new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: create a character, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 14 of 14

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: create a character in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

COMING: March, 2015

Guest post by K.M. Weiland

Ooh, bad guys. Where would our stories be without their spine-tingling, indignation-rousing, hatred-flaring charm? It’s a legit question. Because, without antagonists to get in our heroes’ way and cause conflict, we quite literally have no story.

So write yourself a warty-nosed, slimy-handed dude with a creepy laugh. No problemo, right? Bad guys aren’t nearly as complicated as good guys. Or are they? I would argue they’re more complicated, if only because they’re harder for most of us to understand (or maybe just admit we understand).

The best villains in literature are those who are just as dimensional and unexpected as your protagonists. They’re not simple black-and-white caricatures trying to lure puppies to the dark side by promising cookies. They’re real people. They might be our neighbors. Gasp! They might even be us!

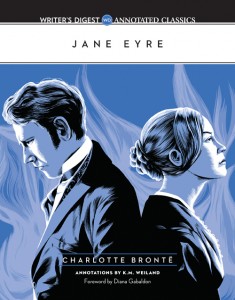

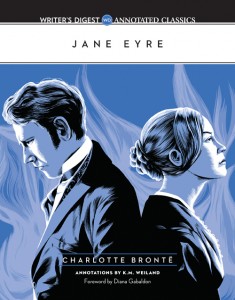

That raises some interesting possibilities, doesn’t it? It also helps us realize that villains can come in many different shapes and sizes. While studying Charlotte Brontë’s rightful classic Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic), I identified four major types of villain.

That raises some interesting possibilities, doesn’t it? It also helps us realize that villains can come in many different shapes and sizes. While studying Charlotte Brontë’s rightful classic Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic), I identified four major types of villain.

The Evil Villain: Mr. Brocklehurst

When we think of villains, this is the type we think of most often. He’s just nasty. He’s cruel, hypocritical, self-serving—and readers just want to punch him in the face. He may take the form of a mafia don, a dictator, a serial killer, or even something as comparatively “harmless” as an overbearing father.

In Jane Eyre, the evil villain manifests deliciously in the tyrannical Mr. Brocklehurst, the head of the horrible boarding school where Jane’s aunt disposes of her. Brocklehurst isn’t evil because he’s out killing, raping, or stealing. He’s evil because of his complete lack of compassion and his sadistic pleasure in his own power. When a young Jane dares to stand up to him, he subjects her to cruel punishment and lies about her to the rest of the school.

Even worse, he pretends he’s a pious benefactor. He has no idea he’s a cruel bum. He believes he and his school are saving these poor girls! Always remember that even the most evil villains will rarely recognize their own villainy. As far as they’re concerned, they’re the heroes of their own stories. Lucky for us, their hypocrisy only ups the ante and makes them more despicable.

The Insane Villain: Bertha Mason

Sometimes villains aren’t so much deliberately bad as psycho bad. They’re out of their heads, for whatever reason, and they may not even realize how horrifically their actions affect others. Psychos are always popular in horror stories for the simple fact that their near inhuman behavior makes them seem unstoppable. If they can’t understand the difference between right and wrong, what chance will your hero have of convincing them of the error of their ways—before it’s too late?

Perhaps the most notable antagonist in Jane Eyre is the one readers don’t even see for most of the book. She’s on stage for only a few scenes and mentioned outright in only a few others. But her presence powers the entire plot. [SPOILER] I am, of course, talking about Bertha, the mad wife of Jane’s employer and would-be husband Edward Rochester, whom he secretly keeps locked in the attic. [/SPOILER] The whole story might not even have happened had Bertha not been bonkers.

The insane villain is a force of nature. Although there will always be motivations for their behavior (even if they’re only chemical), they are people who aren’t behaving badly for sensible reasons. They can’t be rationalized with, and they won’t be moved by empathy for others. Their sheer otherness, coupled with their immovability, makes them one of the most fearsome and powerful types of villain.

The Envious Villain: Blanche Ingram

The envious villain is your garden-variety bad guy (or girl). These folks are a dime a dozen because their motivations and desires are ones almost all of us experience from time to time. Their envy, ego, and personal insecurity drives them to treat others badly for no other reason than spite (whether it’s petty or desperate).

Halfway through her story, Jane Eyre faces a formidable rival for Mr. Rochester’s love—the beautiful Blanche Ingram. Blanche is everything Jane isn’t (she’s the popular girl to Jane’s lunch-table outcast): gorgeous, rich, accomplished, and socially acceptable. On the surface, Blanche has no reason to fear or envy our plain-Jane protagonist. And yet, right from the start, she senses Jane as a threat to her marriage plans, and it immediately shows in her snide, condescending, and sometimes downright cruel behavior.

Envious villains are often those who, like Blanche, seem to have it all. But their glamour disguises deep personal insecurities. No one is ever a jerk for no reason. There’s always something (whether it’s a spoiled childhood or low self-esteem) that drives these most human of all villains. But don’t underestimate the power of their antagonism. Their envy can cause them to commit all sorts of crimes—everything from rudeness to murder.

The Ethical Villain: St. John Rivers

This is my personal favorite villain type—because he’s so darn scary. The ethical villain, like the envious villain, is less noticeable in his antagonism than are evil and insane baddies. This guy isn’t even a bad guy at all. He’s a very good guy. But he’s taken his goodness to the extreme. He’s on a crusade to save the rest of the world—either including or in spite of the protagonist—and heaven help anyone who gets in his way. He’s convinced the means absolutely justify his holy end.

Jane’s cousin St. John Rivers is a marvelous character. He is a man who is determined to live righteously and make his life count for some deeper purpose. He surrenders his own love for the village belle in order to go to India as a missionary. Doesn’t sound so bad, does it? And yet, his cold-hearted devotion to what he views as his duty, and his determination to make Jane adhere to those views, presents her with her single fiercest and most dangerous antagonist. St. John would never dream of harming Jane or committing a crime, but his fanaticism for his cause very nearly destroys her life.

The ethical villain is ethical. He conforms to most, if not all, of society’s moral norms. But somewhere along the line, those ethics fail to match up with the protagonist’s. That exact point is where he becomes an obstacle (and therefore an antagonist) to the hero. But he also offers us one of our richest opportunities for exploring moral gray areas and deep thematic questions. As such, he is arguably the most valuable villain type in your author’s toolbox.

The possibilities for antagonists are every bit as rich as they are for protagonists. Stop and take a second look at your story’s villain. Does he fit into one of the four categories we’ve discussed here? How can you take full advantage of that category’s opportunities for creating a compelling opponent? Or would your story benefit if you used a different kind of villain? Or maybe more than one kind side by side? The choices are endless!

–

K.M. Weiland

lives in make-believe worlds, talks to imaginary friends, and survives primarily on chocolate truffles and espresso. She is the IPPY and NIEA Award-winning and internationally published author of the Amazon bestsellers

Outlining Your Novel and

Structuring Your Novel. She writes historical and speculative fiction from her home in western Nebraska and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

Now available!

A story’s point-of-view is crucial to the success of a story or novel. But POV is one of the most complicated and difficult of creative writing skills to master. Part of the problem is that POV can refer to four different things, says David Jauss, professor at the University of Arkansas-Little Rock, in his book, On Writing Fiction: Rethinking Conventional Wisdom About Craft.

This is part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Here are links to parts 2 and 3.

Outside

Outside/Inside

Inside

Definitions of Point of View

- Your personal opinion. You might say, “From my point of view, that’s wrong.”

- The narrator’s person: 1st, 2nd, or 3rd.

- The narrative techniques: “omniscience, stream of consciousness and so forth”

- “. . .the locus of the perception (the character whose perspective is presented, whether or not that character is narrating)” (p. 25)

The first definition is a personal, not a literary one, so it doesn’t apply here. The second definition (the narrator’s person) is perhaps the most widely discussed, but Jauss says it isn’t helpful to a writer as s/he approaches a story. In fact, what often happens is these definitions collide and the generally accepted wisdom is that you must stay in only one POV, you can’t use some techniques in some POVS, and the narrator is a side-issue. These conventional rules, though, conflict with actual practice, says Jauss. Further, they prevent writers from controlling one of the most important aspects of fiction: how close the reader feels to the characters. (p. 26, 36)

I love the idea that point of view is a technique: it is one of the tools in our writer’s tool box that we can pull out as needed to accomplish something in a story. I love the idea that point of view allows you to pull the reader closer to the characters or to shove them away from the character. Right away, Jauss has me. And it only gets better from here. More complicated, but better.

Let’s discuss point-of-view, and use Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Let’s discuss point-of-view, and use Ivan, the One and Only, by Katherine Applegate, winner of the 2012 Newbery Award as the mentor text for the discussion.

Traditional Point of View

Jauss points out that traditionally point-of-view is discussed in terms of person, and defined by the pronouns used.

First person uses I, me, my, myself and so on; the story is told from inside the narrator’s head and the reader is privy to all the narrator’s thoughts and emotions.

Third person uses he, she, they and so on; the story is told as if there was a camera above the narrator’s head and the reader knows only what the narrator sees. A close third person allows the narrator’s thoughts and emotions to be conveyed to the reader.

Second person is seldom used and talks directly to the reader using you as the main pronoun.

POV techniques include the omniscient POV, which dips into different character’s heads to give the reader a look at the thoughts and emotions of multiple characters; the camera can change from one reader’s head to another, as the story demands.

Point of View as Technique for Getting into a Character’s Head

Point of view, according to Jauss, should be classified by how far into the character’s heads the reader is allowed to go. He proposes a continuum from fully Outside POV, to a POV that is both Outside and Inside and finally a POV that is fully Inside.

Outside, Outside & Inside and Inside. That’s the three new categories of POV. Jauss gives examples of these POV from what we would traditionally call first-person and third-person POV; I’ll be giving examples from the “first-person” book, Ivan, the One and Only. Ivan is undoubtably written in what most would call 1st person POV. The silverback gorilla, Ivan, is narrating the entire story. As such, it has a simple vocabulary and uses simple sentence structure to match the intelligence of an animal; but this animal has a big heart and that’s where technique allows the writer to manipulate how close the reader comes to the character.

OUTSIDE POV: What the Reader Infers about Character

Dramatic. Jauss says, “There is only one point of view that remains outside all of the characters, and that’s the dramatic point of view. . .”

Jauss defines this as a story in which the narrator is telling a story from outside all the characters AND uses language unique to the narrator. Notice that for Jauss, the narrator is an important part of distinguishing the POV technique used.

Dramatic storytelling is the the traditional show-don’t-tell kind of storytelling, where some insist that you must show everything and the reader should understand the action and emotions simply from what is shown.

In the “Bob” chapter of IVAN, we find an example of this, where a small dog interacts with the gorilla:

“He hops onto my chest and licks my chin, checking for leftovers.”

Even though the narrator is Ivan and he is including himself in the action, it is still dramatic action. Nothing in this statement gets inside of Ivan’s head; it’s purely dramatic. In fact, most of the “Bob” chapter is dramatic telling from Ivan’s point of view. He dips into his own feelings (indirect or direct interior dialogue—see discussion later) a few times, but it’s mostly dramatic.

One common demand for a dramatic POV is that the reader understand the character’s emotions only from the actions. If angry, a character might tighten his fists, or his brow might furrow, or he may bare his teeth. Jauss says “the story that results is inevitably subtle. Careless or inexperienced readers will often be confused by stories employing this point of view.” (p. 40)

What a breath of fresh air! Some writing teacher emphasize this Show-Don’t-Tell to the extreme and yet Jauss says the results are “inevitably subtle.” Because I write for kids, I must question whether “subtle” is what I want! I’ve long thought that the Show-Don’t-Tell is more a plea for stronger sensory details than for implied emotion, and have modified it to say, Show-Then-Tell-Sometimes. What I mean is that the sensory details should put the reader into the situation; but after you’ve done that, sometimes you must interpret the actions for the reader.

“Jill slapped Bob, leaving a red palm print on his cheek.”

That uses sensory details; it shows, and doesn’t just tell. But we don’t know WHY Jill slaps Bob. Did she do it to wake him up after he passed out?

“Desperate, Jill slapped Bob, leaving a red palm print on his cheek.”

That word, “desperate,” pulls the sentence out of a strictly dramatic telling and starts to drill down into Jill’s emotions. However, we need that word in order to understand the story.

This technique isn’t used extensively throughout IVAN, but here’s one example. The small elephant, Ruby, is watching the older elephant Stella do her tricks with Snickers the circus dog.

“Ruby clings to her like a shadow. Ruby’s eyes go wide when Snickers jumps on Stella’s back, then leaps onto her head.”

We aren’t TOLD that Ruby is scared of the dog; instead, “Ruby’s eyes go wide.” The reader must infer Ruby’s emotions from that bit of action. And here, it works well. We don’t need an extra adjective for interpretation. Applegate does an amazing job of walking this fine line and keeping the action strictly dramatic.

Dramatic storytelling is like watching a play on stage, or watching a movie. We can never go deeper into a character’s point of view, because the camera can’t go inside a character. The closest we can come is the constant monologues that are a technique of reality TV, where a character talks to the camera and interprets a sequence of actions or explains their thoughts during a sequence. Even that doesn’t take you inside the character like the next techniques can. For the Outside/Inside techniques, join us tomorrow.

This has been part 1 of a 3-part series on Point of View: Techniques for Getting Inside a Character’s Head. Tomorrow, will be Outside/Inside: Partially Inside a Character’s Head

START YOUR NOVEL

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter

- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

The Math adds up to one thing: a publishable manuscript.

Download a sample chapter on your Kindle.

On my current WIP novel, I am revising to make sure the character relationships are consistent. The main character has three main relationships in the story, with a friend and traveling companion, with her father and with the villain.

Among other things, a first reader pointed out some inconsistencies in these relationships. I agreed and decided to tackle this. The first thing I did was the re-read the manuscript and find the places where the main character interacts with each of the others.

It was actually fairly easy because each interaction had about three chapters each, at least in the first half of the novel that I am working on. I physically separated these into three stacks of paper and then marked them up. I was looking for emotional content, reactions to each other, all those small things that create a relationship. Surprisingly, these can be a small part of chapter/scene. You’ve got to have the action going along and the plot will take up a lot of space. There’s description and dialogue. Some of the emotional stuff is in all of this because you can and should color any of it with an attitude.

But surprisingly little of it directly reflects the relationship between these two characters.

Now, I just need to decide on what the relationship should be–actually the hardest part of all. For a father-daughter relationship, should the father be wishing for a son, instead of a daughter? Or does he support his daughter in all her hopes and dreams? Of course, we know what the perfect father would do. But this is fiction, which about dysfunctional families, and the ways in which relationships can get tangled up. Once I decide where it should go, then it will be easy to see where to revise.

Then, I just need to repeat it for the other two relationships.

For me, it is easier to gain consistency by pulling out chapters like this to look at a specific aspect of the story.

START YOUR NOVEL

Six Winning Steps Toward a Compelling Opening Line, Scene and Chapter

- 29 Plot Templates

- 2 Essential Writing Skills

- 100 Examples of Opening Lines

- 7 Weak Openings to Avoid

- 4 Strong Openings to Use

- 3 Assignments to Get Unstuck

- 7 Problems to Resolve

The Math adds up to one thing: a publishable manuscript.

Download a sample chapter on your Kindle.

Dialogue, what characters say, is an important element in any story.

DH, a reader here, is puzzled how to switch from one character to another.

Here’s an example she gave:

“Hey Danielle! Come check out this new book I got!” says Viola. “Okay just a sec.” says Danielle.

See, what I’m asking? I need to know what ways are there to talk between characters without having to say says Danielle, or says Viola or says Darcy.

Dialogue is what characters actually say and it is set off with quotes. Each time a character finishes talking and another begins, it is a new paragraph. If the character’s speech is a sentence, then it ends with a comma that goes inside the quote. If it is a question or exclamation point, that goes inside the quote instead of the comma. Generally, stories are told in past tense, so you would use “said” instead of “says,” which would be used for first person stories. And finally, I tend to put the character’s name before the said/says. In some ways this is a personal preference, but some references consider “said Viola” to be more juvenile than “Viola said.” Decide which you like and stick with it. It’s also a pet peeve for a character to constantly call the other person’s name. I don’t talk to people that way and characters shouldn’t either.

“Hey, come check out this new book I got!” Viola said.

“Okay, just a sec,” Danielle said.

That’s a good basic dialogue structure but now there are things that can help the story move along smoothly. First, is a beat or some sort of action. You can also insert the “she said” into the middle of the dialogue to vary the rhythm of the exchange.

Viola held up a shiny book. “Hey, come check this out!”

“Okay,” Danielle said. “Just a sec.”

Let’s add some setting.

From across the library, Viola held up a shiny book. “Hey!” she called in a stage whisper. “Come check this out!”

“Okay.” Danielle shoved back her chair and said, “Just a sec.”

It is also important to distinguish each character simply by the way they say something.

Viola: Hey, come check this out!

What are some possible responses for Danielle?

“Sure thing.”

“Why? Boring.”

“Girl, you know I don’t like books.”

“I’m busy.”

“Not now.”

“Go away.”

(Silence. She ignores Viola)

“Be quiet.”

Which one would THIS Danielle be most likely to say? It’s a matter of character. What is her attitude about reading and books and being in a library? What is her emotional state? Is she mad, sad, bored, or engrossed in a book of her own? All of those things will infuse the dialogue with something unique. And the reader should be able to tell Danielle’s voice from Viola’s. Because you also know all that about Viola and that should be in what she says and how she says it.

From across the library, Viola waved the new Harry Potter book. “It’s here! Come check it out.”

“Okay.” Danielle yawned, then put down her worn copy of Pride and Prejudice. “I’m coming.”

Dialogue must do more than just have people talking. It must also characterize and show attitude and move the story along. It’s worth the time it takes to explore options.

Adding emotional depth to a novel is important enough to warrant a special pass through the manuscript. This video talks about how I did that on a recent mss.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

This is an experiment with doing a video to explain something about writing and revising. Please comment and let me know what you think about doing this with video.

I just named some characters, Jane and John Smith. What does that say about these characters? Do you think boring? No, no, think alias. Think clueless that such an alias might be too transparently an alias. What would make them so clueless? Ah, you’re getting interested in my characters just from their names? One hopes so!

What connotations do your characters’ names have? Abraham, might be Biblical or it might be Presidential. Either way, it evokes a certain set of expectations about your character that you can play against or reinforce, as needed.

In some ways, it’s just the normal exactness that you need with any of your language. But this is a very important tag for your character. When you name your character, think about these things:

Top 5 Tips on Naming Your Characters

Meaning of the name. Buy a good baby name book or something like The Writer’s Digest Character Naming Sourcebook. What does the name mean and how does that relate to the character qualities you want to show-don’t-tell? You can use it to reinforce or contrast. For example, my name means Dark Fortress, while my husband’s name means Blond Warrior. Kinda nice combination, don’t you think, a love story meant to endure!

Meaning of the name. Buy a good baby name book or something like The Writer’s Digest Character Naming Sourcebook. What does the name mean and how does that relate to the character qualities you want to show-don’t-tell? You can use it to reinforce or contrast. For example, my name means Dark Fortress, while my husband’s name means Blond Warrior. Kinda nice combination, don’t you think, a love story meant to endure!

- Origin of name. Does the name come from a certain language, time period, or ethnic group? How does the origin affect the connotations for the name?

- Think of possible nicknames for this name. What complexities can you bring to the character just by using an apt nickname? Will the nickname contrast or reinforce the real name? For example, Rebecca could be called Bec, or she could be called something totally unrelated like Wisdom.

- Say the name out loud. Is it easy or hard to pronounce? Does it “trip off the tongue lightly”? Or, does it tie the tongue in knots? What would each of these options say about your character? Will the reader be put off by a hard-to-pronounce name? Or is it an expected part of your genre, like fantasy or science-fiction?

- Try out several names. Write a sample chapter using the name, but use the Find and Replace on your word processor to change out the name for an alternate. Reread the chapter. Which name seems apt? Repeat until one feels right on all levels!

| |

NEW EBOOK

Available on

|

For more info, see

Character’s Job Affects Your Novel

When you think about a character’s profession or job, what are you looking for?

Stand out. Usually, you want something that will stand out. Maybe taxidermist, taxi driver, armored car driver. The ch

Stand out. Usually, you want something that will stand out. Maybe taxidermist, taxi driver, armored car driver. The ch

Implications of the Job. Think carefully about the implications of the job. This might be considering the tools they use, the hours they work, the type of people they will work with and will serve. All these things are grist for the mill of your story. You’ll have to SHOW-Don’t-Tell the character at work, so you’ll need all these details. How will it work into the story? For example, a butcher deals with knives and housewives; are either of those important in your story?

Roles and Hobbies. Even children/students need an interesting job or role in life. This can come from their passion for studies, their family situation, or their hobbies. Maybe your character is just ten years old, but is already on the way to being a champion at tying fishing flies. Or, maybe they like photographing birds and can identify anything that flies by at a glance.

Plot. Think about when and where your stories events could happen because of this particular job. The list will be short: will those places/events work for your story?

Theme. Finally, think about the theme of your story, what is the underlying moral pinnings of your story? Are you telling a story of healing? Then look for medical jobs. Are you telling a story of revenge? Jobs that require some heavy physical activity would lead to a story of violence.

Of course, in all these things, you can go for the total opposite: a story of healing takes place in a jail (Character’s job: inmate). A story of violence happens in a nunnery.

Think carefully about the jobs/roles you assign to each character because it has implications for the whole story.

Give Readers a Larger Than Life Protagonist

In my new novel, I’ve written about a dozen different openings, looking for a voice that works. I’m settling in on one, but the first chapter is still unsteady.

One thing I’m looking at today is how to make the main character, the protagonist, larger-than-life. In Writing the Breakout Novel Workbook, Donald Maass emphasizes the need for characters who rise above the ordinary and do it right away, in chapter one.

Maass suggests, for example, that you think of things your protagonist would never ever say, think or do; then find a situation in which they MUST say, think or do that very thing.

Maass says, “What qualifies as larger-than-life action? Winking at a stranger is easy for a flirt; to a shy person it is huge. Taking a swing at someone is no big deal for a boxer; for me, it would be life changing. Whatever it is, it is a surprise. It feels big. It feels outrageous.” (p.31)

Use Placeholders for Zingers

Also, use placeholders for dialogue, description, etc. Mark these clearly as placeholders, so you remember to come back and put in some type of Zinger! Make that bit of your novel memorable in some way.

I like this idea a lot because I don’t think fast on my feet. I’d be terrible at public debates. I can however, with time, think of a great retort. That’s what this is. Thinking of that great way of saying something and adding it later. It’s nice to know that I can write the basics of a novel and go back later to add in the good stuff.

Turn Up the Volume

Another way to say this is to turn up the volume. Or turn it down. In other words, use a range of characterization that provides quiet spots and gloriously large spots. A wide dynamic range. Don’t forget about the quiet spots, they are needed for contrast.

Random Acts of Publicity Week September 7-10

Have you joined The Random Acts of Publicity Week event page on Facebook?

Answering the WHY? question

It’s the WHY question that is plaguing me right now.

Why does my character want to participate in this project?

Why does she want this so much that she will jump out of her comfort zone in order to make it work? Why, why, why?

Oh, how I hate that question! It’s obvious to me that the character wants this because, well, because that’s the story I’m writing. Of course, she wants to do this. Boy, am I in trouble.

I have to go back to the basics – again.

Interview the character. Find the back story details that answers the WHY? I’m such a private person that I hate telling people the whys of anything I do, so why should I expect my characters to be more forthcoming?

But how do you describe a fascination with something? For example: There’s no logical reason for me to like quilting, yet I do. I can make up something that will satisfy you, something about the puzzle of cutting up fabric and sewing it back together; but in the end, quilting transcends those explanations and I just wind up weakly saying, I love to play with color. Really, that’s it. I love to play with color and love the feel of the fabrics and love the semi-precision of sewing, fitting things together into a larger pattern.

How can I describe for a character a fascination with the tasks needed in this new story? There are multiple motivations: the inherent fascination with a hands-on process; the feeling of connection with a missing loved one; the reluctant joy of being pushed out of comfort zones to meet more people and to open up more; the surprise of watching how the project affects others. It’s so many small things that motivate my character. How to put those into the story?

Maybe part of the answer is that I was looking for a single answer, a single incident that motivates her and in reality, it must be multiple small things, which are woven into multiple scenes.

I’m wrestling today with that awful WHY? What are you wrestling with?

Related posts:

- Measuring Progress

- How Do You Get Back Into A Story?

Make supporting characters interesting

Wednesday, I went to north central Arkansas to teach a professional development class and on the way up, I listened to an audio version of T is for Trespass by Sue Grafton, the 20th Kinsey Millhone mystery.

At one point the detective calls a college to do a background check on a suspect. The supporting character here was the clerk at the college, and writing the scene was made more difficult because it was just a phone conversation. How do you characterize a minor supporting character when you only present them in one phone conversation?

Husky voice. Nasal voice. In short, the character’s voice. That’s about it, right?

Instead, Grafton gives the character a cold, and now, she is sneezing, blowing her nose, and she’s grumpy, all of which adds an extra layer of interest and conflict to an otherwise straightforward request for information.

Instead, Grafton gives the character a cold, and now, she is sneezing, blowing her nose, and she’s grumpy, all of which adds an extra layer of interest and conflict to an otherwise straightforward request for information.

The grouchy clerk tells Millhone it will take five business days to get the information, that is, five days after Millhone shows up with the signed employment application giving permission to release the information. Millhone is aggravated, but dutifully trots down to the college to show the application, only to find that clerk has gone home early because she felt so bad. Of course, that’s great for our heroine, because she innocently tells the new clerk that the information was supposed to be waiting for her. The new clerk retrieves the information in less than ten minutes.

The college clerk is a minor supporting character, but the quick characterization of a grumpy woman with a cold kept the story moving with a minor, but appropriate conflict that provided a nice plot twist when the information was retrieved fast, instead of slow.

Do you have minor characters who are cardboard cut-outs? Here are 4 quick ways to characterize better. For an extra challenge, while you’re sharpening your minor characters, look for a minor plot twist, too!

- Ailments. Give them a cold. Or a broken arm. Or some other physical ailment that affects their speech, method of moving around, etc.

- Role. Give the character an unusual family role, such as great uncle, the black sheep of the family, the third wife, or the last of fourteen children.

- Job. Unusual jobs abound in the world: fireworks expert, laser welder, test kitchen for ways to cook rice, strawberry farmer, tarantula scientist, a person who cares for plants in skyscraper offices, or an Amish wife.

- Facial features. The human eye can perceive slight differences in faces, so that each of the billions of people on earth looks unique. Work to find ways to describe faces in unique ways. Use metaphors, find the one details that stands out, or exaggerate a feature.

Related posts:

- Options for Picture Book Characters

- Novel Characters Transform

- Snooping on Characters

Charlotte was Blood-Thirsty: Character Paradoxes

Charlotte, from E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, is remembered as a character of great warmth for her friendship with the unlikely pig, Wilbur. Poor Wilbur, once the runt of the litter and saved only by the whim of a girl, is fattened up and ready for slaughter. (This is a story set on a working farm and, as such, it’s not a story of cruelty, but of practicality.) Only the spelling abilities of Charlotte save him.

Crab spider eating fly

Charlotte makes friends with Wilbur and even travels with him to the fairgrounds, so she can weave webs above his stall there. She has great wisdom, great commitment to her friend, and she’s blood thirsty. Well, she’s a spider, she has to be blood-thirsty, doesn’t she? Otherwise, she won’t eat. But in the context of friendship, it’s a sobering fact, a repugnant habit.

What paradoxes have you built into your characters to make them interesting?

- Beautiful until she opens her mouth and croaks.

- Obedient, yet with a love of taking risks.

- Explorer with a formal dress at the bottom of her backpack.

- Athletic, but has a weakness for doughnuts.

- Self-reliant, yet lonely.

- Dangerous, yet gentle.

To find appropriate paradoxes, you can work against the setting or with the setting. Of course, Charlotte would be “blood-thirsty” because spiders inject victims with venom that liquefies their insides; okay, technically then, not blood-thirsty but just on a liquid diet. But it works.

Do research about your character’s job, role, location, etc. Take for example, a football player from Kansas.

The cliched image of football players are rough, tough, not-so-smart (except the quarterback) big-muscled guys. A paradox would be a love of opera or ballet.

A Kansan lives in the prairies and is used to howling winter winds, farm life, livestock and tornadoes. A paradox would be someone with agoraphobia, or fear of open spaces.

What paradoxes can you add to your characters to enliven them?

Related posts:

- American Fantasy: The Underneath

I’ve been reading a great new psychology book that should help in developing characters, especially the settings which reveal so much about a character.

Snoop

Snoop: What Your Stuff Says About You by Sam Gosling, Ph.D. is a fascinating book by a psychologist who studies a person’s environment and what that environment says about you.

Snoop: What Your Stuff Says About You by Sam Gosling, Ph.D. is a fascinating book by a psychologist who studies a person’s environment and what that environment says about you.

For example, in a bedroom:

Variety of books, magazines, music — this is a person who is open to new experiences.

Well-lit, uncluttered and organized books and music — this is a conscientious person.

Inspirational posters — this is a negative or anxious person.

In an office:

Distinctive decor, stylish, unconventional, varied books — this is an open person

Good condition, clean, organized, neat, uncluttered — this is a conscientious person

Decorated, cheerful, inviting — this is an extravert

High-traffic location — this is an agreeable person

Decorated — this is a negative or anxious person.

Not only does he tell you what to look for, he also details the things that people mistakenly look at when trying to evaluate a person’s psychology.

Examples of things people tend to rely on, but shouldn’t, in a bedroom:

Stale air does not indicate a negative or anxious person

Cheerful and colorful does not indicate an agreeable or a conscientious person

Decorated and cluttered does not indicate an open or extraverted person

In an office:

An uninviting office does not indicate a negative or anxious person

A comfortable office does not indicate a conscientious person

An inviting office does not indicate an agreeable person

The nuances of our Stuff are fascinating to read about and the book is easy to read. It’s a good resource when you are creating new characters.

That raises some interesting possibilities, doesn’t it? It also helps us realize that villains can come in many different shapes and sizes. While studying Charlotte Brontë’s rightful classic Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic), I identified four major types of villain.

That raises some interesting possibilities, doesn’t it? It also helps us realize that villains can come in many different shapes and sizes. While studying Charlotte Brontë’s rightful classic Jane Eyre (which I analyze in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classic), I identified four major types of villain.

Snoop: What Your Stuff Says About You

Snoop: What Your Stuff Says About You