By David Seed

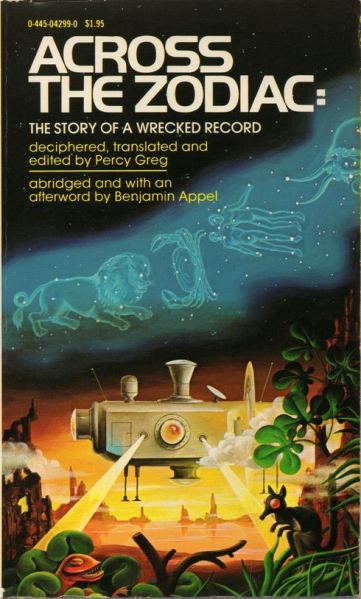

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the red planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was one of the strongest advocates of the idea in his 1908 book Mars as the Abode of Life and in other pieces, some of which were read by the young H.G. Wells. Mars had the obvious attraction of opening up new sensational subjects. Greg’s astronaut modestly describes his story as the ‘most stupendous adventure’ in human history. It also resembled a colony.

Although there had been interest in Mars earlier, towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a sudden surge of novels describing travel to the red planet. One of the earliest was Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880) which set the pattern for early Mars fiction by framing its story as a manuscript found in a battered metal container. Greg obviously assumed that his readers would find the story incredible and sets up the discovery of the ‘record’, as he calls it, by a traveler to the USA to distance himself from the extraordinary events within the novel. The space traveler is an amateur scientist who has stumbled across a force in Nature he calls ‘apergy’ which conveniently makes it possible for him to travel to Mars in his spaceship. When he arrives there, he discovers that the planet is inhabited. Since then, the conviction that beings like ourselves live on Mars has constantly fed writings about the planet. The American astronomer Percival Lowell was one of the strongest advocates of the idea in his 1908 book Mars as the Abode of Life and in other pieces, some of which were read by the young H.G. Wells. Mars had the obvious attraction of opening up new sensational subjects. Greg’s astronaut modestly describes his story as the ‘most stupendous adventure’ in human history. It also resembled a colony.

It’s no coincidence that the surge of Mars fiction coincided with the peak of empire, so by this logic the red planet is sometimes imagined as a transposed other country. Gustavus W. Pope’s Journey to Mars (1894) describes the voyage of an American spacecraft to a utopian world of sophisticated civilization and technology. The Martians encountered by the travelers are immediately identified as allies and one of the climactic moments in the novel comes when they fly the American flag during a naval parade. The narrator is almost moved beyond words by the spectacle:

My eyes filled with tears of joy when I thought that, the banner of liberty which waves o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave, honoured in every nation and on every sea of Earth’s broad domain, should have been borne through the trackless realms of space, amid that shining galaxy of orbs that wheel around the sun, and UNFOLD ITS BROAD STRIPES AND BRIGHT STARS OVER ANOTHER WORLD!

Pope’s description is unusual in presenting the Martians as so similar to the travelers that they project hardly any sense of the alien and, even more important, seem quite happy for America to take the lead in the course of civilization.

The most famous Mars novel from the turn of the twentieth century, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), takes the British treatment of the Tasmanians as a notorious example of brutal imperialism and then simply reverses the terms. The invading Martians simply direct against the capital city of the British Empire the same crude logic of empire: we are technologically able to conquer you, so we will do so. What still gives an impressive force to Wells’ narrative is the journalistic care that he took to document the gradual collapse of England. Despite its army and navy, the state is helpless to resist the Martians and they are only defeated by the germs of Earth rather than by its technology.

The most famous Mars novel from the turn of the twentieth century, H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898), takes the British treatment of the Tasmanians as a notorious example of brutal imperialism and then simply reverses the terms. The invading Martians simply direct against the capital city of the British Empire the same crude logic of empire: we are technologically able to conquer you, so we will do so. What still gives an impressive force to Wells’ narrative is the journalistic care that he took to document the gradual collapse of England. Despite its army and navy, the state is helpless to resist the Martians and they are only defeated by the germs of Earth rather than by its technology.

This story of collapse did not please the American astronomer Garrett P. Serviss, who immediately wrote a sequel, Edison’s Conquest of Mars. Rather than waiting passively for the Martians to return, as Wells warns they might in his coda, Serviss describes an expedition to conquer them on their home planet. Two steps have to be taken before this can be done. First, the American inventor Edison discovers the secrets of the Martians’ technology and devises a ‘disintegrator’, which will destroy its targets utterly. Secondly, the nations of the world have to chip in to the expedition with large donations. Serviss describes an amazingly unanimous global cooperation: “The United States naturally took the lead, and their leadership was never for a moment questioned abroad.” Put this narrative against the background of the USA taking over former Spanish colonies like Cuba and the Philippines, and Serviss’s narrative can be read as an idealized fantasy of America’s emerging imperial role in the world. Of course no conquest would be worthwhile if it came too easily and Serviss’s Martians aren’t the octopus-like creatures described by Wells, but instead represent human qualities and characteristics taken to inhuman lengths.

Empire was only one way of imagining Mars. It also offered itself as a hypothetical location for utopian speculation. This is how it functions in the Australian Joseph Fraser’s Melbourne and Mars (1889), whose subtitle — The Mysterious Life on Two Planets — indicates the author’s method of comparison. Similarly, Unveiling a Parallel, by Two Women of the West (1893), written by the Americans Alice Ingenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant, describes two alternative societies visited by a traveler from Earth. All Mars fiction tends to take for granted the technology of flight and the vehicle in this novel is an ‘aeroplane’, one of the earliest uses of the term. When the narrator lands on Mars he has no difficulty at all in adjustment or with the language, quite simply because Mars is not treated as an alien place so much as a forum for social change.

The most surprising characteristic of early Mars writing is its sheer variety. Sometimes the planet is imagined as a potential colony, sometimes as an alternative society, or as place for adventure. One of the strangest versions of the planet was given in the American natural scientist Louis Pope Gratacap’s 1903 book, The Certainty of a Future Life on Mars. The narrator’s father is a scientist researching into electricity and astronomy with a strong commitment to spiritualism. After he dies, the narrator starts receiving telegraphic messages from his father describing Mars as an idealized spiritual haven for the dead. It is typical of the period for Gratacap to combine science with religion in narrative that resembles a novel. Before we dismiss the idea of telegraphy here, it is worth remembering that the electrical experimenter Nikola Tesla published articles around 1900 on exactly this possibility of communicating electronically with Mars and other planets.

All the main early works on Mars are available on the web or have been reprinted. They make up a fascinating body of material which helps to explain where our perceptions of the red planet come from.

David Seed is Professor in the School of English, University of Liverpool. He is the author of Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Oxford University Press’ annual Place of the Year competition, celebrating geographically interesting and inspiring places, coincides with its publication of Atlas of the World — the only atlas published annually — now in its 19th Edition. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price. Read previous blog posts in our Place of the Year series.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: War of the Worlds’ 1st edition cover.

The post The discovery of Mars in literature appeared first on OUPblog.