new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: empire, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 10 of 10

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: empire in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: PennyF,

on 6/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

war,

World,

world war I,

timeline,

month,

British,

Diplomacy,

Europe,

july,

wwi,

first world war,

1914,

empire,

infographic,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

UKpophistory,

Archduke Franz Ferdinand,

gordon martel,

july 1914,

the month that changed the world,

world war I centennial,

martel,

centennial’,

centenary’,

Add a tag

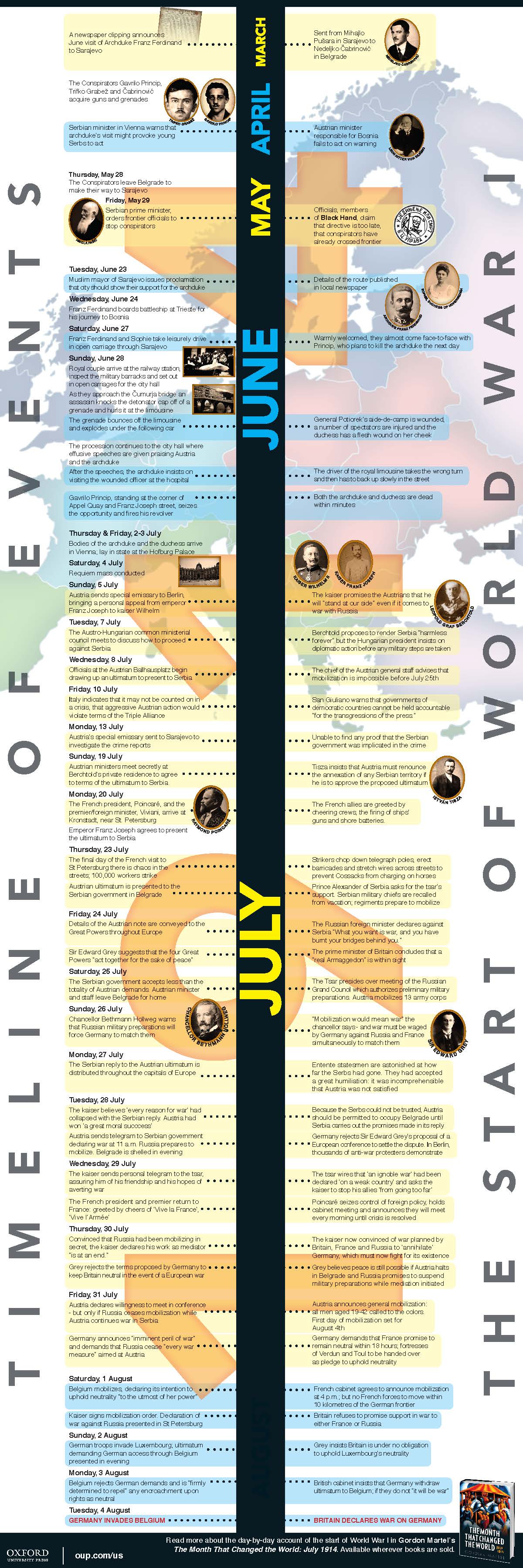

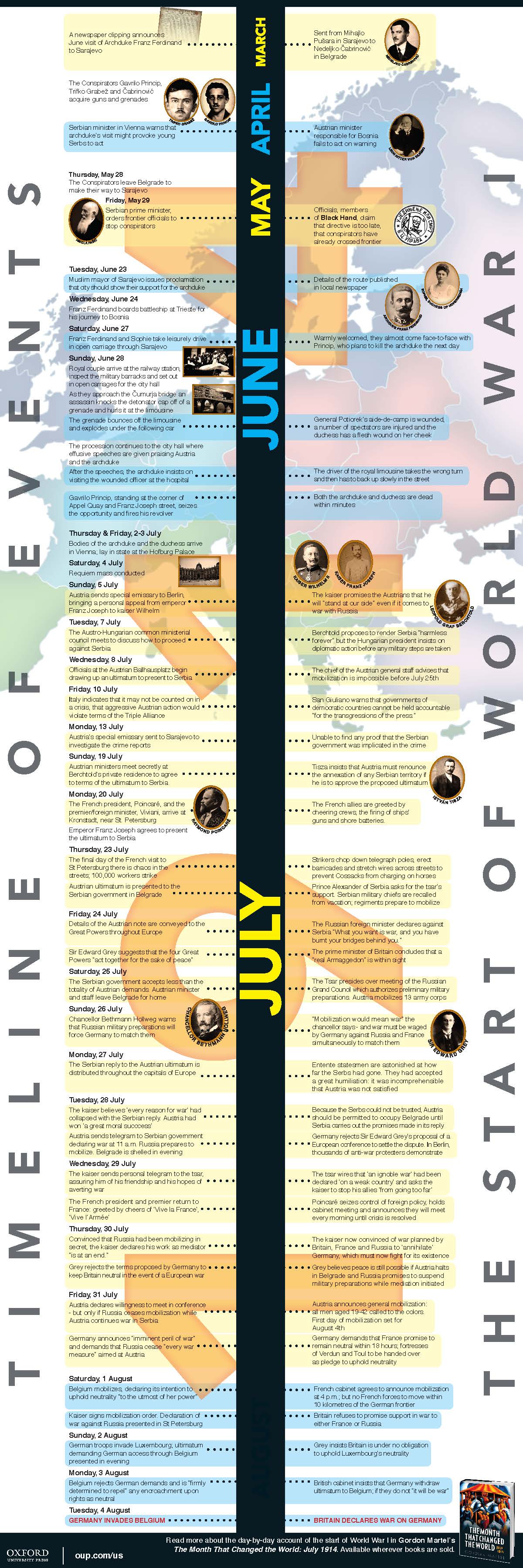

In honor of the centennial of World War I, we’re remembering the momentous period of history that forever changed the world as we know it. July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, will be blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War. Before we dive in, here’s a timeline that provides an expansive overview of the monumental dates to remember.

Download a jpeg or PDF of the timeline.

Gordon Martel is the author of The Month that Changed the World: July 1914. He is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-Chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also Joint Editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series.

Visit the US ‘World War I: Commemorating the Centennial’ page or UK ‘First World War Centenary’ page to discover specially commissioned contributions from our expert authors, free resources from our world-class products, book lists, and exclusive archival materials that provide depth, perspective and insight into the Great War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: a timeline to war appeared first on OUPblog.

By Matt O’Keefe

Over ten years in the making, Mark Waid and Barry Kitson’s Empire is finally back. Volume 2 just debuted as on Thrillbent as a comic. I spoke to Mark about transitioning the series and updates on Thrillbent’s iOS app and new subscription model service.

Can you describe Empire for those who haven’t read it?

Empire is the story of what happens when a bad guy wins. Empire is the story of Golgoth, an armored despot who has supreme power and had a ten year plan to take over and earth and rule it in totality, and in eight years he knew two things for certain. One was that he was going to win and the other was that he didn’t want the job anymore because once he assimilates all the power onto one throne that makes him the target. That makes the throne the most deadly place in the world.

Golgoth is ruler of all he surveys, and there’s no opposition. There is no Justice League or Avengers to topple his rule. He’s won flat-out, but the question now is what happens next. What do you for an encore once you’re conquered the world?

What drove you to continue a print series as part of Thrillbent instead of create a new concept?

Ever since Barry Kitson and I did the original Empire back in the early-2000s we’ve wanted to do a sequel, but we had to wait until the right time when we were both available, and after we reclaimed the rights from DC. Now that we have it back, we’re full steam ahead. The reason we’re going to Thrillbent is because I own it, and as a publishing platform it was the perfect place for us. When you couple that with us rebranding Thrillbent as a premium subscription service for creator-owned books, Empire was a no-brainer as a flagship, because every store signing, every convention I’m asked when will more Empire come out. Well that day is tomorrow.

Is Empire Volume 2 in the Thrillbent format?

Yeah. It’s taking advantage of everything Thrillbent can do on a digital platform.

Had you started scripting it in traditional comics format?

No. We had a bunch of notes we had a bunch of ideas half-written ideas and half-written emails and notes written on napkins but really it wasn’t until we reclaimed the rights that we got very serious about it. Thankfully it was very easy to step back into that world which bodes well for us.

How has a comics veteran like Barry Kitson transitioned to the new format?

Very well. By his own admission he was nervous about it but Barry is a very, very smart man and he’s a brilliant storyteller so it really wasn’t much of a challenge for him at all. He got it right off the bat and he’s adapting very well to what digital can do and bringing a surprise to every page turn.

And Troy Peteri is lettering the book?

Yep. And Chris Sotomayor, who colored the original Empire, is back on board to join us with this.

Troy Peteri letters a big portion of the Thrillbent line. Has that that consistency helped the comics-making process?

Yeah he’s an invaluable part of the Thrillbent team. It’s not just that he gives us consistency, it’s that he understands every part of the process and he understands what digital can do. He’s not just treating it like a side job and instead treating it like a vocation and I’m thrilled about that.

Is Empire Volume 2 a finite story?

Yes, but not a short one. At least as long as Volume 1. You can certainly pick up Volume 2 without reading Volume 1 if you’re so inclined because we recap in those first few pages. But if you want to delve into volume 1 which is out-of-print and not easily accessible, when you subscribe to Thrillbent we are throwing in the Volume 1 192-page edition as well.

Why did you decide to stop offering downloads on Thrillbent?

We actually had been offering the files as downloads on the site and we were doing that specifically because we were building an audience. The reason we were offering the files as downloads was because people were going to pirate and share them anyway so we figured we may as well give them a quality copy that had our names on it. We did that for a few years and that served its purpose in getting the word out, but we’re moving into a new phase.

I’ll be brutally honest with you. We’re at a point that if we want to keep doing what we’re doing and keep pushing forward like we have been and keep producing new material that is going to attract an increasingly sizeable audience, we need to create a mechanism by which we can sell people early access to material that will eventually be free on the site–the Hulu/Hulu Plus model, if you will. That said, we’re bending over backward to give you way, way, way more in value than we are asking for in compensation. Even if you’re reading Empire and nothing else on Thrillbent you’re getting $3.99 worth of content every month. If you add to the other Thrillbent series you have access to, and our 300+ comic back catalogue, and the free 192-page Empire graphic novel, I think your $3.99 is well-spent.

What’s surprised you about the response to the Thrillbent app?

That people are embracing it like you wouldn’t believe. I was nervous that people would look at this and go, “Oh wait, you’re charging now? Well then i’m not interested” and certainly that made me nervous, but what pleasantly surprised me was the number of fans who stepped up and said that they appreciated getting two years worth of content so far and “how can we help you keep delivering that content at a fair price?” That was awesome.

And Insufferable is returning soon?

Yes, Insufferable will be coming back with Volume 3. We haven’t set a date; it will almost certainly be coming out after San Diego at this point. But in the meantime we have James Tynion who has been writing Batman Eternal over at DC writing a new series for us called The House in the Wall which will premiere next month. We have a brand-new series from a fantasy writer named Seanan McGuire. She’s terrific. She brings a whole new audience to Thrillbent because frankly her fan base is bigger than mine so, Seanan, please come aboard. She’ll be doing new material for us next month as well, and we’ll have many more announcements to roll out over the summer.

You can now read Empire with a subscription on the app or at thrillbent.com.

By: ChloeF,

on 4/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

conflict,

History,

Politics,

cold war,

Europe,

martin thomas,

regimes,

torture,

algeria,

democratic,

colonial,

empire,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

fight or flight,

decolonization,

rebeliion,

Add a tag

By Martin Thomas

Britain’s impending withdrawal from Afghanistan and France’s recent dispatch of troops to the troubled Central African Republic are but the latest indicators of a long-standing pattern. Since 1945 most British and French overseas security operations have taken place in places with current or past empire connections. Most of these actions occurred in the context of the contested end of imperial rule – or decolonization. Some were extraordinarily violent; others, far less so. Historians, investigative journalists and leading intellectuals, especially in France, have pointed to extra-judicial killing, systematic torture, mass internment and other abuses as evidence of just how dirty decolonization’s wars could be. Some have gone further, blaming the dismal human rights records of numerous post-colonial states on their former imperial rulers. Others have pinned responsibility on the nature of decolonization itself by suggesting that hasty, violent or shambolic colonial withdrawals left a power vacuum filled by one-party regimes hostile to democratic inclusion. Whatever their accuracy, the extent to which these accusations have altered French and British public engagement with their recent imperial past remains difficult to assess. The readiness of government and society in both countries to acknowledge the extent of colonial violence indicates a mixed record. In Britain, media interest in such events as the systematic torture of Mau Mau suspects in 1950s Kenya sits uncomfortably with the enduring image of the British imperial soldier as hot, bothered, but restrained. Recent Foreign and Commonwealth Office releases of tens of thousands of decolonization-related documents, apparently ‘lost’ hitherto, may present the opportunity for a more balanced evaluation of Britain’s colonial record.

In France, by contrast, the media furores and public debates have been more heated. In June 2000 Le Monde’s published the searing account by a young Algerian nationalist fighter, Louisette Ighilahriz, of her three months of physical, sexual and psychological torture at the hands of Jacques Massu’s 10th Parachutist Division in Algiers at the height of Algeria’s war of independence from France. Ighilahriz’s harrowing story helped trigger years of intense controversy over the need to acknowledge the wrongs of the Algerian War. After years in which difficult Algerian memories were either interiorized or swept under capacious official carpets, big questions were at last being asked. Should there be a formal state apology? Should decolonization feature in the school curriculum? Should the war’s victims be memorialized? If so, which victims? Although the soul-searching ran deep, official responses could still be troubling. On 5 December 2002 French President Jacques Chirac, himself a veteran of France’s bitterest colonial war, unveiled a national memorial to the Algerian conflict and the concurrent ‘Combats’ (using the word ‘war’ remained intensely problematic) in former French Morocco and Tunisia. France’s first computerized military monument, the names of some 23,000 French soldiers and Algerian auxiliaries who died fighting for France scrolled down vertical screens running the length of the memorial columns.

Paris monument to Algerian War dead: author’s own photograph.

No mention of the war’s Algerian victims, but at least a start. Yet, seven months later, on 5 July 2003, another unveiling took place. This one, in Marignane on Marseilles’ outer fringe, was less official to be sure. A plaque to four activists of the pro-empire terror group, the Organisation de l’Armée secrète (OAS), carries the inscription ‘fighters who fell so that French Algeria might live’. Among those commemorated were two of the most notorious members of the OAS. One was Roger Degueldre, leader of the ‘delta commandos’, who, among other killings, murdered six school inspectors in Algeria days before the war’s final ceasefire. The other was Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry, organizer of two near-miss assassination attempts on Charles de Gaulle, first President of France’s Fifth Republic. Equally troubling, it took the threat of an academic boycott in 2005 before France’s Council of State advised President Chirac to withdraw a planned stipulation that French schoolchildren must be taught the ‘positive role of the French colonial presence, notably in North Africa’.

One explanation for the intensity of these history wars is that few France and Britain’s colonial fights since the Second World War were definitively won or lost at identifiable places and times. The fall of the French fortress complex at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the climax of an eight-year colonial war over Vietnam’s independence from France, was the exception, not the rule. Not surprisingly, its anniversary has been regularly celebrated by the Vietnamese Communist authorities since then.

Elsewhere it was harder for people to process victory or defeat as a specific event, as a clean break offering new beginnings, rather than as an inconclusive process that settled nothing. Officials in British Kenya reported that the Mau Mau rebellion, rooted among the colony’s Kikuyu majority, was ‘all but over’ by the end of 1955. Yet emergency rule continued almost five years more. To the East, in British Malaya, a larger and more long-standing Communist insurgency was in almost incessant retreat from 1952. Surrender terms were laid down in September 1955. Two years later British aircraft peppered the Malayan jungle, not with bombs but with thirty-four million leaflets offering an amnesty-for-surrender deal to the few hundred guerrillas who remained at large. Even so Malaya’s ‘Emergency’ was not finally lifted until 1960.

In the two decades that followed, the Cold War migrated ever southwards, acquiring a more strongly African and Asian dimension. The contest between liberal capitalism and diverse models of state socialism became a battle increasingly waged in regions adjusting to a post-colonial future. Some of the bitterest conflicts of the 1960s to the 1990s originated in fights for decolonization that morphed into intractable proxy wars in which civilians often counted amongst the principal victims. In the late twentieth century France and Britain avoided the worst of all this. Should we, then, celebrate the fact that most of the hard work of ending the British and French empires was done by the dawn of the 1960s? I would suggest otherwise. For every instance of violence avoided, there were instances of conflict chosen, even positively embraced. Often these choices were made in the light of lessons drawn from other places and other empires. Just as the errors made sometimes caused worst entanglements, so their original commission reflected entangled colonial pasts. Often messy, always interlocked, these histories remind us that Britain and France travelled their difficult roads from empire together.

Martin Thomas is Professor of Imperial History at the University of Exeter. This post is partially extracted from Fight or Flight: Britain, France, and their Roads from Empire

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Two difficult roads from empire appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 3/22/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

tapestry,

magna carta,

bates,

david bates,

the normans and empire,

tournai marble,

civilising,

History,

France,

British,

normandy,

bayeux,

normans,

empire,

British history,

French History,

*Featured,

the normans,

Add a tag

By David Bates

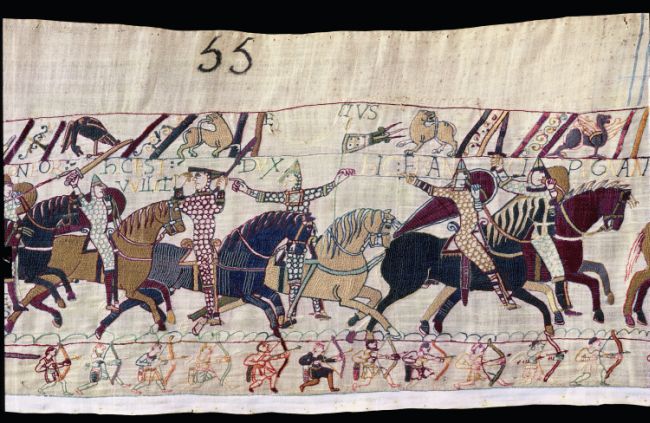

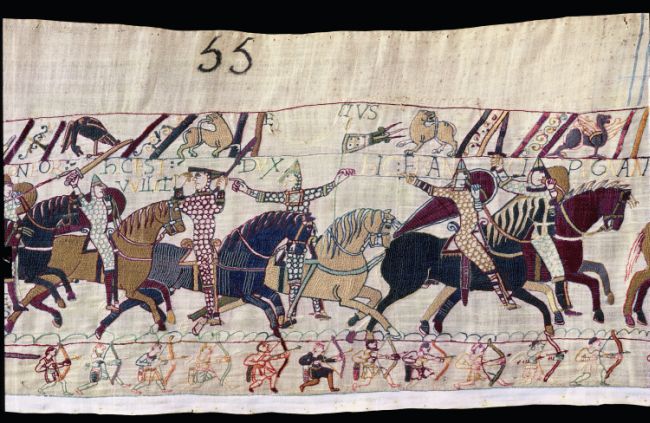

The expansion of the peoples calling themselves the Normans throughout northern and southern Europe and the Middle East has long been one of the most popular and written about topics in medieval history. Hence, although devoted mainly to the history of the cross-Channel empire created by William the Conqueror’s conquest of the English kingdom in 1066 and the so-called loss of Normandy in 1204, I wanted to contribute to these discussions and to the ongoing debates about the impact of this expansion on the histories of the nations and cultures of Europe. That peoples from a region of northern France should become conquerors is one of the apparently inexplicable paradoxes of the subject. The other one is how the conquering Normans apparently faded away, absorbed into the societies they had conquered or within the kingdom of France.

In 1916 Charles Homer Haskins’ made the statement that the Normans represented one of the great civilising influences in European – and indeed world – history. If, a century later, hardly anyone would see it thus, the same imperatives remain, namely to locate the Normans within a context in which it remains popular to write national histories, and, for some, in the midst of debates about the balance of the History curriculum, to see them as being of paramount importance. The history of the Normans cuts across all this, but is an inescapable subject in relation to the histories of the English, French, Irish, Italian, Scottish, and Welsh. Those currently fashionable concepts – and rightly so – ‘The First English Empire’ and ‘European change’ are also at the centre of the debates.

As a concept, empire is nowadays both fashionable and much argued about, a universal phenomenon of human history that has been the subject of several major television programmes. It is a subject that requires a multidisciplinary approach. Over the last two millennia, statements by both contemporaries and subsequent commentators have often set a proclaimed imperial civilising mission as a positive feature against the impact of violence and the social and cultural subjugation of the subjects of an empire. Seen thus, the concept of empire has an obvious relevance to the subject of the Normans. And, in relation to the pan-European expansion of the Normans, and, in particular, to the creation of the kingdom of Sicily, the term diaspora, as it is understood in the social sciences, constitutes a persuasive framework of analysis. Taken together, the two terms empire and diaspora create a world in which individuals and communities had to adapt rapidly to new forms of power and cultures and in which identities are multiple, flexible, and often uncertain. For this reason, the telling of life-histories is of central importance rather than simplified notions of social and cultural identity. One consequence must be the abandonment of the currently popular and unhelpful word Normanitas. The core of this book is a history of power, diversity and multiculturalism in the midst of the complexities of a changing Europe.

The use of terms such as hard power, soft power, hegemony, core and periphery, and cultural transfer can be used to frame interpretations of many national histories, including Welsh, Scottish, and Irish, as well as English. The crucial points in all cases are the mixture of engagement with the dominant imperial power and the perpetuation of difference and diversity through the exercise of agency beyond the core. The framework is one that works especially well in relation to the evolving histories of the Welsh kingdoms/principalities and of the kingdom of Scots. It also means that the so-called ‘anarchy’ of 1135 to 1154, the succession dispute between King Stephen and the Empress Matilda becomes a civil war which needs to be set in a cross-Channel context and through which there were many continuities. And Magna Carta (1215), of which the eight-hundredth anniversary is fast approaching, becomes a consequence of imperial collapse. However, a focus on England and the British Isles just does not work. Normandy’s centrality to the history of the cross-Channel empire created in 1066 is of basic importance. Both morally and militarily the creation of the cross-Channel empire brought problems of a new kind that were for some living, or mainly domiciled, in Normandy a source of anguish. The book’s cover has indeed been chosen with this in mind. It shows troubled individuals who have narrowly escaped disaster at sea, courtesy of St Nicholas. But they successfully made the crossing. And so, of course, did the Tournai marble on which they are carved.

Professor David Bates took his PhD at the University of Exeter, and over a professional career of more than forty years, he has held posts in the Universities of Cardiff, Glasgow, London (where he was Director of the Institute of Historical Research from 2003 to 2008), East Anglia, and Caen Basse-Normandie. He has worked extensively in the archives and libraries of Normandy and northern France and has always sought to emphasise the European dimension to the history of the Normans. ‘He currently holds a Leverhulme Trust Emeritus Fellowship to enable him to complete a new biography of William the Conqueror in the Yale University Press English Monarchs series. His latest book is The Normans and Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Section of the Bayeaux Tapestry, courtesy of the Conservateur of the Bayeux Tapestry. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The Normans and empire appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 3/17/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

WWII,

Videos,

World War II,

World,

Multimedia,

British,

Europe,

empires,

martin thomas,

colonization,

Second World War,

roads,

empire,

*Featured,

UKpophistory,

fight or flight,

british empire,

French Empire,

imperial history,

decolonization,

leverhulme,

and discusses,

abnbnaed0dk,

9qwpenmcrqw,

exeter,

Add a tag

After the Second World War ended in 1945, Britain and France still controlled the world’s two largest colonial empires, even after the destruction of the war. Their imperial territories extended over four continents. And what’s more, both countries seemed to be absolutely determined to hold on their empires; the roll-call of British and French politicians, soldiers, settlers, and writers who promised to defend their colonial possessions at all costs is a long one. But despite that, within just twenty years, both empires had vanished.

In the two videos below Martin Thomas, author of Fight or Flight: Britain, France, and their Roads from Empire, discusses the disintegration of the British and French empires. He emphasizes the need to examine the process of decolonization from a global perspective, and discusses how the processes of decolonization dominated the 20th century. He also compares and contrasts the case of India and Vietnam as key territories of the British and French Empires.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Martin Thomas is Professor of Imperial History in the Department of History at the University of Exeter, where he has taught since 2003. He founded the University’s Centre for the Study of War, State and Society, which supports research into the impact of armed conflict on societies and communities. He is a past winner of a Philip Leverhulme prize for outstanding research and a holder of a Leverhulme Trust Major Research Fellowship. He has published widely on twentieth century French and imperial history, and his new book is Fight or Flight: Britain, France, and their Roads from Empire.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Britain, France, and their roads from empire appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 12/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

UKpophistory,

1800-1928,

1928-2008,

Cannabis Britannica,

Cannabis Nation,

Control and consumption in Britain,

ganja,

James H. Mills,

trade and prohibition,

History,

UK,

Current Affairs,

empire,

cannabis,

*Featured,

Law & Politics,

Add a tag

By James H. Mills

It was announced on 10 December as an outcome of the recent Commission into cannabis that the UK Government has decided to reorganise its ‘ganja administration’ with the objective of taxing sales of the drug in order to generate revenues and to control the price in order to discourage excessive consumption. The Government will work with partners from the private sector to ensure that products of a consistent quality are available to consumers. A source at one of the cannabis corporations has stated that they are happy to make a full contribution to the Government’s finances, although critics have argued that they deploy a range of strategies to avoid paying tax.

The Home Affairs Committee’s Ninth Report, with the title Drugs: Breaking the Cycle, generated plenty of controversy early in December when the Prime Minister rejected its recommendation that a Royal Commission on Drugs Policy be established. The controversy may well have been a furore had an announcement along the lines of the above been included in its pages. Yet mention in the Committee’s report of state cannabis monopolies, of the legal consumption of the drug, and of permissive control regimes in faraway countries, invite comparisons to a previous period in British history, as does the Prime Minister’s allusion to a Royal Commission. This was a period when the paragraph above would have raised few eyebrows as British tax collectors skimmed off revenues from some of the world’s largest cannabis consuming societies.

The period, of course, is the 1890s. The Commission in question was the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission which was ordered in the House of Commons in 1893 and which reported in 1894. This Commission was the forerunner of the better known Royal Opium Commission which came to its conclusions in 1895. The enquiry into ‘Indian Hemp’, or cannabis, was focused on the colonial administration in India and its handling of the cannabis trade there. Critics of the opium trade had discovered that the Government of India was also making money from cannabis through a tax on the local market there, and seized on this as further evidence of the corruption of British rule. William Caine, one of the most passionate of these critics declared that cannabis was ‘the most horrible intoxicant the world has yet produced’ and started a campaign that forced the inquiry.

What the inquiry revealed was a thriving market for cannabis products in Britain’s colonies in south Asia. These substances had long-been been used for medication and intoxication there, and complex local beliefs about their uses and dangers were well-established before the British arrived. Colonial scientists and doctors proved to be curious about the potential of cannabis, and William O’Shaughnessy, Professor of Chemistry and Medicine in the Medical College of Calcutta, championed its virtues as a wonder-drug in the 1840s. However, the most sustained interest in the substance on the part of the British was from the Excise officials charged with taxing it as by the 1890s revenue from commercial cannabis was in the region of £150000 per annum, or around nine million pounds in today’s money.

Many of these officials worked readily alongside India’s cannabis producers in the trade. One magistrate reported that ‘they are singularly peaceable and law abiding and they are remarkably wealthy and prosperous’ and went on to note that:

The ganja cultivators contributed amongst them Rs. 5000 for the creation of the Higher English School at Naugaon. If a road or a bridge is wanted, instead of waiting for the tardy action of a District Board or committing themselves to the tender mercies of the PWD the cultivators raise a subscription among themselves and the road or bridge is constructed.

Other British officials were more suspicious of these producers however. As early as the 1870s fears were expressed that all manner of strategies were devised by those in the trade to evade the administration’s efforts to tax it. Storing crops away from the eyes of inspectors, claiming that fires had destroyed full storage facilities and clandestine shipments of the drug were all uncovered. Officials regularly swapped stories like the following:

In December, a couple of police constables and a village watchman were, about 9pm, on their way to Bálihar, when they saw two persons crossing the field with something on their heads. On their shouting out, the men dropped their loads and ran off. It was then found that they had dropped 36 ½ kutcha seers of flat hemp. The drug was taken possession of by the constables but the culprits were never traced.

Perhaps because of such episodes the British continued to tighten their grip on commercial cannabis into the twentieth-century and reforms in the wake of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission included price fixing, government-controlled warehousing of all crops, and licensing of both wholesale and retail transactions. The example of cannabis-taxation in India was followed elsewhere, with colonial administrations as far apart as Burma and Trinidad abandoning initial attempts at prohibition. In fact it emerged in 1939 that the Government in India had been supplying cannabis to markets in both Burma and Trinidad in contravention of the international controls on the drug that had been imposed in 1925 at the Geneva Opium Conference.

While the Home Affairs Committee is right to look to current experiments with control regimes for cannabis in Washington, Colorado and Uruguay, perhaps the stories above are reminders that British history too provides plenty of evidence for assessing ‘the overall costs and benefits of cannabis legalisation’. These stories provide glimpses of a world where cannabis transactions provide state revenues rather than act as drains on resources, where suppliers club together to pay for educational facilities rather than hang around school-gates plying their wares, and where doctors work freely with a useful drug. But they also seem to warn of the moral complexities of state-sponsored markets in psycho-active substances, and of the problems that any control system will face when confronted by those keen to maximise their profits from such drugs.

James H. Mills is Professor of Modern History at the University of Strathclyde and Director of the Strathclyde hub of the Centre for the Social History of Health and Healthcare (CSHHH) Glasgow. Among his publications are Cannabis Nation: Control and consumption in Britain, 1928-2008, (Oxford University Press 2012), Cannabis Britannica: Empire, trade and prohibition, 1800-1928, (Oxford University Press 2003) and (edited with Patricia Barton) Drugs and Empires: Essays in modern imperialism and intoxication, 100-1930, (Palgrave 2007). The extracts above are all taken from his books.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of cannabis indica foliage bygaspr13 via iStockphoto.

The post Ganja administration appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lauren,

on 10/28/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

christianity,

emperor,

constantine,

This Day in History,

Europe,

Rome,

Roman Empire,

empire,

*Featured,

this day in world history,

constantine’s,

licinius,

maxentius,

toleration,

liberty”—evidence,

Add a tag

This Day in World History - Control of the Roman Empire was in the balance when the armies of Constantine and his brother-in-law Maxentius clashed near the Milvian Bridge, north of Rome. Despite having a smaller army, Constantine triumphed—a victory made secure when Maxentius drowned in the Tiber River while trying to escape. Constantine’s victory left him in command of the western half of the Roman Empire—but it also had more significant consequences.

By: Kirsty,

on 8/1/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Africa,

UK,

Videos,

Video,

australia,

crime,

Multimedia,

christopher,

prison,

britain,

punishment,

emma,

criminals,

empire,

slave trade,

*Featured,

a merciless place,

emma christopher,

merciless,

misjudgement,

desertions,

jzzclcrh1zu,

convicts,

Add a tag

A Merciless Place is a story lost to history for over two hundred years; a dirty secret of failure, fatal misjudgement and desperate measures which the British Empire chose to forget almost as soon as it was over.

By: Michelle,

on 6/14/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

podcast,

History,

Politics,

Current Events,

Iraq,

A-Featured,

World History,

empires,

parsons,

Roman Empire,

Washington University,

shorter,

empire,

Rule of Empires,

Tim Parsons,

US foreign policy,

slower,

endured,

impose,

pod4,

Add a tag

Michelle Rafferty, Publicity Assistant

Recently Tim Parsons, Professor of African History at Washington University and author of Rule of Empires: Those Who Built Them, Those Who Endured Them, and Why They Always Fall, stopped by Oxford with his wife Ann. In the following podcast Ann asks Tim a few questions about his book and what empires past can tell us about the present.

Michelle Rafferty: Today we have a special treat here at Oxford. I’m here with Tim Parsons and his wife Ann Parsons, and Ann is actually going to interview Tim. Here we go.

Ann Parsons: Your specialty is African History. What motivated you to write a book about empires worldwide?

Tim Parsons: Well in the past as a social historian of Africa I’ve written books about common people, which means I write about how common people live their daily lives, and in this case, in studying East Africa, I’ve looked at how East Africans, average people, experienced empire. And one of the things that troubled me is in the last ten years we’ve heard a lot about how empires can be benevolent, civilizing, how they were forces for global order and security, and how then the way to solve the problem of Saddam Hussein in Iraq and the global war on terror, was that the United States should impose an empire from above, and that this would be the way to restore order to the world. And as someone who has studied empire from the bottom up, that I see the true realities of empire, I knew from the start in 2003 that this was a very bad idea. One of the things that I felt I had to do was make this case, I had to actually talk about empires historically, to go back in time and to see if what I know about the British Empire in East Africa held true all the way back to the Roman Empire because that’s what many of the current proponents of empire now, cite.

Ann: So then what do these historical empires tell us about the present?

Tim: Well, first of all they us that it’s really a very bad idea to cite ancient civilizations as examples for modern American foreign policy. In others words, empires, if we go back 2,000 years to the Roman Empire, if we even go back to the 15th century Spanish Empire in the Americas, yes those empires did last a long time, but one of the reasons why they did is because things were very different back then. The communication was much slower, transportation was much slower, they were largely agrarian societies when literacy was not very widespread, and most identities, which means how people identified themselves, were local and confined to the village level. And in those times it was very easy to conquer many villages and then to impose rule from above. So that made these empires appear much more stable than they actually really were. And what you find out, if you at the history of empire over time, you see that the lifespan of empires gets shorter, and shorter, and shorter, to the point, as I argue in the book, that empires today don’t exist.

Critics on the left of American policy in the last maybe 50 years have branded the United States as a new empire, as the new Rome because they don’t like American foreign policy, because they don’t like the exertion of American force around the world. And that’s a problem I think, because by calling the United States an empire they are missing the true definition of empire. An empire is direct formal rule. They fail to recognize that it’s not the question of whether the United States is an empire or not, it’s that they should point out using empire as a model is a very bad idea because empir

By: Kirsty,

on 12/14/2009

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

books,

Literature,

fiction,

UK,

A-Featured,

south africa,

anne of green gables,

Prose,

OWC,

l.m. montgomery,

09,

J. M. Coetzee,

boyhood,

elleke boehmer,

empire,

postcolonial,

Add a tag

By Kirsty McHugh, OUP UK

It has become a holiday tradition on the OUPblog to ask our favorite people about their favourite books.  This year we asked authors to participate (OUP authors and non-OUP authors). For the next two weeks we will be posting their responses which reflect a wide variety of tastes and interests, in fiction, non-fiction and children’s books. Check back daily for new books to add to your 2010 reading lists. If that isn’t enough to keep you busy next year check out all the great books we have discovered during past holiday seasons: 2006, 2007, 2008 (US), and 2008 (UK).

This year we asked authors to participate (OUP authors and non-OUP authors). For the next two weeks we will be posting their responses which reflect a wide variety of tastes and interests, in fiction, non-fiction and children’s books. Check back daily for new books to add to your 2010 reading lists. If that isn’t enough to keep you busy next year check out all the great books we have discovered during past holiday seasons: 2006, 2007, 2008 (US), and 2008 (UK).

Elleke Boehmer is Professor of World Literature at Wolfson College, Oxford and is internationally known for her research in postcolonial writing and theory, and the literature of empire. She has written or edited five books for OUP: Scouting for Boys, Empire Writing, Nelson Mandela: A Very Short Introduction, Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890-1920, and Colonial and Postcolonial Literature.

My favourite books keep changing their line-up, with new number ones jostling for attention in phases, depending on shifting interests and moods.

As far as my favourite children’s book is concerned however I will always come back to LM Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, 101 this year, which I must first have read aged about 11 and like so many bookish provincial girls the world over related to at once. As the tale of the parentless redhead who grows up with elderly Matthew and Marilla in Canada’s smallest province, Prince Edward Island, where the soil is as red as her hair, Anne is the ultimate ugly duckling girl’s story. What young teenage reader of that era, I wonder, would not have identified with harum-scarum Anne in her quest for family, friendship, poetry and love, in roughly that order, and who succeeds in that quest without losing her charm and her propensity for falling into ‘scrapes’? I certainly identified, with a vengeance, to the extent that, aged 17, I railroaded and cycled all the way from Toronto to PEI in order to see Anne’s island for myself.

My favourite book for adults at the present time is another story about a child, this time a boy, JM Coetzee’s Boyhood, the first in his ‘self-cannibalizing’ trilogy (to quote Zadie Smith) Scenes from Provincial Life. Boyhood presents as a fiction, in memoir form, as some of the scenes appear to emerg

While I understand that every customer is a great and awesome customer, I am super-curious what percentage of the “print math” customers have signed up to be Thrillbent-subscriber customers?

(Not one thing would make me happier than “150%, byotch!”, but my guess is it is in the “under 1/3″ range?)

-B