By Anatoly Liberman

I am impressed.

Not long ago I asked two riddles. Who coined the phrase indefatigable assiduity and who said that inspiration does not come to the indolent? The phrase with assiduity turns up on the Internet at once (it occurs in the first chapter of The Pickwick Papers), but John Cowan pointed out that Dickens may have used (parodied?) a popular cliché of that time. I believed that the phrase was his invention. Apparently, it was not. But the second riddle seemed insoluble to me. Here I was also mistaken. Only the god Odin (about whom more “anon”) knew the riddle that no one could answer. Yes, indeed, it was Tchaikovsky who said so (in Russian: “Vdokhnoven’e—gost’ia, kotoraia ne iavliaetsia k lenivym”). My second source of surprise was Stephen Goranson’s comment. In the same post, I mentioned two reviews of Talbot’s book English Etymologies. As a matter of fact, I knew three but forgot about the third. I culled the reviews from Arnold’s biography of Talbot and from Arthur G. Kennedy’ bibliography of writings on the English language. However, Goranson discovered a bunch of other reviews. Although I am used to getting all kinds of recondite information from him, I was impressed. For years my humble wish has been to find an antedating for the OED and an item missed by Kennedy. So far I have succeeded only in the second endeavor (but even that only because he did not screen the myriad tiny publications and fugitive journals I used for my work). With Goranson such miracles happen every day. I dare not ask how he manages to do it.

An old debt.

In my January gleanings, I promised to return to the mail I received after my latest talk show on Minnesota Public Radio. The theme was buzzwords and hackneyed phrases. I have already had a chance to note that very many people are disgusted with the gratuitous use of important sounding clichés, meaningless adverbs, and silly circumlocutions. Yet the world does not heed their disgust. Here is a short list of the words and phrases the listeners despise: kick the can down the road (politicians have indeed almost kicked this battered can to its ultimate destination), no boots on the ground (a colorful phrase, but if you rub it in ten times a day, the color loses its luster), ratchet up (for instance, the pressure; I agree: just as people have substituted morph for change, impact for influence, and utilize for use, they have discarded increase ~ decrease and constantly ratchet things up and down—a technical term has broken loose like a tiger from a Zoo in India and spares no one on its way), granular (that is, “detailed”; a tasteless metaphor no one needs), cascading “arranged in a sequence” (a pretentious, florid metaphor), conscience laundering (when a guilt-ridden wealthy person makes a charitable investment; the reference and the irony are obvious, and the phrase may perhaps be allowed to survive as an insipid joke unless those who like to kick the can down the road decide to love it to death), folks (when people in high positions strike a “folksy” attitude but end up sounding condescending), the horrible word selfie (this one will, most likely, lose its charm with age), suspicious blends like sharknado, and the much-denigrated but indestructible adverb literally. “It is what it is” (another phrase one of our listeners hates).

Below I will quote part of a letter I received:

“I wanted to ask your opinion concerning a new turn of phrase I’ve been hearing much used by radio and television reporters. It is an existential threat. I can’t hear the phrase without thinking of adversaries throwing remaindered copies of Sartre and Camus at each other and I run for a dictionary to steady myself and remind myself of what existential means. This use, paired always with threat, seems very odd to me. Can you explain it to me?”

I have heard this phrase so many times that I am no longer afraid. Existential threat is obviously a threat to (our) existence. It seems to be a typical felicity of speech invented by journalists, who always try to say something striking and memorable. Danger or even great danger may not frighten you enough, but existential threat is sure to send shivers up or rather down your spine.

Back to Medieval Scandinavia

1. Does balderdash have anything to do with the name of the god Baldr (usually written as Balder in English)? No, it does not. Balder was the most beautiful god of them all, but fate decreed that he should be killed. His death showed that the gods were not immortal, and everything they tried to do after the heinous murder of their favorite went wrong. Almost exactly two years ago, I wrote a post on balderdash (15 February 2012). There more can be found about this enigmatic word.

2. The tree Yggdrasill. A question about this name was sent by a well-informed reader. I know both sources he mentioned. The exact meaning of Yggdrasill is debatable. At some time, speakers understood it as a synonym for the world tree, but Yggdrasill seems to have been the most ancient name of Odin: ygg- “fear, terror” and -drasill “horse.” There is good reason to believe that at a very early stage in his career Odin was thought of as a horse god (not a protector of horses but a theriomorphic deity, half-horse, half-man, a centaur-like creature). If our correspondent is interested in details, he will find a detailed discussion of this myth and the name in my article published in the periodical NOWELE (= North-Western European Language Evolution) 62, 2011, 351-430. The root of drasill is dras, so that dra- cannot be abstracted from it. The word has no Baltic or Finno-Ugric cognates.

Ketchup.

Is this a Malayan word? Since A Bibliography of English Etymology does not grace the shelves of every public library, here are the relevant titles borrowed from it. Several publications appeared in Notes and Queries: vol. 1, 1849-50, p. 124; Series 4/IX, p. 279, Series7 /V, 1888, 475-476, and 7/VI, p.12 (the latter by Skeat; the older issues of this periodical are available online); The Babylonian & Oriental Record, vol. 3, 1889, 284-286; The Academy, vol. 36, 1889, pp. 358-359; and Manchester (City News) Notes and Queries, vol.7, 1890, No. 3, p.42. The OED states that the word is Chinese. But while dealing with the vocabulary current in that area and borrowed into English, linguists often have trouble deciding which language is the source of the English word. The article by Anthea Fraser Gupta “English Words from the Malay World” (Notes and Queries, vol. 253, 2008, 357-360) deals with this question in considerable detail. Ketchup is not mentioned in it.

The origin of bind “complain” (slang).

I do not know its origin and have not read anything about it. This sense of the verb bind seems to have originated in England, among pilots, so it is a RAF word (like gremlin, discussed in this blog not long ago). Since initially it could be used transitively (to bind someone), the development may have been from “fasten” (suggesting that one is in a bind and needs help?) and then “keep nagging and thus tie oneself to the other party; complain.” But without records of those intermediate steps, this is unprofitable guesswork. Since bitch “complain” had already existed by the early forties, bitching and binding, an alliterative phrase, naturally suggested itself. Perhaps specialists in slang among our correspondents are in a position to offer help, and, if I may again paraphrase The Pickwick Papers, provide us with the first ray of light which will illuminate the gloom and convert into a dazzling brilliance the obscurity in which the history of bind is now enveloped.

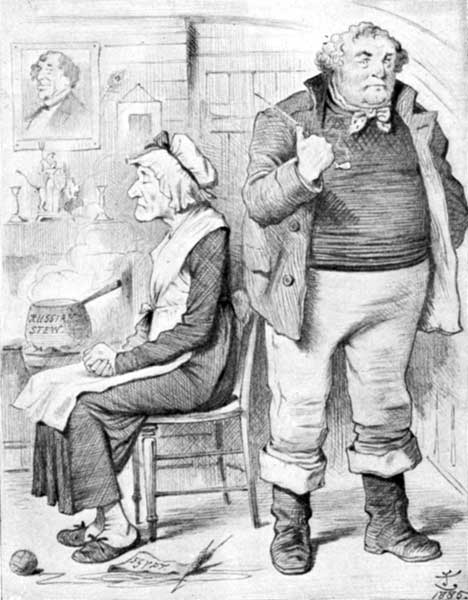

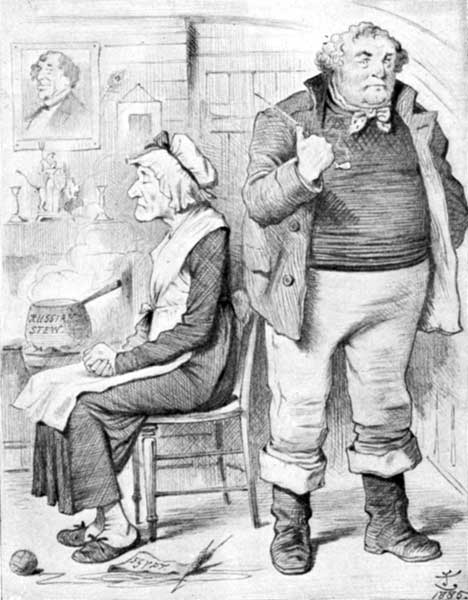

Here is Mrs. Gummidge, the world-famous specialist in bickering and binding

Why are there dialects in which got and hot do not rhyme?

While discussing horse and hoarse, I noted that one can often find a conservative or an advanced dialect in which the pronunciation differs from the Standard. Hot and got go back to dissimilar forms. The Old English for hot was hat, with long a (as in Modern Engl. father or spa). Conversely, got has always had short o. In Middle English, long a changed to long o (approximately as in Modern Engl. law or more), and one could expect Modern Engl. hote. Modern o in hot is believed to have been borrowed from the comparative and the superlative degree (hotter, hottest), in which long o was shortened. This is how the vowels of hot and got merged. But in such situations some dialects may prefer to obstruct the merger and keep the actors (vowels or consonants) apart. Therefore, we have areas in which the reflexes of shortened long o and the original short o still differ.

Chance coincidences.

In one of the letters I received, our correspondent asks whether certain relations between and among the words he detected might be real. For example, can grig, creek, and eel be cognates? Could ci-, the first syllable of Italian ciba “food,” be related to the syllable gi-, the beginning of the word for “earth,” and so forth? Yes, they could, but they are not. Similar ideas occurred to many people since at least Plato’s time, but especially in the Middle Ages. Sound symbolism and later associations often lead us astray. Every word has a history, and without knowing it, no etymology will achieve convincing results. Even Latin luna and Engl. moon are unrelated.

A few more questions will have to wait until the end of March. Here I would like to thank all those who direct my attention to various websites, whether dealing with word origins or Talbot’s achievements in photography. I follow every tip, and nothing our correspondents suggest is wasted, even if I do not always use their material in my posts.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: THE POLITICAL MRS. GUMMIDGE. (The finished Sketch by Sir John Tenniel for the “Punch” Cartoon, 2nd May, 1885. By Permission of Gilbert E. Samuel, Esq.) via Project Gutenberg.

The post Monthly gleanings for February 2014 appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anatoly Liberman

A Happy New Year to our readers and correspondents! Questions, comments, and friendly corrections have been a source of inspiration to this blog throughout 2012, as they have been since its inception. Quite a few posts appeared in response to the questions I received through OUP and privately (by email). As before, the most exciting themes have been smut and spelling. If I wanted to become truly popular, I should have stayed with sex, formerly unprintable words, and the tough-through-though gang. But being of a serious disposition, I resist the lures of popularity. It is enough for me to see that, when I open the page “Oxford Etymologist,” the top post invites the user to ponder the origin of fart. And indeed, several of my “friends and acquaintance” (see the previous gleanings) have told me that they enjoy my blog, but invariably added: “I have read your post on fart. Very funny.” I remember that after dozens of newspapers reprinted the fart essay, I promised a continuation on shit. Perhaps I will keep my promise in 2013. But other ever-green questions also warm the cockles of my heart, especially in winter. For instance, I never tire of answering why flammable means the same as inflammable. Why really? And now to business.

Folk etymology. “How much of the popular knowledge of language depends on folk etymology?” I think the question should be narrowed down to: “How often do popular ideas of language depend on folk etymology?” People are fond of offering seemingly obvious explanations of word origins. Sometimes their ideas change a well-established word. Shamefaced, to give just one example, developed from shame-fast (as though restrained by shame). Some mistakes are so pervasive that one day the wrong forms may share the fate of shame-fast. Such is, for example, protruberance, by association with protrude. Despite what the OED says, it seems more probable that miniscule developed from minuscule only because the names of mini-things begin with mini-. Incidentally, from a historical point of view, even miniature has nothing to do with the picture’s small size. Most people would probably say that massacre has the root mass- (“mass killing”), but the two words are not connected. Anyone can expand this list.

Sound symbolism. A correspondent has read my book on word origins and came across a section on words beginning with gr-, such as Grendel and grim. Since they often refer to terror and cruelty (at best they designate gruff and grouchy people), he wonders how the word grace belongs here. It does not. Sound symbolism is a real force in language. One can cite any number of words with initial gl- for things glistening and gleaming, with fl- when flying, flitting, and flowing are meant, as well as unpleasant sl-words like slimy and sleazy. But green, flannel, and slogan will show that at best we have a limited tendency rather than a rule. Besides, many sound symbolic associations are language-specific. So somebody who has a daughter called Grace need not worry.

Grendel attacking Three Graces.

Engl. galoot and Catalan golut. More than four years ago, I wrote a triumphant post on the origin of Engl. galoot. The reason for triumph was that I was the first to discover the word’s derivation (a memorable event in the life of an etymologist). Just this month one of our correspondents discovered that post and asked about its possible connection with Catalan golut “glutton; wolverine.” This, I am sure, is a coincidence. In the Romance languages, we find words representing two shapes of the same root, namely gl- and gl- with a vowel between g and l. They inherited this situation from Latin: compare gluttire “to swallow” and gola “throat.” English borrowed from Old French and later from Latin several words representing both forms of the root, as seen in glut ~ glutton and gullet. As for the sense “wolverine” (the name of a proverbially voracious animal, Gulo luscus), it has also been recorded in English. By contrast, Engl. galoot has not been derived from the gl- root, with or without a vowel in the middle. It goes back to Dutch, while the Dutch took it over from Italian galeot(t)o “sailor” (which is akin to galley).

Judgement versus judgment. This is an old chestnut. Both spellings have been around for a long time. Acknowledgment and abridgment belong with judgment. Since the inner form of all those word is unambiguous, the variants without e cause no trouble. The widespread opinion that judgment is American, while judgement is British should be repeated with some caution, because the “American” spelling was at one time well-known in the UK. However, it is true that modern American editors and spellcheckers require the e-less variant. I would prefer (though my preference is of absolutely no importance in this case) judgement, that is, judge + ment. The deletion of e produces an extra rule, and we have enough of silly spelling rules already. Another confusing case with -dg- is the names Dodgson and Hodgson. Those bearers of the two names whom I knew pronounced them Dodson and Hodson respectively, but, strangely, many dictionaries give only the variant with -dge-. Is it known how Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, pronounced his name?

Zigzag and Egypt. The tobacco company called its products Zig-Zag after the “zigzag” alternating process it used, though it may have knowingly used the reference to the ancient town Zig-a-Zag (I have no idea). Anyway, the English word does not have its roots in the Egyptian place name.

Lark. I was delighted to discover that someone had followed my advice and listened to Glinka-Balakirev’s variations. It is true that la-la-la does not at all resemble the lark’s trill, and this argument has been used against those who suggested an onomatopoeic origin of the bird’s name. But, as long as the bird is small, la seems to be a universal syllable in human language representing chirping, warbling, twittering, trilling, and every other sound in the avian kingdom. It was also a pleasure to learn that specialists in Frisian occasionally read my blog. I know the many Frisian cognates of lark thanks to Århammar’s detailed article on this subject (see lark in my bibliography of English etymology).

Bumper. I was unable to find an image of the label used on the bottles of brazen-face beer. My question to someone who has seen the label: “Was there a picture of a saucy mug on it?” (The pun on mug is unintentional.) I am also grateful for the reference to the Gentleman’s Magazine. My database contains several hundred citations from that periodical, but not the one to which Stephen Goranson, a much better sleuth that I am, pointed. This publication was so useful for my etymological bibliography that I asked an extremely careful volunteer to look through the entire set of Lady’s Magazine and of about a dozen other magazines with the word lady in the title. They were a great disappointment: only fashion, cooking, knitting, and all kinds of household work. Women did write letters about words to Notes and Queries, obviously a much more prestigious outlet. However, we picked up a few crumbs even from those sources. The word bomber-nickel puzzled me. I immediately thought of pumpernickel but could not find any connection between the bread and the vessel discussed in the entry I cited. I still see no connection. As for pumpernickel, I am well aware of its origin and discussed it in detail in the entry pimp in my dictionary (pimp, pump, pomp-, pumper-, pamper, and so forth).

Again. It was instructive to see the statistics about the use of the pronunciation again versus agen and to read the ditty in which again has a diphthong multiple times. If I remember correctly, Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, and others rhymed again only with words like slain, though one never knows to what extent they exploited the so-called rhyme to the eye. Most probably, they did pronounce a diphthong in again.

Scots versus English, as seen in 1760 (continued from the previous gleanings).

- Sc. fresh weather ~ Engl. open weather

- Sc. tender ~ Engl. fickly

- Sc. in the long run ~ Engl. at long run

- Sc. with child to a man ~ Engl. with child by a man (To be continued.)

Happy holidays! We’ll meet again in 2013.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Three Graces, 1531. The Louvre via Wikimedia Commons. (2) An illustration of the ogre Grendel from Beowulf by Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall in J. R. Skelton’s Stories of Beowulf (1908) via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for December 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of

Anatoly Liberman is the author of