new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: American Revolution, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 33

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: American Revolution in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Cassandra Gill,

on 10/19/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

American Revolution,

America,

George Washington,

This Day in History,

Europe,

Alexander Hamilton,

Yorktown,

*Featured,

Online products,

War of American Independence,

Battle of Yorktown,

Admiral Sir George Rodney,

Battle of the Saintes,

Benjamin Lincoln,

Charles O’Hara,

Comte de Rochambeau,

French navy,

Hamilton Yorktown,

Lord Cornwallis,

Siege of Yorktown,

Sir Henry Clinton,

Add a tag

The surrender of Lord Cornwallis’s British army at Yorktown, Virginia, on 19 October 1781 marked the effective end of the War of American Independence, at least in North America. The victory is usually assumed to have been Washington’s; he led the army that besieged Cornwallis, marching a powerful force of 16,000 troops down from near New York City to oppose the British. Charles O’Hara, The presence of the young Alexander Hamilton, one of Washington’s aides-de-camp, who led a light infantry unit in the final stages of the siege, adds to the sense of its being a great American triumph.

The post The French Victory at Yorktown: 19 October 1781 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Carolyn Napolitano,

on 8/9/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Amanda B. Moniz,

charitable activity,

From Empire to Humanity,

From Empire to Humanity: The American Revolution and the Origins of Humanitarianism,

historical perspectives,

history of philanthropy,

Books,

History,

american history,

American Revolution,

charity,

America,

policy,

*Featured,

humanitarianism,

Add a tag

As a historian of philanthropy, I have wrestled with how to bring historical perspectives to my my own gifts of time and money. I study philanthropists in North America, the British Isles, and the Caribbean in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The distant past, you might think, and of little concern to our philanthropic practices today.

The post How can history inform public policy today? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 9/11/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

democracy,

American Revolution,

slavery,

anniversary,

VSI,

rights,

British,

citizens,

Very Short Introductions,

monarchy,

*Featured,

magna carta,

VSI online,

Arts & Humanities,

Habeas Corpus,

10 things you need to know,

Nicholas Vincent,

Add a tag

This year marks the 800th anniversary of one of the most famous documents in history, the Magna Carta. Nicholas Vincent, author of Magna Carta: A Very Short Introduction , tells us 10 things everyone should know about the Magna Carta.

The post 10 things you need to know about the Magna Carta appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Becky Laney,

on 7/4/2015

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

2015,

2015 Cybils-eligible,

books reviewed in 2015,

picture books,

Nonfiction,

American Revolution,

j nonfiction,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,

review copy,

Add a tag

Gingerbread for Liberty: How A German Baker Helped Win the American Revolution. Mara Rockliff. Illustrated by Vincent X. Kirsch. 2015. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 32 pages. [Source: Review copy]

First sentence:

Everyone in Philadelphia knew the gingerbread baker. His honest face...his booming laugh...And, of course, his gingerbread--the best in all the thirteen colonies. His big, floury hands turned out castles and queens, horses and cows and hens--each detail drawn in sweet, buttery icing with the greatest skill and care. And yet, despite his care, there always seemed to be some broken pieces for the hungry children who followed their noses to the spicy-smelling shop. "No empty bellies here!" the baker bellowed. "Not in my America!"Premise/plot: Gingerbread for Liberty is the untold, near-forgotten story of Christopher Ludwick, a German-born American who loved and served his country during the American Revolution in the best way he knew how: by baking.

My thoughts: I loved, loved, loved, LOVED this one. I loved the end papers which feature a recipe for "Simple Gingerbread." I loved the illustrations. Never has a book's illustrations gone so perfectly-perfectly well with the text. The illustration style is very gingerbread-y. It works more than you think it might. At least in my opinion! I loved the author's note. I did. I loved learning a few more facts about Christopher Ludwick. It left me wanting to know even more. Which I think is a good thing. The book highlights his generosity and compassion as well as his baking talents.

But most of all, I loved the text itself, the writing style. The narrative voice in this one is super-strong. And I love the refrain: Not in MY America!

Text: 5 out of 5

Illustrations: 4 out of 5

Total: 9 out of 10

© 2015 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

By: AlanaP,

on 7/1/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

American Revolution,

military history,

America,

New England,

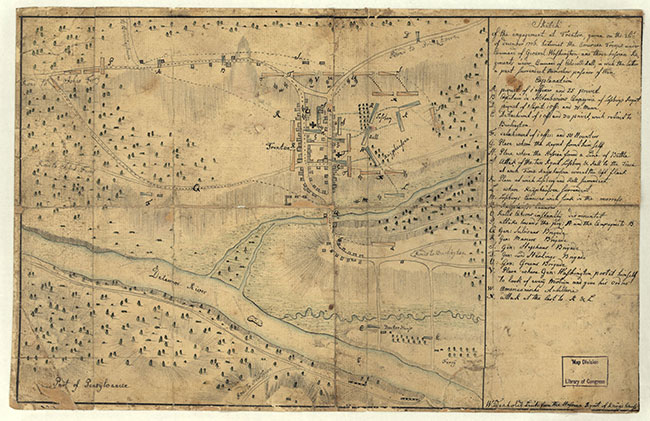

George Washington,

colonial America,

Continental Congress,

*Featured,

American independence,

David Hackett Fischer,

Revolutionary army,

Washington's Crossing,

Add a tag

It was March 17, 1776, the mud season in New England. A Continental officer of high rank was guiding his horse through the potholed streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Those who knew horses noticed that he rode with the easy grace of a natural rider, and a complete mastery of himself.

The post George Washington and an army of liberty appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 6/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

democracy,

American Revolution,

VSI,

British,

pope,

Very Short Introductions,

parliament,

French Revolution,

english civil war,

A Very Short Introduction,

King John,

*Featured,

richard II,

Medieval History,

magna carta,

VSI online,

Series & Columns,

1215,

800th anniversary,

barons,

Habeas Corpus,

Runnymede,

trial by jury,

Add a tag

On 15th June 2015, Magna Carta celebrates its 800th anniversary. More has been written about this document than about virtually any other piece of parchment in world history. A great deal has been wrongly attributed to it: democracy, Habeas Corpus, Parliament, and trial by jury are all supposed somehow to trace their origins to Runnymede and 1215. In reality, if any of these ideas are even touched upon within Magna Carta, they are found there only in embryonic form.

The post The greatest charter? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Molly Grote,

on 8/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

american history,

American Revolution,

Revolutionary War,

military history,

q&a,

America,

*Featured,

The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook,

Frances H. Kennedy,

John Ferling,

Journal of the American Revolution,

Add a tag

John Ferling is one of the premier historians on the American Revolution. He has written numerous books on the battles, historical figures, and events that led to American independence, most recently with contributions to The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook. Here, he answers questions and discusses some of the lesser-known aspects of the American Revolution.

What was the greatest consequence of the American Revolution?

The greatest consequence of the American Revolution stemmed from Jefferson’s master stroke in the Declaration of Independence. His ringing declaration that “all men are created equal” and all possess the natural right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” has inspired generations hopeful of realizing the meaning of the American Revolution.

What was the most underrated battle of the Revolutionary War?

King’s Mountain often gets lost in the shuffle, but if Washington’s brilliant Trenton-Princeton campaign was crucially important, King’s Mountain was no less pivotal. Washington’s victory was America’s first in nearly a year, King’s Mountain the first of significance in three years. Trenton-Princeton was vital for recruiting a new army in 1777; King’s Mountain stopped Britain’s recruitment of southern Tories in its tracks. Enemy losses were nearly identical at Trenton-Princeton and King’s Mountain. Finally, Sir Henry Clinton thought the defeat at King’s Mountain was pivotal, and soon thereafter he told one of his generals that with the setback “all his Dreams of Conquest quite vanish’d.”

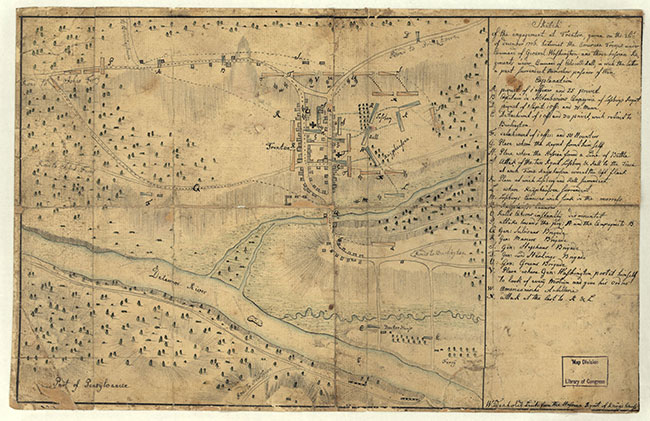

Sketch of the Battle of Trenton by Andreas Wiederholt (b. 1752?). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

What’s the one unanswered question about the American Revolution you’d most like answered?

The war in the South in 1780 and 1781 is shot through with mysteries. Why did Benjamin Lincoln stay put in Charleston in 1780? He might have withdrawn to the interior, as did those defending against Burgoyne’s invasion, or he might have made a stand behind the Ashley River — as Washington did on the Brandywine — and then retreated to the interior.

Why in the summer that followed did Horatio Gates immediately take the field when his army was so unprepared and he faced no immediate threat? Why did Gates in August at Camden position his men so that the militia faced Cornwallis’s regulars?

Why in 1781 did not Sir Henry Clinton order General Cornwallis back to the Carolinas or summon him and most of his army to New York?

With all the mistakes, maybe the biggest mystery of the war is how anyone won.

What is your favorite quote by a Revolutionary?

Aside from the egalitarian and natural rights portions of Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, I have two favorite quotations from revolutionaries. One is that of Captain Levi Preston of Danvers, Massachusetts. When asked why he had soldiered on the first day of the war, he responded: “[W]hat we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.” My second favorite is Washington’s remark on learning of Lexington and Concord: a “Brother’s Sword has been sheathed in a Brother’s breast.”

Aside from John and Abigail, what was the best husband-wife duo of the Revolution?

If “best” means the duo that best aided the American Revolution, I am sure there must have been countless nameless men who bore arms while their spouses at home made bullets. But of those with whom I am familiar, I opt for Joseph and Esther Reed. He played an important role in Pennsylvania’s insurgency, served in the army and as Washington’s secretary, played a crucial role in the Continental Army’s escape after the Second Battle of Trenton, sat in the Continental Congress, and was the chief executive of his state for three years. She organized the Ladies Organization in Philadelphia in 1780 and published a broadside urging women not to purchase unnecessary consumer items, but instead to donate the money that they saved to aid the soldiery in the Continental army. Altogether, her campaign raised nearly $50,000 in four states.

What was the most important diplomatic action of the war?

The greatest consequence of the American Revolution stemmed from Jefferson’s master stroke in the Declaration of Independence. His ringing declaration that “all men are created equal” and all possess the natural right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” has inspired generations hopeful of realizing the meaning of the American Revolution.

What is your favorite Revolutionary War site (battlefield, home, museum, etc.) to visit today?

If limited to choosing only one site, it would be Mount Vernon. For one thing, George Washington seemed to have a hand in almost everything that occurred in America from 1753 until his death in 1799. In addition, he was a farmer, a pursuit that is alien to most of us today. Mount Vernon includes an informative museum, a functioning distillery and mill, farm land, animals, gardens, and of course the mansion, which opens a window onto the life of a wealthy Virginia planter. Those who lived there as slaves are not overlooked and slavery at Mount Vernon is not whitewashed. Nearly a full day is required to take in everything and at day’s end a visitor who comes without much understanding of the man and his time will leave having received a decent and illuminating introduction to Washington and eighteenth century life and culture.

Propaganda was important during the Revolution. What is your favorite propaganda item?

Had there been an Abraham Zapruder armed with a motion picture camera on Lexington Green on 19 April 1775, we might know precisely what occurred when the first shot was fired in the Revolutionary War. But we will never know if that shot was fired accidentally, whether it was fired by British soldiers following orders, or as some alleged if it was fired by a colonist in hiding. What is known is that soon after that historic day the Massachusetts Committee of Safety deposed witnesses of the bloody event, from which it cobbled together an account showing that the regulars opened fire after being commanded to “Fire, by God, Fire.” That account circulated before the official British report was published. In a day when knowledge of who fired the first shot to launch a war was still important, the Massachusetts radicals had scored a propaganda master stroke.

If you could time travel and visit any American city, colony, or state for one year between 1763 and 1783, which would you choose?

I would choose to be living in Boston in 1763. I would like to know what people in the city were thinking about Anglo-America prior to the Sugar and Stamp Acts and how many had ever heard of The Independent Whig. I would like to visit grog shops to discover whether there was a hint of rebellion among the workers and whether they thought Samuel Adams would ever amount to anything. While there, perhaps I could catch a game at Fenway when the St. Louis Browns come to town.

In your opinion, what was George Washington’s biggest blunder of the war?

A book about Washington’s blunders would be large, but his most baffling mistake occurred in September and October 1776. Although fully aware that he was soon to be trapped in Harlem Heights by a superior British army and utterly dominant Royal Navy, Washington made no attempt to escape his snare. His letters at the time indicate an awareness of his dilemma. They also suggest that in addition to his customary indecisiveness, Washington was not just thoroughly exhausted, but in the throes of a black depression. These assorted factors likely explain his potentially fatal torpor. He and the American cause were saved from the looming disaster by the arrival of General Charles Lee, whose advice Washington still respected. Lee took one look and urged Washington to get the army out of the trap. Washington listened, and escaped.

In your opinion, who was the most overrated revolutionary?

Franklin is the most overrated. He was not unimportant – indeed, I think he was a very great man – but as he was abroad for years, he played a minor role in the insurgency between 1765 and 1775. Furthermore, while Franklin was popular in France, Vergennes was a realist who acted in the interest of his country. It is ludicrous to think that Franklin pulled his strings.

Who was the most underrated revolutionary?

General Nathanael Greene is so underrated that many today are unaware of him. But he was the general that Washington turned to for good advice, made personal sacrifices to try to straighten out the quartermaster corps, and waged an absolutely brilliant campaign in the Carolinas between January and March 1781. It was his heroics in the South that helped drive Cornwallis to take his fateful step into Virginia, and to his doom. Had it not been for Greene, it is difficult to envision a pivotal allied victory on the scale of Yorktown in 1781, and without Yorktown the war would have had a different ending, possibly one that did not include American independence.

Was American independence inevitable?

Chatham and Burke knew how independence could be avoided, but it involved surrendering much of Parliament’s power over the colonists. Burke also glimpsed the possibility of using proffered concessions to play on the divisions in the Continental Congress, which included many delegates who opposed a break with Britain. Burke’s notion might have worked. But from the beginning the great majority in Parliament thought that in a worst case scenario the use of force would bring the colonists to heel. Given the political realities of the day, war appears to have been virtually inevitable. Even so, independence very likely would have been prevented had Britain had an adequate number of troops in America in April 1775 or a capable general to lead the campaign for New York in 1776, someone like Earl Cornwallis.

A version of this Q&A first appeared on the Journal of the American Revolution.

John Ferling is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of West Georgia. He is a leading authority on late 18th and early 19th century American history. His latest book, Jefferson and Hamilton: The Rivalry that Forged a Nation, was published in October 2013. He is the author of many books, including Independence, The Ascent of George Washington, Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution, John Adams: A Life, and A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. He lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Q&A with John Ferling on the American Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 7/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Literature,

American Revolution,

Language,

America,

Secrets,

fireworks,

propaganda,

fourth of july,

rhetorical,

american literature,

common sense,

Rhetoric,

Humanities,

paine’s,

russ,

*Featured,

Rhetoric & Quotations,

colonial propaganda,

Leaks,

Propaganda 1776,

Revolutionary Communications,

Russ Castronovo,

Tom Paine,

castronovo,

freneau,

pamphlet,

Add a tag

By Russ Castronovo

Ever since 4 July 1777 when citizens of Philadelphia celebrated the first anniversary of American independence with a fireworks display, the “rockets’ red glare” has lent a military tinge to this national holiday. But the explosive aspect of the patriots’ resistance was the incendiary propaganda that they spread across the thirteen colonies.

Sam Adams understood the need for a lively barrage of public relations and spin. “We cannot make Events; Our Business is merely to improve them,” he said. Exaggeration was just one of the tricks in the rhetorical arsenal that rebel publicists used to “improve” events. Their satires, lampoons, and exposés amounted to a guerilla war—waged in print—against the Crown.

While Independence Day is about commemorating the “self-evident truths” of the Declaration of Independence, the path toward separation from England relied on a steady stream of lies, rumor, and accusation. As Philip Freneau, the foremost poet-propagandist of the Revolution put it, if an American “prints some lies, his lies excuse” because the important consideration, indeed perhaps the final consideration, was not veracity but the dissemination of inflammatory material.

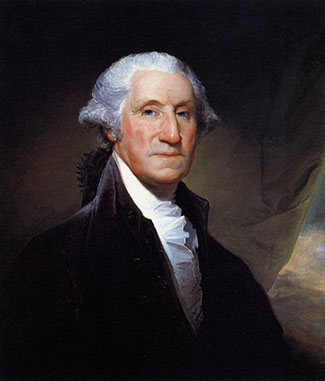

In place of measured discourse and rational debate, the pyrotechnics of the moment suited “the American crisis”—to invoke the title of Tom Paine’s follow-up to Common Sense—that left little time for polite expression or logical proofs. Propaganda requires speed, not reflection.

Writing became a rushed job. Pamphlets such as Tom Paine’s had an intentionally short fuse. Common Sense says little that’s new about natural rights or government. But what was innovative was the popular rhetorical strategy Paine used to convey those ideas. “As well can the lover forgive the ravisher of his mistress, as the continent forgive the murders of Britain,” he wrote, playing upon the sensational language found in popular seduction novels of the day.

The tenor of patriotic discourse regularly ran toward ribald phrasing. When composing newspaper verses about King George, Freneau took particular delight in rhyming “despot” with “pisspot.” Hardly the lofty stuff associated with reason and powdered wigs, this language better evokes the juvenile humor of The Daily Show.

The skyrockets that will be “bursting in air” this Fourth of July are a vivid reminder of the rhetorical fireworks that galvanized support for the colonists’ bid for independence. The spread of political ideas, whether in a yellowing pamphlet or on Comedy Central, remains a vital part of our national heritage.

Russ Castronovo teaches English and American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His most recent book is Propaganda 1776: Secrets, Leaks, and Revolutionary Communications.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Rhetorical fireworks for the Fourth of July appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Daniella Frangione,

on 7/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

american history,

American Revolution,

America,

Multimedia,

map,

kennedy,

frances,

independence day,

revolution,

sites,

interactive map,

cornfields,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

bunker hill,

The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook,

Valley Forge national historical park,

Frances H. Kennedy,

guidebook,

1768,

fraunces,

Add a tag

By Frances H. Kennedy

From the rocky coast of Maine to the shores of northern Florida to the cornfields of Indiana, there are hundreds of sites and landmarks in the eastern United States that are connected to the American Revolution. Some of these sites, such as Bunker Hill and Valley Forge, are better known, and others are more obscure, but all are integral to learning about where and how American independence was fought for, and eventually secured. Beginning with the Boston Common, first occupied by British troops in 1768, and closing with Fraunces Tavern in New York, where George Washington bid farewell to his officers on 4 December 1783, this map plots the locations of these sites and uses The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook to explain why they were important.

Frances H. Kennedy is a conservationist and historian. Her books include The Civil War Battlefield Guide, American Indian Places, and, most recently, The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mapping the American Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

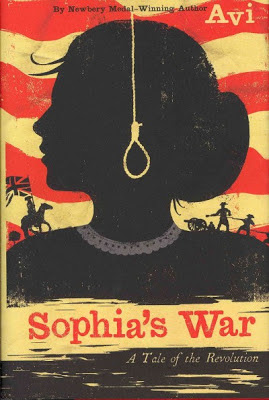

Avi has always been a favorite in our house and his latest book,

Sophia's War, is another addition to his

oeuvre of historical fiction that doesn't fail to satisfy. This time Avi takes the reader back to the American Revolution.

For 12 year old Sophia Calderwood, the revolutionary war is personal. Forced to flee with her mother and father when the British attack and seize lower Manhattan, on her return, Sophia and her mother witness, first, the hanging of Nathan Hale by the British for being a spy and second, the burnt remains of part of their lower New York settlement. Fortunately, the Calderwood house, though ransacked, is still standing.

Sophia's father had thought it wise to remain at a friend's house in northern Manhattan, but he soon shows up at home with a gunshot in him arm. It is decided that he will remain sequestered at home for now, since he is a known patriot and needs to recover. As for Sophia's brother William, a soldier fighting under General Washington, there has been no news of him for a while.

On top of all this, with the British now in charge, the Calderwoods are forced to billet a soldier. Lieutenant John André, handsome, cultured and kind, arrives at their door and Sophia is immediately taken in by his attention and many charms.

"In short, having never met so well bred and civilized a man as John André, I was greatly flattered by the attention. Indeed, I was nothing less than enthralled." (pg 56)

When Sophia lets slip to John André the her brother is a patriot, he lets her know that he will keep the information to himself, and that he will do whatever he can to help her family. So naturally, when Sophia discovers her brother seriously ill and starving in one of the British prisons known for their deplorable conditions, she is sure John André will help him.

The news that John André has been ordered to go to Staten Island immediately, prompts the Calderwoods to ask if he will help William. When Sophia confronts him about this, he tells her he cannot do anything, that his honor as a British officer is the most important thing in the world to him. But when Sophia reminds him that he had promised that, if needed, he would anything he could for her, he responds that a promise to a 12 year old is not like a pledge to a lady, and that she is not yet a lady.

Shaken to her core by this, Sophia vows to save William.

Fast forward to 1780, the war is still being fought. Sophia is now 15, working in a print shop to help her family out. There, because she can read, she is recruited as a spy for the Americans. Placed in the home of British General Clinton as a housemaid, she is asked to report any information she finds. But just as she discovers a plot of treasonous proportions involving an American general and her old friends John André, the person she reports to has disappeared for safety reasons.

What to do with all this information? Here is Sophia's opportunity to get revenge on John André for failing to help William by exposing the plot she has uncovered. Can a young 15 year old succeed against all odds and possibly change the tide of the war?

Sophia's War was an exciting book to read. Avi has taken a real event of the American Revolution that has many aspects to it that have never been explained and offers a cogent explanation. And why not? This is what historical fiction is all about. All the places and events, as well as most of the characters in

Sophia's War are real and you will probably recognize them from history lessons. It is told in the voice of self-conscious narrator Sophia, who directly addresses her readers in several places, making it sound plausible, while at the same time reminding us she is a fiction.

I thought this was one of Avi's best novels and I have loved all of them. My one reservation about

Sophia's War was the revenge aspect of her motivation. But, of course, in the end, there is much to learn from Sophia's motivations. Do read this novel is you enjoy good historical fiction.

This book is recommended for readers age 10+

This book was borrowed from Webster Branch of the NYPL

Simon & Schuster offer a reading guide for

Sophia's War including Common Core Standards

here.

This is book 1 of my

2013 American Revolution Reading Challenge hosted by War Through the Generations.

This is book 3 of my

2013 Historical Fiction Reading Challenge hosted by Historical Tapestry

In January, in My John And Tom (Part 2), I shared a bit about what made Adams and Jefferson so different. In this third and final segment on Those Rebels, John and Tom, I wanted to share a bit about the themes that brought them together—and drive the narrative: commitment and compromise.

The whole time I’ve worked on the book, our current Congress has been…stalled. (OK, I must admit I debated which word to use here—there are so many to choose from! I read recently that the majority of Americans would prefer to have the current members of Congress replaced by names drawn randomly from the phone book.)

The state of today’s Congress is the perfect backdrop to appreciate all that the Continental Congress achieved.

They started in 1774—with nothing.

They had to decide everything. How would voting take place. Would voting be based on population or would each colony have one vote?

And that was just the start. In addition to the hours spent debating in Congress, there was all the committee work. In June of 1776, while Tom was busy writing the Declaration—in the hopes that Congress would vote yea—Adams himself was serving on 26 committees, prompting him to write to a friend, “I am weary, thoroughly weary.” Among his many duties, he chaired the Board of War—for while America had not yet declared independence, Americans under General George Washington were already fighting British troops.

This sense of commitment was epitomized by what Adams called “the greatest debate of all”—the life-or-death decision that Congress had to make. And I mean that literally—when the members of Congress voted for independence, they committed treason. If America had lost the Revolutionary War, the British could have hanged them all.

The men of the Continental Congress had such commitment to their cause that they were willing to die for it.

And yet, they engaged in this life-or-death debate in the spirit of compromise.

Sure, they didn’t have the two-party system with have now—there weren’t Democrats and Republicans back then.

But the delegates came from all over the colonies, and each colony had its own concerns. A lot of the delegates had never even met when they first arrived in Philadelphia. And yet, when it came time to decide the biggest questions, they set aside regional concerns and sought out compromises to answer those questions—for the good of the whole.

Those Rebels, John and Tom

Those Rebels, John and Tom is an example of when Congress worked. It’s a timely reminder of how our government can and should work: not perfectly, not always easily, but always with our elected officials working together to move the country forward.

Commitment. Compromise. These are the themes of

Those Rebels, John and Tom. (PS. A shout-out to

Edwin Fotheringham, the illustrator of the book--aren't the illustrations great?!)

I was all set to post the third installment of my FoundingFathersPalooza—an exploration into how I conceived, researched, and wrote Those Rebels, John and Tom, my book about Adams and Jefferson. And I’ll post the final installment next month.

But something wonderful happened a few days ago that fits in so nicely, I couldn’t resist talking about it. You see, in a couple of weeks, I get to meet John and Tom.

In person.

I’ll be participating in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum’s “Presidents’ Day Family Festival” at the JFK Library in Boston, on February 21st.

And John and Tom are going to be there!

OK, technically, John Adams will be played by Thomas Macy and Thomas Jefferson will be played by Bill Barker – but take a look at the links. Don’t they look fabulous?! Both men are real history buffs and I know will do Adams and Jefferson proud.

We’ve been doing a bit of emailing, setting things up. Under the signature line for Thomas Macy’s emails are the quotes:

"Querulous, bald, blind, crippled, toothless Adams."

- Benjamin Franklin Bache

"I'm not crippled." - John Adams

And Bill Barker signs his emails:

Yr' hm'bl sr'vt,

Thos. Jefferson

I think this is going to be fun…

I am geeky excited. For someone who spent over a year working on the book, this is the next best thing to a time machine.

If you will be in Boston on Feb 21st, please join us, won’t you?

The Notorious Benedict Arnold: A True Story of Adventure, Heroism, and Treachery Steve Sheinkin

The Notorious Benedict Arnold: A True Story of Adventure, Heroism, and Treachery Steve Sheinkin

I think that Sheinkin gets nominated every year, and I know he’s made it through to the short list at least once. There’s a reason why-- he’s just that good. Sheinkin has a way of telling a story, even one you think you’ve heard before and making it completely riveting. In this book he takes on Benedict Arnold, American hero and traitor. It’s a rip-roaring yarn of fierce battles, crazy stunts, and incredible bravery that then goes completely wrong when Arnold does the unthinkable. Although we’re still unsure as to WHY he did it, we get a much more complete picture of the man than we usually do. Sheinkin can really bring history alive.

I hope he takes on Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys soon!

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

I thought I’d do something a little different for the next few months, and spend a bit more time talking about a single project: where I got the idea, how I developed it, and what I hoped the story would accomplish. A beginning-middle-end, if you will.

It wasn’t hard to choose the topic, as my latest book is a story I’ve been waiting most of my life to tell.

So today, I’m beginning the first of a three-part discussion of my latest book. But first, let me introduce my dear friends, John and Tom.

I was first drawn to the story of Adams and Jefferson because I grew up in the suburbs of Washington, DC. My father worked at the State Department, and so I think I was more aware of government than a kid living somewhere else might have been. I went in to DC and saw places like the Capitol and the National Mall pretty often.

I turned sixteen the summer of the country’s bicentennial, and I remember going downtown: it seemed like there were a gazillion tourists and even more of those sidewalk stands selling little American flags and patriotic t-shirts.

But even before then, I was tuned in to celebrating America’s independence, and that was because my mom and dad were big musical theater buffs. They had a whole cabinet full of Broadway recordings, and they listened to them almost every night. The musical “1776” was one of their favorites.

“1776” is the often funny and often quite moving story of the Continental Congress as they grappled with the enormous question of whether to remain a British colony or to declare independence—committing treason in the process.

The musical premiered on Broadway in 1969, and I think my parents must have bought the record shortly thereafter—when I was about ten years old. Many nights at bedtime *it* was the album I’d ask my dad to put on in the living room downstairs, so I could listen to it upstairs. I fell asleep listening to John urging Congress to “Vote YES” and to Tom wooing his wife on the violin.

I fell in love with the musical “1776.” It was my first glimpse that history could be just as exciting and engaging as any novel or movie.

So, in a sense, I grew up with John and Tom, and it’s not surprising that one day I would tell *my* version of their lives:

Those Rebels, John and Tom.

Next month, I share a bit about researching and writing the book.

Recommended for ages 9-14.This new release from Chicago Review Press about Thomas Jefferson, one of the most venerated of our founding fathers, is a great addition to any school or public library, as well as ideally suited for use by home schoolers. Although many biographies of Jefferson are available for young people, this one is unique in including a variety of hands-on activities to enhance learning, from how to organize your library like Jefferson, how to observe the weather, grow a plant from a cutting, or paint a buffalo robe. Although I did not try any of the activities, they include copious instructions, and are well suited for upper elementary and/or middle school students.

Organized chronologically, this book begins with some background on Jefferson's father, Peter, and his wife Jane. Thomas was the first of their eight children, and showed himself to have a quick mind from his earliest childhood. Jefferson went on to be a brilliant college student, often studying 15 hours a day (and without a tiger mother!), and then studied law. We learn about Jefferson's immersion in radical politics, his family life, and his drafting of the Declaration of Independence. Later chapters explore his presidency and his founding of the University of Virginia, as well as recounting the incredible story of his death on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence--the same day as his friend and rival, John Adams, also breathed his last.

Miller's volume is clearly written, and provides a fascinating look at this complex individual and his wide range of accomplishments and interests. I particularly appreciated that she does not shirk from analyzing Jefferson's many contradictions, which she summarizes as follows: "A man who believed in frugal government yet lived his own life burdened by debt. A man who hated kings and privileged nobles yet lived as an aristocrat himself. A man who believed passionately in freedom and liberty yet owned slaves who toiled for his comfort."

It is the last of these contradictions which is most difficult for us in the 21st century to come to terms with. Although Jefferson recognized the evils of slavery and even condemned slavery in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence, these remarks were removed in one of 86 changes made by Congress. Slavery, though, was deeply engrained in Jefferson's consciousness; he grew up in a slave-owning household, and inherited his first slaves when he turned 21. Miller includes in her book an advertisement Jefferson placed to recover a runaway slave, describes what is known of his relationship with Sally Hemmings, including discussing the many children she bore him (a new historical fiction novel for young people,

Jefferson's Sons, by Kimberly Bradley, comes out in mid-September, and will be reviewed here at The Fourth Musketeer later this fall).

This volume is greatly enhanced by an abundant use of illustrations, including many full page reproductions of paintings, photographs, maps, and drawings. The large format of the book and generous use of white space make the text easy to follow, and the author makes good use of many sidebars for further explanations of different topics in Jefferson's life, from his slave Jupiter to the Hemming family to political explanations of events such as the Sedition Act.

Back matter includes plac

Recommended for ages 7-12. While there is no shortage of books available on Ben Franklin and his amazing life, Alan Schroeder’s new picture book biography, written in an unusual almanac format uniquely suited to Franklin’s encyclopedic interests, is an attractive addition to books available for elementary school aged children. Written by Schroeder, author of other notable picture book biographies such as Minty: A Story of Young Harriet Tubman, and illustrated by New Yorker cartoonist and children’s book illustrator John O’Brien, this slim volume manages to pack a tremendous amount of information into the traditional 32-page picture book format. Each letter of the alphabet is represented by fitting entries related to Franklin and his life and work. For example, A is for Almanac (a brief three paragraph entry explains the popularity of almanacs in Colonial America and how Franklin was responsible for the most popular almanac of all, Poor Richard’s Almanac), Abiah (the name of Franklin’s mother), Apprentice (Franklin apprenticed in his brother’s printing shop), and Armonica (a musical instrument invented by Franklin). Franklin’s witty sayings, many of which remain popular today, appear on small banners in the detailed ink and watercolor illustrations.

0 Comments on Book Review: Ben Franklin: His Wit and Wisdom from A to Z, by Alan Schroeder (Holiday House, 2011) as of 1/1/1900

It's

Nonfiction Monday and I'm back from my vacation to Boston, a wonderful city which lays claim to the title of Birthplace of America. The role of Boston in the American Revolution cannot be denied, nor can the contributions of Alexander Hamilton, scholar, soldier, politician and statesman.

Frtiz, Jean. 2011.

Alexander Hamilton: The Outsider. New York: Putnam.

In

Alexander Hamilton: The Outsider, Jean Fritz follows a theme that ran through all aspects of Hamilton's life - that of outsider. Born on the island of St. Kitts in the West Indies, Hamilton was often accused of being an interloper in Revolutionary American politics. Once committed to the ideal of a free and independent America, however, his "outsider" status never dampened his enthusiasm for his country. Fritz recounts his many contributions to the revolutionary cause and to these United States.

Besides serving in the Revolutionary War, he was also an aide-de-camp to then General George Washington. He served as a New York delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He was the architect of the Bank of the United States and the nation's first Secretary of the Treasury. As a New Jerseyan, I knew that his life ended in Weehawken in the famous duel with Aaron Burr, but I did not know that he founded the city of Paterson. He was convinced that American should and would be more than an agrarian society. He chose Paterson because its large waterfall could be used to generate electricity for business. (In 2009,

Paterson's Great Falls became a National Park Historic District)

In short, using her customary exactitude, Fritz tells a complete story of a complex man, using only facts and period quotations in this small, slim, 144-page volume. Archaic language ("poltroon") or long-abandoned customs (anonymous leaflet writing) are explained fully in the author's Notes. Historical reproductions (credited) are scattered throughout. A Bibliography and extensive Index complete the book.

This would make an excellent choice for a school biography report, much better than the formulaic series that students often choose.

The United States Treasury website features a page on Alexander Hamilton, the nation's first Secretary of the Treasury, and architect of the National Bank and the US Mint.Just an aside - Jean Fritz is 95 years old! How wonderful that she's still working and producing great children's books.

Today's Nonfiction Monday roundup is at

Telling the Kids the Truth: Writing Nonfiction for Children. Please

By:

Susan E. Goodman,

on 3/14/2011

Blog:

I.N.K.: Interesting Non fiction for Kids

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

nonfiction,

writing,

American Revolution,

2008 titles,

Susan E. Goodman,

US History,

Deborah Heiligman,

finding the truth,

climate science,

Add a tag

In my somewhat new Monday slot, more of my posts fall on holidays (duh!) and I have just let them pass. Last month, for example, Valentine’s Day came and went, but my heart wasn't in it.

Today, however, I’d like to celebrate this week’s unofficial holiday that, in my opinion, deserves to become official--the onset of Daylight Saving Time (DST). What an emotionally lifting gift—especially to New Englanders who have been battling the suicidal impulses that accompany a 4:30 sunset. For months we have tried to keep our spirits up as the light inched back a minute at a time. Then PRESTO CHANGO! In just one day, arbitrary magic multiplies the jump times 60. We get a whole new hour of light—and life becomes brighter in every way. If only Zoloft worked so well.

Today, however, I’d like to celebrate this week’s unofficial holiday that, in my opinion, deserves to become official--the onset of Daylight Saving Time (DST). What an emotionally lifting gift—especially to New Englanders who have been battling the suicidal impulses that accompany a 4:30 sunset. For months we have tried to keep our spirits up as the light inched back a minute at a time. Then PRESTO CHANGO! In just one day, arbitrary magic multiplies the jump times 60. We get a whole new hour of light—and life becomes brighter in every way. If only Zoloft worked so well.

As nonfiction writers we are obligated to tell the truth and nothing but the truth, right? What about the whole truth, though? In this case, I would have to admit that DST causes increased danger of traffic and pedestrian accidents during its first week because of sleep cycle disruption. It was never created to help the farmers or reinstated more recently to save energy. In fact, farmers hate it and many experts believe it increases energy costs: electricity for air conditioning and over $100 million a year for the airlines.

Why did this idea gain purchase? Some British golfer in 1907 realized that if one hour of sunlight was switched from the sunrise side to sunset, he’d have time to get to the back nine. In fact, when the 1986 Congress debated the issue of extending it into March, the golf lobby went to town. According to Michael Downing, author of Spring Forward: The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time, the golf industry estimated the extension of DST would increase their revenues by 400 million 1986 dollars, the barbecue industry over $100 million. In other words, if you give Americans the chance to go outside at any time, they will spend money.

Why did this idea gain purchase? Some British golfer in 1907 realized that if one hour of sunlight was switched from the sunrise side to sunset, he’d have time to get to the back nine. In fact, when the 1986 Congress debated the issue of extending it into March, the golf lobby went to town. According to Michael Downing, author of Spring Forward: The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time, the golf industry estimated the extension of DST would increase their revenues by 400 million 1986 dollars, the barbecue industry over $100 million. In other words, if you give Americans the chance to go outside at any time, they will spend money.

Telling the whole truth about DST is not a horror. An ironic example of one of America’s worst traits, perhaps, but not a deal-killer. In the unlikely event that I ever wrote a book about DST, I’d “out” its origins with relish.

But what about other times, when telling the whole truth in our books for younger children is a lot more painful? Then how far do we go? I just attended a conference on sustainable energy this week where everyone had already accepted the devastating long range consequences of climate change as inevitable. Nobody was talking about getting better gas mileage or "clean coal." The focus was on how to think about reconfiguring communities in the Brave New World. I'm not considering a book about this subject either; but how do you give kids hope and this kind of information at the same time?

When I wrote See How They Run: Campaign Dreams, Election Schemes, and the Race to the White Hous

When I wrote See How They Run: Campaign Dreams, Election Schemes, and the Race to the White Hous

Murphy, Jim.2010.

The Crossing: How George Washington Saved the American Revolution. New York: Scholastic.

The brave young men who first enlisted as soldiers under General George Washington's command were promised

a few happy years in viewing the different parts of this beautiful continent, in the honourable and truly reputable character of a soldier, after which, he may, if he pleases return home to his friends, with his pockets FULL of money and his head COVERED with laurels.

Of course, anyone familiar with the Revolution knows that nothing could have been further from the truth, which is why the choice of this 1775 recruiting poster makes such an excellent place to begin

The Crossing: How George Washington Saved the American Revolution. After the victories at Lexington and Concord, Congress and soldiers were feeling brave and confident. It seemed that only George Washington understood the gravity of the situation and the enormity of the task ahead.

Jim Murphy's latest book is not a chronicle of the American Revolution, but rather a close look at the period between June 15, 1775, when Washington was appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental army, and January 3, 1777, when the Continental army defeated the British troops at Princeton, following the famous

victory at Trenton on December 26, 1777. This was, Murphy contends, the most crucial period in the American Revolution, the period when the very survival of the nation hung in the balance.In seven chronological chapters, Murphy carefully recounts the strategy, battles, and general mood of the soldiers and citizens during this period. Maps, period artwork and quotations help to set the desperate mood of the

times. At one point, after George Washington's "humiliating retreat through New Jersey,"

even a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Richard Stockton, gave "his word of honor that he would not meddle in ... American affairs" and swore allegiance to King George III.

(Here I am left to wonder why one of New Jersey's colleges is named after Mr. Stockton, though he apparently did, at a later date, again swear allegiance to the United States.)During a retreat from Fort Lee in November of 1776, just barely ahead of advancing British troops, Murphy writes that Washington's

desperate soldiers abandoned cooking kettles, muskets, ammunition pouches, and unnecessary clothing as they staggered along. A New Jersey citizen recalled that these soldiers "looked ragged, some without a shoe to their feet, and most of them wrapped in their blankets."

As always, Jim Murphy's book is thoroughly researched, highly engaging, and exhaustively indexed. A timeline, list of Revolutionary war sites, and notes and sources are also included.

As a New Jerseyan, an undergrad history major, and mother who has accompanied the annual 4th graders' class trip to Trenton, I am quite familiar with New Jersey's Revolutionary history, but still found

The Crossing to be enlightening and engrossing. Particularly interesting to me is the lengthy explanation following the final chapter, of the famously inaccurate painting, "Washington Crossing the Delaware." Murphy has g

Recommended for ages 10 and up.

I was so excited to finally get my hands on

Forge, the sequel to

Laurie Halse Anderson's acclaimed

Chains, which was a National Book Award finalist and the winner of the Scott O'Dell Award for Historical Fiction. About the only thing I didn't relish about

Chains was the ending, which left the reader with a nail-biting cliffhanger in what felt like the middle of the story.

If by some chance you missed

Chains, you'll want to read it before delving into this sequel--the second volume of a planned trilogy.

Chains, set at the beginning of the Revolutionary War, focuses on the story of Isabel, a 13-year old slave owned by a prominent New York City family who support the British. Isabel meets another slave, Curzon, with ties to the Patriots, and becomes a spy for the Patriot cause--with the hopes of obtaining her freedom.

In

Forge, the story begins where

Chains ends, with Isabel and Curzon escaping to freedom, but the focus of the story quickly changes from Isabel to Curzon. The two have separated again, with Isabel running away to try to find her sister and Curzon finding himself in the middle of the Battle of Saratoga, then enlisting in the Patriot army. The irony of a slave fighting for the freedom of others does not escape Curzon, who attempts to argue his case with his friend and fellow soldier Eben. Curzon questions whether bad laws deserve to be broken, but Eben is frustrated by Curzon's logic. "Two slaves running away from their rightful master," he says," is not the same as America wanting to be free of England. Not the same at all."

But when the army arrives at the winter encampment at Valley Forge, white and black soldiers alike are unprepared to deal with the conditions there: about 12,000 soldiers with no barracks, bitter cold, and no meat. The author begins each chapter with a quote from a contemporary source, many of which are increasingly desperate reports from General Washington to the Continental Congress on the need for supplies of all kinds, from food to shoes to clothing. Most days rations consisted of nothing but firecake, a mix of flour and water that tasted like ashes and dirt, and was "hard enough to break rat's teeth." Anderson so successfully evokes conditions at the camp that we groan along with the men at their terrible conditions. But the men manage to find a little humor in their situation..no food means "we've got nothing to fart with." A special treat for Christmas is a piece of chewy pigskin to chew on (I'm assuming like the pigs ears people buy now for our dogs).

Through all the hardship Curzon manages to keep secret that he is really an escaped slave, but he can't stop thinking about Isabel and what might have become of her. Fate is to bring them together again at Valley Forge. While General Washington and Baron von Steuben try to forge the raggedy American volunteers into real troops, Curzon and Isabel try to forge their way to a new relationship...are they more than friends or an ever-bickering brother-sister pair? And can they in turn forge their way to a life of freed

om

0 Comments on A Historical Thriller: Forge, by Laurie Halse Anderson (Atheneum Books, 2010) as of 1/1/1900

Dear John Adams, you've got a birthday coming up, on the 30th of this month, to be exact. On the 19th, by the old reckoning, set aside when you were not quite 18. It will be your 275th. Wait – let me imagine the glorious light of 275 candles, set into a spice cake, and the breath required to extinguish them. Make a wish, I'd hope you would, for this governing machine that you helped to invent, this ongoing experiment in participatory democracy. I'm imagining what an old Braintree lawyer/farmer/orator/public servant such as yourself would make of the republic for which you and your 'Dearest Friend,' – please pardon me the liberty for thus referring to Mrs. Adams – gave so much. I'm imagining what you'd look like now. I'm thinking of Sam Jaffe as the remarkably well-preserved High Lama in the 1937 Frank Capra film, Lost Horizon.

I doubt you'll read this, having other things to do in the Blue Beyond, but you might wish to know that, though there's no great stone monuments or temples to you in Washington, D. C., you've been the subject of many a heartfelt book, including a couple of mine. More about them later. I was introduced to you, your ebullience and stubborn earnestness in a fine work of historic fiction, Irving Stone's Those Who Love (1965; A book club sent it to my folks when I was 14.) and in Catherine Drinker Bowen's 1950 biography, John Adams and the American Revolution, found in a used bookstore. These as well as Jos. J. Ellis's The Passionate Sage (1993) and David McCullough's John Adams (2001), but how about books for young citizens?

There's John and Abigail Adams:An American Love Story, by Judith St. George (2001); certainly Abigail Adams: Witness to a Revolution, by my friend Natalie S. Bober (1998); and this year's handsome Picture Book of John and Abigail Adams, written by David A. Adler, illus. by Michael S. Adler. But allow me to write a bit about how I went about writing and illustrating the pair of books I did about the Adamses.

In 1994 Bradbury Press published Young John Quincy (Out of print it's been for years, the title being unclear and the world being unfair, as you well know.) It was followed nine years later by The Revolutionary John Adams (National Geographic). The happy problem, in the latter, was distilling your long adventurous life into 48 pages. I pored over said bios along with Esther Forbes' book about Paul Revere - excellent for the feel of your time and place. Not being able to go to your time, I did manage to go to your place, your house, which still sits beside your folks' house, in which you were born.

They were farmhouses in the 1700s. Folks walked or rode their horses or jostled along the country road between Boston and Plymouth. Now they're surrounded by every sort of business, jammed side by side in modern Quincy,

Paulsen, Gary. 2010.

Woods Runner. New York: Wendy Lamb.

At only thirteen years old, Samuel is already a man in some ways. Born on the frontier, he is at home in the woods; hunting, tracking and providing for his family. His parents have taught him to read, to be curious, to enjoy the hard work and simplicity of the frontier, but at heart, they are city-born, content to live at the edge of the great woods. Samuel, though, is perhaps even more at home in the woods than in his family's modest home.

So it is that Samuel is away hunting bear when the war comes to Western Pennsylvania. Carefully deciphering the tracks and signs near the scorched earth of what was once their settlement, Samuel knows that his parents have been taken captive by British Redcoats and their Native allies. Others from the settlement were not so lucky. After burying the dead, Samuel sets out to find his parents - traveling eastward to the Redcoats stronghold, New York.

Like a

Cold Mountain for teens and young adults,

Woods Runner doesn’t recount the battles of war , but rather, its impact on civilian life. Samuel, his parents, and his traveling companions do not fight in the war, but neither can they escape it.

"It is the way of it," Abner put in from the darkness, "of war. Some get, some don't, some live, some ... don't. It's the way of it.

"It's bad."

"Yes. It is. But it is our lot now, and we must live it." Abner sighed. "The best we know how.”

A historical tale of action, suspense, determination and survival. Single page entries of historical facts (ammunition, orphans, communication, etc.) separate the chapters and add background and perspective to this short, gripping story. History repeats itself every day in some location in the world. It's good to remind ourselves sometimes of war's less visible consequences. Highly recommended for grades 6 and up.

Read an excerpt from Woods Runner.Bookpage has a g

reat interview with Gary Paulsen.Woods Runner, Three Rivers Rising, One Crazy Summer, The Keening, Countdown ... this has been a great year for historical fiction. I can’t wait to see what wins the

Scott O’Dell Award. It’s hard for me to pick a favorite.

I nominated this book for the

Cybils (Children's and Young Adult Bloggers' Literary Awards) in the Young Adult category. Anyone can nominate books until October 15th. Just be sure to read the

nomination rules first.

Share |

0 Comments on Woods Runner as of 1/1/1900

For ages 10 and up.Ann Rinaldi is one of our most prolific and well-loved writers of historical fiction for young people, particularly well-known for stories set during the American Revolution and the Civil War. That said, I was disappointed with her newest novel, published in May, which centers around several generations of women in the family of General Nathaniel Greene, second in command to George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

Even the cover is disappointing, with its sad-faced model that doesn't seem to fit at all with the themes that emerge in the story (compared to the stunning YA covers that have been coming out lately, what teenager is going to pick this one up?) The story is told in two parts; the first part is narrated by Katy Littlefield, who is 10 years old when our story starts. She is sent to live with her worldly Aunt Catharine, whose husband is a prominent patriot. Her aunt is a notorious flirt and good friends (or perhaps more?) with Benjamin Franklin. Her aunt is supposed to teach her how to be a "lady," with lessons such as this:

You should know this, Caty Littlefield...we women have the right to flirt. If it is kept a harmless pastime. Men expect it from us. Done properly, it gives us power, and Lord knows we have litle of that...But it must be learned to be done properly.

When Katy grows up, she marries a cousin of Uncle Greene, Nathaniel, 12 years older than she is. War breaks out soon after their marriage. Her husband is quickly promoted to brigadier general, and she goes with him, as did Martha Washington, to live at Valley Forge, where she entertains all the gentlemen with her lively spirits, and becomes a "belle of the camp."

Rinaldi then cuts off this story and switches narrators to Caty's daughter, Cornelia, some years later on the family plantation in Georgia. Cornelia is concerned with her mother's reputation when she witnesses her exchanging kisses with their schoolteacher, but Cornelia's problems escalate when her nasty older sister tells her that Nathaniel Greene is not really her father, but rather that her father was a lover of her mother's. Cornelia becomes obsessed with finding out the truth about her parentage.

This would have been a more appealing novel if Rinaldi had stuck with the first part of the narrative, perhaps enlarging on the section in which the young married Greenes are at Valley Forge. In the second half of the novel, the character of Caty suddenly changes, without explanation, to a mean-spirited flirt who can be cruel to her children and disrespectful to her husband by her actions, which to my view go beyond most people's definition of flirting. While some of Rinaldi's fans may enjoy this book, it definitely was not one of her best.

By: Rebecca Ford,

on 4/23/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Film,

American History,

American Revolution,

History Channel,

A-Featured,

textbook,

Leisure,

independance,

colonies,

Joy Hakim,

A History of US,

America: The Story of Us,

Early America,

hakim,

1791,

treaty,

ticonderoga,

hakim’s,

volumes,

colonist,

Add a tag

Julio Torres, Intern

A History of US is the James Michener Prize-winning collection of books written by Joy Hakim, a former teacher and editor. The series tells the story of the nation through its ten volumes. For the next six weeks, starting Sunday, the History Channel will air their ambitious chronological series, America: The Story of Us.

Since A History of US and America: The Story of Us, follow the same timeline we thought it would be fun to share some of American history’s lesser-know facts found along the margins of the books. Make your way through the nation’s history as we enlighten you with facts and challenge you with trivia questions inspired Hakim’s volumes.

First up, trivia questions from books 2 and 3, Making Thirteen Colonies and From Colonies to Country, corresponding to the History Channel’s first week of the series (premiering April 25th) dedicated to the colonies and the Revolutionary war. Don’t be discouraged if most of these feel obscure, chances are they were bonus questions back in Middle School. The answers are at the bottom of the post. Be sure to check back in the coming weeks for more fun content related to our nation’s great history. Read an original post by Hakim here.

What state was its own nation from 1777 to 1791 and became the first state to outlaw slavery?

Which Shakespeare play was inspired by the wreck of the colonist ship, the Sea Venture?

What state name means “at the big hill” in Algonquian?

Which treaty officially ended the French and Indian War?

What famous, brave soldier switched sides from the Patriots to the British in 1780? (He captured Fort Ticonderoga)

Answers: Vermont, The Tempest, Massachusetts, The Treaty of Paris, Benedict Arnold

By: Lana,

on 3/4/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Blogs,

American History,

American Revolution,

Iraq,

A-Featured,

1770,

As If An Enemy's Country,

Boston Massacre,

March 5,

occupation,

Richard Archer,

Add a tag

By Lana Goldsmith, Intern

Richard Archer is Professor of History Emeritus at Whittier College. Current events in Iraq have caused him to hark back to an earlier time in American history when ours was the occupied country. In this post, he uses an excerpt from his book, As If an Enemy’s Country, to discuss the Boston Massacre and his theory on the soldiers’ actual intentions. The Boston Massacre occurred on the night of March 5, 1770, read more about it here.

One of the joys of historical research is the unexpected discovery. Sometimes a new understanding of seemingly familiar material comes from events in our own lives. In 2003, for example, when I was well into studying why Boston was in the forefront of the movement toward the American Revolution, the United States went to war with Iraq. I immediately was sensitized to the importance of an occupation and old documents suddenly had new meanings.

A similar experience came while I was investigating the Boston Massacre. Previous accounts gave the impression that the soldiers had mindlessly fired their weapons. Whether there was an order to fire or not (I conclude not), the standard story simply stated that the soldiers discharged their muskets and five people died and another six were wounded. Much to my surprise as I read depositions and trial testimonies, several witnesses charged that some soldiers fired at specific individuals. The evidence isn’t definitive, but it certainly opens the possibility of murder, as the following excerpt from As If An Enemy’s Country demonstrates:

There looms the possibility that some of the soldiers killed or attempted to kill particular people deliberately. Sailors and soldiers had fought with each other nearly from the first day of the occupation, and Friday’s ropewalk fray still was fresh in the minds of soldiers of the 29th Regiment. Even in the moonlight, the sailors’ attire distinguished them from the rest of the population. Two of the five men who died in the massacre were sailors, and one was a ropemaker who had fought with British troops on March 2. Another sailor was among the six who were wounded but recovered. It is equally possible that the victims were shot randomly. After all, the proportion of sailors and the ropemaker who died approximated the proportion of sailors and ropemakers in the crowd. Most of those who were killed or wounded were shot from a distance where visibility, even with moonlight, was limited and the accuracy of muskets was imperfect.

The deaths of Attucks and Gray, however, require special attention. Both of those men stood in close proximity to the grenadiers, and they would have been recognized as a sailor and a ropemaker. The unusually tall, dark Crispus Attucks stood out still more, particularly at a distance of no more than fifteen feet. Two bullets, from one or two muskets, simultaneously struck him in the chest. Whether the responsible soldier or soldiers intended to kill him may never be known, but there can be little doubt that one or two aimed at him. Perhaps it is only a coincidence, but the only other victims who received two bullets were the sailors James Caldwell and Robert Patterson.

The evidence that Samuel Gray was intentionally killed is stronger still. In a deposition Charles Hobby claimed that one of the grenadiers ‘at the distance of about four or five yards, pointed his piece directly for the said Gray’s head and fired. Mr. Gray, after struggling, turned himself right round upon his heel and fell dead.’ Edward Gambett Langford, in his testimony at the soldiers’ trial, identified the shooter as Matthew Kilroy, one of the grenadiers fro

View Next 7 Posts

Those Rebels, John and Tom is an example of when Congress worked. It’s a timely reminder of how our government can and should work: not perfectly, not always easily, but always with our elected officials working together to move the country forward.

Those Rebels, John and Tom is an example of when Congress worked. It’s a timely reminder of how our government can and should work: not perfectly, not always easily, but always with our elected officials working together to move the country forward.

Lovely review! I loved your synopsis.

I think the revenge aspect is something kids thoroughly understand, and will feel as deserved, under the circumstances. But I also got the feeling that in the end, the revenge didn't seem to sit well with Sophia either.

Here is my review: http://www.inhabitingbooks.com/2012/10/sophias-war-tale-of-revolution-by-avi.html

Nice review, Megan. I am glad you nominated for a Cybil. It is such an interesting story and a great use of a historical event that had some missing pieces to it.

My kids and I bounced off _Fighting Ground_ (we thought the boy was super dumb, usually in ways that obviously pushed the plot forward), but I usually like Avi so maybe we'll give his American History a second chance.

I have a vague memory of another Sophie book about the American Revolution; she's a girl who also spies while working as a maid. I think she was African American. O History Expert, have you heard of this? It's probably more of an early chapter book, aimed maybe around 3rd grade?

I love books like this, especially ones that use real life people as characters. They have a way of bringing history to life and this sounds like a good one. Going on my list of books for my daughter when she's older! Great review, Alex.

Great review - really made me want to read it. And thanks as well for the link to the reading guide with common core standards - that was interesting!

So glad you're part of the comment challenge!

best,

Lee

I definitely think this is worth reading, even if one is not an Avi fan. I can't recall any other book about the American Revolution with a characterer named Sophia, but I have a vague recollection of a story similar to what you describe. The American Revolution really is my area of expertise, which is why I joined the reading challenge at War Through the Generations.

I agree and I am sure you and your daughter will like this when she is older. Avi has a great way of bringing his characters to life.

Thanks, Lee, this is my third year participating int ee comment challenge and I always find new blogs to read. Thanks for hosting it again with MotherREader.

I love the cover and Avi! I must read this one! It sounds great and then I can recommend it to my students during our HF unit. ;)

I usually notice the new books by Avi, but I hadn't heard of this one. It sounds like a great read - and what a gripping cover!

Glad you liked this one! I snagged it from the library to read for the challenge and hope to get to it before I have to bring it back. We'll get your review on WTTG soon.

Wow! This book sounds exciting! I love Avi and though I usually don't like books on war, this sounds like a must read!

Excellent review. You convinced me to read it. It's on my list. I like many of Avi's books, some more than others. Generally, he does a good job of taking a reader back in time and telling a compelling story.

Isn't Avi astounding? It seems he can bounce into any genre & really nail it. I imagine it's taken a whole heap of work on his part, but the books read as though it all comes naturally & effortlessly. Great review - thanks.

I love the cover of this, too and when you read the book, it takes on a double meaning - the hanging that Sophia witnessed and...Oop, I almost gave away too much.

It is excellent and I also thought the cover gripping. I'm not sure when this book came out, but it was 2012 and your year was pretty busy, as I recall.

Thanks, Anna. It's a quick read, mostly because it is so interesting. I really enjoyed it.

Ironically, I don't like war books that are about fighting the enemy, but this is more like a home front book to me, what life was life in NYC during the Revolutionary War and how it impacted Sophia made this book for me. Although the spying part was pretty exciting.

Thanks, Cora. I think Avi does a pretty decent job on historical fiction. I loved his two WW2 books that I read for this blog. I hope you enjoy Sophia's War.

Thanks, CS, I totally agree with you on how well Avi handles the various kinds of books he writes. He is very versatile, and this is not exception to his ability.

Alex, every single one of your reviews makes me want to the read the book in question, and this is no exception.

Holy man, if the book is even half as exciting as your review, it has to be good.

It's been quite awhile since I've read anything by Avi, but based on your review, this sounds like a good one. I'm adding it to my list! Great post!

I think this is an excellent post about an important topic. I had a roommate in college who talked about this all the time. He would really enjoy it. I am going to share with everyone your wonderful site.

Do I sound like a robot yet? Can you tell I am catching up on my blog reading?

Seriously, I do like Avi and I especially like the tone of the quote you included. Sounds so right for the time period.