By Philip Carter

Published in 1937 The Hobbit was Tolkien’s first published work of fiction, though he had been writing on legends since at least 1915. His creation — a mythological race of ‘hobbits’, in which Bilbo Baggins takes the lead — had originally been intended for children. But from the outset Tolkien’s saga also proved popular with adults, perhaps appreciative of the hobbits’ curiously English blend of resourcefulness and respectability. The book was published by Stanley Unwin, following the recommendation of his 10-year old son, Rayner, who received a one shilling reader’s fee. Its success prompted Unwin to press for a sequel, and Tolkien now began work on The Lord of the Rings — a story that ‘grew in the telling’ at readings for the famous Inklings circle in Oxford.

[See post to listen to audio]

Or download the podcast directly.

Philip Carter is Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Read more about J.R.R. Tolkien on the Oxford DNB website. The Oxford DNB online is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,000 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 130 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The life of J.R.R. Tolkien appeared first on OUPblog.

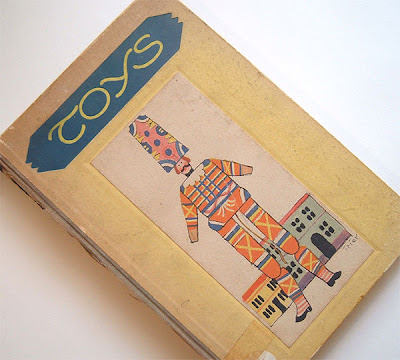

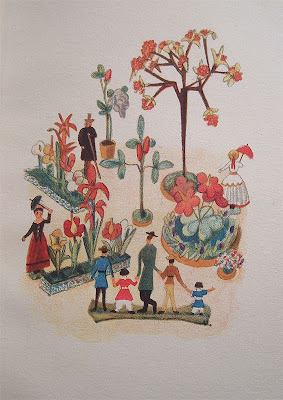

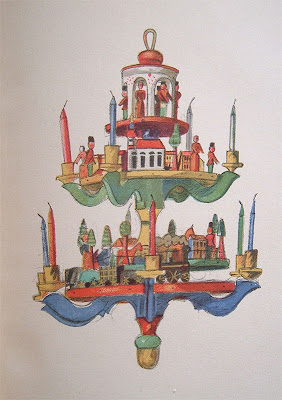

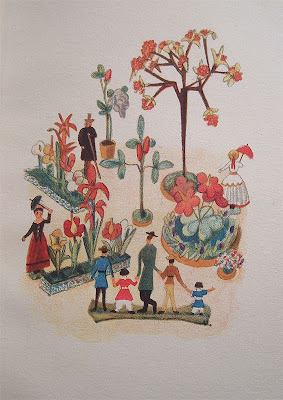

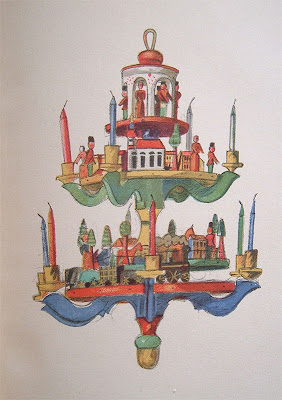

All excerpts from 'Toys', written by W.Trier, illustrated by O.Seyffert. First published in the original German, Berlin c.1920. First English translated edition quoted here, Unwin c.1930

A little girl will build a Garden of Eden out of some sand and pebbles and blades of grass. She puts some gaudy flowers in it and is happy in her play. Yes, she is much richer than we are. She creates a paradise out of trifles, a paradise which we can never succeed in creating with all our superior wisdom. And then her mother comes. She does not see the work of art, the paradise, but she thinks that perhaps the child may get dirty. She only sees sand, earth and pebbles. She drags her child aways and scolds her. But it is not from the 'dirt' alone she tears her, but from the Heaven her little soul was dwelling in.

Little Anne strokes and kisses her simple dolly a thousand times a day and loves it dearly. Her imagination dresses it today in a blue silk dress, and it is a princess. Tomorrow it is a poor suffering child that has to be tucked up in its warm cot. The day after tomorrow it is a proud rich prince - for there is no limit to imagination. And if the parents of this happy child give her a new doll with real curls, and which can open and close its eyes and really cry when it is clasped to her heart and wear an expensive dress...well, then the child no longer needs her imagination; the doll is quite perfect and there is nothing more to be made of it, no room left for imagination and form. Of course the time will come when Anne no longer values her first simple doll and yearns for the second one. But the longer she cannot have everything, the richer she remains.

A little boy is sitting on chairs turned topsy turvy and is puffing, panting and whistling. He is playing at trains. He himself is the engine. His coloured wooden toy figures are the passengers who get in and out. How much better off he is than his friend who has got a mechanical train which runs 'quite alone' round the room. Its owner cannot do much with it as his part of the game is done when he has wound it up. At last he examines the works, breaks them, and the expensive toy is a dead thing.

Christmas is the children's festival, and the day for toys. But our children are not only to have presents given to them. They must give presents they have made themselves. They must deck the Christmas tree with decorations they have made themselves; with coloured and golden stars. They will then feel the same joy that the dwellers in the Erz mountains feel, when each year they make anew the toys for the festival of festivals. Weeks before Christmas old and young are all busy making painted figures of the infant Jesus in the manger with the shepherds round it, also candlesticks in the shape of miners and the multi-coloured 'mountain spiders' as the wooden candelabra that are hung up at Christmas are called. And old and young are merry at their work.

It is this merriness we need so sorely. We town dwellers 'buy' our festival. what a difference!

Good morning. Over at my Live Journal blog, I'm hosting this week's Poetry Friday roundup. As regular readers here know, every Friday is Poetry Friday at

Writing and Ruminating.

Today, I'm feeling some John Keats; specifically, his Ode

"To Autumn", which features three stanzas of eleven lines each. All three have the same rhyme scheme for the first seven lines (ABABCDE), but stanza one (DCCE) ends a wee bit differently than two and three (CDDE). Such is the malleability of the Ode. What makes this poem special is not, however, the rhyme scheme; it is Keats's use of language and imagery, beginning with his decision to address the poem to Autumn itself, and to speak about it as a living, present thing.

This poem is lovely as is, but reading it aloud will give you further appreciation for the images and the sounds within it. I wish I could find Alan Rickman reading it, because his voice can turn me into a pile of mushy goo (don't believe me? Have a listen as he reads

Shakespeare's Sonnet 130. But I digress.) If you feel funny reading this aloud to yourself, then you can

listen to Nicholas Shaw read it for the BBC.

To Autumnby John Keats

I

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the mossed cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimmed their clammy cells.

II

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reaped furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twinèd flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

III

Where are the songs of Spring? Aye, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies. How much do I love some of his descriptions here? So very much that I'm thinking hyphenations should be used far more in everyday life. The evocativeness of "the mossed cottage-trees" alone is enough to stop me in my tracks. The entire second stanza is staggeringly gorgeous, speaking of the autumn hay. "[O]n a half-reaped furrow sound asleep,/Drowsed with the fume of poppies . . ." is better imagery and poetry than many can muster in the whole of their poems, and it's only part of one sentence here (and a fragment, at that).

Keats wrote the poem after spending some time out of doors on a fine autumn day. How do I know? Well, he wrote to a friend of his named Reynolds, and said so: "How beautiful the season is now—How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it. Really, without joking, chaste weather—Dian skies—I never lik'd stubble fields so much as now—Aye better than the chilly green of the spring. Somehow a stubble plain looks warm—in the same way that some pictures look warm—this struck me so much in my Sunday's walk that I composed upon it."

I believe that today, I'll take a walk and see what autumn has to offer.

I sha'n't be gone long.—You come too.*

And one more thing: Don't forget to check out the featured snowflakes for the Robert's Snow auction, which you can find listed at Seven Imp (or by clicking the pretty picture to your left - it's a button!)

And one more thing: Don't forget to check out the featured snowflakes for the Robert's Snow auction, which you can find listed at Seven Imp (or by clicking the pretty picture to your left - it's a button!) *Yes, that last italicized bit was Robert Frost, from one of my favorites of his poems,

"The Pasture". You can read the full text of that poem

in a prior post at my LiveJournal blog. Well-spotted, if you already knew that.

William Wordsworth was a linchpin in the development of modern poetry. Prior to Wordsworth, poets cast about to find a subject. With Wordsworth, in many ways, the subject was always himself. In fact, even during Wordsworth's life, Hazlitt observed that Wordsworth was "his own subject," which was, at the time, an original concept. Wordsworth's poems focused on emotion, ideas and sentiment as much as they did on the natural world, often with some interconnectedness. Even today, Wordsworth's poems tap into the subconcious (or even unconcious) minds of his readers and teach them how to feel, and how to connect with their true, spiritual self.

When I was in high school, one of the poems that had the greatest effect on me was William Wordsworth's Ode "Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood". Although the entire poem is fairly long -- eleven stanzas of varying length -- it is worth taking the time to read it in its entirety. First, to read its full content. Second, to bathe in the glorious language of the poem. If you have the time and inclination, I hope you'll follow the above link, and then come back to "talk" about the Ode with me.

The Ode leads off with an epigraph:

The Child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

&emsp Paulo majora canamus

The first three lines of the epigraph are the last three lines from another Wordsworth poem, "The Rainbow." The complete text of the poem is as follows:

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

& emsp Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.

The last line of the epigraph is a Latin quote from Virgil's Fourth Eclogue, and means "let us sing of greater things". Taken together, I believe that Wordsworth took his earlier nature poem about rejoicing in nature, and started thinking more carefully about the two ideas raised in the poem -- rejoicing in nature, and the idea that childhood influences later adulthood. Certainly those are topics explored in "Intimations of Immortality".

The Ode is essentially in three parts. Stanzas I through IV, which were written at least two years before the remainder of the poem, convey the poet's wistful sense that something has been lost. Stanzas V through VIII speak of resistence to the idea of growth or aging. Stanzas IX through XI reflect the acceptance of what remains, that there is still beauty in the world, and "strength in what remains behind": sympathy, empathy, faith and philosophy. Throughout the entire poem, the speaker's emotion is at odds with the joyous, bounteous world around him -- a departure from established traditions. At the same time, this poem can be read as a nature poem -- how children are very connected to nature and the world around them, but adults have dissociated themselves from the natural world, and can no longer feel their correct place in the natural world.

I want to focus in particular on three stanzas from the middle of the Ode, which are the ones that sang loudest to me when I first studied this poem in high school. I should note that these particular stanzas have been interpreted as believing in reincarnation, or at least in the pre-existence of the human soul. Wordsworth issued a denial that the Ode argues for preexistence of the soul, at the same time noting that there is nothing in Christian doctrine to preclude or contradict such a thing. They are stanzas V through VII:

V

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life's Star,

&emsp Hath had elsewhere its setting,

&emsp &emsp And cometh from afar:

&emsp Not in entire forgetfulness,

&emsp And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

&emsp From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison-house begin to close

&emsp Upon the growing Boy,

But he beholds the light, and whence it flows,

&emsp He sees it in his joy;

The Youth, who daily farther from the east

&emsp Must travel, still is Nature's Priest,

&emsp &emsp And by the vision splendid

&emsp &emsp Is on his way attended;

At length the Man perceives it die away,

And fade into the light of common day.

VI

Earth fills her lap with pleasures of her own;

Yearnings she hath in her own natural kind;

And, even with something of a Mother's mind,

&emsp And no unworthy aim,

&emsp The homely Nurse doth all she can

To make her Foster-child, her Inmate Man,

&emsp Forget the glories he hath known,

And that imperial palace whence he came.

VII

Behold the Child among his new-born blisses,

A six years' Darling of pigmy size!

See, where 'mid work of his own hand he lies,

Fretted by sallies of his mother's kisses,

With light upon him from his father's eyes!

See, at his feet, some little plan or chart,

Some fragment from his dream of human life,

Shaped by himself with newly-learnèd art;

&emsp A wedding or a festival,

&emsp A mourning or a funeral;

&emsp &emsp And this hath now his heart,

&emsp And unto this he frames his song:

&emsp &emsp Then will he fit his tongue

To dialogues of business, love, or strife;

&emsp But it will not be long

&emsp Ere this be thrown aside,

&emsp And with new joy and pride

The little Actor cons another part;

Filling from time to time his 'humorous stage'

With all the Persons, down to palsied Age,

That Life brings with her in her equipage;

&emsp As if his whole vocation

&emsp Were endless imitation.

I hope you enjoyed the reference to Shakespeare's As You Like It in the seventh stanza, to the little Actor playing parts on a humorous stage. It's a reference the soliloquy which begins "All the world's a stage", and discusses the roles played by a man throughout his life, from infancy to old age, a "second childishness."

I confess that even now, more than 25 years after I first learned this poem, I still love the idea of little souls streaming to earth, trailing clouds of glory, to be housed in new little people. And I thought of it often when my children were infants, looking into their newborn eyes and seeing in those eyes all the secrets of the universe, or so it seemed. But perhaps I was simply sleep-deprived; who can tell?

In this middle part of the Ode, Wordsworth traces the aging process, and how the soul gets shoved aside gradually by the daily concerns and obligations of life, causing man to lose connectedness with nature and the divine. At least, that's my reading of it. The middle four stanzas deal almost exclusively with the aging process and its effect on the soul. Stanza number 9, the longest stanza of the Ode by far, represents the "turn" in this work, where Wordsworth takes all the "facts" he's presented, and begins to make his "argument", that even with things fallen away, he can raise songs of thanks and praise knowing that somewhere in him is a soul that remains connected to the source from whence it came. Stanzas 10 and 11 return to nature and to appreciation for nature,

One more quote from the poem, the tenth stanza of which includes these lines:

What though the radiance which was once so bright

Be now for ever taken from my sight,

&emsp Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

&emsp We will grieve not, rather find

&emsp Strength in what remains behind;

&emsp In the primal sympathy

&emsp Which having been must ever be;

&emsp In the soothing thoughts that spring

&emsp Out of human suffering;

&emsp In the faith that looks through death,

In years that bring the philosophic mind.

Yes, movie-lovers, this portion of the poem is quoted in the movie, Splendor in the Grass, starring Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty. It is also, in many respects, the key point Wordsworth makes in the entire Ode.

According to many sources (including Harold Bloom), this poem is one of the most important poems in the English language. At the very least it was tremendously influential over a host of other poets, from Wordsworth's contemporaries like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats and George Gordon, Lord Byron to later poets, including W.B. Yeats, and including most American poets from Ralph Waldo Emerson through Walt Whitman and Wallace Stevens.

For today, and taking a line from Stanza 10 out of context,I hope that you will "Feel the gladness of the May!"

What a wonderful book, I would love to get my hands on a copy - in English! Wishing you and yours a very merry Christmas and a happy new year.

Carolyn

Willow House

I have never heard of this book...I will have to investigate this more.

Take care,

Alison x

I usesd to love making mud pies in the garden as a child. One minute they would be mud pies, the next delicious desserts !

Hello from a regular lurker. Thanking you for an inspiring read and wishing you all the best for The festive season. Merry Christmas!!

I so agree with the idea that the less we need to be happy, the richer we are. (I get so tired of my somewhat 'entitled' teenager who really believes she needs *things* to be happy. College is going to be eye-opening for her!)

How very true - seeing the masses of pinched and frowning faces round the shops this weekend, I think we could all benefit from reading this book.

Have a very Merry Christmas!

Merry Christams to you an your family!

I remember playing in the dirt imagining a garden.... thankgod my mum didn't tear me away from it :o)

Thank you for posting this. Happy Christmas to you!

Yes, yes and yes again and forever. We are each given the amazing gift of imagination at birth. How it is squandered, beaten out, and discouraged today. I thank the Powers that Be that I grew up in a time when the "temptations" of today did not exist.

I watch my three year old granddaughter and her amazing ability to spin the straw of imagination into the gold that should be every child's birthright. I dread the day when its glow slowly is extinguished.

Blessings and goodness, peace and joy be yours and your loved ones this season and throughout the New Year.

Merry Christmas to you from New York, and many thanks for your comments.

Hoping that all your talent has resulted in lots of success for you this season.

This blog is so very interesting. I love being introduced to new artists, books, anything creative that is sort on my wavelength.

I am sure that Santa will be good to you, and that in 2008 you will have great joy.

Best wishes.

This is a wonderful story - with great illustrations. Thank you for sharing it.

What a lovely post, thank you so much for those thoughtful words. By the way I saw you on Sarah's blog, your house sounds wonderful! Best Wishes at christmas x

Hey Gretel!!! Wishing you and Mr Gretel a very Happy Chrimbo and a supa-dupa New Year!!

Great post, Gretel! Thanks for sharing that. Merry Christmas and happy New Year to you and your family.

wonderful illustrations. Have a great christmas Gretel and best wishes for a very happy new year!

Merry Christmas to you two! (It's early yet for you, but Santa should have been by already). Thinking of you today.

What lovely illustrations! Merry Christmas!

Thanks for sharing this! I always remember my animation teacher saying that the less you fill in every detail, the more you leave open in your drawing, the more it invites the audience into your work and allows them to participate by "connecting the dots" or filling in the missing bits with their own imagination.