By Kandice Rawlings

Leonardo da Vinci was born 562 years ago today, and we’re still fascinated with his life and work. It’s no real mystery why – he was an extraordinary person, a genius and a celebrity in his own lifetime. He left behind some remarkable artifacts in the form of paintings and writings and drawings on all manner of subjects. But there’s much about Leonardo we don’t know, making him susceptible to a number myths, theories, and entertaining but inaccurate representations in popular culture. The following are some of my favorites.

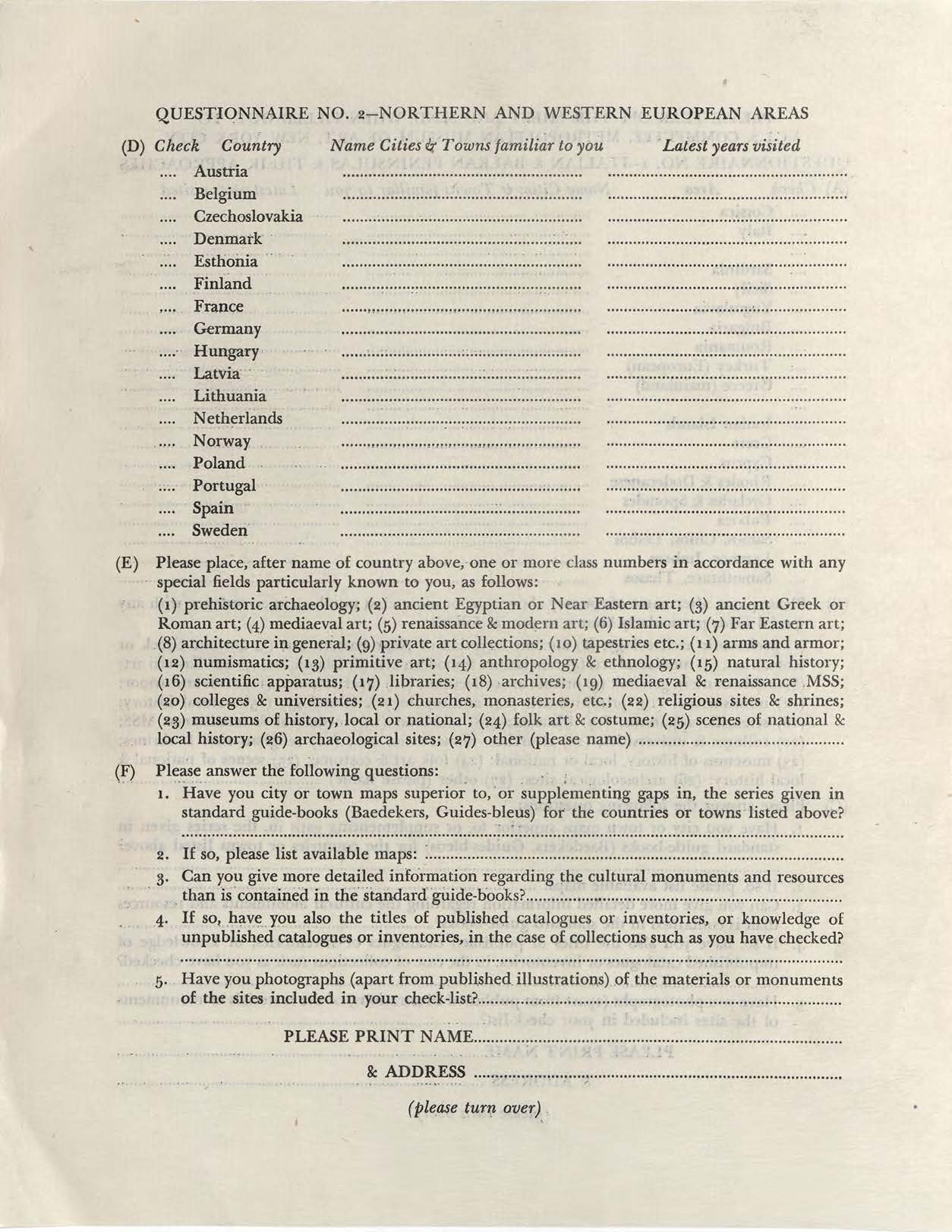

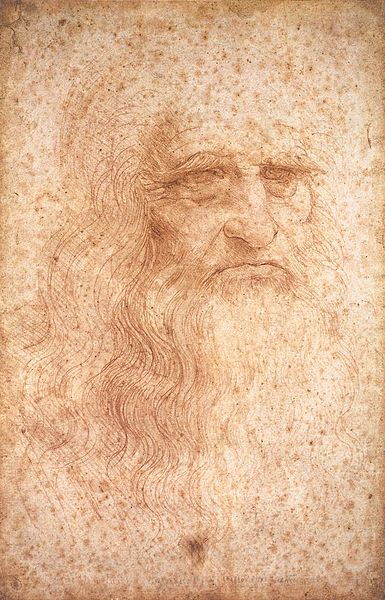

Leonardo da Vinci, Presumed Self Portrait, circa 1512. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #1 – Leonardo was gay.

Leonardo’s possible homosexuality is one of the more prevalent – and more plausible – myths circulating about the artist, and has the backing of none other than Sigmund Freud. There’s no way of knowing Leonardo’s sexual orientation for sure, but he isn’t known to have had romantic relationships with any women, never married, and in 1476 was accused (but later cleared) of charges of sodomy – then a capital crime in Florence. Scholars’ opinions on the issue fall along a spectrum between “maybe” and “very probably”.

Conclusion: Maybe true.

Myth #2 – Leonardo wrote backward to keep his ideas secret, and his notebooks weren’t “decoded” until long after his death.

For all his skill, Leonardo was not a prolific painter – the major part of his surviving output is in the form of his notebooks filled with theoretical and scientific writings, notes, and drawings. His strange habit of writing backward in these notebooks has been used to perpetuate the image of the artist as a mysterious, secretive person. But in fact it’s much more likely that Leonardo wrote this way simply because he was left-handed, and found it easier to write across the page from right to left and in reverse. No decoding is necessary – just a mirror. Leonardo’s theoretical writings and other notes were preserved by his follower and heir Francesco Melzi, and were widely known, at least in artistic circles, during the 16th and 17th centuries. Published extracts began appearing in 1651.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #3 – Leonardo put “secret” codes and symbols in his works.

I’d rather not get into all the problems with The Da Vinci Code too much, but I have to credit this 2003 book, by renowned author Dan Brown, for a lot of these theories. Aside from the fact that the book is full of factual errors (example: Leonardo’s “hundreds of Vatican commissions,” which actually number in the vicinity of zero) and twists the historical record, its readings of Leonardo’s artworks are based on some fundamentally flawed conceptions about the making, meaning, and purpose of art in the Italian Renaissance. In Leonardo’s world, paintings like the Last Supper in Milan were made according to patrons’ requirements, with very specific Christian meanings to be conveyed. Despite Leonardo’s artistic innovations, the content of his religious paintings and portrayal of religious figures (with the exception of some details in an altarpiece from the 1480s) were not untraditional.

Conclusion: False.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, between 1503-1505. Louvre. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #4 – The Mona Lisa is a self-portrait/male lover in disguise/woman with high cholesterol.

Martin Kemp has observed, “The silly season for the Mona Lisa never closes.” The ridiculous theories about this painting abound. Here’s what we can say with reasonable certainty: Leonardo started the painting, probably a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, a merchant’s wife, while in Florence around 1503. For unknown reasons, he didn’t deliver it to the patron, however, and it ended up in the possession of his workshop assistant Salai (who some think was Leonardo’s lover – again, without evidence). There’s no reason to think that Leonardo recorded in this painting his own features or those of Salai, even if, as many art historians believe, he continued to work on the painting after he left Florence for Milan and then France. In a theory that deviates from the usual speculation about the identity of the sitter, an Italian scientist thinks that the way Leonardo portrayed the sitter shows she had high cholesterol. Right, because Renaissance paintings are straightforward, scientific images, pretty much just like MRIs and X-rays.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #5 – Leonardo made the image of Christ on the Shroud of Turin.

The Shroud of Turin is a relic purported to be the shroud that Christ’s body was buried in after the Crucifixion. According to its legend, the image of his body was miraculously transferred to the cloth when he was resurrected. The idea that Leonardo forged it depends on claims that the proportions of Christ’s face as depicted on the shroud match those in a drawing that is thought to be a self-portrait by the artist, and that Leonardo devised a photographic process that transferred the image of his face to the shroud. The fact that the shroud dates to at least the mid-14th century, a hundred years before Leonardo’s birth, just makes this already kooky theory even harder to buy. I’ll admit, though, that I haven’t read the whole book explaining it … and I’m not going to.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #6 – Leonardo was a vegetarian.

Vegetarianism would have been pretty unthinkable in Renaissance Italy (and veganism just plain absurd); people probably ate about as much meat as they could afford. The most commonly cited quote used to back up this claim is taken from a novel (see p. 227) and often misattributed to Leonardo himself. None of Leonardo’s own writings or early biographies mentions any unconventional eating habits. There’s really only one documentary source that might be relevant, a letter written by a possible acquaintance of the artist, who compares Leonardo to people in India who don’t eat meat or allow others to harm living things. Pretty tenuous, but vegetarians love to claim him.

Conclusion: Probably false.

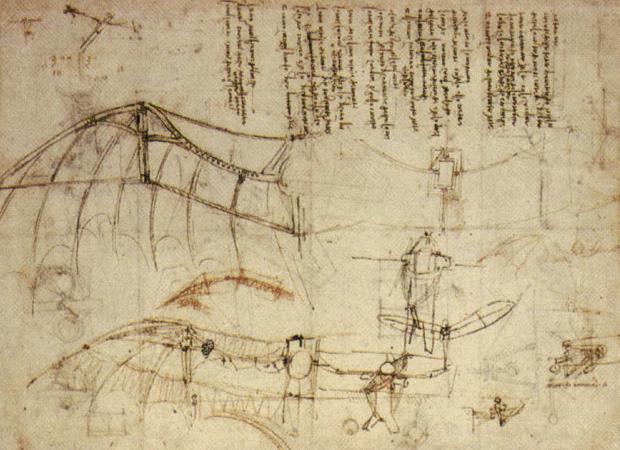

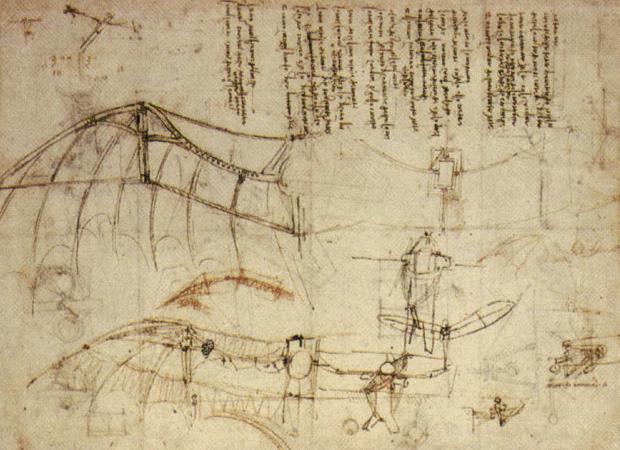

Myth #7 – Leonardo invented bicycles, helicopters, submarines, and parachutes.

It’s true that Leonardo was fascinated with mechanics, aerodynamics, hydrodynamics, flight, and military engineering, which he touted in his famous letter to Ludovico Sforza seeking a position at the court of Milan. Leonardo’s notebooks contain many designs for machines and devices related to these explorations. But these were, for the most part, probably not ideas that Leonardo considered thoroughly enough to actually build and demonstrate. In the case of the bicycle, the drawing was likely made by someone else, and might even be a modern forgery.

Conclusion: Not so much.

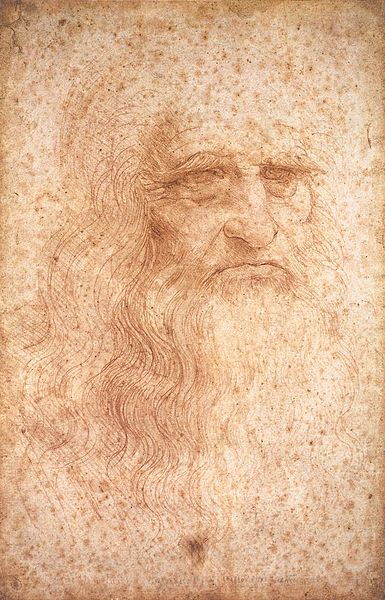

Leonardo da Vinci, Design for a Flying Machine, 1488. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #8 – Leonardo built robots.

While it sounds nutty, this one’s not so far off the mark, if you consider automatons – mechanical devices that seem to move on their own – to be robots. In a plot line of the cable fantasy drama Da Vinci’s Demons, Leonardo constructs a flying mechanical bird to dazzle the crowds gathered in the Cathedral piazza for Easter. A reliable historical record instead points to a lion that Leonardo made for the King of France’s triumphal entry into Milan in 1509. One observer’s description reads:

When the King entered Milan, besides the other entertainments, Lionardo da Vinci, the famous painter and our Florentine, devised the following intervention: he represented a lion above the gate, which, lying down, got onto its feet when the King came in, and with its paw opened up its chest and pulled out blue balls full of gold lilies, which he threw and strewed about on the ground. Afterwards he pulled out his heart and, pressing it, more gold lilies came out … Stopping beside this spectacle, [the King] liked it and took much pleasure in it.

Wow.

Conclusion: True.

If you’re interested in learning more about Leonardo, including the current locations of his works, read his biography from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, or, for a longer treatment, pick up the accessible but smart book by leading expert Martin Kemp.

Kandice Rawlings is Associate Editor of Oxford Art Online and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists. She holds a PhD in art history from Rutgers University.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Leonardo da Vinci myths, explained appeared first on OUPblog.

In celebration of World Art Day and Leonardo da Vinci’s birthday, we invite you to read the biography of da Vinci as it is presented in the Benezit Dictionary of Artists.

Italian, 15th – 16th century, male.

Active from 1515 in France.

Born 15 April 1452, in Anchiano, near Vinci; died 2 May 1519, in Clos-Lucé, near Amboise, France.

Painter, sculptor, draughtsman, architect, engineer. Religious subjects, mythological subjects, portraits, topographic subjects, anatomical studies.

Leonardo da Vinci was the illegitimate son of the Florentine notary Ser Piero da Vinci, who married Albiera di Giovanni Amadori, the daughter of a patrician family, in the year Leonardo was born. Little is known about the artist’s natural mother, Caterina, other than that five years after Leonardo’s birth she married an artisan from Vinci named Chartabriga di Piero del Veccha. Leonardo was raised in his father’s home in Vinci by his paternal grandfather, Ser Antonio. Giorgio Vasari discusses Leonardo’s childhood at length, noting his aptitude for drawing and his taste for natural history and mathematics. Probably around 1470, Leonardo’s father apprenticed him to Andrea del Verrocchio; two years later,Leonardo’s name appears in the register of Florentine painters. Although officially a painter in his own right, Leonardo remained for a further five years or so in Verrocchio’s workshop, where Lorenzo di Credi and Pietro Perugino numbered among his fellow students.

In 1482, Leonardo went to Milan to work in the court of Duke Ludovico Sforza and remained there until 1499, returning to Florence after brief visits to Venice and Mantua. During his second Florentine period, Leonardo gained notoriety, primarily as the result of two cartoons he worked up and put on public display. In 1508, Leonardo returned to Milan to work for the French rulers there and complete an altarpiece commission he had begun during an earlier stay. The artist made his first trip to Rome in 1513 and was involved there with military projects for Giuliano de’ Medici (the duke of Nemours and brother of Pope Leo X). Through the pope, Leonardo may have met the French king Francis I, who was Leonardo’s patron in the last few years of his life. The artist died near Amboise and was buried there, in the church of St Florentin. Because of these circumstances, several of Leonardo’s most treasured works, including the Mona Lisa, ended up in the French royal collection and are now preserved in the Louvre.

A few works can be attributed to the period of Leonardo’s training with Verrocchio: a landscape drawing dated 1473 and part of Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ (both Uffizi Gallery), namely the angel at the far left of the composition. In January 1478, now an independent painter, he was commissioned by the city of Florence to paint an altarpiece for the S Bernardo Chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio, which he did not complete. The following year, Leonardo made a drawing of the hanged body of an assassin involved in the Pazzi Conspiracy to overthrow the Medici government, which may have been connected with another state commission. In March 1480, he was retained to paint an altarpiece for the main altar in the monastery of S Donato a Scopeto, most likely the unfinished Adoration of the Magi, a dynamic reimagining of the subject. It appears that around this time he also produced numerous Madonna studies and his Portrait of Ginevra dei Benci, the first of his many captivating portraits of women.

In 1481, Leonardo wrote a letter to the new ruler of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, asking for a position at court. It is almost entirely devoted to his knowledge of military engineering and ideas for new weapons; the last paragraph briefly mentions that he is an able painter and can also assist in the completion of an equestrian monument of Ludovico’s father, Francesco, which had been planned but not begun. Leonardo arrived in Milan by 1483, perhaps with Medici assistance, and was contracted to paint an image of the Virgin for an altarpiece for the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception’s chapel in S Francesco Grande. This commission resulted in a protracted legal battle and two versions of the painting, the so-called Virgin of the Rocks; the first version, painted between 1483 and 1486, is in the Louvre, and the second, painted primarily in the 1490s, is in the National Gallery, London. The history of the two paintings and the authorship of the later version are much disputed.

During this period, Leonardo received commissions across a wide spectrum. He built stage equipment and devices used for the marriage ceremony of Gian Galeazzo Sforza; he travelled to Padua to supervise construction of the cathedral; he designed costumes for the festivities arranged to celebrate the marriage of Ludovico Sforza to Beatrice d’Este; and he drew a design for the crossing tower of the Milan Cathedral (1487). He made two portraits of women supposed to be Ludovico’s mistresses, Cecilia Gallerani (or Lady with an Ermine) and Lucrezia Crivelli (or La Belle Ferronnière).

Around 1495, Leonardo set to work planning decorations for the Castello Sforzesco. At the start of 1496, Leonardo and Ludovico, by that time the duke of Milan, quarrelled, and the duke repeatedly tried to entice Pietro Perugino as a replacement for Leonardo. Some two years later, the duke andLeonardo reconciled, and Leonardo started working again on the ducal palace and supervising fresco decorations for the Sala delle Asse. While out of favour with the duke, Leonardo had occupied himself with painting a monumental fresco of the Last Supper for the refectory of the Milan monastery of S Maria delle Grazie. In his life of Leonardo, Vasari asserts that execution of this fresco was fraught with difficulty. Leonardo’s use of an experimental medium in order to achieve the naturalistic effects of oil painting caused the fresco to deteriorate rapidly, with much of the original composition quickly being lost. By 1545, it was reported to have already been partially destroyed; three centuries later it was evident that years of neglect, humidity, and inept restorations (attempts at complete restoration were recorded in 1726 and 1770) had only served to make matters worse. A further and more successful attempt at restoration was undertaken in the early years of the 20th century, and the spirit of the original was recaptured, at least partially. The most recent restoration, begun in 1979, was completed in 1999. Fortunately, the original appearance of the Last Supper survives in the form of excellent copies made by students of Leonardo, possibly under his supervision. Among these is a copy reproducing the dimensions of the original (15 by 28 feet [4.5 by 8.60 metres]), painted around 1510 by Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli for the Carthusian church in Pavia and now in London’s Royal Academy. Another detailed reproduction was made by Marco d’Oggiono, commissioned by Connétable de Montmorency for the chapel at the castle of Écouen and now in the Louvre. Despite the fresco’s condition problems, it is one of Leonardo’s best-known and most influential works. The painting is admired for the variety of expressions and poses, the mastery with which Leonardocaptured the most dramatic moment of the biblical story, and the mathematical clarity and regularity of the space, which is conceived as an extension of the refectory (dining hall) it decorates.

Although in 1483 Leonardo had made a clay model of an equestrian sculpture of Francesco Sforza that was erected for the wedding celebrations of Bianca Maria Sforza and Emperor Maximilian, he did not begin work in earnest on the bronze Sforza monument until the 1490s. In fact, Ludovico wrote in a 1489 letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici that he feared Leonardo would not be able to cast the sculpture and requested Lorenzo to provide him with expert bronze sculptors as replacements. Although no finished sculptures by Leonardo have been identified, his training in Verrocchio’s workshop meant he would have received some degree of instruction on techniques of bronze casting; during the 1470s and 1480s, Verrocchio was occupied with various projects in bronze, including an equestrian monument in Venice. Later, during a stay in Florence in 1506–1507, Leonardo may have been involved the design of Giovanni Francesco Rustici’s bronze group St John the Baptist Preaching for the exterior of the Florence Baptistery. In any case, the Sforza monument was never cast, and the largest clay model that Leonardo completed suffered serious damage when French troops entered Milan in September 1499 and archers elected to use it for target practice. However, many drawings, both studies for the composition and technical designs for the casting, survive. The monument, if completed, would no doubt have been a major achievement, both artistically and technically.Leonardo planned a dynamic and highly innovative composition with a rearing horse and a fallen enemy beneath its forelegs, and the statue was to be colossal in scale. The project was abandoned when Leonardo fled the French invasion.

In December 1499, Leonardo went to Mantua with the mathematician Fra Luca Pacioli. There,Leonardo produced a highly finished drawing for a portrait of Isabella d’Este that was either never executed or has been lost. He then spent a short time in Venice before returning to Florence in April 1500. That same month, he finished a cartoon for a major work entitled Virgin and Child with St Anneand displayed it to adoring crowds at SS Annunziata. The cartoon is untraced but is thought the have been related to a drawing now in the National Gallery, London, and a painting of the same subject now in the Louvre. It was around this period (1500-1503) that Leonardo also began painting the portrait of Mona Lisa (or La Gioconda), generally believed to have been the wife of the Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo. According to Vasari, Leonardo worked on the Mona Lisa for the better part of four years, but he never delivered it to its patron, bringing it with him to France and perhaps working on it intermittently into his late years. He also made studies for Leda and the Swanthat were copied by his students and Raphael; the final painting is untraced and may have been finished much later, during Leonardo’s sojourn in Rome.

The end of 1502 saw Leonardo inspecting fortifications in the Romagna in his new capacity as senior military architect and general engineer in the service of Cesare Borgia. He was abruptly removed from this post in October of the same year when a rebellion broke out in the duchy. April 1503 foundLeonardo back in Florence and, in July of that year, the Republic of Florence dispatched him to an encampment near Pisa to conduct a survey on how the Arno River could be diverted behind Pisa (so that the city, then under siege by Florence, could be deprived of access to the sea). Later that year, in October, he embarked on a major decorative composition for the new Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the Five Hundred) in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The chosen theme was the victory of Florence over Milan at the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. This monumental work, like its intended complementary painting by Michelangelo of the Battle of Cascina, remained unfinished. Leonardowas commissioned to paint the mural in 1502 and was working on the fresco by 1504. Once again, technical problems frustrated him, notably the poor state of the wall surface he painted and again another experimental technique using oils, and he abandoned the project in 1506. Both the cartoon and the mural were avidly studied by younger artists and some of its appearance can be surmised from drawn and engraved studies. In 1563, Vasari covered the ruinous painting with a new fresco. A project to discover Leonardo’s painting beneath the later fresco using infrared and laser technology was launched in 2005, in the hopes that Vasari preserved it by leaving a gap between the Battle of Anghiari and the plaster for his own fresco.

Leonardo then spent a short time in Milan, perhaps to settle his long-standing commission for theVirgin of the Rocks, before returning to Florence, where he painted a Virgin and Child commissioned by a secretary of the French king Louis XII. At the insistence of Chaumont, the French governor of Milan, Leonardo returned to the Lombard capital and remained there until 1507, when he was obliged to return to Florence to assert his rights of inheritance under the terms of an uncle’s will. During this time, he painted two Madonnas that he took with him on his return to Milan. Leonardo was still in Milan when Louis XII arrived in that city after his victory at Agnadello. Based on a manuscript sketch, he probably also painted around this time the St John the Baptist now in the Louvre. Not least, he is believed to have painted around this date (and possibly in collaboration with one of his pupils) theVirgin and Child with St Anne, also in the Louvre. His preparatory sketches for the work strongly suggest that his initial intention was to paint an intimate ‘family portrait’, but that he subsequently elected for a composition that became widely acclaimed for the innovative contrapposto technique whereby Leonardo twisted a figure on its own axis, with a movement to the left counterbalanced by an equal and opposite movement to the right. The result is a pleasing dynamic symmetry.

During this period, Leonardo also began designing another equestrian monument, this one to commemorate Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, the governor of Milan under the French. When the Sforza returned to power, the project was abandoned. Leonardo remained in Milan after the withdrawal of the French in 1512 and it has often been speculated that Massimiliano Sforza may have been displeased and bitter at Leonardo’s decision to work there for the French occupiers. Whether that was the case,Leonardo recorded in his journal on 24 September 1513 that he was about to leave for Rome in the company of his pupils Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Francesco Melzi, Lorenzo, and Il Fanoia. In Rome, he was made very welcome by Pope Leo X and duly housed in the Belvedere. Demand for his services proved slight, however, and his output during this period seems inconsiderable. He may have worked there on his Leda and the Swan, together with a Madonna and Child and a Portrait of a Young Boy. There was also a rumour that his preoccupation with scientific studies, notably anatomy, did not endear him to the pontiff.

July 1515 saw Leonardo in the train of the papal army commanded by Giulio de’ Medici, and there are indications that he travelled with the army as far as Piacenza and that he was in Bologna in December 1515 for the signing of the concordat between the pope and Francis I of France. Shortly afterwards, Leonardo’s services as ‘first painter, architect and mechanic of the King’ were retained by Francis I in exchange for a pension amounting to 700 gold crowns and a private residence at Clos-Lucé (Cloux) near Amboise. After settling in Clos-Lucé, Leonardo’s artistic output came to a virtual standstill. He drew up plans for the canal and gardens at the palace of Romorantin and for the construction of a palace near Amboise; he was also credited with having had a major hand in the plans for the Château of Chambord. Much of Leonardo’s time in France seemed to have been devoted to scientific studies and writings in his notebooks.

Leonardo was an avid and highly skilled draughtsman, and the large quantity of his surviving drawings (approximately 4,000 sheets) and notebooks far outweigh his finished paintings and sculptures. These drawings reveal the breadth of Leonardo’s intellect, his innovative mind, and his artistic process. In addition to many technical drawings for machines; anatomical, zoological, and botanical studies; sketches; and figural studies, Leonardo also made architectural drawings of centrally planned churches, many of them contemporary with Donato Bramante’s remodeling of S Maria delle Grazie and Leonardo’s execution of the Last Supper at the same complex. The notebooks also include fragments of a planned treatise on painting, which were compiled by Leonardo’s student Francesco Melzi after his death (Codex Urbinas) and first printed in 1651. Leonardo’s practice of writing backwards has been proposed as either motivated by secrecy or, perhaps more plausibly, a practical solution to the difficulty of writing left-handed.

Leonardo da Vinci’s genius extended across many fields: painting, sculpture, architecture, and various complex scientific research disciplines, including not only anatomy and physics but also highly specialised areas such as military technology and civil engineering. One might have expected that such a technically oriented mind would have been reflected in an artistic style that was precise, not to say meticulous. In effect, quite the contrary is true. Leonardo preferred to render the subtleties and vagaries of light and shade and the mysterious sfumato that is the basis of his style. He strove to create the effect of light not in terms of colour but rather as form so there is no sharp contrast between light and shade but, instead, a long and sustained transition from light towards shade. His figures are bathed in an ‘atmosphere’ that has a presence of its own; they emerge and merge back into the whole without sacrificing the constructive value of their form. In addition to his rendering of spontaneous movement and his ability to capture the serenity of facial expression, Leonardo achieves monumentality by often eliminating detailed settings. Leonardo’s commitment to naturalism in his painting goes hand in hand with his intense scientific study of all aspects of the natural world. Although he is considered the first of the ‘high’ Renaissance artists, in his scientific approach to painting he is quite distinct from his contemporaries, whose naturalism was so often tied to antique precedents.

Group Exhibitions

1979, From Leonardo to Titian: Italian Renaissance Paintings from the Hermitage, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Knoedler Gallery, New York

2001, Virtue and Beauty: Leonardo’s Ginevra de’ Benci and Renaissance Portraits of Women, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

2004, Painters of Reality: The Legacy of Leonardo and Caravaggio in Lombardy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Solo Exhibitions

1989, Leonardo da Vinci, Hayward Gallery, London

1989, Leonardo da Vinci: Studies of Drapery, Louvre, Paris

1996–1997, Leonardo’s Codex Leicester: A Masterpiece of Science, American Museum of Natural History, New York

1997, Leonardo da Vinci: Scientist, Inventor, Artist, Institut für Kulturaustausch, Tübingen, Museum of Science, Boston

2000, Leonardo da Vinci: The Codex Leicester, Notebook of a Genius, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

2002, Leonardo da Vinci: Inventor (Léonard de Vinci: l’inventeur), Pierre Gianadda Foundation, Martigny, Switzerland

2003, Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

2003, Leonardo da Vinci: Drawings and Notebooks (Léonard de Vinci. Dessins et Manuscrits) Louvre, Paris

2006, The Treatise on Painting: Manuscripts and Editions between the 16th and 19th Century, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

2006–2007, Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment, and Design, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

2007, The Mind of Leonardo: The Universal Genius at Work, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

2011, Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, National Gallery, London

Museum and Gallery Holdings

Cambridge (Fitzwilliam Mus.): A Rider on a Rearing Horse (c. 1481, metalpoint reinforced with pen and brown ink/pinkish prepared surface)

Edinburgh (Nat. Gal. of Scotland): Studies of Paws of a Dog or Wolf (c. 1400-1495, silverpoint drawing)

Florence (Gal. dell’Accademia): Vitruvian Man(c. 1487, pen and ink with metalpoint on paper)

Florence (Uffizi): Adoration of the Magi (c. 1480, oil/wood); Annunciation (1470s, oil/wood)

Krakow (Czartoryski Mus.): Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (or Lady with an Ermine)

London (British Library): Arundel Codex

London (NG): Virgin of the Rocks (or Virgin with the Infant Saint John Adoring the Infant Christ Accompanied by an Angel) (c. 1491-1508, oil/wood);Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist (c. 1499-1500, black and white chalk/brownish paper/canvas)

London (Victoria and Albert Mus): Forster Codex

Madrid (Biblioteca Nacional): two codices

Milan (Ambrosiana): Portrait of a Musician (c. 1485, oil/wood); Codex Atlantico

Milan (Biblioteca Trivulziano): Trivulziano Codex

Milan (S Maria delle Grazie): Last Supper

Holy Family

Munich (Alte Pinakothek): Madonna with the Carnation (1470s, oil/wood)

New York (Metropolitan MA): several drawings

Oxford (Christ Church College): seven drawings

Paris (Institut de France): Codices A through M; Ashburnham Codex

Paris (Louvre): La Gioconda (or Mona Lisa);St John the Baptist;Virgin and Child with St Anne; Virgin of the Rocks; La Belle Ferronnière (Lucrezia Crivelli?); Virgin Offering a Bowl of Fruit to the Infant Jesus (drawing); Isabella d’Este(drawing)

Parma (NG): Female Head

St Petersburg (Hermitage): Virgin and Child (Litta Madonna); Benois Madonna

Turin (Royal Library): Study for the Angel for ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’ (drawing)

Vatican (Pinacoteca Vaticana): St Jerome(1480s, tempera and oil/wood); Urbanis Codex

Washington, DC (NGA): Ginevra de’ Benci (c. 1474-1478, oil/panel, two-sided portrait)

Windsor (Windsor Castle, Royal Collection): Study for St James the Elder; notebooks

Auction Records

Paris, 1742: St Jerome, FRF 1,900

London, 1773: Christ and the Virgin with St Joseph, FRF 7,075

London, 1801: Laughing Infant, FRF 34,120

London, 1811: Female Portrait, FRF 78,700

Paris, June 1825: Leda and the Twins Castor and Helen, Pollux and Clytemnestra, FRF 175,000

Paris, 1850: La Colombine (Mistress of Francis I), FRF 81,200; Various Saints: Study for ‘The Last Supper’ (red and black chalk) FRF 16,600

Paris, 1865: Virgin Stooping towards Her Son, FRF 83,500

Paris, 1875: Initial Study for ‘The Adoration of the Magi’ (pen drawing) FRF 12,900; Study for ‘st Anne’ (black chalk, Indian ink, and wash) FRF 13,000

London, 1881: Virgin of the Rocks, FRF 225,000

London, 1888: Virgin in Low Relief, FRF 63,000

Paris, 1900: Draperies (study), FRF 12,500

Paris, 26-27 May 1919: Head of Old Man (silverpoint drawing heightened with white) FRF 6,000

London, 22 May 1925: Infant Jesus and Saint with a Lamb, GBP 1,890

London, 29 June 1926: Hermina: Emblem of Purety (pen) GBP 800; Study Folio (pen) GBP 760

London, 15 July 1927: Virgin with Flowers, GBP 2,100; Head of Leda, GBP 1,785

Paris, 25 Feb 1929: Profile Study of Old Man (pen) FRF 15,400

London, 10-14 July 1936: Wild Horse (pen) GBP 4,305

London, 23 May 1951: Head of the Virgin (charcoal, heightened with colour, study for the painting in the Louvre of The Virgin and St Anne) GBP 8,000

London, 26 March 1963: Head of an Old Man (caricature) (ink drawing with bistre wash) GNS 44,000

London, 21 May 1963: Virgin and Child with a Dog (pen drawing and wash) GBP 19,000

Paris, 12 June 1973: Horse (patinated bronze) FRF 160,000

New York, 17 Nov 1986: Three Child Studies and (recto) Three Lines of Text; Studies: Child, Head of Old Man, and Machine with (verso) Several Lines of Text (black chalk, pen, and brown ink, 8 × 5½ ins/20.3 × 13.8 cm) USD 3,300,000

Monaco, 1 Dec 1989: Draperies with Kneeling Figure Facing Left (brush and brown-grey wash, heightened with white gouache, 11¼ × 7¼ ins/28.8 × 18.1 cm) FRF 35,520,000; Draperies: Study with Figure Standing and Facing Right(brush and brown-grey wash, heightened with white gouache on canvas prepared with grey gouache, 11 × 7¼ ins/28.2 × 18.1 cm) FRF 31,080,000

London, 10 July 2001: Horse and Rider (silverpoint, 5 × 3 ins/12 × 8 cm) GBP 7,400,000

Bibliography

Bode, Wilhem von: Studien über Leonardo da Vinci, G. Grote, Berlin, 1921.

Sirén, Osvald: Leonardo da Vinci, G. Van Oest, Paris, 1928.

Suida, Wilhem: Leonardo und sein Kreis, F. Bruckmann, Munich, 1929.

Verga, Ettore: Bibliografia Vinciana 1493-1930, Zanichelli, Bologna, 1930.

Richter, Jean Paul: The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, Oxford University Press, London and New York, 1939.

Goldschieder, Ludwig: Leonardo da Vinci, Phaidon, London: Oxford University Press, New York, 1943.

Popham, Arthur Ewart: The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, Reynal and Hitchcock, New York, 1945 (2nd ed., Jonathan Cape, London, 1946).

Heydenreich, Heinrich Ludwig: Leonardo da Vinci, 2 vols., Holbein-Verlag, Basel, 1954.

Freud, Sigmund: Leonardo da Vinci: A Memory of His Childhood, Routledge, London, 1957 (reprinted2006).

Chastel, André (ed.)/Callmann, Ellen (trans.): The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci: Leonardo da Vinci on Art and the Artist, Orion Press, New York, 1961.

Huard, Pierre/Grmek, Mirko Dražen: Léonard de Vinci. Dessins scientifiques et techniques, R. Dacosta, Paris, 1962.

Pedretti, Carlo: A Chronology of Leonardo da Vinci’s Architectural Studies after 1500, E. Droz, Geneva,1962.

Gombrich, Ernst Hans: ‘Leonardo’s Methods of Working Out Compositions’, in Norm and Form: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance, Phaidon, London, 1966.

Clark, Kenneth: The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Phaidon, London, 1968–1969.

Panofsky, Erwin: The Codex Huygens and Leonardo da Vinci’s Art Theory, Greenwood, Westport (CT),1971.

Pedretti, Carlo: Leonardo da Vinci: A Study in Chronology and Style, Thames and Hudson, London, 1973.

Kemp, Martin: Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man, Dent, London, 1981 (2nd rev. ed. 1988).

Calvi, Gerolamo: I Manoscritti di Leonardo da Vinci: dal punto di vista cronologica, storico e biografico,Bramante Editrice, Busto Arsizio, 1982.

Clark, Kenneth/Kemp, Martin: Leonardo da Vinci: An Account of His Development as an Artist,Harmondsworth, Middlesex; Viking, New York, 1988 (new rev. ed.).

Batkin, Leonid M.: Leonardo da Vinci, Laterza, Rome, 1988.

Viatte, Françoisee/Pedretti, Carlo/Chastel, André: Leonardo da Vinci: les études de draperies, exhibition catalogue, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 1989.

Maiorino, Giancarlo: Leonardo da Vinci: The Daedalian Mythmaker, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, 1992.

Turner, Richard: Inventing Leonardo, Alfred A. Kopf, New York, 1993.

Frère, Jean Claude: Léonard de Vinci, Du Terrail, Paris, 1994.

Cole Ahl, Diane (ed.): Leonardo da Vinci’s Sforza Monument Horse: The Art and the Engineering, Lehigh University Press, Bethlehem (PA), Associated University Presses, Cranbury (NJ) and London, 1995.

Letze, Otto/Buchsteiner, Thomas/Guttmann, Nathalie: Leonardo da Vinci: Scientist, Inventor, Artist, exhibition catalogue, Institut für Kulturaustausch, Tübingen; G. Hatje, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1997.

Arasse, Daniel: Leonardo da Vinci: The Rhythm of the World, Konecky and Konecky, New York, 1998(French ed., Hazan, Paris, 1997).

Zöllner, Frank: La ‘Battaglia di Anghiari’ di Leonardo da Vinci fra mitologia e politica, Giunti, Florence,1998.

Zwijnenberg, Ribert: The Writings and Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci: Order and Chaos in Early Modern Thought, Cambridge University Press, New York, 1999.

Chastel, André: Leonardo da Vinci. Studi e ricerche 1952-1990, Phaidon, London, 1999.

Villata, Edoardo/Marani, Pietro C.: Leonardo da Vinci: i documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee,Castallo Sforzesco, Milan, 1999.

Farago, Claire: Leonardo da Vinci: Selected Scholarship, 5 vols, Garland, New York, 1999.

Brown, David Alan: Leonardo da Vinci: Origins of a Genius, Yale University Press, New Haven (CT), 1998.

Desmond, Michael/Pedretti, Carlo: Leonardo da Vinci: The Codex Leicester, Notebook of a Genius, exhibition catalogue, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney; Powerhouse Publishing, Haymarket (Australia),2000.

Nuland, Sherwin: Leonardo da Vinci, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 2000.

Léonard de Vinci: l’inventeur, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny, 2002.

Goffen, Rona: Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian, Yale University Press, New Haven (CT), 2002.

Bambach, Carmen C. (ed.), and others: Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman, exhibition catalogue,Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2003.

Zöllner, Frank/Nathan, Johannes: Leonardo da Vinci, 1452–1519: The Complete Paintings and Drawings, catalogue raisonné, Taschen, Cologne and London, 2003.

Kemp, Martin: Leonardo, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004.

Kemp, Martin: Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment and Design, exhibition catalogue, Princeton University Press, Princeton (NJ), 2006.

Bernardoni, Andrea: Leonardo e il monumento equestre a Francesco Sforza: Storia di un’opera mai realizzata, Giunti, Florence, 2007.

Farago, Claire (ed.): Re-reading Leonardo: The Treatise on Painting across Europe, 1550–1900, Ashgate, Burlington (VT) and Farnham (England), 2009.

Syson, Luke, and others: Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, exhibition catalogue, National Gallery, London, 2011.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Leonardo da Vinci from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists appeared first on OUPblog.

![Bill Burke and Jane Mull, members of the Committee of the American Council of Learned Societies on the Protection of Cultural Treasures in War Areas, working with Gladys Hamlin, draftswoman, at the Frick Art Reference Library on a map of Paris. circa 1943-44. The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Photographs. [National Archives photograph]](http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Frick-Library.jpg)