|

| Students with Bibles |

|

| Students with Bibles |

Are Christians persecuted in America? For most of us this seems like a preposterous question; a question that could only be asked by someone ginning up anger with ulterior motives. No doubt some leaders do intentionally foster this persecution narrative for their own purposes, and it’s easy to dismiss the rhetoric as hyperbole or demagoguery, yet there are conservative Christians all across the country who genuinely believe they experience such persecution.

The post Persecuted Christians in America appeared first on OUPblog.

In May 2014, in Sudan, Meriam Ibrahim was sentenced to death for the ‘crime’ of ridda (apostacy) and to 100 lashes for the ‘offence’ of zena (sexual immorality). The case generated international outrage among those who care about women’s rights and religious freedom.

The post Remembering women sentenced to death on International Women’s Day appeared first on OUPblog.

On 1 July 2014, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) announced its latest judgment affirming France’s ban on full-face veil (burqa law) in public (SAS v. France). Almost a decade after the 2005 controversial decision by the Grand Chamber to uphold Turkey’s headscarf ban in Universities (Leyla Sahin v. Turkey), the ECHR made it clear that Muslim women’s individual rights of religious freedom (Article 9) will not be protected. Although the Court’s main arguments were not the same in each case, both judgments are equally questionable from the point of view of protecting religious freedom and of the exclusion of Muslim women from public space.

The recent judgment was brought to the ECHR by an unnamed French woman known only as “SAS” against the law introduced in 2011 that makes it illegal for anyone to cover their face in a public place. Although the legislation includes hoods, face-masks, and helmets, it is understood to be the first legislation against the full-face veil in Europe. A similar ban was also passed in Belgium after the French law. France was also the first country to ban the wearing of “conspicuous religious symbols” – directed at the wearing of the headscarf in public high schools — in 2004. Since then several European countries have established policies restricting Muslim religious dress.

The French law targeted all public places, defined as anywhere not the home. Penalties for violating the law include fines and citizenship lessons designed to remind the offender of the “republican values of tolerance and respect for human dignity, and to raise awareness of her penal and civil responsibility and duties imposed life in society.”

SAS argued the ban on the full-face veil violated several articles of the European Convention and was “inhumane and degrading, against the right of respect for family and private life, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of speech and discriminatory.” She did not challenge the requirement to remove scarves, veils and turbans for security checks, also upheld by the ECHR. The ECHR rejected her argument and accepted the main argument made by the government: that the state has a legitimate interest in promoting a certain idea of “living together.”

By now, it is clear that Article 9 of the European Convention does not protect freedom of religion when the subject is a woman and the religion is Islam. While this may seem harsh, consider the ECHR’s 2011 judgment in Lautsi v. Italy, which found the display of the crucifix in Italian state schools compatible with secularism.

In Lautsi case, the Court argued that the symbol did not significantly impact the denominational neutrality of Italian schools because the crucifix is part of Italian culture. Human rights scholars have not missed the contrast between the Italian case and the earlier 2005 decision in Leyla Sahin v Turkey where the Court found that the wearing of the headscarf by students was not compatible with the principle of laicité or secularism.

The Court did not make a value judgment in SAS case about Islam, women’ rights in Islamic societies, or gender equality, as it did in earlier cases where they upheld bans on the wearing of the headscarf by teachers and students in France, Turkey and Switzerland. In all cases involving Islamic dress codes, the ECHR emphasized the “margin of appreciation” rule, which permits the court to defer to national laws.

The ECHR acted politically and opportunistically not to challenge France’s strong Republicanism and principles of laicité, sacrificing the rights of the small minority of Muslims who wear the full-face veil. Rather than protecting the individual freedom of the 2000 women, the ECHR protected the majority view of France.

The ECHR is the most powerful supra national human rights court and its decisions have widespread impact. Several countries in Europe, such as Denmark, Norway, Spain, Austria, and even the UK, have already started to discuss whether to create similar laws banning the burqa in public places. This raises concerns that cases related to the cultural behavior and religious practices of minorities could shift public opinion dangerously away from the principles of multiculturalism, democracy, human rights and religious tolerance.

The most recent law bans the full-face veil, but tomorrow, the prohibitions may be against halal food, circumcision, the location of a mosque or the visibility of a minaret; even religious education might be banned for reasons of public health, security or cultural integration. Muslims, Roma, and to some extent Jews and Sikhs, are already struggling to be accepted as equal citizens in Europe, where right wing extremism is rising, in a situation of economic crisis.

The ECHR should be extremely careful in its decisions, given the growth of nationalism, xenophobia, and anti-immigrant sentiment in Europe.Considering this context, the EHCR’s main argument in this latest judgment is worrisome, since it accepted France’s view that covering the face in public runs counter to the society’s notion of “living together,” even though this is not one of the principles of the European Convention.

The Court recognized that the concept of “living together” was problematic (Para 122). And, even in using the “wide margin of appreciation” rule, the Court acknowledged that it should “engage in a careful examination” to avoid majority’s subordination of minorities. Considering the Court’s own rules, the main reasoning for the full face veil ban—“living together” seems to be inconsistent with the Court’s own jurisprudence.

Further concerns were raised about Islamophobic remarks during the adoption debate of the French Burqa Law, and evidence that prejudice and intolerance against Muslims in French society influenced the adoption of the law. Such concerns were more strongly raised by the two dissenting opinions. The dissent found the Court’s insensitivity to what’s needed to ensure tolerance between the vast majority and a small minority could increase tensions (Para 14). The dissenting opinion was especially critical of prioritizing “living together,” not even a Convention principle, over “concrete individual rights” guaranteed by the Convention.

While the integration of Muslims and other immigrants across Europe is a legitimate concern, it is vitally important the ECHR’s constructive role. The decision in SAS v France is a dangerous jurisprudential opening for future cases involving the religious and cultural practices of minorities. The French burqa law has created discomfort among Muslims. By upholding the law, the European court deepens the mistrust between the majority of citizens and religious minorities.

Headline image credit: Arabic woman in Muslim religious dress, © Vadmary, via iStock Photo..

The post The French burqa ban appeared first on OUPblog.

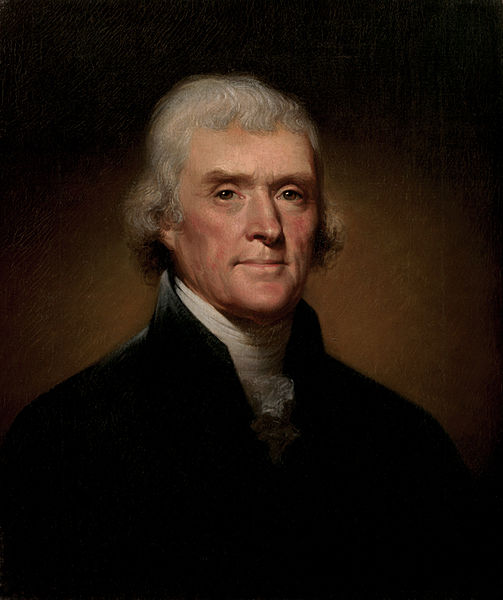

Surprisingly, in a country that cares about its founding history, few Americans know of Thomas Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom, a document that Harvard’s distinguished (emeritus) history professor, Bernard Bailyn called, “the most important document in American history, bar none.”

Yet that document is not found in most school standards, so it’s rarely taught. How come? Maybe because it is a Virginia document, passed by Virginia’s General Assembly. Or maybe because its ideas found their way directly into the Constitution’s First Amendment and that seems enough for most Americans.

Why do Bailyn and some others think it so important? Because it was radical, trailblazing, and uniquely American: no government before had ever taken the astonishing stand that it takes. In essence it says that religious belief is a personal thing, a matter of heart and soul, and that government has no right to meddle with beliefs, or tax citizens to support churches they may disavow. That wasn’t the way governments were expected to operate.

Imagine you live in 18th century Virginia: According to a law on the books you have to go to church—every day–usually for both morning and evening prayer. If you don’t go you could be whipped, sentenced to work on an oceangoing galley, or worse. And you don’t have a choice of churches. In Virginia the established church is Anglican. That means you are assessed taxes to support that church whether you believed in it or not. You couldn’t be a member of the legislature unless you are a member of the Established Church. So the legislation of the House of Burgesses reflect the world of its Anglican delegates.

But the colonies are home to independent folk who braved a turbulent ocean to be able to think for themselves. Roger Williams, kicked out of Puritan Massachusetts, talks of “freedom of conscience” and lets anyone who wishes settle in the colony he founds on Rhode Island. The Long Island town of Flushing has a charter that promises settlers freedom of conscience, so leaders there petition New York Governor Peter Stuyvesant concerning the public torturing of Quaker preacher Robert Hodgson. In the Flushing Remonstrance they write, “We desire in this case not to judge lest we be judged.” In Virginia, Jemmy Madison stands outside the Orange County jail and listens as a Methodist preacher, behind bars, spreads the word of the Gospel. Why are Methodists, Baptists and Presbyterians being put in jail, Madison asks?

In 1777 Jefferson writes the eloquent Statute for Religious Freedom, introducing it into the legislature in 1779. This is a Revolutionary time and England’s church has to go. Will an established American church succeed it?

Patrick Henry, popular and powerful, introduces a bill that seems enlightened: it calls for public assessments to support all Christian worship. James Madison counters in his remarkable Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, arguing the case for full religious freedom. Most legislators are perplexed. Every nation has its state church. George Washington is on the fence. If citizens are not forced to go to church will they sink into immorality? What is the role of government?

John Locke has written a famous letter on religious tolerance, but Jefferson and Madison are clear: this statute is not about tolerance, it is about full acceptance — and jurisdiction. Jefferson’s point is that governments have no business telling people what they should believe. In his Notes on Virginia he says,

“The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or one god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg. […] To suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion. . .is a dangerous fallacy, which at once destroys all religious liberty.”

Meanwhile Patrick Henry’s bill passes its first two readings. A third and it becomes law. Jefferson writes to Madison from Paris where he is ambassador, “What we have to do is devotedly pray for his death.” (He’s talking about Henry.) Madison takes a pragmatic path. He gets Patrick Henry kicked upstairs into the governor’s chair, where he has no vote. Then he reintroduces Jefferson’s bill for establishing religious freedom. It finally passes, on 16 January 1786.

It turns out that Virginians are no more, nor less, moral than they were when they were forced to go to church. George Washington becomes one of the biggest fans of the idea of religious freedom. In a famous letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport Rhode Island, he says,

“The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy–a policy worthy of imitation. . .It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.”

Joy Hakim, a former teacher, editor, and writer won the prestigious James Michener Prize for her series, A History of US, which has sold over 5 million copies nationwide. From Colonies to Country, one of the volumes in that series, includes the full text of Jefferson’s statute. Hakim is also the author of The Story of Science, published by Smithsonian Books. A graduate of Smith College and Goucher College she has been an Associate Editor at Norfolk’s Virginian-Pilot, and was Assistant Editor at McGraw-Hill’s World News.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Official Presidential portrait of Thomas Jefferson. 1800. By the White House Historical Association. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Thomas Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom appeared first on OUPblog.

“In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are under-written, the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc.

Having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our King and Country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine our selves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the eleventh of November in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Dom. 1620.”

When the Mayflower—packed with 102 English men, women, and children—set out from Plymouth, England, on 6 September 1610, little did these Pilgrims know that sixty-five days later they would find themselves not only some 3,000 miles from their planned point of disembarkation but also pressed to pen the above words as the governing document for their fledgling settlement, Plimouth Plantation. Signed by 41 of the 50 adult males, the “Mayflower Compact” represented the type of covenant this particular strain of puritans believed could change the world.

While they hoped to achieve success in the future, these signers were especially concerned with survival in the present. The lives of these Pilgrims for the two decades or so prior to the launching of the Mayflower had been characterized by Separatism. Their decision to separate from the Church of England as a way to protest and to purify what they saw as its shortcomings had led to the necessity of illegally emigrating from the country of England and seeking refuge in the Netherlands. A further separation was needed as these English families realized that the Netherlands offered neither the cultural nor economic opportunities they really desired. But returning to England was out of the question. Thus, in order to discover the religious freedom they desired, these Pilgrims needed to remove yet again, which became possible because of an agreement made with an English joint-stock company willing to pair “saints” and “strangers” in a colony in the American hemisphere.

Despite the fact that they were the ones who had recently arrived in North America, the Pilgrims taxed the abilities of both the land and its native peoples to sustain the newly arrived English. Such taxation became most visible at moments of violent conflict between colonists and Native Americans, as in 1623 when Pilgrims massacred a group of Indians living at Wessagussett. Following the attack, John Robinson, a Pilgrim pastor still in the Netherlands, wrote a letter to William Bradford, Plimouth’s governor, expressing his fears with the following words: “It is also a thing more glorious, in men’s eyes, than pleasing in God’s or convenient to Christians, to be a terrour to poor barbarous people. And indeed I am afraid lest, by these occasions, others should be drawn to affect a kind of ruffling course in the world.” As his letter makes clear, Robinson clearly hoped the colonists would offer the indigenous peoples of New England the prospect of redemption–spiritually and culturally–rather than the edge of a sword. The Wessagussett affair, however, illustrated such redemption had not been realized. From at least that moment on, relationships between English colonists and the indigenous peoples of North America more often than not followed ruffling courses.

While an established state church isn’t a main threat nearly 400 years later, some of the Pilgrims’ concerns still haunt many Americans. Like those English colonists preparing to set foot on North American soil, we remain afraid of those we perceive as different than us–culturally, racially, ethnically, and the like. But the tables are turned. We are now the ones striving to protect ourselves from a stream of illegal and “undocumented” immigrants attempting to pursue their dreams in a new land. Our primary method of protection? Separatism. Like the Pilgrims we often remain unwilling to welcome those we define as different. We’ll look to them for assistance when necessary, rely on their labor when convenient, take advantage of their needs when possible, but we won’t welcome them as neighbors and equals in any real sense nor do we seek to provide reconciliation and redemption to people eager to embrace the potential future they see among us.

Ruffled courses persist as the United States wrestles with how it ought to treat those men, women, and children who, like the Pilgrims of the seventeenth century, are looking for newfound opportunities. As we remember the voyage of the seventeenth-century immigrants who departed England on 6 September 1610 and recall their many successful efforts to establish a lasting settlement in a distant land, we do well to celebrate not only their need to separate but also their dedication to “covenant and combine [them]selves together into a civil body politic.” The world has enough ruffling courses and perhaps needs the purifying reform modeled by the Pilgrims and the potential redemption those like John Robinson hoped for as they agreed to work together for the common good. In short, one would hope that a people whose history was migration from another land would be more welcoming than we often are, especially in our dealings with the immigrants and the impending immigration reform of our own day.

Richard A. Bailey is Associate Professor of History at Canisius College. He is the author of Race and Redemption in Puritan New England. His current research focuses on western Massachusetts as an intersection of empires in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, fly fishing in colonial America, and the concept of friendship in the life and writings of Wendell Berry. You can find Richard on Twitter @richardabailey

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Mayflower Compact, 1620. Artist unknown, from Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Undocumented immigrants in 17th century America appeared first on OUPblog.

Tweet

In this two-part series, Michelle and Lauren explore some of the most hot-button issues in religion this past year.

Subscribe and review this podcast on iTunes!

Featured in Part 1:

Christopher Hitchens and Tariq Ramadan Debate: Is Islam a Religion a Peace?

Highlights and exclusive interviews with Hitchens, Ramadan, & New York Times National Religion Correspondent Laurie Goodstein

Read more and watch a video courtesy of the 92nd St Y HERE.

Read more and watch a video courtesy of the 92nd St Y HERE.

* * * * *

Nick Mafi, Oxford University Press employee extraordinaire

* * * * *

David Sehat, author of The Myth of American Religious Freedom

* * * * *

Like Gettysburg, the National Mall, and other historic sites, Ground Zero is a place whose symbolic importance extends well beyond local zoning disputes and real estate deals. The recent controversy over a proposal to build a Muslim community center two blocks away from the former World Trade Center shows it clearly: the geography of Lower Manhattan has become a sacred ground on which religious and political battles of national importance are being waged.

After New York’s Landmarks Preservation Commission gave its approval for the demolition of the building now located on 45-47 Park Place in Lower Manhattan, the Rev. Pat Robertson’s American Center for Law and Justice announced that it is suing to stop the project.

Though Robertson’s organization is supposedly dedicated to the “ideal that religious freedom and freedom of speech are inalienable, God-given rights,” it is not primarily concerned with religious rights, at least not the rights of Muslims. It is instead part of a loose coalition of Americans who have identified the presence of Muslims, both at home and abroad, as a primary threat to both the United States and the Judeo-Christian heritage.

Their Muslim-bashing has deep roots in American history. Since the days of Cotton Mather, the New England Puritan minister, many Americans have associated Muslims with religious heresy. In the early 1800s, as the United States waged its first foreign war against the North African Barbary states, politicians, ministers, and authors regularly used themes of oriental despotism, harems, and Islamic violence in political campaigns, novels, and sermons.

Later, when the U.S. failed to quell Muslim revolts during the U.S. occupation of the Philippines in the early twentieth century, U.S. Army Gen. Leonard Wood called for the extermination of all Filipino Muslims since, according to him, they were irretrievably fanatical.

Islamophobia, an odd combination of racism, xenophobia, and religious bias, receded in importance during the 1900s as the specter of communism replaced it as a primary symbol of foreign danger. But with the fall of the Soviet Union, stereotypes about the Islamic “green menace” have once again become a central aspect of our culture.

This time Muslims are fighting back. Their civil rights and religious leaders are challenging this old American prejudice, in part through unprecedented interfaith community activism. Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, the leader of the group proposing the Muslim community center near Ground Zero, is one of them.

In response to questions about why he wants to build a community center so close to Ground Zero, Rauf has said that he wants the community center to be a source of healing, not division. Rauf also pledged that Park51, as the project is now called, will be a “home for all people who are yearning for understanding and healing, peace, collaboration, and interdependence.”

Rauf has powerful friends–or at least allies. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who choked up defending the right of Muslims to build the community center during a speech in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, argues that “we would be untrue to the best part of ourselves…if we said ‘no’ to a mosque in Lower Manhattan.”

Those who agree with Mayor Bloomberg represent the other major faction struggling for the American soul at Ground Zero. For them, the American soul is imperiled when its founding ideals are cast aside. In this case, the ideal is the first amendment guarantee of the free exercise of religion. “Of all our precious freedoms,” said Bloomberg,

As soon as I spotted the Social Justice Challenge button dotted all over the blogosphere, I knew that I would have to come up with some very good arguments not to take it on… so you will now find said button in our side-bar and here is my first post as an Activist for this month. If you haven’t already, I really do recommend you read this post, which explains the workings of the Challenge much better than I ever could… I will just say that this is a Challenge to do, as well as to absorb…

As soon as I spotted the Social Justice Challenge button dotted all over the blogosphere, I knew that I would have to come up with some very good arguments not to take it on… so you will now find said button in our side-bar and here is my first post as an Activist for this month. If you haven’t already, I really do recommend you read this post, which explains the workings of the Challenge much better than I ever could… I will just say that this is a Challenge to do, as well as to absorb…

Launching January’s theme of Religious Freedom, which happens to run parallel to our own current theme of Respect for Religious Diversity, we are asked to answer a few questions:

What is the first thing that comes to your mind when you think of religious freedom?

Peace and harmony – when we all learn to respect the right of each individual to follow (or not) the religion of their choice without fear of persecution, the human race will come close to achieving them. And education also comes to mind – because children (and adults) need to find out about the different world faiths, and learn to value both the diversity and shared values that they have at their heart.

What knowledge do you have of present threats to religious freedom in our world today?

I have some awareness of religious intolerance across the world – but I’m not going to go into it here…

Have you chosen a book or resource to read for this month?

With my sons, I’m going to read Many Windows: Six Kids, Five Faiths, One Community by Rukhsana Khan with Elisa Carbone and Uma Krishnaswami (Napoleon, 2008) and The Grand Mosque of Paris: A Story of How Muslims Rescued Jews During the Holocaust by Karen Gray Ruelle and Deborah Durland DeSaix (Holiday House, 2009), both of which I have already read… I haven’t chosen something new for myself yet… if I hadn’t recently read Wanting Mor (also by Rukhsana) , I would choose that…

Why does religious freedom matter to you?

It is a human right.

It’s been a while since I’ve posted an update on my book series, Kaimira. Book one (The Sky Village) is pretty much done except for the illustrations and the back matter. There will be six full-spread (2 page) illustrations, which is rare for a YA book and which I’m terribly excited about. Don’t tell the illustrator, but I’m using one of the illustrations as my computer desktop. The back matter consists of several fun index-type world building pieces, some with sketches.

As for book two, Nigel and I are about 50,000 words into it. We’ve left behind the two settings from book one (the Sky Village and the Demon Caves) and it’s huge fun building out the new settings and cultures.

I love me some world building.

In related news, I was trying to create a Warcraft III custom map / scenario that showed one of the Kaimira battles. There are several different types of golems, and they make excellent meks, and there are a number of different types of animals. (The world of Kaimira is set in a future in which humans, animals, and robots are at war with one another.)

In related news, I was trying to create a Warcraft III custom map / scenario that showed one of the Kaimira battles. There are several different types of golems, and they make excellent meks, and there are a number of different types of animals. (The world of Kaimira is set in a future in which humans, animals, and robots are at war with one another.)

Once I’m done, I’ll have a fun little Warcraft game in which the robots are occupying the city, the beasts are surrounding the city ready to invade, and the humans are in one little corner trying to survive in this 3-way battle, and then ultimately pushing back the robots and beasts and taking back the city.

Once I’m done, I’ll have a fun little Warcraft game in which the robots are occupying the city, the beasts are surrounding the city ready to invade, and the humans are in one little corner trying to survive in this 3-way battle, and then ultimately pushing back the robots and beasts and taking back the city.