By Kandice Rawlings

Leonardo da Vinci was born 562 years ago today, and we’re still fascinated with his life and work. It’s no real mystery why – he was an extraordinary person, a genius and a celebrity in his own lifetime. He left behind some remarkable artifacts in the form of paintings and writings and drawings on all manner of subjects. But there’s much about Leonardo we don’t know, making him susceptible to a number myths, theories, and entertaining but inaccurate representations in popular culture. The following are some of my favorites.

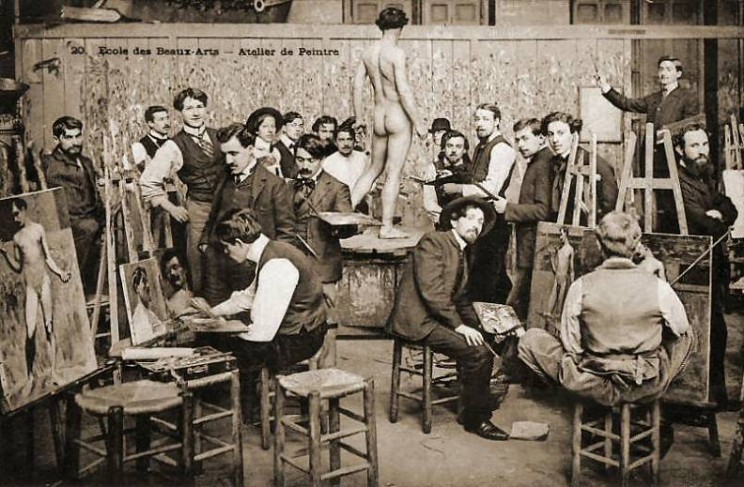

Leonardo da Vinci, Presumed Self Portrait, circa 1512. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #1 – Leonardo was gay.

Leonardo’s possible homosexuality is one of the more prevalent – and more plausible – myths circulating about the artist, and has the backing of none other than Sigmund Freud. There’s no way of knowing Leonardo’s sexual orientation for sure, but he isn’t known to have had romantic relationships with any women, never married, and in 1476 was accused (but later cleared) of charges of sodomy – then a capital crime in Florence. Scholars’ opinions on the issue fall along a spectrum between “maybe” and “very probably”.

Conclusion: Maybe true.

Myth #2 – Leonardo wrote backward to keep his ideas secret, and his notebooks weren’t “decoded” until long after his death.

For all his skill, Leonardo was not a prolific painter – the major part of his surviving output is in the form of his notebooks filled with theoretical and scientific writings, notes, and drawings. His strange habit of writing backward in these notebooks has been used to perpetuate the image of the artist as a mysterious, secretive person. But in fact it’s much more likely that Leonardo wrote this way simply because he was left-handed, and found it easier to write across the page from right to left and in reverse. No decoding is necessary – just a mirror. Leonardo’s theoretical writings and other notes were preserved by his follower and heir Francesco Melzi, and were widely known, at least in artistic circles, during the 16th and 17th centuries. Published extracts began appearing in 1651.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #3 – Leonardo put “secret” codes and symbols in his works.

I’d rather not get into all the problems with The Da Vinci Code too much, but I have to credit this 2003 book, by renowned author Dan Brown, for a lot of these theories. Aside from the fact that the book is full of factual errors (example: Leonardo’s “hundreds of Vatican commissions,” which actually number in the vicinity of zero) and twists the historical record, its readings of Leonardo’s artworks are based on some fundamentally flawed conceptions about the making, meaning, and purpose of art in the Italian Renaissance. In Leonardo’s world, paintings like the Last Supper in Milan were made according to patrons’ requirements, with very specific Christian meanings to be conveyed. Despite Leonardo’s artistic innovations, the content of his religious paintings and portrayal of religious figures (with the exception of some details in an altarpiece from the 1480s) were not untraditional.

Conclusion: False.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa, between 1503-1505. Louvre. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #4 – The Mona Lisa is a self-portrait/male lover in disguise/woman with high cholesterol.

Martin Kemp has observed, “The silly season for the Mona Lisa never closes.” The ridiculous theories about this painting abound. Here’s what we can say with reasonable certainty: Leonardo started the painting, probably a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, a merchant’s wife, while in Florence around 1503. For unknown reasons, he didn’t deliver it to the patron, however, and it ended up in the possession of his workshop assistant Salai (who some think was Leonardo’s lover – again, without evidence). There’s no reason to think that Leonardo recorded in this painting his own features or those of Salai, even if, as many art historians believe, he continued to work on the painting after he left Florence for Milan and then France. In a theory that deviates from the usual speculation about the identity of the sitter, an Italian scientist thinks that the way Leonardo portrayed the sitter shows she had high cholesterol. Right, because Renaissance paintings are straightforward, scientific images, pretty much just like MRIs and X-rays.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #5 – Leonardo made the image of Christ on the Shroud of Turin.

The Shroud of Turin is a relic purported to be the shroud that Christ’s body was buried in after the Crucifixion. According to its legend, the image of his body was miraculously transferred to the cloth when he was resurrected. The idea that Leonardo forged it depends on claims that the proportions of Christ’s face as depicted on the shroud match those in a drawing that is thought to be a self-portrait by the artist, and that Leonardo devised a photographic process that transferred the image of his face to the shroud. The fact that the shroud dates to at least the mid-14th century, a hundred years before Leonardo’s birth, just makes this already kooky theory even harder to buy. I’ll admit, though, that I haven’t read the whole book explaining it … and I’m not going to.

Conclusion: False.

Myth #6 – Leonardo was a vegetarian.

Vegetarianism would have been pretty unthinkable in Renaissance Italy (and veganism just plain absurd); people probably ate about as much meat as they could afford. The most commonly cited quote used to back up this claim is taken from a novel (see p. 227) and often misattributed to Leonardo himself. None of Leonardo’s own writings or early biographies mentions any unconventional eating habits. There’s really only one documentary source that might be relevant, a letter written by a possible acquaintance of the artist, who compares Leonardo to people in India who don’t eat meat or allow others to harm living things. Pretty tenuous, but vegetarians love to claim him.

Conclusion: Probably false.

Myth #7 – Leonardo invented bicycles, helicopters, submarines, and parachutes.

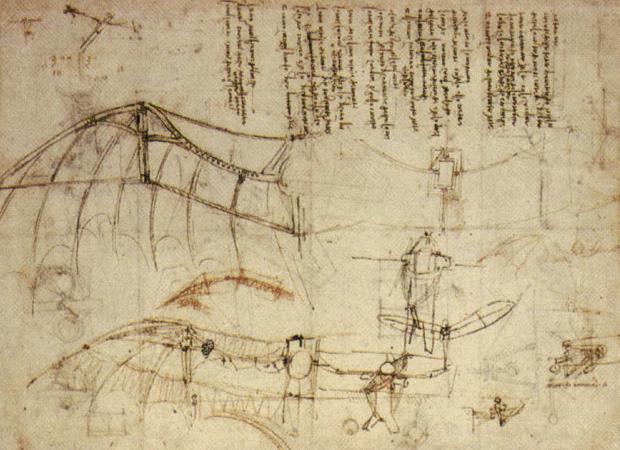

It’s true that Leonardo was fascinated with mechanics, aerodynamics, hydrodynamics, flight, and military engineering, which he touted in his famous letter to Ludovico Sforza seeking a position at the court of Milan. Leonardo’s notebooks contain many designs for machines and devices related to these explorations. But these were, for the most part, probably not ideas that Leonardo considered thoroughly enough to actually build and demonstrate. In the case of the bicycle, the drawing was likely made by someone else, and might even be a modern forgery.

Conclusion: Not so much.

Leonardo da Vinci, Design for a Flying Machine, 1488. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Myth #8 – Leonardo built robots.

While it sounds nutty, this one’s not so far off the mark, if you consider automatons – mechanical devices that seem to move on their own – to be robots. In a plot line of the cable fantasy drama Da Vinci’s Demons, Leonardo constructs a flying mechanical bird to dazzle the crowds gathered in the Cathedral piazza for Easter. A reliable historical record instead points to a lion that Leonardo made for the King of France’s triumphal entry into Milan in 1509. One observer’s description reads:

When the King entered Milan, besides the other entertainments, Lionardo da Vinci, the famous painter and our Florentine, devised the following intervention: he represented a lion above the gate, which, lying down, got onto its feet when the King came in, and with its paw opened up its chest and pulled out blue balls full of gold lilies, which he threw and strewed about on the ground. Afterwards he pulled out his heart and, pressing it, more gold lilies came out … Stopping beside this spectacle, [the King] liked it and took much pleasure in it.

Wow.

Conclusion: True.

If you’re interested in learning more about Leonardo, including the current locations of his works, read his biography from the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, or, for a longer treatment, pick up the accessible but smart book by leading expert Martin Kemp.

Kandice Rawlings is Associate Editor of Oxford Art Online and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists. She holds a PhD in art history from Rutgers University.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Leonardo da Vinci myths, explained appeared first on OUPblog.