new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: fantasy writing, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: fantasy writing in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

keilinh,

on 8/8/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Awards,

science fiction,

writing tips,

young adult,

writing,

fantasy,

plotlines,

fantasy writing,

Writer Resources,

Publishing 101,

writing 101,

Tu Books,

writing award,

New Visions Award,

New Voices/New Visions Award,

sci-fi writing,

Add a tag

In this series, Tu Books Publisher Stacy Whitman shares advice for aspiring authors, especially those considering submitting to our New Visions Award.

Last week on the blog, I talked about hooking the reader early and ways to write so you have that “zing” that captivates from the very beginning. This week, I wanted to go into more detail about the story and plot itself. When teaching at writing conferences, my first question to the audience is this:

What is the most important thing about a multicultural book?

I let the audience respond for a little while, and many people have really good answers: getting the culture right, authenticity, understanding the character… these are all important things in diverse books.

But I think that the most important part of a diverse novel is the same thing that’s the most important thing about any novel: a good story. All of the other components of getting diversity right won’t matter if you don’t have a good story! And getting those details wrong affects how good the story is for me and for many readers.

So as we continue our series discussing things to keep in mind as you polish your New Visions Award manuscripts, let’s move the discussion on to how to write a good story, beyond just following the directions and getting a good hook in your first few pages. This week, we’ll focus on refining plot.

Here are a few of the kinds of comments readers might make if your plot isn’t quite there yet:

- Part of story came out of nowhere (couldn’t see connection)

- Too confusing

- Confusing backstory

- Plot not set up well enough in first 3 chapters

- Bizarre plot

- Confusing plot—jumped around too much

- underdeveloped plot

- Too complicated

- Excessive detail/hard to keep track

- Too hard to follow, not sure what world characters are in

We’ll look at pacing issues too, as they’re often related:

- Chapters way too long

- Pacing too slow (so slow hard to see where story is going)

- Nothing gripped me

- Too predictable

Getting your plot and pacing right is a complicated matter. Just being able to see whether something is dragging too long or getting too convoluted can be hard when you’re talking about anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand words, all in one long file. Entire books have been written on how to plot a good science fiction and fantasy book. More books have been written on how to plot a good mystery. If you need more in-depth work on this topic, refer to them (see the list at the end of this post).

Getting your plot and pacing right is a complicated matter. Just being able to see whether something is dragging too long or getting too convoluted can be hard when you’re talking about anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand words, all in one long file. Entire books have been written on how to plot a good science fiction and fantasy book. More books have been written on how to plot a good mystery. If you need more in-depth work on this topic, refer to them (see the list at the end of this post).

So we won’t get too in depth here, but let’s cover a few points.

Know your target audience

When you’re writing for children, especially young children (middle grade, chapter books, and below), your plot should be much more linear than a plot for older readers who can hold several threads in their heads at once.

Teens are developmentally ready for more complications—many of them move up to adult novels during this age, after all—but YA as a category is generally simpler on plot structure than adult novels in the same genre. This is not to say the books are simple-minded. Just not as convoluted… usually. (This varies with the book—and how well the author can pull it off. Can you?)

But the difference between middle grade and YA is there for a reason—kids who are 7 or 8 or 9 years old and newly independent readers need plots that challenge them but don’t confuse them. And even adults get confused if so much is going on at once that we can’t keep things straight. Remember what we talked about last time regarding backstory—sometimes we don’t need to know everything all at once. What is the core of your story?

Linear plot

Note that “too complicated” is one of the main complaints of plot-related comments readers had while reading submissions to the last New Visions Award.

Don’t say, “But Writer Smith wrote The Curly-Eared Bunny’s Revenge for middle graders and it had TEN plot threads going at once!” Writer Smith may have done it successfully, but in general, there shouldn’t be more than one main plot and a small handful of subplots happening in a stand-alone novel for middle-grade readers.

If you intend your book to be the first in a series of seven or ten or a hundred books, you might have seeds in mind you’d like to plant for book seventy-two. Unless you’re contracted to write a hundred books, though, the phrase here to remember is stand-alone with series potential. Even Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was pretty straightforward in its plotting—hinting at backstory, but not dumping backstory on readers in book one; setting the stage for potential conflicts down the road but not introducing them beforetime. Book 1 of Harry Potter really could have just stood on its own and never gone on to book 2. It wouldn’t have been nearly as satisfying as having the full 7-book arc, but note how seamlessly details were woven in, not calling attention to themselves even though they’re setting the stage for something later. Everything serves the linear plot of the main arc of book 1’s story. We only realize later that those details were doing double duty.

Thus, when you’re writing for children and young adults, remember that a linear main plot is your priority, and that anything in the story that is not serving the main plot is up on the chopping block, only to be saved if it proves its service to the main plot is true. Plotting affects pace

Plotting affects pace

In genre fiction for young readers, pacing is always an issue. Pacing can get bogged down by too many subplots—the reader gets annoyed or bored when it takes forever to get back to the main thrust of the story when you’re wandering in the byways of the world you created.

Fantasy readers love worldbuilding (to be covered in another post), but when writing for young readers, make sure that worldbuilding serves as much to move the plot forward as to simply show off some cool worldbuilding. Keep it moving along.

Character affects plot

This was not a complaint from the last New Visions Award, but another thing to keep in mind when plotting is that as your rising action brings your character into new complications, the character’s personality will affect his or her choices—which will affect which direction the plot moves. We’ll discuss characterization more another day, but just keep in mind that the plot is dependent upon the choices of your characters and the people around them (whether antagonists or otherwise). Even in a plot that revolves around a force of nature (tornado stories, for example), who the character is (or is becoming) will determine whether the plot goes in one direction or another.

Find an organizational method that works for you

This is not a craft recommendation so much as a tool. Plotting a novel can get overwhelming. You need a method of keeping track of who is going where when, and why. There are multiple methods for doing this.

Scrivener doesn’t work for all writers, so it might not be your thing, but I recommend trying out its corkboard feature, which allows you to connect summaries of plot points on a virtual corkboard to chapters in your book. If you need to move a plot point, the chapter travels along for the ride.

An old-fashioned corkboard where you can note plot points and move them around might be just as easy as entering them in Scrivener, if you like the more tactile approach.

Another handy tool is Cheryl Klein’s Plot Checklist, which has a similar purpose: it makes the writer think about the reason each plot point is in the story, and whether those points serve the greater story.

Whether you use a physical corkboard, a white board, Scrivener, or a form of outlining, getting the plot points into a form where you can see everything happening at once can help you to see where things are getting gummed up.

Further resources

This post is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to plotting a book. Here are some books and essays that will be of use to the writer seeking to fix his or her plot problems. (Note that some of these resources will be more useful to some writers than others, and vice versa. Find what works for you.)

- “Muddles, Morals, and Making It Through: Or Plots and Popularity,” by Cheryl Klein in her book of essays on writing and revising, Second Sight.

- In the same book by Cheryl Klein, “Quartet: Plot” and her plot checklist.

- The Plot Whisperer by Martha Alderson

- I haven’t had experience with this resource, but writer friends suggest the 7-point plot ideas of Larry Brooks, which is covered both in a blog series and in his books

And remember!

Further Reading:

New Visions Award: What NOT to Do

Ask an Editor: Hooking the Reader Early

The New Visions Guidelines

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers.

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers.

Filed under:

Awards,

New Voices/New Visions Award,

Publishing 101,

Tu Books,

Writer Resources Tagged:

fantasy,

fantasy writing,

New Visions Award,

plotlines,

sci-fi writing,

science fiction,

writing,

writing 101,

writing award,

writing tips,

young adult

By:

rgarcia406,

on 6/26/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

science fiction,

writing tips,

writing advice,

writing resources,

Science Fiction/Fantasy,

worldbuilding,

fantasy writing,

Writer Resources,

young adult writing,

Publishing 101,

stacy whitman,

Tu Books,

Add a tag

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers. Parts of this blog post were originally posted at her blog, Stacy Whitman’s Grimoire.

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers. Parts of this blog post were originally posted at her blog, Stacy Whitman’s Grimoire.

Last week, I discussed why worldbuilding in speculative fiction can be so challenging for authors. How do we introduce a completely new world without infodumping or confusing readers? I gave some examples of worldbuilding done well in popular YA science fiction and fantasy: The Hunger Games, Divergent, and Twilight. In all these cases, the starting point is in some way relatable, or there is something about the character (Tris, Katniss) that hooks the reader. First pages should be character- and plot-driven, and worldbuilding should support rather than dominate. That gives these books an easy entry point and wide appeal.

There are three primary approaches to worldbuilding:

Reader learns world alongside character

Readers of Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, and Twilight figure out the world alongside the main character. Information is spooled out as the character learns it, so the reader doesn’t have to absorb everything at once. This is a low bar for entry, not requiring much synthesis of information. The character is almost a stand-in for the reader.

Exposition: questions raised, then answered

What about Hunger Games? Now it gets a little tougher. Suzanne Collins starts out with a perfectly relatable (if a tiny bit cliche) situation, the main character waking up and seeing her family. We get some exposition on Katniss’s family and the cat who hates her.

But it becomes non-cliche by page 2, when we learn about the Reaping. Ah! What’s the Reaping, you ask? We don’t know yet. Now the bar for entry is raised. There is a question, the answer for which you’re going to have to read further to find out. The infodumpage level is low, but there is still some exposition in the next few pages, letting us know that Katniss lives in a place called District 12, nicknamed the Seam, and that her town is enclosed by a fence that is sometimes electrified—and which is supposed to be electrified all the time.

Collins’s approach to spooling out a little information at a time is to explain each new term as she goes, but some readers think that feels unnatural in a first person voice because the narrator would already know these things, so why is she explaining them to the reader?

It depends on the story, in my opinion—Collins makes it work because of how she crafted Katniss’s voice. It is a very fine line to walk—I can’t tell you how many submissions I’ve received that start out with, “My name is X. I am Y years old. I live in a world that does Z,” an obvious example of how this approach becomes downright clumsy when not handled with Collins-esque finesse.

“Incluing”: questions raised, then reader infers answers bit by bit

Then there is the opposite end of the spectrum, in which the reader is given clues to work out rather than having any new terms explained to them. This approach needs just as much, if not more, finesse. It’s a process that some readers who are new to speculative fiction might stumble over the most, which is why I think there’s so little of it in middle grade and YA fantasy and science fiction. I’ve seen it called “incluing,” which is a silly word, but I don’t know of another name for it and the description of incluing in that Wikipedia link is exactly the kind of worldbuilding I—as a lifelong fantasy fan—prefer to see in the beginning of a book, particularly one set in a world that has no connection to our own, or if it’s in the future of our world far enough into the future that the society is unrecognizable to us, such as the society in Tankborn. Karen Sandler does a wonderful job at incluing readers as we read chapter 1 of the first book in the Tankborn trilogy.

The prominent example I like to give writers for this kind of worldbuilding is from The Golden Compass. Check out the first paragraph of that book:

“Lyra and her daemon moved through the darkening hall, taking care to keep to one side, out of sight of the kitchen. The three great tables that ran the length of the hall were laid already, the silver and the glass catching what little light there was, and the long benches were pulled out ready for the guests. Portraits of former Masters hung high up in the gloom along the walls. Lyra reached the dais and looked back at the open kitchen door, and, seeing no one, stepped up beside the high table.”

Pullman jumps right into the scene, with Lyra sneaking down the dining hall with her daemon. We’re hooked—she’s doing something sneaky, and we don’t know what. And we want to know. We don’t even know what the daemon physically looks like until paragraph 4, and even then we don’t know why he’s called a daemon or what makes a daemon special.

What is a daemon, anyway? We don’t know! In fact, this is one of the major conflicts of the book—we need to read more to find out about daemons, and further mysteries are revealed as we read that deepen our understanding of daemons and of Lyra’s world in general. As we discover more clues that intrigue us, we want to know more, and keep reading.

But the line between intriguing the reader and confusing the reader is very thin, and I would argue that for some readers it’s in a different place than for others. Those of us who are familiar with fantasy might be more willing to patiently wait for more information about daemons because we trust that this author will let us know what we need to know when the time is right. We know that they’re teasing us with this information so as not to overburden us within the first few pages of the book (or, in the case of The Golden Compass, because the reader can’t know what the majority of people in that world don’t know, either).

In situations in which you need to establish a world that’s entirely different from our own, I find that putting a character in a situation that’s somewhat familiar to the reader can help with establishing the unfamiliar. In Karen Sandler’s Tankborn, for example, Kayla has to watch her little brother instead of going to a street fair with her friends. While Kayla calls him her “nurture brother” instead of just her brother, it’s still a situation to which a lot of readers can relate, even if it is set on another planet and her brother is catching nasty arachnid-based sewer toads instead of familiar Earth frogs and toads.

In situations in which you need to establish a world that’s entirely different from our own, I find that putting a character in a situation that’s somewhat familiar to the reader can help with establishing the unfamiliar. In Karen Sandler’s Tankborn, for example, Kayla has to watch her little brother instead of going to a street fair with her friends. While Kayla calls him her “nurture brother” instead of just her brother, it’s still a situation to which a lot of readers can relate, even if it is set on another planet and her brother is catching nasty arachnid-based sewer toads instead of familiar Earth frogs and toads.

M. K. Hutchins, author of Drift, approached it in a completely different way. She starts with a dangerous situation—a family on the run from authorities, splitting up. The mother, our main character Tenjat, and his sister Eflet are embarking on a terrible journey that’s almost certain death, setting off on a raft in the middle of the night into an ocean full of snake-like monsters, and leaving the family’s father and smallest brother behind to face unknown punishment. While perhaps no reader has been chased by authorities in the middle of the night, it is a dangerous situation and a parting of family—mixing the familiar (family) with the unfamiliar (a dangerous situation in a completely new setting).

It’s the difference between showing and telling. Philip Pullman, Karen Sandler, and M. K. Hutchins all show us how their worlds works, rather than pausing to tell us how it works (“in this world, all people are born with an animal companion called a daemon”).

Telling can work, though, especially in small doses—Katniss’s voice is so conversational that the brief moments of telling in the first few pages of The Hunger Games work, particularly because Collins is mostly showing what Katniss is up to. The brief pauses to “infodump” feel like the reader is being told a story by a storyteller, like a friend telling a story over the kitchen table after a nice big meal would pause and explain something you didn’t understand (a friend who’s a very good storyteller). It’s an awareness of audience that most speculative fiction doesn’t have the luxury of.

Showing isn’t always better, and telling isn’t always bad, when done right and mixed in with showing. Whichever method you use, remember that sometimes readers will trip over new words so you need to give them as much context as possible without over-infodumping.

And here is where the art comes in. I can’t tell you what that balance is, but if you look at examples like the ones above, you’ll get a better feel for how much to reveal and how much to hold back in your first few pages—revealing enough to orient your reader and give them a sense of the differences of this world (while grounding them in something familiar like Lyra’s hallway or Katniss’s humble home) while seeking to avoid overburdening them with too much all at once.

What about you? How have you found the right balance of introducing your world without overburdening the reader? What books do you recommend that do this particularly well?

Filed under:

Publishing 101,

Tu Books,

Writer Resources Tagged:

fantasy writing,

science fiction,

Science Fiction/Fantasy,

stacy whitman,

Tu Books,

worldbuilding,

writing advice,

writing resources,

writing tips,

young adult writing

By:

Hannah,

on 6/19/2014

Blog:

The Open Book

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

science fiction,

writing tips,

writing advice,

writing resources,

Science Fiction/Fantasy,

worldbuilding,

fantasy writing,

Writer Resources,

young adult writing,

Publishing 101,

stacy whitman,

Add a tag

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers. Parts of this blog post were originally posted at her blog, Stacy Whitman’s Grimoire.

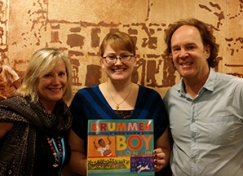

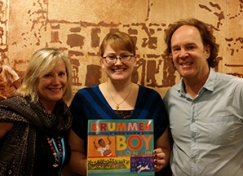

During the first week of June, I attended the Asian Festival of Children’s Content in Singapore. At the conference, I met writers from all over Asia and the Pacific, discussing craft, marketing their books at home and abroad, and translation. I even ran into Mark Greenwood and Frané Lessac, the Australian author/illustrator team behind the LEE & LOW picture book The Drummer Boy of John John. I enjoyed all the panels and the chance to see Singapore and meet so many people from the other side of the world—it gives you a perspective as an editor you might not otherwise have.

One of the panels I participated in was a First Pages event, in which I read about 20 first pages of picture books, middle grade, and YA novels and then gave feedback on whether the pages were working for me and if I’d want to read more.

Stacy Whitman with author Mark Greenwood and illustrator Frané Lessac

For the fantasy and science fiction entries, a common problem was—and is in any new writer’s writing—revealing enough about the world that you create interest and intrigue, but not too much. Too much, and you risk alienating your audience, confusing them, or simply not hooking them. Reader reactions are so subjective. One person might think there’s not nearly enough worldbuilding in a book (“give me more! MORE!”) and another might say of the exact same book that what worldbuilding there is was way too confusing (“I couldn’t keep all those made-up words straight!”).

So how do you, as the author, balance the needs of such a wide range of readers when you’re working in a complex world? And how do you balance the need to establish your characters, setting, and plot with the need to spool out information to your reader to intrigue them rather than confuse them?

This is a question that almost every author and editor of speculative fiction struggles with, particularly because we, as veterans of the genre, are already more comfortable with a lot of jargon than your average teen reader, particularly teen readers whose preference for fantasy runs more toward the contemporary paranormal variety.

Stacy Whitman at the famous Singapore merlion fountain

There are a number of reasons why I think Twilight was so popular on such a broad scale, but one of the biggest ones was the relatability of the initial situation. Not vampires showing up at school—before that. We start with a simple story about a girl who is leaving her mother behind in Arizona to live with her father in an unknown small town on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington. Relatable: divorced parents, fish out of water, adapting to a new school and a new climate.

Think about all the really big fantasy hits of the last decade or so in children’s and YA fiction: Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, Twilight, Hunger Games, Divergent. Of these books’ beginnings, only the dystopian tales start all that far outside the everyday experiences of your average young reader, and even The Hunger Games starts with a relatable situation—a coal mining family lives in a desperate situation and must hunt for food.

While most kids who would have access to The Hunger Games don’t live under a despotic regime, it’s plausible that it could happen in the real world. Every kid has been hungry at some point, though perhaps not as hungry and desperate as Katniss. Every kid has taken a test in school, and sometimes it feels like those standardized tests do determine your everlasting fate, as they do in Divergent, even if Tris’s Abnegation explanations are a little tedious. Harry Potter and Percy Jackson are ordinary kids going to school, living somewhat normal lives (even if abusive ones, in the case of Harry) before their worlds change with the discovery of magic.

Stacy Whitman speaking on a panel at the Asian Festival of Children’s Content.

There are three primary approaches to worldbuilding:

Reader learns world alongside character

Exposition: questions raised, then answered

“Incluing”: questions raised, then reader infers answers bit by bit

Next Thursday, I’ll go into detail about each of these techniques and give some examples. In the meantime, think about your favorite science fiction and fantasy books. How do they bring you into their world? What works best for you as a reader? Answering these questions about your own reading preferences can help guide you as a writer.

Filed under:

Publishing 101,

Writer Resources Tagged:

fantasy writing,

science fiction,

Science Fiction/Fantasy,

stacy whitman,

worldbuilding,

writing advice,

writing resources,

writing tips,

young adult writing

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers. This blog post was originally posted at her blog, Stacy Whitman’s Grimoire.

I have to admit, I really hate reading villain POVs. There are so few villains that have any redeemable qualities, and especially starting a book out with the villain’s point of view when they’re murdering and/or plundering just makes me go, “Why do I want to read this book, again?”

This is actually one of the things I hated most about the famous adult fantasy series Wheel of Time, though I love the series in general: I hated the amount of time spent on this Forsaken’s love of naked mindless servants, and that Forsaken’s love of skinning people, or whatever. Yeah, yeah, I get it, they’re irredeemably evil. Get back to someone I’m actually ROOTING FOR, which is why I’m reading the book!

Vodnik, the villain from Bryce Moore’s novel Vodnik

Sometimes it’s important to briefly show the villain’s point of view to convey to the reader some information that our hero doesn’t have, but I find more and more that my tolerance for even these kinds of scenes is thinning fast. Too often it’s a substitute for more subtle forms of suspense, laying clues that the reader could pick up if they were astute, the kind of clues that the main character should be putting together one by one to the point where when he or she finally figures it out. Then the reader slaps their own forehead and says, “I should have seen that coming!”

It’s a completely different matter, of course, when the whole point is for the “villain” to simply be someone on another side of an ideological or political divide where there are no true “bad guys.” Usually this happens in a book in which your narrators are unreliable, which can be very interesting. Often the villain is the hero in their own story, which is far more interesting than a “pure evil” villain—in Lord of the Rings, Sauron is much less interesting than Saruman. Sauron is the source of pure evil, but Saruman made a choice—he thinks, well, evil will win anyway, I might as well be on top in the new world order. There are complications to his motivations.

Tu Books author Bryce Moore (Vodnik) recently reviewed the first Captain America movie and had this to say about how a character becomes evil, which I think is apropos to this discussion:

Honestly, if writers spent as much time developing the origin and conflicted ethos of the villains of these movies, I think they’d all be doing us a favor. As it is, it’s like they have a bunch of slips of paper with different elements on them, then they draw them at random from a hat and run with it. Ambitious scientist. Misunderstood childhood. Picked on in school.

That’s not how evil works, folks. You don’t become evil because you get hit in the head and go crazy. You become evil by making decisions that seemed good at the time. Justified. Just like you become a hero by doing the same thing. A hero or a villain aren’t born. They’re made. That’s one of the things I really liked about Captain America. He’s heroic, no matter how buff or weak he is.

This is, perhaps, the best description of why villain POVs bug me so much: because they’re oversimplified, villainized. And for some stories, I think villainization works, but I don’t want to see that point of view, because it’s oversimplified and uninteresting. When it’s actually complicated and interesting, then it becomes less “the villain” and more nuanced—sometimes resulting in real evil (after all, I doubt Hitler was an evil baby; he made choices to become the monster he became) and sometimes resulting in a Democrat instead of a Republican or vice versa—ideological, political differences between (usually) relatively good people.

But there’s a line for me, generally the pillaging/raping/murdering/all manner of human rights abuses line, at which I’m sorry, I just don’t care about this guy’s point of view. The equivalent of this in middle grade books—where pillages/murders/rapes are (hopefully) fewer—or young adult books is the pure evil villain who’s just out to get the main character because the villain is black-hearted, mean, vile, what-have-you. Evil through and through, with no threads of humanity. (Though honestly if he’s killing people “for their own good” to protect a certain more nuanced human viewpoint, I generally still don’t want to see that from his POV.)

What’s the line for you? Do you like villain points of view? Do you feel they add depth to a story? At what point do you think a villain POV goes from adding nuance or advancing the plot to annoying?

Filed under:

Publishing 101,

Tu Books Tagged:

ask an editor,

fantasy writing,

Notes from the Editors,

writing advice,

writing resources,

writing tips

Ask anyone. The biggest question when you're a writer is likely "how do you get published?" Some writers start thinking about it way before they should—before they've focused their attention on improving their craft and writing a good story. In my opinion that should always come first and if you're serious about getting published, well, then that's your first step, isn't it? Make sure your writing is good and write something worth reading.

That said, when you are ready to get published, what do you do? There's plenty of advice on how to get published out there—volumes and volumes written on the subject. But within all that wealth of information that's available, how do you know which advice is right for you, especially if you write within a specific genre like fantasy (or an even more specialized niche like fantasy YA or say paranormal YA romance)? The key (aside from having a really great manuscript) is in being detail oriented and communicating well. Sounds easy enough, but if you've been writing for any length of time at all, then you know it can be tricky. Here are a few tips that I hope will help you in your search for publication.

Continue reading →

Getting your plot and pacing right is a complicated matter. Just being able to see whether something is dragging too long or getting too convoluted can be hard when you’re talking about anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand words, all in one long file. Entire books have been written on how to plot a good science fiction and fantasy book. More books have been written on how to plot a good mystery. If you need more in-depth work on this topic, refer to them (see the list at the end of this post).

Getting your plot and pacing right is a complicated matter. Just being able to see whether something is dragging too long or getting too convoluted can be hard when you’re talking about anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand words, all in one long file. Entire books have been written on how to plot a good science fiction and fantasy book. More books have been written on how to plot a good mystery. If you need more in-depth work on this topic, refer to them (see the list at the end of this post). Plotting affects pace

Plotting affects pace Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers.

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers.

Terrific tips – plot is so, so important, but I have seen too many otherwise good writers leave the basics behind when they’re aiming for diversity. It’s obvious that both are important, and I think you’ve nailed a lot of the details here. Thanks!