I've just finished reading a wonderful blog by Penny Dolan over on The History Girls, about a series of connections that lead her from a randomly-chosen book from her shelves, right through a whole string of 19th century names, fictional characters and relationships, all linked by a wooden-legged chap called W.E. Henley. Which made me think of Charlotte Bronte. Recently, she's been my W.E. Henley.

It started with a Facebook post - which sent me to the Harvard Library online site where they have been working on restoring the tiny books Charlotte and Branwell Bronte made when they were children - which led to my own History Girl post Tiny Bronte Books.

(Please, if you go to have a look, scroll down to the bottom and watch the Brontesaurus video - you won't regret it.)

I'm in the midst of editing an anthology of East Perthshire writers called Place Settings and was delighted to read in one of the entries the author's interest in the Brontes, and how "... every night, the sisters paraded round the table reading aloud from their day's writings."

Then I got involved in a project run by 26, the writers' collective, in which writers were paired with design studios taking part in this year's London Design Show, and asked to write a response to one of their objects. I was given Dare Studio who were putting forward, among other lovely things, a new design - the Bronte Alcove.

The alcove is meant to be a private space within public places, blocking out the surrounding bustle and noise. Which made me think of bonnets. Which led me back to the internet, which led me, by way of images of hats, to the passage below, written by Elizabeth Gaskell on her visit to Charlotte at the parsonage:I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it.

Which led me to wonder ... my own practice has always been to try not to think about work when I'm courting sleep. And I have rarely, if ever walked round my table of an evening, reading aloud from my day's work. But have I been losing out here? Do you do as Charlotte did? I would be most interested to know.

Meantime, I wait for the next popping up of my very own W.E. Henley.

COMING: March, 2015

Guest post by K.M. Weiland

Ooh, bad guys. Where would our stories be without their spine-tingling, indignation-rousing, hatred-flaring charm? It’s a legit question. Because, without antagonists to get in our heroes’ way and cause conflict, we quite literally have no story.

So write yourself a warty-nosed, slimy-handed dude with a creepy laugh. No problemo, right? Bad guys aren’t nearly as complicated as good guys. Or are they? I would argue they’re more complicated, if only because they’re harder for most of us to understand (or maybe just admit we understand).

The best villains in literature are those who are just as dimensional and unexpected as your protagonists. They’re not simple black-and-white caricatures trying to lure puppies to the dark side by promising cookies. They’re real people. They might be our neighbors. Gasp! They might even be us!

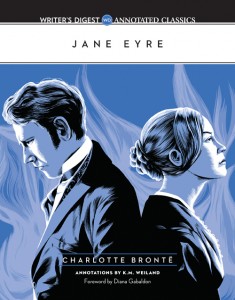

That raises some interesting possibilities, doesn’t it? It also helps us realize that villains can come in many different shapes and sizes. While studying Charlotte Brontë’s rightful classic Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic), I identified four major types of villain.

That raises some interesting possibilities, doesn’t it? It also helps us realize that villains can come in many different shapes and sizes. While studying Charlotte Brontë’s rightful classic Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic), I identified four major types of villain.

The Evil Villain: Mr. Brocklehurst

When we think of villains, this is the type we think of most often. He’s just nasty. He’s cruel, hypocritical, self-serving—and readers just want to punch him in the face. He may take the form of a mafia don, a dictator, a serial killer, or even something as comparatively “harmless” as an overbearing father.

In Jane Eyre, the evil villain manifests deliciously in the tyrannical Mr. Brocklehurst, the head of the horrible boarding school where Jane’s aunt disposes of her. Brocklehurst isn’t evil because he’s out killing, raping, or stealing. He’s evil because of his complete lack of compassion and his sadistic pleasure in his own power. When a young Jane dares to stand up to him, he subjects her to cruel punishment and lies about her to the rest of the school.

Even worse, he pretends he’s a pious benefactor. He has no idea he’s a cruel bum. He believes he and his school are saving these poor girls! Always remember that even the most evil villains will rarely recognize their own villainy. As far as they’re concerned, they’re the heroes of their own stories. Lucky for us, their hypocrisy only ups the ante and makes them more despicable.

The Insane Villain: Bertha Mason

Sometimes villains aren’t so much deliberately bad as psycho bad. They’re out of their heads, for whatever reason, and they may not even realize how horrifically their actions affect others. Psychos are always popular in horror stories for the simple fact that their near inhuman behavior makes them seem unstoppable. If they can’t understand the difference between right and wrong, what chance will your hero have of convincing them of the error of their ways—before it’s too late?

Perhaps the most notable antagonist in Jane Eyre is the one readers don’t even see for most of the book. She’s on stage for only a few scenes and mentioned outright in only a few others. But her presence powers the entire plot. [SPOILER] I am, of course, talking about Bertha, the mad wife of Jane’s employer and would-be husband Edward Rochester, whom he secretly keeps locked in the attic. [/SPOILER] The whole story might not even have happened had Bertha not been bonkers.

The insane villain is a force of nature. Although there will always be motivations for their behavior (even if they’re only chemical), they are people who aren’t behaving badly for sensible reasons. They can’t be rationalized with, and they won’t be moved by empathy for others. Their sheer otherness, coupled with their immovability, makes them one of the most fearsome and powerful types of villain.

The Envious Villain: Blanche Ingram

The envious villain is your garden-variety bad guy (or girl). These folks are a dime a dozen because their motivations and desires are ones almost all of us experience from time to time. Their envy, ego, and personal insecurity drives them to treat others badly for no other reason than spite (whether it’s petty or desperate).

Halfway through her story, Jane Eyre faces a formidable rival for Mr. Rochester’s love—the beautiful Blanche Ingram. Blanche is everything Jane isn’t (she’s the popular girl to Jane’s lunch-table outcast): gorgeous, rich, accomplished, and socially acceptable. On the surface, Blanche has no reason to fear or envy our plain-Jane protagonist. And yet, right from the start, she senses Jane as a threat to her marriage plans, and it immediately shows in her snide, condescending, and sometimes downright cruel behavior.

Envious villains are often those who, like Blanche, seem to have it all. But their glamour disguises deep personal insecurities. No one is ever a jerk for no reason. There’s always something (whether it’s a spoiled childhood or low self-esteem) that drives these most human of all villains. But don’t underestimate the power of their antagonism. Their envy can cause them to commit all sorts of crimes—everything from rudeness to murder.

The Ethical Villain: St. John Rivers

This is my personal favorite villain type—because he’s so darn scary. The ethical villain, like the envious villain, is less noticeable in his antagonism than are evil and insane baddies. This guy isn’t even a bad guy at all. He’s a very good guy. But he’s taken his goodness to the extreme. He’s on a crusade to save the rest of the world—either including or in spite of the protagonist—and heaven help anyone who gets in his way. He’s convinced the means absolutely justify his holy end.

Jane’s cousin St. John Rivers is a marvelous character. He is a man who is determined to live righteously and make his life count for some deeper purpose. He surrenders his own love for the village belle in order to go to India as a missionary. Doesn’t sound so bad, does it? And yet, his cold-hearted devotion to what he views as his duty, and his determination to make Jane adhere to those views, presents her with her single fiercest and most dangerous antagonist. St. John would never dream of harming Jane or committing a crime, but his fanaticism for his cause very nearly destroys her life.

The ethical villain is ethical. He conforms to most, if not all, of society’s moral norms. But somewhere along the line, those ethics fail to match up with the protagonist’s. That exact point is where he becomes an obstacle (and therefore an antagonist) to the hero. But he also offers us one of our richest opportunities for exploring moral gray areas and deep thematic questions. As such, he is arguably the most valuable villain type in your author’s toolbox.

The possibilities for antagonists are every bit as rich as they are for protagonists. Stop and take a second look at your story’s villain. Does he fit into one of the four categories we’ve discussed here? How can you take full advantage of that category’s opportunities for creating a compelling opponent? Or would your story benefit if you used a different kind of villain? Or maybe more than one kind side by side? The choices are endless!

–

K.M. Weiland

lives in make-believe worlds, talks to imaginary friends, and survives primarily on chocolate truffles and espresso. She is the IPPY and NIEA Award-winning and internationally published author of the Amazon bestsellers

Outlining Your Novel and

Structuring Your Novel. She writes historical and speculative fiction from her home in western Nebraska and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

Have you ever been asked the question, "If you could invite 12 people--living or dead--to dinner, who would they be?"

Have you ever been asked the question, "If you could invite 12 people--living or dead--to dinner, who would they be?"

Author Nava Atlas's latest book, The Literary Ladies' Guide to the Writing Life, is the literary version of that dinner party. Using their diaries, letters, memoirs, and interviews, Atlas has compiled writing advice from a dozen successful female writers. Her "dinner party" includes Louisa May Alcott, Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, Willa Cather, Edna Ferber, Madeleine L'Engle, L.M. Montgomery, Anaïs Nin, George Sand, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Edith Wharton, and Virginia Woolf.

Nava's own insightful commentary lifts the curtain on these women's lives and provides reassuring tips and advice on such subjects as dealing with rejection, money matters, and balancing family with the solitary writing process that will resonate with women writers in today's world. This inspirational book is punctuated with photographs, letters, drawings and other illustrations. It makes a splendid gift book for writers or yourself. Just view the book trailer (designed by the author herself!) below.

[If you're reading this in Feedburner e-mail and can't see the video below please visit www.LiteraryLadiesGuide.com or click on the blog title link.]

Book Giveaway Contest: If you'd like to win a copy of The Literary Ladies' Guide to the Writing Life, please leave a comment at the end of this post to be entered in random drawing. The giveaway contest closes this Thursday, March 24th at 11:59 PM, PST. We will announce the winner in the comments section of this post the following day, Friday March 25th. Good luck!

The Literary Ladies' Guide to the Writing Life by Nava Atlas

Published by Sellers Publishing (March 15, 2011) | Hardcover w/ Jacket | 192 pages | 130+ color/BW vintage photos | ISBN: 978-1-4162-0632-2

The book is available for purchase at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, Borders, Indie Bound, and at bookstores nation wide.

----- About the author:

----- About the author:

Nava Atlas is the author and illustrator of many well-known vegetarian and vegan cookbooks, including

2 Comments on Jane, April Lindner, last added: 1/15/2011

2 Comments on Jane, April Lindner, last added: 1/15/2011

This sounds like a book that would make the perfect gift for a friend...Wait, that means I would not be able to keep it! Forget about it being a gift. I'll try again.

This sounds like a book I would love to keep for myself!

I can't get enough books on writing in my life. I'm in!

I would love a copy of this book! But, just as important a question, what would you SERVE to the 12 people you'd have over for dinner? :)

A delightful interview and a book that sounds inspirational. I can only image the process, Nava, that it took to narrow down the offerings. I, too, would get caught in the research and spend all my time reading about more and more women. So many women inspire me! That's why i chose my motto of "Writing Strong Women."

I especially liked Nava's description of the challenge to crossover to a new genre and her courage in making the leap to nonfiction. The book seems very inspirational and I look forward to reading it.

great interview! Very inspiring — and I love the book trailer!

Sounds like a great read! Boy, if I had to choose 12 women, I would be hard-pressed to narrow it down...too many amazing women writing today, as well as in the past.

This sounds like a grat read for writers!

So enjoyed the background story to the book.

Really enjoyed reading this interview. What a great creative life Nava Atlas has!

Some family members have turned to veganism, so will definitely look to her books to learn how to cook for them - and me :)

The Literary Ladies' Guide to the Writing Life sounds like a book I would enjoy very much.

The act of writing is simple in and of itself, but the endless possibilities it offers are what makes it so compelling. It's a yielding art, conforming itself to whatever niche--large or small--we wish to give it in our lives.

I love this quote, it will find it's way onto the blog I share with three other literary geeks. :)

THX!

Toni

This book sounds so great! Nava-I liked when you said your editor told you to "turn up your voice." I recently had a friend tell me the same when I was writing a contest piece. I look forward to reading this book! Thanks WOW for sharing Nava with us!

Wow, what a Rennaissance Woman Nava is! Inspiring and intimidating at the same time. Hope this book gets lots of positive attention!

Definitely a must-buy book for me! (or win!) I loved this interview, too. I'll have to check out the rest of your tour for more!

How do you find time to research and write when you have so many other obligations. As a writer myself, I wish you every success with this new endeavor.

I would love to read what these masters have to say about writing!

I am so buying this book if I don't win a copy here. My home library is full of amazing books on writing. In fact, I can attribute my success as a full-time freelancer to the men and women whose books I have read. Can't wait to read it.

What an amazing story you have Nava. I admire all the strong, inspirational women writers you mentioned so much. Thank you, WOW, for introducing me to Nava.

What an interesting concept! I would love to read this.

Oh, how I would love to own this book! Thank you for leaving your kitchen and entering my office. Reading the lives of other authors inspires me. May you be blessed!

I'm interested in what meal you'd prepare for the 12 too!

This was a wonderful interview and the book sounds fantastic. I'd love to win a copy to give to one of my writing friends; I'm buying my own!

:) Congrats on the new book, Nava--and the the leap into different literary waters.

Just reading about this book was inspirational!

You hooked me, Nava! You selected all women I have enjoyed reading over and over again. Now I can learn more about their lives. I look forward to reading your book and giving copies away to my writer friends as gifts.

My mother, who is in her 80s, has always been a big fan of Alcott, so I'd love to attend that dinner with all these wonderful writers and bring her along!

reading_frenzy at yahoo dot com

Wonderful interview! Thank you.

I too love the idea of what would you serve to these 12 guests. :)

Make it a great day!

This book sounds very interesting and I'd love to win a copy of it.

This book sounds great. Thanks for the chance to win a copy.

This sounds like an amazing book! I can't wait to read it.

Supeer interview--questions and answers.

Nava's experience shows how adaptable writers must be to succeed.

Sounds like a yummy book!

Donna v.

http://donnasbookpub.blogspot.com

Intriguing interview. I am eager to read your book. I think reading about the triumphs and challenges of great authors gives us writers insight into our own thought processes and offers courage along the erratic road to publication.

This book sounds amazing! So many things I enjoy rolled into one book. Would be a great surprise gift for hubby to give me :)

Enjoyed reading about your eclectic writing life. I could relate to that because some people call me "creative". When what I really am is adaptable.

Most of my ideas come from others through watching & listening. I love taking an idea & seeing where it will go.

Like growing a plant, the satisfaction comes when it blossoms.

I'm eager to hear your thoughts on self-acceptance & more on the writing "keys" from the 12 literary ladies.

Wouldn't it be great for the Literary Ladies to have a lunch set by Judy Chicago.

Thanks for all your kind comments and interesting thoughts, everyone! I'm looking forward to hearing more.

A couple of people asked what I would serve the Literary Ladies. Not surprisingly, many authors, male and female, were foodies. Virginia Woolf said, "One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well."

I would serve the Literary Ladies the same kind of meal I serve any guests in my home: Seasonal, colorful, simple, and 100% vegan. The concept of being vegan was not present in most of their lifetimes (though Alcott's family briefly toyed with vegetarianism in their utopian community, Fruitlands) so I would have a great time explaining the reasons for it.

What a great fantasy!

I will readily admit that I need some pointers for writing. I'm constantly distracted by life - and the time in front of the computer writing is what suffers. So bring on the pros and let me learn from them!

I can't wait to read this book and add it to my writing library.(What a hoot it would be to win it)

My question is: Did you need permission from their estates to get access and use their private material?

A personal note: Years ago, I was honored to be a member of M. L'Engle's writing workshop and so pleased to see you included her as one of the 12 writers. She would have been "tickled pink."

Your interview of questions and answers is very important to us that struggle as newbies each day in creating. I would certainly benefit to have this book in my library. I'd love to win this book for sure. Thanks for offering it, and the opportunity to win. I hope I win!

Sharing His Love,

Barb Shelton

barbjan10 at tx dot rr dot com

What an amazing collection of inspirational text by an inspiration herself. I LOVE hearing about and from women writers who are also artists and who stretch beyond the bounds of what the world says is possible for creative people. Thank you for your great example, Nava!!

Jeanne

This looks like a great book! I love Madeleine L'Engle's writings on writing and would love to read the advice from all these other wise ladies. :)

Looks like an excellent book! I would love to win it!

This looks great! What a wonderful idea for a book! I'm sure each of the authoresses would approve. I'd be very interested to read it, especially if I won it. :D

Another round of thanks for the comments after my previous response!

Lora Mitchell, I did have to do a lot of permission seeking. Though all the Literary Ladies are deceased, some of their estates are alive and well (Edith Wharton, Madeleine L'Engle, Anais Nin, etc) while others' writings are in the public domain (Alcott, Stowe, Austen, etc.). That whole permission-seeking and acknowledging is quite tedious and I'm going to try to avoid having to do it in the future!

And how cool that you got to study with L'Engle. As Alisha pointed out she did some great writing on the writing life.

Sounds like an inspiring read. Thanks for writing and I look forward to reading it!

Sounds exquisite! Can't wait to read the book. What a great idea.

Looks like a neat book!

Ahh! This book sounds like it was meant for me! Love Edith Wharton and Charlotte Bronte and I love reading about writers issues with writing. Usually it makes me feel more normal ;)

It's got my attention. Sounds like an excellent book.

The quote by Joan Didion that goes, "I write entirely to find out what I'm thinking..." fits me like a spandex glove. I want, no, need to read the book. I am sure many of the things that drove the women of the book will also fit me. It will be an inspiring read.

Love books on the writing life. Thanks for the giveaway!

Next to writing and reading books, my favorite thing is to read about others who write. Would love to have a copy of this book!

Looks fab, can't wait to read this book for some much-needed inspiration!

Jennifer

I'd love to win the Literary Ladies book. Please toss my name into the hat!

Great interview, fascinating to hear about Atlas' three niches. Would love to win the book!

This sounds like it would be a great addition to my library shelves.

apoalillo At Hotmail (dot) cOM

I would love this book.

[email protected]

A perfect dose of inspiration to leave right out on the coffee table!

I think this book must have been written with me in mind. I can't wait to read it.

I enjoyed the interview. I can't wait to read this book!

Looks like a great book! I'd be interested in reading it, even if I don't win.

As a writer, I'm always looking for inspiration and ways to improve my writing skills, this sounds like a great book! I would love to have this as part of my own library and share with my other writer friends. Best wishes, Nava on your publicity tour and getting published.

I'd love to win this book

Such an interesting group of women you chose. I just know it will be a very interesting book to read.

great giveaway thanks

willdebbie97 at yahoo dot com

Both my daughter and my mother would love this- thanks for the chance to win. Great interview. :)

(email in profile)

I need this. I'm all tapped out on writing inspiration and advice.:)

ladyspy79(at)aol(dot)com

i would love to win

susansmoaks at gmail dot com

This sounds like a fascinating book. I fancy myself a writer and love to gain insight into how other writers think.