new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Quotes &, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 35

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Quotes & in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

“The Catholic Church was derived from three sources. Its sacred history was Jewish, its theology was Greek, its government and canon law were, at least indirectly, Roman… In Catholic doctrine, divine revelation did not end with the scriptures, but continued from age to age through the medium of the Church, to which, therefore, it was the duty of the individual to submit his private opinions. Protestants, on the contrary, rejected the Church as a vehicle of revelation; truth was to be sought only in the Bible, which each man could interpret for himself. If men differed in their interpretation, there was no divinely appointed authority to decide the dispute. In practice, the State claimed the right that had formerly belonged to the Church, but this was a usurpation. In Protestant theory, there should be no earthly intermediary between the soul and God.

The effects of this change were momentous. Truth was no longer to be ascertained by consulting authority, but by inward meditation. There was a tendency, quickly developed, toward anarchism in politics, and, in religion, toward mysticism, which had always fitted with difficulty into the framework of Catholic orthodoxy. There came to be not one Protestantism, but a multitude of sects; not one philosophy opposed to scholasticism, but as many as there were philosophers; not, as in the thirteenth century, one Emperor opposed to the Pope, but a large number of heretical kings. The result, as thought in literature, was a continually deepening subjectivism, operating at first as a wholesome liberation from spiritual slavery, but advancing steadily toward a personal isolation inimical to social sanity.

Modern philosophy begins with Descartes, whose fundamental certainty is the existence of himself and his thoughts, from which the external world is to be inferred. This was only the first stage in a development, through Berkeley and Kant, to Fichte, for whom everything is only an emanation of the ego. This was insanity, and, from this extreme, philosophy has been attempting, ever since, to escape into the world of everyday common sense.”

– Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy

“Lost things have their own special category. So long as they’re lost, and felt to be lost, they belong to the imagination and live more vividly than before. They make a mystery.” — Sven Birkerts, The Other Walk.

“Lost things have their own special category. So long as they’re lost, and felt to be lost, they belong to the imagination and live more vividly than before. They make a mystery.” — Sven Birkerts, The Other Walk.

Birkerts’ best personal essays are steeped in an anxious nostalgia that is, in intensity if not in focus, all too familiar to me.

“The Pump You Pump the Water From,” on his wistfulness for the writing processes of his younger days, is online at the Los Angeles Review of Books. If you like it, pick up The Other Walk, and read that, too.

“For the young — and especially the young writer — memory and imagination are quite distinct, and of different categories. In a typical first novel, there will be moments of unmediated memory (typically, that unforgettable sexual embarrassment), moments where the imagination has worked to transfigure a memory (perhaps that chapter in which the protagonist learns some lesson about life, whereas in the original the novelist-to-be failed to learn anything), and moments when, to the writer’s astonishment, the imagination catches a sudden upcurrent and the weightless, wonderful soaring that is the basis for the fiction delightingly happens.

These different kinds of truthfulness will be fully apparent to the young writer, and their joining together a matter of anxiety. For the older writer, memory and the imagination begin to seem less and less distinguishable. This is not because the imagined world is really much closer to the writer’s world than he or she cares to admit (a common error among those who anatomize fiction) but for exactly the opposite reason: that memory itself comes to seem much closer to an act of imagination than ever before. My brother distrusts most memories. I do not mistrust them, rather I trust them as workings of the imagination, as containing imaginative as opposed to naturalistic truth.”

– Julian Barnes, Nothing to Be Frightened Of

Previously:

On the melding of fact and invention in fiction

On the melding of fact and invention in fiction II

Welty v. Maxwell on autobiography in fiction

On creating the feeling you want the reader to feel

Fiction and autobiography edition, featuring Somerset Maugham, Alexander Chee, Joan Didion, Jean Rhys, and Graham Greene, and semi-estranged half-sisters AS Byatt and Margaret Drabble

“Fact and fiction are so intermingled in my work that, looking back, I can hardly distinguish one from the other.” — Somerset Maugham (in video above)

“I sat down to write a conventionally autobiographical novel. I wrote 135 pages, sent it to my agent at the time and she said, You know, the writing is beautiful, but probably no one is going to believe this much bad stuff happens to one person… I went to Aristotle’s Poetics, for his rules for the structuring of tragedies, and proceeded to alter my book from there, erasing the way it resembled my life and making something more and more fictional as time went on. So it’s as if I erased the core of my life and left the details to help convince, inserting an impostor who resembles me into the scene.” — Alexander Chee, on writing Edinburgh

“There was a certain tendency to read Play It As It Lays as an autobiographical novel, I suppose because I lived out here and looked skinny in photographs and nobody knew anything else about me. Actually, the only thing Maria and I have in common is an occasional inflection, which I picked up from her — not vice versa — when I was writing the book. I like Maria a lot. Maria was very strong, very tough.” — Joan Didion

“When I think about it, if I had to choose, I’d rather be happy than write. You see, there’s very little invention in my books. What came first with most of them was the wish to get rid of this awful sadness that weighed me down. I found when I was a child that if I could put the hurt into words, it would go. It leaves a sort of melancholy behind and then it goes. I think it was Somerset Maugham who said that if you ‘write out’ a thing… it doesn’t trouble you so much. You may be left with a vague melancholy, but at least it’s not misery — I suppose it’s like a Catholic going to confession, or like psychoanalysis.” — Jean Rhys

“A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead.” — Graham Greene, The End of the Affair (his most autobiographical novel)

“I know at least one suicide and one attempted suicide caused by people having been put into novels. I know writers to whom I don’t tell personal things – which is hard, as these writers are always the most interested in what one has to tell. All writing is an exercise of power and special pleading – telling something your own way, in a version that satisfies you. Others must see it differently. As I get older I increasingly understand that the liveliest characters – made up with the most freedom – are combinations of many, many people, real and fictive, alive and dead, known and unknown. I really don’t like the idea of ‘basing’ a character on someone, and these days I don’t like the idea of going into the mind of the real unknown dead. I am also afraid of the increasing appearance of ‘faction’ — mixtures of biography and fiction, journalism and invention. It feels like the appropriation of others’ lives and privacy.” — AS Byatt

“Interviewer: ‘Can you describe the process of transforming material into fiction?’ Drabble: ‘Not sticking too closely to the accidental and circu

“Do you think writers have to feel what they want the reader to feel when they’re writing?” I asked my friend Alex Chee in email this weekend, after reading a new story of his that powerfully evokes the kind of moony, depressive, sickeningly self-reflective state I’ve been in. “Because the end of this novel is completely kicking my ass. I hate what I’m learning about myself as I write it, but the dissociated part of me is fascinated that I’m learning so much about myself by writing something that is not literally about me at all.”

He replied:

I think we do. In true first person, definitely. God knows it was why writing Edinburgh was hell. When someone asked me if I wanted to work on a screenplay for it I thought ‘Not for anything in the world.’ But also, for writers, there’s a book that makes you as you make it. And in the writing of it, you learn to master both yourself and the book in a way you never have to again.

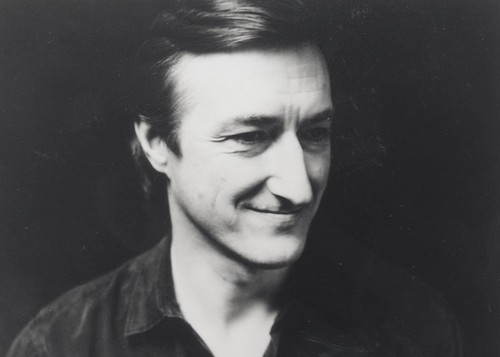

What comes to mind is advice Annie Dillard gave us, to think of yourself as going down in an old-fashioned diving bell [see above], a thread of air connecting you back to yourself. And when you must, to return to the surface. To treat an engagement with that work like deep sea diving. She meant for essays, memoir, but I found it applies to first person autobiographical fiction, too.

I guess one reason Alex and I are so fascinated by Jean Rhys is that she struggled with the same problems. But see Toni Morrison’s stern warning about writing from anything but the cold, cold brain.

Debate and discussion — but not attacks — are welcome in the comments below.

By: Maud Newton,

on 10/6/2010

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mark twain,

Ruminations on Writing,

Quotes & Excerpts,

eb white,

muriel spark,

tgbiw,

whingeing about novel writing,

absurdities of human existence,

one man's meat,

peter de vries,

Add a tag

Some writers shame and immobilize me with their brilliance, while others, like Twain, de Vries and Spark, dwarf my own efforts but inspire me to keep on.

Some writers shame and immobilize me with their brilliance, while others, like Twain, de Vries and Spark, dwarf my own efforts but inspire me to keep on.

It’s hard to pinpoint what separates the two groups; if pressed I’d say it’s an affinity of perspective — a morbid fixation on the absurdities of human existence — combined with precision, bluntness, and humor.

Of late, E.B. White has joined the second group. I’ve been making my way through One Man’s Meat — a collection of essays about leaving New York City for his Maine farm — and I particularly enjoyed this bit from an essay on his failed efforts to raise turkeys for money:

[T]here is nothing harder to estimate than a writer’s time, nothing harder to keep track of. There are moments — moments of sustained creation — when his time is fairly valuable; and there are hours and hours when a writer’s time isn’t worth the paper he is not writing anything on.

I’ve previously mentioned this great aside, in the same vein, from his Paris Review interview:

Delay is natural to a writer. He is like a surfer — he bides his time, waits for the perfect wave on which to ride in. Delay is instinctive for him. He waits for the surge (of emotion? of strength? of courage?) that will carry him along. I have no warm-up exercises, other than to take an occasional drink.

I guess the reason writers have to clear the decks is that they never know when the “moments of sustained creation” will come, and they have to be sitting in front of the page, waiting for them — and pushing through the others.

Which is to say (and to remind myself) that I’m still finishing my novel and, apart from the day job, doing very little else. Last week’s posting flare-up was an anomaly.

See (and hear) also: a 1942 interview with White on One Man’s Meat, rare recordings of the author reading from Charlotte’s Web and The Trumpet of the Swan, and his response to a fan who wanted to visit him at his farm: “Thank you for your note about the possibility of a visit. Figure it out. There’s only one of me and ten thousand of you. Please don’t come.”

Lorin Stein’s first issue of The Paris Review is, like the beautifully redesigned website and the books he’s edited, elegant, edgy, and surprising, an unusual but cohesive mix of writing characterized by intelligence, precision and, frequently, humor.

Lorin Stein’s first issue of The Paris Review is, like the beautifully redesigned website and the books he’s edited, elegant, edgy, and surprising, an unusual but cohesive mix of writing characterized by intelligence, precision and, frequently, humor.

As Stein observes in his Editor’s Note, by the time The Paris Review was founded in 1953, critics had already “been lamenting the Death of the Novel, and fiction in general, since the end of World War II.” The magazine sought to — and did — prove them wrong “not by argument, but by example,” finding and publishing “not things they considered competent, or merely worthy, but things they actually loved.” Because Stein has always done the same, he and the editorial team he’s assembled are a natural fit.

The issue includes an interview with the great Norman Rush, who discusses his early experimental efforts and the evolution of his writing process and invites his wife Elsa into the conversation as he reveals how deeply involved, on myriad levels, she is in his work. “[H]er patience with my arcane fiction was part of a greater patience, over a sort of battle we waged for years,” he says. “Some couples don’t ask much of one another after they’ve worked out the fundamentals of jobs and children. Some live separate intellectual and cultural lives, and survive, but the most intense, most fulfilling marriages need, I think, to struggle toward some kind of ideological convergence.”

Rush’s sentiments about the difficulty and sorrow of endings — “Dostoyevsky died still intending to write another volume of The Brothers Karamazov. It’s like a knife in my heart that he didn’t.” — find a partial echo in the Michel Houellebecq interview: “the last pages of The Brothers Karamazov: not only can I not read them without crying, I can’t even think of them without crying.”

Sam Lipsyte always makes me cackle, and his new story, “The Worm in Philly,” is my favorite so far (though I have yet to get to The Ask). If you’re unsure whether to read Lydia Davis’ new translation of Madame Bovary, the delightful “Ten Stories From Flaubert” will stoke your appetite. And April Ayers Lawson’s “Virgin,” a fascinating and nuanced portrait of frustrated male desire, is as frankly sexual in its way as any of Mary Gaitskill’s work, and somehow also — I know this sounds paradoxical — sort of old-fashioned in its restraint.

But it was John Jeremiah Sullivan’s affectionate reminiscence of the Southern writer Andrew Lytle that made me tear up on the subway and almost miss my stop. Born in Kentucky and raised in Indiana, Sullivan knows and masterfully, self-mockingly evokes the problem of the semi-Southerner, of growing up a Yankee and being “aware of a nowhereness to my life … a physical ache.” By the time he enrolled at the University of the South, he says, “Merely to hear the word Faulkner at night brought forth gusty emotions.”

<

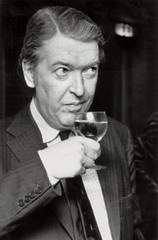

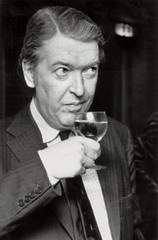

Excerpting Kingsley Amis’ Everyday Drinking at length in any discussion thereof is both crucial and inadequate: crucial because nothing anyone could say about it would be as entertaining as the text itself, and inadequate because the only way to convey how consistently funny it is would be to reproduce the book verbatim.

Excerpting Kingsley Amis’ Everyday Drinking at length in any discussion thereof is both crucial and inadequate: crucial because nothing anyone could say about it would be as entertaining as the text itself, and inadequate because the only way to convey how consistently funny it is would be to reproduce the book verbatim.

In their persistent humor and charm and their seeming effortlessness, these essays remind me of the best of Twain’s.

You may have come across a condensed version of Amis’ hangover recovery advice in the Daily Mail a couple years ago. I enjoyed it at the time, but now, having read that section of the book in full, I’m aghast that so much was lost in the cutting. Couldn’t the editors have omitted some of the day’s news instead?

Amis advocates a two-pronged approach to hangover recovery: the physical, and the metaphysical. The third step in his treatment of the metaphysical hangover (M.H.) entails embarking on either the M.H. Literature Course or the M.H. Music Course, or, if necessary, both in succession. “The structure of both Courses … rests on the principle that you must feel worse emotionally before you start to feel better. A good cry is the initial aim.”

Amis’ Rx for hangover reading:

Begin with verse, if you have any taste for it. Any really gloomy stuff that you admire will do. My own choice would tend to include the final scene of Paradise Lose, Book XII, lines 606 to the end, with what is probably the most poignant moment in all our literature coming at lines 624-6. The trouble here, though, is that today of all days you do not want to be reminded of how inferior you are to the man next door, let alone to a chap like Milton. Safer to pick someone less horribly great. I would plump for the poems of A.E. Housman and/or R.S. Thomas, not that they are in the least interchangeable. Matthew Arnold’s Sohrab and Rustum is good, too, if a little long for the purpose.

Switch to prose with the same principles of selection. I suggest Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It is not gloomy exactly, but its picture of life in a Russian labour camp will do you the important service of suggesting that there are plenty of people about who have a bloody sight more to put up with than you (or I) have or ever will have, and who put up with it, if not cheerfully, at any rate in no mood of self-pity.

Turn now to stuff that suggests there may be some point to living after all. Battle poems come in rather well here: Macaulay’s Horatius, for instance. Or, should you feel that this selection is getting a bit British (for the Roman virtues Macaulay celebrates have very much that sort of flavour), try Chesterton’s Lepanto. The naval victory in 1571 of the forces of the Papal League over the Turks and their allies was accomplished without the assistance of a single Anglo-Saxon (or Protestant). Try not to mind the way Chesterton makes some play with the fact that this was a victory of Christians over Moslems.

By this time you could well be finding it conceivable that you might smile again some day. However, defer funny stuff for the moment. Try a good thriller or action story, which will start to wean you from self-observation and the darker emotions: Ian Fleming, Eric Ambler, Gavin Lyall, Dick F

I’ve been gearing up for Martin Stannard’s Muriel Spark biography by revisiting (and reading more of) her own fiction, which was evidently treated as unsaleable for much of her career. In 1999, she told Janice Galloway:

“I used to be sold the idea that what I was writing was some little cult and people wouldn’t buy the things. Publishers used to go on that way until I just got rid of them.”

“How?”

“I got new publishers.”

Here, for no particular reason except that I’m caught up in scrutinizing her work, are the first sentences of nine of her twenty-two books:

The Comforters: “On the first day of his holiday Laurence Manders woke to hear his grandmother’s voice below.”

Memento Mori: “Dame Lettie Colston refilled her fountain pen and continued her letter: ‘One of these days I hope you will write as brilliantly on a happier theme. In these days of cold war I do feel we should soar above the murk & smog & get into the clear crystal.’”

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie: “The boys, as they talked to the girls from Marcia Blaine School, stood on the far side of their bicycles holding the handlebars, which established a protective fence of bicycle between the sexes, and the impression that at any moment the boys were likely to be taken away.”

The Girls of Slender Means: “Long ago in 1945 all the nice people in England were poor, allowing for exceptions.”

The Driver’s Seat: “And the material doesn’t stain,” the salesgirl says.

Loitering with Intent: “One day in the middle of the twentieth century I sat in an old graveyard which had not yet been demolished, in the Kensington area of London, when a young policeman stepped off the path and came over to me.”

The Only Problem: “He was driving along the road in France from St. Dié to Nancy in the district of Meurthe; it was straight and almost white, through thick woods of fir and birch.”

A Far Cry from Kensington: “So great was the noise during the day that I used to lie awake at night listening to the silence.”

The Finishing School: “You begin,” he said, “by setting your scene. You have to see your scene, either in reality or in imagination.”

Iris Murdoch’s novels were deeply informed — if not consciously shaped by — her readings in philosophy. Walker Percy found a theoretical framework for his fiction in Kierkegaard, who also influenced Kafka.

Iris Murdoch’s novels were deeply informed — if not consciously shaped by — her readings in philosophy. Walker Percy found a theoretical framework for his fiction in Kierkegaard, who also influenced Kafka.

And Donald Barthelme urged his students to choose their “literary fathers” carefully, and to be well-versed in philosophy. Hiding Man, Tracy Daugherty’s biography, suggests that reading Beckett and the existentialists gave Barthelme confidence that the kind of stories he wanted to write were possible.

Don dropped by Guy’s Newsstand…. and found a copy of Theatre Arts. In it was Waiting for Godot. He stood there and read the whole thing.

That evening, when he took Helen out to dinner, he brought the magazine with him. She had already read the play. “I found it exciting but did not see the implications for Don,” she says. “He was deeply moved and ecstatic about the language…. Each time we were in a bookstore after this, Don looked for work by Beckett and immediately read whatever he found. It seemed that from the day he discovered Godot, Don believed he could write the fiction he imagined.” It would be heavily ironic, and he could “use his wit and intellect in a way that would satisfy him.”

Of course, Don’s breakthrough wasn’t that easy. “The problem is … to do something that’s credible after Beckett, as Beckett had to do something that was credible after Joyce,” he said years later.

Initially, though, the excitement! Waiting for Godot showed Don that philosophy could become drama, almost directly, without the interference of plot, setting, and so on. By stripping away fiction’s stock devices, Beckett focused on consciousness. He could animate the intentionality at the heart of awareness….

[H]is discovery of Beckett and his philosophical studies were guiding him away from vague attempts at an “unlove” story. He was forming a firmer aesthetic. He grounded his magazine editing in philosophy, too, especially in existentialism as it evolved under John Paul Sartre.

I’m fascinated and inspired by this interconnectedness, but also a little wary of it. Whenever I feel philosophical or political axe-grinding creeping into my fiction, I think of Jimmy Chen’s succinct dismissal of novels whose didactic agendas overshadow their artistic ones (though I do love Brave New World — or did, the last time I read it). Your comments are welcome.

See also Murdoch’s Existentialists and Mystics, in which she imagines Socrates saying “In philosophy, if you aren’t moving at a snail’s pace, you aren’t moving at all”; In defense of Big Ideas in fiction; and Wolcott on Barthelme.

I don’t measure fiction by the same aesthetic metrics as James Wood, but any impassioned Wood critique is far superior to a hundred polite hand-clappings. And it’s especially interesting to see him building in the latest New Yorker on the grudgingly admiring essay on J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace (”a very good novel, almost too good a novel”) that appeared in The Irresponsible Self, and extending some of the theses he began to formulate in his review of Elizabeth Costello.

In Coetzee’s novels, Wood observes, “emotions like shame, guilt, and disgrace surge beyond rational discussion.” Placing Diary of a Bad Year in the larger context of the Nobel laureate’s body of work, he argues that “Coetzee has always been an intensely metaphysical novelist, and in recent years the religious coloration of his metaphysics has become more pronounced.”

The pieties of current criticism are supposed to forbid one to inquire about Coetzee’s relation to this strain of theology. We are warned that it is naïve to confuse author and character, even when — especially when — that character is also a novelist. But if Coetzee’s novels deflect such inquiries, they also invite them, not least because of the provoking extremity, even irrationality, of their ideas. In the last entry of this novel, “On Dostoevsky,” Señor C writes:

I read again last night the fifth chapter of the second part of The Brothers Karamazov, the chapter in which Ivan hands back his ticket of admission to the universe God has created, and found myself sobbing uncontrollably.

It is not the force of Ivan’s reasoning, he says, that carries him along but “the accents of anguish, the personal anguish of a soul unable to bear the horrors of this world.” We can hear the same note of personal anguish in Coetzee’s fiction, even as that fiction insists that it is offering not a confession but only the staging of a confession. His books make all the right postmodern noises, but their energy lies in their besotted relationship to an older, Dostoyevskian tradition, in which we feel the desperate impress of the confessing author, however recessed and veiled.

I’ve yet to get my hands on a copy of Diary of a Bad Year, but Wood’s critique puts me in mind of Peter Brooks’ Troubling Confessions: Speaking Guilt in Law and Literature, the most useful work of criticism I own, and the only one I revisit annually.

The book bears an approving dust jacket blurb from J.M. Coetzee, and cites him throughout. Here’s a passage Brooks quotes from “Confession and Double Thoughts: Tolstoy, Rousseau, Dostoevsky“:

The end of confession is to tell the truth to and for oneself. The analysis of the fate of confession that I have traced in three novels by Dostoevsky indicates how skeptical Dostoevsky was, and why he was skeptical, about the variety of secular confession that Rousseau and, before him, Montaigne attempt. Because of the nature of consciousness, Dostoevsky indicates, the self cannot tell the truth to itself and come to rest without the possibility of self-deception. True confession does not come from the sterile monologue of the self or from the dialogue of the self with its own self-doubt, but … from faith and grace.

The image is of Dostoyevsky’s notes for chapter 5 of The Brothers Karamazov.

I couldn’t tell who the kids across the aisle were laughing at on the subway the other night, until I remembered that the cover is affixed upside-down to my copy of Angela Carter’s Wise Children. I must have looked like a madwoman, hiding behind it, reading so intently.

I couldn’t tell who the kids across the aisle were laughing at on the subway the other night, until I remembered that the cover is affixed upside-down to my copy of Angela Carter’s Wise Children. I must have looked like a madwoman, hiding behind it, reading so intently.

In honor of the forthcoming Wise Children reissue, and while we’re on the subject of the long train commute, here’s a little gentrification rant from the novel’s opening:

Once upon a time, you could make a crude distinction, thus: The rich lived amidst pleasant verdure in the North speedily whisked to exclusive shopping by abundant public transport while the poor eked out miserable existences in the South in circumstances of urban deprivation condemned to wait for hours at windswept bus-stops while sounds of marital violence, breaking glass and drunked song echoed around and it was cold and dark and smelled of fish and chips. But you can’t trust things to stay the same. There’s been a diaspora of the affluent, they jumped into their diesel Saabs and dispersed throughout the city. You’d never believe the price of a house round here, these days. And what does the robin do then, poor thing?

Bugger the robin! What would have become of us if Grandma hadn’t left us this house?

When I asked Alex Ross if I could excerpt the epilogue (below) of his eloquent and persuasive The Rest is Noise: Listening to the 20th Century, he surprised me by saying it was the section he reworked the most. The conclusion follows so perfectly from the history and arguments that precede it, I imagined him sitting down and dashing the finale off in an afternoon. But of course, this is what good writers do: they go over their arguments until the effort doesn’t show.

If you’d like to win a copy of

The Rest is Noise

, email me at maud [at] maudnewton [dot] com between now and 12:59 p.m. EST with the words “Alex Ross” in the subject line. All entries will be assigned numbers based on the order received, and a randomizer will choose the winner.

Extremes become their opposites in time. Schoenberg’s scandal-making chords, totems of the Viennese artist in revolt against bourgeois society, seep into Hollywood thrillers and postwar jazz. The supercompact twelve-tone material of Webern’s Piano Variations mutates over a generation or two into La Monte Young’s Second Dream of the High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer. Morton Feldman’s indeterminate notation leads circuitously to the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life.” Steve Reich’s gradual process infiltrates chart-topping albums by the bands Talking Heads and U2. There is no escaping the interconnectedness of musical experience, even if composers try to barricade themselves against the outer world or to control the reception of their work. Music history is too often treated as a kind of Mercator projection of the globe, a flat image representing a landscape that is in reality borderless and continuous.

Extremes become their opposites in time. Schoenberg’s scandal-making chords, totems of the Viennese artist in revolt against bourgeois society, seep into Hollywood thrillers and postwar jazz. The supercompact twelve-tone material of Webern’s Piano Variations mutates over a generation or two into La Monte Young’s Second Dream of the High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer. Morton Feldman’s indeterminate notation leads circuitously to the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life.” Steve Reich’s gradual process infiltrates chart-topping albums by the bands Talking Heads and U2. There is no escaping the interconnectedness of musical experience, even if composers try to barricade themselves against the outer world or to control the reception of their work. Music history is too often treated as a kind of Mercator projection of the globe, a flat image representing a landscape that is in reality borderless and continuous.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the impulse to pit classical music against pop culture no longer makes intellectual or emotional sense. Young composers have grown up with pop music ringing in their ears, and they make use of it or ignore it as the occasion demands. They are seeking the middle group between the life of the mind and the noise of the street. Likewise, some of the liveliest reactions to twentieth-century and contemporary classical music have come from the pop arena, roughly defined. The microtonal tunings of Sonic Youth, the opulent harmonic designs of Radiohead, the fractured, fast-shifting time signatures of math rock and intelligent dance music, the elegaic orchestral arrangments that underpin songs by Sufjan Stevens and Joanna Newsom: all these carry on the long-running conversation between classical and popular traditions.

Björk is a modern pop artist deeply affected by the twentieth-century classical repertory that she absorbed in music school — Stockhausen’s electronic pieces, the organ music of Messiaen, the spiritual minimalism of Arvo Pärt. If you were to listen blind to Björk’s “An Echo, A Stain,” in which the singer declaims fragmentary melodies against a soft cluster of choral voices, and then move on to Osvaldo Golijov’s song cycle Ayre, where pulsating dance beats underpin multi-ethnic songs of Moorish Spain, you might conclude that Björk’s was the classical composition and Golijov’s was something else. One possible destination for twenty-first-century music is a final “great fusion”: intelligent pop artists and extroverted composers speaking more or less the same language.

Sterner spirits will undoubtedly continue to insist on fundamental differences in musical vocabulary, attaching themselves to the venerable orchestral and operatic traditions of the Baroque, Classical, and Romantic eras or the now equally venerable practices of twentieth-century modernism. Already in the first years of the new century composers have produced works of monumental character that invite comparison to the symphonies of Mahler and the operas of Strauss. Thomas Adés’s The Tempest, first heard at Covent Garden in 2004, shows that a composer can still write a grand opera of ornate design and airy power in an atomizing digital age. The following year saw the premiere of John Adam’s Doctor Atomic, an opera about the testing of the first atomic bomb. Holding his lyricism in reserve, Adams marshals a ghoulish army of twentieth-century styles to summon the awe and dread of the atomic morning. Georg Friedrich Haas’s sixty-five-minute ensemblie piece in vain may mark a new departure in Austro-German music, joining spectral harmony to a vast Brucknerian structure.

If twenty-first-century composition appears to have a split personality — sometimes intent on embracing everything, sometimes longing to be lost to the world — its ambivalence is nothing new. The debate over the merits of engagement and withdrawal has gone on for centuries. In the fourteenth century, Ars Nova composers engendered controversy by inserting secular tunes into the Mass Ordinary. Around 1600, Monteverdi’s forcefully melodic style sounded crude and libertine to adherents of rule-bound Renaissance polyphony. In nineteenth-century Vienna, the extroverted brilliance of Rossini’s comic operas was judged against the inward enigmas of Beethoven’s late quartets. Composition only gains power from failing to decide the eternal dispute. In a decentered culture, it has the chance to play a kind of godfather role, able to assimilate anything new because it has assimilated everything in the past.

Composers may never match their popular counterparts in instant impact, but, in the freedom of their solitude, they can communicate experiences of singular intensity. Unfolding large forms, engaging the complex forces, traversing the spectrum from noise to silence, they show the way to what Claude Debussy once called the “imaginary country, that’s to say one that can’t be found on the map.”

American Food Writing: An Anthology with Classic Recipes is a fun book to have on hand under any circumstances. But if you’re going to prepare turkey tomorrow, it could be a crucial resource.

American Food Writing: An Anthology with Classic Recipes is a fun book to have on hand under any circumstances. But if you’re going to prepare turkey tomorrow, it could be a crucial resource.

Thanksgiving, for reasons I won’t bore you with here, was my least favorite day of the entire year growing up. I lay awake worrying about it months in advance. But one year I somehow escaped my parents and their acrimonious festivities and celebrated the holiday with a Cuban friend’s family.

Que rico, people. Gone were the foul sweet potatoes with marshmallow, the “ambrosia” (has there ever been a more misleadingly-named dish?), the squash cooked to the point of disintegration, and the turkey tough enough to be the remains of last year’s carcass.

There were frijoles negros and maduros — comfort food to any Miamian, regardless of ethnicity — and piles and piles of other appetizers and treats. And then there was the bird, succulent and garlicky, with a little hint of citrus. I can’t even begin to tell you how the Cuban roast turkey dwarfs its Anglo counterpart.

The secret is the mojo. And in the updated edition of American Food Writing, writer Ana Menéndez supplements a delightful essay about her Cuban family’s first Miami Thanksgivings with a recipe for this magical marinade. Here’s an excerpt from her piece:

[C]hange, always inevitable and irrevocable, came gradually. As usual, it was prefigured by food. One year someone brought a pumpkin pie from Publix. It was pronounced inedible. But a wall had been breached. Cranberry sauce followed. I myself introduced a stuffing recipe (albeit composed of figs and prosciutto) that to my current dismay became a classic. Soon began the rumblings about pork being unhealthy. And besides, the family was shrinking…. A whole pig seemed suddenly an embarrassing extravagance, a desperate and futile grasping after the old days.

And so came the turkey. I don’t remember when exactly. I do recall that at the time, I had been mildly relieved. I had already begun to develop an annoyance with my family’s narrow culinary tastes — which to me signaled a more generalized lack of curiosity about the wider world. I had not yet discovered M.F.K. Fisher, and at any rate, I wasn’t old enough to understand that a hungry man has no reason to play games with his palate. I remember that soon after the first turkey appeared, there was much confusion over how to cook this new beast. The problem was eventually resolved by treating the bird exactly as if it were a pig. In went the garlic and the sour orange, the night-long mojo bath. When this didn’t seem quite enough to rid the poor turkey of its inherent blandness, someone came up with the idea of poking small incisions right into the meat and stuffing them with slivered garlic. Disaster, in this way, was mostly averted. And to compliment the cook one said, “This tastes just like roast pork.”

Pick up the book for the recipe, or look at

some examples online.

I’m trying not to go anywhere, drink too much, or read any books until I get past that deadline later this month, but a copy of Victor LaValle’s The Ecstatic just arrived, and I made the mistake of opening it.

I’m trying not to go anywhere, drink too much, or read any books until I get past that deadline later this month, but a copy of Victor LaValle’s The Ecstatic just arrived, and I made the mistake of opening it.

It’s hard to put down a novel that starts like this:

They drove a green rented car into central New York State to find me living wild in my apartment. Wearing shattered glasses and my hair a giant cauliflower-shaped afro on my head. I was three hundred and fifteen pounds. I was a mess, but the house was clean. They knocked and when I opened the front door there were three archangels on my stoop. My sister rubbed my ear when I cried. She whispered, — Why don’t you go put on clothes?

My family took me home to Queens and kept me in the basement. When I tried to go outside alone, they discouraged it. My sister led me by the hand when walking to the supermarket. Mom cut my meat at the dinner table. They treated me like what some still refer to as a Mongoloid. A few days of this is tenderness, but two weeks seems more like punishment. The spirit of blame stooped in a corner.

Their concern was wonderful, but the condescension was deadly. And surprising. Before opening the front door to them I really thought my life was full of pepper.

Three weeks after coming back to Rosedale I cooked a big, red breakfast for my family just to prove that I could. Not only to them, but to myself. It was September 25, 1995. I remember certain dates to organize and understand my disaster. Without them my mind is a mass grave.

It was a red breakfast because I added ketchup to the eggs when scrambling them. And to the bacon as it curled in the pan. Call me tasteless, but ketchup is the only seasoning I need.

I was so nervous that I even dressed up that morning. This bright purple suit that was loose on me and hid my tits. Made me look like a two-hundred-fifty-pound man.

Our oven was so hot I had to watch I didn’t sweat into the food. Wiped my forehead with my tie. I pulled butter from the fridge to set next to a plate of toast and if this didn’t make them happy then I was out of ideas.

But they didn’t appear. I waited a long time….

They’d hid in the bathroom. Mom leaned against the sink while Grandma rested on the toilet and my sister, Nabisase, sat on the rim of the tub. Three versions of the same woman — past, present and future — huddled in one room. With the door partway shut I was unseen and apart from them.

Mom whispered, –We should go to him.

– Yes. Grandma agreed, but they stayed there.

My family was afraid of me.

I expected more sympathy, actually, because I wasn’t the first one in my bloodline to go zipper-lidded. You should’ve seen when my mother tobogganed naked through Flushing Meadow Park in 1983. Four police carried her to the hospital wrapped in their jackets. Parents on the hill thought Mom was a hump-starved fiend out to abduct their children. Her illness often made her frenzied sexually. Whenever she relapsed the woman was an open womb, but Haldol had stabilized Mom’s mind for years.

There was my Uncle Isaac, too, who walked from New York to the Canadian border in 1986, and emptied out his brain pan with a rifle. So when they discovered me in that Ithaca apartment Mom and Grandma recognized the situation. Their boy had become a narwhal.

At the end of his novel, LaValle offers this explanation of the title:

An ecstatic is a term once used in places as diverse as seventeenth-century London and nineteenth-century Bengal to describe people whose actions were impossible to understand. The average person saw a man or woman who suddenly spoke gibberish or refused to bathe; a person they knew became a stranger. Seemingly overnight. Some saw these transformed people as possessed, or touched by God. Calling them ecstatics was a way to explain the unexplainable. Now, it seems likely that many of the ecstatics were mentally ill. I learned this curious history long before I finished my novel, but in the way it intertwined religious faith, the human need to know the unknowable, and mentall illness, it fit….

I’m going to have to force myself to put The Ecstatic to the side for a while, because it sounds like there could be too much overlap of with the concerns of my own book, and I don’t want to steal ideas.

(I should mention that LaValle is a friend of a friend, and someone to whom I once spent an hour evangelizing about The End of the Affair, but it was only recently, when I happened across his comments on Kenzaburo Oe’s 1958 novella “Prize Stock,” collected in Teach Us to Outgrow Our Madness, that I realized I had to read his fiction.)

The Paris Review Interviews Volume II appears later this month. I’m already dog-earing my copy, so you should probably brace for an onslaught of excerpts.

The Paris Review Interviews Volume II appears later this month. I’m already dog-earing my copy, so you should probably brace for an onslaught of excerpts.

What separates the best of these interviews from your average author chat is that the conversations take place in person, over days or months or years. The interviewer and writer stake out positions. They return time and again, like old friends (or enemies), to debates and ideas they know well. The final interviews, culled from all of this material, are a kind of fiction. All the clichés and plot summaries and daft or lecherous remarks stay in the cutting room, and we are able to continue believing that the authors we revere are effortlessly wise and entertaining.

I haven’t read García Márquez in well over a decade. (Back then I got two-and-a-half novels in before the rhapsody faded.) But I was encouraged to learn of his preoccupation with getting the very beginning of his novels just right.

One of the most difficult things is the first paragraph. I have spent many months on a first paragraph, and once I get it, the rest just comes out very easily. In the first paragraph you solve most of the problems with your book. The theme is defined, the style, the tone. At least, in my case, the first paragraph is a kind of sample of what the rest of the book is going to be. That’s why writing a book of short stories is much more difficult than writing a novel. Every time you write a short story, you have to begin all over again.

And here he is on the difference between inspiration and intuition:

Inspiration is when you find the right theme, one that you really like; that makes the work much easier. Intuition, which is also fundamental to wriing fiction, is a special quality that helps you to decipher what is real without needing scientific knowledge or any other special kind of learning. The laws of gravity can be figured out much more easily with intuition than anything else. It’s a way of having experience without having to struggle through it. For a novelist, intuition is essential. Basically it’s contrary to intellectualism, which is probably the thing that I detest most in the world — in the sense that the real world is turned into a kind of immovable theory. Intuition had the advantage that either it is, or it isn’t.

For an excerpt from the Toni Morrison interview, also contained in the second volume,

go here. If you haven’t picked up the first book yet, come back on October 30 (the pub date). I’ll be giving away copies of both volumes then.

One of my favorite law school classes was a legal history seminar that explored the influence of Methodism and other early Evangelical sects on the development of our legal system. Although I grew up in a whacked-out fundamentalist household, I didn’t fully understand the roots of Evangelical Christianity until I took that class. Good thing, I thought then, that we now understand the importance of separation between church and state.

I’ve just started to read D. Michael Lindsay’s Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite. The introduction provides both a good explanation of what an Evangelical is — they’re not all holy rollers like the dude with his arms up in the Economist photo (above) — and a depressing look at how fully some of their most extreme representatives have infiltrated our political system and other institutions of power. I’m posting the intro here with permission.

Atop 30 Rockefeller Plaza in one of Manhattan’s most celebrated ballrooms, media mogul Rupert Murdoch stepped up to a microphone. It was September 2004, and gathered before him was a Who’s Who of the New York publishing elite. “When an author sells a million copies of his book, we think he’s a genius. When he sells twenty million, we say we’re the geniuses.”

Murdoch was introducing Rick Warren, a folksy Southern Baptist preacher from suburban southern California. As head of the media conglomerate that published Warren’s The Purpose-Driven Life, Murdoch had much to smile about. The book had become the bestselling work of nonfiction in history (other than the Bible) and had been translated into more than fifty different languages. Long before this, Warren had made a name for himself in evangelical circles. An earlier book, The Purpose-Driven Church, had sold a million copies, and over the years thousands of pastors had attended conferences to hear Warren and his staff talk about their approach to church growth.

That evening Warren had invited several of his friends from California to the party, and a handful of fellow evangelicals from the East Coast were in attendance as well. This was Warren’s “coming out” party — a recognition that he was now part of the nation’s elite. As I spoke to Warren’s wife, Kay, she casually mentioned that she had met Dan Rather’s wife the night before for dinner. During the party I spotted several Fortune 500 CEOs around the room. Warren was now not just a religious leader but a public leader, endowed with responsibility and influence far beyond the evangelical world.

The mood was festive and lively, but the two groups didn’t mix all that well. I was there at the invitation of a friend who knew I was doing research on America’s leadership and evangelicals. I introduced myself to an editor from another publishing house. Upon hearing that I was from Princeton, she assumed I was part of the publishing crowd. “Do you know any of these evangelicals that are here? I’m dying to meet one,” she asked.

“I do,” I replied, and then introduced her to an evangelical friend who was standing nearby. Mark, a successful businessman, had lived in New York for quite some time. He, like her, had graduated from Yale, so I used that as a point of connection when introducing the two. As I turned to continue mingling, I heard her ask: “Are there many evangelicals at Yale these days?”

It’s a good question. Evangelicals are the most discussed but least understood group in America today. National surveys show that their numbers have not grown dramatically in recent decades, but over that same time they have become significantly more prominent. Everything from presidential campaigns to student groups in the Ivy League has been linked to rising evangelical influence. Social groups can gain power in a variety of ways — by voting a candidate into the Oval Office, by assuming leadership of powerful corporations, or by shaping mainstream media. Evangelicals have done them all since the late 1970s, and the change has been extraordinary. But no one has explained what these developments mean — for the evangelical movement or for America.

Much of the twentieth century was spent disentangling religion from public life. Commerce and piety were once seen as complements to one another. But that connection dissolved with the rise of modern corporations, as the personal was divorced from the professional. Americans embraced pluralism in the workplace, public schools, and civic life, and these institutions worked to minimize sectarian differences among workers and citizens. In the process, religion lost some of its influence, becoming just one of many sources for individual and national identity. Gradually, religion was relegated to the private, personal sphere.

Yet even as this arrangement finally became taken for granted in many quarters of American life, opposing perspectives were emerging. In the 1970s, conservative Christians, many of whom had sequestered themselves in a distinct subculture, began returning to the cultural mainstream. Initially, they met with only limited success, and many observers ignored their entrepreneurial creativity and strong resolve to change America. Also, few connected evangelicals’ activism in politics with activism in other spheres, even though evangelicals regard these as more important.

Theirs is an ambitious agenda: to bring Christian principles to bear on a range of social issues. It is a vision for moral leadership, a form of public influence that is shaped by ethics and faith while also being powerful and respected. In truth, their vision is much less — and at the same time significantly more — than skeptics and critics think. To the extent that the activities of evangelical leaders point to a cohesive vision, it is not a political or cultural agenda but one grounded in religious commitment. Fundamentally, evangelicals feel compelled to share with others what they believe is the best way to make peace with God. For them, one’s relationship with the divine is primary; all other issues are secondary. This is not new, and, in fact, it is a much smaller vision for society, one that involves changing one person at a time. What is unique to the current moment is the number of high-ranking leaders who have experienced that change themselves, either before they rose to power or while in public leadership. For many of them, the evangelical imperative to bring faith into every sphere of one’s life means that they cannot expunge faith from the way they lead, as some would prefer. In this way, the evangelical vision is sweeping and significantly more comprehensive than outside observers realize. This is much more than a campaign to win the White House or a call for Hollywood to produce family-friendly entertainment. It is a way of life that has gripped the hearts and minds of leaders around the country, and it is not likely to go away anytime soon.

It is not every day that a media mogul throws a party for a Southern Baptist preacher, but things like that have been happening more and more. Harvard Divinity School, not always the most welcoming place for evangelicals, now has an endowed chair in evangelical theological studies. Every person who has been elected president of the United States since 1976 has been affiliated with evangelicalism in one way or another. Evangelicals have been the driving force behind debates over abortion, same-sex marriage, and foreign affairs. Indeed, they are prominent in virtually every aspect of American life today. How have evangelicals — long lodged in their own subculture and shunned by the mainstream — achieved significant power in such a short time? That is the question this book seeks to answer.

What’s an Evangelical?

There are many streams of religious tradition that flow into contemporary American evangelicalism, and those who call themselves evangelicals belong to a wide variety of Protestant denominations — and many to no denomination at all. Even some Catholics consider themselves evangelical. Despite these various tributaries and the different ways evangelicalism has been defined, there is a remarkable consensus among evangelicals about the Bible, God, Jesus, the Holy Spirit, evangelism, Christian living, and the church. Evangelicals are Christians who hold a particular regard for the Bible, embrace a personal relationship with God through a “conversion” to Jesus Christ, and seek to lead others on a similar spiritual journey. I define an evangelical as someone who believes (1) that the Bible is the supreme authority for religious belief and practice, (2) that he or she has a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, and (3) that one should take a transforming, activist approach to faith.

Evangelicalism is not just a set of beliefs; it is also a social movement and an all-encompassing identity. Because evangelicals must consciously choose their faith — ”accepting” Jesus, in the evangelical vernacular — they often have a stronger attachment to faith than people who simply inherit their parents’ religion. Within many evangelical congregations, when a person converts, he or she is asked to make a profession of faith that refers to Jesus as “Lord of my life,” and the minister often responds by challenging the new believer to dedicate every part of his or her life to God. In other words, evangelicalism is a religious identity but also much more: Evangelicals must live out their faith every moment of their lives, not just on Sunday morning. Typically, this includes talking with others about one’s faith — ”witnessing” — but it also includes things like feeding the hungry and caring for the sick.

As America has become more religiously diverse, evangelicals have begun acting on their faith in more public ways. Evangelicals see the world largely in terms of good and evil and believe that one overcomes evil through spiritual discipline — praying, studying scripture, and the like. This is what fuels their moral conviction and moves them to action. The current public activism of evangelicals is not unlike evangelicalism of previous generations. A desire to reform society spurred evangelical political involvement in the nineteenth century, and we will see several examples from the twentieth century in the chapters ahead. As one senior White House staffer put it, for him it is where “you get your moral passion furnished, your depth of commitment, because you think it’s true and right.”

Evangelicalism also encourages spiritual improvisation and individualism. Evangelicals are urged to “work out their faith” (as stated in Philippians 2), which typically entails regular spiritual disciplines like worship, prayer, and Bible study. The individualistic component of evangelicalism is important because it allows very different ways of acting on one’s faith. It is why evangelicals can, in good conscience, arrive at very different opinions about how to act on one’s faith even though they may rely on the same interpretation of the Bible and share religious convictions and sensibilities. (In this book, I use “convictions” to refer to norms, reasoning, and ideology — matters of belief. “Sensibilities” refers to matters of religious practice — routines, demeanor, perceptions, and way of life.) Also, evangelicalism does not have a religious hierarchy, which permits believers the freedom to disagree with their pastors and, on occasion, church teaching.

Evangelicals further believe that they hold a responsibility to care for society. This notion of being entrusted with a mandate to work for the “common good” is seen as a covenant between God and His people. In the Bible, this covenant referred to an arrangement with the Jews, but evangelicals — along with most other Christians — believe the New Testament extended that covenant to them. This provides evangelicals with hope and encouragement to persevere in trying to overcome evil. Things may be wrong in the world, but they, working with God, can set the world aright.

These beliefs have been critical to evangelicalism’s success as a social movement. While evangelicals hold many different opinions, they have remained remarkably united in their campaign to interject moral convictions into American public life. They aim for their leaders to exercise “moral leadership” informed by faith and are guided by a particular moral vision of the way things ought to be.

Movements depend upon more than individuals; they need resources like money and power, and these resources are usually channeled through organizations. American evangelicalism has spawned a large number of voluntary associations and organizations, ranging from publishing houses to educational institutions to social service agencies. These organizations serve as the movement’s skeleton, connected by ligaments of social networks that join leaders in common cause. Through these networks evangelicals can talk about their public activism, which both mobilizes people to act and maintains momentum once their work has begun. We will look at these institutional and expressive dimensions of American evangelicalism and how they have contributed to the movement’s forward momentum. The goal of this movement — as in any movement — is to advance: to secure legitimacy and then to achieve shared objectives.

American Evangelicalism: A Short History

In the nineteenth century, American evangelicalism was so influential that, in the words of one historian, “it was virtually a religious establishment.” Conservative Protestants populated the faculties of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Evangelicals were also active in politics, helping to drive the temperance and women’s suffrage movements as they had done decades earlier with abolitionism. But forces soon began to emerge to challenge the evangelical establishment, first in the academy and then in wider society. At places like Harvard, higher biblical criticism and scientific naturalism put evangelical intellectuals to the test. At the same time, strictly nonsectarian institutions such as Johns Hopkins University were established. Evangelical dominance was also threatened demographically, as waves of new immigrants began to reach American shores. Roman Catholics and Jews emigrated from eastern and southern Europe, making America much more religiously diverse. Urbanization and industrialization posed novel challenges to the existing welfare infrastructure. Soon, religious bodies were no longer able to meet the growing need for social services, and the federal government and expanding corporations were called upon to provide them.

Nonetheless, in the early twentieth century theological conservatives fought for the continued relevance of their faith. The turning point came at the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925. Though they won in court, “fundamentalists,” as they were called by then, were ridiculed in the national media as reactionary and anti-intellectual. As a result, they set aside many of their goals for transforming society and turned their energies inward toward their own religious communities. In what has been called the “Great Reversal,” they withdrew into pessimism and separatism. Although they continued to generate new organizations, they separated from the cultural mainstream and maintained strong boundaries between themselves and wider society. Dancing, smoking, wearing makeup, and playing cards were deemed improper, and a legalistic attention to avoiding them became hallmarks of fundamentalism.

In 1942, the Reverend Harold J. Ockenga of Boston’s Park Street Congregational Church convened a group of religious leaders for a meeting. These “neo-evangelical” leaders, including Billy Graham, wanted to enter the public square again without abandoning their religious identity. They also sought to recover the tradition of rigorous intellectual inquiry wedded to a religious worldview. They founded the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), and the modern evangelical movement was born.

In 1946, Carl F. H. Henry, one of the architects of modern evangelicalism, published Remaking the Modern Mind. In it, he advocated a resurrection of a faith that could “do battle in the world of ideas.” A year later, in The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism (1947), Henry urged fellow evangelicals to engage pressing social concerns like race, class, and war and leave aside internal debates over doctrinal minutiae. Repudiating the fundamentalist model of religious separatism, the NAE allowed denominations that were already part of the liberal Federal Council of Churches to join their association as well. These evangelical leaders established institutions and networks that could sustain their lofty vision. When they founded their flagship magazine, Christianity Today, in 1956, they housed it not in some suburban enclave but in an office suite overlooking the White House.

While they were committed to engaging with society, evangelicals were relatively minor players among the powerful social actors of the 1960s and early 1970s. Some evangelicals became part of a loose network of political conservatives that emerged in the wake of Barry Goldwater’s 1964 failed presidential bid. At the same time, a group of progressive evangelicals launched a news journal called The Post-American, which urged fellow believers to mobilize for social action. Jane Fonda and Malcolm X grabbed headlines much more frequently than Billy Graham or his contemporaries did. Nonetheless, Graham continued to maintain strong relations with public leaders like Presidents Johnson and Nixon. Nixon, in fact, invited Graham to be the inaugural preacher at the weekly White House church service he established.

With America’s bicentennial in 1976, evangelicals saw an opportunity to renew their commitment to public affairs, and as they saw it, “at age two hundred, the nation sought more than improvement; it longed to be born again.” That year was a turning point for American evangelicalism. First-generation leaders — like Graham and Ockenga — began to give way to new leadership. It was dubbed the “year of the evangelical” as Time and Newsweek published cover stories on the emergence of a publicly oriented form of evangelicalism. Since that time, evangelicals have become even more prominent. From the White House to Wall Street, from Hollywood to Harvard, evangelicals today can be found in practically every center of elite power and influence. When Newsweek ran its story on evangelicals in 1976, one individual — Jimmy Carter — figured prominently. When Time ran a similar cover story in 2005, the magazine profiled twenty-five leaders — and, as this book will show, they could have chosen hundreds more.

Looking at Leadership

At its core, this is a book about leadership and power. It explores the subject by looking at some of the most important people in the country and examining what drives them. Though most of us know that there are growing numbers of evangelicals in leadership today, we know virtually nothing about them. Information on evangelicalism as practiced by the masses is plentiful and accessible, but the same is not true for leaders. National surveys do not interview enough of them to draw general conclusions, and most empirical studies have not examined their religious lives. When religion is considered, it is seen only as one box to be checked and has been glaringly omitted from discussions about the personal side of public leadership. Is religion playing a greater role in public life?

To find out, I tried to interview as many evangelicals in leadership positions as I could find. There are two kinds of leaders who are evangelical: those who lead institutions within the evangelical movement — also referred to as movement leaders — and public leaders from government, business, and culture. Altogether, I spoke to 360 of them, making this the most comprehensive examination of faith in the lives of leaders alive today.

The movement leaders I interviewed included pastors at large churches, college and seminary presidents, and heads of evangelical organizations. The public leaders each held at least one leadership position of societal prominence between 1976 and 2006. They include two former presidents of the United States as well as two dozen cabinet secretaries and senior White House staffers. There are representatives from each of the five administrations in office during that time, with a significant number coming from the administration of George W. Bush. This is due, no doubt, to the prominence of evangelicals there, but it also reflects the time at which the interviews were conducted. While in office, officials are more readily available and responsive to interview requests.

From the business community, there were over one hundred chairmen, chief executives, presidents, or senior executives at large firms (both public and private), from fifteen different industries, forty-two Fortune 500 companies, and six members of the Forbes 400 wealthiest families. The leaders I interviewed were alumni, faculty, and administrators from 159 educational institutions, including every major university in the country. And there were leaders from television, film, journalism, and the visual and performing arts, as well as selected nonprofit organizations and professional sports.

This is a relatively homogeneous crowd. While the evangelical movement can include a variety of people, its leadership — like that of most social movements — does not reflect that diversity. Their ages ranged from thirty-two to ninety-three, with the average age being fifty-four. Practically all were married with between two and three children. White evangelicalism is still largely separate from the black church, and almost all of the leaders I interviewed are white. Just 10 percent of the public leaders I interviewed are women, underscoring the dominance of men in America’s elite ranks. These include women who have held senior positions in government (such as Karen Hughes), business (such as Borders president Tami Heim and Enron executive and “whistle-blower” Sherron Watkins), and culture (like Kathie Lee Gifford and actress Nancy Stafford). This percentage is not dramatically different from the percentage of women in Congress or the percentage of women who are corporate officers, but it is much lower than the percentage of women in the U.S. labor force and even those who fill MBA slots at top schools.

In other words, women in elite circles are still few and far between, but there are some important differences between women in general and women within the evangelical world. Gayle Miller is a good example. The former president of Anne Klein II, Miller spent her working lifetime in the world of retail fashion. When we met for her interview in Los Angeles, she spoke at length of the challenges she faced at the start of her career in the 1950s: “No one wanted to give us credit, no one wanted to sell us fabric. [The thinking was] ‘How can two dumb blondes make this on their own?”’ In the end, of course, she did make it, becoming head of the country’s market leader for professional women’s attire. During the course of her career, she turned away from her Mormon background and became a charismatic Christian through the Vineyard Church. Over the years, she has joined the boards of evangelical organizations, often serving as the lone female director. On several occasions, she encountered an evangelical bias against women, especially as she sought to recruit more women to boards or as speakers for various programs. She told me, “When I would say something like, ‘You know, women are very good organizers and speakers, and we also know how to talk to people of power,’ [the men] would just laugh.” Asked if evangelical women sense the exclusion at these various groups, she responded, “Sense it? They might as well have a sign out on the [door].” Several of the women I interviewed, like Miller, did not have children of their own, and they said that gave them more time for work. Among those with children, all said their husbands shared equally in family duties, something that is not true of most evangelicals or of most men in this country. In fact, many women executives said their husbands serve as primary caregivers for their children. Marjorie Dorr, president of Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, whose husband stayed home for seven years with their sons, told me, “You can’t do this without that [kind of support].” In similar fashion, Tami Heim’s husband stayed home to take care of their daughter and her aging mother — who was suffering from Alzheimer’s — while Heim traveled the globe as president of Borders. As she began to rise within the organization, Heim’s husband quit his job as a research scientist at Eli Lilly and became the family “anchor.”

As much as these women appreciate the egalitarian perspectives of their husbands, all of them talked about their family situation with a tinge of regret. Marjorie Dorr hates that she doesn’t get home until eight at night because it makes her feel like she is avoiding family responsibilities. Karen Hughes, counselor to President George W. Bush, shocked the political establishment when she resigned to spend more time with her teenage son. “I felt like I was … shirking my obligations as his mom,” Hughes told me when we met. “When I worked in the Texas governor’s office, I had a very busy job and a very big job. But … the White House is different … It’s pretty constant and frenetic. And it is hard to balance [work and family there] … I found … that I was torn all the time. I felt like I wasn’t really able to have time for my true priorities.” She returned to Washington in 2005 after her son went away to college.

The tension between professional obligations and family expectations, grueling for all women, seems especially so for evangelical women. Some observers, especially feminists — even evangelical feminists — were “mad,” Hughes said to me, when she left her powerful position in the Bush White House “because they thought that it … made it look as if women couldn’t get to the top without leaving it all for their family.” Hughes said her evangelical faith did not compel her return to Texas; if anything, she felt that it sustained her as she tried to balance work and family. Nevertheless, even though most of their own families do not exhibit the patriarchal tendencies typical of American evangelicalism, these leaders feel torn between family desires and professional ambition. From talking with many female leaders, it is obvious that the evangelical community does not support them enough in juggling these competing demands, a topic to which we will return later.

The vast majority of the evangelicals I interviewed are Protestant, and most are involved in some type of faith-based small group. They are not particularly loyal to a single congregation or even a single denomination. Almost three in five have switched congregations and denominations more than once, and the figure is even higher (80 percent) among younger leaders. Surprisingly, more than half of all leaders talked about embracing the evangelical approach to faith — ”deciding to follow Jesus,” in evangelical parlance — after high school. Evangelicalism’s most prolific pollster, George Barna, has found that “if people do not embrace Jesus Christ as their Savior before they reach their teenage years, the chance of their doing so at all is slim.” This suggests that American leaders’ spiritual journeys are noticeably different from those of the general population. Faith is important to them, but they often embrace it later in life.

What does the typical evangelical public leader look like? Meet William Inboden. Educated at Stanford before earning a PhD in history at Yale, Inboden is like many other leaders I interviewed. He held several influential positions before assuming his current role at the National Security Council and was a primary author of the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, legislation that reflected growing evangelical activism in foreign affairs. As Inboden has worked into the upper echelons of government, he has not jettisoned his evangelical convictions; in fact, he regards them as deeply enmeshed in his work. He told me, “My work and [professional] gifts are a stewardship from God to be used for his glory … [It requires] me to act with honor and integrity and to love those whom I work with as [ones] created in the image of God.” Like others I interviewed, Inboden embraces an irenic, ecumenical spirit that has emerged in recent years among Protestants and Catholics, and he believes there is an “imperative” that he share his faith with others. Inboden has also been involved with various networks of influential evangelicals, groups that have helped advance his own career. To support his studies at Yale, he received a Harvey Fellowship, which is a scholarship for talented evangelical graduate students. And while in Washington he has participated in evangelical groups like Faith and Law and Civitas. Inboden’s vision is shared by many I interviewed: an evangelical engagement with the political, intellectual, and cultural currents of the day in such a way that people of faith not only “follow the culture [but actually] shape it.” That, in brief, is a snapshot of evangelical leaders today and what they hope to accomplish from within the halls of power.

Since 1976, hundreds of evangelicals like Inboden have risen to positions of public influence. But they have not done so by chance. The rise of evangelicalism is the result of the efforts of a select group of leaders seeking to implement their vision of moral leadership. They have founded organizations, formed social networks, exercised what I call “convening power,” and drawn upon formal and informal positions of authority to advance the movement. Sociologist Randall Collins has argued that recognition and acclaim are bestowed upon leaders and ideas through structured, status oriented networks. Over the last three decades, the legitimacy that has come to the evangelical movement has come through the political, corporate, and cultural leaders who were willing to publicly associate with it. Evangelicalism, with its history of spanning denominational boundaries, is well suited to help evangelicals build connections with important leaders and prestigious institutions. They have formed alliances with diverse groups, giving the movement additional cachet and power in surprising ways. Leaders are often at the vanguard of a movement, and this book shows how evangelicals endowed with public responsibility have been at the forefront of social change over the last thirty years. By building networks of powerful people, they have introduced evangelicalism into the higher circles of American life. The moral leadership they practice certainly grows out of their evangelical convictions, but it also reflects the privileges they enjoy and the power they wield. Indeed, their leadership is an extension of — not a departure from — the elite social worlds they inhabit.

As I left the News Corp party that Rupert Murdoch threw back in 2004, I was handed a gift package with a note from Rick Warren inside. It read:

Thank you for honoring me with your presence this evening. No one is more amazed than I am with the Purpose Driven Life phenomenon. Who could have predicted it would make publishing history? It’s both astonishing and humbling. Because you are a leader that has expressed some interest in living with purpose, I’d like to invite you to be part of a very exclusive group. Each Thursday morning I lead an international study by conference call for influential leaders. It is a by invitation only group that has included some of the best known leaders in entertainment, business, politics, education, sports, media and the military. It is quite a mix of people, with the only common denominator being people of influence who have a desire to live with more purpose in their lives. If you are interested in listening in on one of these calls, just email [me] and I’ll send you the details.