By Anatoly Liberman

A Happy New Year to our readers and correspondents! Questions, comments, and friendly corrections have been a source of inspiration to this blog throughout 2012, as they have been since its inception. Quite a few posts appeared in response to the questions I received through OUP and privately (by email). As before, the most exciting themes have been smut and spelling. If I wanted to become truly popular, I should have stayed with sex, formerly unprintable words, and the tough-through-though gang. But being of a serious disposition, I resist the lures of popularity. It is enough for me to see that, when I open the page “Oxford Etymologist,” the top post invites the user to ponder the origin of fart. And indeed, several of my “friends and acquaintance” (see the previous gleanings) have told me that they enjoy my blog, but invariably added: “I have read your post on fart. Very funny.” I remember that after dozens of newspapers reprinted the fart essay, I promised a continuation on shit. Perhaps I will keep my promise in 2013. But other ever-green questions also warm the cockles of my heart, especially in winter. For instance, I never tire of answering why flammable means the same as inflammable. Why really? And now to business.

Folk etymology. “How much of the popular knowledge of language depends on folk etymology?” I think the question should be narrowed down to: “How often do popular ideas of language depend on folk etymology?” People are fond of offering seemingly obvious explanations of word origins. Sometimes their ideas change a well-established word. Shamefaced, to give just one example, developed from shame-fast (as though restrained by shame). Some mistakes are so pervasive that one day the wrong forms may share the fate of shame-fast. Such is, for example, protruberance, by association with protrude. Despite what the OED says, it seems more probable that miniscule developed from minuscule only because the names of mini-things begin with mini-. Incidentally, from a historical point of view, even miniature has nothing to do with the picture’s small size. Most people would probably say that massacre has the root mass- (“mass killing”), but the two words are not connected. Anyone can expand this list.

Sound symbolism. A correspondent has read my book on word origins and came across a section on words beginning with gr-, such as Grendel and grim. Since they often refer to terror and cruelty (at best they designate gruff and grouchy people), he wonders how the word grace belongs here. It does not. Sound symbolism is a real force in language. One can cite any number of words with initial gl- for things glistening and gleaming, with fl- when flying, flitting, and flowing are meant, as well as unpleasant sl-words like slimy and sleazy. But green, flannel, and slogan will show that at best we have a limited tendency rather than a rule. Besides, many sound symbolic associations are language-specific. So somebody who has a daughter called Grace need not worry.

Grendel attacking Three Graces.

Engl. galoot and Catalan golut. More than four years ago, I wrote a triumphant post on the origin of Engl. galoot. The reason for triumph was that I was the first to discover the word’s derivation (a memorable event in the life of an etymologist). Just this month one of our correspondents discovered that post and asked about its possible connection with Catalan golut “glutton; wolverine.” This, I am sure, is a coincidence. In the Romance languages, we find words representing two shapes of the same root, namely gl- and gl- with a vowel between g and l. They inherited this situation from Latin: compare gluttire “to swallow” and gola “throat.” English borrowed from Old French and later from Latin several words representing both forms of the root, as seen in glut ~ glutton and gullet. As for the sense “wolverine” (the name of a proverbially voracious animal, Gulo luscus), it has also been recorded in English. By contrast, Engl. galoot has not been derived from the gl- root, with or without a vowel in the middle. It goes back to Dutch, while the Dutch took it over from Italian galeot(t)o “sailor” (which is akin to galley).

Judgement versus judgment. This is an old chestnut. Both spellings have been around for a long time. Acknowledgment and abridgment belong with judgment. Since the inner form of all those word is unambiguous, the variants without e cause no trouble. The widespread opinion that judgment is American, while judgement is British should be repeated with some caution, because the “American” spelling was at one time well-known in the UK. However, it is true that modern American editors and spellcheckers require the e-less variant. I would prefer (though my preference is of absolutely no importance in this case) judgement, that is, judge + ment. The deletion of e produces an extra rule, and we have enough of silly spelling rules already. Another confusing case with -dg- is the names Dodgson and Hodgson. Those bearers of the two names whom I knew pronounced them Dodson and Hodson respectively, but, strangely, many dictionaries give only the variant with -dge-. Is it known how Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, pronounced his name?

Zigzag and Egypt. The tobacco company called its products Zig-Zag after the “zigzag” alternating process it used, though it may have knowingly used the reference to the ancient town Zig-a-Zag (I have no idea). Anyway, the English word does not have its roots in the Egyptian place name.

Lark. I was delighted to discover that someone had followed my advice and listened to Glinka-Balakirev’s variations. It is true that la-la-la does not at all resemble the lark’s trill, and this argument has been used against those who suggested an onomatopoeic origin of the bird’s name. But, as long as the bird is small, la seems to be a universal syllable in human language representing chirping, warbling, twittering, trilling, and every other sound in the avian kingdom. It was also a pleasure to learn that specialists in Frisian occasionally read my blog. I know the many Frisian cognates of lark thanks to Århammar’s detailed article on this subject (see lark in my bibliography of English etymology).

Bumper. I was unable to find an image of the label used on the bottles of brazen-face beer. My question to someone who has seen the label: “Was there a picture of a saucy mug on it?” (The pun on mug is unintentional.) I am also grateful for the reference to the Gentleman’s Magazine. My database contains several hundred citations from that periodical, but not the one to which Stephen Goranson, a much better sleuth that I am, pointed. This publication was so useful for my etymological bibliography that I asked an extremely careful volunteer to look through the entire set of Lady’s Magazine and of about a dozen other magazines with the word lady in the title. They were a great disappointment: only fashion, cooking, knitting, and all kinds of household work. Women did write letters about words to Notes and Queries, obviously a much more prestigious outlet. However, we picked up a few crumbs even from those sources. The word bomber-nickel puzzled me. I immediately thought of pumpernickel but could not find any connection between the bread and the vessel discussed in the entry I cited. I still see no connection. As for pumpernickel, I am well aware of its origin and discussed it in detail in the entry pimp in my dictionary (pimp, pump, pomp-, pumper-, pamper, and so forth).

Again. It was instructive to see the statistics about the use of the pronunciation again versus agen and to read the ditty in which again has a diphthong multiple times. If I remember correctly, Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, and others rhymed again only with words like slain, though one never knows to what extent they exploited the so-called rhyme to the eye. Most probably, they did pronounce a diphthong in again.

Scots versus English, as seen in 1760 (continued from the previous gleanings).

- Sc. fresh weather ~ Engl. open weather

- Sc. tender ~ Engl. fickly

- Sc. in the long run ~ Engl. at long run

- Sc. with child to a man ~ Engl. with child by a man (To be continued.)

Happy holidays! We’ll meet again in 2013.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Three Graces, 1531. The Louvre via Wikimedia Commons. (2) An illustration of the ogre Grendel from Beowulf by Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall in J. R. Skelton’s Stories of Beowulf (1908) via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for December 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anatoly Liberman

Some time ago, I devoted three posts to alcoholic beverages: ale, beer, and mead. It has occurred to me that, since I have served drinks, I should also take care of wine glasses. Bumper is an ideal choice for the beginning of this series because of its reference to a large glass full to overflowing. It is a late word, as words go: no citation in the OED predates 1677. If I am not mistaken, the first lexicographer to include it in his dictionary was Samuel Johnson (1755). For a long time bumper may have been little or not at all known in polite society. Even Nathan Bailey (1721 and 1730) missed it. But once it surfaced in dictionaries, guesswork about its origin began.

Johnson derived bumper from bum “being prominent.” Etymology was not his forte (to put it mildly), and the source of the consonant p hardly bothered him. Of the revisions of Johnson’s work especially serious was the one by the Reverend H. J. Todd (1827). Although later scholars derided Todd’s etymologies, his explanations were not always useless, despite the fact that he had no notion of the progress historical linguistics had made by 1827. Be that as it may, to discover the origin of seventeenth-century English slang (and I assume bumper was slang), one can dispense with the facts of Indo-European and even of Old English. Todd called Johnson’s conjecture far-fetched, offered none of his own, and only said that others had traced bumper to bumbard ~ bombard. It is most irritating that he did not indicate who the “others” were. I have been unable to find his authority and will be very pleased if someone enlightens me on this point.

Bombard, a word known to Shakespeare and his contemporaries, meant “cannon” and (on account of its size or form?) “leather jug or bottle for liquor.” For a long time Skeat had sufficient trust in this etymology. Bumper, he said, appeared in English just as the older bombard, a drinking vessel, disappeared and was “a corruption of it.” This hypothesis fails to convince. A jug or a bottle for liquor is not a glass, and it remains unclear why a word, evidently in common use, should have been “corrupted.” Nevertheless, the bombard-bumper etymology appeared in numerous good dictionaries, though, surprisingly, Skeat’s early competitors Eduard Mueller and Hensleigh Wedgwood passed by the word.

Then there were attempts to present bumper as a disguised compound. Such an idea should not be dismissed out of hand. For example, bridal, now understood as an adjective, derives from Old Engl. bryd “bride” and ealu “ale” and meant “ale drinking at a wedding feast.” The indefatigable Charles Mackay, who traced hundreds of English words to Irish Gaelic, explained bumper as the sum of bun “bottom” and barr “top”: bum-barr or bun-parr “full from the bottom to the top.” A somewhat more reasonable theory looked upon bumper as a borrowing from French and decomposed it into bon “good” and père or Père “father.” A typical statement ran as follows: “When the English were good Catholics, they usually drank the Pope’s health in a full glass after dinner—Au bon Père—whence your bumper.” Perhaps this derivation was first offered in Joseph Spence’s posthumous (1820) Anecdotes, Observations, and Characters, of Books and Men…, an amusing and entertaining book. Spence had no idea when bumper surfaced in English and did not doubt that at the time of the word’s appearance the English were still good Catholics. Nor did he provide any evidence that the rite he mentioned ever existed. (Those with a taste for such reading will also enjoy Samuel Pegge’s Anecdotes of the English Language…, 1844.)

This is a country bumpkin. Bumpkin and bumper are not related.

Soon after the publication of Spence’s

Anecdotes Alexander Henderson brought out a volume titled

The History of Ancient and Modern Wines (1824), a learned and eminently readable piece of scholarship. Like many of his contemporaries, he occasionally dabbled in etymology. According to him,

bumper was “a slight corruption of the old French phrase

bon per, signifying a boon companion.” Granted, French

pair “one’s equal, peer” had the form

per in Old French, but where did Henderson find the collocation

bon per “boon companion”? This is the problem with both Mackay and the adherents of the French theory. The etymons they posed do not and did not exist in the alleged lending languages, so that, following their logic, the phrases had to be coined in English from two foreign elements, change their shape, merge, and become opaque simplexes. This chain of events defies belief.

Not unexpectedly, some people thought they had found a tie between bumper and bump up, a rather rare collocation meaning “swell up.” The glass was said to be filled so as to cause the liquid to “bump up” slightly above the rim. Several variations on the bump up theme exist. At this point I need a short digression. Some etymological dictionaries have been written by monomaniacs, as Ernest Weekley called them. They derived all the words of English from several ancient roots or from a few primordial cries, or from one language (Irish Gaelic, Arabic, Hebrew, etc.). Criticizing their labors is a thankless task. By contrast, the authors of some dictionaries were so misguided, even if learned, that one wonders how they managed to produce their monstrosities. One such monster is Words: Their History and Derivation, Alphabetically Arranged by Dr. F. Ebener and E.M. Greenway, Jr. (Baltimore and London, 1871). Greenway was, apparently, the translator of this hapless work from German, while Ebener may have been a medical doctor. Among the physicians of the past one can find several crazy etymologists. The dictionary caused such an outcry that its publication was discontinued after the letter B. But my experience has taught me to consult all sources, because a heap of muck sometimes contains a grain of precious metal. (Consider also the dust heaps immortalized in Our Mutual Friend.) This is what I found in the short entry Bumper: “After Grimm [sic], a full glass which in toasting is knocked on the table or against another bumper. He compares [sic] with bomber-nickel.” (It is so easy to translate this text back into German!)

What is a bomber-nickel? And where did Grimm (I assume, Jacob Grimm) say it? His multivolume Deutsche Grammatik has a word index, compiled by Karl Gustav Andresen and published in 1865, but bumper is not in it. Once again I am turning to the assistance of our correspondents. Perhaps they will be able to find the relevant place in Jacob Grimm’s other books or Kleinere Schriften. I cannot imagine that Ebener made up the reference. The OED suggested cautiously that bumper is connected with bumping and its synonym thumping “very large.” Quite possibly, that’s all there is to it. Yet a link seems to be missing, namely some reference to drinking.

The short-lived adjective bumpsy (bumpsie) “drunk,” with an obscure suffix seemingly borrowed from tipsy, has often been cited by those who looked for the origin of bumper. I wonder whether bump up at one time also meant “guzzle” or that the noun bumper “drunkard” existed in colloquial use. Bumper “full glass” may, as suggested above, have been avoided by Samuel Johnson’s closest predecessors because it was current only as occasional slang, even though Johnson did not call the word low (an epithet of which he was fond). Bumper “full glass,” coexisting with bumper “drunkard,” is possible. For instance, a reader is someone who reads and a book for reading. Also, bump “drink heavily,” a homonym of bump “strike” and bump “bulge out, protrude,” may have had some currency as an expressive doublet of the little-known verb bum “consume alcohol.” Verbs ending in -mp (jump, thump, slump, dump, and of course bump) are invariably expressive. I wish it were possible to show that slum, a word of undiscovered origin, is in some way connected with slump!

The etymology of bumper is simple (not a “corruption” or a disguised compound), but, unfortunately, some details have been lost along the way. Let us not des-pair. Good wine needs no bush, so au bon père!

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Themas well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Themas well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A portrait of a man aiming a shotgun. Critical focus on tip of gun. Isolated on white. Photo by steele2123, iStockphoto.

The post Drinking vessels: ‘bumper’ appeared first on OUPblog.

By Dennis Baron

“It’s not surprising then that they get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them or anti-immigrant sentiment or anti-trade sentiment as a way to explain their frustrations.” –Barack Obama

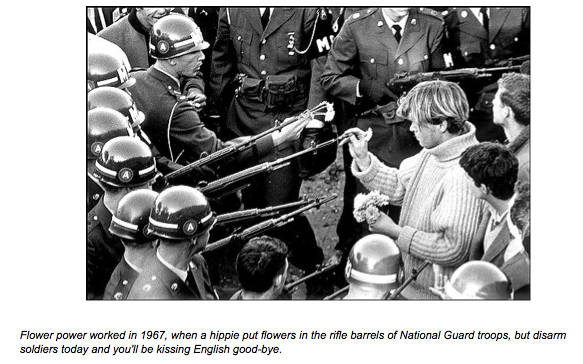

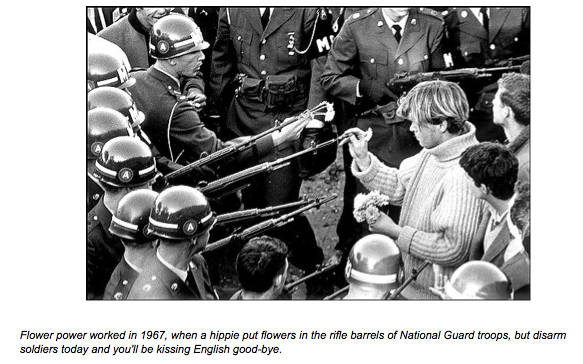

The bumper sticker on the back of a construction worker’s pickup truck caught my eye: “If you can read this, thank a teacher.”

This homage to education wasn’t what I expected from someone whose bitterness typically manifests itself in vehicle art celebrating guns and religion, but there was more: “If you can read this in English, thank a soldier.”

It was a “support our troops” bumper sticker that takes language and literacy out of the classroom and puts them squarely in the hands of the military.

It’s one thing to say that we owe our national security and the survival of the free world to military might. It’s something else again to be told that we need soldiers to protect the English language.

But according to this bumper sticker, any chink in our armor, any relaxation of our constant vigilance, any momentary lowering of the gun barrel, and we’ll all be speaking Russian, Iraqi, or even Mexican.

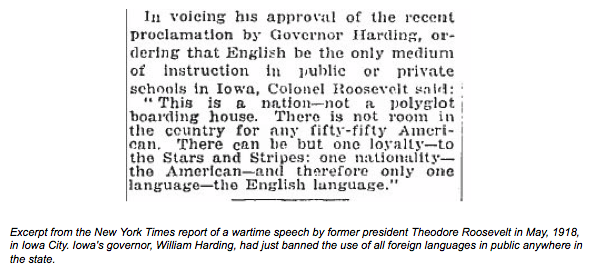

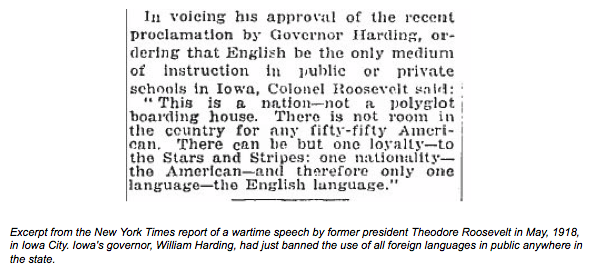

Supporters of official English argue that it’s the language of democracy — the language of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, not to mention the “Star-Spangled Banner,” “American Idol” and “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” (it doesn’t matter that Millionaire was a British show first, since Americans were British once themselves). English, goes the claim, is the “social glue” cementing the many cultures that underlie American culture. As Teddy Roosevelt said back in 1918, “This is a nation, not a polyglot boarding house.”

Supporters of official English argue that it’s the language of democracy — the language of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, not to mention the “Star-Spangled Banner,” “American Idol” and “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” (it doesn’t matter that Millionaire was a British show first, since Americans were British once themselves). English, goes the claim, is the “social glue” cementing the many cultures that underlie American culture. As Teddy Roosevelt said back in 1918, “This is a nation, not a polyglot boarding house.”

But apparently even the official language laws that states, cities, schools and businesses have put in place aren’t doing the job, so what we really need is to put a gun to people’s heads to make them use English.

Only that won’t work. The large number of translators killed in Iraq, or drummed out of the army for being gay, are two of the many indicators that our armies aren’t keeping the world safe for English.

The linguist Max Weinreich is credited with quipping that a language is a dialect with an army and a navy. But guns can’t literally keep a language safe at home any more than they can effectively seal a border to keep other languages out.

In a bold act of regime change and a glaring breach of homeland security, French streamed across the English borders in the 11th century along with the Norman armies, but French soldiers were unable to convert most of the Brits they encountered to the parlez-vous, at least not in the long term.

And while the Royal Navy helped spread English around the globe as part and parcel of the British Empire, what really undergirds English today as an international language isn’t military might, but the appeal of global capitalism, science, computer technology, t-shirts, and good old rock ‘n

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”