new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: elements, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: elements in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: JulieF,

on 3/15/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

periodic table of elements,

#ACSSanDiego,

A World from Dust,

Ben McFarland,

chemical rules,

CHON,

How the Periodic Table Shaped Life,

magnesium,

sulfur,

Books,

chemistry,

evolution,

Multimedia,

periodic table,

elements,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Images & Slideshows,

Science & Medicine,

phosphorus,

Earth & Life Sciences,

chemical elements,

Add a tag

When people think of evolution, many reflect on the concept as an operation filled with endless random possibilities–a process that arrives at advantageous traits by chance. But is the course of evolution actually random? In A World from Dust: How the Periodic Table Shaped Life, Ben McFarland argues that an understanding of chemistry can both explain and predict the course of evolution.

The post How does chemistry shape evolution? appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

nicole,

on 9/25/2015

Blog:

the enchanted easel

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

the enchanted easel,

fine art america,

serafina,

fire goddess,

fantasy,

painting,

acrylic,

kawaii,

fire,

canvas,

whimsical,

flames,

tote bags,

elements,

Add a tag

for they did it again! have yet to find a better vendor for tote bags than these guys. these bags are GORGEOUS!!! color, spot on. the image fills up the whole entire bag, which is available in THREE different sizes. perfect for anything and everything.

big believer in giving credit where credit is due...and this one is well deserved.

thanks, f

ine art america for putting out yet another fabulous product! one happy little artist here!

{ps and btw, sun glare not included. ;) }

By:

nicole,

on 9/22/2015

Blog:

the enchanted easel

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fantasy,

red,

painting,

acrylic,

goddess,

etsy,

kawaii,

fire,

canvas,

whimsical,

traditional,

flames,

brunette,

elements,

the enchanted easel,

fine art america,

lotus flowers,

nuvango,

Add a tag

|

serafina~fire goddess

11x14 acrylic on canvas

©the enchanted easel 2015 |

i thought it might be fun to take on the four elements (in between commissions), so i began with a self-portrait of sorts...the true definition of a fire sign.

meet serafina, the goddess of fire. PRINTS (AND SUCH) can be found through the shop links

here. also, the ORIGINAL PAINTING is FOR SALE.

contact me if interested and please place the word SERAFINA in the subject line so i don't mistake it for spam/junk mail.

i'm hoping to get to the remaining elements (air, water and earth) SOON! :) currently working on a couple commissions....

Read the rest of this post

By: JulieF,

on 3/20/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

periodic law,

periodic system,

Books,

History,

chemistry,

Multimedia,

elements,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

history of science,

Science & Medicine,

Mendeleev,

Quizzes & Polls,

Early Responses to the Periodic System,

Gábor Palló,

Helge Kragh,

Masanori Kaji,

Mendeleev's periodic law,

Add a tag

The periodic system, which Dmittri Ivanovich Mendeleev presented to the science community in the fall of 1870, is a well-established tool frequently used in both pedagogical and research settings today. However, early reception of Mendeleev’s periodic system, particularly from 1870 through 1930, was mixed.

The post Early responses to Mendeleev’s periodic law [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julie Fergus,

on 8/20/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

This Day in History,

periodic table,

elements,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

history of science,

Science & Medicine,

Dmitri Mendeleev,

A Tale of Seven Elements,

chemical elements,

Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois,

John Reina Newlands,

Julius Lothar Meyer,

Add a tag

The discovery of the periodic system of the elements and the associated periodic table is generally attributed to the great Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. Many authors have indulged in the game of debating just how much credit should be attributed to Mendeleev and how much to the other discoverers of this unifying theme of modern chemistry.

In fact the discovery of the periodic table represents one of a multitude of multiple discoveries which most accounts of science try to explain away. Multiple discovery is actually the rule rather than the exception and it is one of the many hints that point to the interconnected, almost organic nature of how science really develops. Many, including myself, have explored this theme by considering examples from the history of atomic physics and chemistry.

But today I am writing about a subaltern who discovered the periodic table well before Mendeleev and whose most significant contribution was published on 20 August 1864, or precisely 150 years ago. John Reina Newlands was an English chemist who never held a university position and yet went further than any of his contemporary professional chemists in discovering the all-important repeating pattern among the elements which he described in a number of articles.

Newlands came from Southwark, a suburb of London. After studying at the Royal College of chemistry he became the chief chemist at Royal Agricultural Society of Great Britain. In 1860 when the leading European chemists were attending the Karlsruhe conference to discuss such concepts as atoms, molecules and atomic weights, Newlands was busy volunteering to fight in the Italian revolutionary war under Garibaldi. This is explained by the fact that his mother was Italian descent, which also explains his having the middle name Reina. In any case he survived the fighting and set about thinking about the elements on his return to London to become a sugar chemist.

In 1863 Newlands published a list of elements which he arranged into 11 groups. The elements within each of his groups had analogous properties and displayed weights that differed by eight units or some factor of eight. But no table yet!

Nevertheless he even predicted the existence of a new element, which he believed should have an atomic weight of 163 and should fall between iridium and rhodium. Unfortunately for Newlands neither this element, or a few more he predicted, ever materialized but it does show that the prediction of elements from a system of elements is not something that only Mendeleev invented.

In the first of three articles of 1864 Newlands published his first periodic table, five years before Mendeleev incidentally. This arrangement benefited from the revised atomic weights that had been announced at the Karlsruhe conference he had missed and showed that many elements had weights differing by 16 units. But it only contained 12 elements ranging between lithium as the lightest and chlorine as the heaviest.

Then another article, on 20 August 1864, with a slightly expanded range of elements in which he dropped the use of atomic weights for the elements and replaced them with an ordinal number for each one. Historians and philosophers have amused themselves over the years by debating whether this represents an anticipation of the modern concept of atomic number, but that’s another story.

More importantly Newlands now suggested that he had a system, a repeating and periodic pattern of elements, or a periodic law. Another innovation was Newlands’ willingness to reverse pairs of elements if their atomic weights demanded this change as in the case of tellurium and iodine. Even though tellurium has a higher atomic weight than iodine it must be placed before iodine so that each element falls into the appropriate column according to chemical similarities.

The following year, Newlands had the opportunity to present his findings in a lecture to the London Chemical Society but the result was public ridicule. One member of the audience mockingly asked Newlands whether he had considered arranging the elements alphabetically since this might have produced an even better chemical grouping of the elements. The society declined to publish Newlands’ article although he was able to publish it in another journal.

In 1869 and 1870 two more prominent chemists who held university positions published more elaborate periodic systems. They were the German Julius Lothar Meyer and the Russian Dmitri Mendeleev. They essentially rediscovered what Newlands found and made some improvements. Mendeleev in particular made a point of denying Newlands’ priority claiming that Newlands had not regarded his discovery as representing a scientific law. These two chemists were awarded the lion’s share of the credit and Newlands was reduced to arguing for his priority for several years afterwards. In the end he did gain some recognition when the Davy award, or the equivalent of the Nobel Prize for chemistry at the time, and which had already been jointly awarded to Lothar Meyer and Mendeleev, was finally accorded to Newlands in 1887, twenty three years after his article of August 1864.

But there is a final word to be said on this subject. In 1862, two years before Newlands, a French geologist, Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois had already published a periodic system that he arranged in a three-dimensional fashion on the surface of a metal cylinder. He called this the “telluric screw,” from tellos — Greek for the Earth since he was a geologist and since he was classifying the elements of the earth.

Image: Chemistry by macaroni1945. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The 150th anniversary of Newlands’ discovery of the periodic system appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 9/8/2013

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

periodic table,

copenhagen,

elements,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

eric scerri,

periodic,

scerri,

A Tale of Seven Elements,

atomic number,

chemical elements,

hafnium,

Henry Moseley,

Ida Noddack,

Lise Meitner,

Marguerite Perey,

X-ray radiation,

urbain,

moseley’s,

celtium,

moseley,

Add a tag

By Eric Scerri

After years of lagging behind physics and biology in the popularity stakes, the science of chemistry is staging a big come back, at least in one particular area. Information about the elements and the periodic table has mushroomed in popular culture. Children, movie stars, and countless others upload videos to YouTube of reciting and singing their way through lists of all the elements. Artists and advertisers have latched onto the iconic beauty of the periodic table with its elegant one hundred and eighteen rectangles containing one or two letters to denote each of the elements. T-shirts are constantly devised to spell out some snappy message using just the symbols for elements. If some words cannot quite be spelled out in this way designers just go ahead and invent new element symbols.

Moreover, the academic study of the periodic table has been undergoing a resurgence. In 2012 an International Conference, only the third one on this subject, was held in the historic city of Cuzco in Peru. Recent years have seen many new books and articles on the elements and the periodic table.

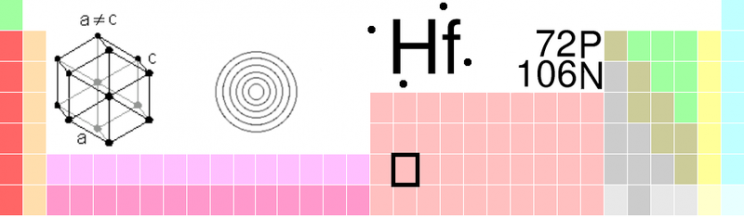

Exactly 100 years ago, in 1913, an English physicist, Henry Moseley discovered that the identity of each element was best captured by its atomic number or number of protons. Whereas the older approach had been to arrange the elements in order of increasing atomic weights, the use of Moseley’s atomic number revealed for the first time just how many elements were still missing from the old periodic table. It turned out to be precisely seven of them. Moseley’s discovery also provided a clear-cut method for identifying these missing elements through their spectra produced when any particular element is bombarded with X-ray radiation.

But even though the scientists knew which elements were missing and how to identify them, there were no shortage of priority disputes, claims, and counter-claims, some of which still persist to this day. In 1923 a Hungarian and a Dutchman working in the Niels Bohr Institute for Theoretical Physics discovered hafnium and named it after hafnia, the Latin name for the city of Copenhagen where the Institute is located. The real story, however, lies in the priority dispute that erupted initially between a French chemist Georges Urbain who claimed to have discovered this element, which he named celtium, as far back as 1911 and the team working in Copenhagen. With all the excesses of overt nationalism the British and French press supported the French claim because post-wartime sentiments persisted. The French press claimed, “Sa pue le boche” (It stinks of the Hun). The British press in slightly more restrained though no less chauvinistic terms announced that,

“We adhere to the original word celtium given to it by Urbain as a representative of the great French nation which was loyal to us throughout the war. We do not accept the name which was given it by the Danes who only pocketed the spoils of war.”

The irony was that Denmark had been neutral during the war but was presumably considered guilty by geographical proximity to Germany. Furthermore the French claim turned out to be spurious and the men from Copenhagen won the day and gained the right to name the new element after the city of its discovery.

Why are there so often priority debates in science? Generally speaking scientists have little to gain financially from their scientific discoveries. The one thing that is left to them is their ego and their claim to priority for which they will fight to the last. Another possibility is that women first discovered three or possibly four of the seven elements left to be discovered between the old boundaries of the periodic table (when it was still thought that there were just 92 elements). The three who definitely did discover elements were Lise Meitner, Ida Noddack, and Marguerite Perey from Austria, Germany, and France respectively. This is one of several areas in science where women have excelled, others being observational astronomy, research in radioactivity, and X-ray crystallography to name just a few.

One hundred years after the race began, these human stories spanning the two world wars continue to fascinate and provide new insight in the history of science.

Eric Scerri is a leading philosopher of science specializing in the history and philosophy of the periodic table. He is also the founder and editor in chief of the international journal Foundations of Chemistry and has been a full-time lecturer at UCLA for the past fourteen years where he regularly teaches classes of 350 chemistry students as well as classes in history and philosophy of science. He is the author of A Tale of Seven Elements, The Periodic Table: A Very Short Introduction, and The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image by GreatPatton, released under terms of the GNU FDL in July 2003, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Understanding the history of chemical elements appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 3/6/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

elements,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

higher education,

Science & Medicine,

this day in world history,

periodic,

atomic weight,

Dmitri Mendeleev,

John Alexander Reina Newlands,

Lothar Meyer,

Russian Chemical Society,

mendeleev,

mendeleev’s,

dmitri,

periodicity,

chemist,

style”,

History,

chemistry,

This Day in History,

periodic table,

Add a tag

This Day in World History

March 6, 1869

Mendeleev’s Periodic Table presented in public

Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev. Source: NYPL.

On March 6, 1869,

Dmitri Mendeleev’s breakthrough discovery was presented to the

Russian Chemical Society. The chemist had determined that the known elements — 70 at the time — could be arranged by their atomic weights into a table that revealed that their physical properties followed regular patterns. He had invented the periodic table of elements.

In his early twenties, Mendeleev had intuited that the elements followed some kind of order, and he spent thirteen years trying to discover it. In developing his system, he drew on the data and ideas of scientists around the world. Two — Lothar Meyer and British chemist John Alexander Reina Newlands — had published ideas about the periodicity of elements. But Mendeleev’s addressed every known element, which theirs had not.

His system also surpassed the others because he accounted for gaps in the sequence of elements. Mendeleev said that an element would be discovered to fill each gap and even predicted the properties of those elements. The discovery of the one of these missing elements — gallium, in 1875 — helped spur wide acceptance of Mendeleev’s system.

Later work showed that Mendeleev’s reliance on atomic weight to determine periodicity is not completely correct. While atomic weight tends to increase as one moves from element to element, there are exceptions. Mendeleev also did not have the theoretical understanding to explain why the elements exhibited these periodic characteristics. Nevertheless, his achievement marked an important milestone in the understanding of the physical world.

Mendeleev did not personally present his breakthrough to the Chemical Society. Ill on the day of the meeting, he asked a colleague to deliver the report.

Interestingly, the date celebrated for this event reflects Russia’s use of the “Old Style” Julian calendar. According to the “New Style” Gregorian calendar — not adopted in Russia until after 1918 — Mendeleev’s periodic table was presented twelve days later, on March 18.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.