By Russ Castronovo

Ever since 4 July 1777 when citizens of Philadelphia celebrated the first anniversary of American independence with a fireworks display, the “rockets’ red glare” has lent a military tinge to this national holiday. But the explosive aspect of the patriots’ resistance was the incendiary propaganda that they spread across the thirteen colonies.

Sam Adams understood the need for a lively barrage of public relations and spin. “We cannot make Events; Our Business is merely to improve them,” he said. Exaggeration was just one of the tricks in the rhetorical arsenal that rebel publicists used to “improve” events. Their satires, lampoons, and exposés amounted to a guerilla war—waged in print—against the Crown.

While Independence Day is about commemorating the “self-evident truths” of the Declaration of Independence, the path toward separation from England relied on a steady stream of lies, rumor, and accusation. As Philip Freneau, the foremost poet-propagandist of the Revolution put it, if an American “prints some lies, his lies excuse” because the important consideration, indeed perhaps the final consideration, was not veracity but the dissemination of inflammatory material.

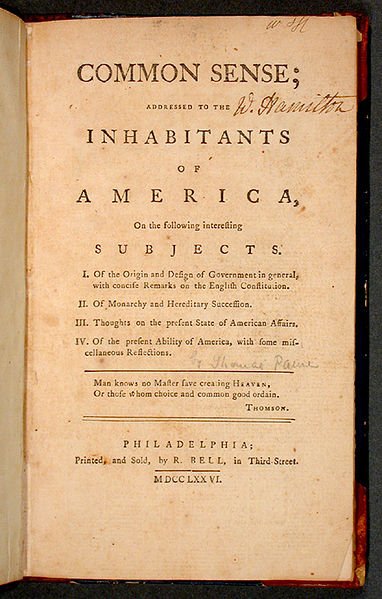

In place of measured discourse and rational debate, the pyrotechnics of the moment suited “the American crisis”—to invoke the title of Tom Paine’s follow-up to Common Sense—that left little time for polite expression or logical proofs. Propaganda requires speed, not reflection.

Writing became a rushed job. Pamphlets such as Tom Paine’s had an intentionally short fuse. Common Sense says little that’s new about natural rights or government. But what was innovative was the popular rhetorical strategy Paine used to convey those ideas. “As well can the lover forgive the ravisher of his mistress, as the continent forgive the murders of Britain,” he wrote, playing upon the sensational language found in popular seduction novels of the day.

The tenor of patriotic discourse regularly ran toward ribald phrasing. When composing newspaper verses about King George, Freneau took particular delight in rhyming “despot” with “pisspot.” Hardly the lofty stuff associated with reason and powdered wigs, this language better evokes the juvenile humor of The Daily Show.

The skyrockets that will be “bursting in air” this Fourth of July are a vivid reminder of the rhetorical fireworks that galvanized support for the colonists’ bid for independence. The spread of political ideas, whether in a yellowing pamphlet or on Comedy Central, remains a vital part of our national heritage.

Russ Castronovo teaches English and American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His most recent book is Propaganda 1776: Secrets, Leaks, and Revolutionary Communications.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Rhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of July appeared first on OUPblog.

The first time I met Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy I was ten years old. Every Thursday I had a date with Marmee, I mean mom, as she stood there ironing. To make her arduous task go by faster, I read Little Women to her. Orchard House seemed the perfect setting to iron in and besides it was a family we felt we related to. Though 100 and some years had passed since Jo wrote plays for her sisters, our 1970’s/80’s household seemed to hold the same passions and desires. All we really needed was Laurie living next door and a mean old aunt who wanted us to read to her. Hey wasn’t I already reading to somebody? There you have it — I was one step closer to being Jo March.

(Here is where my mother would want me to point out that she wasn’t ironing her husband and children’s clothes. She was a wedding dress designer; she always steamed and pressed the wedding and bridesmaids’ dresses on Thursdays so they could be packed and delivered on Fridays.)

That summer of Little Women was packed gently away in the recesses of my mind until many years later when I was, yet again, utterly lost on the Boston highways and by-ways. After what seemed like endless driving, I found myself in the little town of Concord Massachusetts. Passing before us were colorful clapboard colonial houses boasting quaint little gardens. As the country road kept turning and winding, I couldn’t help muttering every two minutes to my son, “We are so lost. If it wasn’t so nice to look at I’d be worried.” Just after one of those mutterings and country road turns I saw a sign for “Orchard House.” Surely that couldn’t be my Orchard House, could it? I made a hasty right-hand turn into the parking lot, and sitting before me was the Orchard House of my imagination — just as I had left it.

“Let’s get out of the car,” I said to my son, gazing at the house.

“Mom, do you know where we are?”

“I think so.” I started walking up towards the house.

“Mom, where are we going? Do you know these people?”

“Yes,” Came my quick reply. “We’re visiting some old friends.”

“Mom, who lives here? I thought we were lost.”

“The Marches live here. My friend Jo March and her sisters live here.”

By this time we had come to the kitchen door.

I knocked and without waiting for a reply I entered. There to greet us was a very kind woman who, I might add, looked an awful lot like Marmee.

“Are you here for the tour?” she asked.

“Tour?” I questioned.

“Yes, you’re at Louisa May Alcott’s house, author of Little Women.”

From there we got a private tour into the world of Louisa May Alcott and an up-close visit into the life and times of this cherished author. During our visit to Orchard House seeds were planted, and I just had to discover what ideas were to unfold. We decided to stay in Concord, or stay “lost,” as my son likes to put it.

Over the next three days, we met her, her family, and neighbors, all contributors to American education, thought and literature.

Louisa May Alcott was the second daughter of Bronson and Abigail May Alcott. Born on the same day as her father, on November 29th, 1832. Louisa was raised along with her sisters Anna, Elizabeth, and May in a very unique family.

Louisa’s father Bronson Alcott, a transcendentalist and educator, believed that the key to social reform and spiritual growth was at home and in family life. He woke his family everyday at 5 am to run outdoors. They would finish with a cold morning bath before starting their daily studies and chores. He was a philosopher who loved public speaking and often would stand outside his house to discuss his ideas with passersby. Next door neighbor Nathaniel Hawthorne, who was a very solitary and private man, had a path built above his house in the forest which led around the Alcott home and came out on the other side so he could avoid meetings with Bronson Alcott.

Concord looked at the Alcott’s as an eccentric family. The Alcott family made many life choices which contributed to them standing out from the rest of their community.

Louisa and her sisters were home-schooled, taught by their father until 1848. He instilled in them the values of self-reliance, duty, charity, self-expression and sacrifice. Noticing how bright and curious Louisa was, Ralph Waldo Emerson, another neighbor, invited her to visit his library any time she wished. What followed was Mr. Emerson becoming her literature and philosophy teacher. They would spend hours together discussing literature, thought, poetry, rhetoric and the like. Another of Louisa’s teachers was naturalist and essayist Henry David Thoreau. Louisa and her sisters accompanied him often on his long nature walks. Along with the art of nature observation he taught them biology.

Though Louisa’s father was a very educated man, he brought in little income. Louisa, her mother, and her sisters had to hire themselves out to clean houses, take in laundry, and work as tutors in schools. Louisa had been writing poems and stories under a couple of pseudonyms. She started using her own name when she was hired to write children’s stories. At the age of 15 she decided that her family would no longer live in poverty. The first book she wrote was Flower Fables, which she wrote for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s daughter Ellen Hawthorne. She wrote Little Women in ten weeks and the sequel Little Men in another ten week session. Both books were written at Orchard House and while we were visiting there we saw the small desk by the window that Bronson Alcott made her. All of her children’s books have been continually published since the late 1800’s and translated into 50 languages.

Louisa was a very strong-willed woman. During the Civil War she worked as a nurse in Washington D.C. There she contracted typhoid fever and the mercury used to cure her ended up poisoning her. She suffered from chronic illness for the rest of her life.

Her family was staunchly abolitionist and housed slaves moving towards freedom. John Brown’s widow and children stayed with the Alcott’s for several weeks after the death of Mr. Brown.

Like many educated women of her time, Louisa was an advocate for women’s suffrage. She was the first woman registered to vote some 40 years before women had the right to vote in the United States. Louisa walked into a school board election and pounded on the table saying “I have the right to vote and you won’t stop me.” The election chair gave her a ballot and registered her to vote. Whether her vote counted or not, no one knows, but people actively speak about Louisa as the first woman to vote in the United States.

As in her book Little Women, Louisa’s sister Beth died from smallpox, which she contracted taking care of a poor immigrant family. Later her sister Amy moved to Europe to study painting at the Beaux Arts in Paris. Amy married a Swiss man and later died after giving birth to her daughter who they named after her sister Louisa (Lulu). Upon the insistence of her sister, Louisa took care of Lulu at Orchard House until she was ten years old and then sent her back to Switzerland. The eldest of the Alcott sisters, Anne, loved to act just like the older sister Meg in Little Women. As I was walking up Walden Street in Concord I noticed a little theater which I learned was founded by Anne Alcott. To this day plays are performed there seasonally and a production of Little Women is an annual event.

Louisa never married and wrote until the day she died at 55 years old. Just as she was born on the same day as her father, she died just two days after his death.

We paid a visit to the Sleepy Hollow cemetery. This lovely place was created by Ralph Waldo Emerson as a place of beauty for the citizens of Concord to come and reflect on nature, literature, music, poetry, and their loved ones. As they were in life, all of the above-mentioned people are neighbors in death as well. As we approached Louisa’s grave in her family plot we took part in the tradition of leaving a pen at the authoress’s grave, as well as a stone on Henry David Thoreau’s grave just nearby. Walking a few feet we also paid homage to Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Since returning from Concord we’ve started our own family journal practice. In the Alcott household, journals were meant to be shared. The Alcott family would write about the daily happenings in their lives, what books they were reading and the thoughts they inspired, political opinions, women’s suffrage, plays they were working on or had seen, walks and observations, poems they had written and poems to be shared. Anything at all that held their attention would be written in their journals. Each evening after dinner they sat around the table and read from their journals.

In our family we’ve taken to collecting not just snippets from our daily lives but to writing down poems we’ve discovered during the week. We also include riddles, jokes, favorite recipes, and this week’s favorite music. The family journal sits on the old radio by the kitchen table where everyone puts something daily into it. On Sunday dinner we read from our weekly family journal. It’s been fun to watch what catches the eye of my growing family and how we are creating this weekly testament about the lives we share together.

By getting lost on our way back to Boston, we ended up in another era of American thought, literature, and history. Unbeknownst to me, I had no idea that by discovering Louisa May Alcott an entire world of famous American transcendentalist would plant the seeds of inspiration. Over those few days we walked the path of Henry David Thoreau, saw the birth of our nation at Minute Man National Park, and embraced the world of 19th century America.

For further information about Orchard House, Louisa May Alcott, her books, and the time period she lived in , please look here.

::::::::::::

The post Discovering the World of Louisa May Alcott and Little Women appeared first on Jump Into A Book.

I am a sucker for a great American novel, in particular ones set in college and this kind of fits into both those categories but with a twist. This was originally described to me as Wonderboys meets The Art of Fielding which isn’t necessarily true. Instead imagine a novel like Wonderboys or The Art of Fielding and then imagine what happens to the author and his family forty years later.

I am a sucker for a great American novel, in particular ones set in college and this kind of fits into both those categories but with a twist. This was originally described to me as Wonderboys meets The Art of Fielding which isn’t necessarily true. Instead imagine a novel like Wonderboys or The Art of Fielding and then imagine what happens to the author and his family forty years later.

A.N. Dyer is the author of Ampersand, a seminal work of American literature set in a college in the 1950s. It was the defining book of his career and is still held in reverence forty years later. A.N. Dyer, Andrew, is now an old man. He has three sons, two with his wife and one from an affair that ended his marriage. Following the death of his oldest and closest friend Andrew, sensing his own imminent mortality, tries to repair his damaged relationship with his sons.

Gilbert treads a fine line throughout the book between satire and metafiction dipping in and out of each almost perfectly. He deftly blurs the lines between fact and fiction in his fictitious world. The way his dissects the publishing industry is wickedly brilliant but the core of the novel is the relationship between fathers and sons and the battles fought over legacy and individualism. The story is narrated by Philipp Topping, the son of Andrew’s recently deceased best friend, who I wouldn’t go as far to say is an unreliable narrator but he definitely has his own biases. The story does take a slightly odd turn but Gilbert keeps everything on the road.

A clever story of fathers and sons and a tragic exploration of the great American novel and it’s aftermath.

Buy the book here…

By Peter Stoneley

The last couple of years have been an up-and-down period for the reputation of Mark Twain (1835-1910). It started well with a special issue of Time Magazine in 2008 which reminded readers of Twain’s goodness, and of the fact that the “buddy story of Huck and Jim was not only a model of American adventure and literature but also of deep friendship and loyalty.” This was followed in 2010 by many celebrations to mark the centenary of his death, including a volume in the prestigious Library of America series. Headlining Twain as the most “beloved” and “cherished” author from “around the world,” the Library of America volume was an anthology of “Great Writers on His Life and Work.”

But there has been another Twain waiting for his turn in the public eye. Laura Skandera-Trombley brought this Twain into view with her book of 2010 on “the hidden story of his final years”, revealing just how vain, bad-tempered and vengeful he could be. Far from the world of children and their buddies, a key fact about the revealed Twain was that his secretary had presented him with a sex toy. Then earlier this month the University of California Press published the first volume of their three-volume edition of Twain’s autobiography. This made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic. The autobiography had supposedly gone unpublished because it was so full of harsh truths about Twain’s contemporaries, his nation, and life generally that he himself had ordered that it not be published until 100 years after his death. Here Twain is in full spate, calling his secretary a “salacious slut,” settling many scores with business-partners who he thought had fleeced him, and referring to United States soldiers involved in imperial wars as “uniformed assassins.”

How can we go on seeing Twain as “the quintessential American” once we know that he had echoed Johnson’s comment that “patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel”? How can we see him as about “deep friendship and loyalty” when he conceived intense enmities for so many of his closest associates? It turns out that the Twain we had known was, as the New York Times put it, a “scrubbed and sanitized version,” and here in the autobiography was the truth. Similarly the Daily Telegraph assured its readers that the autobiography was “likely to shatter the myth that America’s great writer and humorist was a cheerful old man.”

We might seek to temper the coverage of the publication of the autobiography, as the outstanding editors responsible for the California volume have themselves done. Although it is a great event in Twain scholarship to have a full and reliable edition, substantial parts of the autobiography had been published before, including most of the truly interesting parts. The parts dealing with the “salacious” secretary were not part of the autobiography, but are to be published as an appendix to the California edition, and the material had been discussed in some detail in earlier scholarship. And the sex toy? As an editor at the Mark Twain Project, Benjamin Griffin, has pointed out on the University of California Press website, this was a “massager” that was marketed to men and women as treatment for “rheumatism, headaches, neuralgia, and other ailments,” and Twain recommended the device to friends with seemingly no awareness that it might also serve as “a masturbation aid for women.”

Now, with the 175th anniversary of Twain’s birth on 30th November 2010, I have no further revelations to add. Nor do I wish to try to adjudicate between the “good Twain” and the “bad Twain.” What strikes me is how these fluctuations and polarizations in the image of Twain in the past year or so are but one mo

I thought you might be interested in the upcoming John Updike Society Conference, Oct. 1-3, 2010, in Reading, Pa. The conference includes tours of sites - probably mentioned in this book - that are important to Updike's life and literature.

Sites include Updike's childhood home, the church where he was baptized, the family farm, his parents' grave site, and the Peanut Bar, where Updike frequently ate when he worked for his hometown paper, the Reading Eagle.

You can see more about the conference at the John Updike Society website, http://blogs.iwu.edu/johnupdikesociety.