Weaver, Janice. 2010. Hudson. Illustrated by David Craig. Ontario, Canada: Tundra. (Early Reviewer Copy from LibraryThing)The Hudson River, the Hudson Bay, the Hudson Strait - all bear the name of Henry Hudson, the English explorer. Though he never found the northern passage to China that he was seeking, Janice Weaver’s new book, Hudson, shows that he was likely a competent and fearless seafarer, and ultimately helped to advance humankind’s knowledge of the world. Working with the very minimal details available about Henry Hudson’s life, Weaver creates a compelling, understandable portrait of Hudson’s complex life, using period quotes whenever possible, "I hoped to have a clear sea between the land and the ice,” wrote Hudson in his journal, “and be able to circle north of this land.” The book is divided into short, chronological, illustrated chapters that recount his early life, his four major voyages (1607-1610), the mutiny that likely claimed his life, and its aftermath. Text insets offer additional information to add interest and context to the story. “The Art of Navigation” inset contains a photograph of a seventeenth-century astrolabe and a short explanation of its use and of the many difficulties of sailing in an age when sailors had to rely on the stars to determine their location. Other insets highlight the whaling and spice trades. Particularly interesting is “Of Mariners and Mermaids,” in which readers are reminded of the superstitions of the time. In Hudson’s journal entry for June 15, 1608, he records matter-of-factly that his men have spotted a mermaid swimming alongside the ship. “She was close to the ship’s side,” he reports, “and looked earnestly at the men.... As they saw her, from the navel upward, her back and breast were like a woman’s... and she had long black hair hanging down behind. In her going down they saw her tail, which was like the tail of a porpoise, and speckled like a mackerel.” David Craig ( Amelia Earhart: Legend of the Lost Aviator) contributes original paintings depicting life as a seventeenth century mariner. Full-page illustrations of sailors chopping ice, facing stormy seas, and braving icy decks highlight the extremely dangerous nature of early seagoing exploration, particularly when traveling North of the Arctic Circle in a small wooden boat. In addition to the original artwork, images of period maps, paintings and other realia add more interest to an already fascinating story. Further reading sites, historic sites, credits and an index follow this fascinating look at a fascinating explorer. Interesting and well researched. Recommended for ages 9 and up. Note: Don’t seal down the dust cover on this one. The inside of the jacket is an attractive poster with map!It’s Nonfiction Monday! Today’s host is thebooknosher. Stop by! Share

This action-packed, real-life story of Marie Peary, the daughter of Arctic explorer Robert E. Peary, is a wonderful introduction for tweens to the family life of a great explorer. Most often, the families of famous explorers were left at home in relative safety while the explorers (usually men) were gone for months and years at a time traveling to unknown and often dangerous parts of the world. This action-packed, real-life story of Marie Peary, the daughter of Arctic explorer Robert E. Peary, is a wonderful introduction for tweens to the family life of a great explorer. Most often, the families of famous explorers were left at home in relative safety while the explorers (usually men) were gone for months and years at a time traveling to unknown and often dangerous parts of the world.

However, the Peary family was quite different. The real star of this unusual story is Peary's wife and Marie's mother, Josephine. Breaking with the convention of the day, Josephine traveled with her husband on several of his attempts to find and claim the North Pole. In fact, Marie was born in a remote northern corner of Greenland during one of these expeditions.

Marie's earliest memories and friendships were with some of the Inuit people who populated the far north. Her family depended on these kind people for help as guides and in constructing clothing to protect them against the fierce cold. Marie spent months and years living aboard ship going to and from Greenland. In fact, she and her mother, along with the ship's crew, were locked into the ice for 10 months in 1901 while trying to reach her father's new base camp.

Marie and her family developed close relationships with some of the Inuit and considered them friends. For a good part of her early life, Marie lived and played among Inuit children and had many adventures with them. Sledding down an ice mass and finding fun on nearby icebergs with her Inuit friends was a frequent pleasure.

The Inuits gave Marie the name "The Snow Baby" when she was born with blond hair and blue eyes. The book makes clear that there was much mutual respect and affection between the various explorer parties and the Inuits, and that there personal association extended over a period of years during Peary's many expeditions to the Arctic. In fact, it took until Marie was 16 before her father successfully journeyed to the North Pole and claimed it for the United States.

The book's author, Katherine Kirkpatrick, has made good use of her source material. This remarkable story is significantly enhanced with a generous collection of photographs. Even though some are extremely grainy, most are clear images of their lives in northern Greenland. The bulk of the book concerns itself with Marie's early years as part of the expeditions. Even though she and her mother spent years moving back and forth between this adventure life and a conventional life in the states, Marie was separated from her father for long stretches of time while he remained in the Arctic to winter and prepare for the next foray to the North Pole. He and his expedition did not successfully reach and claim the North Pole until 2009. Those years in between were consumed with supplying and resupplying the expedition between forays.

For anyone interested in a non-conventional life, or intrigued by the spirit of adventure necessary to pushing out to the ends of the world, this is a delightful story. For one thing, it centers on a girl's experience and that is unusual in itself. Secondly, Marie had extraordinary, enlightened parents who saw nothing wrong with exposing their daughter to such an exceptional life. Marie grew up to spend many years of her adult life helping her father organize his notes and papers for the early National Geographic Society.

And in 1932, traveling to Greenland with her own two sons, Marie placed a monument honoring her father at the place where she was born - "the first piece of land sighted when a ship approaches Greenland from America."

By: Stacy Dillon,

on 11/29/2007

Blog: Welcome to my Tweendom

( Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

drunk driving, contemporary fiction, stepfamilies, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Tween, Friendship, Tween, drunk driving, contemporary fiction, stepfamilies, Atheneum Books for Young Readers, Add a tag

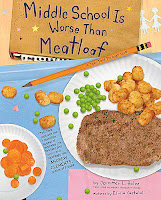

Ginny is just going into 7th grade, and she has a plan. From getting a new dad to looking good in her school photo, her list runs the gambit. Through a series of lists, letters, IMs, report cards, post-its, detention slips, brother-drawn comics, and overdue slips, readers get a real sense of what's going on in Ginny's life. While the format is super-cute, Jennifer Holm (yes of Babymouse and others) tackles some meaty issues. Ginny's dad was killed by a drunk-driver, and now her older somewhat delinquent brother seems to be on the same path as the teen who killed their father. Ginny is also dealing with more typical middle school issues. Mary Catherine Kelly still has Ginny's sweater, and she stillhasn't spoken to Ginny since she got the prime part at their ballet school. Ginny is also on a quest to make her nose seems smaller, and is wondering what to do about the fact that Brian Bukvic keeps bugging her. Ginny's got a great relationship with her mom and her Fairy Grandfather, which is evident through artifacts like long-distance phone bills (Grandpa is in Florida), and the notes that her mother leaves for her. Even though readers get a sense of family distance from the sheer volume of notes to each other, the author has managed to develop the character of the family itself so that the reader really can feel the love they all have for each other. I am going to be recommending this to reluctant readers, and also to the students looking for a super fast, yet thoughtful read.

|

Love the aquanaut photo.

Only 5% of the ocean- how amazing. What a future there is in that!

This sounds like a wonderful non fiction addition for our class library. Thank you!

I love books about chasing dreams and I enjoy looking at the ocean. Will be sure to check this one out. Thank you for the review!

I am hoping that it will be my daughter's future. She, too, has "lost her heart to the water." :)