new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: muriel spark, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: muriel spark in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

“I’ve never met a really good writer who lives in high style. I think a stylish life is unsuitable to the writer, and very often in the house where there’s a mild disorder one finds the writer with the best powers of organising his work. Order where order is due.”

Muriel Spark— “The Poet’s House”

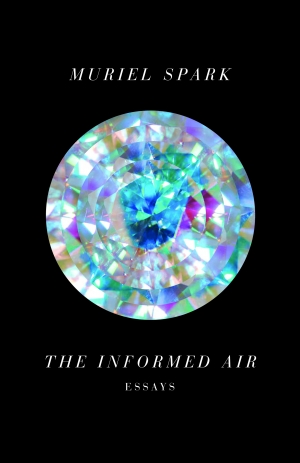

Read this and many other wonderful essays by Muriel Spark in The Informed Air, which will be released by newdirectionspublishing on April 29th.

(Source: kevinelliottchi, via maudnewton)

(I’m counting the days until this book comes out!)

She’ll perch on a stool and play with the wooden dolls on my shelves by the hour. This is how Sunday afternoon unfolds: her soft doll-chatter murmuring beside me while I’m reading, studying, or (as was the case this weekend) cleaning out closets.

I see Joanna Trollope’s Other People’s Children peeking out from one of the stacks; I read it on (I think it was) Lesley’s recommendation and found it wholly absorbing, thoughtful, vivid, a bit sad. I liked it very much. Those shelves are a jumble of things I’m eager to read but haven’t had a chance yet (Green Dolphin Street, borrowed from my friend Carmen; The Light Between Oceans, a gift from my publisher last Christmas; Brideshead Revisited, because I still—still! still!!1!!—haven’t, among others) and books I love so much I need to keep them close. (A Far Cry From Kensington; One Man’s Meat; Dear Genius; etc. etc. etc.)

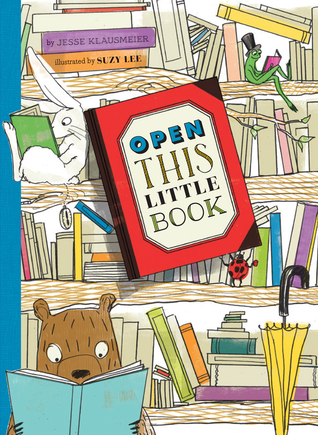

Notable picture-book reads of late: The Artist Who Painted a Blue Horse—a top-ten favorite of Rilla’s, and she’ll talk your ear off about the highlight colors in the paintings, if you like; Miss Suzy, back in frequent rotation; Open This Little Book, of which Huck cannot get enough; and to Huck for the very first time—oh! this particular milestone has been one of the most delightful I’ve experienced with each of the kids, one by one—Make Way for Ducklings. You can tell he’s the sixth child, not getting his full measure of McCloskey until the ancient age of four and a half. Scandal!

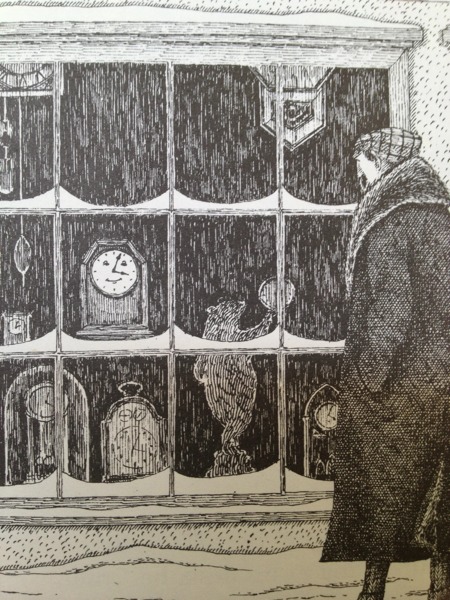

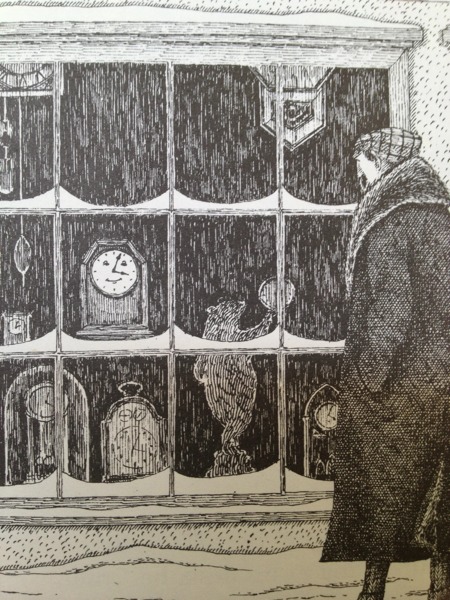

“To be perfectly honest, Ticky,” said Professor John, “I do not care for grandfather clocks as a rule. They are so very tall that one can never look into their faces and see what they are thinking. But your grandfather must be a very special clock, and it is always a good thing to have an ancestor who lives in a castle.”

—The Very Fine Clock by Muriel Spark, illustrated by Edward Gorey (1968)

On William, a highly intelligent medical student with an impoverished background:

“What moved and astonished me most was that he knew no nursery rhymes and fairy stories. He had read Dostoevsky, Proust, he read Aristotle and Sophocles in Gree. He had read Chaucer and Spenser. He was musical. He could analyse Shostakovich and Bartok. He quoted Schopenhauer. But he didn’t know Humpty Dumpty, Little Miss Muffet, the Three Bears, Red Riding-Hood. He knew the story of Cinderella only through Rossini’s opera. And all that sweet lyricism of our Anglo-Saxon childhood, a whole culture with rings on its fingers and bells on its toes, had been lost to him in that infancy of slums and smelly drains, rats and pawnshops, street prostitutes, curses, rags and hacking coughs, freezing bare feet and no Prince Charmings, which had still been the lot of the really poor in the years between the first and second world wars. I had never before realized how the very poor people of the cities had inevitably been deprived of their own simple folklore of childhood.”

On why writers should have cats:

“Alone with the cat in the room where you work, I explained, the cat will invariably get up on your desk and settle placidly under the desk-lamp…will settle down and be serene, with a serenity that passes all understanding. And the tranquillity of the cat will gradually come to affect you, sitting there at your desk, so that all the excitable qualities that impede your concentration and give your mind back the self-command it has lost. You need noto watch the cat all the time. Its presence alone is enough. The effect of a cat on your concentration is remarkable, very mysterious.”

“‘You are writing a letter to a friend,’ was the sort of thing I used to say. ‘And this is a dear and close friend, real—or better—invented in your mind like a fixation. Write privately, not publicly; without fear or timidity, right to the end of the letter, as if it was never going to be published, so that your true friend will read it over and over, and then want more enchanting letters from you. Now, you are not writing about the relationship between your friend and yourself; you take that for granted. You are only confiding an experience that you think only he will enjoy reading. What you have to say will come out more spontaneously and honestly than if you are thinking of numerous readers. Before starting the letter rehearse in your mind what you are going to tell; something interesting, your story. But don’t rehearse too much, the story will develop as you go along, especially if you write to a special friend, man or woman, to make them smile or laugh or cry, or anything you like so long as you know it will interest. Remember not to think of the reading public, it will put you off.”

—from A Far Cry from Kensington by Muriel Spark

I just wrote a long rambly dissertation on linksharing across various platforms, the pros and cons thereof, and then I decided it was too rambly even for me. So here’s a pretty picture instead.  These gorgeous blooms dazzled us at the outdoor mall today, where I took Huck and Rilla to get new shoes. We stopped for a bun at Panera and it’s possibly the first time I’ve ever been in a cafe with just those two; it was delightful, all chatter and energy, Rilla proudly cutting the bun in half and then carving her half into tiny bites, a frown of concentration, a very straight back. Toward the end an older couple got up from the next table and stopped to speak to us. “I’m usually quick to complain,” said the woman, rather ominously, “but—” and then lots of nice things about my children. Whew. The man was her “baby brother,” she told us, and it seems they quite enjoyed seeing miniature versions of themselves sharing a treat together.

These gorgeous blooms dazzled us at the outdoor mall today, where I took Huck and Rilla to get new shoes. We stopped for a bun at Panera and it’s possibly the first time I’ve ever been in a cafe with just those two; it was delightful, all chatter and energy, Rilla proudly cutting the bun in half and then carving her half into tiny bites, a frown of concentration, a very straight back. Toward the end an older couple got up from the next table and stopped to speak to us. “I’m usually quick to complain,” said the woman, rather ominously, “but—” and then lots of nice things about my children. Whew. The man was her “baby brother,” she told us, and it seems they quite enjoyed seeing miniature versions of themselves sharing a treat together.

Then we went to the shoe store, and Rilla hit her head on a shelf and the whole outing ended in tears. Which is pretty much how these things go. (She’s fine.)

Before the fall

The older girls got a book of Zelda sheet music for Christmas and have been learning the songs from their favorite Zelda iteration, Twilight Princess. I gave them the Lord of the Rings score as well because I want to hear those songs resounding through the house. This strategy is paying off quite nicely.

Reading notes: I finished Girls of Slender Means and have moved on to A Far Cry from Kensington, and the thing about Muriel Spark is that now that I’ve read her, she’s in my thoughts so constantly (this is the case ever since Memento Mori a couple of years ago) that I can hardly remember not having her voice among the influencers in my head. How did I, a reader, a book junkie, a student of literature, make it this long without Spark? How did I know how to look at streets and sentences without her? This is how she makes me feel. Her sentences are like the blades of ice skates, sharp, swift, carrying you along at some risk to your personal comfort. Sometimes Jane and I say to each other, can you imagine life without knowing Monty Python? Can you imagine living in the world without Holy Grail in the back of your mind? That’s how I feel about Muriel Spark. And I felt the same way last year after reading Elizabeth Goudge’s The Scent of Water. And before that, A. S. Byatt’s unbelievably rich (and dark) The Children’s Book, which I’ve read three times in as many years. Which realization sends a thrill up my spine: who else is out there waiting for me, waiting to change my world? Oh, writers of books, I adore you.

“The difficulty of getting rid of even one half of one’s possessions is considerable, even at removal prices. And after the standard items are disposed of—china, rugs, furniture, books—the surface is merely scratched: you open a closet door and there in the half-dark sit a catcher’s mitt and an old biology notebook.”

—E.B. White, “Removal,” One Man’s Meat

“…you should think of will-power as something that never exists in the present tense, only in the future and the past. At one moment you have decided to do or refrain from an action and the next moment you have already done or refrained; it is the only way to deal with will-power….I offer this advice without fee; it is included in the price of this book.”

—Mrs. Hutchins, the narrator of Muriel Spark’s A Far Cry from Kensington

Every Monday, Jen and Kellee at Teach Mentor Texts host a What Are You Reading? meme. Since there’s no question I like better, I’ll chime in.

Every Monday, Jen and Kellee at Teach Mentor Texts host a What Are You Reading? meme. Since there’s no question I like better, I’ll chime in.

Things we read around here today:

(To Rilla)

Peter and the Talking Shoes by Kate Banks, illustrated by Marc Rosenthal. I’ve enthused about this one before. One of my family’s longtime favorites. Peter has new (hand-me-down) shoes, whose rich life experience comes in handy when he has to fetch a series of necessary objects for local merchants: a feather to make the baker’s bread light, a key so the carpenter can unlock the door to the house she’s working on, and so on. It’s one of those delightful cumulative tales with a satisfying ending, and Marc Rosenthal’s art is priceless. We have mad love for this quirky book (now sadly out of print).

A Wonder Book for Girls & Boys by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Rilla knows the Greek myths pretty well (thanks to Jim Weiss and D’Aulaire), but it’s hard to beat Hawthorne’s elegant retelling.

(To Huck)

Inch and Roly and the Very Small Hiding Place. What can I say? He begged.

(Many times this past week, to all three of my youngest kids)

Open This Little Book by Jesse Klausmeier, illustrated by Suzy Lee. A series of quirky creatures is reading a series of little books, each smaller than the next. Very clever way to play with the convention of the codex. All those adorable nested books are irresistible to my kids. And the art, oh the art: utterly to swoon for.

(To me, at bedtime; at least, that’s the plan)

The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark. So far this is my favorite Spark yet. (I think the Monday meme is for children’s/YA titles only, but I can’t do a roundup without including my own current read.)

How about you?

Last month I sent Darin Strauss a copy of Muriel Spark’s Memento Mori after he vastly overpaid for his part of a cab ride home from a party. In return, he introduced me to the Essential Stories of V.S. Pritchett. And then he discovered an edition of Memento Mori with an introduction written by Pritchett (pictured), and we were as excited as any two book nerds could be.

So far I’ve only found a few tiny excerpts. “Only one other novelist and playwright of consequence — Samuel Beckett — had looked at Mrs. Spark’s subject: the corruption of the flesh, the tedium of waiting to die,” Pritchett said, praising her for taking on “the great suppressed and censored subject of contemporary society, the one we do not care to face, which we regard as indecent: old age.” I hope someone will get permission to republish the full text online.

Muriel Spark wrote a biography of Mary Shelley, Child of Light, that’s been out of print for years. Won’t someone revive it, as an ebook at least? This fan of both novelists would like to read it.

By: Maud Newton,

on 11/3/2010

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Culture,

Authors Speak,

memento mori,

muriel spark,

curriculum vitae,

barbara epler,

devaluation of comedy in literature,

girls of slender means,

prime of miss jean brodie,

Add a tag

My mystification that Muriel Spark isn’t more widely read has continued to grow, but last week her editor, New Directions publisher Barbara Epler, offered a theory in email that echoes what Howard Jacobson has said about the devaluation of comedy in literature.

“The fact that she is so unbelievably and witchily entertaining,” Epler argues, “has kept her from her full share of glory as the greatest British writer of the 20th century. Humor has never been the long suit of most critics.”

Spark really is hilarious, and her humor, like Twain’s, is the kind that doesn’t date. As my (new, thanks to Jessa) friend Elizabeth Bachner observed after I pressed Memento Mori on her as she headed to the train last week, she’s also incredibly sly.

Epler’s admiration was mutual. Spark praised her “wisdom, charm, humour and intuition, [which] must be the envy of every author.”

Reading Epler’s remarks on editing, it’s easy to see that she and Spark, who resisted all but the smartest and most intuitive edits, would have had a natural affinity. In 2008, Epler said, “Your job is just to worry, to check and double-check. One study pointed out that the difference between competent people and incompetent people is that competent people know they might be wrong and double- and triple-check; incompetent people know they’re right. (Or, as a Brazilian publisher joked, What’s the difference between ignorance and arrogance? “I don’t know and I don’t care.”) Editing doesn’t seem to be a process of knowing but of asking. You just do the best you can.”

And last year she spoke with Powell’s about, among other things, New Directions’ mission: “We really just try to find the best writing we can, albeit in a somewhat narrow bailiwick. (We are now owned by a trust and one of its provisions is that we continue to publish the kind of books J. L. wanted: a sort of baggy category, but with an emphasis still on experimental or what used to be called avant-garde writing.)”

New Directions has just republished Spark’s Not to Disturb, and will soon bring out her charming, idiosyncratic, stripped-down autobiography, Curriculum Vitae, which serves as a kind of preemptive corrective to Martin Stannard’s sprawling biography.

My personal Spark hierarchy starts like this: Memento Mori, T

By: Maud Newton,

on 10/6/2010

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

mark twain,

Ruminations on Writing,

Quotes & Excerpts,

eb white,

muriel spark,

tgbiw,

whingeing about novel writing,

absurdities of human existence,

one man's meat,

peter de vries,

Add a tag

Some writers shame and immobilize me with their brilliance, while others, like Twain, de Vries and Spark, dwarf my own efforts but inspire me to keep on.

Some writers shame and immobilize me with their brilliance, while others, like Twain, de Vries and Spark, dwarf my own efforts but inspire me to keep on.

It’s hard to pinpoint what separates the two groups; if pressed I’d say it’s an affinity of perspective — a morbid fixation on the absurdities of human existence — combined with precision, bluntness, and humor.

Of late, E.B. White has joined the second group. I’ve been making my way through One Man’s Meat — a collection of essays about leaving New York City for his Maine farm — and I particularly enjoyed this bit from an essay on his failed efforts to raise turkeys for money:

[T]here is nothing harder to estimate than a writer’s time, nothing harder to keep track of. There are moments — moments of sustained creation — when his time is fairly valuable; and there are hours and hours when a writer’s time isn’t worth the paper he is not writing anything on.

I’ve previously mentioned this great aside, in the same vein, from his Paris Review interview:

Delay is natural to a writer. He is like a surfer — he bides his time, waits for the perfect wave on which to ride in. Delay is instinctive for him. He waits for the surge (of emotion? of strength? of courage?) that will carry him along. I have no warm-up exercises, other than to take an occasional drink.

I guess the reason writers have to clear the decks is that they never know when the “moments of sustained creation” will come, and they have to be sitting in front of the page, waiting for them — and pushing through the others.

Which is to say (and to remind myself) that I’m still finishing my novel and, apart from the day job, doing very little else. Last week’s posting flare-up was an anomaly.

See (and hear) also: a 1942 interview with White on One Man’s Meat, rare recordings of the author reading from Charlotte’s Web and The Trumpet of the Swan, and his response to a fan who wanted to visit him at his farm: “Thank you for your note about the possibility of a visit. Figure it out. There’s only one of me and ten thousand of you. Please don’t come.”

By: Maud Newton,

on 6/15/2010

Blog:

Maud Newton

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

brad gooch,

elizabeth hardwick,

flannery oconnor,

paris review diary,

usage pedantry,

Personal,

kingsley amis,

Published Elsewhere,

muriel spark,

everyday drinking,

Add a tag

I can’t believe I forgot to link to the second installment of my Paris Review Daily Culture Diary.

I can’t believe I forgot to link to the second installment of my Paris Review Daily Culture Diary.

It’s not any sexier than the first, I’m afraid, but if you’re craving more usage pedantry, solo drinking tips, or line-editing blow-by-blows, you won’t want to let this one pass you by.

Here’s one of the mouse-over notes:

After reading Brad Gooch’s biography of Flannery O’Connor last year, I internalized her (and Elizabeth Hardwick’s) prohibition against allowing the same word to appear twice on a page, and my prose strains in places as a result. I wonder: did O’Connor read Muriel Spark? If so, confronted with such hilarious and inarguably brillliant repetitions — see, e.g., the sticks* — how could she have continued to adhere to her rule? Also how did Spark reuse words so imaginatively? She built humor through the sameness but somehow made the descriptions fresh every time. I wish she could revise this scene I’m getting ready to work on now, the one with the dogs in the car.

As predicted, Caitlin Roper’s issue of The Paris Review was waiting in my mailbox on my return from Florida. I turned first to my friend Victor LaValle’s essay, which is just great, and then to the R. Crumb interview, which you won’t want to miss if you’re a fan, and then, fingers quivering with anticipation, I read the Katherine Dunn story.

* Mouse-over note from the first installment: “By now there are passages I could almost quote from memory — especially the post-funeral scenes involving the writer with rheumatoid arthritis slouched over ‘two sticks,’ making his way among the funeral flowers as the other elderly characters goggle at him. The novelty of the Scottishism (’sticks’ rather than ‘canes’) tickles me, of course, but it’s the perfect, deadly repetition of the word — all the glimpses of the ‘clever little man doubled over his sticks’ — that makes this section so funny.”

Andrew Gallix offers the ideas of Alain Robbe-Grillet, whose nouveau roman inspired Simone de Beauvoir and Muriel Spark, among others, as a rejoinder to David Shields’ (reductive) Reality Hunger.

Muriel Spark’s 1992 autobiography has been characterized as purse-lipped, sterile, and withholding, a manipulative account designed to settle scores and divert attention from anything unflattering.

Curriculum Vitae may be more factual than confessional, but judged on its own terms rather than by the standards of the contemporary tell-all, the book is a charming, idiosyncratic, and closely observed personal history, one that manages to surprise even as it turns out to be almost exactly what you’d expect the author of Memento Mori, The Comforters, and A Far Cry from Kensington to offer up.

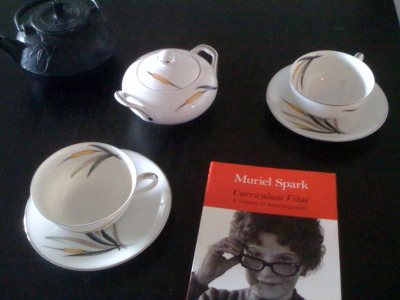

In an early passage, Spark explains the way children made tea in 1930s Edinburgh.

Sixty years ago is a short time in history. As recently as that I made at least one pot of tea for the family every day. It was delicious tea. Every schoolgirl, every schoolboy, knew how to make that exquisite pot of tea.

You boiled the kettle, and just before it came to the boil, you half-filled the teapot to warm it. When the kettle came to the boil, you kept it simmering while you threw out the water in the teapot and then put in a level spoonful of tea for each person and one for the pot. Up to four spoonfuls of tea from that sweetly odorous tea-caddy would make the perfect pot. The caddy spoon was a special shape, like a small silver shovel. You never took the kettle to the teapot; always the pot to the kettle, where you filled it, but never to the brim.

You let it stand, to ‘draw’, for three minutes.

The tea had to be drunk out of china, as thin at the rim as you could afford. Otherwise you lost the taste of the tea.

You put in milk sufficient to cloud the clear liquid, and sugar if you had a sweet tooth. Sugar or not was the only personal choice allowed.

Everyone who came to the house was offered a cup of tea, as in Dostoyevsky. What his method of making tea was I don’t know. (Tea from samovars must have been different, certainly without milk, and served in a glass set in a brass or silver holder.)

Tea at five o’clock was an occasion for visitors. One ate bread and butter first, graduating to cakes and biscuits. Five o’clock tea was something you ‘took’. If you had it as six you ‘ate’ your tea.

Tea at half-past six was high tea, a full meal which resembled breakfast. You had kippers, smoked haddock (smokies), ham, eggs or sausages for high tea. Potatoes did not accompany this meal. But a pot of tea, with bread, butter and jam, was always part of it.

In my continuing quest to set the world record for dullness, tonight I’m picking up some sausages on the way home and following Spark’s instructions with the pretty tea set (above) that Lizzie gave me for Christmas. Too bad I don’t have any darning to do. Afterward, naturally, I’ll go out on the balcony and water my plants.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie Muriel Spark

Miss Jean Brodie is a teacher at an Edinburgh day school in the 1930s and is best explained on page 62:

There were legions of her kind during the nineteen-thirties, women from the age of thirty and upward, who crowded their war-bereaved spinsterhood with voyages of discovery into new ideas and energetic practices in art of social welfare, education or religion. The progressive spinsters of Edinburgh did not teach in schools, especially in schools of traditional character like Marcia Blaine's School for Girls. It was in this that Miss Brodie was, as the rest of the staff spinsterhood put it, a trifle out of place... it goes on in for another three pages...

Miss Brodie is a woman in her prime, full of new and unconventional ideas, hemmed in by the conventional and conservative school. She admires Mussolini. She takes a lover. She has great passion for the arts. She is forever under suspicion from the headmistress who constantly looks for things to use against her. She takes five girls under her wing and they form the Brodie set, girls that she holds close all through their years at the school and that she attempts to mold in her own image. One of them will betray her.

What we get is a darkly (and subtly) funny character study of a woman who is convinced that she is in the prime of her life and invincible. The narration jumps all over the place in terms of time, but never in a confusing way. We know what the girls will do in bits and spurts and find out slowly how they get there. Spark reveals one piece of the mystery of the betrayal and one piece of each character as a whole, slowly building complete characters and plot into completion. Along the way, she explores loyalty and manipulation.

I initially wanted to read this because Jenny Davidson mentions it in the back matter of

The Explosionist (are we getting a sequel to that any time soon?!), and then it appeared on the list of 1001 Novels to Read before you Die and the Guardian's list of 1000 Novels to Read Before You Die.

It's a wonderful story with hidden depth. I've been puzzling over it and thinking over it for quite some time before I was able to write this review. It seems rather basic (although the unlinear narration was a novelty at the time of publication) but the depth of the character study, and not just for Miss Brodie, but for many of the girls in her set, comes out upon further reflection.

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

Every Monday, Jen and Kellee at

Every Monday, Jen and Kellee at

Some writers shame and immobilize me with their brilliance, while others, like

Some writers shame and immobilize me with their brilliance, while others, like  I can’t believe I forgot to link to the second installment of my

I can’t believe I forgot to link to the second installment of my

and may I recommend the movie! It's very well done. :)

I'm glad to hear it! Also, Dame Maggie Smith! Who doesn't love her? I must add it to my Netflix queue.

EXPLOSIONIST sequel is INVISIBLE THINGS, I am just finalizing copy-edited manuscript and it will be out in fall 2010 - glad you liked the Spark novel!

Huzzah! I can't wait for it! Thanks for letting us now, and thanks for planting the name of this in my brain, so that it caught my eye on other lists!