be enough for any kid — but a new school, too? That subject is exactly what author Anne Sibley O’Brien addresses in her book I’m New Here, new to the First Book Marketplace.

Marissa Wasseluk and Roxana Barillas of the First Book team had the pleasure of speaking with Anne about I’m New Here, the experiences of kids new to America, and what kids can do to help create a welcoming atmosphere.

Marissa: So, and I am sure you get this question all the time, but I’m curious — what inspired or motivated you to create I’m New Here?

It’s funny, it’s such a, “where would you start?” kind of question, but I don’t remember if anyone has ever asked me that point blank because I don’t recall ever putting together this answer before. Over the years of working in schools — especially working with Margy Burns Knight with our nonfiction books: Talking Walls; Who Belongs Here and other multi-racial, multicultural, global nonfiction books — I had a lot of encounters, a lot of discussions, a lot of experiences with immigrant students and I was very aware of the kinds of cross-cultural challenges that children and teachers can experience. For instance, Cambodian children show respect by keeping their eyes down and not looking in the eyes of an adult, especially a teacher. In Cambodian culture adults don’t ever touch children’s heads. So you can immediately imagine how those kinds of things would be quite challenging when a Cambodian child comes into a U.S. classroom and suddenly two of those cultural markers are not only gone, but the opposite is what they need to learn.

Somebody might put their hand on your head — it being out of concern and wanting to make a connection — or they might say “I need you to look at me now” and not recognize that that’s cultural inappropriate for a Cambodian child. So growing that kind of awareness of the challenges that immigrant children face — that was the original impetus for the book. Just collecting some of those stories and raising awareness of how many obstacles immigrant children face. From climate to traditions in speaking and in body language, to food, to learning a new language. Not just learning a new language in terms of how you speak and read and write, but also how you interact with people, how social norms work — they just face such enormous challenges. And there were originally six characters so it was trying to cover everything.

Marissa: The characters that are in the book, they cover a child from Guatemala, a child from Korea, and a child from Somalia — did you work with these specific immigrant communities when you were creating this book?

I spoke to individual experts, such as several Somali interpreters and family liaison experts who work for the multi-lingual, multicultural office of the Portland, ME public schools. So I had that kind of expert advice to respond to what I was writing. But the original ideas mostly came from my observations, my interactions with Somali students in the classrooms that I visited. And then with Korean students I met many, many Korean students here in the US and I had my own background to draw on there.

Marissa: Can you tell me a little bit more about these classrooms that you’ve visited? We talk with a lot of educators who work with Title I schools and they often talk about how reserved the English as a second language students can be. There is a silent phase that a lot of kids go through. Have you observed that and have you shared your book with any of these first generation immigrants?

It’s certainly been shared with many. I actually just shared it with a group of students in a summer school program — about seventy students from third to fifth grade who were from East African countries and some Middle Eastern countries. Most of the group were immigrants and I read the book and then we had a discussion about being new and being welcoming. Of all the student groups that I’ve worked with, they were actually the most effusive and had the most to share in that discussion about what it feels like to be new and what you can do to welcome someone.

Marissa: What were some of the suggestions?

They had all kinds of ideas about what you could say and do to make somebody feel like they were at home. You could take them around, go through a list and say, “this is your classroom, this is your teacher, this is your playground, this is your classmate.”

Roxana: You’re taking me back – a few years back I came to the United States when I was twelve from El Salvador, speaking no English. It hits close to home in terms of the importance of the work you are doing, not just for kids who may not always feel like they belong, but also for the kids who can actually help that process be an easier one.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

That is wonderful to hear. I was just struck that they had more suggestions than any group I’d worked with, they could hardly be contained. They had so much they wanted to say and I think it’s very fresh in their minds what welcoming looks like and maybe what did or what didn’t happen for them. So the list that they wrote: welcome to my class, say hi, wave, smile, hello, say this is my classroom, these are my friends, do you want to become friends? these are my parents, this is my family, show them around, this is my chair, this is my house, this is your school, this is my teacher, can you read with me? how’s it going? I live here, where do you live? do you need help? welcome to my school.

It was the specificity of it that I just loved.

And they said what it felt like to be new. These kids went beyond with the details so they said: scared, nervous, confused, happy, sad, lonely, shy, surprised. Which is what I get with any group that I talk to — but then they wrote: don’t know how to write, don’t know everybody, don’t know what to do, don’t know what they’re saying, don’t know what to say, don’t think you fit in, embarrassed, don’t know how to read books, don’t know what to think, don’t know how to play games, don’t know how to respond, don’t know how to use the computer. So that is a really rich, concrete list.

Marissa: What about educators, how have educators responded to your book?

It’s been pretty phenomenal. The book is in its third printing and it’s just a year old. Actually, it went into its third print run in June. That is by far the fastest that any book of mine has taken off, so there seemed to really be a hunger. There are quite a number of books about an individual immigrant’s story, but I think what people are responding to, what they found useful, is that this book is different because it’s a concept book about the experience of being new and being welcoming, and in that way it works. A particular story can make a deep connection even if your experience is quite different, you recognize things that are similar. But to have one book that outlines what the experience is like, it is very good for discussions. I’ve done more teacher conferences and appearances, especially in the TESOL community, than I did before. Normally I do a lot of schools where I talk to students, but in the past year the majority of my appearances have been for teacher conferences.

Marissa: Have any of them come up to you and told you how it’s resonated with them? Have you met any educators who are immigrants themselves?

Yes, definitely! The TESOL community is full of people who have immigrant backgrounds. I shouldn’t say full, but there is quite a healthy percentage of the TESOL community who come from that background themselves. Partly because schools often recruit someone who’s bilingual, so you tend to get a lot of wonderful richness of people’s life experiences. They might be second generation or they might not have come as a child but they definitely make a strong connection to children who have that experience. I remember, in particular, some very moving statements that people made standing in line waiting to have a book signed. Talking about how it was “their story” or people talking about and being reminded of their own students. When I talked about the book they were in tears thinking about their own students.

Marissa: Ideally, how would you like to see your book being used in a classroom or a child’s home?

I think I see it in two ways. First, for a child who has just arrived and who is in a situation where things are strange; to be able to recognize themselves and see that their experience is reflected in something that makes them feel less lonely and that there is hope. Many, many people have gone through this experience and it can be so difficult but you can get through.

And to the children who are not recent immigrants, who have been part of a community for generations; that it would spark empathy for children, for them to imagine what it would be like if they had that experience. Starting with that universal experience of somehow being new somewhere and to recognize, “oh, I remember what that felt like” and imagine if it was not only a new school, but a new country and a new language and a new culture and new food and new religions and on and on and on. Particularly for them to imagine what they could do, concretely, to examine what the new children are doing and to see how hard they are working, the effort that they are making. And also how their classmates are responding so that the outcome is the whole group building a community together.

To learn more about I’m New Here and Anne’s perspective, watch and listen as she discusses the book and her insights into the experiences of immigrant children.

The post Welcoming Week: Q&A with Author Anne Sibley O’Brien appeared first on First Book Blog.

By: Marissa Wasseluk,

on 8/19/2016

Blog:

First Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books & Reading,

Authors & Illustrators,

author interview,

Jason Reynolds,

stories for all,

diverse books,

all american boys book,

author jason reynolds,

ghost book,

Add a tag

Author Jason Reynolds’ books start the conversations about the difficult issues facing kids today. His experiences, as told through the characters in his stories, are very much like those of the children we serve – which is why we feel it’s so important for them to hear Jason’s voice.

We had the opportunity to talk with Jason about his experiences, his journey to becoming an author, and how he’s seen his books affect young readers.

Q. Were you an avid reader as a child?

A. Absolutely not. I actually didn’t read much at all, though I had books all around me. Most of them were classics. Canonical literature. But to a kid growing up in the midst of the hip-hop generation, a time where most young people of color were exposed to the hardships of drugs and violence, I gravitated more toward the storytelling of rap music, than I did the dense and seemingly disconnected narrative arc of books (during that time).

Q. What stories or poetry did you connect with as a young person? Did you have trouble connecting with stories as a child?

A. I had a really hard time connecting with stories as a child, especially within the confines of a book. But I was introduced to poetry by reading the lyrics of Queen Latifah, Tupac, Slick Rick, and lots of other rappers. From there, I started to make connections between their lyrics and the poetry of Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou. But eventually I began reading more traditional narratives, the first being Black Boy, by Richard Wright. It changed my life.

Q. Are there books you’ve read today that you wish you’d been exposed to as a child or young adult?

A. All of Walter Dean Myers’s work. Also, I wish there would’ve been as much focus on graphic novels back then, as there is now. That would’ve been extremely valuable to me.

Q. We first met you as a writer through your poetry in My Name is Jason. Why did you make the transition into writing novels? And how is your process for writing poetry different than writing novels?

A. I never wanted to write novels, so you can blame Christopher Myers for that. He’s the one who challenged me to give it a shot. My plan was to be only a poet. But there was something in Walter Dean Myers’s stories — a permission to be myself on the page I hadn’t felt before. So I let myself be myself, let my language live freely on the page without the pretense and pressure of the academy or some phantom scholarship. And turns out, it worked! Now, the poetry was a big help mainly because as a poet I valued the importance of beginning and ending, which has lent itself to my work tremendously.

Q. You toured extensively with Brendan Kiely for All American Boys. Can you recount a few of the most powerful moments you had with students and/or with adults while on tour?

There were so many. One thing that was interesting was, everywhere we went we would ask the students the same two questions:

1.) How many of you know about police brutality? They’d all raise their hands. And,

2.) How many of you have spoken to your friends about it? Ninety percent of the hands went down.

We realized that kids knew about it but weren’t discussing it, but we also deduced that it wasn’t because they didn’t want to talk about it, but instead was because they didn’t have the framework or the safe space to do so. By the end of our presentation, everyone always had questions and comments, ready for the hard conversation. Some other interesting moments . . . We met a man in Cincinnati, a white man raising two black boys. He came over to us and explained that All American Boys had helped him understand what his sons might be facing outside of his home, and that he needed to be as open as possible and as emotionally and mentally equipped so that he could serve as not only their father, but as their ally. He even said reading the book helped him feel more whole. I also had a student come to me, a young black girl in Philly, who wanted to know if I ever wished I could change the color of my skin, just because she was afraid of the fear other people have of it. She was in the seventh grade, and in that moment I got to pour into her. Tell her that she was perfect the way she was. I have tons of these stories. Mexican kids in Texas who wondered what their role is. Wealthy white boys in Baltimore forming cultural sensitivity groups in their schools. Even recently watching a group of students perform the theatrical version of All American Boys in Brooklyn. Young people are ready to talk. And they’re ready to act. We (adults) just have to arm them.

Q. Do you see your teenage self in any of your novels? If so, which one(s) and in what ways?

Q. Do you see your teenage self in any of your novels? If so, which one(s) and in what ways?

A. I’m in all of them. Each and every one of them. I like to pull from actual stories from my teenage years, like Ali and the MoMo party in, When I Was The Greatest, or Matt Miller and his mother’s cancer in, The Boy in The Black Suit. I’m always the protagonist, at least parts of me. Writing is cathartic for me, and a way to process parts of my life that I’ve either worked hard to hold on to, or have desperately tried to forget.

Q. How important was it to have a co-author for Quinn’s voice in All American Boys?

A. It was paramount. The truth is, I might’ve been able to write a decent book, based around Rashad’s narrative, but what Brendan brings to the story with Quinn is, to me, the most important part of the story. It’s the part we don’t hear about, and the part most necessary to sit with and dissect when it comes to making change. It’s something I’m not sure I could’ve written with the same authenticity as Brendan, and I couldn’t have asked for a better partner on that project.

Q. Why do you feel it’s important for kids of varied backgrounds to read the stories you write?

A. You know, I think about this often, and I think ultimately what I hope is that they read my books and feel cared for. Feel less alone. There’s an impenetrable power to simple acknowledgement.

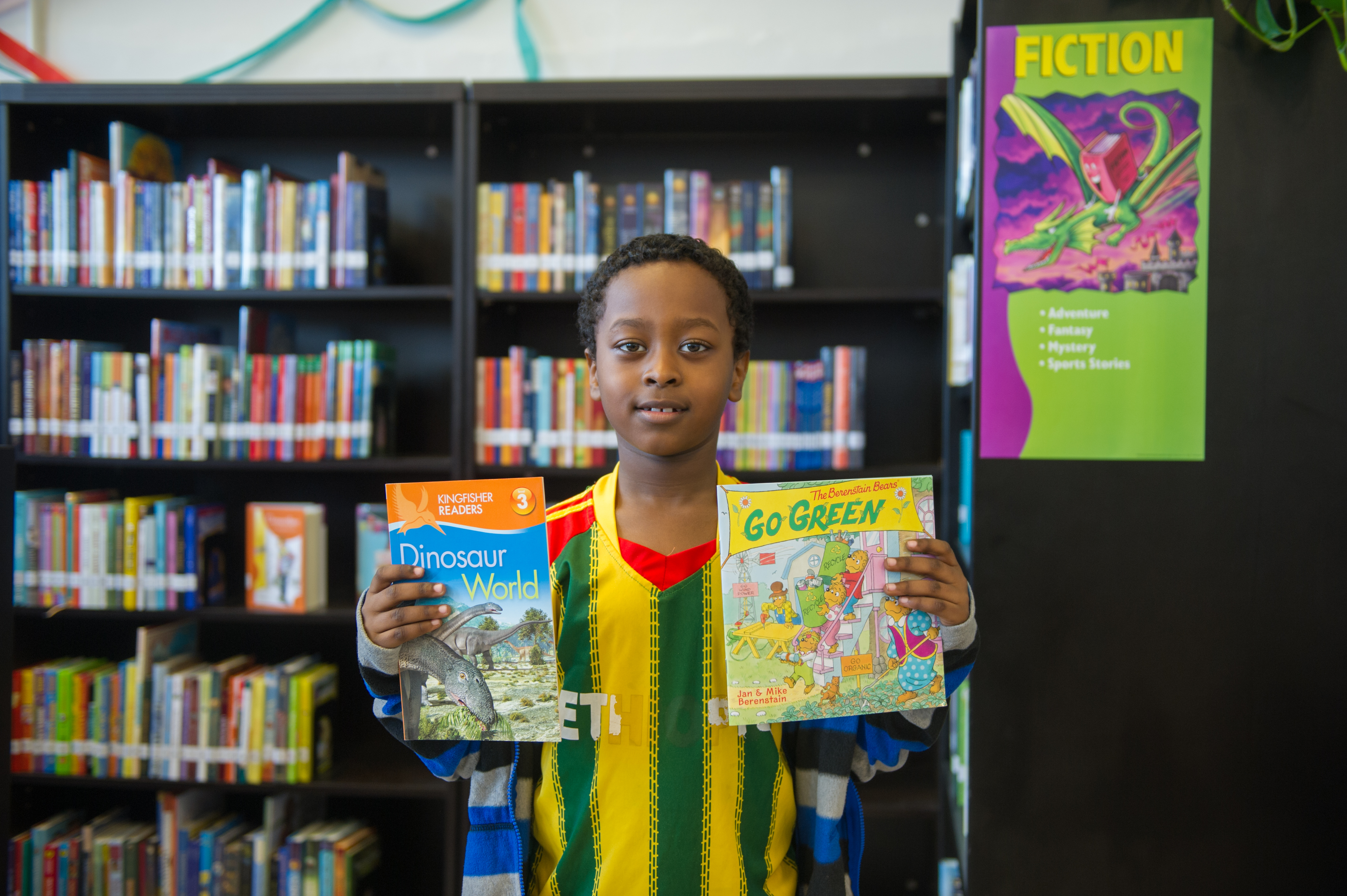

Q.Why is it important for kids, especially kids from low-income communities, to have access to brand-new books?

A. It’s important for kids from low-income communities to have brand-new anything. But if it could be a book, let alone a book that speaks directly to their experiences, then it’s a double-win.

Watch the video below for more insights from Jason:

Thanks to the support of Jason Reynolds’ publisher, Simon & Schuster, 20,000 of Reynolds’ young adult and middle grade titles will be distributed to children in need through First Book.

The post Q&A with Author Jason Reynolds appeared first on First Book Blog.

By: Samantha McGinnis,

on 5/31/2016

Blog:

First Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Raymie Nightingale,

National Summer Reading Champion,

Authors & Illustrators,

author interviews,

Kate DiCamillo,

Beverly Cleary,

Because of Winn-Dixie,

CSLP,

Expert Voices,

Collaborative Summer Library Program,

imagination in books,

libraries,

Laura Ingalls Wilder,

summer reading,

The Tale of Despereaux,

Stuart Little,

summer library programs,

Add a tag

This summer, kids can access great books, go on adventures to faraway places and even win prizes – all at their local library.

Kate DiCamillo, author of Because of Winn-Dixie, The Tale of Despereaux and the recently released Raymie Nightingale, appreciates the importance of reading – especially during the summer.

As she visits schools throughout the country, answering questions about her new character Raymie and her journey to conquer remarkable things, she’s also letting kids know that all summer long their local libraries offer great opportunities for summer fun as the 2016 Collaborative Summer Library Program (CSLP) National Summer Reading Champion.

We had the opportunity to talk to Kate about what inspired her to become a children’s author, the importance of books and imagination and which books she loved to read during summer break as a kid.

Your books are very imaginative. Why is important for kids to explore their imagination through books?

Because you find that anything is possible – and the feeling of possibility gets into your heart. That’s what books did for me.

As a kid, I was sick all the time and spent so much time alone. It was super beneficial to read because I was convinced that the things I didn’t think were possible actually were! That’s incredibly important for kids in need, but also for all of us.

Your stories are very relatable for children. Why is it important for kids to see parts their lives in the books they read?

Your stories are very relatable for children. Why is it important for kids to see parts their lives in the books they read?

I feel this as an adult reader too. Books give me an understanding not only of the world and other people’s hearts, but my own heart. When you see yourself in a story, it helps you understand yourself.

During my school visits, so many kids tell me stories of how they connect with my characters – Despereaux and Edward Tulane and Raymie. It’s so humbling to see that connection.

And when you see other people, it introduces you to a whole new world. I think of a story I read as a kid, which was actually just reissued, called All of a Kind Family. It’s about a Jewish family in turn-of-the-century New York. That couldn’t have been more foreign to me growing up in Central Florida but I loved every word of it.

Did you like to read during the summer as a kid?

Yes! I loved reading. I could spend all day reading. I’d go up into my tree house with books and sometimes didn’t come down until dusk.

If you gave me a book as a kid, I loved it. I read without discretion. But I did have my favorites I’d come back to again and again: Beverly Cleary’s books, Stuart Little and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books.

It’s so crazy to stand in front of groups of kids and tell them this. There’s always a murmur of “oh, yeah, yeah! I read that!” That’s the staying power of books.

How can kids access books and learning activities over the summer?

That is the beautiful thing about CSLP summer reading programs at public libraries: it makes it easy for parents, caretakers and kids themselves to access all kinds of materials and activities for free. The 2016 summer reading theme is “On your mark, get set, READ!” and I think that’s an open invitation to readers of all ages to take advantage of everything their library offers.

Want more Kate DiCamillo? Listen to her talk about the fantastic summer fun you can find at your local library!

The post Author Kate DiCamillo Finds Summer Fun at The Local Library appeared first on First Book Blog.

By: Samantha McGinnis,

on 4/5/2016

Blog:

First Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Judy Moody,

National School Library Month,

Expert Voices,

Association of School Librarians,

Judy Moody and Stink,

libraries,

librarians,

Authors & Illustrators,

Megan McDonald,

Add a tag

Today’s guest blog post is by bestselling children’s author Megan McDonald, 2016 Spokesperson for the American Association of School Librarians National School Library Month.

Imagine a school without a library.

A few years back, I was honored to be a visiting author in elementary schools in the state of Florida. After school one day, I was signing books at a table outdoors, because the school did not have a library.

A grandmother waited patiently in line, kids tugging at her. When she reached the table where I was sitting, she held out a well-worn, much-loved copy of my very first book, Is This a House for Hermit Crab?

With tears in her eyes, she told me about the many children, and now grandchildren, she’d taught to read using my book—because it was the one, the only, book they owned at their house.

The school library gave me my start as a reader, and as a writer. It was through my school librarian that I first met Ramona and Homer Price, Laura Ingalls Wilder and Stuart Little, the Melendys and the All-of-a-Kind Family.

Without them, my characters Judy Moody and Stink would not exist.

I want all kids to experience the magic of libraries. I want them to build log cabins out of Popsicle sticks and start their own Independent Saturday Afternoon Adventure Clubs and save the world ala Judy Moody. I want them to grow up to become readers and writers, artists, thinkers, inventors.

But for this to happen, we have to connect kids with books. We have to change lives with books.

First Book is doing just that!

First Book supports educators working in low-income communities with new books and educational resources. By signing up with First Book, school librarians can access affordable, relevant, best-in-class books for all readers, including reluctant readers.

School libraries are the heartbeat of the school. They serve as a resource to all students and support both required and independent reading. They shape lives. Join me in celebrating school libraries and highlighting the important work that school librarians do to transform kids’ learning.

Head for the school library. Seek out a book from First Book.

Anyone working in the lives of kids in need can sign up with First Book at www.firstbook.org/join.

The post Imagine A School Without A Library appeared first on First Book Blog.

April 12, 2016 marks the one hundredth birthday of children’s literature icon Beverly Cleary. To celebrate, the March/April 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine includes a series of tributes to the author and her work written by children’s book authors, illustrators, editors, and librarians whose lives and work were touched by Ms. Cleary.

April 12, 2016 marks the one hundredth birthday of children’s literature icon Beverly Cleary. To celebrate, the March/April 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine includes a series of tributes to the author and her work written by children’s book authors, illustrators, editors, and librarians whose lives and work were touched by Ms. Cleary.

Beth McIntyre, Madison County (WI) Public librarian, shows off her Ramona Quimby Q tattoo.

Each week leading to The Big Day we’ll post an article or two about Cleary’s life and work. To start things off, here is Julie Roach, from the Cambridge (MA) Public Library talking about “Ramona in the 21st-Century Library” — including bonus Ramona-inspired tattoo!

Happy 100th Birthday, Beverly Cleary! For more, click the tag Beverly Cleary at 100 and read the March/April 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The post Happy 100th Birthday, Beverly Cleary! appeared first on The Horn Book.

“‘Oh, did people write that in those days, too?’ Beezus was surprised, because she had thought this was something very new to write in an autograph album…” (Beezus and Ramona)

“‘Oh, did people write that in those days, too?’ Beezus was surprised, because she had thought this was something very new to write in an autograph album…” (Beezus and Ramona)

Sometimes a book becomes quickly dated, and sometimes it easily crosses decades or generations. Beezus finds this is also true for autograph albums, and she makes an important parallel discovery that brings her much hope for the future: her mother and beloved aunt grew up to be close, though they fought as children as intensely as she and Ramona do. (Aunt Beatrice ruined Mother’s autograph album by signing every page!) It is okay not to love one’s little sister all the time. These days, autograph albums may be out of fashion, but the theme of sibling rivalry never goes out of style.

Beverly Cleary published Beezus and Ramona sixty-one years ago. At the Cambridge Public Library in Massachusetts, where I manage youth services and oversee youth collection development, I checked in on Ramona in the twenty-first century.

Beverly Cleary published Beezus and Ramona sixty-one years ago. At the Cambridge Public Library in Massachusetts, where I manage youth services and oversee youth collection development, I checked in on Ramona in the twenty-first century.

The city of Cambridge has a diverse population that truly supports and uses its public libraries. The Children’s Room in particular is a fantastic community gathering space where kids from all backgrounds come alone or with friends or family to read and make discoveries. For the past decade, our Children’s Room book circulation has grown significantly every year, and almost fifty percent of the total number of items goes out every month. We strive to have something for each reader, with multiple copies of the books that “everyone” is reading. We want all children to find books with characters and situations they can relate to and recognize as well as books with characters and situations unlike those they know. As much as possible, we want readers to be able to find both the book they came in for (even if it is very popular) along with the one they did not know they wanted.

How does Ramona fare in such an environment?

Each of our six branches owns copies of Beverly Cleary’s books, and the Main Library owns extra copies of each — ten copies of the most popular titles — and audio editions and some versions in other languages. Beverly Cleary’s books all circulate multiple times a year, with Ramona’s titles going out more than the others. The Ramona audiobooks, engagingly performed by Stockard Channing, circulate even better than the printed books. Twenty-first-century characters who are often compared to Ramona — such as Sara Pennypacker’s Clementine, Lenore Look’s Alvin Ho, and Megan McDonald’s Judy Moody and Stink — are in high demand at our library, but over the past year the print versions of Ramona held ten to twenty percent higher circulation figures than those other series.

Each of our six branches owns copies of Beverly Cleary’s books, and the Main Library owns extra copies of each — ten copies of the most popular titles — and audio editions and some versions in other languages. Beverly Cleary’s books all circulate multiple times a year, with Ramona’s titles going out more than the others. The Ramona audiobooks, engagingly performed by Stockard Channing, circulate even better than the printed books. Twenty-first-century characters who are often compared to Ramona — such as Sara Pennypacker’s Clementine, Lenore Look’s Alvin Ho, and Megan McDonald’s Judy Moody and Stink — are in high demand at our library, but over the past year the print versions of Ramona held ten to twenty percent higher circulation figures than those other series.

Cleary shelves at the Cambridge Public Library. Photo: Lolly Robinson.

Numbers can only tell so much, so I asked the parent/child book group I facilitate what they think. This group consists of about twenty people, ten kids between the ages of seven and ten and usually their ten grownups (although we can and do have kids who join solo). The group includes boys and girls from different schools and a wide range of backgrounds, and everyone — child and adult — reads and participates. Their varied takes on the books we read consistently blow my mind, and they are quite practiced at telling me how they really feel about what they are reading.

I let everyone know about the article I was writing and casually asked, “Have any of you ever read the Ramona books?”

All hands shot up and enthusiastic chatter erupted around the table.

When I asked if they remembered how they first discovered the Ramona books, I got an interesting assortment of answers. One girl’s mom read them to her. Another found out about them from a school friend.

One boy said, “My librarian at school gave me that book about Ralph. The mouse? And then I found the Ramona books next to it on the shelf. And I really liked those.”

One boy said, “My librarian at school gave me that book about Ralph. The mouse? And then I found the Ramona books next to it on the shelf. And I really liked those.”

While I was taking in this response, absorbing what insight it might offer about assumptions, shelf order, and readers’ advisory, another girl brought me back to the present in a pitying tone:

“There was the movie, you know…” [2010’s Ramona and Beezus]

Right.

“Well,” I told them, “Beverly Cleary, who wrote the Ramona books, is celebrating a big birthday this year. She’s going to be one hundred years old…”

Gasp.

“Is she still alive?!”

“Is she coming here!?!”

“Let’s have her come here!!!”

“She is very much alive! But she wrote the Ramona books a long time ago. I read them when I was your age. The first one was written in 1955…[dramatic pause] Do they seem old-fashioned to you?”

Silence and thinking and looking around at each other.

“Some things a little bit. But not the way she fights with her sister!” declared a boy, which inspired a lot of vocal solidarity from around the table.

“Ramona is funny,” smiled another girl.

“Ramona is funny,” smiled another girl.

The mom who had read the books aloud to her daughter interjected an important point: “Some of the details in the first ones are a bit dated now. But they were written over such a long period of time…The last ones weren’t written all that long ago.”

Though Ramona only ages about six years in those eight books, the series itself spans forty-four years, from 1955 to 1999.

“Are we going to read Ramona next?” another boy wanted to know.

Inspired by their enthusiasm, I re-read the series myself. I have often revisited my old friend Ramona, whom I first met when I was in second grade, thanks to my own school librarian. The Quimby family taught me, an only child like Beverly Cleary, the nuances of a sibling dynamic better than a graduate-level psychology class could. Even now, I continue to make new connections and discoveries when reading these books.

Through all these years, nothing much has changed about being little and not having much control. The issues Cleary addresses in her books are ones our children still deal with, and they can be scary and isolating. What if my family is keeping a secret from me? What if my family doesn’t have enough money? What if my dad loses his job? What if I don’t like my sibling? What if there is a new baby coming? What if my parents get divorced? What if my teacher doesn’t understand me? What if I do something cruel? What if someone does something cruel to me?

Beth McIntyre, former Cambridge Public librarian (now Madison County Poblic librarian, Wisconsin), shows off her Ramona Quimby Q tattoo. Photo: Beth McIntyre.

The plot points and details are honest and not sanitized for anyone’s benefit. Be it 1975 or 2016, sometimes a kid really does need to blow off steam by singing “99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall” in its entirety as loudly as possible for all the neighbors to hear.

When Cleary’s characters experience fear, love, jealousy, boredom, anger, or worry, we all recognize those emotions. She brings them sharply into focus. They are emotions we have felt and will keep feeling, but maybe up until that moment, we thought we were the only ones. What a relief to share the burden. What a relief to find that even if things don’t turn out as planned, there is hope and probably a really good laugh to be had as well.

Why, thought Beezus, Aunt Beatrice used to be every bit as awful as Ramona. And yet look how nice she is now. Beezus could scarcely believe it. And now Mother and Aunt Beatrice, who had quarreled when they were girls, loved each other and thought the things they had done were funny! They actually laughed about it. Well, maybe when she was grown-up she would think it was funny that Ramona had put eggshells in one birthday cake and baked her rubber doll with another. Maybe she wouldn’t think Ramona was so exasperating, after all. Maybe that was just the way things were with sisters. (Beezus and Ramona)

Maybe, Beezus. Maybe.

Happy birthday, Beverly Cleary! We love you in Cambridge, Massachusetts. You have brought us so much laughter and confidence — as we have grown both as readers and as humans. You have made our many troubles easier to bear. You have connected us, generation to generation, family to family, by showing us what we have in common as people.

We hope you have the best birthday cake — free of eggshells and baked-in rubber dolls.

We all want autograph albums.

We want you to sign every page.

From the March/April 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. Happy 100th Birthday, Beverly Cleary! For more, click the tag Beverly Cleary at 100.

The post Ramona in the 21st-Century Library appeared first on The Horn Book.

One-of-a-kind British writer Peter Dickinson died in December at age eighty-eight. His work cannot be easily categorized: a prolific author, he wrote everything from adult detective novels to speculative YA science fiction to heart-stopping adventures to intriguing almost-fantasies. The protagonists in his work for children range from an American-missionary boy who finds himself trekking through Tibet during the Boxer Rebellion (Tulku) to a blind teen who finds himself swept up in a plot by environmental terrorists to hijack a North Sea oil rig (Annerton Pit) to a human girl who finds herself transplanted into a chimp’s body (Eva). His books were wholly original, brimming with ideas, often concerned with the nature of religion and/or what makes us human — and also unfailingly compelling and masterfully plotted. Yet he did not consider himself an artist, but a craftsman: “I have a function, like the village cobbler, and that is to tell stories.”

One-of-a-kind British writer Peter Dickinson died in December at age eighty-eight. His work cannot be easily categorized: a prolific author, he wrote everything from adult detective novels to speculative YA science fiction to heart-stopping adventures to intriguing almost-fantasies. The protagonists in his work for children range from an American-missionary boy who finds himself trekking through Tibet during the Boxer Rebellion (Tulku) to a blind teen who finds himself swept up in a plot by environmental terrorists to hijack a North Sea oil rig (Annerton Pit) to a human girl who finds herself transplanted into a chimp’s body (Eva). His books were wholly original, brimming with ideas, often concerned with the nature of religion and/or what makes us human — and also unfailingly compelling and masterfully plotted. Yet he did not consider himself an artist, but a craftsman: “I have a function, like the village cobbler, and that is to tell stories.”

Peter Dickinson’s 1993 Horn Book Magazine article “Masks“

Horn Book Magazine reviews of select titles by Peter Dickinson

“A Defense of Rubbish” by Peter Dickinson

The post Peter Dickinson, 1927-2015 appeared first on The Horn Book.

To make a Tequila Mockingbird, chill your martini glass and cocktail shaker in the freezer. After half an hour, remove the shaker, throw in a handful of ice, one and a half ounces of tequila, three quarters of an ounce creme de menthe, and the juice of one lime. Shake vigorously, pour into a chilled glass, and garnish with a lime. Best enjoyed on an evening when it’s warm enough to linger on a veranda, but not so hot that ladies are reduced, as Alabama-born author Harper Lee so memorably described, to “soft teacakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.”

To make a Tequila Mockingbird, chill your martini glass and cocktail shaker in the freezer. After half an hour, remove the shaker, throw in a handful of ice, one and a half ounces of tequila, three quarters of an ounce creme de menthe, and the juice of one lime. Shake vigorously, pour into a chilled glass, and garnish with a lime. Best enjoyed on an evening when it’s warm enough to linger on a veranda, but not so hot that ladies are reduced, as Alabama-born author Harper Lee so memorably described, to “soft teacakes with frostings of sweat and sweet talcum.”

To Kill a Mockingbird has inspired odder and greater things than the combination of creme de menthe and tequila. July 11, 2010, marked the fiftieth anniversary of Lee’s venerated, controversial, and unavoidable book. Celebrations were everywhere. Special readings and panel discussions took place in locales from Vermont to Alabama to Washington, the 1962 movie starring Gregory Peck in his Oscar-winning role was shown in numerous theaters and libraries across the country, and a bookstore in Santa Cruz, California, hosted a reenactment of the famous courtroom scene. Not even the satirical paper The Onion could resist Mockingbird mania with this spoof headline: “Senate Unable to Get Enough Republican Votes to Honor ‘To Kill a Mockingbird.'” Not everyone, however, was extolling Mockingbird‘s praises. In a June 24, 2010, Wall Street Journal article, “What ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ Isn’t,” journalist Allen Barra kicked Harper Lee out of the canon of great Southern writers. He called Atticus a “repository of cracker-barrel epigrams” and the book as a whole “a sugar-coated myth of Alabama’s past that millions have come to accept.” Though Barra argued that Mockingbird’s “bloodless liberal humanism is sadly dated,” last summer’s celebrations showed how great a hold it has on readers’ memories and their hearts.

Now that the anniversary hoopla has subsided, will this classic that was never meant to be a blockbuster–or a children’s book, for that matter–be quietly retired? No. If anything, the fiftieth anniversary reminds us how this book has become so much more than a book. It has generated not just a cocktail but song lyrics, band names, and children’s and dogs’ names, and myriad young adult books have been inspired by its power. Mockingbird has become a part of the public subconscious, a literary and a cultural touchstone.

Now that the anniversary hoopla has subsided, will this classic that was never meant to be a blockbuster–or a children’s book, for that matter–be quietly retired? No. If anything, the fiftieth anniversary reminds us how this book has become so much more than a book. It has generated not just a cocktail but song lyrics, band names, and children’s and dogs’ names, and myriad young adult books have been inspired by its power. Mockingbird has become a part of the public subconscious, a literary and a cultural touchstone.

To attend high school in the United States is to be required to read Mockingbird. First published in 1960, this novel shocked its debut author and her publisher when it won the Pulitzer Prize and became a best seller. Since then, Mockingbird has sold nearly one million copies a year, and for the past five years has been the second-best-selling backlist title in the country. (Eat your hearts out, Stephenie Meyer and J. K. Rowling.) But how did Mockingbird become a book for youth? Is it because the narrator, Scout, is a young tomboy? Or is it because the novel is both a bildungsroman and a suspenseful courtroom drama? Or was Mockingbird eventually labeled a children’s book simply because Flannery O’Connor mused, “It’s interesting that all the folks that are buying it don’t know they are reading a children’s book”? Given Mockingbird‘s cultural permeation and multigenerational readership, it appears to be a true example of a “book for all ages.”

Mockingbird‘s hold on grown-up minds is certainly evident in the many pop-culture allusions, both obvious and subtle, to Lee’s only book. Celebrity magazine readers are probably aware that Demi Moore and Bruce Willis named their daughter Scout after Lee’s precocious protagonist. Watchers of the television show Gilmore Girls probably caught the literary reference when Rory says that “every town needs as many Boo Radleys as they can get.” And Simpsons viewers young and old undoubtedly laughed when Homer complained about reading: “Books are useless! I only ever read one book, To Kill a Mockingbird, and it gave me absolutely no insight on how to kill mockingbirds! Sure it taught me not to judge a man by the color of his skin… but what good does that do me?”

Mockingbird has also entered the twitterverse via Twitterature: The World’s Greatest Books in Twenty Tweets or Less by Alexander Aciman and Emmett Rensin. Aciman and Rensin have Scout narrate as @BooScout in a voice condensed to short, often snarky observations. Here’s @BooScout’s response to Atticus’s advice that to understand a person you must put yourself in his shoes: “Why does Dad say such LAME shit? I don’t want to walk a mile in ANYONE else’s shoes. Toe jam, nail fungus, athlete’s foot anybody? Gosh.” High literature Twitterature is not, but anyone who has studied Mockingbird with a long-winded lecturer will appreciate @BooScout’s humor and brevity: “Went to the trial. Tom seems innocent. Also, it occurs that our town is full of racists. Perhaps only the eyes of a child can see the truth.”

Beyond pop culture, Mockingbird has long provided the legal arena with both inspiration and fodder for discussion. Atticus’s courtroom defense of Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping a white woman, is the subject of law school classes and law review articles. Would Atticus’s argument that Tom physically couldn’t have harmed Mayella Ewell hold water in a contemporary courtroom? Does Atticus deserve our veneration? In his August 10, 2009, New Yorker article “The Courthouse Ring,” Malcolm Gladwell takes Atticus to task for his legal performance. Gladwell argues that instead of challenging the racist status quo, Atticus simply encourages jurors “to swap one of their prejudices for another.” He also finds Atticus’s decision to have Scout lie about what actually happened the night Bob Ewell attacked her and her brother Jem problematic: “Understand what? That her father and the Sheriff have decided to obstruct justice in the name of saving their beloved neighbor the burden of angel-food cake?” Whether Atticus is a brilliant attorney or a courtroom wimp, the fact that Gladwell and legal scholars are even debating his aptitude with the seriousness they might read Supreme Court decisions speaks of Mockingbird‘s clout.

Like its impact on pop culture, Mockingbird‘s presence in literature is a combination of overt tributes and almost subconscious allusions. In Scout, Atticus & Boo: A Celebration of Fifty Years of To Kill a Mockingbird (2010), author Mary McDonagh Murphy interviews writers, journalists, and artists from Oprah Winfrey to Tom Brokaw about how Mockingbird affected their lives. Her interviews with authors including James Patterson, Adriana Trigiani, and Lizzie Skurnick exemplify how this classic, though often read in childhood, can have a lasting hold on writers. Patterson loved it because he identified with Jem and “the suspense was unusual in terms of books that I had read at that point, books that … had really powerful drama which really did hook you. Obviously I try to do [that] with my books.” Skurnick, author of Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading, recalls Scout being more fascinating than the “grand themes of justice” in the second half of the book. Everyone interviewed, regardless of vocation, has a story about how Mockingbird touched him or her in a memorable way.

Like its impact on pop culture, Mockingbird‘s presence in literature is a combination of overt tributes and almost subconscious allusions. In Scout, Atticus & Boo: A Celebration of Fifty Years of To Kill a Mockingbird (2010), author Mary McDonagh Murphy interviews writers, journalists, and artists from Oprah Winfrey to Tom Brokaw about how Mockingbird affected their lives. Her interviews with authors including James Patterson, Adriana Trigiani, and Lizzie Skurnick exemplify how this classic, though often read in childhood, can have a lasting hold on writers. Patterson loved it because he identified with Jem and “the suspense was unusual in terms of books that I had read at that point, books that … had really powerful drama which really did hook you. Obviously I try to do [that] with my books.” Skurnick, author of Shelf Discovery: The Teen Classics We Never Stopped Reading, recalls Scout being more fascinating than the “grand themes of justice” in the second half of the book. Everyone interviewed, regardless of vocation, has a story about how Mockingbird touched him or her in a memorable way.

Young adult books such as Jan Marino’s 1997 novel Searching for Atticus and Loretta Ellsworth’s 2007 In Search of Mockingbird are unabashed love letters to Mockingbird and maybe even Harper Lee herself. Both books feature teenage girls who set out on quests of self-discovery with Mockingbird as their inspiration. In Atticus, Tessa Ramsey tries to reconnect with her surgeon father who has returned from the Vietnam War, while in In Search of Mockingbird Erin runs away from Minnesota to find the reclusive author of her favorite book. Also Known as Harper (2009) by Ann Haywood Leal, National Book Award winner Mockingbird (2010) by Kathryn Erskine, and The Mockingbirds (2010) by Daisy Whitney pay homage to Harper Lee, with varying degrees of genuflection and success.The impact of To Kill a Mockingbird on a text is not always apparent from the title. Sometimes the novel is used in a story as a character litmus test: if a protagonist is reading it and loves it, readers know he or she is a good person–extra points if the copy is dog-eared and not required homework reading. In a similar vein, though Atticus might not be named in a text, it is hard not to think of him in any middle-grade or young adult novel with a courtroom setting. (Monster by Walter Dean Myers and John Grisham’s foray into children’s books Theodore Boone: Kid Lawyer come to mind.)

unabashed love letters to Mockingbird and maybe even Harper Lee herself. Both books feature teenage girls who set out on quests of self-discovery with Mockingbird as their inspiration. In Atticus, Tessa Ramsey tries to reconnect with her surgeon father who has returned from the Vietnam War, while in In Search of Mockingbird Erin runs away from Minnesota to find the reclusive author of her favorite book. Also Known as Harper (2009) by Ann Haywood Leal, National Book Award winner Mockingbird (2010) by Kathryn Erskine, and The Mockingbirds (2010) by Daisy Whitney pay homage to Harper Lee, with varying degrees of genuflection and success.The impact of To Kill a Mockingbird on a text is not always apparent from the title. Sometimes the novel is used in a story as a character litmus test: if a protagonist is reading it and loves it, readers know he or she is a good person–extra points if the copy is dog-eared and not required homework reading. In a similar vein, though Atticus might not be named in a text, it is hard not to think of him in any middle-grade or young adult novel with a courtroom setting. (Monster by Walter Dean Myers and John Grisham’s foray into children’s books Theodore Boone: Kid Lawyer come to mind.)

It’s even harder, if not impossible, to see words closely resembling mockingbird on a page and not think of Lee’s work. Suzanne Collins, whether intentionally or not, recalls To Kill a Mockingbird with her mockingjay creature in the Hunger Games trilogy. In the final book of the series, Mockingjay, Collins’s protagonist Katniss describes a mockingjay, a combination of a (fictional) jabberjay and a mockingbird, as “the symbol of the revolution” and goes on to explain why she must represent the mockingjay herself and “become the actual leader, the face, the voice, the embodiment of the revolution.” Katniss’s understanding of the emblematic importance of the mockingjay brings to mind Scout’s discussion with Miss Maudie Atkinson about why she should never shoot a mockingbird: “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

It’s even harder, if not impossible, to see words closely resembling mockingbird on a page and not think of Lee’s work. Suzanne Collins, whether intentionally or not, recalls To Kill a Mockingbird with her mockingjay creature in the Hunger Games trilogy. In the final book of the series, Mockingjay, Collins’s protagonist Katniss describes a mockingjay, a combination of a (fictional) jabberjay and a mockingbird, as “the symbol of the revolution” and goes on to explain why she must represent the mockingjay herself and “become the actual leader, the face, the voice, the embodiment of the revolution.” Katniss’s understanding of the emblematic importance of the mockingjay brings to mind Scout’s discussion with Miss Maudie Atkinson about why she should never shoot a mockingbird: “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corncribs, they don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

To Kill a Mockingbird is perhaps our foremost example of the private reading experience writ larger by its communal–and now multigenerational–replication. Fans and the indifferent alike can remember when and where they were when they read the book, voluntarily or not, for the first time. Recollection of that memory of reading, perhaps even more than the book itself, is the reason To Kill a Mockingbird has become an enduring metaphor for justice, goodness, and the bittersweetness of growing up.

From the May/June 2011 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. See also “From the Guide: More Mockingbird.”

The post A Second Look: The Long Life of a Mockingbird appeared first on The Horn Book.

In our January/February 2016 issue, reviewer Dean Schneider talked with author Audrey Vernick about her clear love of America’s favorite pastime. Read the full review of The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton here.

In our January/February 2016 issue, reviewer Dean Schneider talked with author Audrey Vernick about her clear love of America’s favorite pastime. Read the full review of The Kid from Diamond Street: The Extraordinary Story of Baseball Legend Edith Houghton here.

Dean Schneider: You’ve written a few books about baseball. Have you always been a fan? Or did you become one after you started writing about the sport?

Audrey Vernick: One of my favorite things about being a grownup is no one can make me write about explorers. I write about baseball because I truly love it and have for decades. While I am a devoted fan of a team I’ll not mention by name in a Boston-based publication, I also love the game’s rich, textured history and the individual stories folded within it.

From the January/February 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The post Audrey Vernick on The Kid from Diamond Street appeared first on The Horn Book.

In our January/February 2016 issue, reviewer Sarah Ellis asked illustrator Antoinette Portis about that pesky (playful?) wind in The Red Hat. Read the full review of The Red Hat here.

In our January/February 2016 issue, reviewer Sarah Ellis asked illustrator Antoinette Portis about that pesky (playful?) wind in The Red Hat. Read the full review of The Red Hat here.

Sarah Ellis: The “bad guy” here is the wind, but in your swirly, spiral line the wind comes across as more playful than malevolent. Was it hard to figure out how to make a 3-D character out of a no-D antagonist?

Antoinette Portis: Instead of personifying the wind as one of the puffy-cheeked Greek gods you see on antique maps or as an evil villain, I imagined it as an externalization of Billy’s resistance to venturing out into the world. When he’s impelled to risk forging a relationship, all his fears don’t suddenly evaporate. They manifest themselves as the wind, trying to drive him back to the safety and isolation of his tower.

From the January/February 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

The post Antoinette Portis on The Red Hat appeared first on The Horn Book.

By:

Roger Sutton,

on 1/12/2016

Blog:

Read Roger - The Horn Book editor's rants and raves

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Featured,

primary,

preschool,

barbara mcclintock,

notes0116,

Interviews,

dance,

Picture Books,

Authors & Illustrators,

Add a tag

Each of author/illustrator Barbara McClintock’s picture books provides a glimpse into a jewel-box of a world, from bustling early-twentieth-century Paris (Adèle & Simon; Farrar, 4–7 years) to a cozy 1970s mouse-house (Where’s Mommy?, written by Beverly Donofrio; Schwartz & Wade, 4–7 years). Her latest, Emma and Julia Love Ballet (Scholastic, 4–7 years), does the same for the vibrant world of ballet, giving readers a look at the daily routines of two dancers: one a student just starting out, the other a professional in her prime. A dancer myself, I jumped at the chance to talk to Barbara about how she translates movement to the page.

Each of author/illustrator Barbara McClintock’s picture books provides a glimpse into a jewel-box of a world, from bustling early-twentieth-century Paris (Adèle & Simon; Farrar, 4–7 years) to a cozy 1970s mouse-house (Where’s Mommy?, written by Beverly Donofrio; Schwartz & Wade, 4–7 years). Her latest, Emma and Julia Love Ballet (Scholastic, 4–7 years), does the same for the vibrant world of ballet, giving readers a look at the daily routines of two dancers: one a student just starting out, the other a professional in her prime. A dancer myself, I jumped at the chance to talk to Barbara about how she translates movement to the page.

1. How did you decide on this day-in-the-life, compare-and-contrast format for showcasing a dancer’s reality?

BM: I blame two of my favorite books for putting the idea in my head: The Borrowers by Mary Norton and The Philharmonic Gets Dressed by Karla Kuskin, illustrated by Marc Simont. The parallel world of The Borrowers fascinated me as a child. And I fell in love — hard! — with the behind-the-scenes showering, sock-pulling-on, hair-combing, and beard-trimming preparations of orchestral musicians before their evening performance in The Philharmonic Gets Dressed.

My older sister Kathleen lived, breathed, ate, and slept ballet when she was little, and I’d wanted to make a book honoring her for a long time. She took me to my first professional dance performance, which proved to have a profound influence on my creative life. Her passion for dance inspired me to believe in myself as an artist.

2. Many of your books are set in bygone eras, with richly evoked historical settings full of texture and detail. How does your process differ when you’re portraying a contemporary setting rather than recreating a historical one?

BM: I tend to use slightly bolder, brushlike line work, little or no crosshatching, and brighter colors when working with a contemporary setting. Modern surfaces are shinier, glossier, brighter, harder. Metal and glass predominate. I find it’s easier to depict those hard, shiny surfaces with gradated watercolor washes. Textural ink crosshatching seems appropriate for older stone, wood, and plaster surfaces.

Modern forms call for fluid lines, less encumbered by lots of line work. There’s detail in contemporary buildings and clothing, but forms are more nuanced, freer, with open patterns and simplified shapes compared to historical structures and fashion.

Shapes of contemporary things that move — cars, airplanes, trains — are smooth and somewhat egg-shaped, reflecting aerodynamic design considerations. Carriages, carts, and buggies are boxy, with lots of angles, which makes for different compositional elements in pictures.

3. The format of Emma and Julia Love Ballet is almost graphic novel–like, with the illustrations changing sizes and shapes to accelerate the pacing. How do you know what size illustration to use when?

3. The format of Emma and Julia Love Ballet is almost graphic novel–like, with the illustrations changing sizes and shapes to accelerate the pacing. How do you know what size illustration to use when?

BM: The size and shape of the illustrations is all about creating a sense of time, movement, emotion, and place.

Vignettes isolate characters to form a sense of intimacy between the reader and the character, like a spotlighted actor on stage. There can be a powerful emotional component to vignettes. Toward the end of the book as Emma prepares to go to the ballet performance, we see her in her fancy coat, with no background, nothing else in the image. Her facial expression alone tells us this is an important time for her. Anything else in the scene would impede the immediacy of her excitement.

Vignettes can also signify rapid movement and the passage of time. Several small vignettes on a page require only short amounts of time to look at. This visual device works well to depict Emma and Julia stretching, jumping, and spinning. Viewing several small images in quick succession can be like looking at a flip-book that gives the impression of fast, fluid motion.

Broad, dramatic scenes create a sense of mood and establish place; and fuller, detailed pictures slow the reader down at significant moments by creating an environment that invites investigation. That lingering pause can give majesty to a scene or narrative concept.

At the very end of the book, I wanted to go back to a vignette approach. We see Emma and Julia connected by their shared love of ballet. I wanted Emma and Julia to dominate and fill up the entire page with no external stuff to clutter up their emotional connection. This is their story, and they tell us absolutely and directly how they feel about ballet and each other.

4. You observed the Connecticut Concert Ballet as models for the illustrations, and took some ballet classes yourself for research. How did your perspective — or your illustrations — change after these experiences?

BM: I have a much better idea of just how hard a plié in fifth position is on your inner thighs!

Watching people in motion is a much different experience than simply studying photographs. Semi-realistic drawing has so much to do with gesture, and the best way to understand how an arm or leg really moves through space is to observe someone in the act of moving. As I draw the sweep of an arm, I get inside that motion. I’m not entirely sure how to express this, but I feel the movement in my head as a physical motion and visualize where that arm is going, then translate that motion as well as I can in a two-dimensional way on paper.

Ballet has its own regimented structure of movement. I just dipped into the surface of knowledge of ballet training, but hopefully enough to give some authenticity to the way the dancers in my book move.

Barbara in the ballet studio

5. The book is dedicated in part to the wonderful Judith Jamison, dancer and Artistic Director Emerita of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Is there a particular role of Ms. Jamison’s that resonates most with you?

BM: In the early 1970s my sister took me to see the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Minneapolis. Judith Jamison was the featured soloist. This was the first professional dance performance I’d ever seen. I had no idea what to expect, and was almost afraid to go. Any hesitation vanished the moment Judith stepped on stage. She dominated space and time, creating vivid shapes and patterns.

Judith performed Cry, a sixteen-minute solo homage to black women, choreographed by Alvin Ailey for his mother with Judith in mind. Judith expressed grief, depression, loss, redemption, and joy as eloquently as any novelist. I loved dance from that evening on.

Judith’s presence, authority, and grace inspired me in my work. I admired her, and looked up to Judith as a role model — a woman who was in command of her talent and a force almost bigger than life.

From the January 2016 issue of Notes from the Horn Book.

The post Five questions for Barbara McClintock appeared first on The Horn Book.

Thank you so much. Thank you to the judges — Barbara, Jessica, and Maeve. Thank you for placing me in the company of two of my very favorite picture book creators, Jon Agee and Oliver Jeffers.

Thank you so much. Thank you to the judges — Barbara, Jessica, and Maeve. Thank you for placing me in the company of two of my very favorite picture book creators, Jon Agee and Oliver Jeffers.

By giving this award to The Farmer and the Clown, you have helped move the needle a little bit on issues of cultural diversity. Clowns have been marginalized for far too long. Hated even.

Farmers, too, for that matter.

If this award can help us embrace a world in which farmers and clowns can co-exist without everyone getting all riled up, then that is just incredible.

* * *

I have always loved the time between when I finish a book and when it gets the first review. I can relax into knowing that I made a book and I gave it everything I had. I get to clean my studio with a sense of accomplishment. The book exists outside of me, but it’s not yet public.

Then the reviews arrive, and they usher in a whole new phase. I learn a lot about what exactly I made from the reviews. Maybe the takeaway is different than what I thought it would be. Maybe a larger theme had escaped me. Maybe the dogs I drew actually look like cats.

Then the book goes out and lives its life. Booksellers, teachers, librarians, and parents find it — hopefully. Children, the intended audience, hopefully do, too. This is the point, after all, and it is always profound.

After going through this process with twenty-seven books, I’ve learned to manage the highs and lows pretty well. But with The Farmer and the Clown, I found there was a whole new phase to navigate. The book became fodder for some very bizarre discussions on social media. This wasn’t the usual zaniness of Amazon reviews gone off the rails, but respected names in our field giving voice to unsubstantiated opinions of others. No one took ownership.

A lot of what was said I won’t dignify. It was beneath us.

But some things that were said are important to talk about because they’re issues at the heart of our collective work. One is the opinion, often delivered as fact, that wordless books are harder for illustrators to do than books with words. I’m not sure where this idea began, but it seems to have taken root — so much so that discussions and reviews about wordless books often begin with the assumption that it was an extraordinary leap for the illustrator.

For me, finding the right balance between the words and pictures in Liz Garton Scanlon’s evocative — and not at all narrative — All the World text was every bit as challenging as this wordless book I made. After months of working on All the World, I had to start all over again and go all the way back to thumbnail sketches. Turned out that my picture-story was strong-arming the text by forcing narrative connections between the characters. I had eclipsed the larger theme of expansiveness.

Illustrating the folk song “Hush Little Baby” was challenging, too. I wanted the picture-story to have the same rollicking spirit as Pete Seeger’s banjo in his rendition of the lullaby, so I visualized the pictures as galloping alongside the words. Sometimes they were in tandem, sometimes they crossed paths, sometimes they veered far away from each other. Making sure words and pictures don’t stomp all over each other is maybe even harder than concentrating on one or the other by itself.

I also read that because The Farmer and the Clown was wordless, I ceded a greater degree of control over the narrative to the reader. I disagree. I didn’t surrender control. That gives the visual narrative no respect. And it assumes the words deliver the clearer story. But words can be equally misinterpreted.

For instance, my ex-husband’s Midwestern family uses the word squeeze as a euphemism for going to the bathroom. Imagine what he thought was happening in the story when he heard these words read to him as a child: “Peter, who was very naughty, ran straight away to Mr. McGregor’s garden, and squeezed under the gate!”

Anyone can bring their own crap to words or pictures. That’s something authors and illustrators have little control over.

But a picture-story has an advantage over a word-story, and that is that children are experts at reading pictures. Because of this, a visual narrative actually surrenders less control over the narrative to the child. Children bring a clear-eyed, intense, lingering, unsentimental, and sophisticated focus to reading pictures. They can read them in a literal, metaphorical, or ironic sense, depending on what’s called for, and they can tell what’s called for. They are a highly discerning audience to draw pictures for. Because children are seeing clearly what meets their eye, they don’t assume (the way grownups might) that there is something beyond what they are seeing.

Contrast that with how most grownups experience the pictures. If they give even a passing glance to the pictures as something more than decoration, they often tend to read into them. Insert their own story or experience. Presume stuff that isn’t there. Gloss over what is.

Of course I’m not saying all grownups do this. Although I do think that when words and pictures are competing for the grownups’ attention, words tend to win. But children focus on the pictures because they can’t read words yet or can’t read them easily. And so they study those pictures for meaning in a way that adults don’t have to anymore.

* * *

Before I settle into my studio in the morning, I often hike in the mountains above Pasadena with my dog. There are rivers to cross (or there were before the drought). The way a child reads pictures in a picture book is the same way you get across the water. Rock to rock. If you are a child who can’t yet read, your eyes will land on the pictures the way your foot lands on a rock. One picture to the next to the next.

If illustrators don’t provide enough landings, if we don’t plan them out carefully, we will strand that child in the middle of the river. But if we do it well, we will bring the child all the way across. Some pictures are resting places; some are quick, light hops; some are tippy on purpose; some are functional bridges. Add the magical page-turn, the rhythm of the words, a lap or story circle, and we’ve got the picture book—a form that has stolen our hearts.

I have learned about this form from many teachers, beginning with The Horn Book Magazine. I’ve read (and saved) every issue since I graduated from Art Center College of Design in 1981. It’s been my master’s program. For thirty-four years. Thank god the tuition is reasonable — and a write-off.

My first editor, Linda Zuckerman, told me that my commercial illustration portfolio wasn’t narrative enough for children’s books. She explained this many times, in many ways, over many years. It took me so long to get it.

Allyn Johnston caught me up after Linda left the field and has hung in there with me the whole time since. Allyn’s intuition about picture books, how they must deliver emotion and crack the reader open in one way or another, has been the guiding principle of the many books we’ve made together.

My agent, Steve Malk, with his bookseller background and sharp eye for craft, has represented me for fifteen years. He was twenty-three when I first met him and already had much to teach me. I am really proud to be in the group of writers and illustrators he works with.

* * *

The idea for The Farmer and the Clown came to me around the same time that my marriage of thirty-one years was coming apart.

The book is about two characters who look a certain way on the outside but are actually a whole other way on the inside. As the idea developed and the book took form, my personal life went through a complete upheaval. Many of us will fall off our train at some point in our lives, and I fell off mine during the time I worked on this book. Hard landing, unforgiving landscape. One day I was tough as the farmer. The next, lost as the clown. Some days I benefited from the kindness of strangers so surprising in their tenderness. And every single day, in ways large and small, I was enveloped by the open arms of my family, a crazy clown troupe if there ever was one.

But while I was working on the book, I wasn’t making these connections at all. In fact, Allyn sent a text to me one day as I was putting the finishing touches on the last painting. It said: “Home. You know where it is when you’re there. But sometimes you get a bit separated from home, and you may need a little help finding your way back.”

I couldn’t imagine what she was talking about. Was she lost? Was I? It took me a long time to figure out she was proposing Farmer and the Clown flap copy. I had no idea that was what the book was about.

Then, after I cleaned my studio, and after the reviews, and after the social media circus, I started to hear from readers.

I got an email that said:

I read it with my four-year-old daughter, and the phone rang with an important call that I’d been expecting, so I handed the open book to her and told her I’d be right back. While I was gone, she finished reading it. When I hung up the phone, I turned around and there she was. “Mommy. The clown’s family came back.” “Is that so? And he went with them then?” “Yes, but first he gave the farmer a giant hug. A GIANT one. And then the farmer whispered ‘I love you’ into his ear. And you know the funniest thing? The farmer doesn’t even know that a monkey is following him home right this minute.”

And another:

I read the book to my three-year-old granddaughter. When we were finished reading, I asked her what she was thinking. “I’m thinking that the clown and the farmer will always remember each other.” I agreed that they would because of all the great moments they’d shared. Her comment started a conversation about the people in our lives who’ve left us something, tangible or intangible. My granddaughter has already lost several people that she loves and we had a chance to remember the things they’ve left behind so that we’re able to remember them.

This is truly an upside of online communication — people have shared many touching stories about The Farmer and the Clown with me. About how children, even as young as two, suddenly had a way to talk about love and loss and grief and saying goodbye and keeping remembrances of people they were missing who had meant a lot to them.

This is why I continue to have the utmost respect for children’s ability to read pictures in a way that far surpasses our own. I remember very well the feeling I had as a child that the illustrations were speaking directly to me in a secret, private language. No grownup needed to explain it. No grownup needed to interpret it. It was simply there for me, for the taking.

Thank you for honoring this book with this award.

From the January/February 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. For more on the 2015 Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards, click on the tag BGHB15.

The post The Farmer and the Clown: Marla Frazee’s 2015 BGBH PB Award Speech appeared first on The Horn Book.

It was with surprise and gratitude that I heard about receiving a Boston Globe–Horn Book honor award. This book was a risk, in that it’s an alphabet book which is a bit over the heads of the people who are most likely to be reading an alphabet book. Instead it’s a book that’s just about the joy of using language and wordplay, with some of the randomness of the workings of my brain thrown in. (It’s also a book for those too embarrassed and too far gone to admit they never learned their ABCs…I know who you are!)

It was with surprise and gratitude that I heard about receiving a Boston Globe–Horn Book honor award. This book was a risk, in that it’s an alphabet book which is a bit over the heads of the people who are most likely to be reading an alphabet book. Instead it’s a book that’s just about the joy of using language and wordplay, with some of the randomness of the workings of my brain thrown in. (It’s also a book for those too embarrassed and too far gone to admit they never learned their ABCs…I know who you are!)

It was a risk to publish a 112-page picture book that was mostly black and white, effectively a collection of short stories that are convoluted and weird…but a risk that was worth it. It is a book I am deeply proud of. Thank you to the judges and to all of the people who were prepared to go down this strange road with me. Without you, we may never have had an Owl and Octopus Problem Solving Agency, a parsnip with identity issues, or the invention of a jelly door—and I for one believe the world is a better place with them in it. Somewhat…

From the January/February 2016 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. For more on the 2015 Boston Globe-Horn Book Awards, click on the tag BGHB15.

The post Once Upon an Alphabet: Oliver Jeffers’s 2015 BGHB PB Honor Speech appeared first on The Horn Book.

Thank you to The Horn Book and the Boston Globe. And to Lauri Hornik and Lily Malcom, my wonderful publisher and art director. And congratulations to Marla and Oliver. (Great choices, judges.)

Thank you to The Horn Book and the Boston Globe. And to Lauri Hornik and Lily Malcom, my wonderful publisher and art director. And congratulations to Marla and Oliver. (Great choices, judges.)

A few words about It’s Only Stanley:

This is a love story. There’s a lot of love in this book — blind, delusional, human love along with deep, primordial, canine passion.

It’s the story of the Wimbledon family — dog-owners — who, like many of us, treat their beloved Stanley as if he’s a human being. I’m guilty of this. I have a little, fluffy dog, and it rarely occurs to me that she’s actually descended from a wolf — until I try and take away her bully stick.