new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: edenthorpe, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: edenthorpe in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 3/30/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

crêpe,

spelling congress,

Books,

adventure,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

word origins,

Awareness,

Fox,

etymology,

ok,

anatoly liberman,

Linguistics,

conscience,

*Featured,

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

spelling reform,

Add a tag

Preparation for the Spelling Congress is underway. The more people will send in their proposals, the better. On the other hand (or so it seems to me), the fewer people participate in this event and the less it costs in terms of labor/labour and money, the more successful it will turn out to be. The fate of English spelling has been discussed in passionate terms since at least the 1840s.

The post Etymology gleanings for March 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/24/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Dictionaries & Lexicography,

kick the bucket,

Hooligan,

Books,

love,

Language,

Oxford Etymologist,

unique,

word origins,

etymology,

ok,

anatoly liberman,

brooms,

by jingo,

split infinitives,

*Featured,

Add a tag

It is the origin of idioms that holds out the greatest attraction to those who care about etymology. I have read with interest the comments on all the phrases but cannot add anything of substance to what I wrote in the posts. My purpose was to inspire an exchange of opinions rather than offer a solution. While researching by Jingo, I thought of the word jinn/ jinnee but left the evil spirit in the bottle.

The post Etymology gleanings for February 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lauren,

on 3/23/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

US,

Dictionaries,

Dennis Baron,

A Better Pencil,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

1837,

all correct,

boston morning post,

okay,

this day in history,

ok,

history of ok,

o.k.,

oll korrect,

van buren,

william henry harrison,

Add a tag

By Dennis Baron

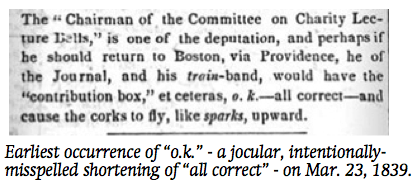

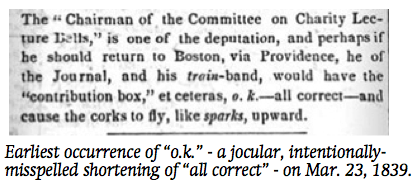

By rights, OK should not have become the world’s most popular word. It was first used as a joke in the Boston Morning Post on March 23, 1839, a shortening of the phrase “oll korrect,” itself an incorrect spelling of “all correct.” The joke should have run its course, and OK should have been forgotten, just like we forgot the other initialisms appearing in newspapers at the time, such as O.F.M, ‘Our First Men,’ A.R., ‘all right,’ O.W., ‘oll wright,’ K.G., ‘know good,’ and K.Y., ‘know yuse.’ Instead, here we are celebrating OK’s 172nd birthday, wondering why the word became a lexical universal instead of a one day wonder.

By rights, OK should not have become the world’s most popular word. It was first used as a joke in the Boston Morning Post on March 23, 1839, a shortening of the phrase “oll korrect,” itself an incorrect spelling of “all correct.” The joke should have run its course, and OK should have been forgotten, just like we forgot the other initialisms appearing in newspapers at the time, such as O.F.M, ‘Our First Men,’ A.R., ‘all right,’ O.W., ‘oll wright,’ K.G., ‘know good,’ and K.Y., ‘know yuse.’ Instead, here we are celebrating OK’s 172nd birthday, wondering why the word became a lexical universal instead of a one day wonder.

Most of the “abracadabraisms” popular among journalists in 1839 are long gone, but OK stuck around. It didn’t go viral right away, perhaps because the first virus wouldn’t be discovered for another 60 years, but unlike A.R. and K.Y., OK managed to spread beyond comic articles in newspapers, to become a word on almost everybody’s lips. For that to happen, we had to forget what OK originally meant, a jokey informal word indicating approval, and then we had to repurpose it to mean almost anything, or in some cases, almost nothing at all.

Here’s that first OK, discovered almost 50 years ago by the linguist Alan Walker Read:

he of the Journal . . . would have the “contribution box,” et ceteras, o.k.—all correct—and cause the corks to fly, like sparks, upward. [“He” is the editor of the rival Providence paper, and the subject of the article, the shenanigans of rowdy journalists and their friends, is so trivial that explaining it in no way explains OK’s success.]

The fact that the writer, the Post’s editor Charles Gordon Greene, defines OK as “all correct” confirms its novelty—readers wouldn’t be expected to know what it meant. But because readers were already used to jokey initialisms, Greene expected them to connect “oll korrect” and “all correct” on their own. He didn’t have to ask, “OK, Get it?” or add a final “Haha” to the message.

But why did OK have more staying power than yesterday’s newspaper? One thing that kept OK going after its March 23, 1839 sell-by date was its adoption by the 1940 re-election campaign of Pres. Martin Van Buren. Van Buren, born in Kinderhook, New York, was known as Old Kinderhook, and his political machine operated out of New York’s O.K. (Old Kinderhook) Democratic Club. The coincidence between “Old Kinderhook” and “oll korrect” proved a sloganeer’s dream, as this notice for a political rally illustrates:

The Democratic O.K. Club are hereby ordered to meet at the House of Jacob Colvin. [1840, Oxford English Dictionary, known more commonly by the initialism OED]

That campaign may have helped OK more than it helped Van Buren, who was definitely not OK: he was blamed for the financial crisis of 1837 and roundly trounced in the election by William Henry Harrison. Harrison himself wasn’t so OK: he died from pneumonia a month after giving a 2-hour inaugural address in the rain, but OK got national exposure, and it was soon tapped as one of many shorthand expressions (like gmlet for ‘give my love to’) serving the new telegraph, the “Victorian internet” that began spre

By: Lauren,

on 11/23/2010

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

allan metcalf,

american dialect society,

metcalf,

Lexicography,

okay,

little women,

ok,

word history,

andrew jackson,

etmology,

Add a tag

Some books are amazing, and some are not, and some are OK. (Yes, I can make bad jokes like this all day, and I shall.) Below is a Q&A with author Allan Metcalf about his book OK: The Improbable Story of America’s Greatest Word. Metcalf is also Professor of English at MacMurray College, Executive Secretary of the American Dialect Society, and punnier than I can ever hope to be. -Lauren Appelwick, Blog Editor

Q. Why write a whole book about OK? I mean, it’s just…OK.

A. Ah, but it’s OK the Great: the most successful and influential word ever invented in America. It’s our most important export to languages around the world—best known and most used, though used sometimes in weird ways. It expresses the pragmatic American outlook on life, the American philosophy if you will, in two letters. And in the twenty-first century, inspired by the 1967 book title I’m OK, You’re OK (which is the only famous quotation involving OK), it also has taught us to be tolerant of those who are different from us. On top of all that, its origin almost defies belief (it was a joke misspelling of “all correct”) and its survival after that inauspicious origin was miraculous. And strangely, though we use it all the time, we carefully avoid it when we’re making important documents and speeches. So, wouldn’t you say OK deserves a book?

Q. Then why hasn’t someone written an “OK” book before?

A. Good question. The answer goes back to your first question—it’s just OK. It’s so ordinary, so common nowadays that we use it without thinking. And its meaning is lacking in passion, so it doesn’t seem very interesting. But that’s just what is interesting. OK is a unique way to indicate approval without having to approve. If we want to express enthusiasm when using OK, we have to add something, like an A or an exclamation mark, AOK or OK! The neutrality of OK is incredibly useful, but it doesn’t catch our attention, and so there has been no previous book. Mine is a wake-up call, I hope.

Now although there haven’t been books, there have been articles aplenty about OK. But they mostly deal with the origins of OK, and they are mostly wrong. The true beginning of OK is truly improbable.

Q. OK, so why are so many explanations wrong? And what is the true origin?

A. Very soon after the birth of OK, its origins were deliberately misidentified, and for more than a century etymologists were led astray by that red herring. It was only in the 1960s that a scholar of American English, Allen Walker Read, did the research and published the detailed evidence that shows beyond a doubt—

Q. What?

A. That OK began as a joke in the Boston Morning Post of Saturday, March 23, 1839. As Read demonstrated, the Post’s o.k., which was explained to mystified readers as an abbreviation for “all correct,” was just one of numerous joking abbreviations employed by Boston newspaper editors to enliven their stories, two others being “o.f.m.” for “our first men” and “o.w.” for “all right.”

Q. So how come nobody remembered that explanation?

A. Because other explanations sprang up before OK was a year old.

One explanation was true, as far as it goes. Martin Van Buren was running for reelection as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States. Well, it happens that his hometown was Kinderhook, New York, so in the election year 1840 his supporters began to call

By: Stephanie,

on 5/7/2008

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford,

A-Featured,

Oxford Etymologist,

Lexicography,

Old,

oupblog,

Jackson,

english,

Andrew,

etymologist,

Anatoly,

Liberman,

OUP,

etymology,

ok,

oll,

korrect,

Kinderhook,

Blog,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

All those who pose as experts in etymology tend to receive questions about certain popular words, with exotic slang and obscenities attracting the greatest attention. (The F-word is at the top of the list. Is it an acronym? No, it is not.) Beginning with my old post on copasetic, I tried to anticipate some such questions, and for a long time I have been wondering how to tell the story of OK, an object of undying interest. The excitement of this oft-repeated story has long since worn off, and only the thought that perhaps I can add nuance (as highbrows say) to the OK epic and thus partly avoid the otherwise inevitable triviality allows me to continue.

OK has been traced to numerous languages, including, Classical Greek, Finnish, Choctaw, Burmese, Irish, and Black English (Black English caught the fancy of many journalists, who in the sixties “rediscovered” Africa without going there and gained the reputation of radicals at no cost). The literature is also full of suggestions that the sources of OK have to be sought in German, French, or Danish. This guessing game presents interest for two reasons. First, it shows that many people do not realize the importance of research in historical linguistics. Not only do they risk offering conjectures without as much as a cursory look at the evidence: they do not even take the trouble to get acquainted with the views of their equally uninformed predecessors. One constantly runs into statements like: “I am surprised that it has not occurred to anyone…”, whereupon an etymology follows that was offered fifty years earlier and rehashed again and again. (Compare the review I once read of a performance of The Swan Lake. The reviewer said that this was the best performance of the ballet he could remember. I concluded that it was either the first time he had seen The Swan Lake or that he suffered from amnesia.) In my database, I have 78 citations for OK, mainly from the press, and this number could have been doubled or tripled if I had made the effort to collect all the letters on the subject printed in newspapers; I availed myself of only some of them. Variations on the same hypotheses keep surfacing again and again. Second, even specialists may not always realize that in dealing with a word like OK, a plausible derivation presupposes two steps. OK spread through the United States like wildfire in the early 1840’s and stayed. Regardless of whether the lending language is believed to be Choctaw or Finnish, the etymologist has to explain why OK became popular when it did. A similar approach is required for all slang and for many stylistically neutral words. Any innovation, be it bikini, recycling, a redistribution of voting districts, or a neologism, comes from a smart individual and is either rejected or accepted by the public. If a word has been rejected, we usually know little or nothing about its history (a stillborn has a short biography). But if it has survived, we should explain where it originated and what contributed to its longevity. Suppose OK is Greek. Why then was its radiation center the United States? And why in the forties of the 19th century? No etymology of OK will be valid while such questions remain unanswered.

In our case, the answers are known. Today we confuse one another with cryptic acronyms like LOL “laugh out loud” and AWOL (here a gloss is not needed). Linguistic tastes do not seem to have changed since the 1830’s. Facts give credence to the belief that OK stands for oll korrect, but not to the legend that this was the spelling used by Andrew Jackson. Although the 7th President of the United States would not have been hired as a spelling master even by a rural school, anecdotes about his gross illiteracy have little foundation in fact. The craze for k, as it was called (Kash, Kongress, and so forth), added to the staying power of the abbreviation OK. But OK would probably have disappeared along with dozens of others if it had not been used punningly by the supporters of Van Buren, the next president, born in Old Kinderhook, New York. To be sure, it could still have vanished once the campaign was over, but it did not. It even became the most famous American coinage, understood far beyond the borders of the United States. This is the account one finds in dictionaries, but dictionaries, quite naturally, do not dwell on the history of the search, which entailed decades of studying documents, broken friendships, and the making of a great reputation.

It was Allen Walker Read who reconstructed the Old Kinderhook link in the rise of OK, and his discovery became a sensation: first The Saturday Review published an article by him (1941), and years later an interview devoted to OK appeared in New Yorker. Read is also the author of many other excellent works, but few people outside academia have heard about them. At the end of one of his article on OK (he brought out four major articles on the subject and several addenda, all of them published in the journal American Speech), Read expressed his surprise that the origin of OK, which everybody must have known in Van Buren’s days, was forgotten so soon. However, the case is not unique. People regularly forget the pronunciations that were current only a generation ago and the events that led to the coining of words.

Read had to dispose of the possible pre-1839 existence of OK. And this is where personal animosities came in. One of the editors of the Dictionary of American English was Woodford A. Heflin, an excellent specialist, whose contributions clarified a good deal in the emergence of OK. But he put too much trust in the following line found in the journal of William Richardson, a businessman from Boston. In his detailed description of a journey to New Orleans (1815), Richardson wrote: “Arrived in Princeton, a handsome little village, 15 miles from N Brunswick, ok & at Trenton, where we dined at 1 P.M.” The ok & part makes no sense. Richardson may have begun a sentence that he did not finish, or a scribal error may have occurred. The amount of interlining and correction in the manuscript is considerable. Even if the sentence can be understood without emendation, the mysterious ok need not mean what it means to us, for the well-educated Richardson would hardly have infused a piece of low slang after mentioning N Brunswick. This was Read’s conclusion, but Heflin insisted that the 1815 occurrence of OK was the earliest we have. The strife that ensued soured the relations between the two scholars. Heflin went public and fought what he called an incorrect etymology of OK in the pages of American Speech. Read responded (the journal showed laudable impartiality and let both opponents express their views). The battle was fought in the sixties, long after Read’s initial article appeared in The Saturday Review.

Read examined the manuscript of Richardson’s journal, but to the best of my knowledge, he never mentioned the fact that he had not done it alone. This is what Frederic C. Cassidy wrote in 1981 (American Speech 56, 1981, p. 271): “After many attempts to track down the diary, Read and I at last discovered that it is owned by the grandson of the original writer, Professor L[awrence] Richardson, Jr., of the Department of Classic Studies at Duke University. Through his courtesy we were able to examine this manuscript carefully, to make greatly enlarged photographs of it, and to become convinced (as is Richardson) that, whatever the marks in the manuscript are, they are not OK. The Richardson diary does not constitute evidence for the currency of OK before 1839.” What an anticlimax! I only don’t understand why Read did not say all of it himself. In 1981 he was an active scholar guarding his priority most carefully, and there is no doubt that if Cassidy’s report had not been accurate, he would have made his disagreement known.

Here ends my story of OK, nuance and all.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as

An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins,

The Oxford Etymologist, appears here each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to

[email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

ShareThis

By: Rebecca,

on 11/6/2007

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Law,

Education,

Politics,

Philosophy,

oxford,

privacy,

A-Featured,

james,

rule,

oupblog,

edenthorpe,

sutter,

automating,

pupils,

whereabouts,

peril,

b,

bush,

Add a tag

James B. Rule, author of Privacy in Peril: How We are Sacrificing a Fundamental Right in Exchange for Security and Convenience is Distinguished Affiliated Scholar at the Center for the Study of Law and Society at the University of California, Berkeley and a former fellow of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. He is also a winner of the C. Wright Mills Award. Privacy in Peril looks at the legal ways in which our private data is used by the government and private industry. In the original article below Rule looks at a seemingly innocuous effort to track schoolchildren and the issues it raises.

If you increasingly feel that information about your life is taking on a life of its own—collected, monitored, transmitted and used by interests outside your control—you’re probably not paranoid.

A recent story in Information Week tells of a school in Edenthorpe, England, that is experimenting with electronic tracking of its pupils. The idea is to fit their clothing with RFID tags—tiny radio transmitters—that can enable school authorities to monitor people’s whereabouts throughout the school day. RFID technology is already widely in use by retailers to track merchandise within shops and, some suspect, after purchase by customers. (more…)

Share This