By Anatoly Liberman

Unlike hogwash or, for example, flapdoodle, the noun balderdash is a word of “uncertain” (some authorities even say of “unknown”) origin. However, what is “known” about it is probably sufficient for questioning the disparaging epithets. We can dismiss with a condescending smile all kinds of imaginative rubbish (balderdash?) proposed by those who believed that knowing one or two old languages is enough for discovering an etymology, but one such guess is curious. According to it, the English noun goes back to Hebrew Bal, allegedly contracted from Babel, and dabar. The “curiosity” consists in the fact that there is a German verb (aus)baldowern “to nose out a secret or some information” (aus- is a prefix), from the language of the underworld. It goes back to Yiddish, ultimately Hebrew, ba’al-dabar “the lord of the word or of the thing” (ba’al has nothing to do with Babel). Thus, a fanciful etymology suggested for one word in English fits a German word of similar structure.

An equally ingenious attempt to supply balderdash with divine ancestry takes us all the way to the north. Engl. jovial, from French, from Italian, from Latin, was coined with the sense “under the influence of the planet Jupiter” (which astrologists regarded as the source of happiness”; compare by Jove!). The name of the most beautiful Scandinavian god was Baldr, Anglicized as Balder. Inspired by those facts, a resourceful author wrote in 1826: “The vilest of prose and poetry is called balder-dash; now Balder was among the Scandinavians the presiding god of poetry and eloquence.” Poor Baldr (who, incidentally, had nothing to do with poetry and eloquence)! As though it was not enough to be murdered at the Assembly with the mistletoe… He also had to bear the responsibility for enriching the English language with the word balderdash, which surfaced only at the end of the sixteenth century, millennia after the heinous deed.

As often in such cases, it remains unclear whether the word under discussion is native or borrowed. Not surprisingly, Spanish baldon(e)ar “to insult” and Welsh baldorddus “tattling” have been cited as possible etymons of balderdash. The trouble with Celtic words is that, even when the connection looks good, we cannot always ascertain the direction of borrowing (for example, from English to Welsh or from Welsh to English?). The history of English etymology is full of the Celtomaniacs who traced hundreds of words to Irish Gaelic, and of passionate deniers, who refused to believe that any Celtic language had the power to influence English. Besides, as one should never tire of repeating, it is not enough to point to a similar-sounding word in a foreign language without reconstructing the path of penetration. When and in what circumstances could a Spanish verb become so popular in England that English speakers adopted it as their slang (and a noun into the bargain)?

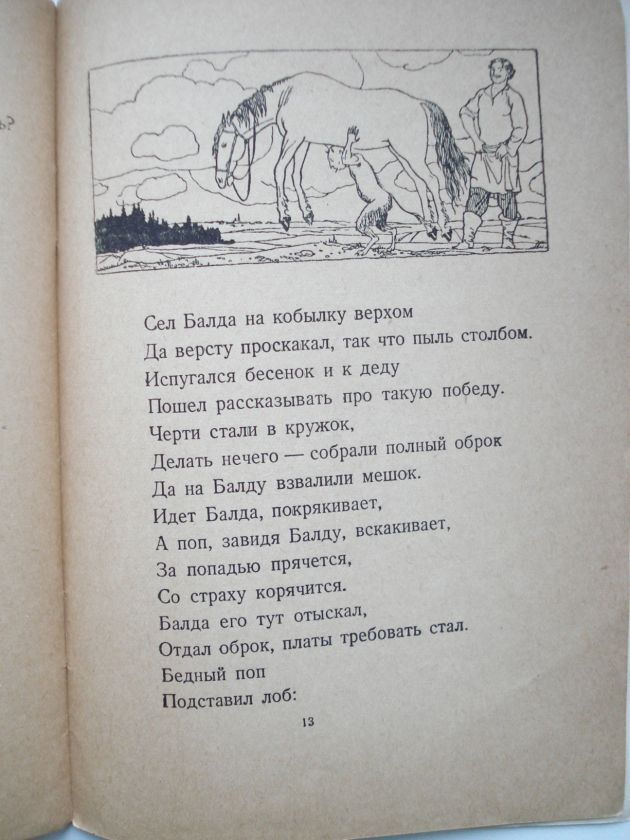

Pushkin’s Balda watching the old devil’s grandson who is trying to carry a mare after Balda easily “carried” it between his legs (that is, simply rode it).