Alexius Meinong (1853-1920) was an Austrian psychologist and systematic philosopher working in Graz around the turn of the 20th century. Part of his work was to put forward a sophisticated analysis of the content of thought. A notable aspect of this was as follows. If you are thinking of the Taj Mahal, you are thinking of something, and that something exists.

The post The strange case of the missing non-existent objects appeared first on OUPblog.

The traditional view puts forward the idea that the vast majority of what there is in the universe is mindless. Panpsychism however claims that mental features are ubiquitous in the cosmos.

The post Is the mind just an accident of the universe? appeared first on OUPblog.

Planet Earth doesn’t have ‘a temperature’, one figure that says it all. There are oceans, landmasses, ice, the atmosphere, day and night, and seasons. Also, the temperature of Earth never gets to equilibrium: just as it’s starting to warm up on the sunny-side, the sun gets ‘turned off’; and just as it’s starting to cool down on the night-side, the sun gets ‘turned on’.

The post Climate change – a very difficult, very simple idea appeared first on OUPblog.

In early May 1913 Bertrand Russell sat down to write a book on the theory of knowledge, his first major philosophical work after Principia Mathematica. He set a brisk pace for himself – ten pages a day at first, up to twelve by mid-May. He was “bursting with work” and “felt happy as king”. By early June he had 350 pages. 350 pages in one month!He never finished the manuscript. Some parts of it were published as journal articles, but the book itself was never completed. (It was later published posthumously under the title Theory of Knowledge.) What went wrong?

The post What made Russell feel ready for suicide? appeared first on OUPblog.

By Marjorie Senechal

It was eerie, a gift from the grave. But I thank serendipity, not spooks. The gift, it turns out, was given forty years ago. When Dorothy Wrinch cleared out her office in the Smith College Science Center, she left her books for the library, her burgeoning notebooks and contentious correspondence for the archives, and three boxes of crystal models and model parts for me. But I was on sabbatical, and whoever stashed the boxes in the basement never told me. They’d be there still had a young colleague not gone rummaging for something else last fall and found them, “For Mrs. Senechal” pencilled on the top. And so they reached me at last. Forty years ago, I would have treasured these models as she had. But what can I do with them now?

Bring them to Montreal for show-and-tell? Crystallographers from all over the world are gathering there for their triennial Congress. The year 2014 is a special anniversary. On the eve World War I, an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, William Lawrence Bragg, walking along the river behind his college, found the Rosetta Stone of the solid state. The then-recent discovery that crystals scatter x-rays had solved for the x: the mysterious rays are waves, like light. Bragg turned this around, deciphering the structures of simple crystals from the patterns in their scattered rays. Today’s textbooks trace the path from his work on table salt and diamond to the double helix, modern drug design, and the highest of high-tech materials. We forget that the path was neither easy nor straight. The boxes of chipped and scattered model parts Wrinch left me bear witness to the early years, when scientists argued over whether salt is really the 3-D atomic checkerboard Bragg said it was, whether proteins are chains or rings as Wrinch said they were, and how to interpret the diffraction patterns of mind-bogglingly complicated crystals.

But the boxes are bulky and too heavy for airlines that charge by the ounce. So what should I do with them? I’m deeply touched by the gift; I won’t throw them out. But if they were ever user-friendly, they aren’t anymore. It’s hard to fit the rods into the balls, and the paint on the balls is flaking. And who needs real models now, when we have vivid, interactive computer graphics on our iPads? (Let’s get that one out of the way: real models are still working tools for me and I’m not alone.) No, it’s not their aged parts, it’s their aged ideas that make these models obsolete.

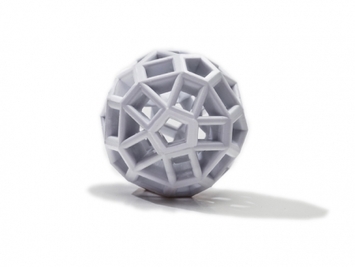

Figure 1. A ball from the box of model parts that Dorothy Wrinch left for me.

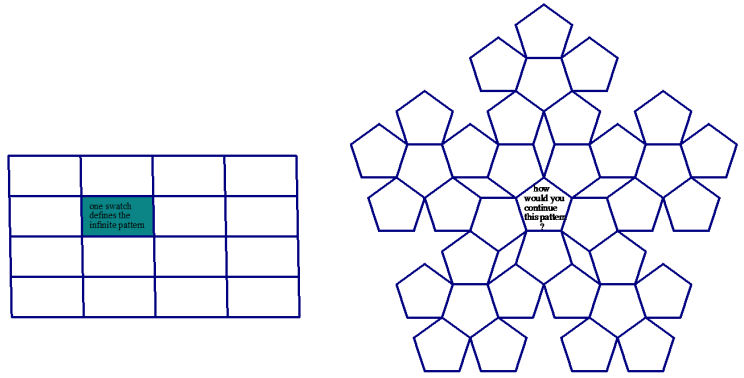

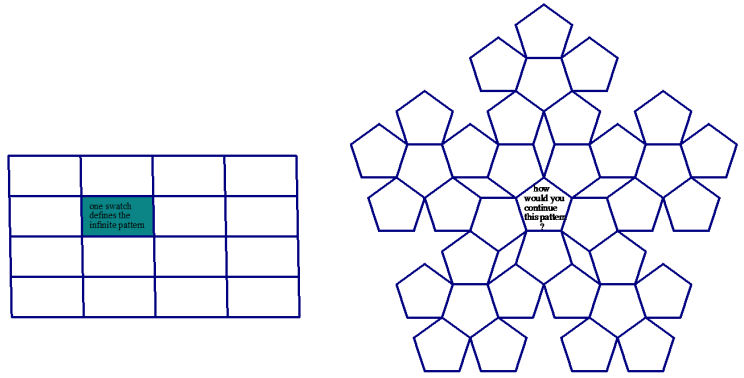

One book Wrinch didn’t leave for the library was a massive, gilded tome called Grammar of Ornament. It’s a cornerstone of the decorative arts, a veritable catalogue of rectangular swatches of floor, wall, and ceiling patterns created by people in all times and places. She loved this book because ornaments are like 2-D crystals. This analogy was crystallography’s chief paradigm, questioned by no one: the atoms in crystals repeat periodically in space. If you know one swatch (crystallographers call it a unit cell), you know the whole thing. A Grammar of Crystals would be a catalogue of swatches of 3-D atomic patterns. But that was then. Swatches are to modern crystallography as Pythagoras’s whole-number ratios are to √2 and pi. They’re still useful, but they’re not the whole story. The world of crystals, like the world of numbers, turns out to be bigger than anyone imagined.

Look closely at Wrinch’s wooden balls (Figure 1). The holes are drilled at the corners of squares, and at the centers of those squares, and at the centers of their edges. Six squares make a cube; if you picked up a ball and turned it around, you’d see the cubic pattern. With balls like these and rods to connect them, you can build 3-D swatches that stack like bricks to fill space. And that’s all you can build. But as the last century drew to a close, this paradigm crumbled. There are crystals, we now know, whose atomic patterns don’t repeat like ornaments. They spring surprises at every turn (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Left: To create this pattern, just fit the swatches together. Right: How would you extend this swatchless pattern?

Aperiodic crystals have opened a new chapter; what will its paradigms be? At this still-early stage, we conjecture, argue, explore the new terrain from every angle. It’s fitting, and telling, that the Montreal Congress will be a double celebration. If ever a scientific discovery changed the world, x-ray crystallography did. But, paradoxically, the Congress will give its plums and prizes this year to the scientists who consigned its paradigm to history’s basement and sent us back to basics.

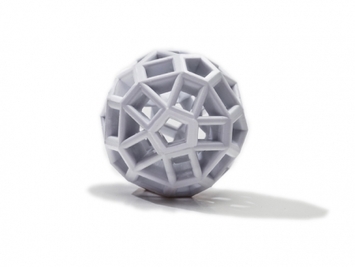

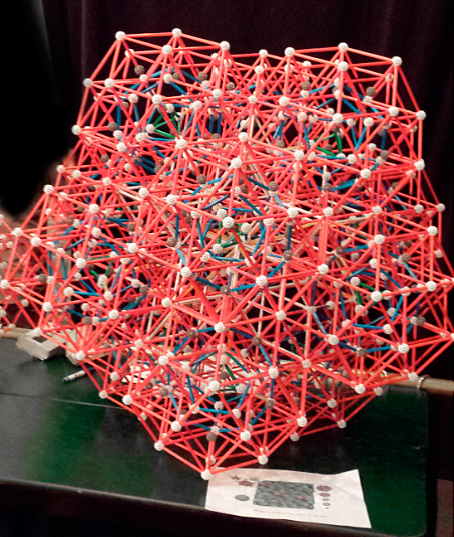

Figure 3. Compare the flexibility of this modern Zome Tool connector with its rigid ancestor in Figure 1.

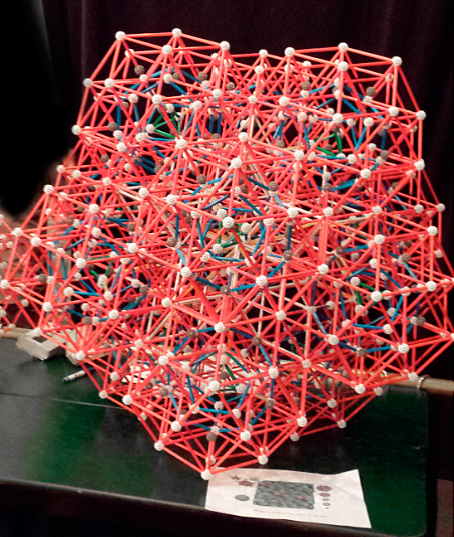

Figure 4. A model of an actual non-repeating crystal structure made with Zome Tools by my students at the Park City Mathematics Institute, July 2014. Though aperiodic, this pattern of atoms can be extended in space.

I’ll put Wrinch’s models back in storage. She wouldn’t mind. “A science which hesitates to forget its founders is lost,” Alfred North Whitehead declared in 1916. A mature science, he explained, reconfigures itself as a logical structure from which the arguments and passions that built it are erased. Dorothy, then a student of his colleague Bertrand Russell, took the logical structure of science as a challenge. Later, when she ventured into less abstract realms, their reconfiguration was her mission. She would be delighted, I think, that so much of crystallography is automated today, and that the Grammar of Crystals is a databank. She would be delighted by new vistas to be reconfigured with modern models. And she would be delighted that crystallographers are still arguing.

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, and Co-Editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer. She is author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science. She will be attending the International Union Of Crystallography Congress in Montreal 5-12 August 2014.

Chemistry Giveaway! In time for the 2014 American Chemical Society fall meeting and in honor of the publication of The Oxford Handbook of Food Fermentations, edited by Charles W. Bamforth and Robert E. Ward, Oxford University Press is running a paired giveaway with this new handbook and Charles Bamforth’s other must-read book, the third edition of Beer. The sweepstakes ends on Thursday, August 14th at 5:30 p.m. EST.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Photos by Marjorie Senechal.

The post Boxes and paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

“The Catholic Church was derived from three sources. Its sacred history was Jewish, its theology was Greek, its government and canon law were, at least indirectly, Roman… In Catholic doctrine, divine revelation did not end with the scriptures, but continued from age to age through the medium of the Church, to which, therefore, it was the duty of the individual to submit his private opinions. Protestants, on the contrary, rejected the Church as a vehicle of revelation; truth was to be sought only in the Bible, which each man could interpret for himself. If men differed in their interpretation, there was no divinely appointed authority to decide the dispute. In practice, the State claimed the right that had formerly belonged to the Church, but this was a usurpation. In Protestant theory, there should be no earthly intermediary between the soul and God.

The effects of this change were momentous. Truth was no longer to be ascertained by consulting authority, but by inward meditation. There was a tendency, quickly developed, toward anarchism in politics, and, in religion, toward mysticism, which had always fitted with difficulty into the framework of Catholic orthodoxy. There came to be not one Protestantism, but a multitude of sects; not one philosophy opposed to scholasticism, but as many as there were philosophers; not, as in the thirteenth century, one Emperor opposed to the Pope, but a large number of heretical kings. The result, as thought in literature, was a continually deepening subjectivism, operating at first as a wholesome liberation from spiritual slavery, but advancing steadily toward a personal isolation inimical to social sanity.

Modern philosophy begins with Descartes, whose fundamental certainty is the existence of himself and his thoughts, from which the external world is to be inferred. This was only the first stage in a development, through Berkeley and Kant, to Fichte, for whom everything is only an emanation of the ego. This was insanity, and, from this extreme, philosophy has been attempting, ever since, to escape into the world of everyday common sense.”

– Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy